When Authenticity Goes Missing: How Monocultural Children’s Literature Is Silencing the Voices and Contributing to Invisibility of Children from Minority Backgrounds

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Children’s Literature to Support Principles of Diversity

1.2. Defining Diversity in the Context of This Paper

1.3. The Australian Context

1.4. Challenges in Addressing and Responding to Diversity

1.5. Investigating the Understandings and Practices of Educators

- What are educators’ understandings and beliefs of the role of children’s literature in supporting principles of diversity?

- How do educators select and use children’s literature to promote principles of diversity?

1.6. Ethics

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Context

2.2. Research Participants and Selection

2.3. Data Sources

- An audit of 2413 children’s books.

- 3 h and 35 min of recorded interviews with educators.

- 148 video recorded observations of book sharing sessions.

- 119 A4 pages of researcher’s handwritten field notes.

2.3.1. Book Audit

2.3.2. Interview Data

2.3.3. Book Sharing Data and Detailed Observation Spreadsheet

2.3.4. Field Notes

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

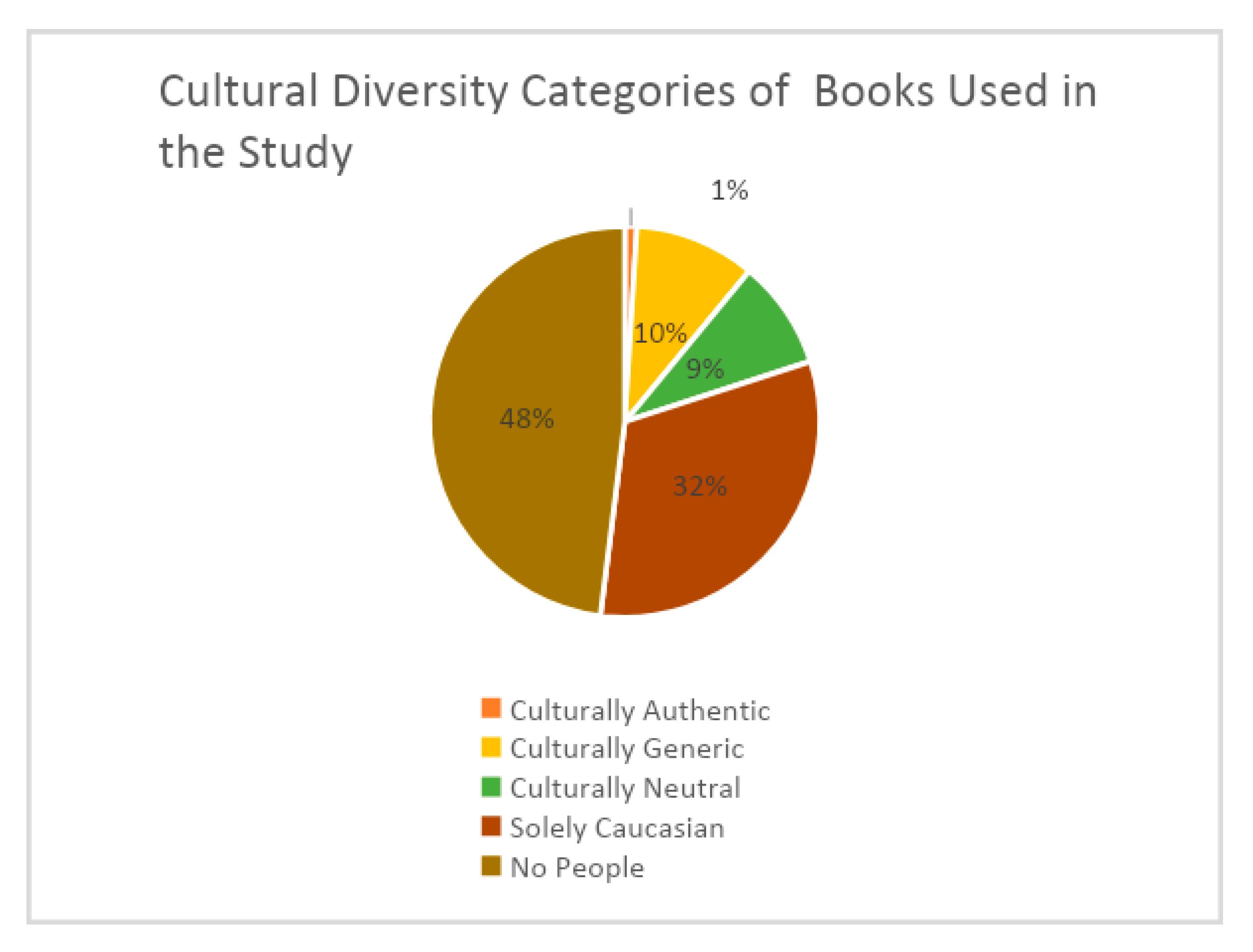

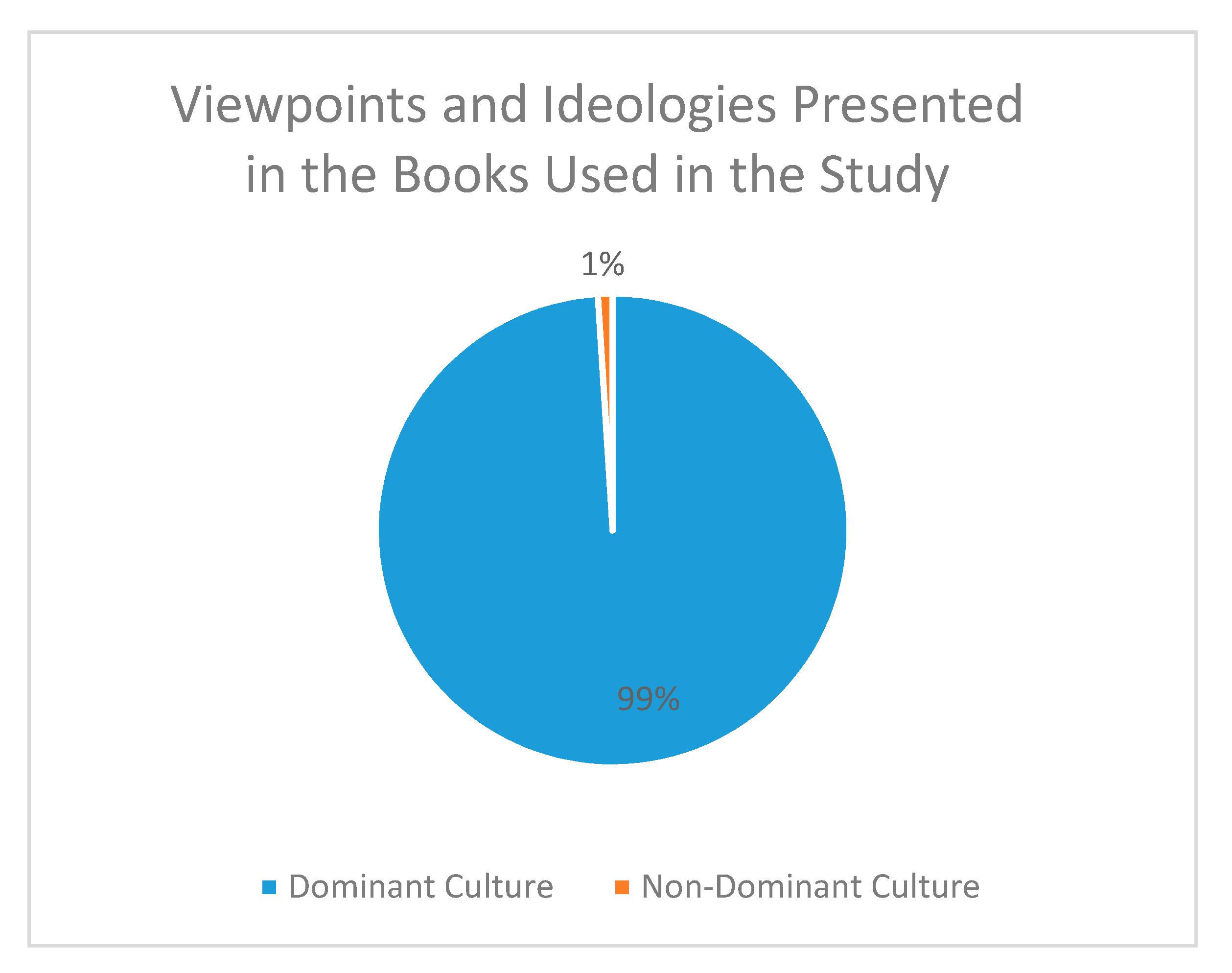

3.1. Limited Access to Books Portraying Inclusive and Authentic Cultural Diversity

3.2. Restricted Educator Understandings and Confidence

We are blessed in this Centre; we have so many different cultures attending this service that I mean to the children it’s just second nature to see someone that you know may look different or sound different to you know…have different ways about them and I think you know books that we purchase or could look at buying, would only support that.

3.3. Book Reading Practices: The “Othering” of Those from Minority Backgrounds

3.3.1. Book Sharing without Educator Attention to Diversity

3.3.2. Intentional Focus on Diversity

4. Summary

5. Conclusions

6. Recommendations

7. Limitations

8. Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bishop, R.S. Selecting literature for a multicultural curriculum. In Using Multi-Ethnic Literature in the K-8 Classroom; Harris, V.J., Ed.; Christopher-Gordon: Norwood, MA, USA, 1997; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hickling-Hudson, A. ‘White’, ‘Ethnic’ and ‘Indigenous’: Pre-service teachers reflect on discourses of ethnicity in Australian culture. Policy Futures Educ. 2005, 3, 340–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNaughton, G. Silences and sub-texts of immigrant and non-immigrant children. Child. Educ. 2001, 78, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, S. Affirming Diversity, 3rd ed.; Longman Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto, S. On Becoming Sociocultural Mediators. Teaching Works: Working Papers. Available online: http://www.teachingworks.org/images/files/TeachingWorks_Nieto.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2017).

- Sylva, K.; Siraj-Blatchford, I.; Taggart, B. Assessing Quality in the Early Years: Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale; Trentham Books Limited: Staffordshire, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Souto-Manning, M. Negotiating culturally responsive pedagogy through multicultural children’s literature: Towards critical democratic literacy practices in a first grade classroom. J. Early Child. Lit. 2009, 9, 50–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colby, S.A.; Lyon, A.F. Heightening awareness about the importance of using Multicultural literature. Multicult. Educ. 2004, 11, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, L.J.; Brand, S.T. More alike than different: Promoting respect through multicultural books and literacy strategies. Child. Educ. 2010, 86, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klefstad, J.M.; Martinez, K.C. Promoting Young Children’s Cultural Awareness and Appreciation through Multicultural Books. YC Young Child. 2013, 68, 74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, R.S. Multicultural literature for children: Making informed choices. In Teaching Multicultural Literature in Grades K-8; Harris, V.J., Ed.; Christopher-Gordon: Norwood, MA, USA, 1993; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, R.S. Reflections on the development of African American literature. J. Child. Lit. 2012, 38, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Boutte, G.S.; Hopkins, R.; Waklatsi, T. Perspectives, voices, and worldviews in frequently read children’s books. Early Educ. Dev. 2008, 19, 941–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koss, M.D.; Daniel, M.C. Valuing the Lives and Experiences of English Learners: Widening the Landscape of Children’s Literature. TESOL J. 2018, 9, 431–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowery, R.; Sabis-Burns, D. From borders to bridges: Making cross-cultural connections through multicultural literature. Multicult. Educ. 2007, 14, 50. [Google Scholar]

- Sims, R. Shadow and Substance: African-American Experience in Contemporary Children’s Fiction; National Council of Teachers of English: Urbana, IL, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Souto-Manning, M.; Rabadi-Raol, A.; Robinson, D.; Perez, A. What Stories Do My Classroom and Its Materials Tell? Preparing Early Childhood Teachers to Engage in Equitable and Inclusive Teaching. Young Except. Child. 2019, 22, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, H.; Barratt-Pugh, C.; Haig, Y. Book collections in long day care: Do they reflect racial diversity? Australas. J. Early Child. 2017, 42, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallworth, B.; Gibbons, L.; Fauber, L. It’s not on the list: An exploration of teacher perspectives on using multicultural literature. J. Adolesc. Adult Lit. 2006, 49, 478–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, H.; Barratt-Pugh, C. The Challenge of Monoculturalism—What books are educators sharing with children and what messages do they send? Aust. Educ. Res. 2020, 47, 815–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutte, G.S.; Lopez-Robertson, J.; Powers-Costello, E. Moving Beyond Colorblindness in Early Childhood Classrooms. Early Child. Educ. J. 2011, 39, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deakin University Definitions; Deakin University: Melbourne, Australia, 2019; Available online: http://www.deakin.edu.au/equity-diversity/definitions.php (accessed on 14 November 2019).

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. United Nations Human Rights; 1989; Available online: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CRC.aspx (accessed on 14 November 2019).

- Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority. Education and Care Services National Law and Regulations; 2012. Available online: https://www.acecqa.gov.au/nqf/national-law-regulations/national-regulations (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Department of Education Employment and Workplace Relations [DEEWR]. Belonging, Being and Becoming: The Early Years Learning Framework for Australia; Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations: Barton, Australia, 2009.

- Buchori, S.; Dobinson, T. Diversity in teaching and learning: Practitioners’ perspectives in a multicultural early childhood setting in Australia. Australas. J. Early Child. 2015, 40, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, K.H.; Jones-Diaz, C. Diversity and Difference in Early Childhood Education: Issues for Theory and Practice; Open University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Souto-Manning, M.; Mitchell, C.H. The role of action research in fostering culturally-responsive practices in a preschool classroom. Early Child. Educ. J. 2009, 37, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInerney, D.M. Teacher Attitudes to Multicultural Curriculum Development. Aust. J. Educ. 1987, 31, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amigo, M.F. Liminal but Competent: Latin American Migrant Children and School in Australia. Child Stud. Divers. Contexts 2012, 2, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Apfelbaum, E.P.; Norton, M.I.; Sommers, S.R. Racial Color Blindness: Emergence, Practice, and Implications. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 21, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.A.; Urland, G.R. Race and gender on the brain: Electrocortical measures of attention to the race and gender of multiply categorizable individuals. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 8, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Haim, Y.; Ziv, T.; Lamy, D.; Hodes, R.M. Nature and Nurture in Own-Race Face Processing. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 17, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schofield, J.W. The colourblind perspective in schools: Causes and consequences. In Multicultural Education: Issues and Perspectives; Banks, J.A., McGee, C.A., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 271–295. [Google Scholar]

- Beneke, M.R.; Cheatham, G.A. Race talk in preschool classrooms: Academic readiness and participation during shared-book reading. J. Early Child. Lit. 2019, 19, 107–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittingham, C.E.; Hoffman, E.B.; Rumenapp, J.C. “It ain’t ‘nah’ it’s ‘no’”: Preparing preschoolers for the language of school. J. Early Child. Lit. 2018, 18, 465–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.W. Empathy and cultural competence: Reflections from teachers of culturally diverse children. Beyond J. Young Child. 2005, 1–8. Available online: https://currikicdn.s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/resourcedocs/55c33b99d7b6c.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Mendoza, J.; Reese, D. Examining multicultural picture books for the early childhood classroom: Possibilities and pitfalls/Una inspeccion de libros ilustrados multiculturales para los programas de la ninez temprana: Posibilidades y peligros. Early Child. Res. Pract. 2001, 3, NA. [Google Scholar]

- Blakeney-Williams, M.; Daly, N. How do teachers use picture books to draw on the cultural and linguistic diversity in their classroom? Set 2013, 2, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotty, M. The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process; Allen & Unwin: St. Leonards, Australia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Snape, D.; Spencer, L. The foundations of qualitative research. In Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers, 2nd ed.; Ritchie, J., Lewis, C., McNaughton, N., Ormston, R., Eds.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tharpe, R.G.; Gallimore, R. Rousing Minds to Life: Teaching, Learning, and Schooling in Social Context; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Community Profiles; 2011. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/censushome.nsf/home/communityprofiles?opendocument&navpos=230 (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Suri, H. Purposeful sampling in qualitative research synthesis. Qual. Res. J. 2011, 11, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, H.; Barratt-Pugh, C.; Haig, Y. “Portray cultures other than ours”: How children’s literature is being used to support the diversity goals of the Australian Early Years Learning Framework. Aust. Educ. Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.R. A General Inductive Approach for Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation Data. Am. J. Eval. 2006, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisp, T.; Knezek, S.M.; Quinn, M.; Bingham, G.E.; Girardeau, K.; Starks, F. What’s on our bookshelves? The diversity of children’s literature in early childhood classroom libraries. J. Child. Lit. 2016, 42, 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Borkfelt, S. Non-human Otherness: Animals as others and devices for Othering. In Otherness: A Mulitlateral Perspective; Sencindiver, S., Beville, Y.M., Laturtizen, M., Eds.; Peter Lang: Frankfurt, Germany, 2011; pp. 137–154. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, V.; Watson, D. Examining Whiteness in a Children’s Centre. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 2014, 15, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoorman, D. Reconceptualizing teacher education as a social justice undertaking. Child. Educ. 2011, 87, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derman-Sparks, L. Anti-Bias Curriculum: Tools for Empowering Young Children; National Association for the Education of Young Children: Washington, DC, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- David, R.G. Representing the Inuit in contemporary British and Canadian juvenile non-fiction. Child. Lit. Educ. 2001, 32, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.; Dean, E.; Holland, M. Contemporary American Indian cultures in children’s picture books. Young Child. Web 2005. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Contemporary-American-Indian-Cultures-in-Children%27s-Roberts-Dean/80731f014c85db8611e30d9177a37bba0216be33 (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Zeegers, M.; Muir, W.; Lin, Z. The primacy of the mother tongue: Aboriginal literacy and non-standard English. Aust. J. Indig. Educ. 2003, 32, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeegers, M. Positioning the school in the landscape: Exploring Black history with a regional Australian primary school. Discourse 2011, 32, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlke, E.; Bigler, R.S.; Suizzo, M.A. Relations between colorblind socialization and children’s racial bias: Evidence from European American mothers and their preschool children. Child Dev. 2012, 83, 1164–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollnick, D.M.; Chin, P.C. Multicultural Education in a Pluralistic Society, 8th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Spina, S.U.; Tai, R.H. The Politics of Racial Identity: A pedagogy of invisibility. Educ. Res. 1998, 27, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WNDB. We Need Diverse Books Website. Available online: https://diversebooks.org/ (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Cultural Diversity Database. National Centre for Australian Children’s Literature. Available online: https://www.ncacl.org.au/resources/databases/welcome-to-the-ncacl-cultural-diversity-database/ (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Adam, H.; Barratt-Pugh, C. Book sharing with young children: A study of book sharing in four Australian long day care centres. J. Early Child. Lit. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ownership/Operation/Location Note: Pseudonyms Are Used for Centre Names | % High Income Household (Higher than $2000 per Week) | % Low Income Earners (Less than $600 a Week) | Overseas Born Population-% of Total Population | Speaks a Language Other Than English at Home-% of Total Population | % of Total Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples | Participant Role | Participant Pseudonym | Industry Experience | Time in This Centre | Highest Qualification | Other Qualification | Other Information | No. of Other Educators | No. of Child Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Riverview: Not for profit centre Western Suburb of Perth Metropolitan Area | 47.3% (Includes 13% > $4000) | 13% | 34% | 15.7% | 0.18% Below national percentage of overall pop (3%) | Centre Coordinator | Jill | 20–25 years | 9 years | Bachelor of Children’s Services | Diploma of Child Psychology | Also holds nursing qualificat-ion and Cert iv | 5 | 36 |

| Lead Educator Kindergar-ten Room | Michelle | 15–20 years | 2 years | Bachelor of Arts Early Childhood Education | N/A | Qualificat-ion gained in Ireland | ||||||||

| Community House Not for profit centre Northern suburbs of Perth Metropolitan Area Funded by WA Dept. of Local Govt. | 13.9% (Includes 0.7% > $4000) | 22.8% | 53% | 57% | 4.3% Above national percentage of overall pop (3%) | Centre Coordinator | Warren | 25–30 years | 6 months | Diploma of Leadership and Management | Associate Diploma of Child Services | Nil | 4 | 22 |

| Lead Educator Kindergar-ten Room | Lily | 0–5 years | 4 months | Honours Degree in Early Childhood Education | N/A | Qualifica-tion gained in Ireland | ||||||||

| Dockside Not for profit centre outer suburb of Perth Metropolitan Area | 17.6% (Includes 1.5% > $4000) | 30.7% | 40% | 9.8% | 1.4% Below national percentage of overall pop | Centre Coordinator | Tracy | 10–15 years | 2 years | Diploma of Children’s Services | Cert iii | Nil | 4 | 34 |

| Lead Educator Kindergar-ten Room | Alice | 0–5 years | 5 years | Diploma of Children’s Services | Cert iii | Working to BSc in Early Child-hood | ||||||||

| Argyle Not for profit centre remote north east of Western Australia | 33% (Includes 4.8% > $4000) | 10.5% | 15.8% | 11.6% | 25.8% Well above national percentage of overall pop (3%) | Centre Coordinator | Sarah | 30–35 years | 0–5 years | Diploma of Children’s Services | Cert iii | Nil | 3 (2 from local Abor-iginal langua-ge Centre and visited once in the observ-ation period). | 18 |

| Lead Educator Kindergar-ten Room | Debbie | 25–30 years | 5 months | Bachelor’s Degree in Early Childhood Education | Cert iii | Nil |

| Centre | Number Educator Sessions Overall | Number Focused on Diversity | % of Ed Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Riverview | 51 | 2 | 6% |

| Community House | 47 | 6 | 14% |

| Dockside | 29 | 3 | 7% |

| Argyle | 21 | 0 | 0% |

| Centre/Book | Nature of Session Focus | Pattern of Understanding | Cultural Diversity Category of Book | Number of Sessions | Time (mins) | % of over-all Ed Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Riverview/1 | special/other | 3 | Generic | 1 | 17.50 | |

| Riverview/2 | special/other | 3 | Generic | 1 | 9.00 | |

| TOTALS | 2 | 26.5 | 6 | |||

| Community/1 | special/other | 3 | Authentic | 1 | 9.00 | |

| Community/2 | Language | 2 | Authentic | 2 | 10.00 | |

| Community/3 | language | 2 | Authentic | 3 | 16.5 | |

| TOTALS | 6 | 25.5 | 14.5 | |||

| Dockside/1 | language | 2 | Generic | 1 | 3 | |

| Dockside/2 | special/other | 3 | Generic | 1 | 8.5 | |

| Dockside/3 | language | 3 | Generic | 1 | 9.5 | |

| TOTALS | 3 | 11.5 | 7 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adam, H. When Authenticity Goes Missing: How Monocultural Children’s Literature Is Silencing the Voices and Contributing to Invisibility of Children from Minority Backgrounds. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11010032

Adam H. When Authenticity Goes Missing: How Monocultural Children’s Literature Is Silencing the Voices and Contributing to Invisibility of Children from Minority Backgrounds. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(1):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11010032

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdam, Helen. 2021. "When Authenticity Goes Missing: How Monocultural Children’s Literature Is Silencing the Voices and Contributing to Invisibility of Children from Minority Backgrounds" Education Sciences 11, no. 1: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11010032

APA StyleAdam, H. (2021). When Authenticity Goes Missing: How Monocultural Children’s Literature Is Silencing the Voices and Contributing to Invisibility of Children from Minority Backgrounds. Education Sciences, 11(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11010032