Using Web Video Conferencing to Conduct a Program as a Proposed Model toward Teacher Leadership and Academic Vitality in the Philippines

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Professional Development Programs

1.2. Teacher Leadership

1.3. Action Research

1.4. Technology Integration

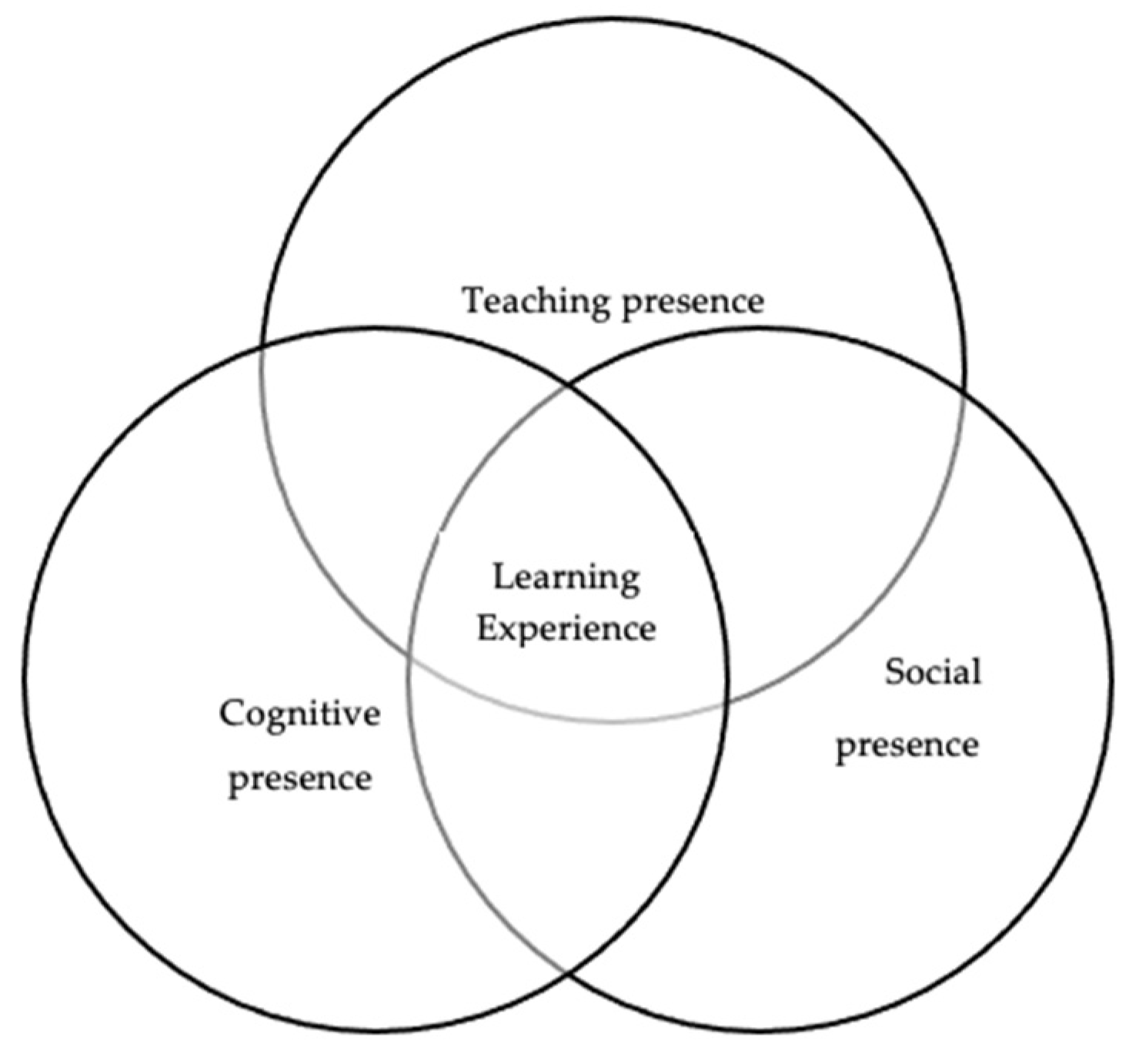

1.5. Community of Inquiry (CoI) Framework

1.6. Research Problems

- 1.

- How do the teachers perceive and understand action research in terms of:

- 1.1.

- the principles of AR;

- 1.2.

- attitudes toward the conduct of AR;

- 1.3.

- processes in performing the AR?

- 2.

- Is there a significant difference to the teachers’ perception and understanding of action research before and after the training?

- 3.

- How do the teachers perceive technology integration in terms of:

- 3.1.

- their proficiency on the use of hardware and software;

- 3.2.

- the factors that influence their adoption and integration of technology in teaching;

- 3.3.

- their concerns on technology integration in education?

- 4.

- How do the teachers sustain a desired level of research excellence?

- 5.

- What is the effect of the use of WVC on the conduct of STAR program as a model toward teacher leadership and academic vitality?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Research Participants

2.3. Research Instruments

2.4. Research Ethics

2.5. Research Procedure

2.6. Data Collection

2.6.1. Quantitative Phase

2.6.2. Qualitative Phase

2.7. Data Analysis

2.7.1. Quantitative Data

2.7.2. Qualitative Data

3. Results

3.1. Session 1

“Thank you for the beautiful and productive day. Happy to be part of the team.”

“Thank you for organizing this AR seminar. It is part of your dissertation, but you are able to help many.”

“Contrary to what our good professors mentioned, I didn’t come prepared. But the lecture this morning helped distill my thoughts and prompted me to focus on a possible topic which, for me, is a pressing need in school. The comments were helpful in putting more structure and direction to my proposed AR. Excited to work on this and looking forward to more productive Saturdays in the coming weeks!”

“It is indeed a informative session in which theory and practice are dynamically fused resulting in a paradigmatic understanding of everything discussed and shared in this academic session. My sincerest gratitude to all, our resource persons, organizers and fellow educators for an amazing sharing of knowledge.”

“Action research is #careergoals. It reflects one’s teaching practices. It is a self-evaluation of one’s role to spark good change. Simply, it is about me.”

“Thank you for this opportunity. The session was informative and helpful especially to teachers who are into research writing.”

“Our session today is not only helpful to me as a research enthusiast, but also as a research teacher myself. I find the introduction (characteristics, principles of AR, etc.) helpful to my own discussion of AR next term. Hopefully, I may be given permission to adapt the slides so I could share what I have acquired to my students in the NHS.”

“This first meeting provided informative guide in creating a research proposal. The 5-step guide really helped me in eliminating the distractions in planning a research proposal. This helped me come up with an action research that I am happy to share to the community once completed”

3.2. Session 2

3.3. Session 3

3.4. Session 4

“Participants of STAR 1 were volunteers. They enlisted on their own despite knowing the rudiments of the workshop. They know it will be held in nine (9) Saturdays with three (3) hours per session. They were fully aware that engagement in AR is an additional task. However, they were ready. They were excited with the tasks ahead of them. Perhaps, because they were intrinsically motivated, highly engaged to grow professionally, and most of all—research enthusiasts.”

3.5. Session 5

3.6. Session 6

3.7. Session 7

3.8. Session 8

3.9. Session 9

“To all the presenters, my sincerest CONGRATULATIONS! I feel so happy and inspired by the quality of action research work that you are all doing!”

“Kudos for her leadership in organizing the STAR … Animo!”

“Thank you, Sir! You have all inspired us to continue infecting others with the AR virus! Animo!”

“Thank you so much for the opportunity to be trained by research scholars. In our 9-week webinar, I became a fan! I cannot thank you enough for motivating us to be better educators. Thank you very much! I am working towards finishing my paper soon.”

“Thank you for sharing your insights with us. Teachers like you inspire students and your colleagues and more so to us AR facilitators. Let us continue to empower each other and ensure quality educationin our institution!”

“Thanks for the good realizations, and appreciations re the conduct of the AR webinar workshop … and the nice words uttered!”

“This is the virus we want to have. We’re grateful for your wisdom and expertise! Looking forward for more! God bless your heart always. Cheers and blessings!”

“Thank you so much for the gift of the support group that helps each other to shine and spark light to others as well. Thank you for being my constant star when I am lost in my journey towards the completion of my AR. Your constant guidance makes the journey meaningful and easy. It is a blessing to work with you and it’s a privilege to have been mentored by you. I am humbled and honored of how you dedicated your precious time with us despite your busy schedules. Know that this journey will not end with my presentation here. I want to pay it forward to affect the AR virus to all educators. To my fellow participants, congratulations.”

“Our sincerestthanksfor your passion, dedication, and boundless patience in leading us towards this program’s culmination. You are not done with is yet, that we can assure you as we intend to put up the Research Commons which we hope you will take on as advisers.”

3.10. Research Question 1

- 1.

- How do the teachers perceive and understand action research in terms of:

- 1.1.

- the processes of AR;

- 1.2.

- attitudes toward the conduct of AR;

- 1.3.

- principles in performing the AR?

“The teacher-researchers have vague or profound ideas. The intended improvements of the studies were not clear. They need to determine what exactly do they want to happen, what they can do. Explain the interventions well. The resource speakers reiterated that psychological constructs like motivation and engagement cannot be measured in two weeks. At least, this should be four weeks. Cognitive constructs like achievement, understanding is doable or measurable in one or two weeks although this can only pertain to certain competencies.” RON

“The processes involved in action research may be tedious, but they help you clarify the direction you need to take toward the completion of your study. The mapping out of your action plan, the writing of research statements, the writing of the research title, abstract, and key words allow you, as researcher, to organize your thoughts and help you focus on what to prioritize, to retrace your steps, and rethink about your plan.” (RJ)

“They were volunteers despite knowing that STAR will be an additional load on their end. They know it will be held on nine (9) Saturdays with three (3) hours per session. They were fully aware that they might be going to work hard, and this will be an added task. However, they seemed to be ready. The group seemed to be excited with the tasks ahead of them. Perhaps because they were really research enthusiasts. As the sessions progressed, the participants were engaged. Exchanges in Hangouts were constant about what, how to do things. Participants shared resources, ideas, asked for advice, shared their joys like when a tool was approved by certain authors. Every time the session ends, the researcher received affirmations and gratitude notes.”

3.11. Research Question 2

- 2.

- Is there a significant difference to the teachers’ perception and understanding of action research before and after the training?

3.12. Research Question 3

- 3.

- How do the teachers perceive technology integration in terms of:

- 3.1.

- their proficiency on the use of hardware and software,

- 3.2.

- the factors that influence their adoption and integration of technology in teaching,

- 3.3.

- their concerns on technology integration in education?

3.13. Research Question 4

- 4.

- How can the institution sustain the teachers desired level of research excellence?

- (1)

- Would you recommend the STAR program to others?

- (2)

- What drives you to conduct research?

- (3)

- What support do you need to conduct your study?

3.14. Research Question 6

- 5.

- What is the effect of the use of web video conferencing on the conduct of STAR program as a model toward teacher leadership and academic vitality?

4. Discussions

- 1.

- The use of web video conferencing to deliver the program efficiently and effectively in a remote learning environment.

- 2.

- The nature of the workshop program

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gladović, P.; Deretić, N.; Drašković, D. Video Conferencing and Its Application in Education. Traffic Transp. Theory Pract. 2020, 5, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales-Zamora, J.A.; Alave, J.; De Lima-Corvino, D.F.; Fernandez, A. Videoconferences of infectious diseases: An educational tool that transcends borders. A useful tool also for the current COVID-19 pandemic. Infez Med. 2020, 28, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Almarzooq, Z.I.; Lopes, M.; Kochar, A. Virtual learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: A disruptive technology in graduate medical education. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 2635–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatani, T.H. Student satisfaction with videoconferencing teaching quality during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, R.K.; Boaler, J.; Dieckmann, J.A. Achieving Elusive Teacher Change through Challenging Myths about Learning: A Blended Approach. Educ. Sci. 2018, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garet, M.S.; Porter, A.C.; Desimone, L.; Birman, B.F.; Yoon, K.S. What makes professional development effective? Results from a national sample of teachers. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2001, 38, 915–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Little, J.W. Assessing the prospects for teacher leadership. In Building a Professional Culture in Schools; Lieberman, A., Ed.; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988; pp. 78–106. [Google Scholar]

- Republic Act No. 10912, Continuing Professional Development (CPD) Act of 2016. Available online: https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/2016/07/21/republic-act-no-10912/ (accessed on 20 March 2019).

- York-Barr, J.; Duke, K. What do we know about teacher leadership? Findings from two decades of scholarship. Rev. Educ. Res. 2004, 74, 255–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, B.; Ginsberg, R. Creating lead teachers: From policy to implementation. Phi Delta Kappan 1990, 71, 616–621. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Education (2016). Order No.39 s.2016. Available online: http://www.deped.gov.ph/2016/06/10/do-39-s-2016-adoption-of-the-basic-education-research-agenda/2 (accessed on 7 March 2020).

- Murphey, J. Connecting Teacher Leadership and School Improvement; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hardre, P. Raising the bar on faculty productivity: Realigning performance standards to enhance quality trajectories. J. Fac. Dev. 2014, 28, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Wolkenhauer, R.M.; Hill, A.P.; Dana, N.F.; Stukey, M. Exploring the Connections Between Action Research and Teacher Leadership: A Reflection on Teacher-Leader Research for Confronting New Challenges. New Educ. 2017, 13, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koşar, D.; Kılınç, A.C.; Koşar, S.; Er, E.; Öğdem, Z. The relationship between teachers’ perceptions of organizational culture and school capacity for change [Öğretmenlerin örgüt kültürü ile değίim kapasitesi algılaand treatments to medical stı arasığlařarašndakiiliški]. Eğitim Bilimleri Araştırmaları Derg.—J. Educ. Sci. Res. 2016, 6, 39–59. [Google Scholar]

- Schein, E.H. Organizational Culture and Leadership, 2nd ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cansoy, R.; Parlar, H. Examining the relationship between school culture and teacher leadership. Int. Online J. Educ. Sci. 2017, 9, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenner, J.A.; Campbell, T. The theoretical and empirical basis of teacher leadership: A review of the literature. Rev. Educ. Res. 2016, 87, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Finster, M. Teacher Leadership Program Readiness Surveys, Toolkit/Guide. Teacher and Leadership Programs. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED573892.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2019).

- Torrato, J.B.; Aguja, S.E.; Prudente, M.S. Assessing Teacher Leadership Readiness during the Pandemic. In Proceedings of the IEEE 2021: International Conference on Educational Technology, Beijing, China, 18–20 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, M.L.; Johnson, S.M.; Kirkpatrick, C.L.; Marinell, W.; Steele, J.L.; Szczesiul, S.A. Angling for access, bartering for change: How second-stage teachers experience differentiated roles in schools. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2005, 110, 1088–1114. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran-Smith, M.; Lytle, S.L. Inside/Outside: Teacher Research and Knowledge; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran-Smith, M.; Lytle, S.L. Inquiry as Stance: Practitioner Research for the Next Generation; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Webber, K.L. Factors related to faculty research productivity and implications for academic planners. Plan. High. Educ. 2011, 39, 32–43. [Google Scholar]

- Osterling, K.L.; Austin, M.J. The Dissemination and Utilization of Research for Promoting Evidenced-Based Practice. J. Evid.-Based Soc. Work 2008, 5, 295–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basic Governance Act of 2011. Republic Act No. 9155. Available online: https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/2001/08/11/republic-act-no-9155/ (accessed on 18 June 2019).

- Kauffmann, P.; Unal, R.; Fernandez, A. and Keating, C. A model for allocating resources to research programs by evaluating technical importance and research productivity. Eng. Manag. J. 2000, 12, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustaining Research Productivity throughout an Academic Career: Recommendations for an Integrated and Comprehensive Approach. Available online: http://cms-content.bates.edu/prebuilt/chem-vitalfaculty.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2018).

- Atay, D. Teachers’ professional development: Partnership in research. Electron. J. Engl. A Second. Lang. 2006, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Dana, N.F.; Yendol Hoppey, D.; Yendol Silva, D. The Reflective Educator’s Guide to Classroom Research: Learning to Teach and Teaching to Learn through Practitioner Inquiry, 2nd ed.; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. Available online: http://www.loc.gov/catdir/toc/ecip0810/2008004886.html (accessed on 20 March 2019).

- Darling-Hammond, L. Teacher education around the world: What can we learn from international practice? Eur. J. Educ. 2017, 40, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber-Main, A.M.; Finstad, D.A.; Center, B.A.; Bland, C.J. An adaptive approach to facilitating research productivity in a Primary Care Clinical Department. Acad. Med. 2013, 88, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brydon-Miller; Prudente, M.S.; Aguja, S.E. Educational Action Research a Transformative Practice. In The BERA/SAGE Handbook of Educational Research; British Educational Research Association & Sage Reference: London, UK, 2017; Chapter 21. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, K.A.; Greene, C.H.; Anderson, P.J. Action Research: A Tool for Improving Teacher Quality and Classroom Practice; Ontario Action Researcher: Ontario, ON, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hine, G.S.C.; Lavery, S.D. Action Research: Informing Professional Practice within Schools. Issues Educ. Res. 2014, 24, 162–173. Available online: http://www.iier.org.au/iier24/hine.html (accessed on 12 March 2019).

- Zeichner, K.M. Teacher research as professional development for K–12 educators in the USA. Educ. Action Res. 2003, 11, 301–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asrat, D.; Aster, A. Teachers’ perception toward quality of education and their practice: The case of Codar Secondary School Ethopia. Am. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 4, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulla, M.B.; Barrera, K.B.; Acompanado, M.M. Philippine classroom teachers as researchers: Teacher’s perceptions, motivations, and challenges. Aust. J. Educ. 2017, 42, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teacher Research and Action Research. Available online: http://www.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-binaries/43590_12.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2019).

- World Bank Group. Learning Recovery after COVID-19 in Europe and Central Asia Policy and Practice: Policy and Practice; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- OECD and Joint Research Centre—European Commission. Assessing the Effects of ICT in Education: Indicators, Criteria and Benchmarks for International Comparisons; Joint Research Centre—European Commission: Luxembourg, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dexter, S. School technology leadership: Artifacts in systems of practice. J. Sch. Leadersh. 2011, 21, 166–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.E.; Maninger, R.M. Preservice teachers’ abilities, beliefs, an intention regarding technology integration. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2007, 37, 151–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, Y.G.; Jong, J.; Kim, H. What makes teachers use technology in the classroom? Exploring the factors affecting facilitation of technology with a Korean sample. Comput. Educ. 2008, 50, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, D.A.; Baran, E.; Thompson, A.D.; Mishra, P.; Koehler, M.J.; Shin, T.S. Technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) the development and validation of an assessment instrument for preservice teachers. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2009, 42, 123–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uygur, M.; Ayçiçek, B.; Doğrul, H.; Yanpar Yelken, T. Investigating Stakeholders’ Views on Technology Integration: The Role of Educational Leadership for Sustainable Inclusive Education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, K.A.A.; Wijesuriya, D.I.; Ekanayake, S.Y.; Rennie, A.E.W.; Lambert, C.G.; Gunawardhana, N. Online Delivery of Teaching and Laboratory Practices: Continuity of University Programmes during COVID-19 Pandemic. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, D.K. Medical students’ perceptions and an anatomy teacher’s personal experience using an e-learning platform for tutorials during the covid-19 crisis. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2020, 13, 318–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlanga, D.; Moloi, T. COVID-19 and the Digital Transformation of Education: What Are We Learning on 4IR in South Africa? Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuval, N.H. Home Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow; Vinate: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yuval, N.H. 21 Lessons for the 21st Century; Jonathan Cape: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Groff, J. Technology-Rich Innovative Learning Environment; Report on OECD CERI Innovative Learning Environment Project; CECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO 2014 Asia-Pacific Education Research Institutes Network (ERI-Net). Regional Study on Transversal Competencies in Education Policy & Practice (Phase II, School and Teaching Practices for Twenty-First Century Challenges: Lessons from the Asia Pacific Region); UNESCO: Bangkok, Thailand, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Care, J.; Kim, H.; Vista, A. Assessment of Transversal Competencies: Current Tools in the Asian Region; UNESCO: Bangkok, Thailand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, B.; Friesen, S.; Beck, J.; Roberts, V. Supporting New Teachers as Designers of Learning. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascio, W.F.; Montealegre, R. How technology is changing work and organizations. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2016, 3, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almekhlafi, A.G.; Almeqdadi, F.A. Teacher’s Perceptions of Technology Integration in the United Arab Emirates School Classrooms. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2010, 13, 165–175. [Google Scholar]

- Altun, D.; Tantekin-Erden, F. Digital profiles of pre-service preschool teachers. In Proceedings of the 17th International Primary Teaching Education Symposium, Ankara, Turkey, 11–14 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vrasidas, C.; Glass, G. Achieving technology integration in classroom teaching. In Current Perspectives in Applied Information Technologies: Preparing Teachers to Teach with Technology; Vrasidas, C., Glass, G.V., Eds.; Information Age Publishing, Inc.: Greenwich, CT, USA, 2005; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, M.P.E.; Abulon, E.L.R.; Roxas-Soriano, P.; David, A.P.; Hermosisima, V.H.; Gerundio, M. Examining teachers’ conception of and needs on action research. Issues Educ. Res. 2016, 26, 464–489. Available online: http://www.iier.org.au/iier26/morales-2pdf (accessed on 5 February 2019).

- Scherer, R.; Tondeur, J.; Siddiq, F.; Baran, E. The importance of attitudes toward technology for pre-service teachers’ technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge: Comparing structural equation modeling approaches. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 80, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garrison, D.R.; Arbaugh, J.B. Researching the community of inquiry framework: Review, issues, and future directions. Int. Higher Educ. 2007, 10, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, O. Community of Inquiry and Video in Higher Education: Engaging Students Online. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED556456 (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Huang, W.J. Be visible in the invisible learning context: How can instructors humanize online learning. In Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Federation of Business Disciplines, Association of Business Information Systems (ABIS) Conference, Houston, TX, USA, 11–14 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, J.C.; Swan, K. Examining social presence in online courses in relation to students’ perceived learning and satisfaction. Online Learn. J. 2019, 7, 68–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garrison, D.R. E-Learning in the 21st Century: A Community of Inquiry Framework for Research and Practice, 3rd ed.; Routledge; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.; Hurt, A.; Richardson, J.C.; Swan, K.; Caskurlu, S. Community of Inquiry (COI) Framework; Purdue University: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison, D.R.; Anderson, T.; Archer, W. Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. Internet High. Educ. 2000, 2, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghavifekr, S.; Rosdy, W.A.W. Teaching and learning with technology: Effectiveness of ICT integration in schools. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2015, 1, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 2nd Edition; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Traditions; Sage Publication: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Miller, D. Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory Pract. 2002, 39, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V.; Terry, G.; Hayfield, N. Thematic analysis. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health and Social Sciences; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2006; pp. 843–860. [Google Scholar]

- Prudente, M.S.; Aguja, S.E. Principles, attitudes, and processes in doing action research: Perceptions of teachers from the Philippines. Am. Sci. Princ. 2017, 24, 8007–8011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrato, J.B.; Prudente, M.S.; Aguja, S.E. Technology Integration, Proficiency and Attitude: Perspectives from Grade School Teachers. In Proceedings of the 2020 11th International Conference on E-Education, E-Business, E-Management, and E-Learning, Osaka, Japan, 10–12 January 2020; pp. 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlander, E.W.; Arshan, N.; Zhou, S.; Goldenberg, C. Lifewide or School-Only Learning: Approaches to addressing the developing world’s learning crisis. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2019, 56, 333–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, S.B.; Tisdell, E.J. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design Implementation, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Teddlie, C.; Tashakkori, A. Foundations of Mixed Methods Research: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches in the Social and Behavioral Sciences; Sage Publication: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fetters, M. The Mixed Methods Research Workbook: Activities for Designing, Implementing, and Publishing Projects, 1st ed.; Mixed Methods Research Series; Sage Publication: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Torrato, J.B.; Aguja, S.E.; Prudente, M.S. Analysis of the Teachers’ Perceptions and Understanding on the Conduct of Action Research. In Proceedings of the 2021 12th International Conference on E-Education, E-Business, E-Management, and E-Learning, Tokyo, Japan, 10–13 January 2021; pp. 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. The Psychology of Attitudes; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich: Fort Worth, TX, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Glasman, L.R.; Albarracin, D. Forming attitudes that predict future behavior: A meta-analysis of the attitude- behavior relation. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 778–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maio, G.R.; Haddock, G.; Verplanken, B. The Psychology of Attitudes and Attitude Change; Sage Publication: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Continuity of Learning Plan; De La Salle Santiago Zobel School: Manila, Philippines, 2020; unpublished.

- De Guzman, C. Next Generation Blended Learning Program; De La Salle Santiago Zobel School: Manila, Philippines, 2015; unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Curriculum Framework; De La Salle Santiago Zobel School: Manila, Philippines, 2016; unpublished.

- International Society for Technology in Education. National Education Technology Standards for Administrators. Available online: http://www.iste.org/docs/pdfs/nets-a-standards.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2019).

- International Society for Technology in Education. ISTE Standards Administrators. Available online: http://www.iste.org/standard (accessed on 7 September 2019).

- Kusano, K.; Frederiksen, S.; Jones, L.; Kobayashi, M.; Mukoyama, Y. The effects of ICT environment on teachers’ attitudes and technology integration in Japan and the U.S. J. Technol. Educ. Innov. Pract. 2013, 12, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thannimalai, R.; Raman, A. Principals’ Technology Leadership and Teachers’ Technology Integration in the 21st Century Classroom. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 9, 177–187. Available online: http://www.iaeme.com/IJCIET/issues.asp?JType=IJCIET&VType=9&IType=2 (accessed on 7 September 2019).

- Torrato, J.B.; Prudente, M.S.; Aguja, S.E. Examining School Administrators’ Technology Integration Leadership. Int. J. Learn. Teach. 2021, 7, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.C.; Arbaugh, J.B.; Cleveland-Innes, M.; Ice, P.; Swan, K.P.; Garrison, D.R. Using the Community of Inquiry framework to inform effective instructional design. In The Next Generation of Distance Education: Unconstrained Learning; Moller, L., Huett, J.B., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 95–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ngubane-Mokiwa, S.A.; Khoza, S.B. Using Community of Inquiry (CoI) to Facilitate the Design of a Holistic E-Learning Experience for Students with Visual Impairments. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinakou, E. An investigation of factors that contribute to student satisfaction from online courses: The example of an online accounting course. In Proceedings of the 2013 Fourth International Conference on E-learning “Best Practices in Management, Design and Development of E-courses: Standards of Excellence and Creativity”, Manama, Bahrain, 7–9 May 2013; pp. 462–468. [Google Scholar]

- Candarli, D.; Yuksel, H.G. Students’ perceptions of videoconferencing in the classrooms in higher education. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 47, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoesein, E.M. Using Mobile Technology and Online Support to Improve Language Teacher Professionalism. In Proceedings of the 2nd Global Conference on Linguistics and Foreign Language Teaching, LINELT 2014, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 11–13 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stiller, K.D.; Köster, A. Cognitive Loads and Training Success in a Video-Based Online Training Course. Open Psychol. J. 2017, 10, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hajhashemi, K.; Caltabiano, N.J.; Anderson, N.J. Lecturers’ perceptions and experience of integrating online videos in higher education. Aust. Educ. Comput. 2018, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, G.T. Chang, T.F. Evaluating the Use of an Online Video Training Program to Supplement a Graduate Course in Applied Behavior Analysis. Int. J. Online Pedagog. Course Des. 2019, 9, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Quantitative Data | Codes |

|---|---|

| Principles on Action Research Questionnaire | PARQ |

| Perceptions on Technology Integration and Training Proficiency and Pedagogical Practices Questionnaire | PTITPPP |

| Qualitative Data | |

| Reflection Journal | RJ |

| Sustaining Teacher Leadership and Academic Vitality through Research | STAR |

| STAR Program Evaluation | SPE |

| STAR Program Impression | SPI |

| Action Research Action Plan | ARAP |

| Action Research Matrix | ARMx |

| Action Research Abstract | ARA |

| Action Research Manuscript | ARMN |

| Google Chat Feedback | GCF |

| Gmail Feedback | GMF |

| Researcher Observation Notes | RON |

| Likert Scale | Interval | Response Description |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | 3.50 to 4.00 | Strongly Agree (SA) |

| 3 | 2.50 to 3.49 | Agree (A) |

| 2 | 1.50 to 2.49 | Disagree (D) |

| 1 | 1.00 to 1.49 | Strongly Disagree (SD) |

| Likert Scale | Interval | Response Description |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | 4.00 to 5.00 | Proficient |

| 4 | 3.00 to 3.99 | Somewhat Proficient |

| 3 | 2.00 to 2.99 | Uncertain |

| 2 | 1.50 to 2.00 | Somewhat Not Proficient |

| 1 | 1.00 to 1.49 | Not Proficient |

| Quantitative Data. | Qualitative Data | Meta-Inference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | Survey | M | SD | Cohen’s-d | ||

| Process | Pre Survey | 3.16 | 0.16 | d = 0.7206 The effect size is from medium to large. | Clear Action Plan | Complementary |

| Post Survey | 3.25 | 0.21 | ||||

| Attitude | Pre Survey | 3.11 | 0.35 | Passion and Productivity | Expansion | |

| Post Survey | 3.34 | 0.31 | ||||

| Principles | Pre Survey | 3.52 | 0.39 | Improvement Theory | Expansion | |

| Post Survey | 3.69 | 0.31 | ||||

| General Average | Pre Survey | 3.25 | 0.25 | Regular Program | Complementary | |

| Post Survey | 3.41 | 0.19 | ||||

| Code | Category | Theme Description | Generated Themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Researcher’s Practices | Articulates reflection | The action research is reflective of the researcher’s teaching practices | Self-reflection |

| Research Focus | Root cause of the problem | The questions are explicit and directed to the intended outcome of the study | Clear Action Plan |

| Assessment of Current Situation | Refers to the consistency of the research questions, instruments, research design, and data analysis. | ||

| Continuous Improvement | Iterative Process | Action research is a continuous improvement that aims to change and improve practices. | Cyclical |

| Address the Challenges | Innovation | Action research has proposed intervention, solution or program that intends to address existing issues, challenges in the classroom setting using varied techniques or tools. | Intervention |

| Code | Category | Theme Description | Generated Themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Work of love | Enjoy trying out new things | It takes great passion, determination, and love to be able to engage in the conduct of action research. | Passion |

| Challenging yet rewarding | It is a challenging endeavor but fulfilling and rewarding. | ||

| Tedious but gives clarity | Effective Teacher | The conduct of action research is taxing but it’s gives clarity to the purpose of the lesson and/or teaching | Efficacy |

| Stimulating and productive | Professional Knowledge maker | Action research stimulates the researcher’s ideas to become productive in the profession. | Productivity |

| Self-exploration and growth | Action research is a process that involves self-exploration and professional growth. | Professional Growth | |

| Learning Experience | Provision of Training | Opportunity to learn from the experts is a gratifying experience | Opportunity |

| Code | Category | Theme Description | Generated Themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Improvement | Change practices to bring out results | Improvement of research skills and educational practices | Improvement Theory |

| Theory to Practice | Understand the importance of action research in addressing concerns, issues, and problems in school | Fusion of theory and practice to address education issues | Improved Professional Practice |

| Inform Change | Action research is an effective way to evaluate teaching strategies and modalities used in the teaching-learning process | Evaluation of teaching strategies to contribute to the knowledge base | Evaluation of Practices |

| Within the Context of the Teacher | It is an opportunity to further improve the teaching-learning process using the lens of the teacher | Gauge effectiveness of interventions or innovations within the context of the teacher | Teacher Efficacy |

| CLUSTER | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | t | df | Sig. (2-Tailed) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| PROCESS | Before Training After Training | −0.08182 | 0.25886 | 0.04506 | −0.17361 | 0.00997 | −1.816 | 32 | 0.079 |

| ATTITUDE | Before Training After Training | −0.23030 | 0.46333 | 0.08066 | −0.39459 | −0.06601 | −2.855 | 32 | 0.007 |

| PRINCIPLES | Before Training After Training | −0.17515 | 0.41750 | 0.07268 | −0.32319 | −0.02711 | −2.410 | 32 | 0.022 |

| GENERAL AVERAGE | Before Training After Training | −0.16030 | 0.29757 | 0.05180 | −0.26582 | −0.05479 | −3.095 | 32 | 0.004 |

| Quantitative Data | Qualitative Findings | Meta-Inference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct | M | SD | I | Proficient in Hardware and Software “The teachers can easily navigate the different technology tools. They do not have queries on the technology apps. All throughout the webinar workshop, they were focused on the content. This is indicative that software and hardware are not major issues.” | Expansion The observation of the researcher on how the participants easily use the devices and navigate the technology applications during the workshop solidifies the positive perceptions on the use of hardware and software as seen in the mean score. |

| Hardware | 4.43 | 0.81 | P | ||

| Software | 4.27 | 0.99 | P | ||

| Construct | M | SD | I | Teaching Strategies “Technology allows self-paced learning, gamified activities, and asynchronous access to educational materials. Engagement is highly addressed, and self-evaluation is maintained and enforced.” “I believe it can become beneficial in improving my approach and techniques in teaching more effectively to my students and preparing efficiently my lesson.” | Expansion The participants reflections on how technology affects their teaching and students’ learning confirms their adoption and concerns on technology integration as evidenced by the mean scores. |

| Adoption of Technology | 3.51 | 0.83 | SA | ||

| Concerns/ Attitude | 3.23 | 0.93 | A | ||

|

| Code | Category | Description | Generated Theme |

|---|---|---|---|

| Research Department | Assign Research Coordinator and Consultant/s | Create digital research common where researchers and other Lasallian Partners can collaborate and engage in the conduct of research. This includes Research mentoring, Think Tank sessions, and critiquing to sustain and foster a culture of research within the institution | Research Office |

| Training | Send faculty and administrators to reputable research conferences | STAR becomes a regular training for all employees | Regular Training |

| Mentor | Regular follow through of research writers | Walkthrough or mentor interested and potential Lasallian researchers | Mentoring |

| Rewards | Give incentives, merit, or compensation | Give recognition or merit to acknowledge the contribution and/or efforts of employees | Meaningful Rewards |

| Research Repository | Online Research Journal | Create a repository of all research articles | Research Journal |

| Time | Balance time for teaching and writing | Give protected time for research writing | Balanced Time |

| Strongly Agree | Agree | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

| 95.5 | 4.5 | 0% | 0% |

| 95.5 | 4.5 | 0% | 0% |

| 95.5 | 4.5 | 0% | 0% |

| 9.1 | 90.9 | 0% | 0% |

| 86.4 | 13.6 | 0% | 0% |

| 0% | 0% | ||

| 100 | 0 | 0% | 0% |

| 90.9 | 9.1 | 0% | 0% |

| 100 | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| ||||

| 90.9 | 9.1 | 0% | 0% |

| 95.5 | 4.5 | 0% | 0% |

| 95.5 | 4.5 | 0% | 0% |

| What Did You Find Most Beneficial about the Program? | |

|---|---|

| CoI | Participant’s Evaluation |

| Teaching Presence |

|

| Cognitive Presence |

|

| Social Presence |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Torrato, J.B.; Aguja, S.E.; Prudente, M.S. Using Web Video Conferencing to Conduct a Program as a Proposed Model toward Teacher Leadership and Academic Vitality in the Philippines. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 658. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110658

Torrato JB, Aguja SE, Prudente MS. Using Web Video Conferencing to Conduct a Program as a Proposed Model toward Teacher Leadership and Academic Vitality in the Philippines. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(11):658. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110658

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorrato, Janette Biares, Socorro Echevarria Aguja, and Maricar Sison Prudente. 2021. "Using Web Video Conferencing to Conduct a Program as a Proposed Model toward Teacher Leadership and Academic Vitality in the Philippines" Education Sciences 11, no. 11: 658. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11110658