Restorative Justice and the School-to-Prison Pipeline: A Review of Existing Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

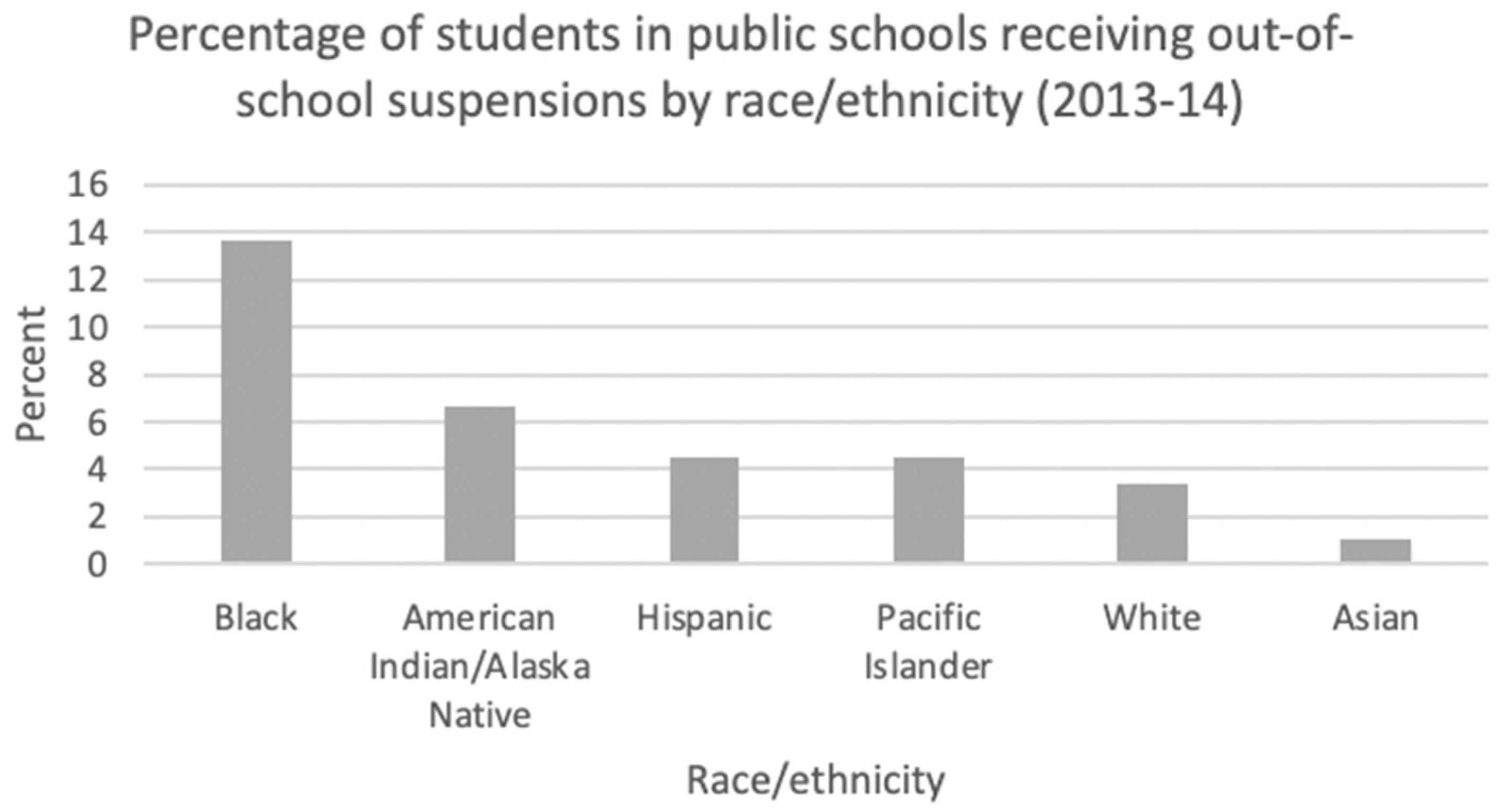

2. Higher Rates of School Suspension

3. Factors Contributing to the School-to-Prison Pipeline

3.1. Biased School Personnel

3.2. Lack of Teacher Preparation and Teacher Support

3.3. Punitive Systems of High-Minority Schools

3.4. Institutional Discrimination

4. Restorative Justice in Schools

4.1. Definition of Restorative Justice

4.2. Origins of Restorative Justice

4.3. Implementation of Restorative Justice in U.S. Schools

4.4. Research on Restorative Justice

- Top-down approaches that lack the values of RJ.

- Approaches based on one restorative practice.

- Colorblind approaches.

- Approaches without adequate support.

- Short-term and under-resourced initiatives.

4.5. Criticisms of Restorative Justice

- It consumes too much time.

- 2.

- It is emotionally depleting.

- 3.

- Teachers should not be involved in RJ.

- 4.

- There is no accountability with RJ.

- 5.

- Agreements are not checked or followed.

- 6.

- RJ is not a valid approach.

- 7.

- Victims need to endure unfair treatment for participating in RJ.

- 8.

- Victims need to forgive those who caused the harm.

- 9.

- RJ leads to resistance and resentment.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Taylor, D.B. George Floyd Protests: A Timeline. 2021. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/article/george-floyd-protests-timeline.html (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Drug Policy Alliance. The Drug War, Mass Incarceration and Race. 2018. Available online: https://drugpolicy.org/resource/drug-war-mass-incarceration-and-race-englishspanish (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Milner, R.H.; Cunningham, H.B.; O’Connor, L.D.; Kestenberg, E.G. These Kids Are Out of Control: Why We Must Reimagine “Classroom Management” for Equity; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer, C.L.; White, M.; Brown, C.M. A Tale of three cities: Defining urban schools within the context of varied geographic areas. Educ. Urban Soc. 2018, 50, 507–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, A.; Evans, K.R. The Starts and Stumbles of Restorative Justice in Education: Where Do We Go from Here? National Education Policy Center: Boulder, CO, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fronius, T.; Darling-Hammond, S.; Sutherland, H.; Guckenburg, S.; Hurley, H.; Petrosino, A. Restorative Justice in U.S. Schools: An Updated Research Review; The WestEd Justice & Prevention Research Center: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics. Status and Trends in the Education of Racial and Ethnic Groups 2018; U.S. Department of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2019.

- U.S. Department of Education. 2013–14 Civil Rights Data Collection: A First Look. 2016. Available online: https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/CRDC2013-14-first-look.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Cuellar, A.E.; Markowitz, S. School suspension and the school-to-prison pipeline. Int. Rev. Law Econ. 2015, 43, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noltemeyer, A.L.; Ward, R.M.; Mcloughlin, C. Relationship between school suspension and student outcomes: A meta-analysis. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 44, 224–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, M.J.; Quinn, D.M.; Dhaliwal, T.K.; Lovison, V.S. Bias in the air: A nationwide exploration of teachers’ implicit racial attitudes, aggregate bias, and student outcomes. Educ. Res. 2020, 49, 566–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, S.N.; Okonofua, J.A. School deferred: When bias affects school leaders. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2020, 11, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, A.; Hafen, C.A.; Ruzek, E.; Mikami, A.Y.; Allen, J.P.; Pianta, R.C. Closing the racial discipline gap in classrooms by changing teacher practice. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 45, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, E.; Butler, B.R. Who cares about diversity? A preliminary investigation of diversity exposure in teacher preparation programs. Multicult. Perspect. 2015, 17, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschfield, P.J. The role of schools in sustaining juvenile justice systems inequality. Future Child. 2018, 28, 11–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, H. The World’s Highest-Scoring Students: How Their Nations Led Them to Excellence; Peter Lang Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, H. Making America #1 in education with three reforms. Clear. House 2020, 93, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, H. The gap in gifted education: Can universal screening narrow it? Education 2020, 140, 207–214. [Google Scholar]

- Starck, J.G.; Riddle, T.; Sinclair, S.; Warikoo, N. Teachers are people too: Examining the racial bias of teachers compared to other American adults. Educ. Res. 2020, 49, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliam, W.S.; Maupin, A.N.; Reyes, C.R.; Accavitti, M.; Shic, F. Do Early Educators’ Implicit Biases Regarding Sex and Race Relate to Behavior Expectations and Recommendations of Preschool Expulsions and Suspensions; Yale University Child Study Center: New Haven, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, H. The lack of minority students in gifted education: Hiring more exemplary teachers of color can alleviate the problem. Clear. House 2019, 4–5, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollnick, D.M.; Chinn, P.C. Multicultural Education in a Pluralistic Society; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gayle-Evans, G.; Michael, D. A study of pre-service teachers’ awareness of multicultural issues. Multicult. Perspect. 2006, 8, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.P.; Margolius, M.; Rollock, M.; Yan, C.T.; Cole, M.L.; Zaff, J.F. Disciplined and Disconnected: How Students Experience Exclusionary Discipline in Minnesota and the Promise of Non-Exclusionary Alternatives; America’s Promise Alliance: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ACLU. Bullies in Blue: Origins and Consequences of School Policing; American Civil Liberties Union: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hanford, E.U.S. High School Graduation Rate Is Up—But There’s a Warning Label Attached. 2016. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2016/10/27/u-s-high-school-graduation-rate-is-up-but-theres-a-warning-label-attached/ (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Hanson, K.; Stipek, D. Schools V. Prisons: Education’s the Way to Cut Prison Population; Stanford Graduate School of Education: Stanford, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, E. Teaching with Poverty in Mind; ASCD: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, K. Education Opportunities in Prison Are Key to Reducing Crime; Center for American Progress: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/education-k-12/news/2018/03/02/447321/education-opportunities-prison-key-reducing-crime/ (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Long, C. Restorative Discipline Makes Huge Impact in Texas Elementary and Middle Schools. 2016. Available online: https://www.nea.org/advocating-for-change/new-from-nea/restorative-discipline-makes-huge-impact-texas-elementary-and (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Walker, T. Restorative Practices in Schools Work ... But They Can Work Better. 2020. Available online: https://www.nea.org/advocating-for-change/new-from-nea/restorative-practices-schools-work-they-can-work-better (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Mirsky, L. Restorative Justice Practices of Native American, First Nation and Other Indigenous People of North America: Part One. 2004. Available online: https://www.iirp.edu/news/restorative-justice-practices-of-native-american-first-nation-and-other-indigenous-people-of-north-america-part-one (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Wilson, D.B.; Olaghere, A.; Kimbrell, C.S. Effectiveness of Restorative Justice Principles in Juvenile Justice: A Meta-Analysis; George Mason University: Fairfax, VA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudreault, A. The Limits of Restorative Justice. 2005. Available online: https://www.victimsweek.gc.ca/symp-colloque/past-passe/2009/presentation/arlg_1.html (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Hanan, E. Decriminalizing violence: A critique of restorative justice and proposal for diversionary mediation. N. M. Law Rev. 2016, 46, 123–170. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubansky, M. Nine Criticisms of School Restorative Justice. Available online: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/between-the-lines/201903/nine-criticisms-school-restorative-justice (accessed on 15 February 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morgan, H. Restorative Justice and the School-to-Prison Pipeline: A Review of Existing Literature. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11040159

Morgan H. Restorative Justice and the School-to-Prison Pipeline: A Review of Existing Literature. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(4):159. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11040159

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorgan, Hani. 2021. "Restorative Justice and the School-to-Prison Pipeline: A Review of Existing Literature" Education Sciences 11, no. 4: 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11040159

APA StyleMorgan, H. (2021). Restorative Justice and the School-to-Prison Pipeline: A Review of Existing Literature. Education Sciences, 11(4), 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11040159