Parental (STEM) Occupations, the Home Numeracy Environment, and Kindergarten Children’s Numerical Competencies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Family’s Socioeconomic Status and Children’s Early Numerical Competencies

1.2. Parental Occupation and Other Aspects of Socioeconomic Status

1.3. Home Numeracy Environment

1.4. Early Development of Numerical Competencies in the Home

1.5. The Present Study

- (1)

- We hypothesize that parents’ learned STEM vs. non-STEM occupations are associated with the HNE and with children’s numerical competencies. Here, the HNE acts as a mediator.

- We hypothesize that parents’ learned STEM vs. non-STEM occupations are associated with the HNE.

- We further expect an association between parents’ learned STEM vs. non-STEM occupations and children’s numerical competencies.

- (2)

- We further expect a similar interrelation between parents’ current STEM vs. non-STEM occupation, with the families’ HNE as a mediator, and children’s numerical competencies.

- Here, we expect, similarly to H1a, an association between parents’ current STEM vs. non-STEM occupation and the HNE.

- Additionally, we also hypothesize an association for parents’ current STEM vs. non-STEM occupation and children’s numerical competencies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Children’s Numerical Competencies

2.2.2. Home Numeracy Environment

2.2.3. Parental Occupations and Their Allocation to STEM

2.3. Analytical Approach

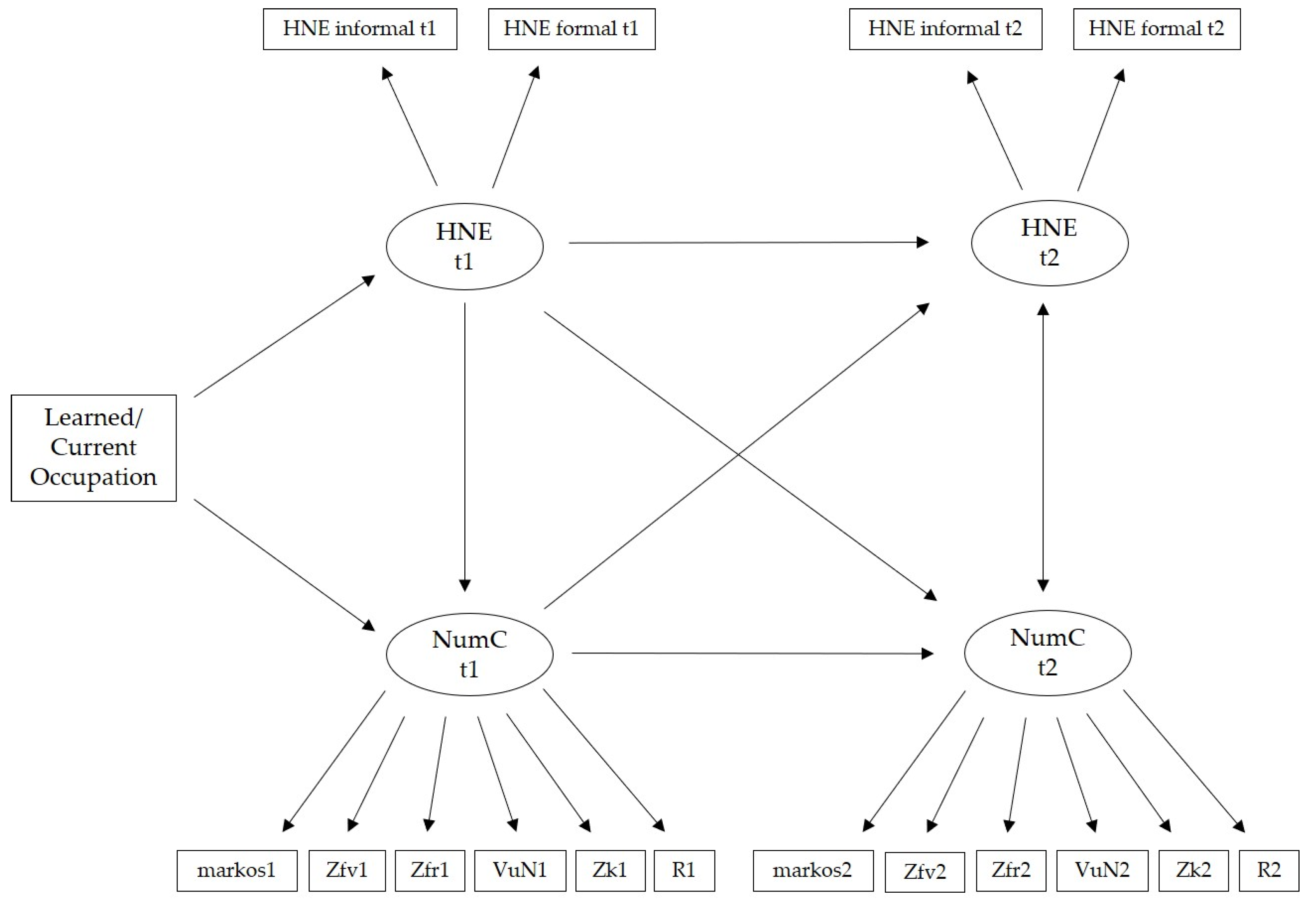

2.4. Measurement Model and Statistical Model Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Measurement Models of Numerical Competence and the HNE

3.2. Correlational Analyses

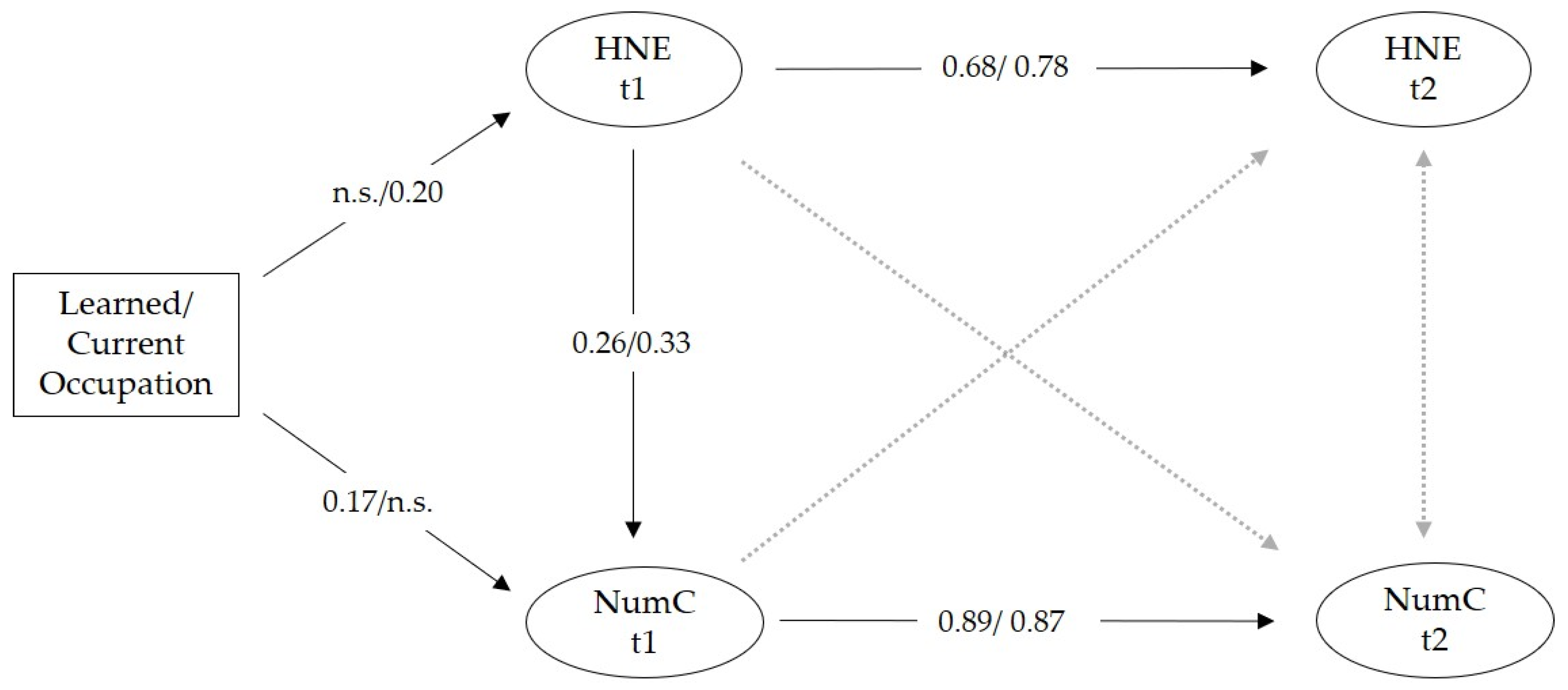

3.3. Statistical Models of Parental Occupation, HNE and Children’s Numerical Competencies

4. Discussion

4.1. Direct Links between Parents’ STEM Occupations and Children’s Numerical Competencies

4.2. Associations between Parents’ Characteristics and the Home Numeracy Environment

4.3. The Role of the Home Numeracy Environment in Children’s Numerical Competencies

4.4. Limitations and Further Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Items | Item Description |

| Item 1 | How often does your child count in everyday life (e.g., when setting the table with tableware or when counting down hours or days until a certain event)? |

| Item 2 | How often do you play counting games with your child (e.g., “Benjamin Blümchen: Lerne Zählen”, “Die Maus-Lern-Spiel-Sammlung”, “Kosmolino: 1,2,3…”)? |

| Item 3 | How often do you play arithmetic games with your child (e.g., “Ich lerne Rechnen”, “Zahlen und Rechnen”, “Zählen und Rechnen mit Ernie und Bert”, “1 + 2 = 3 Rechnen macht Spaß”)? |

| Item 4 | How often do you play dice games with your child (e.g., “Mensch ärgere Dich nicht”or “Tempo, kleine Schnecke”)? |

| Item 5 | How often do you involve your child in weighing and counting food and paying at the counter when you go shopping? |

| Item 6 | How often do you involve your child in counting, weighing, or measuring ingredients when cooking? |

| Item 7 | How often do you talk with your child about measurements (e.g., weight, temperature, or speed)? |

| Item 8 | In our family, we think that it is important to be able to calculate. |

| Item 9 | My child shows interest in learning to calculate and to count and is looking forward to it. |

| Item 10 | Mathematics is important in our family. |

References

- Elliott, L.; Bachman, H.J. SES disparities in early math abilities: The contributions of parents’ math cognitions, practices to support math, and math talk. Dev. Rev. 2018, 49, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, E.T.; Tamis-LeMonda, C.S. Trajectories of the home learning environment across the first 5 years: Associations with children’s vocabulary and literacy skills at prekindergarten. Child Dev. 2011, 82, 1058–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niklas, F.; Schneider, W. Home learning environment and development of child competencies from kindergarten until the end of elementary school. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 49, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajewski, K.; Schneider, W. Early development of quantity to number-word linkage as a precursor of mathematical school achievement and mathematical difficulties: Findings from a four-year longitudinal study. Learn. Instr. 2009, 19, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, G.J.; Dowsett, C.J.; Claessens, A.; Magnuson, K.; Huston, A.C.; Klebanov, P.; Pagani, L.S.; Feinstein, L.; Engel, M.; Brooks-Gunn, J.; et al. School readiness and later achievement. Dev. Psychol. 2007, 43, 1428–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bachman, H.J.; Votruba-Drzal, E.; El Nokali, N.E.; Castle Heatly, M. Opportunities for Learning Math in Elementary School. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2015, 52, 894–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susperreguy, M.I.; Jiménez Lira, C.; Xu, C.; LeFevre, J.-A.; Blanco Vega, H.; Benavides Pando, E.V.; Ornelas Contreras, M. Home Learning Environments of Children in Mexico in Relation to Socioeconomic Status. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 626159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, G.J.; Brooks-Gunn, J.; Klebanov, P.K. Economic Deprivation and Early Childhood Development. Child Dev. 1994, 65, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, E.S.C. Family influences on science learning among Hong Kong adolescents: What we learned from PISA. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2010, 8, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khundrakpam, B.; Choudhury, S.; Vainik, U.; Al-Sharif, N.; Bhutani, N.; Jeon, S.; Gold, I.; Evans, A. Distinct influence of parental occupation on cortical thickness and surface area in children and adolescents: Relation to self-esteem. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2020, 41, 5097–5113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, S.F.; Portilla, X.A. Recent Trends in Income, Racial, and Ethnic School Readiness Gaps at Kindergarten Entry. AERA Open 2016, 2, 2332858416657343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Starkey, P.; Klein, A.; Wakeley, A. Enhancing young children’s mathematical knowledge through a pre-kindergarten mathematics intervention. Early Child. Res. Q. 2004, 19, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, N.C.; Kaplan, D.; Locuniak, M.N.; Ramineni, C. Predicting First-Grade Math Achievement from Developmental Number Sense Trajectories. Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 2007, 22, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dearing, E.; Casey, B.M.; Ganley, C.M.; Tillinger, M.; Laski, E.; Montecillo, C. Young girls’ arithmetic and spatial skills: The distal and proximal roles of family socioeconomics and home learning experiences. Early Child. Res. Q. 2012, 27, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFlorio, L.; Beliakoff, A. Socioeconomic Status and Preschoolers’ Mathematical Knowledge: The Contribution of Home Activities and Parent Beliefs. Early Educ. Dev. 2015, 26, 319–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannelli, G.C.; Rapallini, C. Parental occupation and children’s school outcomes in math. Res. Econ. 2019, 73, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Plasman, J.; Gottfried, M.; Williams, D.; Ippolito, M.; Owens, A. Parents’ Occupations and Students’ Success in STEM Fields: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2021, 6, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoraka, M.; Arnold, R.; Kim, E.S.; Salinitri, G.; Kromrey, J. Parental Characteristics and the Achievement Gap in Mathematics: Hierarchical Linear Modeling Analysis of Longitudinal Study of American Youth (LSAY). Alta. J. Educ. Res. 2015, 61, 280–293. [Google Scholar]

- White, K.R. The relation between socioeconomic status and academic achievement. Psychol. Bull. 1982, 91, 461–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braveman, P.A.; Cubbin, C.; Egerter, S.; Chideya, S.; Marchi, K.S.; Metzler, M.; Posner, S. Socioeconomic status in health research: One size does not fit all. JAMA 2005, 294, 2879–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, M.J. The Neuroscience of Socioeconomic Status: Correlates, Causes, and Consequences. Neuron 2017, 96, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- OECD. PISA in Focus; OECD: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Omolade, A.; Kassim, A.; Modupe, S. Relative Effects of Parents’ Occupation, Qualification and Academic Motivation of Wards on Students’ Achievement in Senior Secondary School Mathematics in Ogun State. J. Educ. Pract. 2014, 5, 99–105. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, S.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhu, L. Associations among attitudes, perceived difficulty of learning science, gender, parents’ occupation and students’ scientific competencies. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2017, 39, 2171–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erola, J.; Jalonen, S.; Lehti, H. Parental education, class and income over early life course and children’s achievement. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 2016, 44, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lawson, K.M.; Crouter, A.C.; McHale, S.M. Links between Family Gender Socialization Experiences in Childhood and Gendered Occupational Attainment in Young Adulthood. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 90, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, J.; Marsh, H.W.; Parker, P.D.; Dicke, T.; van Zanden, B. Countries, parental occupation, and girls’ interest in science. Lancet 2019, 393, e6–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bowden, M.; Bartkowski, J.; Xu, X.; Lewis Jr., R. Parental Occupation and the Gender Math Gap: Examining the Social Reproduction of Academic Advantage among Elementary and Middle School Students. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bott, P.; Helmrich, R.; Zika, G. MINT-Berufe—die Not ist nicht so groß wie oft behauptet! Analysen aus der ersten BIBB-IAB Qualifikations- und Berufsfeldprojektion. In Indikatoren und Benchmarks; Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung: Bonn, Germany, 2010; pp. 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Niklas, F.; Wirth, A.; Guffler, S.; Drescher, N.; Ehmig, S.C. The Home Literacy Environment as a Mediator between Parental Attitudes toward Shared Reading and Children’s Linguistic Competencies. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burghardt, L.; Linberg, A.; Lehrl, S.; Konrad-Ristau, K. The relevance of the early years home and institutional learning environments for early mathematical competencies. J. Educ. Res. Online 2020, 12, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, Y.; Rossbach, H.-G.; Weinert, S.; Ebert, S.; Kuger, S.; Lehrl, S.; von Maurice, J. Home and preschool learning environments and their relations to the development of early numeracy skills. Early Child. Res. Q. 2012, 27, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 1979; ISBN 9780674224575. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 1980; ISBN 9780674076686. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, N.C.; Kaplan, D.; Nabors Oláh, L.; Locuniak, M.N. Number sense growth in kindergarten: A longitudinal investigation of children at risk for mathematics difficulties. Child Dev. 2006, 77, 153–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passolunghi, M.C.; Vercelloni, B.; Schadee, H. The precursors of mathematics learning: Working memory, phonological ability and numerical competence. Cogn. Dev. 2007, 22, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niklas, F.; Schneider, W. Casting the die before the die is cast: The importance of the home numeracy environment for preschool children. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2014, 29, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niklas, F.; Cohrssen, C.; Tayler, C. Improving Preschoolers’ Numerical Abilities by Enhancing the Home Numeracy Environment. Early Educ. Dev. 2016, 27, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeFevre, J.-A.; Skwarchuk, S.-L.; Smith-Chant, B.; Fast, L.; Kamawar, D.; Bisanz, J. Home Numeracy Experiences and Children´s Math performance in the Early School Years. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2009, 41, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohrssen, C.; Niklas, F. Using mathematics games in preschool settings to support the development of children’s numeracy skills. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 2019, 27, 322–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasteiger, H.; Moeller, K. Fostering early numerical competencies by playing conventional board games. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2021, 204, 105060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skwarchuk, S.-L.; Sowinski, C.; LeFevre, J.-A. Formal and informal home learning activities in relation to children’s early numeracy and literacy skills: The development of a home numeracy model. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2014, 121, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehrl, S.; Ebert, S.; Blaurock, S.; Rossbach, H.-G.; Weinert, S. Long-term and domain-specific relations between the early years home learning environment and students’ academic outcomes in secondary school. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2020, 31, 102–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxe, G.B.; Guberman, S.R.; Gearhart, M.; Gelman, R.; Massey, C.M.; Rogoff, B. Social Processes in Early Number Development. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 1987, 52, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajewski, K. Vorschulische Mengenbewusstheit von Zahlen und ihre Bedeutung für die Früherkennung von Rechenschwäche. [Preschool awareness of quantities and numbers and their importance for the early detection of arithmetic weaknesses]. In Diagnostik von Mathematikleistungen; Hasselhorn, M., Marx, H., Schneider, W., Eds.; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2005; pp. 49–70. ISBN 9783801718664. [Google Scholar]

- Sarama, J.; Clements, D.H. Early Childhood Mathematics Education Research: Learning Trajectories for Young Children; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 9781135592509. [Google Scholar]

- Kleemans, T.; Peeters, M.; Segers, E.; Verhoeven, L. Child and home predictors of early numeracy skills in kindergarten. Early Child. Res. Q. 2012, 27, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeFevre, J.-A.; Polyzoi, E.; Skwarchuk, S.-L.; Fast, L.; Sowinski, C. Do home numeracy and literacy practices of Greek and Canadian parents predict the numeracy skills of kindergarten children? Int. J. Early Years Educ. 2010, 18, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melhuish, E.; Phan, M.; Sylva, K.; Sammons, P.; Siraj-Blatchford, I.; Taggart, B. Effects of the Home Learning Environment and Preschool Center Experience upon Literacy and Numeracy Development in Early Primary School. J. Soc. Issues 2008, 64, 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niklas, F.; Annac, E.; Wirth, A. App-based learning for kindergarten children at home (Learning4Kids): Study protocol for cohort 1 and the kindergarten assessments. BMC Pediatr. 2020, 20, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehlert, A.; Ricken, G.; Fritz, A. MARKO-Screening—Mathematik- und Rechenkonzepte im Vorschulalter—Screening [MARKO-Screening—Mathematics and Concepts of Calculation before School Entry]; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Krajewski, K. MBK 0. Test Mathematischer Basiskompetenzen im Kindergartenalter [MBK 0. Assessment of Basic Mathematical Competencies in Kindergarten Age], 1st ed.; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Endlich, D.; Berger, N.; Küspert, P.; Lenhard, W.; Marx, P.; Weber, J.; Schneider, W. WVT: Würzburger Vorschultest: Erfassung Schriftsprachlicher und Mathematischer (Vorläufer-) Fertigkeiten und Sprachlicher Kompetenzen im Letzten Kindergartenjahr [WVT: Würzburg Preschool Test: Assessment of Literacy and Mathematical (Precursor) Abilities and Linguistic Competencies in the Last Year of Kindergarten]; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Niklas, F.; Cohrssen, C.; Tayler, C. Parents supporting learning: A non-intensive intervention supporting literacy and numeracy in the home learning environment. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 2016, 24, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundesagentur für Arbeit. Ingenieurberufe [Engineering Professions]. 2013. Available online: https://statistik.arbeitsagentur.de/DE/Statischer-Content/Grundlagen/Klassifikationen/Klassifikation-der-Berufe/KldB2010/Arbeitshilfen/Berufsaggregate/Generische-Publikationen/Steckbrief-Ingenieur.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=5 (accessed on 2 July 2021).

- Bundesagentur für Arbeit. MINT-Berufe [STEM-Occupations]. 2017. Available online: https://statistik.arbeitsagentur.de/DE/Statischer-Content/Grundlagen/Klassifikationen/Klassifikation-der-Berufe/KldB2010/Arbeitshilfen/Berufsaggregate/Generische-Publikationen/MINTBerufe.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=5 (accessed on 2 July 2021).

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen, L.K.; Muthen, B.O. MPlus User’s Guide: Eighth Edition; Muthen, L.K., Muthen, B.O., Eds.; Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.scirp.org/(S(czeh2tfqyw2orz553k1w0r45))/reference/ReferencesPapers.aspx?ReferenceID=2123077 (accessed on 2 July 2021).

- Lai, K. Estimating Standardized SEM Parameters Given Nonnormal Data and Incorrect Model: Methods and Comparison. Struct. Equ. Modeling Multidiscip. J. 2018, 25, 600–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacker, R.E.; Lomax, R.G. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling, 3th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 9781841698908. [Google Scholar]

- Susperreguy, M.I.; Douglas, H.; Xu, C.; Molina-Rojas, N.; LeFevre, J.-A. Expanding the Home Numeracy Model to Chilean children: Relations among parental expectations, attitudes, activities, and children’s mathematical outcomes. Early Child. Res. Q. 2020, 50, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornburg, C.B.; Borriello, G.A.; Kung, M.; Lin, J.; Litkowski, E.; Cosso, J.; Ellis, A.; King, Y.A.; Zippert, E.; Cabrera, N.J.; et al. Next directions in measurement of the home mathematics environment: An international and interdisciplinary perspective. J. Numer. Cogn. 2021, 7, 195–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Río, M.F.; Strasser, K.; Cvencek, D.; Susperreguy, M.I.; Meltzoff, A.N. Chilean kindergarten children’s beliefs about mathematics: Family matters. Dev. Psychol. 2019, 55, 687–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maple, S.A.; Stage, F.K. Influences on the Choice of Math/Science Major by Gender and Ethnicity. Am. Educ. Res. J. 1991, 28, 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.; Burrus, J. Predicting STEM Major and Career Intentions With the Theory of Planned Behavior. Career Dev. Q. 2019, 67, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missall, K.; Hojnoski, R.L.; Caskie, G.I.L.; Repasky, P. Home Numeracy Environments of Preschoolers: Examining Relations among Mathematical Activities, Parent Mathematical Beliefs, and Early Mathematical Skills. Early Educ. Dev. 2015, 26, 356–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tazouti, Y.; Malarde, A.; Michea, A. Parental beliefs concerning development and education, family educational practices and children’s intellectual and academic performances. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2010, 25, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viljaranta, J.; Lazarides, R.; Aunola, K.; Räikkönen, E.; Nurmi, J.-E. The Different Role of Mothers’ and Fathers’ Beliefs in the Development of Adolescents’ Mathematics and Literacy Task Values. Int. J. Gend. Sci. Technol. 2015, 7, 297–317. [Google Scholar]

- Siekmann, G.; Korbel, P. Defining “STEM” Skills: Review and Synthesis of the Literature.- support document 1NCVER, Adelaide. 2016. Available online: http://www.ncvre.edu.au (accessed on 2 July 2021).

- Steffensky, M. Naturwissenschaftliche Bildung in Kindertageseinrichtungen. [STEM Education in Early Childhood Institutions]; WiFF Expertisen; Deutsches Jugendinstitut e.V.: München, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Albarracín, D.; Wyer, R.S. The Cognitive Impact of Past Behavior: Influences on Beliefs, Attitudes, and Future Behavioral Decisions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uğraş, M. The Effects of STEM Activities on STEM Attitudes, Scientific Creativity and Motivation Beliefs of the Students and Their Views on STEM Education. IOJES 2018, 10, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenschein, S.; Galindo, C.; Metzger, S.R.; Thompson, J.A.; Huang, H.C.; Lewis, H. Parents’ Beliefs about Children’s Math Development and Children’s Participation in Math Activities. Child Dev. Res. 2012, 2012, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cech, E.A.; Blair-Loy, M. The changing career trajectories of new parents in STEM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 4182–4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Puglisi, M.L.; Hulme, C.; Hamilton, L.G.; Snowling, M.J. The Home Literacy Environment Is a Correlate, but Perhaps Not a Cause, of Variations in Children’s Language and Literacy Development. Sci. Stud. Read. 2017, 21, 498–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, S.K.; Dulay, K.M.; McBride, C. Parents’ characteristics, the home environment, and children’s numeracy skills: How are they related in low- to middle-income families in the Philippines? J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2020, 192, 104780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucker, T.A.; Montroy, J.; Master, A.; Assel, M.; McCallum, C.; Yeomans-Maldonado, G. Expectancy-value theory & preschool parental involvement in informal STEM learning. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2021, 76, 101320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.-T.; Degol, J.L. Gender Gap in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM): Current Knowledge, Implications for Practice, Policy, and Future Directions. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 29, 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaya, L.; Stafford, F.; Zamarro, G. Gender gaps in math performance, perceived mathematical ability and college STEM education: The role of parental occupation. Educ. Econ. 2021, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niepel, C.; Stadler, M.; Greiff, S. Seeing is believing: Gender diversity in STEM is related to mathematics self-concept. J. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 111, 1119–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Río, M.F.; Susperreguy, M.I.; Strasser, K.; Salinas, V. Distinct Influences of Mothers and Fathers on Kindergartners’ Numeracy Performance: The Role of Math Anxiety, Home Numeracy Practices, and Numeracy Expectations. Early Educ. Dev. 2017, 28, 939–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silinskas, G.; Di Lonardo, S.; Douglas, H.; Xu, C.; LeFevre, J.-A.; Garckija, R.; Gabrialaviciute, I.; Raiziene, S. Responsive home numeracy as children progress from kindergarten through Grade 1. Early Child. Res. Q. 2020, 53, 484–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía-Rodríguez, A.M.; Luyten, H.; Meelissen, M.R.M. Gender Differences in Mathematics Self-concept across the World: An Exploration of Student and Parent Data of TIMSS 2015. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2021, 19, 1229–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niklas, F.; Schneider, W. Die Anfänge geschlechtsspezifischer Leistungsunterschiede in mathematischen und schriftsprachlichen Kompetenzen. [The beginning of gender-based performance differences in mathematics and linguistic competencies]. Z. Für Entwickl. Und Pädagogische Psychol. 2012, 44, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | N | M | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HNE_t1 | 190 | 2.70 | 0.71 | 0.35 | 3.85 |

| HNE_t2 | 186 | 2.87 | 0.57 | 1.01 | 3.95 |

| NumC_t1 | 190 | 26.70 | 12.50 | 0.00 | 61.00 |

| NumC_t2 | 188 | 36.20 | 12.80 | 9.00 | 61.00 |

| Learned Occupation | 181 | 0.55 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Current Occupation | 164 | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0.00 | 1.00 |

| Χ2 | df | p | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numerical Competence t1 | 3.933 | 8 | 0.86 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Numerical Competence t2 | 10.578 | 8 | 0.22 | 0.99 | 0.04 | 0.01 |

| HNE formal t1 | 7.853 | 5 | 0.16 | 0.98 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| HNE formal t2 | 7.088 | 5 | 0.21 | 0.98 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| HNE informal t1 | 33.970 | 29 | 0.24 | 0.99 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| HNE informal t2 | 63.196 | 29 | 0.00 | 0.93 | 0.08 | 0.06 |

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learned Occupation | 0.508 ** | 0.171 * | 0.109 | 0.209 ** | 0.255 * |

| Current Occupation (2) | 1 | 0.183 * | 0.154 | 0.095 | 0.152 |

| HNE t1 (3) | 1 | 0.866 ** | 0.317 ** | 0.278 ** | |

| HNE t2 (4) | 1 | 0.333 ** | 0.321 ** | ||

| NumC t1 (5) | 1 | 0.895 ** | |||

| NumC t2 (6) | 1 |

| Χ2 | df | p | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learned Occupation | 188.310 | 102 | 0.00 | 0.95 | 0.07 | 0.05 |

| Current Occupation | 175.126 | 102 | 0.00 | 0.95 | 0.07 | 0.05 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mues, A.; Birtwistle, E.; Wirth, A.; Niklas, F. Parental (STEM) Occupations, the Home Numeracy Environment, and Kindergarten Children’s Numerical Competencies. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 819. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11120819

Mues A, Birtwistle E, Wirth A, Niklas F. Parental (STEM) Occupations, the Home Numeracy Environment, and Kindergarten Children’s Numerical Competencies. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(12):819. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11120819

Chicago/Turabian StyleMues, Anna, Efsun Birtwistle, Astrid Wirth, and Frank Niklas. 2021. "Parental (STEM) Occupations, the Home Numeracy Environment, and Kindergarten Children’s Numerical Competencies" Education Sciences 11, no. 12: 819. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11120819

APA StyleMues, A., Birtwistle, E., Wirth, A., & Niklas, F. (2021). Parental (STEM) Occupations, the Home Numeracy Environment, and Kindergarten Children’s Numerical Competencies. Education Sciences, 11(12), 819. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11120819