2.1. Economic Perspectives

At a macro level, investment in education in Africa is characterised by several inconsistencies. While some countries make notable efforts to disburse a good proportion of their national revenues towards the education and health ministries, the majority of countries still allocate the lion’s share towards the security and defence ministries, even during times of peace. The situation is exacerbated by the fact that African economies within themselves are characterised by low income per capita, with widespread poverty and high inequality; Nigeria recently overtook India to become the poverty capital of the world [

11,

12,

13]. South Africa is one of the most unequal countries in the world [

14,

15], and there is sustained poverty in Malawi [

16,

17] and worsening living standards in Zimbabwe [

18]. These complex and gloomy macroeconomic dynamics filter down and affect educational institutions, making the attainment of SDGs a mammoth task. All these factors affect the both the quality of educational institutions and the quality of education itself.

Macroeconomic policy consistency creates the necessary stimuli for educational institutions to both develop internally and also partner with their respective institutions in other countries across the continent. As Mundell [

6,

7] postulated in his convergence argument, synchronised business cycles are a necessary prelude for sustainable integration and partnerships. Africa acknowledged this argument by establishing the “macroeconomic convergence criteria” through its regional economic communities (RECs). It was realised that there is a need to have fiscal and monetary policy discipline in order to achieve this synchronization, which will ultimately improve economic welfare [

19]. When nations are converging, it implies that their economies and/or institutions are moving in a systematic fashion, thereby attaining a similar level of wealth and development. Thus, convergence makes it easier for collaboration of micro-institutions such as universities or research centres in the respective countries. This argument possibly explains why there have been more university collaborations outside Africa compared to those within.

In North America, strong institutional commitment was signalled by Yale University, where there were various university-wide efforts on sustainability, guided by their strategic plan: the Sustainability Strategic Plan 2013–2016 [

20] (Yale University, 2015). In Sweden, the University of Uppsala Centre for Sustainable Development coordinated interdisciplinary initiatives on collaborations between the Centre and the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. Together, they aim to be research catalysts in education of sustainable development. In the case of developing countries, forty Brazilian universities representing 89% of offered programmes conducted exploratory research to map the emphasis given to the SDGs. The conclusion was that the involvement of SDGs in business administration programmes was slow and irregular, with only 13 (33%) of offered courses having some links to the subject [

21]. These irregular results could be attributable to a lack of macro convergence, which is characteristic of many developing economies.

However, ref. [

22] provides a contrary school of thought, anchored in ex-ante convergence. According to this idea, convergence is not a prelude to integration. On the contrary, it is the collaboration or partnerships of countries or institutions at different levels of development that will actually lead to convergence. This is because the less developed economy or institution is then able to imitate technology and methods more easily and cheaply without incurring the initial costs of research and development [

23,

24,

25]. Thus, African countries could extrapolate from this argument to establish more collaborations with the developed world, since the continent can benefit from the “catch up” effect by taking advantage of reduced costs for research and development, which are usually incurred before technological developments can be scaled up, as posited in the Solow model [

26,

27,

28].

Apart from South African and Kenyan universities in general, Makerere University in Uganda, Pan African University (PAU) in Nigeria, Nelson Mandela African Institute of Science and Technology (NM AIST) and University of Dar es Salaam (UDSM) in Tanzania, and more recently the Rwandan universities, African universities do not generally engage in collaborations with educational institutions from the developed world. In fact, at the continental level, African educational and research institutions lag behind in terms of both collaborations and quality research outputs. This results in slow progress towards the attainment of SDGs. Refs. [

29,

30,

31] argued that there has been an improvement with regards to sustainability co-creation, that is, increased willingness to join with societal stakeholders. A similar approach would enrich education and research through transdisciplinary knowledge production and pragmatic solutions [

32].

There is a need to bring awareness and appreciation to the fact that SDGs require a continental approach to avoid the spill-over effect [

19]. There is a usually a tendency for African countries to operate in silos, despite them signalling cooperation through RECs and the African Union (AU). More recent COVID-19 developments are a testament to that; African countries demonstrated little no collaboration, despite the acknowledgement that this is a global pandemic with tangible spill-over effects [

33]. In fact, the underlying “zero-sum” notion upon which such policies are anchored was refuted as far back as 1817, when David Ricardo articulated that all stakeholders stand to gain due to variances in elasticities. Research centres have different specialties (elasticities) and can therefore optimise their gains through collaboration, which in turn improves overall welfare and acceleration towards the attainment of SDGs.

2.2. Governance Issues in Institutions

Governance is a composite term and can thus be viewed from variant angles. These include regulatory quality, rule of law, political stability, voice and accountability, government effectiveness, absence of violence or terrorism and control of corruption. Thus, some countries fare well in some indicators while others struggle in different areas. For instance, although South Africa generally fares well above many African countries, it is rather worrying to note that the country is characterised by declining indicators of governance. Similar to other African nations, South Africa has had incidences of political instability, which introduced high levels of uncertainty, especially during election years and periods of the “Fees must fall” movement. Election campaigns included controversial subjects such as land appropriation with or without compensation, which generally increased investment uncertainty, thereby destabilising macroeconomic conditions. The “Fees must fall” movement not only introduced a shock in terms of the learning periods, but also introduced structural changes as students demanded free education. Some analysts argued that although the notion was noble, it was not sustainable, as it put a fiscal strain on the country. The

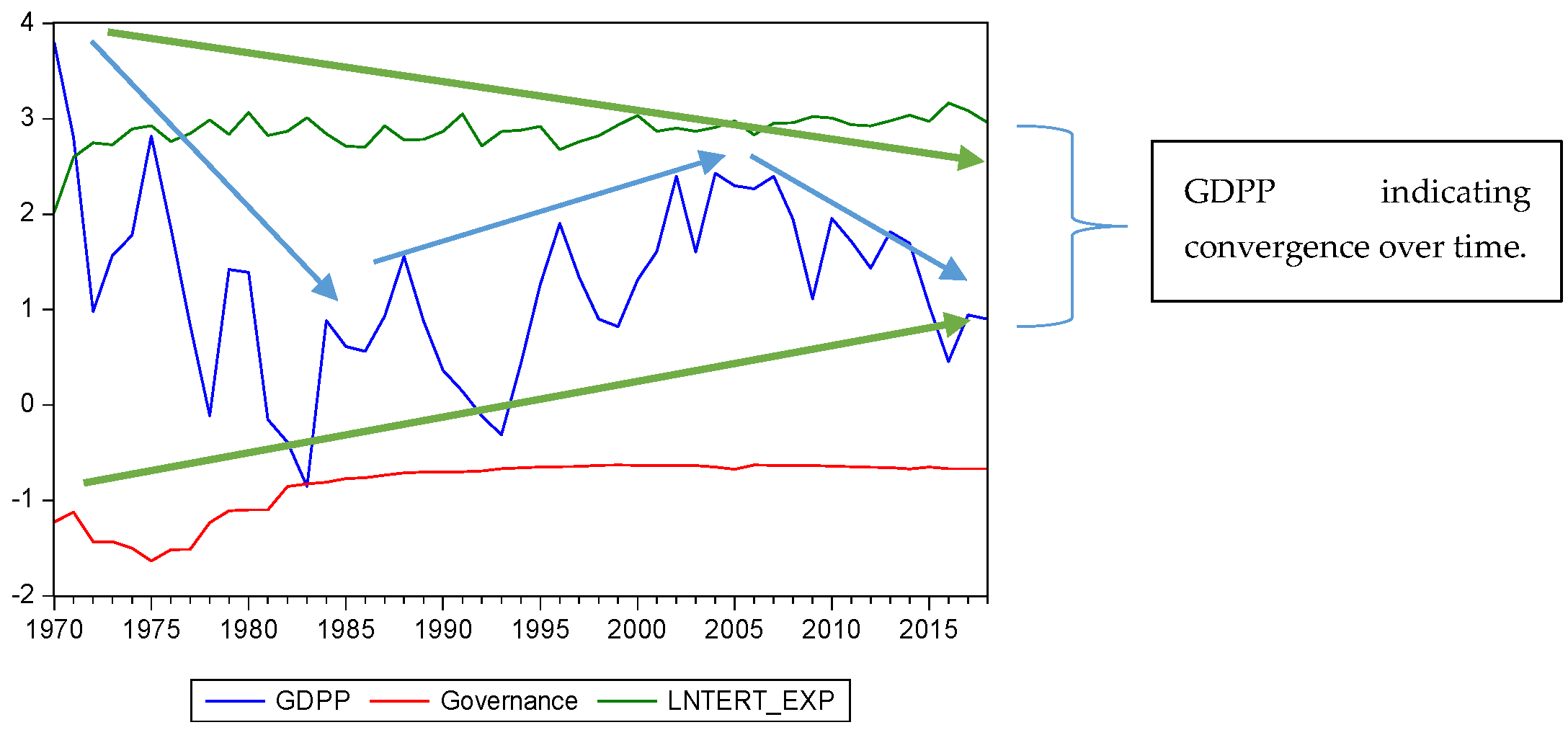

Figure 1 below provides a comparison between the Sub-Saharan African countries and the South African economy.

The figure above clearly shows that regional values are negative, while South Africa has positive values, except for absence of violence and political stability. However, the worrying issue is that the South African values are also declining and converging towards regional averages. This is possibly due to spill-over effects, an argument raised earlier. Similar arguments could be used in economies that are affected by terrorist attacks, such as Nigeria (Boko Haram) and Somalia and Kenya (Al Shabab), and civil war, such as Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Mozambique and Sudan.

The significance of political stability in quality of education cannot be overemphasised. Institutional frameworks in Africa generally are predicated on attitudes of politicians such that, like other policies, SDG projects will live or die with them. In most nations, the Vice-Chancellor and university executive lack independence, as they are appointed by the president, who is usually the Chancellor. Such frameworks are unsustainable due to political instability as a result of politicians who are usually forcibly rejected for various reasons beyond the scope of this paper. The incoming leadership will have no interest in following up on such projects (e.g., SDG-related projects), even if they are aimed at improving the welfare of citizens. The consequences are paralysed institutions [

33,

34,

35,

36]. While there have been notable efforts in South Africa to integrate SDGs with the National Development Plan (NDP), there is little evidence of this synchronisation in most African countries’ national policies. Lozano (2011) argued that political corruption threatens sustainability in education. In Africa, this is deeply entrenched within the structures of the tertiary institutions. Ref. [

37] indicated that although democratisation made governments less secretive, political corruption permeates through endless restructuring exercises that make the domain vulnerable. Consequently, there is routine misconduct in terms of financial misappropriation. This manifests through political solidarity and increased citizen entitlement, sometimes masked as initiatives such as the “Indigenisation policy” in Zimbabwe and the “Broad Based Black Economic Empowerment (BBBEE)” in South Africa, resulting in discriminatory tendering. Unfortunately, educational and research institutions are not spared the chaos.

However, it is not all doom and gloom for the African continent. Botswana has had a fairly impressive performance in its governance indicators since it attained independence in 1966. Recent improvements in some governance indicators such as the control of corruption, government effectiveness and rule of law in countries like Rwanda under Paul Kagame and Tanzania under Dr. John Magufuli has led to some positive outcomes not only in governance but also in quality of tertiary education. Rwandan universities now have several collaborations with regional and international universities. Consequently, the quality of education in these countries has been improving in a sustainable manner. The African Union (AU), which is the higher authority at the continental level, should stimulate regional partnerships in promotion of SDGs. Similar to national educational institutions across the continent, there has been a general sentiment that the AU is failing to provide definitive direction as a higher authority. Historically, the AU failed to address several wars, internal and civil conflicts, and matters relating to memberships in regional economic communities, among others issues [

38,

39]. This resulted in a lack of trust, a key ingredient needed to drive the SDGs. Despite well-documented SDG plans, there has been little pragmatic action, resulting in an uncoordinated approach towards such a common goal. Espousing the wisdom of intergovernmentalism and neoliberalism (Ujupan, 2005), the AU can stimulate the participation of high- and lower-level office bearers. Thus, visionary leadership and proper governance structures are salient elements in the attainment of long-term objectives such as SDGs.