Safe Space, Dangerous Territory: Young People’s Views on Preventing Radicalization through Education—Perspectives for Pre-Service Teacher Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Worldviews and Values in Finnish Education

3. Prevention of Radicalization in Finnish Education

4. Schools as Safe Spaces: Thinking through Dangerous Territory

5. Educational Institutions and Extremism: Young People’s Views

6. Data and Method

7. Results

8. Limitations

9. Discussion

9.1. Safe Spaces in Education

9.2. Sensitive Topics and the Polyphony of Voices in the Safe Spaces

9.3. Teacher Education and the Scaffolding of Safe Spaces

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nurmi, J.; Räsänen, P.; Oksanen, A. The norm of solidarity: Experiencing negative aspects of community life after a school shooting tragedy. J. Soc. Work. 2012, 12, 300–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, D.; Lindekilde, L.; Gøtzsche-Astrup, O. Recognising and responding to radicalisation at the ‘frontline’: Assessing the capability of school teachers to recognise and respond to radicalisation. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, W.; Sieckelinck, S.; Boutellier, H. Preventing Violent Extremism: A Review of the Literature. Stud. Confl. Terror. 2019, 44, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemi, P.-M.; Benjamin, S.; Kuusisto, A.; Gearon, L. How and Why Education Counters Ideological Extremism in Finland. Religions 2018, 12, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieckelinck, S.; Kaulingfreks, F.; De Winter, M. Neither Villains nor Victims: Towards an Educational Perspective on Radicalisation. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 2015, 63, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noddings, N. Peace Education. How We Come to Love and Hate War; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gereluk, D. Education, Extremism and Terrorism. What Should Be Taught in Citizenship Education and Why; Continuum International Publishing Group: Norfolk, Virginia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- García, J.A.R. Islamic religious education and the plan against violent radicalization in Spain. Br. J. Relig. Educ. 2019, 41, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddock, K. British Values and the Prevent Duty in the Early Years. A Practitioner’s Guide; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Tal, D.; Rosen, Y.; Nets-Zehngu, R. Peace Education in Societies Involved in Intractable Conflicts. In Handbook on Peace Education; Salomon, G., Cairns, E., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Di Donato, D.; Grimi, E. (Eds.) Metaphysics of Human Rights1948–2018. On the Occasion of the 70th Anniversary of the UDHR; Vernon Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gearon, L. UNESCO Contemporary Issues in Human Rights Education. From Universal Declaration to World Programme: 1948–2008: 60 Years of Human Rights Education. 2011. pp. 39–104. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002108/210895e.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Gearon, L. Global Human Rights. In The Palgrave International Handbook of Education for Citizenship and Social Justice; Peterson, A., Hattam, R., Zembylas, M., Arthur, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016; pp. 205–228. [Google Scholar]

- Gearon, L. Human Rights RIP: Critique and Possibilities for Human Rights Literacies. In Human Rights Literacies: Future Directions; Roux, C., Becker, A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gearon, L.; Kuusisto, A.; Musaio, M. The Origins and Ends of Human Rights Education: Enduring Problematics, 1948–2018. In Metaphysics of Human Rights 1948–2018; di Donato, L., Grimi, E., Eds.; Vernon Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gearon, L.; Kuusisto, A.; Matemba, Y.; Benjamin, S.; Du Preez, P.; Koirikivi, P.; Simmonds, S. Decolonising the Religious Education Curriculum: International Perspectives in Theory, Research, and Practice, Special Issue. Br. J. Relig. Educ. 2020, 43, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtomäki, E.; Rajala, A. Global education research in Finland. In The Bloomsbury Handbook of Global Education and Learning; Bourn, D., Ed.; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2020; pp. 105–120. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, S.; Koirikivi, P.; Kuusisto, A. Lukiolaisnuorten käsityksiä oppilaitosten roolista väkivaltaisen radikalisoitumisen ennaltaehkäisyssä. Kasvatus 2020, 4, 467–480. [Google Scholar]

- Malkki, L. International Pressure to Perform: Counterterrorism Policy Development in Finland. Stud. Confl. Terror. 2016, 39, 342–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, R.; Chan, W.A.; Manuel, A.; Dilimulati, M. Can education counter violent religious extremism? Can. Foreign Policy J. 2016, 23, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD/PISA. Global Competence Framework. 2018. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/pisa/Handbook-PISA-2018-Global-Competence.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- OSCE. Toledo Guiding Principles on Teaching about Religions and Beliefs in Public Schools. 2007. Available online: http://www.oslocoalition.org/documents/toledo_guidelines.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Riitaoja, A.-L.; Poulter, S.; Kuusisto, A. Worldviews and Multicultural Education in the Finnish Context: A Critical Philosophical Approach to Theory and Practices. Finn. J. Ethn. Migr. 2010, 5, 87–95. Available online: http://www.etmu.fi/fjem/ (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Poulter, S. Kansalaisena Maallistuneessa Maailmassa. Koulun Uskonnonopetuksen Yhteiskunnallisen Tehtävän Tarkastelua. Academic Dissertation, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Poulter, S.; Riitaoja, A.; Kuusisto, A. Thinking multicultural education ‘otherwise’—From a secularist construction towards a plurality of epistemologies and worldviews. Glob. Soc. Educ. 2016, 14, 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusisto, A.; Poulter, S.; Harju-Luukkainen, H. Worldviews and national values in Swedish, Norwegian and Finnish early childhood education and Care curricula. Int. Res. Early Child. Educ. in press.

- Helve, H. A longitudinal perspective on worldviews, values and identities. J. Relig. Educ. 2015, 63, 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utriainen, T.; Ramstedt, T. Uushenkisyys. In Monien Uskontojen ja Katsomusten Suomi; Illman, R., Ketola, K., Latvio, R., Sohlberg, J., Eds.; Kirkon Tutkimuskeskuksen Verkkojulkaisuja, Nro 48, Kirkon Tutkimuskeskus: Tampere, Finland, 2017; pp. 213–223. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelio, J.; Gauthier, F.; Martikainen, T.; Woodhead, L. (Eds.) Routledge International Handbook of Religion in Global Society; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tirri, K. Finland—Promoting ethics and equality. In Research for CULT Committee—Teaching Common Values in Europe: Study; Structural and Cohesion Policies B; Veugelers, W., de Groot, I., Stolk, V., Eds.; European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2017; pp. 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCCBE. National Core Curriculum for Basic Education. Finnish National Agency for Education. Finnish Education in a Nutshell. 2014. Available online: https://www.oph.fi/en/statistics-and-publications/publications/finnish-education-nutshell (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Statistics Finland. Immigrants in the Population. 2019. Available online: https://www.stat.fi/tup/maahanmuutto/maahanmuuttajat-vaestossa_en.html (accessed on 7 March 2021).

- SUOL. Association of Teachers of Religious Education in Finland. Religious Education in Finland. 2019. Available online: https://www.suol.fi/index.php/religious-education-in-finland (accessed on 7 March 2021).

- Ubani, M.; Hyvärinen, E.; Lemettinen, J.; Hirvonen, E. Dialogue, Worldview Inclusivity, and Intra-Religious Diversity: Addressing Diversity through Religious Education in the Finnish Basic Education Curriculum. Religions 2020, 11, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åhs, V.; Poulter, S.; Kallioniemi, A. Preparing for the world of diverse worldviews: Parental and school stakeholder views on integrative worldview education in a Finnish context. Br. J. Relig. Educ. 2017, 41, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics of Finland. Number of Members of the Evangelic Lutheran Church. 2019. Available online: https://www.stat.fi/tup/suoluk/suoluk_vaesto.html (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Lauritzen, S.M.; Nodeland, T.S. What happened and why? Considering the role of truth and memory in peace education curricula. J. Curric. Stud. 2017, 49, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerome, L.; Elwick, A. Teaching about terrorism, extremism and radicalisation: Some implications for controversial issues pedagogy. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2020, 46, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uusitalo, N.; Valaskivi, K. The Attention Apparatus: Conditions and Affordances of News Reporting in Hybrid Media Events of Terrorist Violence. J. Pr. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youth Barometer. 2018. Available online: https://tietoanuorista.fi/nuorisobarometri/nuorisobarometri-2018/ (accessed on 11 March 2021).

- Youth Barometer. 2016. Available online: https://tietoanuorista.fi/nuorisobarometri/nuorisobarometri-2016/ (accessed on 11 March 2021).

- Finnish Ministry of the Interior. National Action Plan for the Prevention of Violent Radicalisation and Extremism. 2020. Available online: https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/162073/SM_2020_1.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y (accessed on 11 March 2021).

- Koirikivi, P.; Benjamin, S.; Kuusisto, A.; Gearon, L. Youths’ resilience and wellbeing in school-based prevention programs. An Investigation from the Finnish Context. In press.

- Youth Barometer. 2019. Available online: https://tietoanuorista.fi/nuorisobarometri/nuorisobarometri-2019/ (accessed on 16 March 2021).

- Statistics Finland. 2020. Available online: https://www.stat.fi/tietotrendit/artikkelit/2020/nuorten-rikollisuus-on-laskussa-mutta-pieni-joukko-nuorista-tekee-yha-enemman-ja-vakavampia-rikoksia/ (accessed on 11 March 2021).

- Kotonen, T. The Soldiers of Odin Finland: From a local movement to an international franchise. In Vigilantism against Migrants and Minorities, Routledge Studies in Fascism and the Far Right; Bjørgo, T., Mareš, M., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019; pp. 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alava, S.; Frau-Meigs, D.; Hassan, G. Youth and Violent Extremism on Social Media: Mapping the Research; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kuusisto, A.; Gearon, L. The Life Trajectory of the Finnish Religious Educator. Relig. Educ. 2017, 44, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almond, B. Education for tolerance: Cultural difference and family values. J. Moral Educ. 2010, 39, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, L. Security, extremism and education: Safe-guarding or surveillance? Br. J. Educ. Stud. 2016, 64, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallinkoski, K.; Benjamin, S.; Koirikivi, P. Prevention of Violent Radicalisation and Extremism in the Education Sector. In Finnish Ministry of the Interior. National Action Plan for the Prevention of Violent Radicalisation and Extremism 2019–2023. Publications of the Finnish Ministry of the Interior 2020, 3, pp. 74–81. Available online: https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/162200/SM_202... (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Grossman, M.; Hadfield, K.; Jefferies, P.; Gerrand, V.; Ungar, M. Youth Resilience to Violent Extremism: Development and Validation of the BRAVE Measure. Terror. Politics Violence 2020, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, A.; Taylor, E.; Karnovsky, S. Moral Disengagement and Building Resilience to Violent Extremism: An Education Intervention. Stud. Confl. Terror. 2014, 37, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Prevent Strategies of Member States. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/networks/radicalisation_awareness_network/ran-and-member-states/repository_en (accessed on 26 February 2021).

- Nguyen, C.T. ECHO CHAMBERS AND EPISTEMIC BUBBLES. Episteme 2020, 17, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, G.W. The Nature of Prejudice; Perseus Books: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Global Citizenship Education. Topics and Learning Objectives. 2015. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000232993 (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Brace, C.; Bailey, A.R.; Harvey, D.C. Religion, place and space: A framework for investigating historical geographies of religious identities and communities. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2006, 30, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stump, R. The Geography of Religion: Faith, Place and Space; Rowan & Littlefield: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Côté-Lussier, C.; Fitzpatrick, C. Feelings of Safety at School, Socioemotional Functioning, and Classroom Engagement. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 58, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, C. (Ed.) Safe Spaces: Human Rights Education in Diverse Contexts; Sense Publications: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gearon, L. Campus Conspiracies: Security and Intelligence Engagement with Universities from Kent State to Counter-Terrorism. J. Beliefs Values 2019, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearon, L. Securitisation Theory and the Securitised University: Europe and the Nascent Colonisation of Global Intellectual Capital. Transform. High. Educ. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearon, L. (Ed.) The Routledge International Handbook of Universities, Security and Intelligence Studies; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kuusisto, A. The Place of Religion in Early Childhood Education and Care. In The Routledge International Handbook for the Place of Religion in Early Childhood Education and Care; Kuusisto, A., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, in press.

- Sjøen, M.M.; Jore, S.H. Preventing extremism through education: Exploring impacts and implications of counter-radicalisation efforts. J. Beliefs Values 2019, 40, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattsson, C.; Säljö, R. Violent Extremism, National Security and Prevention. Institutional Discourses and their Implications for Schooling. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 2018, 66, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragazzi, F. Students as Suspects? The Challenges of Developing Counter-Radicalisation Policies in Education in the Council of Europe Member States; Interim Report; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sian, K.P. Spies, surveillance and stakeouts: Monitoring Muslim moves in British state schools. Race Ethn. Educ. 2015, 18, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattsson, C.; Johansson, T. The hateful other: Neo-Nazis in school and teachers’ strategies for handling racism. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2020, 41, 1149–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, C.; Ellis, B.H.; Lantos, J.D. The Dilemma of Predicting Violent Radicalization. Pediatrrics 2017, 140, e20170685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivenbring, J. Democratic Dilemmas in Education against Violent Extremism. In Policing Schools: School Violence and the Juridification of Youth; Lunneblad, J., Ed.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Faure-Walker, R. Teachers as informants: Countering extremism and promoting violence. J. Beliefs Values 2019, 40, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busher, J.; Choudhury, T.; Thomas, P. The enactment of the counter-terrorism “Prevent duty” in British schools and colleges: Beyond reluctant accommodation or straightforward policy acceptance. Crit. Stud. Terror. 2018, 12, 440–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorcerie, F.; Moignard, B. L’école, la laïcité et le virage sécuritaire post‑attentats: Un tableau contrasté. Sociologie 2017, 4, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van San, M.; Sieckelinck, S.; De Winter, M. Ideals adrift: An educational approach to radicalization. Ethic Educ. 2013, 8, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flensner, K.K.; Von Der Lippe, M. Being safe from what and safe for whom? A critical discussion of the conceptual metaphor of ‘safe space’. Intercult. Educ. 2018, 30, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rom, R.B. ’Safe spaces’: Reflections on an educational metaphor. J. Curric. Stud. 1998, 30, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhabha, H.K. The Location of Culture; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bhabha, H.K.; Ashcroft, B.; Beck, U.; Young, R.; Ikas, K.; Wagner, G. (Eds.) Communicating in the Third Space; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kuusisto, A. Monikulttuurinen luokkahuone kolmantena tilana? Kasvatus 2020, 51, 204–214. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh, T.; Macfarlane, A.; Glynn, T.; Macfarlane, S. Creating peaceful and effective schools through a culture of care. Discourse Stud. Cult. Politicscs Educ. 2012, 33, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, N.S.; Al-Amin, J. Creating Identity-Safe Spaces on College Campuses for Muslim Students. Chang. Mag. High. Learn. 2006, 38, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisse, W. REDCo: A European Research Project on Religion in Education. Relig. Educ. 2010, 37, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzichristou, C.; Lianos, P.; Lampropoulou, A.; Stasinou, V. Individual and Systemic Factors Related to Safety and Relationships in Schools as Moderators of Adolescents’ Subjective Well-Being During Unsettling Times. Contemp. Sch. Psychol. 2020, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.; Schneider, M.; Wornell, C.; Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J. Student’s Perceptions of School Safety. J. Sch. Nurs. 2018, 34, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.; Deci, E. Self-Determination Theory. Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development and Wellness; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Niemiec, C.P.; Ryan, R.M. Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness in the Classroom: Applying Self-Determination Theory to Educational Practice. Theory Res. Educ. 2009, 7, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findikaattori. 2021. Koulutukseen Hakeutuminen 2019. Available online: https://findikaattori.fi/fi/42 (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Kuusisto, A.; Poulter, S.; Kallioniemi, A. Finnish Pupils’ Views on the Place of Religion in School. Relig. Educ. 2017, 112, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virolainen, M.; Tønder, A.H. Progression to higher education from vocational education in Nordic countries: Mixed policies and pathways. In Vocational Education in the Nordic Countries: Learning from Diversity; Jørgensen, C.H., Olsen, O.J., Thunqvist, D.P., Eds.; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2018; pp. 51–73. [Google Scholar]

- Gearon, L. The Totalitarian Imagination: Religion, Politics and Education. In International Handbook of Inter-Religious Education; De Souza, M., Durka, G., Engebretson, K., Gearon, L., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 933–947. [Google Scholar]

- Tirri, K.; Kuusisto, E. Finnish student teachers’ perceptions on the role of purpose in teaching. J. Educ. Teach. 2016, 42, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, J.K.; Clarke, T.J.; Anderson, C.R.; Russell, S.T. Understanding School Safety for Transgender Youth. California Safe Schools Coalition Research Brief No. 13; California Safe Schools Coalition: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy-Levy, S. Introduction. In Peace and Resistance in Youth Cultures. Rethinking Peace and Conflict Studies; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomaa, H. Asevelvollisuus Kansakunnan Rakentajana. Politicsikasta-lehti. 4/2018. 2018. Available online: https://Politicsikasta.fi/asevelvollisuus-kansakunnan-rakentajana/ (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- YLE. Survey: Young People’s will to Defend Their Country Turned to Growth—Support for Universal Conscription also Rises Sharply. News Article in Finnish. 2020. Available online: https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-11179169 (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Maavoimat. Naisten Vapaaehtoiseen Asepalvelukseen Hakeneiden Määrä Kasvussa. 2020. Available online: https://maavoimat.fi/-/naisten-vapaaehtoiseen-asepalvelukseen-hakeneiden-maara-kasvussa (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Lehtonen, J. Going to the ‘Men’s School’? Non-heterosexual and trans youth choosing military service in Finland. Norma 2015, 10, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, S.; Gearon, L.; Kuusisto, A.; Koirikivi, P. Threshold of Adversity: Resilience and the Prevention of Extremism through Education. Nord. Stud. Educ. in press.

- Davies, L. Education and violent extremism: Insights from complexity theory. Educ. Confl. Rev. 2019, 2, 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- Vallinkoski, K.; Koirikivi, P.; Malkki, L. “What is this ISIS all about?” Addressing violent extremism with students: Finnish educators’ perspectives. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besir, D.S.; Nuray, P. A Convergent Parallel Mixed-Methods Study of Controversial Issues in Social Studies Classes: A Clash of Ideologies. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2018, 18, 119–149. [Google Scholar]

- School Health Promotion Study. Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. 2019. Available online: https://www.julkari.fi/handle/10024/140694 (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Feucht, F.C.; Brownlee, J.L.; Schraw, G. Moving Beyond Reflection: Reflexivity and Epistemic Cognition in Teaching and Teacher Education. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 52, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynes, J. Critical Thinking and Cognitive Bias. Informal Log. 2015, 35, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirri, K. Ethical Sensitivity in Teaching and Teacher Education. In Encyclopedia of Teacher Education; Peters, M., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findikaattori. 2020. Available online: https://findikaattori.fi/fi/57#:~:text=Pahoinpitelyj%C3%A4%20ilmoitettiin%20vuonna%202018%20yhteens%C3%A4,Niit%C3%A4%20ilmoitettiin%2023%20700 (accessed on 28 February 2021).

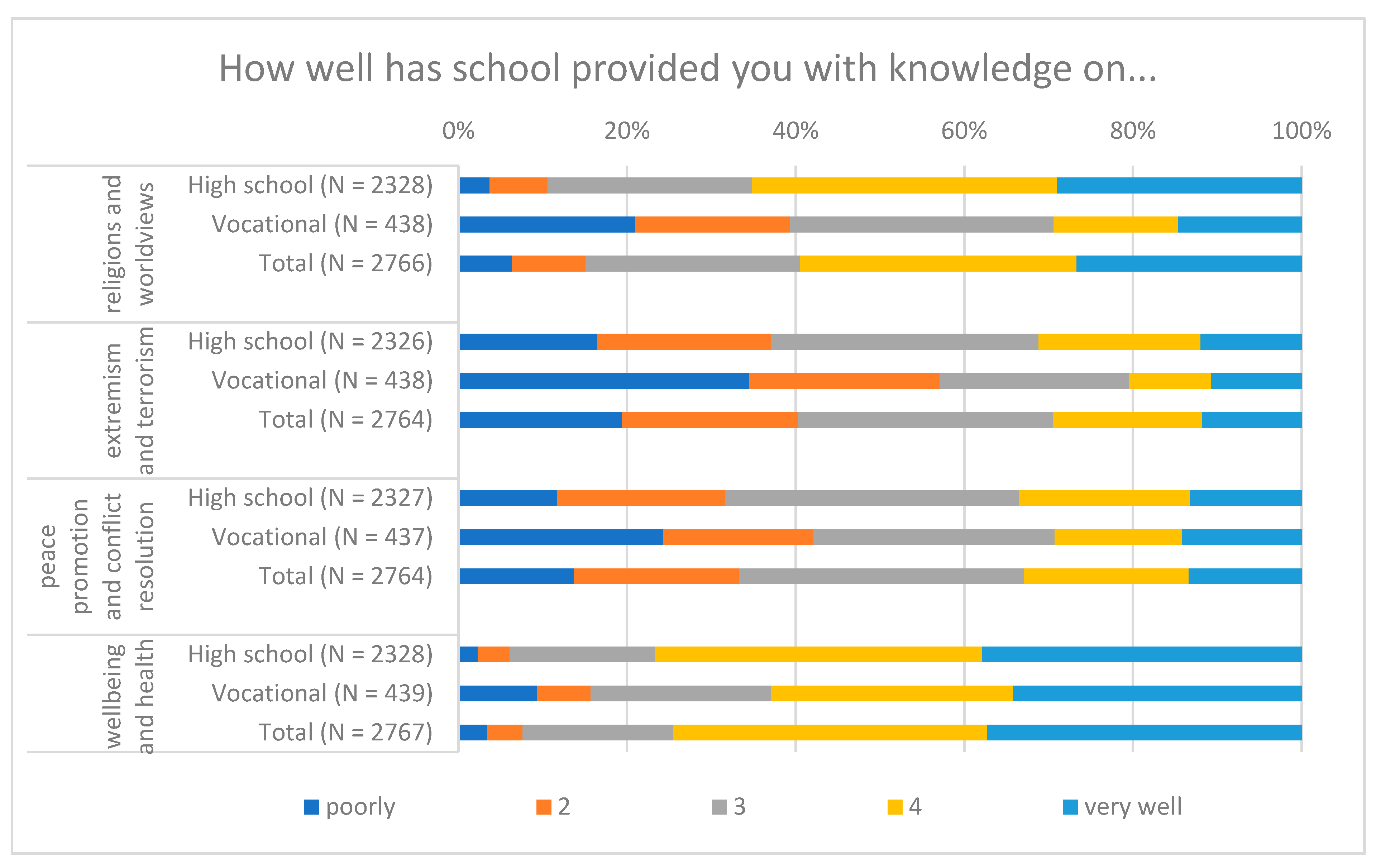

| Religions and Worldviews | Extremism and Terrorism | Peace Promotion and Conflict Resolution | Well-Being and Health | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD. | Mean | SD. | Mean | SD. | Mean | SD. | |

| High school | 3.8 | 1.049 | 2.90 | 1.236 | 3.03 | 1.183 | 4.06 | 0.951 |

| Vocational | 2.84 | 1.317 | 2.40 | 1.332 | 2.77 | 1.349 | 3.72 | 1.256 |

| Total | 3.65 | 1.15 | 2.82 | 1.265 | 2.99 | 1.215 | 4.01 | 1.013 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Benjamin, S.; Salonen, V.; Gearon, L.; Koirikivi, P.; Kuusisto, A. Safe Space, Dangerous Territory: Young People’s Views on Preventing Radicalization through Education—Perspectives for Pre-Service Teacher Education. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 205. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11050205

Benjamin S, Salonen V, Gearon L, Koirikivi P, Kuusisto A. Safe Space, Dangerous Territory: Young People’s Views on Preventing Radicalization through Education—Perspectives for Pre-Service Teacher Education. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(5):205. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11050205

Chicago/Turabian StyleBenjamin, Saija, Visajaani Salonen, Liam Gearon, Pia Koirikivi, and Arniika Kuusisto. 2021. "Safe Space, Dangerous Territory: Young People’s Views on Preventing Radicalization through Education—Perspectives for Pre-Service Teacher Education" Education Sciences 11, no. 5: 205. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11050205

APA StyleBenjamin, S., Salonen, V., Gearon, L., Koirikivi, P., & Kuusisto, A. (2021). Safe Space, Dangerous Territory: Young People’s Views on Preventing Radicalization through Education—Perspectives for Pre-Service Teacher Education. Education Sciences, 11(5), 205. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11050205