1. Beyond Transformational Giftedness

If there is one thing the world needs right now, it is gifted individuals. There are so many problems, ranging from global climate change to pandemics to enormous income disparities to uncontrolled obesity. The world needs gifted individuals to contribute toward the solution of these problems.

How, though, should giftedness be conceptualized? Many conceptions of giftedness have been proposed, a number of which are reviewed immediately below. We, however, have chosen to build upon Sternberg’s notion of transformational vs. transactional giftedness, suggesting that this conception, as it exists, is an excellent start but is missing some elements [

1,

2]. People who are transformationally gifted seek to make positive and meaningful changes to the world, at some level. We have proposed to expand the model and, perhaps, to complete it by considering the concept of transformation in more detail than Sternberg did in his original articles.

2. History of Some Conceptions of Giftedness

The question always is exactly what one means by “gifted”. Over time, scholars have had somewhat different ideas. For example, Sir Francis Galton believed that gifted individuals excel in psychophysical skills, such as recognizing differences between similar visual stimuli or pitches [

3]. He also believed these skills are largely hereditary—passed on from one generation to the next via our genes [

4]. Alfred Binet and Theodore Simon had a very different conception, relating intelligence more to judgmental abilities [

5]. However, Binet and Simon’s primary interest was in children with intellectual challenges rather than in those who were gifted. The challenge of developing Binet’s ideas was taken up by Lewis Terman, a professor at Stanford University, to operationalize Binet and Simon’s ideas for the gifted. Terman adopted the idea of giftedness as recognizable by an IQ of over 140, or roughly 2 ½ standard deviations above the mean score of 100 on the version of Binet’s test he created [

6,

7].

Over the years, many other conceptions of giftedness have evolved. For example, Renzulli proposed that above-average ability, creativity, and task commitment intersect to form giftedness [

8,

9]; Tannenbaum suggested general ability, special aptitudes, non-intellective requisites, environmental supports, and chance in his “sea-star” model [

10]. Some theorists have gone beyond the usual boundaries of such conceptions. For example, Sisk has gone further in her suggestion of a form of spiritual intelligence as a basis for giftedness [

11]. This intelligence was considered but ultimately not included by Gardner in his model of multiple intelligences [

12].

Further, Ziegler has proposed an actiotope model, according to which giftedness is not an internal property of an individual but rather the result of a label assigned by experts that represents interactions that an individual has with the environment [

13]. Gagné has proposed a differentiated model of giftedness and talent (DMGT), according to which one can distinguish the gifts with which one starts life, from talents, which develop out of gifts [

14,

15]. Gagné further distinguishes among intellectual, creative, socio-affective, and sensorimotor abilities, as well as among academic, artistic, business, leisure, social affective, athletic, and technological talents. Dai, in his evolving-complexity theory, suggests that giftedness should be viewed developmentally by treating the developing individual as an open, dynamic, and adaptive system, which changes itself (similarly to Ziegler’s notion) as it interacts with the opportunities as well as the challenges that the environment provides [

16]. Subotnik et al. have proposed a so-called “megamodel,” according to which “giftedness (a) reflects the values of society; (b) is typically manifested in actual outcomes, especially in adulthood; (c) is specific to domains of endeavor; (d) is the result of the coalescing of biological, pedagogical, psychological, and psychosocial factors; and (e) is relative not just to the ordinary (e.g., a child with exceptional art ability compared to peers) but to the extraordinary (e.g., an artist who revolutionizes a field of art)” [

17] (p. 3) [

18]. And Cross and Cross have proposed a school-based conception of giftedness, which emphasizes the various domains of giftedness that schools seek and recognize [

19].

All of these models assume, at some level, that there is an identifiable group of people within the larger population who, one way or another, can be designated as “gifted,” “talented,” or both [

20,

21,

22]. What differs among the models is precisely what set of attributes or behaviors constitutes giftedness, and how context affects the identification of the attributes in that set.

Edited compendia of conceptions of giftedness have been published from time to time by Sternberg and his colleagues [

23,

24,

25,

26]. Histories of conceptions and how they have played out in society have been written by Margolin and by Jolly [

27,

28]. But these conceptions have been variable in how quickly and easily they have taken hold in gifted identification programs in schools. Moreover, the conceptions and the ways they have been implemented sometimes have had racist, classist, or other prejudicial elements (see [

29,

30]).

Most of the models of giftedness that have been proposed have focused on aspects of the person, such as intelligence, creativity, and motivation. Some have included environmental factors as well that either facilitate or hinder the expression of giftedness. Recently, Sternberg has suggested a somewhat different functional account, inspired in part by theories of transactional and transformational leadership [

1,

2,

31,

32,

33].

3. Transformational and Transactional Giftedness

Sternberg has defined transformational giftedness as giftedness that, by its nature, is deployed to make a positive change in the world at some level of analysis [

2]. Transformationally gifted individuals seek to make the world a better place (see also [

34]). People who are transformationally gifted are so by virtue of the function to which they direct their giftedness. They seek to create positive, meaningful, and hopefully, enduring change. In contrast, transactional giftedness is giftedness that is tit-for-tat, representing a form of give and take. A transactionally gifted individual is identified as “gifted” and then is expected to give something back in return. They may be expected to have a string of successes on standardized tests, or to get good grades in school, or to be admitted to prestigious colleges and universities, or to attain prestigious occupational postings and then to excel in them.

Transactional or transformational giftedness do not result merely from someone being born with a particular set of traits. Rather, they result from the kind of give-back the gifted person offers—either an exchange of services (transactional giftedness) or a positive, meaningful, and possibly enduring change in the world. The focus of the current article, however, is on transformational, not transactional giftedness.

The two types of giftedness are not mutually exclusive. Transformationally gifted individuals are often extremely determined to make the positive changes that they wish to make. This kind of resilience helps them to excel in their field. Therefore, most transformationally gifted people are sufficiently transactionally gifted that they can reach a position in society from which they can make the meaningful difference they seek to make. Some programs, such as the Schoolwide Enrichment Model, may help develop aspects of transformational giftedness [

35].

There are many measures of transactional giftedness—virtually all the measures that currently are used to assess giftedness. One might wonder whether transformational giftedness similarly can be measured, or whether it is either immeasurable or measurable only after one’s career is over, and one can assess that career in retrospect. Just as measures of transactional giftedness are actually predictors of transactional giftedness rather than measures of transactional achievement, so, we suggest, is it possible to predict transformational giftedness. The transformational-giftedness scale we are currently exploring in our empirical research is shown in

Table 1. It is taken from Sternberg [

36]. It is available for research purposes for those wishing to use it.

4. Other-Transformational vs. Self-Transformational Giftedness

In reflecting upon the concept of transformational giftedness, we have concluded that the concept needs expansion. In particular, there appear to be two kinds of transformational giftedness that lead to “transformations” in the sense of changing one thing into something different and perhaps very different. Thus, we make a proposal that we believe helps to “complete” Sternberg’s model.

Other-transformational giftedness refers to the direction of one’s giftedness toward making a transformative difference with respect to others—making a positive, meaningful, and possibly enduring difference to the world. This concept appears to be similar to what Sternberg [

1,

2] referred to as transformational giftedness.

Self-transformational giftedness refers to the direction of one’s giftedness toward making a transformative difference with respect to oneself—to making a positive, meaningful, and possibly enduring difference within oneself. For many individuals, self-transformational giftedness is a preliminary to other-transformational giftedness. One finds one’s purpose in life [

37] or in becoming, in Maslow’s terms, self-actualized [

38].

On this view, people do not just simply transform the world at some level. Rather, first, they find a purpose in life—they self-actualize in terms of whatever is meaningful to them [

39]. This purpose and its corresponding goal or set of goals become clear to them. In other words, self-transformational giftedness becomes a base from which transformational giftedness arises.

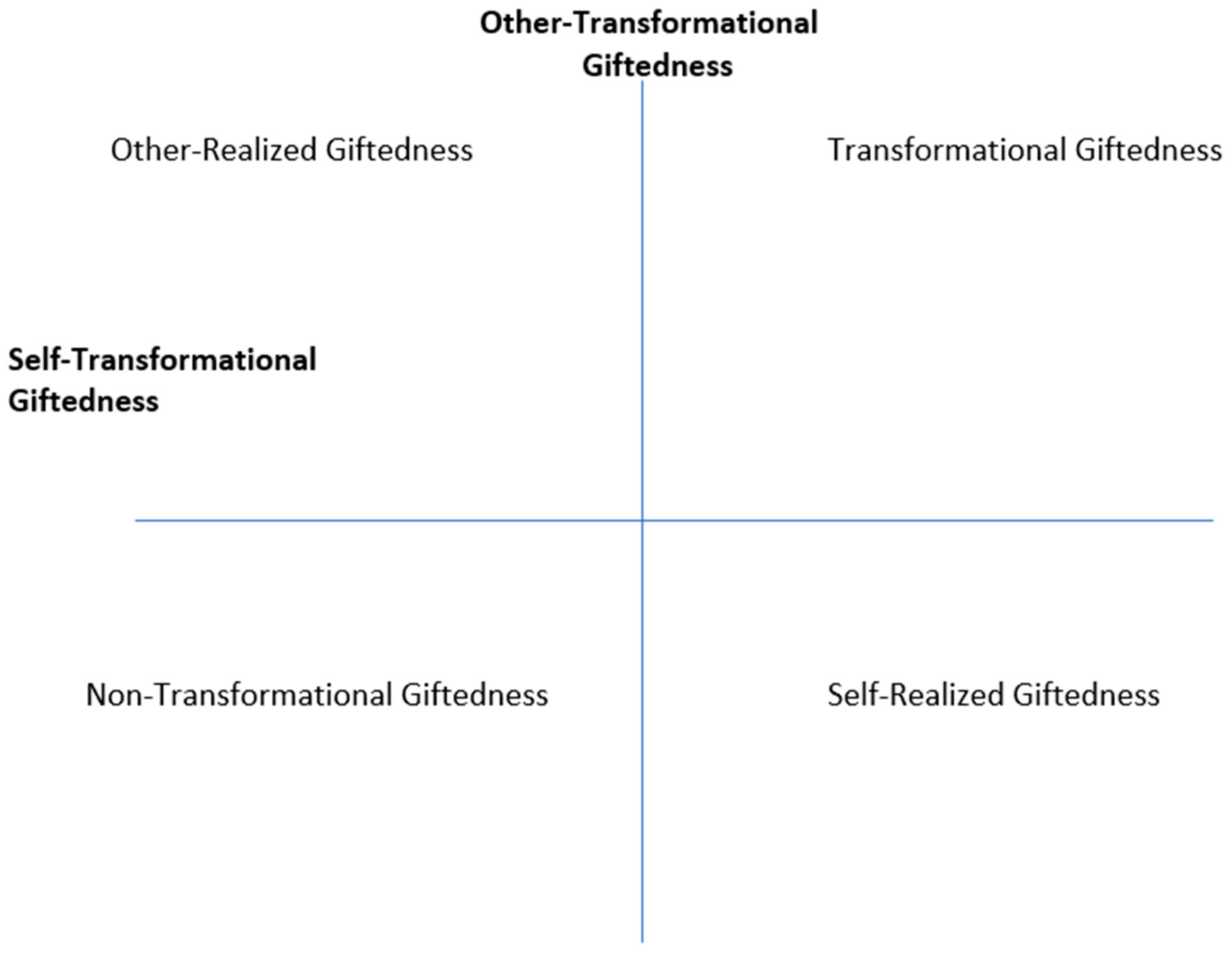

Figure 1 shows our newly proposed model. It links self- and other-transformational giftedness to generate four kinds of functional giftedness.

5. Non-Transformational Giftedness

In the lower-left quadrant, where we have neither other- nor self-transformational giftedness, we have non-transformational giftedness. The giftedness has not been directed toward transformation. Someone in this quadrant may be gifted. Indeed, they may be either inertly or transactionally gifted at any level. They simply lack transformational giftedness of any kind.

Inert giftedness is, perhaps oddly, the kind of giftedness that educational institutions have most emphasized in their identification procedures and in much of their education. Inert giftedness is displayed in having the personal qualities that identify one as gifted but not necessarily as showing any signs of having used these qualities to make any positive and meaningful difference of any kind. One simply possesses identified personal qualities that are sitting in oneself, waiting to be used in some way. Even adults may be inertly gifted. They may have a high IQ or have shown unusual talents on gifted identification measures. But they have not (at least, yet) used their gifts actively. Their last great accomplishment may have been their high scores on a standardized test or their elite university education with which they have done little. Inert giftedness is not shown in

Figure 1, as it is neither self- nor other-transformational.

Inert giftedness is similar, perhaps, to what Renzulli refers to as “schoolhouse giftedness” [

40]. Inert giftedness also is similar to what Gagné has called “outstanding natural abilities” or “gifts” [

14,

15]. And it is similar to Tannenbaum’s notion of “promise” or “potential for gifted fulfillment” [

10]. Gagné and Tannenbaum have viewed giftedness as a developmental concept, whereas inert giftedness is only a starting point, but hopefully not an endpoint, to developing “talent,” in Gagné’s words, or “fulfillment of potential”, in Tannenbaum’s words. Our notion of inert giftedness is similar in that it is a type of giftedness that has not been realized yet. Whatever label one uses, the inertly gifted person has the qualifications to be identified as gifted but stops there because they have not displayed their giftedness in a meaningful societal way.

Transactional giftedness, as noted above, does require some kind of accomplishment. The transactionally gifted individual has given something back—in exchange for their being identified as gifted, they have achieved high grades, or college or university success, or success in a job. But they are in the mode of give-and-take rather than of meaningful change. Transactional giftedness is not shown in

Figure 1, as it is a separate dimension from transformational giftedness. Transformationally gifted individuals almost always know, at some level, how to be transactional when they need to be, but transactionally gifted individuals may or may not be transformationally gifted. Most probably are not. The transactionally gifted person gives back to society, but in a way that requires them to receive something concrete in exchange for what they have given.

6. Transformational Giftedness

Transformational giftedness is represented in the quadrant, in the upper-right, that we have considered above. The individual has transformed themselves—has found their purpose and passion—and has directed themselves toward making the world a better place. They may be adults, of course, as in the case of Martin Luther King, Jr., Albert Einstein, Mother Teresa, or Nelson Mandela. But they also may be adolescents, as in the case of Malala Yousafzai, who was shot for advocating the rights of young women to an education in Pakistan, or Greta Thunberg, who has started a worldwide movement of young people advocating for action to combat climate change. The transformationally gifted person gives without any necessary expectation of a give-back. The main reward for them is the transformation that they hope to help achieve.

Transformational giftedness is not equivalent to mere social engagement or activism. Many social activists simply advocate for causes, following in the possibly admirable, but also well-worn paths of activists who came before them. They echo the messages of others. Like so many people in any other pursuit, you generally never hear about them.

Then there are activists such as those mentioned above—Malala Yousafzai, who at the age of 21 has over 6 million hits on Google; and Greta Thunberg, who, at the age of 18, has roughly 19 million hits on Google. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who at the age of 31 has roughly 14 million hits, turned a career as a progressive social activist into a stint as a Representative in the United States Congress. Some who seek transformation represent a different perspective, such as conservative commentator Ben Shapiro, age 37, with roughly 46 million hits on Google. The point is not the politics or the social activism or whether one believes in their cause, but rather the successful transformation they achieve through their efforts.

7. Self-Realized Giftedness

Self-realized giftedness is represented in the lower-right quadrant of the figure. It refers to people who have transformed themselves to find a sense of purpose and meaning in their lives, but who have not, at least yet, translated this self-transformation into a transformation that also impacts the world at some level. They may simply have not yet gotten to other-transformation, or they may have no desire to get to it. One could imagine, for example, someone who has found a sense of peace, balance, and meaning within their life, but whose sense of purpose simply does not extend, at a given point in their life, to transforming the lives of others. The self-realized gifted person’s gift, in essence, is to themselves. They may find peace and harmony on top of a mountain with no interpersonal contacts, or they may find that peace and harmony in the context of interactions with others. But the gift is in their transformation of self. The interactions may help achieve that transformation but are not the recipients of it.

Who are the famous people with self-realized giftedness? Not many. That is the point: they do not seek fame, but rather, spiritual fulfillment, and often, withdrawal and even isolation. They are content to develop their own self-actualization without seeking fame or other forms of recognition in the world. They may become nuns, or monks, or philosophers on a metaphorical mountaintop. Or they may be next-door neighbors who have achieved self-actualization but have no need or desire to impose it on, or perhaps even share it with, others. They may teach religion or spirituality or yoga or meditation or mindfulness, but their goal is not to make a big splash, but rather to share in a limited way the heights they have reached. The Dalai Lama has been thrust into the role of an ambassador for mindfulness and spirituality but probably has in common many characteristics with those who are self-realized gifted.

8. Other-Realized Giftedness

Other-realized giftedness, represented in the upper-left quadrant of the figure, refers to a realization by people who have made a difference to others but who have not transformed themselves. They are making a difference, but they lack a clear sense of inner direction and purpose. They either may be doing what they are doing because others have put them up to it or because they happened to stumble upon some way in which they can make a difference. But they have not reflected as to why they are doing what they are doing and why it matters for fulfilling themselves and the world. The other-realized gifted person makes a difference to others but may themselves have achieved little or no internal transformation—they direct their gifts fully outwardly, often at the cost of their own self-development.

There are so many examples of people with other-realized giftedness, whose lives have transformed others but at their own expense. Notable examples are popular-music stars such as Elvis Presley, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, and Keith Moon. They made a huge difference to others but utterly failed to get their own lives together. F. Scott Fitzgerald died of alcoholism at age 44 and various other literary geniuses committed suicide, such as Ernest Hemingway, Sylvia Plath, and Virginia Woolf. These individuals transformed the lives of others but never were able to transform their own lives to deal with their greatness, their inner struggles, or both. These individuals made important positive transformations in society, but perhaps at their own expense.

9. Conclusions

We suggest that, if the world is truly to become a better place, we need to develop gifts that are self- and other-transformational. Developing giftedness in children is not just about accelerating them in some subject, or about enriching their learning about that subject matter. Rather, such development is in helping the children find purpose and meaning in their lives and then making a positive, meaningful, and possibly enduring difference to others through the sense of purpose they have developed. To that end, educators and schools may be able to help young individuals develop an understanding of their inner self, guide them to find more purposeful life goals, motivate them to empathize with others and with nature around them, help them develop compassion for others’ suffering, and cultivate attitudes of the inherent oneness that underlies humanity. Schools striving to develop transformational giftedness may not shy away from exposing students to the issues of social injustice and inequity prevalent in human societies.

One can be gifted without being transformationally gifted. But we suggest that if society wants to solve the many problems confronting it, it must develop young people who are not just gifted but gifted in a transformational way. Society must develop the young people who will find meaning in life that will transform them, and then who will make a positive, meaningful, and possibly enduring difference to a world desperately in need of positive change.

Author Contributions

R.J.S. was the lead in conceptualizing the article and wrote the first draft. All other coauthors contributed to the conceptualization and writing, in the order in which they are listed as co-authors. All co-authors reviewed all drafts of the article and revised them as appropriate. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to members of Robert J. Sternberg’s research group at Cornell for occasional discussions of the topic of transformational giftedness.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Summary

Historically, giftedness has been viewed as a single attribute, with the concept of giftedness often operationalized by a minimum IQ score or combination of an IQ score with measures of school achievement. But gifted individuals, as traditionally defined and educated, have not proven up to the task of meeting the grave challenges of contemporary life, such as pandemics, global climate change, weapons of mass destruction, pollution, income disparities, hunger, and repressive governments. We propose that giftedness needs to be conceptualized in a more variegated and practically useful way. For the first time, we propose eight categories of giftedness, which expand upon two categories initially proposed by Robert J. Sternberg. The traditional form of giftedness is viewed as “transactional giftedness,” whereby those identified are expected to give back to society in proportion to the extra resources invested in them. People who are identified but who do not give back are referred to here as “inertly” gifted. We distinguish transactional from transformational giftedness. Self-transformational giftedness involves a positive restructuring of the self; other-transformational giftedness involves restructuring life for others; and fully transformational giftedness involves transforming both the self and others. Giftedness also can be destructive, either of the self, others, or both.

References

- Sternberg, R.J. Transformational giftedness. In Conceptual Frameworks for Giftedness and Talent Development; Cross, T.L., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., Eds.; Prufrock Press: Waco, TX, USA, 2020; pp. 203–234. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, R.J. Transformational giftedness: Rethinking our paradigm for gifted education. Roeper Rev. 2020, 42, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galton, F. Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development (1883); Cornell University Library: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Galton, F. Hereditary Genius; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1869. [Google Scholar]

- Binet, A.; Simon, T. The Development of Intelligence in Children; Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, MA, USA, 1916. [Google Scholar]

- Terman, L.M. The Measurement of Intelligence: An Explanation of and a Complete Guide for the Use of the Stanford Revision and Extension of the Binet-Simon Intelligence Scale; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1916. [Google Scholar]

- Terman, L.M. Genetic Studies of Genius: Mental and Physical Traits of a Thousand Gifted Children; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1925; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Renzulli, J.S. What makes giftedness: Re-examining a definition. Phi Delta Kappan 1978, 60, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzulli, J.S. The three-ring conception of giftedness: A developmental model for promoting creative productivity. In Reflections on Gifted Education: Critical Works by Joseph S. Renzulli and Colleagues; Reis, S.M., Ed.; Prufrock Press: Waco, TX, USA, 2016; pp. 55–90. [Google Scholar]

- Tannenbaum, A.J. Gifted Children: Psychological and Educational Perspectives; Macmillan Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Sisk, D. Engaging the spiritual intelligence of gifted students to build global awareness in the classroom. Roeper Rev. 2008, 30, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, H. Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences, 3rd ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler, A. The actiotope model of giftedness. In Conceptions of Giftedness, 2nd ed.; Sternberg, R.J., Davidson, J.E., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 411–437. [Google Scholar]

- Gagné, F. Motivation within the DMGT 2.0 framework. High Abil. Stud. 2010, 21, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, F. Academic talent development: Theory and best practices. In APA Handbooks in Psychology®. APA Handbook of Giftedness and Talent; Pfeiffer, S.I., Shaunessy-Dedrick, E., Foley-Nicpon, M., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.Y. Evolving complexity theory of talent development. In Conceptual Frameworks for Giftedness and Talent Development; Cross, T.L., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., Eds.; Prufrock Press: Waco, TX, USA, 2020; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Subotnik, R.F.; Olszewski-Kubilius, P.; Worrell, F.C. Rethinking giftedness and gifted education: A proposed direction forward based on psychological science. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2011, 12, 3–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subotnik, R.F.; Olszewski-Kubilius, P.; Worrell, F.C. The talent development megamodel. In Conceptual Frameworks for Giftedness and Talent Development; Cross, T.L., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., Eds.; Prufrock Press: Waco, TX, USA, 2020; pp. 265–288. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, T.L.; Cross, J.R. An enhanced school-based conception of giftedness. In Conceptual Frameworks for Giftedness and Talent Development; Cross, T.L., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., Eds.; Prufrock Press: Waco, TX, USA, 2020; pp. 265–288. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer, S.I. (Ed.) APA Handbook of Giftedness and Talent; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer, S.I. (Ed.) Handbook of Giftedness in Children, 2nd ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, S. Giftedness 101; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, R.J.; Ambrose, D. (Eds.) Conceptions of Giftedness and Talent; Palgrave-Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, R.J.; Davidson, J.E. (Eds.) Conceptions of Giftedness; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, R.J.; Davidson, J.E. (Eds.) Conceptions of Giftedness, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, R.J.; Reis, S.M. (Eds.) Definitions and Conceptions of Giftedness; Corwin: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Margolin, L. Goodness Personified: The Emergence of Gifted Children; Aldine Transaction: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Jolly, J.L. A History of American Gifted Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, J.W. The “precious minority”: Constructing the “gifted” and “academically talented” student in the era of Brown v. Board of Education and the National Defense Education Act. ISIS 2017, 108, 581–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R.J.; Desmet, O.A.; Ford, D.; Gentry, M.L.; Grantham, T.; Karami, S. The legacy: Coming to terms with the origins and development of the gifted-child movement. Roeper Rev. in press.

- Bass, B.M. Transformational Leadership: Industrial, Military, and Educational Impact; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J.; Atwater, L. The Transformational and Transactional Leadership of Men and Women. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 45, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B.M.; Riggio, R.E. Transformational Leadership: A Comprehensive Review of Theory and Research, 2nd ed.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, R.J. ACCEL: A new model for identifying the gifted. Roeper Rev. 2017, 39, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzulli, J.S.; Reis, S. The Schoolwide Enrichment Model: A How-to Guide for Talent Development, 3rd ed.; Prufrock Press: Waco, TX, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, R.J. Transformational vs. transactional deployment of intelligence. J. Intell. 2021, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, S.B. Transcend: The New Science of Self-Actualization; TarcherPerigree: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A. Toward a Psychology of Being; Sublime Books: Floyd, VA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, R.J. Adaptive Intelligence: Surviving and Thriving in Times of Uncertainty; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Renzulli, J.S. Myth: The gifted constitute 3–5% of the population (Dear Mr. and Mrs. Copernicus: We regret to inform you…). Gift. Child Q. 1982, 26, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).