Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has contributed to the accelerated spread of e-learning around the world. In e-learning, self-regulation becomes more relevant than ever. Reducing the influence of traditional features of the face-to-face learning environment and increasing the impact of the e-environment place high demands on students’ self-regulation. The author’s self-regulation e-learning model emphasizes the position of e-learning at the intersection of the electronic environment and the learning environment. We observe a collision of the concepts of these two environments. The Internet is a more common environment that provokes the use of unacceptable tools and hints, which is a logical consequence of such behavior to pass the test, and not to gain knowledge. Therefore, the most important thing is that students have their own goals and strategies, and use the large resources of the electronic environment for development, and not for cheating. The authors conducted a survey (N = 767), which showed that students rate their self-efficacy of online learning higher in the e-environment than in the offline learning environment. Self-regulation indicators are the highest in the field of environment, and the lowest when setting goals and in time management.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the existing trends of increasing the share of e-learning in education worldwide. First of all, the problem of technological support for fully online education has grown [1]. Students and teachers need fast and stable networks, online communication tools, and digital educational resources [2,3,4]. After solving the problems of creating, communicating, and providing technical support for e-courses, it became necessary to take into account the level of technical competence, the psychological aspects of online learning [5,6,7], and the peculiarities of learning in an electronic environment to the extent that fully e-education can completely replace conventional one [8].

At the same time, the discussion of the advantages and problems of e-learning in higher education for students has a long history. The most obvious comparison of grades between online and face-to-face learning does not show a significant difference [9,10,11,12], even sometimes there are better grades in the online environment [13]. Since different factors can influence grades, they cannot serve as a reliable basis for the comparison.

Among the factors that cause a cautious attitude to online learning, one of the most important is that the completion rates are about 8–20% lower than in traditional full-time courses [14,15,16,17,18]. The widely observed higher rates in favor of retention for face-to-face learning compared to online learning could be caused by the features of online learning itself or by characteristics of the students who sign up for online courses themselves [19,20]. In addition, higher rates of attrition are observed in online courses [21,22]. One of the main problems is students’ perception of isolation and lack of communication [16,23]. Online courses “can appear to be an impersonal exercise, which leads students to feel ‘eSolated’ from instructional staff” [24,25].

Thus, the quality of interaction between teachers and students is considered as one of the most important factors [26,27,28], which is associated with the involvement of students in their educational activities [29,30].

Researchers reveal different forms of engagement such as affective, behavioral, and cognitive [31,32]. In addition, it would be possible to take into account the academic participation, which refers to academic identification (for example, communication with teachers) and participation in learning (for example, time to complete tasks, rather than skipping classes) [33].

The lack of direct communication between students, teachers, and peers requires special characteristics. Online students should have so-called “self-traits”, that are connected with:

- -

- Self-determination (competency, autonomy, and relatedness) [34,35];

- -

- Self-regulation [36,37,38,39] that associated with planning, management, and control of the learning process [40];

- -

- Self-discipline [26];

- -

- Self-efficacy [41,42,43,44] that is associated with self-directed behavior and autonomy [45] or students’ confidence in their abilities to successfully fulfill educational requirements [46];

- -

- Emotional intelligence [47].

In addition, students must be familiar with information and communication technologies and satisfied with the program [48,49,50].

One of the main advantages of online learning is flexibility [51] but this requires good time management skills [52]. Rochester and Pradel found out that online students appreciate the flexibility in the course and convenient access to various types of educational materials, but they report some problems with understanding the course content [53].

Self-regulation is currently considered one of the factors associated with the educational process. At the same time, the widespread use of e-learning highlights the problem of self-regulation. It requires a new approach that takes into account the specifics of the digital environment.

This study aims to develop the self-regulated model for e-learning, taking into account the specifics of learning in a digital environment and evaluate the model based on empirical data. Within the framework of this study, the following tasks were set: To identify the key factors affecting self-regulation in modern conditions; to identify possible relationships and contradictions between the traditional components of self-regulation and those that are directly related to the online environment, to make a quantitative assessment of them on the basis of the empirical research; to identify interrelationships of key factors and to show the features of the influence of the electronic environment on self-regulated learning.

1.1. Self-Regulated Learning Model

Self-regulation is a core aspect of human functioning that helps facilitate the successful pursuit of personal goals [54], at the same time there is no simple and straightforward understanding of this multidimensional concept [55]. Historically, self-regulation in education was viewed from cognitive-behavioral [56] and cognitive-development perspectives [57]. Social cognitive researchers paid attention to social and motivational factors [58]. Self-regulation was viewed through the prism of metacognition [59,60]. Nowadays, the theory of self-regulation combines cognitive, motivational, social, and behavioral factors taking into account the cultural organizational, and contextual variables [61].

Zimmerman described self-regulation as the degree to which students “are metacognitively, motivationally, and behaviorally active participants in their own learning process” [62,63]. Self-regulation is a mode of volition in which learners form goals following their needs and preferences (self-determination) and flexibly resolving action-related conflicts oriented at self-maintenance [64]. Students use various cognitive, metacognitive, and self-regulating learning and resource management strategies as part of their learning behavior [65]. Self-regulated learning is flexible and adaptable, students tend to construct their own repertoire of strategies [66]. Pintrich notes that students actively create their meanings, goals, and strategies based on information available in the external environment, as well as in their minds [67].

Researchers reveal personal, environmental, and behavioral determinants of self-regulated learning [68]. Triadic model associates behavior with personal and environmental factors. Strategy use is shown as follows: from Person to Behavior and further to Environment. Feedback comes to Person from Behavior and Environment. In addition, it unites covert self-regulation, behavioural self-regulation, and environmental self-regulation. [62,69]. So self-regulation will be the degree of self-influence on the immediate learning environment and behavior [70]. It includes self-generated thoughts, feelings, and actions to achieve one’s learning goals [71].

In the next stage, motivational factors were added to the model, and above all self-efficacy. Zimmerman and Moylan [70] demonstrate a dynamic cyclical model of self-regulation. It includes the performance phase with self-control and self-observation; the self-reflection phase with self-judgment and self-reaction; and the forethought phase with task analysis and self-motivation beliefs. And self-motivation beliefs include self-efficacy, outcome expectations, task interest/value, and goal orientation [70].

Self-efficacy is often considered as the main factor that affects self-regulated learning. According to psychologist Albert Bandura, who originally proposed the concept, self-efficacy is a person’s belief in own capability to successfully perform specified tasks [58]. Zimmerman and Moyla point out that self-efficacy is a source of motivation that precedes efforts to learn and affects students’ preparation and their willingness to self-regulate their learning [70]. The empirical research show that self-efficacy is directly associated with self-regulated learning strategies [72,73], and both self-efficacy and self-regulated learning strategies contributed to the prediction of students’ proficiency [74,75,76].

Pintrich developed four phases-model of self-regulation. The phases are forethought, planning, and activation; monitoring; control; and reaction and reflection. Each of them has four different areas for regulation: cognition, motivation/affect, behavior, and context. The author gives a conceptualization of the goals of academic achievements that students can accept in a classroom environment and their role in constraining self-regulated learning [67].

Boekaerts’s self-regulation model divides the process into two parts: mastering students’ skills and well-being between which students could switch. The ability to prioritize goals and overcome obstacles determines the choosing path. This model connects students’ perceptions of the environment and different strategies of self-regulation. The model combines task-in-context, (meta) cognitive strategy use, and motivational beliefs, taking into account such factors as appraisal, assessment, affect, and learning intention [77]. Boekaerts and Rozendaal emphasize that learning environment influences cognition and feelings (self-efficacy, value, etc.) [78].

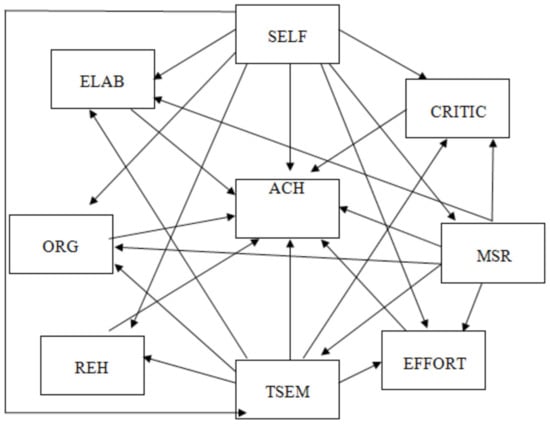

Most modern researchers do not single out self-regulation as an autonomous multicomponent phenomenon, but consider it among other factors affecting academic performance. For example, Sadi and Uyar offer the model that connects self-efficacy (SELF), rehearsal (REH), elaboration (ELAB), organization (ORG) and critical thinking strategies (CRITIC), metacognitive self-regulated learning strategies (MSR), time/study environmental management (TSEM), and effort regulation (EFFORT) with learning achievements (ACH) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Modeling of the relationship among self-efficacy (SE), rehearsal (REH), elaboration (ELAB), organization (ORG), critical thinking (CRITIC), metacognitive self-regulated learning strategies (MSR), time/study environmental management (TSEM), effort regulation (EFFORT), and achievement (ACH). Source Sadi and Uyar [72].

The structural model explains the relationship between self-efficacy in learning and academic performance, self-regulated learning strategies, and achievements of high school students. The results of the study show that factors such as metacognitive self-regulating learning strategies, self-efficacy in learning and productivity, organizational strategies, time/study management and effort regulation have a significant positive impact on academic success [72].

1.2. Self-Regulated Learning Models in E-Learning

E-learning means a special educational environment. The lack of presence of teachers and peers reduces the impact of social interaction. The existing social influence is carried out through communication mediated by technical means. At the same time, the student is in a familiar home environment, and immersion in an electronic educational environment requires the student’s own efforts. Shea and Bidjerano call this state “learning presence” [79]. So, the value of self-regulation is increasing. Therefore, there is a need to reconsider the existing models of self-regulation and apply them to e-learning. The new learning format requires not only taking into account changing conditions but including factors that were not of great importance for self-regulation in the traditional learning format. Although similar trends are observed at all levels of education, the most extensive and studied experience is in higher education.

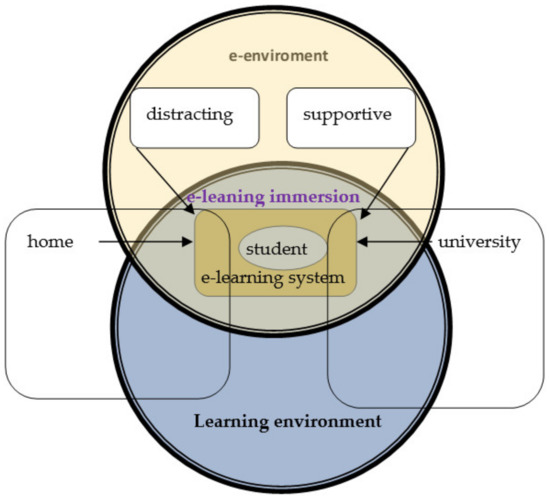

There is a lot of empirical research about the importance of self-regulation and self-efficacy in online courses [80,81,82,83]. In 2009, Barnard et al. offered the model of online self-regulation that included environment structuring, goal setting, time management, help seeking, task strategies, and self-evaluation [84]. A systematic review identifies the factors that were researched in the context of self-regulated learning in the online environment. They are metacognition, time management, effort regulation, peer learning, elaboration, rehearsal, organization, critical thinking, help seeking [85]. At the same time, the division of the environment into an online environment (extending far beyond learning) and a traditional learning environment (that can contain both online and offline elements) becomes reasonable. In many studies, such a division occurs for self-efficacy. For example, Tladi offers to distinguish distance learning self-efficacy and computer and online technologies self-efficacy [44]. However, the influence and capabilities of the electronic environment are underestimated. Internet is the usual living environment for young people. On the one hand, it means that this environment can serve as an additional powerful educational resource. On the other hand, it is distracting and time-consuming. Electronic and learning environments intersect and create a common e-learning space that is characterized by e-learning immersion (see Figure 2). The degree of e-learning immersion depends on both factors: the learning and the Internet environment, as well as the physical environment. Working in the e-learning system provided by the university requires that the student has certain conditions and technologies at home. Not only computer equipment, Internet connection, and other necessary devices, but even ergonomic factors such as furniture, lighting, noise, temperature, and chromatography can cause difficulties in e-learning [86]. The electronic environment not only limits the possibilities of the teacher’s direct influence on immersion but also can offer new ways of engagement (interactive elements [87], augmented [88] and virtual reality [89], mobile technology [90], etc.).

Figure 2.

E-learning as a fusion of electronic and learning environment.

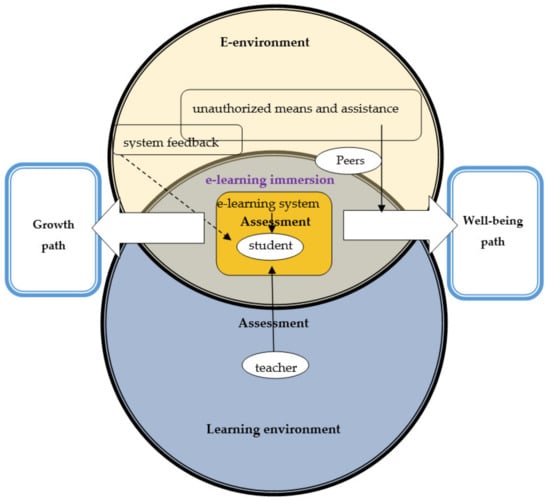

Boekaerts’s model (Figure 3) demonstrates how feedback can influence the choice of a student’s strategy. Boekaerts emphasizes the emotional part of self-regulation in learning [78]. Assessment and appraisal determine whether the students seek to avoid negative consequences and choose a coping strategy instead of a growth strategy.

Figure 3.

The dual processing self-regulation e-learning model.

In an e-environment, there are many ways to improve the quality of tasks performed using unacceptable methods. Moreover, if the goal of students is to get good grades, then various compensatory mechanisms and ingenuity begin to act. Moreover, the information resources of the digital environment allow students not to remember, but to quickly search for the necessary information, which sometimes leads to a violation of academic integrity. This is the strategy of avoiding problems (“well-being path”), which is connected with feedback in the form of marks, which can either be part of the e-learning system or teacher’s assessment. Especially in the case of automatic assessment in an e-learning system (for example, MOOC) the student may feel that the purpose of his/her behavior is to pass the test, and not to gain knowledge. According to the logic of the electronic environment, the easiest way to pass the test is to use the Internet to search for information or find help from a peer. Conversely, students consider the need to memorize the information provided by the e-environment itself in order to pass the test as a waste of time and resources. Moreover, those who choose the “path of growth” sometimes find themselves at a disadvantage, receiving lower grades than those who have taken advantage of the Internet environment. In this case, the social environment encourages the choice of a “well-being path” that becomes a social norm. Researchers note that the development of youth’s cognitive activity forms is accompanied by the mobility and flexibility of their value [91], therefore, academic dishonesty in the electronic environment can become a social practice [92]. Performing tasks in an electronic environment turns into a struggle between teachers who are looking for ways to get rid of students’ cheating [93,94], and students who, in turn, are looking for new ways to do this [95].

According to Boekaerts’ idea [78] Figure 3 demonstrates the possibility of choosing one of two paths: growth or well-being. Also, different forms of feedback and assessment in the online environment affect this choice (own verification of answers using the search engines, automatic answer check in the LMS, teacher evaluation and system feedback). Perhaps the e-environment requires a different approach to feedback, and the role of formal assessment is overestimated [96]. The electronic environment is conducive to seeking feedback opportunities. All behavior in the Internet environment leaves a digital footprint [97]. Data mining technics can be used as system feedback for students. Data from an e-learning system can serve as a starting point for self-monitoring itself. Gamification of this process allows students to launch additional mechanisms of motivation.

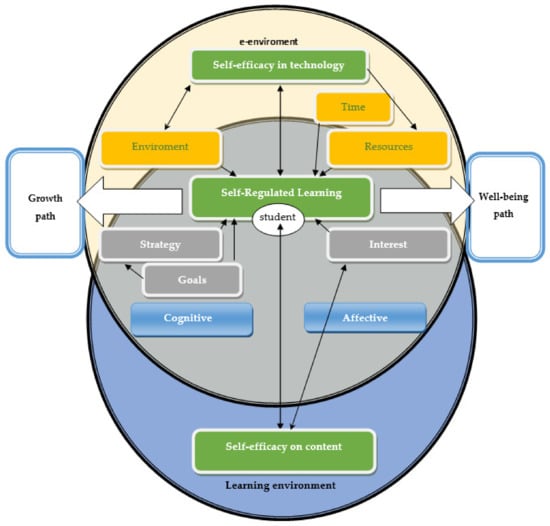

Self-regulated learning in the online environment has different dimensions. The self-regulated e-learning model presents two environments (Figure 4). Moreover, it includes dimensions such as goals, strategy, interests, environment, resources, and time, which were in the model of Zimmerman and Moylan [57]. Cognitive factors in the formation of self-regulation correspond to the cognitive activity of the subject in the assessment of events and imply the ability to navigate in the information field. Affective factors correspond to an emotional assessment of the situation, the specifics of which determine the individual reaction of the subject to the information impact [98]. As we can see in Figure 4, self-efficacy has two parts. One of them is traditionally connected with confidence in learning abilities. Another part is self-efficiency in human-system interaction. The experience of forced online learning during a pandemic shows that technological and human-machine interaction problems often came to the fore [4]. Factors such as self-regulation of the environment and self-regulation of resources go beyond the educational environment. When studying online, the student interacts with the Internet environment in a broader context, for example, using resources outside the given educational system. Self-regulation of time is a factor of particular importance in an online environment that tempts with a variety of activities (communication on social media, watching video content, playing video games, etc.). Working in the Internet environment, it is difficult not to be distracted by its various appeals. Competent distribution of time between learning, communication, entertainment requires self-regulation skills. Efficient time management in online learning environment is associated with high academic performance [65,99]. The study of self-regulation strategies revealed the dependence of academic performance on the feedback provided by the teacher. At the same time, the electronic environment allows students to use the advantages of learning analytics for self-control.

Figure 4.

The self-regulated e-learning model.

2. Materials and Methods

Higher educational institutions of St. Petersburg in March–April 2020 were among the first in the Russian Federation to switch to distance learning due to the threat of the spread of coronavirus infection. In this study, we interviewed students of various levels of education at St. Petersburg University, Peter the Great St. Petersburg Polytechnic University, The Herzen State Pedagogical University of Russia, as well as students of lyceums that are divisions of the universities represented. These universities are the largest in the humanities, technical and pedagogical fields not only in St. Petersburg but also in Russia. Before the total transition to distance learning, most students had some experience of electronic form of education in the blended learning format.

Initially, we conducted a qualitative study in each of the represented universities (St. Petersburg University, Peter the Great St. Petersburg Polytechnic University, The Herzen State Pedagogical University of Russia) in the format of focus groups. In total, 108 students took part in it, which were divided into nine groups. We have formed three groups in each of the universities. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the participants. Each group included 12 people to clarify the judgments presented in the quantitative assessment of the level of self-regulation in the electronic environment based on a questionnaire. The recordings of group discussions were processed using content analysis. We have included frequently occurring words and phrases in the list of possible answers for the main blocks of the questionnaire.

Table 1.

Demographic profiles.

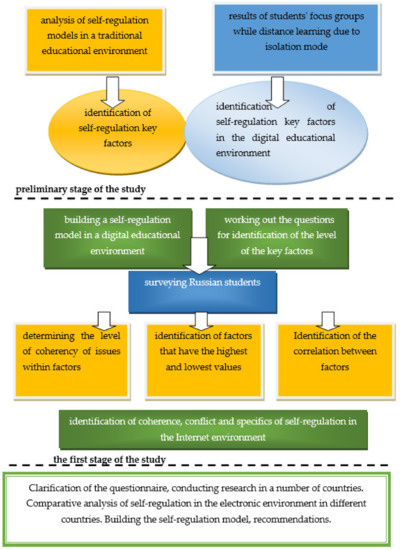

The sample is representative and consisted of 767 respondents, of which 351 respondents are men, 416 are women. Total of 51 respondents study at university schools, 681—undergraduate students, 29—graduate students, 6—postgraduate students (Table 2). More than 315 thousand people study at St. Petersburg universities according to higher education programs in the 2019/2020 academic year. Thus, observing a confidence level of 99 and a confidence interval of 5%, we obtain the minimum required sample size of 664 respondents (767 in the study). But we also would like to note that this study is only a part and the first stage in the project (Figure 5), which provides comparative (within the framework of partnerships with universities National Taiwan Normal University, University of Geneva, Sultan Qaboos University) and longitudinal methods.

Table 2.

Demographic profiles.

Figure 5.

Stages of the study.

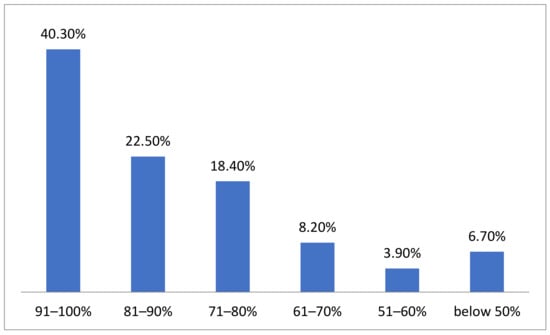

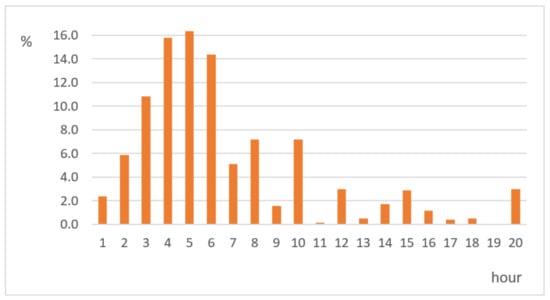

Moreover, to have an idea about the respondents, you should specify information about the percentage of courses that they took online and about the time spent on them (Figure 6 and Figure 7). Most of the respondents almost completely switched to the online format, which is 40.3%, and 22.5% of students indicated that the percentage of online courses was 81–90%. As for the time spent, it nearly coincides with the usual full-time training, although 102 respondents indicated 11–20 h a day.

Figure 6.

The percentage of online courses.

Figure 7.

The average number of hours per day for online.

In this paper, we used an interdisciplinary approach that allowed us to consider self-regulation in the learning process from the perspective of communication theories, pedagogy, and sociology of education. In addition, we used such research methods as the construction of logical circuits, graphical interpretation of theoretical information, and empirical data. As one of the effective research methods, we used a sociological survey of students, which was conducted on an Internet page specially created for this research. The use of the latter helped to collect the main part of the information on the research topic. In addition, statistical and mathematical methods were also used in the processing of questionnaires and responses of respondents.

A survey with a 5-point Likert-type response format, the values of which range from “completely agree” (5) to “strongly disagree” (1), was conducted in April 2020, which allowed the majority of respondents to get a clear idea of this learning format. The questionnaire consisted of 9 blocks (each of which contains from 4 to 9 statements), dedicated to such problems as Self-directed Learning Strategy, Self-directed Learning Interest, Self-regulated Learning, Self-efficacy of Online Learning on human-system interaction, Self-efficacy of Online Learning on content. The respondents took part in the study voluntarily and were invited to it through a mass e-newsletter.

In this study, with the help of Alf Cronbach, we checked the questionnaire. The total value for all 9 blocks of questions exceeds 0.67, which indicates a high internal coherence which is presented in Tables 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18 and 20. The collected data were analyzed using output statistics (Pearson correlation coefficient for calculating the correlation value between two variables) using the statistical analysis program SPSS 20. The results of the study are anonymized in terms of the students names and any other links that may identify the individual. Ethical approval was received from the Ethics Commission founded in the Institute of Humanities, Peter the Great St. Petersburg Polytechnic University, which is ruled by the code of ethics of the Russian Society of Sociologists.

3. Results

We presented statistical analysis and data from questionnaires with applications for nine researched blocks in the tables. Moreover, we indicated the results obtained from the respondents as a percentage. Table 3 shows the block of answers “Self-regulated training (General)”. The least support was given to the judgment about the purpose of learning, timing, and deadlines (“I always set a goal and make a schedule”—2.8), although this aspect is extremely important for self-organization. The value 2.9 corresponds to the decision to adjust the usual individual exam preparation plan. Respondents most often chose to study the so-called “weak” topics that cause them difficulties (I would spend more time reviewing weak topics—3, 4). A similar judgment about the study of “weak” topics has a rating of 3.2. The problems of adjustment and setting goals do not cause a strong response from respondents, but show values above average values («When setting a goal, I take into account the possible deadlines for achieving short-and long-term goals—3.1», «I would adjust my routine exam preparation program to pass it successfully»—3.2). The field of goals is disclosed in the next block and correlates with the above estimates of judgments. Table 4 shows summary of self-regulated learning (general) block statistics.

Table 3.

Self-regulated learning (general).

Table 4.

Summary of self-regulated learning (general) block statistics.

Table 5 shows the block of answers “self-regulated learning (goals related)”. It contains the lowest indicators of all the blocks presented above. The lower indicator of the statement “before learning online, I would test out the learning system” (the average value of 2.5) shows more confidence in the respondents’ abilities. The answer with the highest score is “after learning online, I would adjust learning methods based on learning outcomes. For example, taking notes during class” (average value 3.0). Perhaps this is due to the experience of passing online courses and having a clear idea of certain easily eliminated shortcomings. Students also note the peculiarities of their perception and physical or emotional state, while correcting their own goals due to a possible loss of concentration. The judgment on the recording of lectures received a rating of 2.9, not much behind the first place in this block. The general state of health, or for example a feeling of fatigue, was estimated on average to be lower and amounted to 2.7. Table 6 shows summary of statistics of the self-regulated learning (goals) block.

Table 5.

Self-regulated learning (goals).

Table 6.

Summary of statistics of the self-regulated learning (goals) block.

The “self-regulated learning (Environment related)” block, presented in Table 7, as well as the “self-efficiency of online learning on human-system interaction”, has the highest average value of 3.25. At the same time, the respondents supported such judgments as «before the start of online classes, I mark the time of classes in advance and come in time», «during online classes, I notice and try to correct any interference in the system that prevents us from perceiving the speech of others. For example, the echo of the speaker into the microphone» (average value 3.4). The lowest value is 3.0 for the statement “before online classes, I would check how suitable the place is for studying”, which indirectly indicates that online learning is not associated with the physical learning space, but rather focuses on the difficulties that may arise in the “virtual space”. Another similar judgment has almost the same average value «before starting online classes, I would adapt the space for studying so as not to be distracted by unimportant questions»—3.2. Table 8 shows summary of self-regulated learning (environment-related) block statistics.

Table 7.

Self-regulated learning (environment-related).

Table 8.

Summary of self-regulated learning (environment-related) block statistics.

Table 9 shows the results of the “self-regulated learning (Time related)” block. The highest average indicator of 2.9 falls on arguments such as “after an online lesson, I would start improving my action plan”, “before starting an online lesson, I would prefer to prepare well for it. For example, I try to finish my other things before classes start”. The lowest average indicator of 2.6 is for the phrase “to study online, I would put virtual classes in the schedule every day”. The average value of the judgment on the inclusion of such an activity as the revision of lecture material in the schedule was slightly higher—2.7. Thus, from the respondents’ answers, we see that daily classes are inferior to clear planning and preparation for such a type of study as online. Table 10 shows summary of statistics of self-regulated learning blocks (time-related).

Table 9.

Self-regulated learning (time related).

Table 10.

Summary of statistics of self-regulated learning blocks (time-related).

Table 11 is devoted to the block “self-regulated learning (resource-seeking related)”. From the point of view of resources, the least excitement among students is caused by difficulties with the Internet: “before online classes, I would ask to help solve any problems with the Internet”, which is an average of 2.5. Statements such as “after an online lesson, I would ask my fellow students about the content of material that I do not understand”, “after an online lesson, I would use available resources (for example, online learning sites) to improve learning efficiency” (the average value is 3.1 and 3.0, respectively), indicate a search for any available resources, including the environment of fellow students. But the tips and ideas of fellow students regarding improving the effectiveness of online learning, on the contrary, were rated low by respondents (2.6). Table 12 shows summary of statistics of self-regulated learning block (resource-seeking related).

Table 11.

Self-regulated learning (resource-seeking related).

Table 12.

Summary of statistics of self-regulated learning block (resource-seeking related).

Table 13 shows the data of the “self-efficiency of online learning on human-system interaction” block. In four out of six statements, the average indicator is 3.3: «As long as I try hard enough, I can solve all human–system interaction problems I have during learning online», «whenever new human–system interaction problems arise, I can solve them on my own», «in my opinion, all that is required is to make more effort to solve human–system interaction problems», «when I encounter human–system interaction problems, I can find ways to solve them». These answers of the respondents indicate to us a high level of confidence in solving problems that arise in the human-system field. The lowest value is associated with the occurrence of unexpected problems such as “I am confident that I cope with unexpected problems of human-system interaction”, which is 3.1 on average. Moreover, from the point of view of the coverage of the problem field, the answer “In a word, I can safely cope with problems while studying online” is gaining an average value of 3.2. Which generally demonstrates a small gap in estimates, but still focuses our attention on greater confidence in judgments concerning the human-system interaction. Table 14 shows summary of statistics of self-efficacy block of online learning on human-system interaction.

Table 13.

Self-efficacy of online learning on human-system interaction.

Table 14.

Summary of statistics of self-efficacy block of online learning on human-system interaction.

Table 15 shows the data for the “self-efficacy of online learning on content” block. The average values for the presented statements fluctuate on average about a value equal to 3. The largest deviation is 3.2 for such statements as “Facing a homework assignment that is difficult to complete, I can find a solution”, “While online study I am sure that I can find solutions for completing my homework”. Both of them are related to homework and indicate the respondents’ confidence in their abilities in this type of learning activity. Moreover, three judgments are marked with the same average value of 3.1, which emphasize the importance of overcoming difficulties and diligence: «As long as I try hard enough, I can understand the concept of online education», «I would overcome any difficulties I might encounter, for example, problems with understanding the content», «In short, I can confidently overcome the difficulties of online learning». The opinion “studying online, I can independently understand any new concept of the course” received the least support (the average value is 2.9). Table 16 shows summary of statistics of self-efficacy block of online learning on content.

Table 15.

Self-efficacy of online learning on content.

Table 16.

Summary of statistics of self-efficacy block of online learning on content.

We propose to consider the “self-directed learning strategy” block, presented in Table 17. The opinions supported by the majority of students are of interest. Thus, the main strategy is related to the search for information on the Internet (average value 3.5), but a little fewer respondents supported the judgment “I would look for solutions on my own when I am having trouble using the learning system” (average value 3.4), and the least popular answer (average value 2.5) is “frequent access to course materials”. Regular information search (3.0) and the effectiveness of curriculum development (2.5) in this block of judgments have average values. This block shows us a fairly significant difference between the lowest and the most highly valued judgment per unit. Table 18 shows summary of statistics of self-directed learning strategy block.

Table 17.

Self-directed learning strategy.

Table 18.

Summary of statistics of self-directed learning strategy block.

Table 19 shows the self-directed learning interest block. The answers related to self-study and independent research received the least support (for example, I like to explore everything on my own, when new concepts and new things appear. I like to study on my own—2.9). At the same time, respondents point out that they want to complete the task to the end, no matter how difficult it may be. Furthermore, in such a way that they can complete it among the first students who have done it (the average value for these two statements is 3.3). The judgment about the individual search for answers in case of misunderstanding of complex concepts received an average rating (3.0). Table 20. Shows summary of statistics of self-directed learning interest block

Table 19.

Self-directed learning interest.

Table 20.

Summary of statistics of self-directed learning interest block.

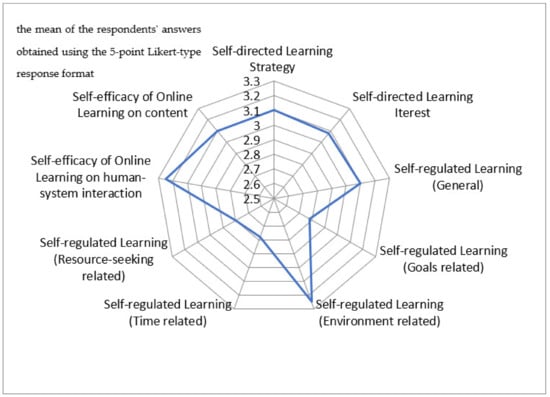

Figure 8 shows a diagram that displays the average values for each of the topic blocks. The highest indicators are associated with self-regulation in the field of environment, and self-efficiency on human-system interaction, which demonstrates the dominance of e-environment.

Figure 8.

Characteristics of self-regulated e-learning.

Table 21 shows the correlation coefficients between the main blocks to refine the research model. We found high correlations on the Chaddock scale (0.7 < r < 0.9) between the blocks self-regulated learning (goals) and self-regulated learning (resource-seeking related), self-efficacy of online learning on human-system interaction, and self-directed learning interest. It is also worth highlighting self-regulated learning block (environment-related), which has high and ultra-high connections with almost all blocks, excluded self-directed learning strategy. The authors indicate the presence of correlation coefficients of more than 0.9 between several blocks. This is the basis for completing the model at the next stage of the study.

Table 21.

Correlation coefficients among variables of the study.

4. Discussion

Reducing the influence of the characteristics inherent in the traditional learning environment, and at the same time increasing the impact of the electronic environment, both factors place high demands on students’ self-regulation. Self-regulation in e-learning can be considered as a number of mutually influencing factors. Some of them are traditional for any educational format, others change in accordance with the online environment, and others are unique for it. Education affects the cognitive and affective spheres. Self-regulation correlates with goals, strategies, and interests in learning. Interaction with the environment, resources, and even time management take specific forms in the electronic environment. In addition, self-efficiency plays a special role in human–machine interaction. This study confirms the relationship between the listed indicators of self-regulation in the electronic environment. In addition, we can conclude that a high degree of self-regulation in the electronic environment turns out to be quite difficult to achieve for students. Students are least capable of pre-setting goals and planning time, which requires special immersion in learning environment.

In the model presented in the article, we focused on the conflict between traditional education and practice in the online environment. The survey results show that the students are most successful to overcome the difficulties of e-learning related to self-regulation, at environment part and human-machine self-efficiency. So, the electronic environment can sometimes dominate the learning one (which is confirmed by the higher rates connected with the electronic environment). The retention of traditional forms of assessment and evaluation is in contradiction with the usual features of existence in the electronic environment. The contradiction between the “growth” and “well-being” paths (described at the model of Boekaerts [78]) even more provokes the choice of a simpler solution at the electronic environment. At the moment, teachers and IT specialists are formally struggling with the problem of students searching for answers on the Internet and unauthorized cooperation with peers. But it is more important that the student has self-learning goals and self-learning strategies, and uses the great opportunities of the electronic environment for development, and not for cheating. “Learning to learn” is one of the key competencies in future work [100,101,102].

The e-learning environment is strikingly different from the traditional learning environment. One of the features of the online environment is the ability to record the student’s activities. Self-learning data can serve as a way of self-control. Many parameters can be explored to evaluate the characteristics of educational strategy, which can allow students to analyze learning in an online environment. For example, Tracker prototype widget designed to compare behaviors of learners [103], ProSOLO software provides tracking of students’ learning processes and course competencies [104], NoteMyProgress presents the number of entries, number of interactions with the different visualizations and functionalities, frequency of entries [105]). Visual learning analytics could show the students time dynamics of their e-learning [106,107]. Moreover, learning analytics system could generate recommendations [108]. However, e-learning environment potential has largely not been employed widely [109,110]. Technological solutions can be proposed to optimize the search for appropriate educational resources [111].

This study is the first stage of scientific work devoted to self-regulation in the electronic environment. In the study, authors evaluated key factors, identified correlations that serve as a basis for the development of the issues and improvement of the presented model. Further research will allow us to compare the strongest and weakest factors of self-regulation in a dynamic perspective and in different countries. The relative technical ease of switching to online education during the lockdown is sometimes misleading. The idea that the electronic environment does not affect the essence of the educational process seems to us wrong. In fact, further in-depth research is needed to clarify how e-environment changes traditional learning models.

At the same time, the results of empirical research have shown that the model used for evaluating e-learning needs further clarification and development. In the electronic environment, it is necessary to separate the processes that help and hinder educational self-regulation in order to see the real picture of the educational process. The components of self-regulated learning (most notably General, Goals and Environment) need to refine the assertions used to survey to avoid similarities. In further studies, it is necessary also to clarify the direction of the influence of self-regulation factors on each other.

5. Research Limitations

Our research has some limitations. We conducted studies in one major Russian city. It is necessary to expand the sample for further analysis of self-regulation in the electronic environment. In addition, we did it in the situation of transition to fully e-learning during the pandemic. Adaptation to new conditions and the psychological state of students could affect the results. Moreover, we depended on the students’ assessments and opinions, which may be slightly biased in some perspectives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.B. and J.-C.H.; methodology, D.B. and J.-C.H.; validation, D.B. and V.L.; formal analysis, D.B. and V.L.; investigation, D.B., V.L. and T.N.; data curation, V.L.; writing—original draft preparation, D.B. and V.L.; writing—review and editing, T.N.; visualization, D.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research is partially funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation under the strategic academic leadership program ‘Priority 2030’ (Agreement 075-15-2021-1333 dated 30 September 2021).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was received from the Ethics Commission founded in the Institute of Humanities, Peter the Great St. Petersburg Polytechnic University (24.03.20 No. 11), which is ruled by the code of ethics of the Russian Society of Sociologists.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions of privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, C. Suspending classes without stopping learning: China’s education emergency management policy in the COVID-19 outbreak. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubtsova, A.; Odinokaya, M.; Krylova, E.; Smolskaia, N. Problems of Mastering and Using Digital Learning Technology in the Context of a Pandemic. In Knowledge in the Information Society; PCSF 2020, CSIS 2020; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 184, pp. 324–337. [Google Scholar]

- Alsoud, A.R.; Harasis, A.A. The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Student’s E-Learning Experience in Jordan. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almazova, N.; Krylova, E.; Rubtsova, A.; Odinokaya, M. Challenges and Opportunities for Russian Higher Education amid COVID-19: Teachers’ Perspective. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valieva, F.; Fomina, S.; Nilova, I. Distance Learning during the Corona-Lockdown: Some Psychological and Pedagogical Aspects. In Knowledge in the Information Society; PCSF 2020, CSIS 2020; Bylieva, D., Nordmann, A., Shipunova, O., Volkova, V., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 184, pp. 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Pokrovskaia, N.N.; Tyulin, A.T. Psychological Features of the Regulative Mechanisms Emerging in the Digital Space. Technol. Lang. 2021, 2, 106–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samorodova, E.A.; Belyaeva, I.G.; Bakaeva, S.A. Analysis of communicative methods effectiveness in teaching foreign languages during the coronavirus epidemic: Distance format. XLinguae 2021, 14, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarneh, B.M.; Alshurideh, M.T.; Al Kurdi, B.H.; Obeidat, Z. The Impact of COVID-19 on E-learning: Advantages and Challenges. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Vision (AICV2021); Hassanien, A.E., Haqiq, A., Tonellato, P.J., Bellatreche, L., Goundar, S., Azar, A.T., Sabir, E., Bouzidi, D., Eds.; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 1377, pp. 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Meder, C. Counselor Education Delivery Modalities: Do They Affect Student Learning Outcomes? Ph.D. Thesis, Regent University, Virginia Beach, VA, USA, May 2013. Database 2013 UMI Number: 357359. [Google Scholar]

- Lyke, J.; Frank, M. Comparison of student learning outcomes in online and traditional classroom environments in a psychology course. J. Instr. Psychol. 2012, 39, 245–250. [Google Scholar]

- Waschull, S.B. The Online Delivery of Psychology Courses: Attrition, Performance, and Evaluation. Teach. Psychol. 2001, 28, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, P.E.; Clariana, R.B. Achievement predictors for a computer-applications module delivered online. J. Inf. Syst. Educ. 2020, 11, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Upton, D.; Cooper, C.D. Online Health Psychology: Do Students Need It, Use It, Like It and Want It? Psychol. Learn. Teach. 2004, 3, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Jaggars, S.S. The effectiveness of distance education across Virginia’s community colleges: Evidence from introductory college-level math and English courses. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 2011, 33, 360–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.C.; Fetzner, M.J. The road to retention: A closer look at institutions that achieve high course completion rate. J. Asynchronous Learn. Netw. 2009, 13, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njenga, J.K.; Fourie, L.C.H. The myths about e-learning in higher education. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2010, 41, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, B.; McFadden, C. Attrition in Online and Campus Degree Programs. Online J. Distance Learn. Adm. 2009, 12. Available online: https://www.westga.edu/~distance/ojdla/summer122/patterson112.html (accessed on 16 October 2021).

- Holder, B. An investigation of hope, academics, environment, and motivation as predictors of persistence in higher education online programs. Internet High. Educ. 2007, 10, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, V.P. Relationships between Student Characteristics and Student Persistence in Online Classes at a Community College (Order No. 3485377). Ph.D. Thesis, University of California, Long Beach, CA, USA, May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, S. Understanding the context of distance students: Differences in on- and off- campus engagement with an online learning environment. J. Open Flex. Distance Learn. 2012, 16, 70–82. [Google Scholar]

- Van Doorn, J.R.; Van Doorn, J.D. The quest for knowledge transfer efficacy: Blended teaching, online and in-class, with consideration of learning typologies for non-traditional and traditional students. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neff, K.S.; Donaldson, S.I. Teaching Psychology Online: Tips and Strategies for Success; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, J.; Kumar, P. Students’ Perceptions of Teaching and Social Presence. Int. J. Web-Based Learn. Teach. Technol. 2015, 10, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appana, S. A review of benefits and limitations of line learning in the context of the student, the instructor, and the tenured faculty. Int. J. E-Learn. 2008, 7, 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Song, H.; Kim, J.; Park, N. I Know My Professor: Teacher Self-Disclosure in Online Education and a Mediating Role of Social Presence. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2019, 35, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaytan, J. Factors Affecting Student Retention in Online Courses: Overcoming this Critical Problem. Career Tech. Educ. Res. 2013, 38, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuensch, K.L.; Aziz, S.; Ozan, E.; Kinshore, M.; Tabrizi, M.H.N. Pedagogical characteristics of online and face-to-face classes. Int. J. E-Learn. 2008, 7, 523–532. [Google Scholar]

- Bylieva, D.; Moccozet, L. Technology-Mediated Communication for Educational Purposes (in Russia and Switzerland). Technol. Lang. 2021, 2, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewan, M.A.A.; Murshed, M.; Lin, F. Engagement detection in online learning: A review. Smart Learn. Environ. 2019, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Cheng, M. Exploring factors impacting student engagement in open access courses. Open Learn. J. Open Distance E-Learn. 2019, 34, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christenson, S.; Reschly, A.; Wylie, C. Handbook of Research on Student Engagement; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Floratos, N.; Guasch, T.; Espasa, A. Recommendations on Formative Assessment and Feedback Practices for stronger engagement in MOOCs. Open Prax. 2015, 7, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Al-Hendawi, M. Academic engagement of students with emotional and behavioral disorders: Existing research, issues, and future directions. Emot. Behav. Difficulties 2012, 17, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Jang, S. Motivation in online learning: Testing a model of self-determination theory. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, M. Student perceptions of support services and the influence of targeted interventions on retention in distance education. Distance Educ. 2010, 31, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, D. Leadership behavior and its impact on student success and retention in online graduate education. Acad. Educ. Leadersh. J. 2013, 17, 13–37. [Google Scholar]

- Artino, A.R. Promoting academic motivation and self-regulation: Practical guidelines for online instruction. TechTrends 2008, 52, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wladis, C.; Hachey, A.C.; Conway, K. An investigation of course-level factors as predictors of online STEM course outcomes. Comput. Educ. 2014, 77, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lung-Guang, N. Decision-making determinants of students participating in MOOCs: Merging the theory of planned behavior and self-regulated learning model. Comput. Educ. 2019, 134, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizilcec, R.F.; Pérez-Sanagustín, M.; Maldonado, J.J. Self-regulated learning strategies predict learner behavior and goal attainment in Massive Open Online Courses. Comput. Educ. 2017, 104, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leasure, A.; Davis, L.; Thievon, S. Comparison of student outcomes and preferences in a traditional vs. World Wide Web-based baccalaureate nursing research course. J. Nurs. Educ. 2000, 39, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaytan, J. Comparing Faculty and Student Perceptions Regarding Factors That Affect Student Retention in Online Education. Am. J. Distance Educ. 2015, 29, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormrod, J.E. Social cognitive views of learning. In Educational Psychology: Developing Learners; Smith, P.A., Ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2011; pp. 352–354. [Google Scholar]

- Tladi, L.S. Perceived ability and success: Which self-efficacy measures matter? A distance learning perspective. Open Learn. J. Open Distance E-Learn. 2017, 32, 243–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, S. Investigating students’ perceived satisfaction, behavioral intention, and effectiveness of e-learning: A case study of the Blackboard system. Comput. Educ. 2008, 51, 864–873. [Google Scholar]

- Gore, P.A., Jr. Academic self-efficacy as a predictor of college outcomes: Two incremental validity studies. J. Career Assess. 2006, 14, 92–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenson, R.; Boyles, G.; Weaver, A. Emotional Intelligence as a Predictor of Success in Online Learning. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2008, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, S. Distance Learning at the Tipping Point: Critical Success Factors to Growing Fully Online Distance Learning Programs; Eduventures, Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Safford, K.; Stinton, J. Barriers to blended digital distance vocational learning for non-traditional students. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2016, 47, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, M.; Burrus, S.; Ferguson, K. Factors that influence student attrition in online courses. Online J. Distance Learn. Adm. 2016, 19, 211–231. [Google Scholar]

- Ware, J. Earning an MBA online: Internet-based programs offer flexibility. Fla. Trend 2014, 56, 84. [Google Scholar]

- Leeds, E.; Campbell, S.; Baker, H.; Ali, R.; Brawley, D.; Crisp, J. The impact of student retention strategies: An empirical study. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2013, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochester, C.D.; Pradel, F. Students’ Perceptions and Satisfaction with a Web-Based Human Nutrition Course. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2008, 72, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Inzlicht, M.; Werner, K.M.; Briskin, J.L.; Roberts, B.W. Integrating Models of Self-Regulation. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2021, 72, 319–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boekaerts, M.; Corno, L. Self-Regulation in the Classroom: A Perspective on Assessment and Intervention. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 54, 199–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asarnow, J.R.; Meichenbaum, D. Verbal Rehearsal and Serial Recall: The Mediational Training of Kindergarten Children. Child Dev. 1979, 50, 1173–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, M.J.; Thoresen, C.E. Behavioral Self-Control: Power to the Person. Educ. Res. 1972, 1, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, B.J.; Schunk, D.H. Self-Regulated Learning and Performance. In Handbook of Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance; Zimmerman, B.J., Schunk, D.H., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Akamatsu, D.; Nakaya, M.; Koizumi, R. Effects of Metacognitive Strategies on the Self-Regulated Learning Process: The Mediating Effects of Self-Efficacy. Behav. Sci. 2019, 9, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boekaerts, M.; Pintrich, P.R.; Zeidner, M. Self-Regulation: An Introductory Overview. In Handbook of Self-Regulation; Boekaerts, M., Zeidner, M., Pintrich, P.R., Eds.; Elsevier: San Diego, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, B.J. A social cognitive view of self-regulated academic learning. J. Educ. Psychol. 1989, 81, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. From Cognitive Modeling to Self-Regulation: A Social Cognitive Career Path. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 48, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odinokaya, M.; Krepkaia, T.; Karpovich, I.; Ivanova, T. Self-Regulation as a Basic Element of the Professional Culture of Engineers. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzziferro, M. Online Technologies Self-Efficacy and Self-Regulated Learning as Predictors of Final Grade and Satisfaction in College-Level Online Courses. Am. J. Distance Educ. 2008, 22, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, S.G.; Paris, A.H. Classroom Applications of Research on Self-Regulated Learning. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 36, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P.R. The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning. In Handbook of Self-Regulation; Boekaerts, M., Pintrich, P.R., Zeidner, M., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 452–502. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.; Cervone, D. Differential engagement of self-reactive influences in cognitive motivation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1986, 38, 92–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panadero, E. A Review of Self-regulated Learning: Six Models and Four Directions for Research. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J.; Schunk, H.D. Self-Regulated Learning and Academic Achievement: Theoretical Perspectives, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2008; ISBN 0-0858-3560-1. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, B.J.; Moylan, A.R. Self-regulation: Where metacognition and motivation intersect. In Handbook of Metacognition in Education; Hacker, D.J., Dunlosky, J., Graesser, A.C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 299–315. [Google Scholar]

- Sadi, Ö.; Uyar, M. The relationship between self-efficacy, self-regulated learning strategies and achievement: A path model. J. Balt. Sci. Educ. 2013, 12, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Roick, J.; Ringeisen, T. Students’ math performance in higher education: Examining the role of self-regulated learning and self-efficacy. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2018, 65, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, A.; Karpinski, A.C.; Lepp, A.; Barkley, J. Online and face-to-face classroom multitasking and academic performance: Moderated mediation with self-efficacy for self-regulated learning and gender. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 102, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadari-Koosha, M.; Moghadasi-Amiri, M.; Cheraghi, F.; Mozafari, H.; Imani, B.; Zandieh, M. Self-Efficacy, Self-Regulated Learning, and Motivation as Factors Influencing Academic Achievement Among Paramedical Students: A Correlation Study. J. Allied Health 2020, 49, 145E–152E. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, J.A.; Plumley, R.D.; Urban, C.J.; Bernacki, M.L.; Gates, K.M.; Hogan, K.A.; Demetriou, C.; Panter, A.T. Modeling temporal self-regulatory processing in a higher education biology course. Learn. Instr. 2019, 72, 101201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boekaerts, M.; Rozendaal, J.S. Self-regulation in Dutch secondary vocational education: Need for a more systematic approach to the assessment of self-regulation. In Zeitschrift für Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik; Euler, D., Lang, M., Pätzold, G., Eds.; Franz Steiner: Stuttgart, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Boekaerts, M. Emotions, emotion regulation, and self-regulation of learning. In Handbook of Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance; Zimmerman, B.J., Schunk, D.H., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 408–425. [Google Scholar]

- Shea, P.; Bidjerano, T. Learning presence: Towards a theory of self-efficacy, self-regulation, and the development of a communities of inquiry in online and blended learning environments. Comput. Educ. 2010, 55, 1721–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.-H.; Shen, D. Self-regulation in online learning. Distance Educ. 2013, 34, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Watson, S.L.; Watson, W.R. Systematic literature review on self-regulated learning in massive open online courses. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2019, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artino, A.R.; Jones, K.D. Exploring the complex relations between achievement emotions and self-regulated learning behaviors in online learning. Internet High. Educ. 2012, 15, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruso, J.L.; Stefaniak, J.E. The Use of Self-Regulated Learning Measure Questionnaires as a Predictor of Academic Success. TechTrends 2016, 60, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, L.; Lan, W.Y.; To, Y.M.; Paton, V.O.; Lai, S.-L. Measuring self-regulation in online and blended learning environments. Internet High. Educ. 2009, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, J.; Poon, W.L. Self-regulated learning strategies & academic achievement in online higher education learning environments: A systematic review. Internet High. Educ. 2015, 27, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez Monzón, N.; Jadán-Guerrero, J.; Almeida, R.R.; Valdivieso, K.E.D. E-learning Ergonomic Challenges during the Covid-19 Pandemic. In Advances in Human Factors in Training, Education, and Learning Sciences; Springer: Cham, Swizerland, 2021; pp. 324–330. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, A.P.; Soares, F. Interactive Learning Materials Contribution for Students’ Engagement in E-Learning of Mathematics Contents: A Case Study during the Covid-19 Pandemic. In Proceedings of the 15th International Technology, Education and Development Conference (INTED 2021), Valencia, Spain, 8–9 March 2021; pp. 329–335. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem, M.; Kamarudin, S.; Shoaib, H.M.; Nasar, A. Influence of augmented reality app on intention towards e-learning amidst COVID-19 pandemic. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfarsi, G.; Yusof, A.B.M.; Tawafak, R.M.; Malik, S.I.; Mathew, R.; Ashfaque, M.W. Instructional Use of Virtual Reality in E-Learning Environments. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Advent Trends in Multidisciplinary Research and Innovation (ICATMRI), Buldhana, India, 30 December 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi, S.F.H.; Osmanaj, V.; Ali, O.; Zaidi, S.A.H. Adoption of mobile technology for mobile learning by university students during COVID-19. Int. J. Inf. Learn. Technol. 2021, 38, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipunova, O.; Pozdeeva, E.; Evseeva, L.; Mureyko, L.V. Young Students’ Attitude toward Expert Knowledge. In Knowledge in the Information Society; PCSF 2020, CSIS 2020; Bylieva, D., Nordmann, A., Shipunova, O., Volkova, V., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 184, pp. 391–400. [Google Scholar]

- Herdian, H.; Mildaeni, I.N.; Wahidah, F.R. “There are Always Ways to Cheat” Academic Dishonesty Strategies during Online Learning. J. Learn. Theory Methodol. 2021, 2, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, J.; Kohlbeck, M. Addressing cheating when using test bank questions in online Classes. J. Account. Educ. 2020, 52, 100671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bylieva, D.; Zamorev, A.; Lobatyuk, V.; Anosova, N. Ways of Enriching MOOCs for Higher Education: A Philosophy Course. In Knowledge in the Information Society; PCSF 2020, CSIS 2020; Bylieva, D., Nordmann, A., Shipunova, O., Volkova, V., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 184, pp. 338–351. [Google Scholar]

- Bylieva, D.; Lobatyuk, V.; Tolpygin, S.; Rubtsova, A. Academic dishonesty prevention in e-learning university system. In Trends and Innovations in Information Systems and Technologies, Proceedings of the 8th World Conference on Information Systems and Technologies, Budva, Montenegro, 7–10 April 2020; Rocha, A., Adeli, H., Reis, L.P., Costanzo, S., Orovic, I., Moreira, F., Eds.; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 1161, pp. 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Caingcoy, M.E.; Lepardo, R.J.L. School Performance, Leadership and Core Behavioral Competencies of School Heads: Does Higher Degree Matter? J. Adv. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2020, 6, 1190–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozdeeva, E.; Shipunova, O.; Popova, N.; Evseev, V.; Evseeva, L.; Romanenko, I.; Mureyko, L. Assessment of Online Environment and Digital Footprint Functions in Higher Education Analytics. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezovskaya, I.; Shipunova, O.; Kedich, S.; Popova, N. Affective and Cognitive Factors of Internet User Behaviour. In Knowledge in the Information Society; PCSF 2020, CSIS 2020; Bylieva, D., Nordmann, A., Shipunova, O., Volkova, V., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 184, pp. 38–49. [Google Scholar]

- ChanLin, L.-J. Learning strategies in web-supported collaborative project. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2012, 49, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leontyeva, V.L.; Pokrovskaia, N.N.; Ababkova, M.Y. Intellectual Networking in Digital Education–Improving Testing for Enhanced Transfer of Knowledge. In Intellectual Networking in Digital Education–Improving Testing for Enhanced Transfer of Knowledge; Bylieva, D., Nordmann, A., Shipunova, O., Volkova, V., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 171–191. [Google Scholar]

- Laakso-Manninen, R.; Tuomi, L. Professional Higher Education Management–Best Practices from Finland; Professional Publishing Finland Ltd.: Helsinki, Finland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Demidov, V.; Mokhorov, D.; Mokhorova, A.; Semenova, K. Professional public accreditation of educational programs in the education quality assessment system. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 244, 11042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.; Chen, G.; van der Zee, T.; Hauff, C.; Houben, G.-J. Retrieval Practice and Study Planning in MOOCs: Exploring Classroom-Based Self-regulated Learning Strategies at Scale. In Adaptive and Adaptable Learning; EC-TEL 2016; Verbert, K., Sharples, M., Klobučar, T., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 9891, pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, S.; Joksimović, S.; Kovanović, V.; Gašević, D.; Siemens, G. Recognising learner autonomy: Lessons and reflections from a joint x/c MOOC. In Research and Development in Higher Education: Learning for Life and Work in a Complex World; Thomas, T., Levin, E., Dawson, P., Fraser, K., Hadgraft, R., Eds.; Higher Education Research and Development: Milperra, Australia, 2015; Volume 38, pp. 117–129. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Álvarez, R.; Maldonado-Mahauad, J.; Pérez-Sanagustín, M. Design of a Tool to Support Self-Regulated Learning Strategies in MOOCs. J. Univers. Comput. Sci. 2018, 24, 1090–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noroozi, O.; Alikhani, I.; Järvelä, S.; Kirschner, P.A.; Juuso, I.; Seppänen, T. Multimodal data to design visual learning analytics for understanding regulation of learning. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 100, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasheng, Y.; Xu, W.; Yu, Y. Research on visualization methods of online education data based on IDL and hadoop. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Res. 2017, 7, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siadaty, M.; Gašević, D.; Hatala, M. Measuring the impact of technological scaffolding interventions on micro-level processes of self-regulated workplace learning. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 59, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viberg, O.; Khalil, M.; Baars, M. Self-regulated learning and learning analytics in online learning environments. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Learning Analytics & Knowledge, Frankfurt, Germany, 23–27 March 2020; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 524–533. [Google Scholar]

- Samorodova, E.A.; Belyaeva, I.G.; Birova, J.; Kobylarek, A. Technology-Based Methods for Creative Teaching and Learning of Foreign Languages. In Technology, Innovation and Creativity in Digital Society; PCSF 2021; Bylieva, D., Nordmann, A., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 345, pp. 797–810. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, B.; Zhang, W. Application of digital image processing technology in online education under COVID-19 epidemic. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2013, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).