Can a Questionnaire Be Useful for Assessing Reading Skills in Adults? Experiences with the Adult Reading Questionnaire among Incarcerated and Young Adults in Norway

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study 1

2.1. Methods and Measurements

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Measurements

2.1.3. Procedure for Study 1

2.2. Results from Study 1

2.2.1. Principal Component Analysis

2.2.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

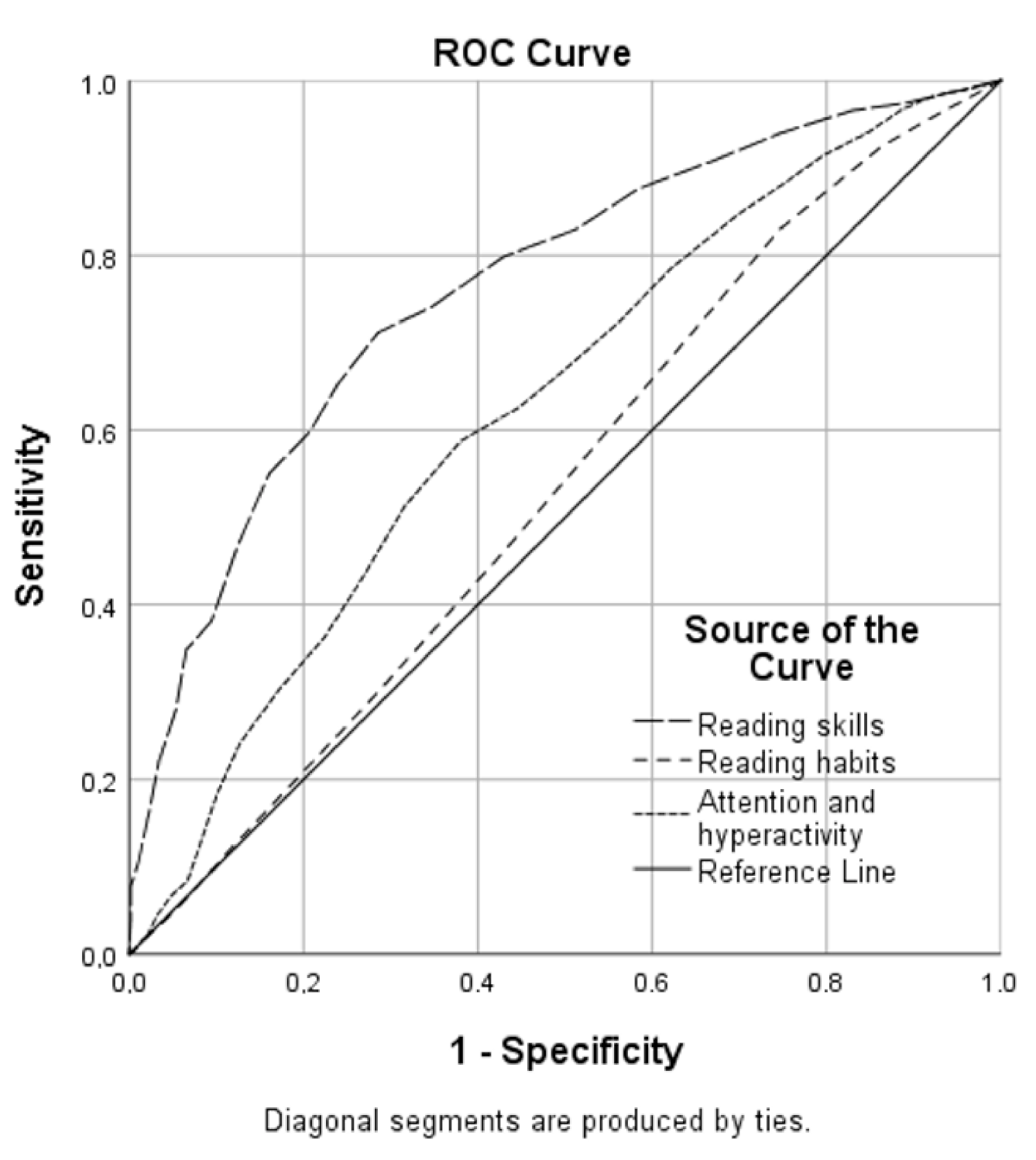

2.2.3. The Discriminative Properties of the Reading Questionnaire

2.3. Discussion of Study 1

3. Study 2

3.1. Method and Measurements

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Measures

3.1.3. Procedure of Study 2

3.2. Results of Study 2

3.2.1. Principal Component Analysis

3.2.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.2.3. The Discriminative Properties of the Reading Questionnaire

3.3. Discussion of Study 2

4. General Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gabrielsen, E. Slik Leser Voksne i Norge. en Kartlegging av Leseferdigheten i Aldersgruppen 16–65 År; Senter for Leseforsking: Stavanger, Norway, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielsen, E. Hvor godt må vi kunne lese for å fungere i dagens samfunn? Samfunnsspeilet 2005, 2, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, L.Ø.; Varberg, J.; Manger, T.; Eikeland, O.-J.; Asbjørnsen, A. Reading and writing self-efficacy of incarcerated adults. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2012, 22, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, J.; Reid, G. An examination of the relationship between dyslexia and offending in young people and the implications for the training system. Dyslexia 2001, 7, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, K.; Almvik, R.; Levander, S. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, reading disability, and personality disorders in a prison population. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law 2001, 29, 186–193. [Google Scholar]

- Samuelsson, S.; Herkner, B.; Lundberg, I. Reading and writing difficulties among prison inmates: A matter of experiential factors rather than dyslexic problems. Sci. Stud. Read. 2003, 7, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanford, R.; Foster, J.E. Reading, writing, and prison education reform? The tricky and political process of establishing college programs for prisoners: Perspectives from program developers. Equal. Oppor. Int. 2006, 25, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowling, M.J.; Adams, J.W.; Bowyer-Crane, C.; Tobin, V. Levels of literacy among juvenile offenders: The incidence of specific reading difficulties. Crim. Behav. Ment. Health 2000, 10, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.; Kett, M. The Prison Adult Literacy Survey. Results and Implications; Irish Prison Service: Dublin, Ireland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J.; Meehl, P.E. Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychol. Bull. 1955, 52, 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, D.G.; Bland, J.M. Statistics notes: Diagnostic tests 1: Sensitivity and specificity. BMJ 1994, 308, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education. Act relating to Primary and Secondary Education and Training (The Education Act); Ministry of Education: Oslo, Norway, 2020.

- Christie, N. Modeller for fengselsorganisasjonen (Prison Organization Models). In I Stedet for Fengsel; Østensen, R., Ed.; Pax Forlag: Oslo, Norway, 1970; pp. 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Kriminalomsorgen. Kriminalomsorgens Årsstatistikk 2019; Kriminalomsorgsdirektoratet: Oslo, Norway, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Justice and Public Security. Act Relating to the Execution of Sentences etc. (The Execution of Sentences Act); Ministry of Justice and Public Security: Oslo, Norway, 2021.

- Eikeland, O.-J.; Manger, T.; Asbjørnsen, A.E. Nordmenn i Fengsel: Utdanning, Arbeid Og Kompetanse; Fylkesmannen i Hordaland, Utdanningsavdelinga: Bergen, Norway, 2013; p. 90. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, L.Ø.; Asbjørnsen, A.E.; Manger, T.; Eikeland, O.-J. An examination of the relationship between self-reported and measured reading and spelling skills among incarcerated adults in Norway. J. Correct. Educ. 2011, 62, 26–50. [Google Scholar]

- Asbjørnsen, A.E.; Eikeland, O.-J.; Manger, T. Innsatte i Norske Fengsel: Leseferdigheter og Oppmerksomhetsvansker; Fylkesmannen i Hordaland: Bergen, Norway, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, I. Reading and writing disabilities among inmates in correctional settings. A Swedish perspective. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2011, 21, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Søndenaa, E.; Rasmussen, K.; Palmstierna, T.; Nøttestad, J. The prevalence and nature of intellectual disability in Norwegian prisons. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2008, 52, 1129–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanford, S.; Muhammad, B. The confluence of language and learning disorders and the school-to-prison pipeline among minority students of color: A critical race theory. Am. Univ. J. Gend. Soc. Policy Law 2017, 26, 691. [Google Scholar]

- Bhuller, M.; Dahl, G.B.; Løken, K.V.; Mogstad, M. Incarceration, Recidivism and Employment; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016.

- Davis, L.; Steele, J.; Bozick, R.; Williams, M.; Turner, S.; Miles, J.; Saunders, J.; Steinberg, P. How Effective Is Correctional Education, and Where Do We Go from Here? The Results of a Comprehensive Evaluation; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lochner, L.; Moretti, E. The Effect of Education on Crime: Evidence from Prison Inmates, Arrests, and Self-Reports. Am. Econ. Rev. 2004, 94, 155–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swisher, R.R.; Dennison, C.R. Educational Pathways and Change in Crime Between Adolescence and Early Adulthood. J. Res. Crime Delinq. 2016, 53, 840–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steurer, S.J.; Smith, L.G. Education Reduces Crime: Three-State Recidivism Study—Executive Summary; Correctional Education Association: Elk Ridge, UT, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brosens, D.; De Donder, L.; Dury, S.; Verté, D. Barriers to participation in vocational orientation programmes among prisoners. J. Prison. Educ. Reentry 2015, 2, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, L.; Bozick, R.; Steele, J.; Saunders, J.; Miles, J. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Correctional Education: A Meta-Analysis of Programs That Provide Education to Incarcerated Adults; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Grigorenko, E.L. Learning disabilities in juvenile offenders. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2006, 15, 353–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eikeland, O.-J.; Manger, T.; Asbjørnsen, A. Norske Innsette: Utdanning, Arbeid, Ønske og Planar; Fylkesmannen i Hordaland: Bergen, Norway, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Asbjørnsen, A.E.; Jones, L.Ø.; Munkvold, L.H.; Obrzut, J.E.; Manger, T. An examination of shared variance in self-report and objective measures of attention in the incarcerated adult population. J. Atten. Disord. 2010, 14, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snow, P.C. Speech-language pathology and the youth offender: Epidemiological overview and roadmap for future speech-language pathology research and scope of practice. Lang. Speech Hear. Serv. Sch. 2019, 50, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morken, F.; Jones, L.Ø.; Helland, W.A. Disorders of language and literacy in the prison population: A scoping review. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimons, D. Pausing Mid-Sentence: Young Offender Perspectives on their Language and Communication Needs; Queen Margaret University: Edinburgh, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Snowling, M.; Dawes, P.; Nash, H.; Hulme, C. Validity of a protocol for adult self-report of dyslexia and related difficulties. Dyslexia 2012, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smythe, I.; Everatt, J. Adult dyslexia checklist. In The Dyslexia Handbook; Smythe, I., Ed.; British Dyslexia Association: Reading, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R.C.; Adler, L.A.; Gruber, M.J.; Sarawate, C.A.; Spencer, T.; Van Brunt, D.L. Validity of the World Health Organization Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS) Screener in a representative sample of health plan members. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2007, 16, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinegrad, M. A Revised adult dyslexia check list. Educare 1994, 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R.C.; Adler, L.; Ames, M.; Demler, O.; Faraone, S.; Hiripi, E.; Howes, M.J.; Jin, R.; Secnik, K.; Spencer, T.; et al. The World Health Organization adult ADHD self-report scale (ASRS): A short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychol. Med. 2005, 35, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Jamovi Project. Jamovi, (Version 1.6.8); [Computer Software]. 2021. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; Version 25.0.; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kriminalomsorgsdirektoratet. Kriminalomsorgens Årsstatistikk—2016; Kriminalomsorgsdirektoratet: Oslo, Norway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stokkeland, L.; Fasmer, O.B.; Waage, L.; Hansen, A.L. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among inmates in Bergen Prison. Scand. J. Psychol. 2014, 55, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rösler, M.; Retz, W.; Retz-Junginger, P.; Hengesch, G.; Schneider, M.; Supprian, T.; Schwitzgebel, P.; Pinhard, K.; Dovi-Akue, N.; Wender, P.; et al. Prevalence of attention deficit–/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and comorbid disorders in young male prison inmates. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2004, 254, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsberg, Y.; Hirvikoski, T.; Lindefors, N. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) among longer-term prison inmates is a prevalent, persistent and disabling disorder. BMC Psychiatry 2010, 10, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalteg, A.; Gustafsson, P.; Levander, S. Hyperactivity syndrome is common among prisoners. ADHD not only a pediatric psychiatric diagnosis. Lakartidningen 1998, 95, 3078–3080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Einarsson, E.; Sigurdsson, J.F.; Gudjonsson, G.H.; Newton, A.K.; Bragason, O.O. Screening for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and co-morbid mental disorders among prison inmates. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2009, 63, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, B.F.; Groisser, D.; Welsh, M.C. Contrasting cognitive deficits in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder versus reading disability. Dev. Psychol. 1993, 29, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaywitz, B.A.; Fletcher, J.M.; Shaywitz, S.E. Defining and Classifying Learning Disabilities and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J. Child. Neurol. 1995, 10, S50–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaywitz, E.S.; A Shaywitz, B.; Fletcher, J.; Shupack, H. Evaluation of school performance: Dyslexia and attention deficit disorder. Pediatrics 1986, 13, 96–107. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, J.; Rich, R. Facing Learning Disabilities in the Adult Years. Understanding Dyslexia, ADHD, Assessment, Intervention, and Research; Oxford University Press: Cary, NC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, F.L.; Morris, M.K.; Morris, R. Naming and verbal memory skills in adults with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Reading Disability. J. Clin. Psychol. 2001, 57, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vellutino, F.R.; Fletcher, J.M.; Snowling, M.J.; Scanlon, D.M. Specific reading disability (dyslexia): What have we learned in the past four decades? J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2004, 45, 2–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hugo, M. Meningsfullt Lärande in Skolverksamheten på Särskilda Ungdomshem; Statens insitutionsstyrelse SiS: Stockholm, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Asbjørnsen, A.E.; Jones, L.Ø.; Eikeland, O.-J.; Manger, T. Spørreskjema om voksnes lesing (SLV) som screeninginstrument for leseferdigheter: Erfaringer fra bruk i en survey blant norske innsatte. Logopeden. Tidsskrift for Norsk Logopedlag 2016, 3, 14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Corballis, M.C.; Beale, I.L. Orton revisited: Dyslexia, laterality, and left-right confusion. In Visual Processes in Reading and Reading Disabilities; Dale, M., Willows, R.S.K., Evelyne Corcos, Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1993; pp. 57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, D.F.; Geschwind, N. Gerstmann’s syndrome. Neurology 1970, 20, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaywitz, S.E.; Mody, M.; Shaywitz, B.A. Neural mechanisms in dyslexia. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 15, 278–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofte, S.H.; Hugdahl, K. Rightleft discrimination in male and female, young and old subjects. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2002, 24, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirnstein, M.; Bayer, U.; Ellison, A.; Hausmann, M. TMS over the left angular gyrus impairs the ability to discriminate left from right. Neuropsychology 2011, 49, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sholl, M.J.; Egeth, H.E. Right-left confusion in the adult: A verbal labeling effect. Mem. Cogn. 1981, 9, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Without Dyslexia (n = 168) | With Dyslexia (n = 77) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Item Description | Mean | Sd. | Mean | Sd. |

| ARQ1 | How would you consider your reading skills? | 2.77 | 0.97 | 1.70 | 0.80 |

| ARQ2 | How would you consider your writing skills? | 1.24 | 0.90 | 2.32 | 0.70 |

| ARQ3 | Do you experience any difficulties reading? | 0.73 | 0.93 | 2.09 | 0.78 |

| ARQ4 | How often do you have to read during your day-to-day activities? | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.96 | 0.99 |

| ARQ5 | I find it difficult to read words I haven’t seen before | 1.63 | 0.89 | 2.89 | 0.95 |

| ARQ6 | I find it difficult to read aloud | 1.34 | 1.15 | 2.71 | 1.06 |

| ARQ7 | I struggle to find the right words when I speak | 1.77 | 0.90 | 2.21 | 0.98 |

| ARQ8 | I mix up or get the names of objects wrong | 1.15 | 0.79 | 1.92 | 0.99 |

| ARQ9 | I get right and left mixed up | 1.10 | 1.17 | 1.94 | 1.30 |

| ARQ10 | I have problems planning my time | 1.47 | 1.01 | 1.75 | 1.02 |

| ARQ11 | How often do you have to write during your day-to-day activities? | 1.28 | 0.95 | 1.39 | 1.12 |

| ASRS1 | How often do you have trouble wrapping up the fine details of a project, once the challenging parts have been done? | 1.87 | 0.86 | 1.97 | 1.04 |

| ASRS2 | How often do you have difficulty getting things in order when you have to do a task that requires organization? | 1.48 | 0.91 | 1.75 | 0.96 |

| ASRS3 | How often do you have problems remembering appointments or obligations? | 1.17 | 0.86 | 1.24 | 0.92 |

| ASRS4 | When you have a task that requires a lot of thought, how often do you avoid or delay getting started? | 2.08 | 0.90 | 2.03 | 1.03 |

| ASRS5 | How often do you fidget or squirm with your hands or feet when you have to sit down for a long time? | 2.61 | 1.09 | 2.47 | 1.14 |

| ASRS6 | How often do you feel overly active and compelled to do things, like you were driven by a motor? | 1.86 | 1.01 | 1.97 | 1.11 |

| Component Loadings | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | ||||||

| Item | Item Description | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Uniqueness |

| ARQ6 | I find it difficult to read aloud | 0.821 | 0.268 | |||

| ARQ5 | I find it difficult to read words I haven’t seen before | 0.819 | 0.276 | |||

| ARQ7 | I struggle to find the right words when I speak | 0.804 | 0.290 | |||

| ARQ8 | I mix up or get the names of objects wrong | 0.685 | 0.481 | |||

| ARQ9 | I get right and left mixed up | 0.603 | 0.508 | |||

| ASRS2 | How often do you have difficulty getting things in order when you have to do a task that requires organization? | 0.758 | 0.380 | |||

| ASRS1 | How often do you have trouble wrapping up the fine details of a project, once the challenging parts have been done? | 0.756 | 0.418 | |||

| ASRS3 | How often do you have problems remembering appointments or obligations? | 0.735 | 0.440 | |||

| ARQ10 | I have problems planning my time | 0.720 | 0.379 | |||

| ASRS4 | When you have a task that requires a lot of thought, how often do you avoid or delay getting started? | 0.660 | 0.509 | |||

| ARQ4 | How often do you have to read during your day-to-day activities? | 0.892 | 0.197 | |||

| ARQ11 | How often do you have to write during your day-to-day activities? | 0.872 | 0.237 | |||

| ASRS6 | How often do you feel overly active and compelled to do things, like you were driven by a motor? | 0.857 | 0.251 | |||

| ASRS5 | How often do you fidget or squirm with your hands or feet when you have to sit down for a long time? | 0.654 | 0.428 | |||

| without Dyslexia (n = 990) | with Dyslexia (n = 347) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Item Description | Mean | Sd. | Mean | Sd. |

| ARQ1 | How would you consider your reading skills? | 0.80 | 0.86 | 1.68 | 1.12 |

| ARQ2 | How would you consider your writing skills? | 1.00 | 0.94 | 1.97 | 1.14 |

| ARQ3 | Do you experience any difficulties reading? | 0.46 | 0.79 | 1.40 | 1.06 |

| ARQ4 | How often do you have to read during your day-to-day activities? | 1.86 | 1.18 | 2.03 | 1.11 |

| ARQ5 | I find it difficult to read words I haven’t seen before | 0.89 | 0.91 | 1.77 | 1.15 |

| ARQ6 | I find it difficult to read aloud | 1.05 | 1.15 | 2.03 | 1.28 |

| ARQ7 | I struggle to find the right words when I speak | 1.24 | 1.01 | 1.67 | 1.09 |

| ARQ8 | I mix up or get the names of objects wrong | 0.88 | 0.87 | 1.32 | 1.04 |

| ARQ9 | I get right and left mixed up | 0.32 | 0.69 | 0.64 | 0.98 |

| ARQ10 | I have problems planning my time | 1.22 | 1.08 | 1.60 | 1.12 |

| ARQ11 | How often do you have to write during your day-to-day activities? | 2.21 | 1.15 | 2.33 | 1.06 |

| ASRS1 | How often do you have trouble wrapping up the fine details of a project, once the challenging parts have been done? | 1.51 | 1.07 | 1.76 | 1.13 |

| ASRS2 | How often do you have difficulty getting things in order when you have to do a task that requires organization? | 1.37 | 0.99 | 1.64 | 1.07 |

| ASRS3 | How often do you have problems remembering appointments or obligations? | 1.35 | 1.01 | 1.68 | 1.13 |

| ASRS4 | When you have a task that requires a lot of thought, how often do you avoid or delay getting started? | 1.60 | 1.06 | 1.84 | 1.06 |

| ASRS5 | How often do you fidget or squirm with your hands or feet when you have to sit down for a long time? | 1.97 | 1.28 | 2.56 | 1.20 |

| ASRS6 | How often do you feel overly active and compelled to do things, like you were driven by a motor? | 1.72 | 1.27 | 2.22 | 1.21 |

| Component Loadings | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | |||||

| Item | Item Description | 1 | 2 | 3 | Uniqueness |

| ASRS5 | How often do you fidget or squirm with your hands or feet when you have to sit down for a long time? | 0.757 | 0.414 | ||

| ASRS1 | How often do you have trouble wrapping up the fine details of a project, once the challenging parts have been done? | 0.750 | 0.393 | ||

| ASRS4 | When you have a task that requires a lot of thought, how often do you avoid or delay getting started? | 0.742 | 0.374 | ||

| ASRS2 | How often do you have difficulty getting things in order when you have to do a task that requires organization? | 0.710 | 0.393 | ||

| ASRS3 | How often do you have problems remembering appointments or obligations? | 0.707 | 0.439 | ||

| ASRS6 | How often do you feel overly active and compelled to do things, like you were driven by a motor? | 0.702 | 0.499 | ||

| ARQ10 | I have problems planning my time | 0.671 | 0.425 | ||

| ARQ5 | I find it difficult to read words I haven’t seen before | 0.785 | 0.362 | ||

| ARQ8 | I mix up or get the names of objects wrong | 0.744 | 0.383 | ||

| ARQ6 | I find it difficult to read aloud | 0.742 | 0.386 | ||

| ARQ7 | I struggle to find the right words when I speak | 0.737 | 0.416 | ||

| ARQ9 | I get right and left mixed up | 0.453 | 0.746 | ||

| ARQ11 | How often do you have to write during your day-to-day activities? | 0.906 | 0.177 | ||

| ARQ4 | How often do you have to read during your day-to-day activities? | 0.895 | 0.191 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Asbjørnsen, A.E.; Jones, L.Ø.; Eikeland, O.J.; Manger, T. Can a Questionnaire Be Useful for Assessing Reading Skills in Adults? Experiences with the Adult Reading Questionnaire among Incarcerated and Young Adults in Norway. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11040154

Asbjørnsen AE, Jones LØ, Eikeland OJ, Manger T. Can a Questionnaire Be Useful for Assessing Reading Skills in Adults? Experiences with the Adult Reading Questionnaire among Incarcerated and Young Adults in Norway. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(4):154. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11040154

Chicago/Turabian StyleAsbjørnsen, Arve E., Lise Øen Jones, Ole Johan Eikeland, and Terje Manger. 2021. "Can a Questionnaire Be Useful for Assessing Reading Skills in Adults? Experiences with the Adult Reading Questionnaire among Incarcerated and Young Adults in Norway" Education Sciences 11, no. 4: 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11040154

APA StyleAsbjørnsen, A. E., Jones, L. Ø., Eikeland, O. J., & Manger, T. (2021). Can a Questionnaire Be Useful for Assessing Reading Skills in Adults? Experiences with the Adult Reading Questionnaire among Incarcerated and Young Adults in Norway. Education Sciences, 11(4), 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11040154