Understanding Different Approaches to ECE Pedagogy through Tensions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review on the Multiple Viewpoints of Pedagogy in ECE across the Nordic Countries

3. Study Research Questions

- What approaches of early childhood education pedagogy can be identified in literature?

- What kind of tensions can be identified from the early childhood education pedagogy definition in literature?

- What are the shared elements among the different pedagogical approaches in ECE literature?

4. Methods

5. Results

5.1. Pedagogy through Interaction

5.2. Pedagogy through Scaffolding

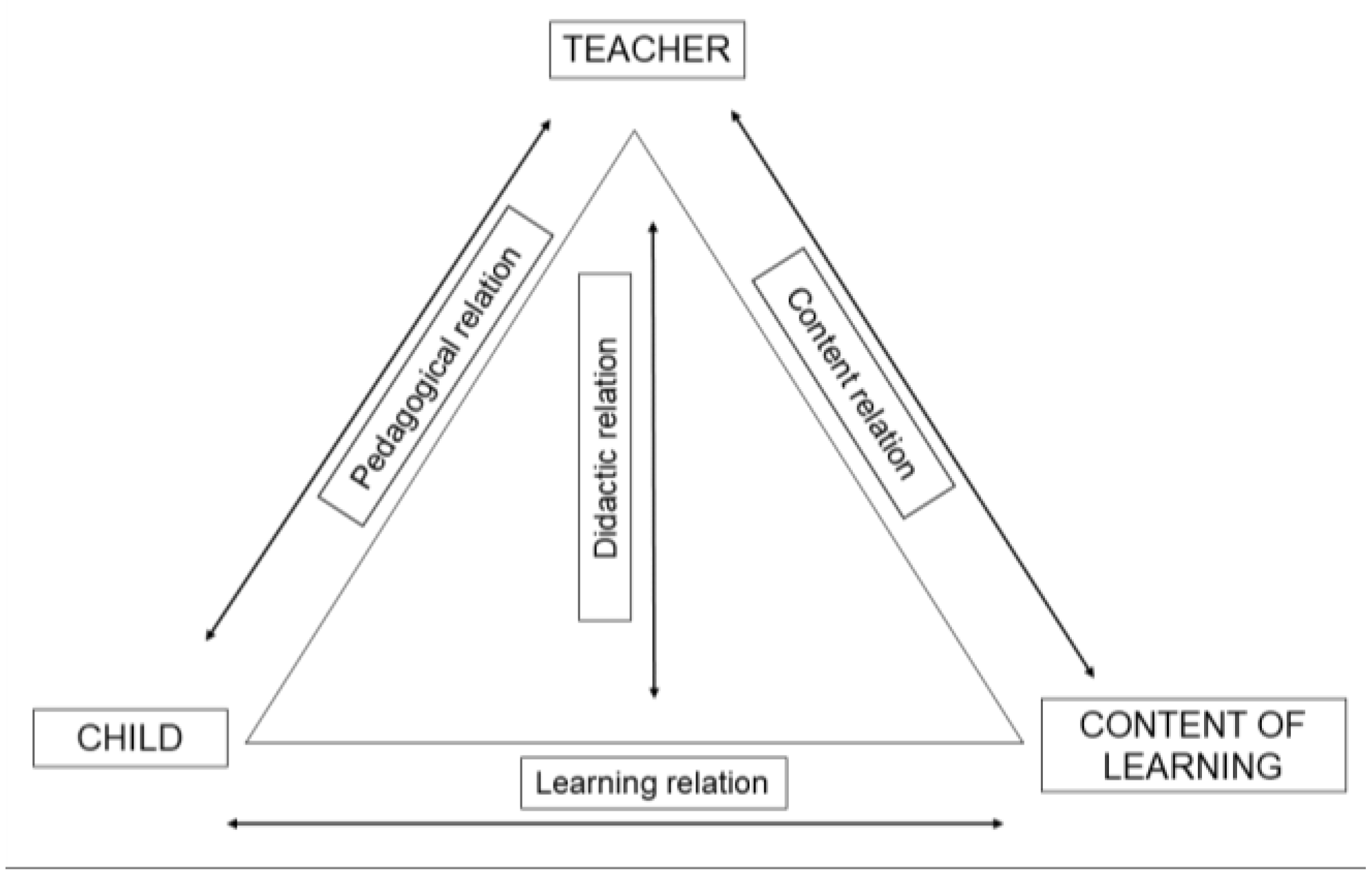

5.3. Pedagogy through Didactics

5.4. Pedagogy through Expertise

5.5. Pedagogy through Future Orientation

6. Discussion

7. Concluding Thoughts

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garvis, S.; Harju-Luukkainen, H.; Sheridan, S.; Williams, P. Nordic Families, Children and Early Childhood Education; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Garvis, S.; Ødegaard, E.E. Nordic Dialogues on Children and Families; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Harju-Luukkainen, H.; Kangas, J.; Garvis, S. Finnish Early Childhood Education and Care—A Multi-Theoretical Perspective on Research and Practice; Springer Nature AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bubikova-Moan, J.; Næss Hjetland, H.; Wollscheid, S. ECE Teachers’ views on play-based learning: A systematic review. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2019, 27, 776–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vallberg Roth, A.C. Nordic comparative analysis of guidelines for quality and content in early childhood education. Nord. Barnehageforskning 2014, 8, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sheridan, S.; Williams, P.; Sandberg, A. Systematic quality work in preschool. Int. J. Early Child. 2013, 45, 123–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, C.; Mortimore, P. Pedagogy: What do we know. In Understanding Pedagogy and Its Impact on Learning; Mortimore, P., Ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, P.; Boddy, J.; Cameron, C.; Heptinstall, E.; McQuail, S.; Simon, A.; Wigfall, V. Pedagogy-A Holistic, Personal Approach to Work with Children and Young People, Across Services 2008; Thomas Coram Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, J. Curriculum issues in national policy-making. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2005, 13, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangas, J.; Harju-Luukkainen, H.; Brotherus, A.; Gearon, L.; Kuusisto, A. Outlining Play and Playful Learning in Finland and Brazil: A Content Analysis of Early Childhood Education Policy Documents. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society—The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Leinonen, J.; Ojala, M.; Venninen, T. Children’s self-regulation in the context of participatory pedagogy in early childhood education. Early Educ. Dev. 2015, 26, 847–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangas, J.; Harju-Luukkainen, H.; Brotherus, A.; Kuusisto, A.; Gearon, L. Playing to Learn in Finland: Early childhood Curricular and Operational Context. In Policification of Early Childhood Education and Care: Early Childhood Education in the 21st Century; Garvis, S., Phillipson, S., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019; Volume III, pp. 71–85. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, E.; Brownlee, J.; Cobb-Moore, C.; Boulton-Lewis, G.; Walker, S.; Ailwood, J. Practices for teaching moral values in the early years: A call for a pedagogy of participation. Educ. Citizsh. Soc. Justice 2011, 6, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kansanen, P. The role of general education in teacher education. Z. Für Erzieh. 2004, 7, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsdottir, J.; Purola, A.-M.; Johansson, E.M.; Broström, S.; Emilson, A. Democracy, caring and competence: Values perspectives in ECEC curricula in the Nordic countries. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 2015, 23, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oers, B. Learning and learning theory from a cultural-historical point of view. In The transformation of Learning: Advances in Cultural-Historical Activity Theory; van Oers, B., Wardekker, W., Elbers, E., Van der Veer, R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Siraj-Blatchford, I.; Muttock, S.; Sylva, K.; Gilden, R.; Bell, D. Researching Effective Pedagogy in the Early Years; Institute of Education University of London Department of Educational Studies University of Oxford, Queens Printer: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Alila, K.; Ukkonen-Mikkola, T.; Kangas, J. Is there a ’Finnish methodology of teaching´—The pedagogical process in Finnish Early Childhood Education. In Finnish Early Childhood Education and Care—A Multi-Theoretical Perspective on Research and Practice; Harju-Luukkainen, H., Kangas, J., Garvis, S., Eds.; Springer Nature AG: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 219–232. [Google Scholar]

- Fleer, M. Early Learning and Development. Cultural-Historical Concepts in Play; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Harju-Luukkainen, H.; Kangas, J. The Role of Early Childhood Teachers in Finnish Policy Documents: Training Teachers for the Future. In International Perspectives on Early Childhood Teacher Education in the 21st Century; Boyd, W., Garvis, S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Kangas, J. Enhancing Children’s Participation in Early Childhood Education through Participatory Pedagogy. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pramling Samuelsson, I.; Asplund Carlsson, M. The playing learning child: Towards a pedagogy of early childhood. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2008, 52, 623–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyrhämä, R.; Maaranen, K. Research Orientation in a Teacher’s Work. In Miracle of Education: The Principles and Practices of Teaching and Learning in Finnish Schools, 2nd revised ed.; Niemi, H., Toom, A., Kallioniemi, A., Eds.; Sense publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Corsaro, W.A. The Sociology of Childhood, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kangas, J.; Reunamo, J. Action Telling method: From storytelling to crafting the future. In Story in Children’s Lives: Contributions of the Narrative Mode to Early Childhood Development, Literacy, and Learning; Kerry-Moran, K.J., Aerila, J.-A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zierer, K. Educational expertise: The concept of ‘mind frames’ as an integrative model for professionalisation in teaching. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2015, 41, 782–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, J.; Toom, A.; Leijen, Ä.; Husu, J.; Knezic, D.; Heikonen, L.; Tiilikainen, M.; García, M.; Allas, R.; Pedaste, M.; et al. Handbook on Teaching—Teachers’ Strategies in Classroom: A Student-Teaching Collection of Cases from Four European Countries; (DDOMI. Monografías del Departamento de Didáctica, Organización y Métodos de Investigación); University of Salamanca: Salamanca, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Harju-Luukkainen, H.; Garvis, S.; Kangas, J. “After Lunch We Offer Quiet Time and Meditation”: Early Learning Environments in Australia and Finland through the Lenses of Educators. In Globalization, Transformation, and Cultures in Early Childhood Education and Care: Reconceptualization and Comparison; Faas, S., Kasüschke, D., Nitecki, E., Urban, M., Wasmuth, H., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2019; pp. 203–219. [Google Scholar]

- Weckström, E.; Karlsson, L.; Pöllänen, S.; Lastikka, A.-L. Creating a Culture of Participation: Early Childhood Education and Care Educators in the Face of Change. Child. Soc. 2020, 35, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pursi, A.; Lipponen, L. Constituting play connection with very young children: Adults’ active participation in play. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 2018, 17, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alila, K.; Ukkonen-Mikkola, T. Käsiteanalyysistä varhaiskasvatuksen pedagogiikan määrittelyyn. Kasv. Suom. Kasv. Aikakauskirja 2018, 49, 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Punch, K.F.; Oancea, A. Introduction to Research Methods in Education; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torraco, R.J. Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2005, 4, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leedy, P.D.; Ormrod, J.E. Practical Research: Planning and Design; Merrill Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, R.; McIntyre, C.; Curr, V. The performing arts in ECE. Educ. Young Child. Learn. Teach. Early Child. Years 2017, 23, 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta, R.C.; Hamre, B.K.; Nguyen, T. Measuring and improving quality in early care and education. Early Child. Res. Q. 2020, 51, 285–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repo, L.; Sajaniemi, N. Prevention of bullying in early educational settings: Pedagogical and organisational factors related to bullying. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2015, 23, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranta, S.; Uusiautti, S.; Hyvärinen, S. The implementation of positive pedagogy in Finnish early childhood education and care: A quantitative survey of its practical elements. Early Child Dev. Care 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lager, K. Systematic Quality Work in a Swedish Context. In Nordic Families, Children and Early Childhood Education; Garvis, S., Harju-Luukkainen, H., Sheridan, S., Williams, P., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2019; pp. 173–192. [Google Scholar]

- Lembrér, D.; Johansson, M.C. Swedish preschool teachers’ views of children’s socialisation. In Proceedings of the 13th International Congress on Mathematical Education, Hamburg, Germany, 24–31 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kumpulainen, K.; Krokfors, L.; Lipponen, L.; Tissari, V.; Hilppö, J.; Rajala, A. Learning Bridges—Toward Participatory Learning Environments; CICERO Learning, Helsingin Yliopisto: Helsinki, Finland, 2010; Available online: http://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10138/15628 (accessed on 19 May 2021).

- Sheridan, S.; Williams, P.; Sandberg, A.; Vuorinen, T. Preschool teaching in Sweden—a profession in change. Educ. Res. 2011, 53, 415–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puntambekar, S.; Hübscher, R. Tools for scaffolding students in a complex learning environment: What have we gained and what have we missed? Educ. Psychol. 2005, 40, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Pol, J.; Volman, M.; Beishuizen, J. Scaffolding in teacher–student Interaction: A decade of research. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 22, 271–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kajamies, A.; Lepola, J.; Mattinen, A. Scaffolding Children’s Narrative Comprehension Skills in Early Education and Home Settings. In Story in Children’s Lives: Contributions of the Narrative Mode to Early Childhood Development, Literacy, and Learning; Kerry-Moran, K.J., Aerila, J.-A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 153–173. [Google Scholar]

- Hakkarainen, P.; Bredikyte, M. The zone of proximal development in play and learning. Cult.-Hist. Psychol. 2008, 4, 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Pramling, N.; Pramling Samuelsson, I. Educational Encounters: Nordic Studies in Early Childhood Didactics; Springer: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brostrøm, S.; Veijleskov, H. Didaktik i Børnehaven. Planer, Principer og Praksis [Didactics in Preschool: Plans, Principles and Practice; in Danish]; Dofolo: Fredrikshavn, Denmark, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Convention on the Rights of the Child. Treaty No. 27531. United Nations Treaty Series, 1577, 1989, pp. 3–178. Available online: https://treaties.un.org/doc/Treaties/1990/09/19900902%2003-14%20AM/Ch_IV_11p.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Bodrova, E. Make-believe play versus academic skills: A Vygotskian approach to today’s dilemma of early childhood education. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2008, 16, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunn Browlee, J.; Schraw, G.; Walker, S.; Ryan, M. Changes in preservice teachers’ personal epistemologies. In Handbook of Epistemic Cognition; Greene, J., Sandoval, B., Braten, I., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 300–325. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, K.; Cooper, J.M. Those Who Can, Teach; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, L.; Kinos, J.; Barbour, N.; Pukk, M.; Rosqvist, L. Child-initiated pedagogies in Finland, Estonia and England: Exploring young children’s views on decisions. Early Child Dev. Care 2015, 185, 1815–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stipek, D.J.; Byler, P. Early Childhood Teachers: Do They Practice What they Preach? Early Child. Res. Q. 1997, 12, 305–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukkonen-Mikkola, T.; Fonsén, E. Researching Finnish Early Childhood Teachers’ Pedagogical Work Using Layder’s Research Map. Australas. J. Early Child. 2018, 43, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A. Being an Expert Professional Practitioner: The Relational Turn in Expertise; Springer: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kinos, J. Professionalism—A Breeding ground for struggle. Finnish day care centre as an example. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2008, 16, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Directorate for Education and Skills. In The Future of Education and Skills; Education 2030; OECD: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schöning, M.; Witcomb, C. This Is the One Skill Your Child Needs for the Jobs of the Future; World Economic Forum: Education. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/09/skills-children-need-work-future-play-lego/ (accessed on 2 October 2018).

- Kangas, J.; Harju-Luukkainen, H. What is the future of ECE teacher profession? Teacher’s agency in Finland through the lenses of policy documents. Morning Watch. Educ. Soc. Anal. 2021, 49, 48–75. [Google Scholar]

- Sairanen, H.; Kangas, J.; Sintonen, S. Finnish teachers making sense of and promoting multiliteracies in early years education. In Multiliteracies and Early Years Innovation; Kumpulainen, K., Sefton-Green, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 42–60. [Google Scholar]

- Maaranen, K.; Kynäslahti, H.; Byman, R.; Jyrhämä, R.; Sintonen, S. Teacher Education Matters: Finnish Teacher Educators’ Concerns, Beliefs, and Values. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2018, 42, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, N. Children, Family and the State. Decision-Making and Child Participation; The Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kuusisto, A.; Poulter, S.; Harju-Luukkainen, H. Worldviews and National Values in Swedish, Norwegian and Finnish Early Childhood Education and Care Curricula. Int. Res. Early Child. Educ. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Atjonen, P. Tulevaisuuden pedagogiikka. Kuuminta HOTtia etsimässä? Available online: https://docplayer.fi/37086075-Tulevaisuuden-pedagogiikka.html (accessed on 30 November 2021).

| Thematic Approach to Pedagogy | Keywords Describing the Approach |

|---|---|

| Pedagogy through interaction | Care, sensitivity toward the child, belonging, interaction, personal well-being, sense of security, safety, care |

| Pedagogy through scaffolding | Support to expand learning, children’s agency, co-operation, zone of proximal development, participation, shared meaning-making |

| Pedagogy through didactics | Subject orientation and management, curriculum, traditional teaching, self-regulation, cognitive learning |

| Pedagogy through expertise | Profession, knowledge, know-how, competence, skills, methods |

| Pedagogy through future orientation | Curriculum, goals of education, sustainable education, future teachers, innovations, transversal competencies |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kangas, J.; Ukkonen-Mikkola, T.; Harju-Luukkainen, H.; Ranta, S.; Chydenius, H.; Lahdenperä, J.; Neitola, M.; Kinos, J.; Sajaniemi, N.; Ruokonen, I. Understanding Different Approaches to ECE Pedagogy through Tensions. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 790. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11120790

Kangas J, Ukkonen-Mikkola T, Harju-Luukkainen H, Ranta S, Chydenius H, Lahdenperä J, Neitola M, Kinos J, Sajaniemi N, Ruokonen I. Understanding Different Approaches to ECE Pedagogy through Tensions. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(12):790. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11120790

Chicago/Turabian StyleKangas, Jonna, Tuulikki Ukkonen-Mikkola, Heidi Harju-Luukkainen, Samuli Ranta, Heidi Chydenius, Jaana Lahdenperä, Marita Neitola, Jarmo Kinos, Nina Sajaniemi, and Inkeri Ruokonen. 2021. "Understanding Different Approaches to ECE Pedagogy through Tensions" Education Sciences 11, no. 12: 790. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11120790

APA StyleKangas, J., Ukkonen-Mikkola, T., Harju-Luukkainen, H., Ranta, S., Chydenius, H., Lahdenperä, J., Neitola, M., Kinos, J., Sajaniemi, N., & Ruokonen, I. (2021). Understanding Different Approaches to ECE Pedagogy through Tensions. Education Sciences, 11(12), 790. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11120790