“I Thought It Was My Fault Just for Being Born”. A Review of an SEL Programme for Teenage Victims of Domestic Violence

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background to Silence, Prevalence and ACEs

1.2. Context for Research

1.3. Research Focus

- How can a specially tailored SEL programme positively affect social-emotional skills in 12–14-year-olds impacted by domestic violence?

- How can such a group help participants to develop an awareness of how domestic violence in their families affects their SEL skills?

- How can a small-scale programme generate themes, ideas and instruments to develop SEL programmes for other young people affected by domestic violence? [22] (p. 9).

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Preliminary Investigations

2.2. Ethical Approval

2.3. Designing the Programme

- Definition of the problem: the effects of domestic violence on teenage SEL

- Factors receptive to change: enhanced levels of SEL skills in participants

- Mechanism of change: interactive SEL peer group

- Delivered by means of a structured group SEL skills programme

2.4. Recruitment

2.5. The Process of the Programme ‘up2talk’

2.6. Approaches to Weekly Sessions ‘up2talk’

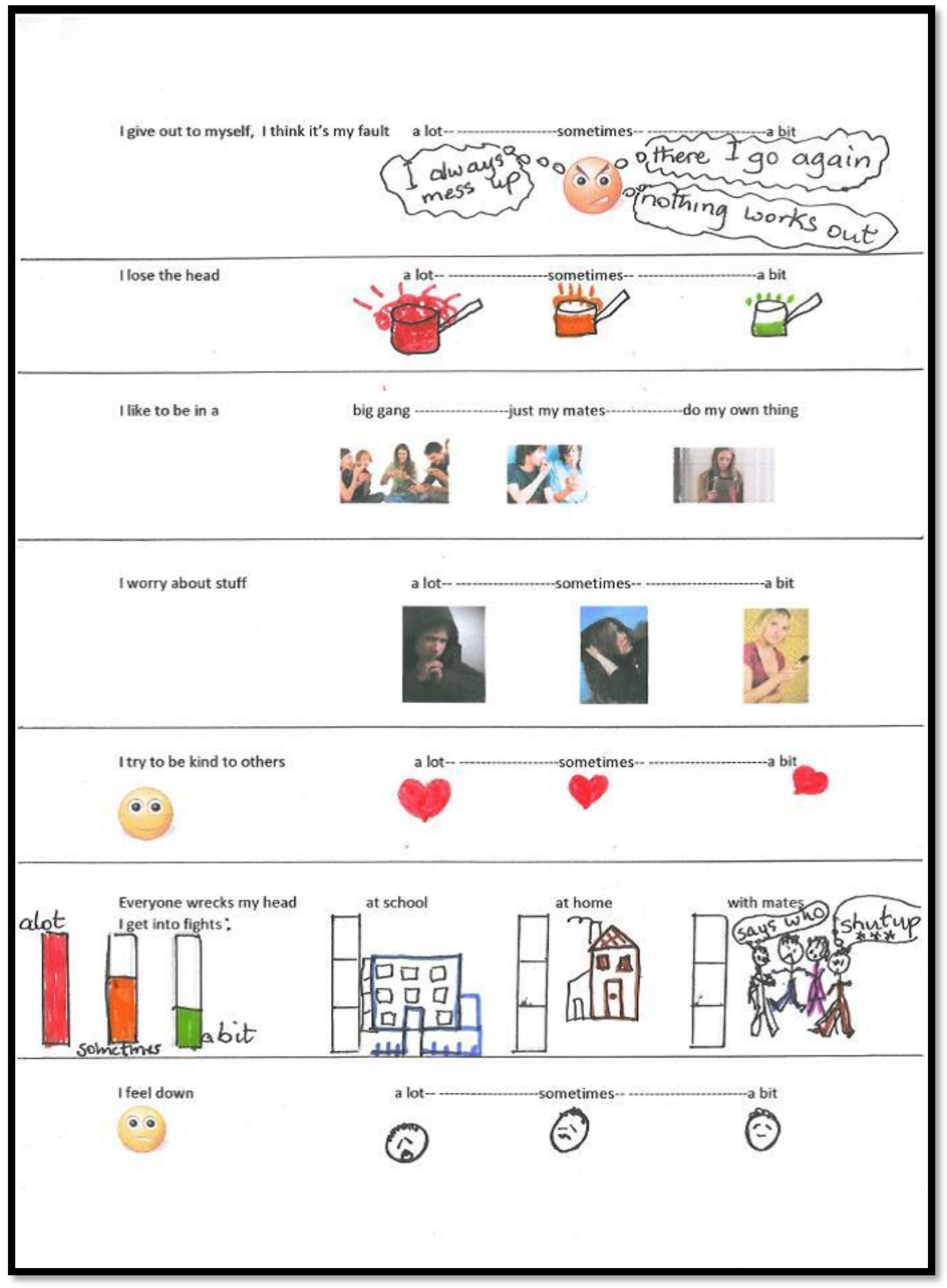

2.7. Instruments

2.8. Individual Interviews—Parents and Young People

2.9. Young People Interviewed Each Other, the Facilitator and Parents

2.10. Group Review for Parents Mid-Point, and Young People—Ongoing

2.11. Assertiveness Cartoons, Games and Activities

| A friend asks you to lend them money, you can’t do it, and they pressurize you by saying…. | A little boy on your road is stealing a lot in the shop, his mum works very hard and doesn’t know, his sister asks you to keep the secret. | Your friends are going to …? IT’S TROUBLE you don’t really want to and you will get in loads of hassle but they are all going? | A school mate calls your family names and says mean stuff about them. You hear about it AND… |

2.12. Drama and Filming Vignettes Written by the Group

2.13. Group Games, Discussions

2.14. Walking Debates

- “should we have to wear school uniforms?”

- “what makes a happy family?” “Would you accept a gay sibling in your family?”

Team Building

2.15. Emotional Literacy

2.16. Art and Clay—Individual and Group Expressions

2.17. Empathy with Others’ Feelings

Debates—Relationship with Fathers (in this Group, Fathers Were the Absent Abusive Parents)

2.18. Releasing Feelings through Pouring Water, and Painting over Old Feelings with New Hopes

2.19. Celebration Day

3. Findings/Results

3.1. Data Analysis

3.2. Triangulation of the Data

3.3. Central Themes of the Findings

3.4. Silence

“I don’t really remember, a lot happened outside the house”(Linda: ssitv 3)

“I don’t know, I just never really … dunno … didn’t talk about it.”(Jack: ssitv 3)

“upsetting the kids, bringing it all up again, just when we are settled”(Ruth: ssitv 2)

“I don’t know why I never talked about it (in therapy), I thought they were over it, didn’t want to drag it up again. I’ve never really gone into the ins and outs and talked properly. I either think, well he doesn’t remember, or it might affect him if I bring it up.”(Sara: ssitv. 2) [22] (pp. 197–198)

3.5. Self-Blame

“I didn’t know what my mam and dad were arguing about so I would have thought … is it because of me? Something I did …?”(Linda: ssitv 2) [22] (p. 220)

“You wonder if it’s your fault, like for being born?”(Jamie: ssitv 2) [22] (p. 219)

Researcher: Do you think maybe one of the reasons you take it (negative behaviour from children) is because you feel guilty?Mother: Yeah, because it was going on for a long time, and was very hard on the kids, but I didn’t see that for a long time.Researcher: So you feel guilty you didn’t do it early enough. However, you were hoping one day he would get better?Mother: I did, I think I got blinded by that, one day he will get better.(Betty: mother ssitv) [22] (p. 220)

3.6. Relationship with Father

“she (the child, Amanda) can’t put a gun up to her Dad’s head and tell him stop, can she?”(group debate after ‘Amanda’s story’ of violence) [22] (p. 218)

“He’ll (son) say you’re always giving Dad a hard time but my view is that no, when he’s with you he should be sober, but he seems to be very loyal to his dad in a way, even though he (Dad) doesn’t do a lot for him, or when he’s with him, he’s bored a lot of the time.”(Sara: ssitv 2) [22] (p. 238)

“you probably think it’s hypocritical after what he did; but he really helped me”,

“he’s just always there for me.”

“we tried but it all kicked off.”(ssitv 2) [22] (p. 238)

3.7. The Ability to Regulate Disclosure by Participants

Researcher: So, are you OK with talking more directly about the domestic violence now we know each other better?Dylan: Yeah …Researcher: If it’s too nosey like, would you tell me to stop?Dylan: Yeah, sure, assertiveness and all that!(ssitv 2) [22] (p. 227)

Researcher: Additionally, when we did the clay pots, did you feel it was a bit too serious when we asked people about effects of violence and things like that?Linda: No, if it was a bit too serious, we would have said that we didn’t like it.Researcher: OK, that’s good. Additionally, do you think all the group could have said ‘oh no, I don’t like that’ or just you?Linda: I don’t know about the rest of them. I just know I could have said out straight, it’s making me feel uncomfortable or whatever.(Linda: ssitv 2)

Researcher: Now that we have worked together and know each other, do you think you would be comfortable to talk more personally with me about the effects of living with domestic violence? If you find it too nosey or you want to change the subject … It’s up to you, same as always.Jamie: Well … I just call that a nuisance … it just went right over my head (makes a sweeping gesture over his head with his hand and pauses) (silence).Researcher: Ok. So, would you like to review the feelings chart and the other things we did?Jamie: Yeah …(ssitv 2) [22] (pp. 227–228)

3.8. Improved Family Relationships

When I came in from work yesterday, he gave me a hug, which is now—that’s not very unusual, but he is doing it more frequently now.(Ruth: ssitv 2)

“thank you for taking care of me all these years.”(Mother 3: ssitv 2)

“we are having a laugh again”,(Liz)

“we are closer, I thought that was gone for good.”(Sara) [22] (pp. 238,239)

3.9. Review of the Findings in Relation to the Research Questions

- How can a specially tailored SEL programme positively affect social-emotional skills in 12–14-year-olds impacted by domestic violence?

- How can such a group help participants to develop an awareness of how domestic violence in their families affects their SEL skills?

- How can a small-scale programme generate themes, ideas and instruments to develop SEL programmes for other young people affected by domestic violence? [22] (p. 9).

3.10. Social Skills—Positive Effects for Participants

Researcher: He had said, and you had said from the start that what you would like to see for him is more confidence. Do you see any changes in that department?Liz: All the different friends coming to the house, going to more sleepovers … a different variety of people he’s interacting with … he’s more confident … in front of everyone, in front of the class … People he knows, before he would have been nervous …(ssitv 2)

Researcher: What did you think was the best part of this for your child?Angie: Definitely the confidence, I see a big change that way. She’s definitely more settled and outgoing (celebration day).

“yeah, used to be always hanging around me, now it’s: ‘I’m off’”(Betty: ssitv 2) [22] (p. 237)

3.11. New Goals Regarding Commitment to School

Participant 1: Well, I don’t know if the course helped me but I’ve started putting my head down in school a lot more.Researcher: Yeah?Participant 1: 100% a lot more, and I find myself in less trouble … like they are speaking to me, like how good I’m doing and that I should get A grades in exams.(ssitv 3) [22] (p. 204)

3.12. Assertiveness Was Put into Action

Participant 4: I know one thing that’s changed. Assertiveness, when the computer game was broken, well I just said, like real calmly, no, it was broken when I got it … That’s not right! And they gave me the money back.(partcpt 4: ssitv 2.) [22] (p. 235)

3.13. Luke (Co-Facilitator) Review

Luke: Yeah, definitely the acting and the role playing of different situations, whether it be in the home or whether it be damaging situations in life; it was brilliant them being able to voice thoughts, feelings; challenge, develop their own life skills, build them as people, you know.[22] (p. 233)

3.14. Developing Listening Skills and Expressing Opinions

“well, I wouldn’t stop anyone but I wouldn’t like it in my own family”,

“you would have to stand up for your family”(walking debate) [22] (p. 211)

“Some people didn’t like to do acting but everyone wanted to do it in the end, it was fun.”(p. 226)

3.15. Emotional Literacy: Positive Effects for Participants

Loved the clay … it was very inspiring looking at what everyone else was doing and calling their pieces. You could just tell that it made sense. Like the spine of anger—I get a shiver in my spine when I’m angry.(partcpt 2: ssitv 2) [22] (p. 216).

3.16. Naming the Issue

Dylan: No, I don’t know … I never … actually had a name for itResearcher: Would you have ever talked to anyone?Dylan: Shakes his head.Researcher: So … be like a big secret?Dylan: Yeah.(Dylan: ssitv 2) [22] (p. 198)

3.17. Expressing Emotions

3.18. Awareness of Domestic Violence Effects on SEL

Researcher: How do you think that could affect how you behave at school?Jack: Being really bold.Researcher: Additionally, your work?Jack: Either good, expressing it through art or just being really … not want to do anything and be really upset in school.(ssitv 2)

3.19. Enhanced Self-Esteem

“tell someone you really trust, like family”

“just talk to someone.”(ssitv 2) [22] (p. 215)

Empathy

Researcher: So they could be a bit nervous about relationships, you mean?Jack: Yeah, and they could maybe feel a bit guilty, is it happening to anyone else that I don’t know about?(ssitv 2) [22] (p. 219)

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Øverlien, C.; Holt, S. European Research on Children, Adolescents and Domestic Violence: Impact, Interventions and Innovations. J. Fam. Violence 2019, 34, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO; LSHTM; SAMRA. Global and Regional Estimates of Violence Against Women: Prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-Partner Sexual Violence; UNICEF: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- Shannon, G. Audit of the Exercise by An Garda Síochána of the Provisions of Section 12 of the Child Care Act 1991; An Garda Síochána: Dublin, Ireland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D.; Parsons, S. Domestic Abuse of Women and Men in Ireland: Report on the National Study of Domestic Abuse; National Crime Council: Dublin, Ireland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, L.; Corral, S.; Bradley, C.; Fisher, H.L. The prevalence and impact of child maltreatment and other types of victimization in the UK: Findings from a population survey of caregivers, children and young people and young adults. Child Abuse Negl. 2013, 37, 801–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edleson, J. Overlap between child maltreatment and woman battering. Violence Against Women 1999, 5, 134–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellis, M.A.; Ashton, K.; Hughes, K.; Ford, K.; Bishop, J.; Paranjothy, S. Welsh Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE); Public Health Wales: Cardiff, Wales; Centre for Public Health: Liverpool, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Anda, R.F.; Felitti, V.J.; Bremner, J.D.; Walker, J.D.; Whitfield, C.; Perry, B.D.; Dube, S.R.; Giles, W.H. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 256, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, M. A Profile of Learners in Youthreach: Research Study Report; National Educational Psychological Service: Dublin, Ireland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Devaney, J. Chronic child abuse and domestic violence: Children and families with long-term and complex needs. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2008, 13, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, H.; Holt, S.; Whelan, S. Listen to Me! Children’s Experience of Domestic Violence; Trinity College: Dublin, Ireland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, S.; Buckley, H.; Whelan, S. The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: A review of the literature. Child Abuse Negl. 2008, 32, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. Behind Closed Doors; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Moylan, C.; Herrenkohl, T.; Sousa, C.; Tajima, E.; Herrenkohl, R.; Russo, M. The effects of child abuse and exposure to domestic violence on adolescent internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. J. Fam. Violence 2010, 25, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Collaborative for Academic Social and Emotional Learning. What Is Social and Emotional Learning. Available online: www.casel.org (accessed on 26 May 2015).

- Stanley, N. Children Experiencing Domestic Violence: A Research Review; Research in Practice: Dartington, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cater, Å.; Øverlien, C. Children exposed to domestic violence: A discussion about research ethics and researchers’ responsibilities. Nord. Soc. Work. Res. 2014, 4, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, M.; Lecky, Y.; O’Connor, S.; McMahon, K. Evaluation of the TLC Kidz Programme for Children and Mothers Recovering from Domestic Abuse; Barnardos: Dublin, Ireland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Houghton, C.; Youth Advisors. Justice Committee: Domestic Abuse (Scotland) Bill: Written Submission from the IMPACT Project-Young Survivors; Edinburgh University: Edinburgh, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q. Review Essay: Craig, D.V. (2009). Action research essentials (1st Ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Pp.248. Can. J. Action Res. 2012, 13, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, H. (Ed.) The Sage Handbook of Action Research, 3rd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sweetman, N. A Culture of Silence—A Study of a Social Emotional Learning (SEL) Intervention for Teenagers Affected by Domestic Violence. Ph.D. Thesis, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk, B.A. The developmental impact of childhood trauma. In Understanding Trauma: Integrating Biological, Clinical, and Cultural Perspectives; Kirmayer, L.J., Lemelson, R., Barad, M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lundy, L. ‘Voice’ is not enough: Conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2007, 33, 927–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Featherstone, B.; White, S.; Morris, K. Re-Imagining Child Protection: Towards Humane Social Work with Families; Policy Press, University of Bristol: Bristol, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wight, D.; Wimbush, E.; Jepson, R.; Doi, L. Six steps in quality intervention development (6SQuID). J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2016, 70, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Coburn, A.; Gormally, S. ‘They know what you are going through’: A service response to young people who have experienced the impact of domestic abuse. J. Youth Stud. 2014, 17, 642–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øverlien, C.; Hydén, M. Children’s actions when experiencing domestic violence. Childhood 2009, 16, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Theron, L.C.; Mitchell, C.; Stuart, J.; Smith, A. (Eds.) Picturing Research: Drawings as Visual Methodology; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R. Qualitative Research: Studying How Things Work; Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hutton, B. Scale of violence against Irish children hidden, claims EU: Report says 3500 child sexual abuse cases should be investigated or prosecuted a year. In The Irish Times; The Irish Times: Dublin, Ireland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- FRA European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. Violence against Women: An EU-Wide Survey; European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights Luxembourg: Luxembourg, 2014; ISBN 978-92-9239-379-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Violence and Health; Krug, E.G., Dahlberg, L.L., Mercy, J.A., Zwi, A.B., Lozano, R., Eds.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Elliffe, R.; Holt, S.; Øverlien, C. Hiding and being hidden: The marginalisation of children’s participation in research and practice responses to domestic violence and abuse. Soc. Work. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2021, 22, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundy, L.; McEvoy, L.; Byrne, B. Working with young children as co-researchers: An approach informed by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Early Educ. Dev. 2011, 22, 714–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundy, L. Children’s rights and educational policy in Europe: The implementation of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2012, 38, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, L.; Lloyd, K. Developing a Rights-Based Measure of Children’s Participation Rights in School and in Their Communities; Queen’s University Belfast: Belfast, UK; University of Ulster: Ulster, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, A.; Wydall, S. From ‘rights to action’: Practitioners’ perceptions of the needs of children experiencing domestic violence. Child Fam. Soc. Work. 2015, 20, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodman, E.; Roche, S.; McArthur, M.; Moore, T. Child protection practitioners: Including children in decision making. Child Fam. Soc. Work. 2018, 23, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, E.; Belton, E.; Barnard, M.; Cotmore, R.; Taylor, J. Recovering from domestic abuse, strengthening the mother–child relationship: Mothers’ and children’s perspectives of a new intervention. Child Care Pract. 2013, 19, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarth, E.; Moore, T.H.M.; Shaw, A.R.G.; Welton, N.J.; Feder, G.S.; Hester, M.; MacMillan, H.L.; Stanley, N. The effectiveness of targeted interventions for children exposed to domestic violence: Measuring success in ways that matter to children, parents and professionals. Child Abus. Rev. 2015, 24, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cater, Å. Children’s descriptions of participation processes in interventions for children exposed to intimate partner violence. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work. J. 2014, 31, 455–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J.A.; Weissberg, R.P. The Impact of After-School Programs That Promote Personal and Social Skills; Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning: Chicago, IL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, M.T.; Domitrovich, C.E.; Weissberg, R.P.; Durlak, J.A. Social and Emotional Learning as a public health approach to education. Futur. Child. 2017, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, S. Life Skills Matter, Not Just Points; Office of the Minister for Children and Youth Affairs: Dublin, Ireland, 2010.

- O’Sullivan, C.; Moynihan, S.; Collins, B.; Hayes, G.; Titley, A. (Eds.) The Future of SPHE: Problems and Possibilities: Proceedings from SPHE Network Conference 29th September, 2012; SPHE Network; DICE: Dublin, Ireland, 2014.

- Durlak, J.A.; Weissberg, R.P.; Dymnicki, A.B.; Taylor, R.D.; Schellinger, K.B. The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school based universal interventions. Child Dev. 2011, 82, 405–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, J.E.M.; Alexander, J.H.; Sixsmith, J.; Fellin, L.C. Children’s experiences of domestic violence and abuse: Siblings’ accounts of relational coping. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2016, 21, 649–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jones, D.E.; Greenberg, M.; Crowley, M. Early social-emotional functioning and public health: The relationship between kindergarten social competence and future wellness. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 2283–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Council for Curriculum and Assessment. Social, Personal and Health Education Curriculum Framework for Senior Cycle: Report on Consultation; NCCA: Dublin, Ireland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cosc: The National Office for the Prevention of Domestic Sexual and Gender-based Violence. Awareness Raising of Domestic and Sexual Violence: A Survey of Post-Primary Schools in Ireland; Department of Justice and Equality: Dublin, Ireland, 2012.

| Interviews | Participants | Parents | Purpose | Approach | Time |

| Initial | Young people Individually w/ researcher | To explain the programme | ‘Feelings chart’ and follow up questions | Day 1 15 min. | |

| Initial | Young people Individually w/family worker | To explain the programme and take questions | Explain context-support of family centre | Day 1 15 min. | |

| Initial | Young person(5 duos) | Child parent researcher and family worker (5 duos) | To ensure clarity between family members and facilitators | Discussion of hopes for the programme | Day 1 15 min. |

| Initial | Individually with researcher | To build trust and answer queries | Parent filled ‘Feelings chart’ re. their view of their child | Day 1 15 min. | |

| Initial | Individually with family worker | To answer queries/explain support role of family centre | Day 1 15 min. | ||

| Interviews | Participants | Parents | Purpose | Approach | Time |

| Four-week review | Researcher and family worker | Three out of five mothers attended | To inform Parents + check for queries/ concerns. | Group review by mothers. Peer discussion. | Week 4 30 min. |

| Final week review | Each participant (5) had an individual interview with researcher | to explore changes in understanding and actions. Reflect on the programme process | To revisit the ‘Feelings Chart’. To review the programme from participant’s view | Wk. 12 20 min. | |

| Final week review | Four mothers had an individual interview with the researcher | to discuss observed changes in child’s understanding and actions. | To explore parent observations of the young person’s responses to the programme | Wk. 12 20 min. | |

| Follow up review—4 months | participants individual interview with the researcher. | to explore the long-term view of the programme. | Revisit the ‘Feelings Chart’. A discussion of effects observed. | Wk. 27 20 min. |

| Application Instrument | Method of Use Participants | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instrument | Application | Purpose | Activity | Participants |

| Group games | Practice social emotional skills weekly | Relax and bond. Build skills and confidence | Communication and listening games | Young people researcher + Family worker |

| Assertiveness cartoons | Introduce concept visually | Learn the skills in action | Cartoons and games about life situations | Young people |

| Drama | Developed from assertiveness games | Express issues and dilemmasof life | Young people wrote, acted and filmed short pieces | Young people researcher + Family worker |

| Visual charts of life issues | Express emotion/ideas visually | Develop Emotional literacy | Concept + materials supplied | Young people |

| Debates | Express + listen to opinions. Explore difference in key issues | Expand empathy and understanding | Walking debate. Place yourself on a spectrum of opinion in room | Young people |

| Clay pieces | Creating a clay piece for a chosen emotion | Name and represent an emotion | Each one selects an emotion card and creates in clay. | Young people |

| Cookery | Bond and enjoy. Teamwork | Provide lunch each week | Participants prepared lunch and snacks | Young people researcher + Family worker |

| Domestic violence story and response ‘Amanda’s story’ | Group listen to story. Express emotion by pouring water individually | Safe to express emotions and discuss at a remove. | Family worker reads. Participants listen and respond. Discuss | Young people researcher + Family worker |

| Instrument | Application | Purpose | Method of use | Participant |

| Celebration Day Event | Group prepare art work exhibit. Drama, song and video for families | Share success and display work to family | Participants design and deliver entire event. | Group (5) Families (5) Staff of centre (10) Facilitator and family worker |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sweetman, N. “I Thought It Was My Fault Just for Being Born”. A Review of an SEL Programme for Teenage Victims of Domestic Violence. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 784. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11120784

Sweetman N. “I Thought It Was My Fault Just for Being Born”. A Review of an SEL Programme for Teenage Victims of Domestic Violence. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(12):784. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11120784

Chicago/Turabian StyleSweetman, Norah. 2021. "“I Thought It Was My Fault Just for Being Born”. A Review of an SEL Programme for Teenage Victims of Domestic Violence" Education Sciences 11, no. 12: 784. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11120784

APA StyleSweetman, N. (2021). “I Thought It Was My Fault Just for Being Born”. A Review of an SEL Programme for Teenage Victims of Domestic Violence. Education Sciences, 11(12), 784. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11120784