The Quality of Autism Spectrum Disorder Diagnosis: Families’ Views

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Waiting for the Diagnosis

1.2. Diagnosis Verification

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context Description

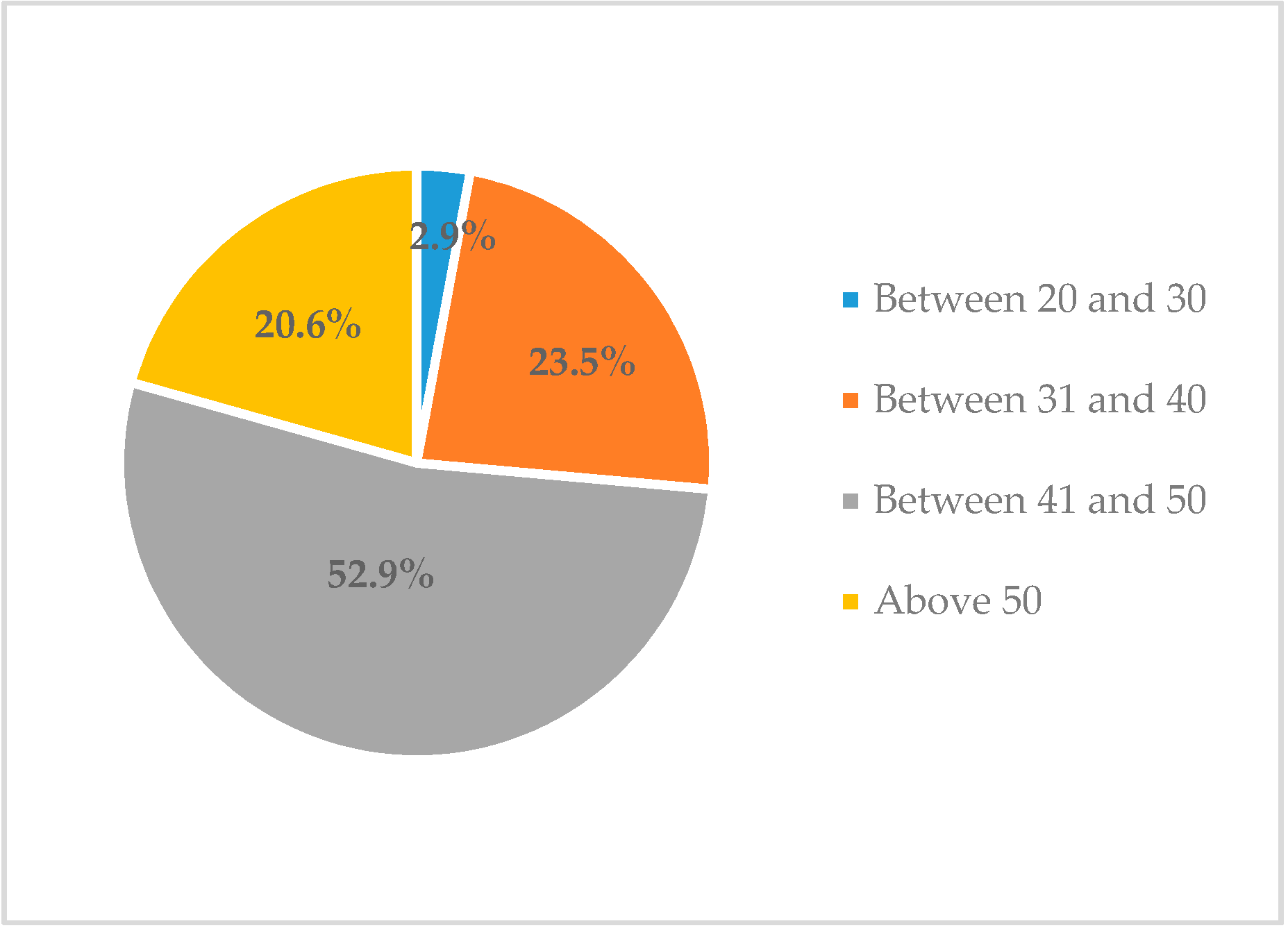

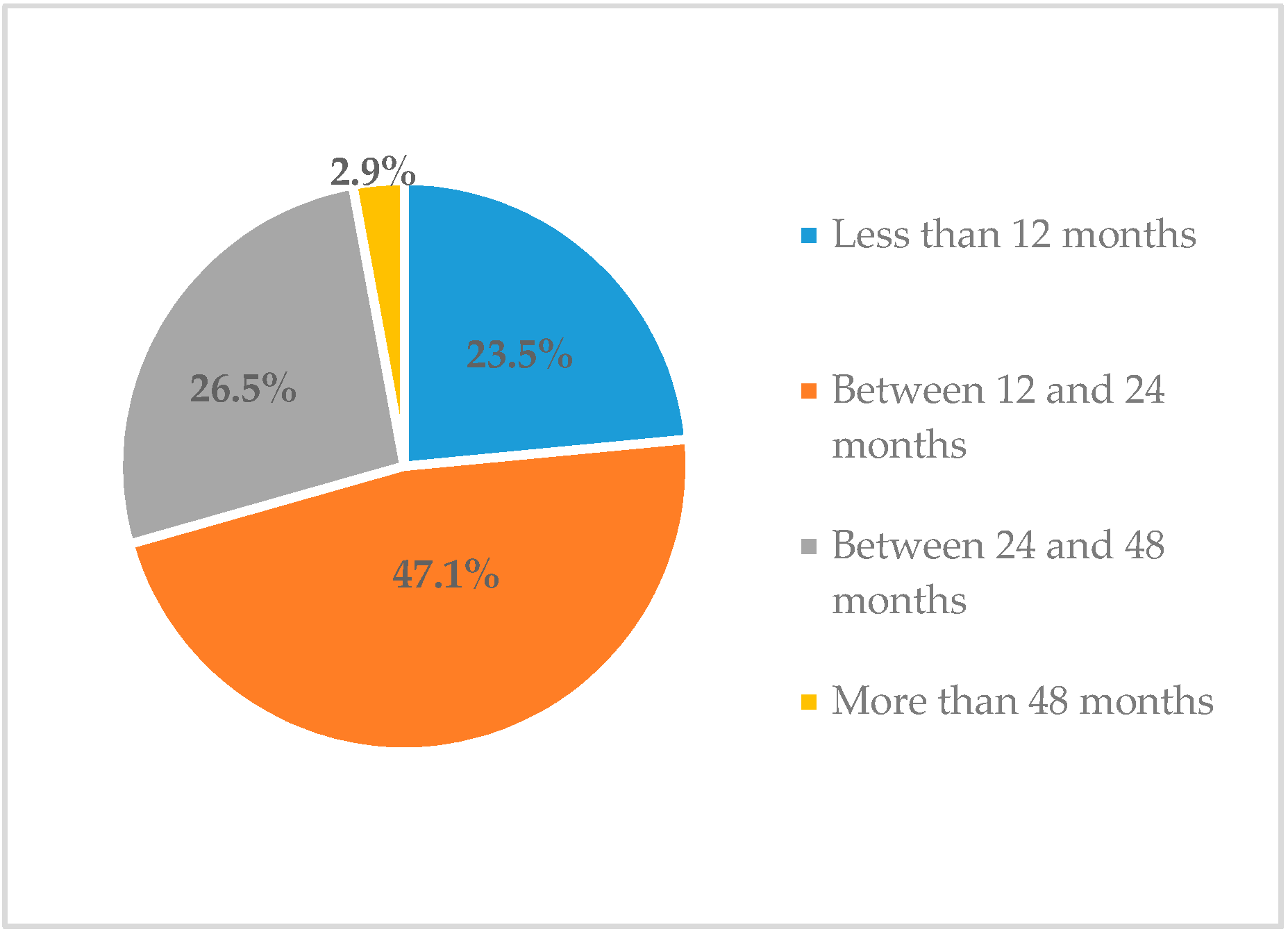

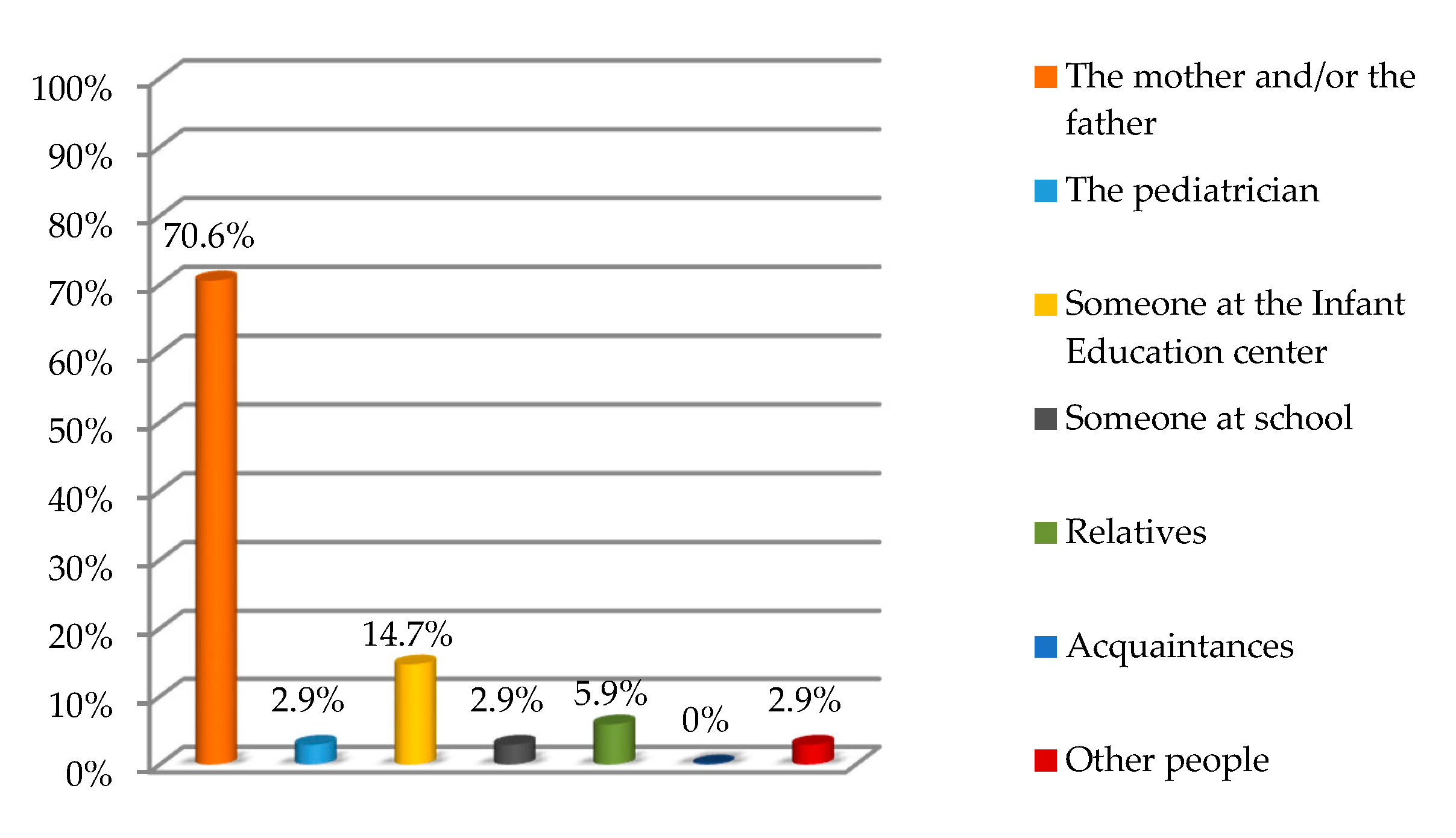

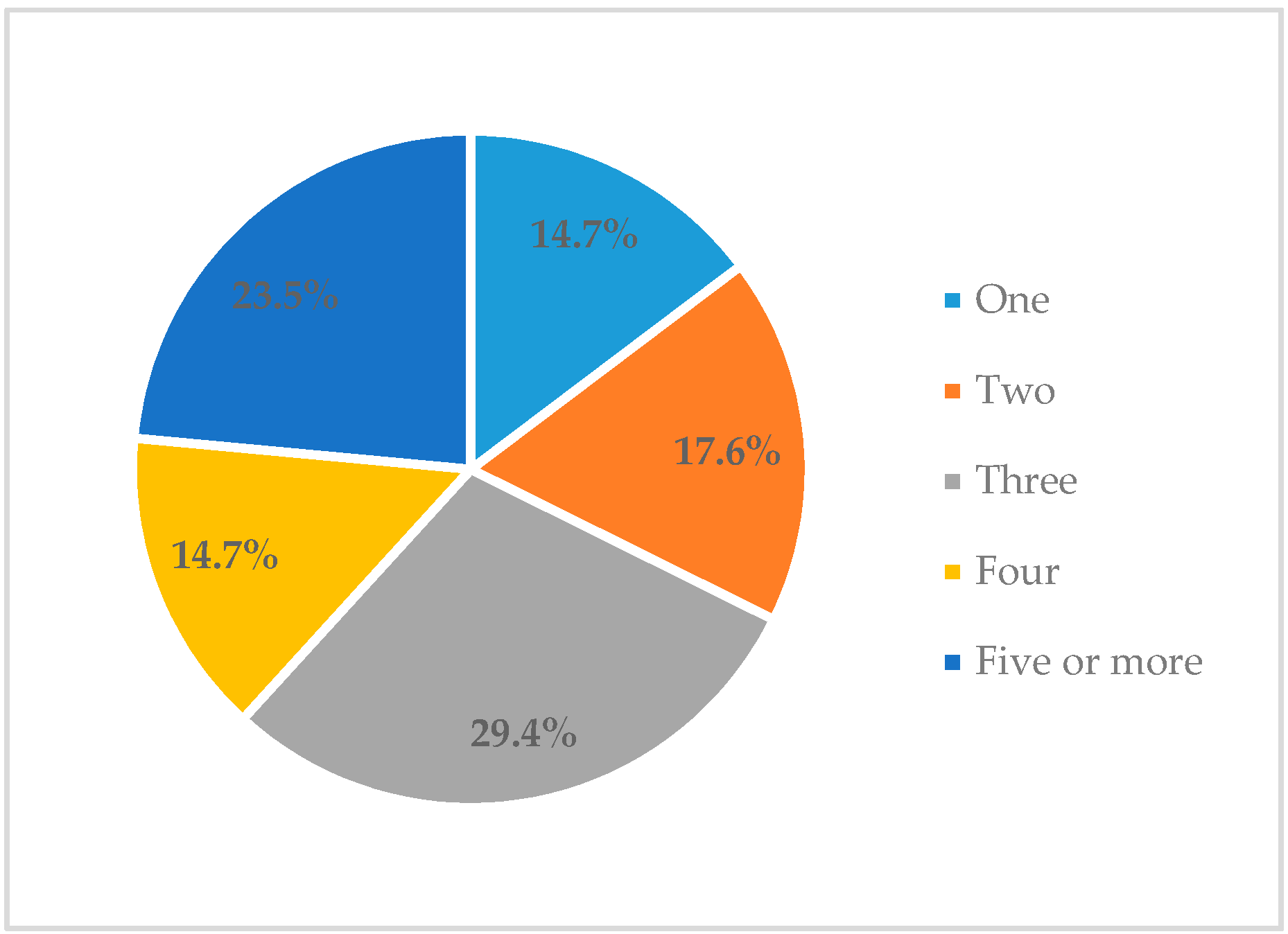

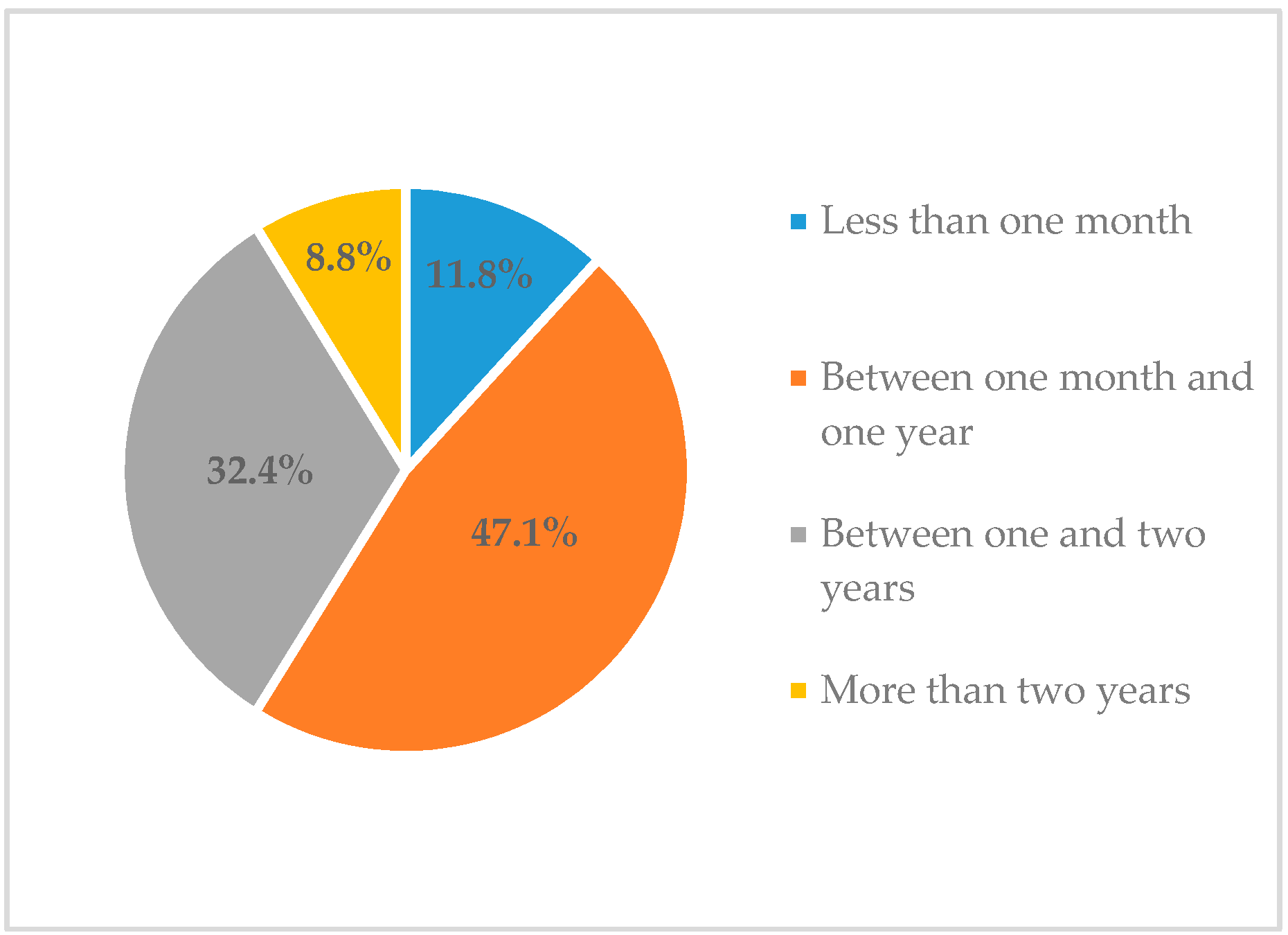

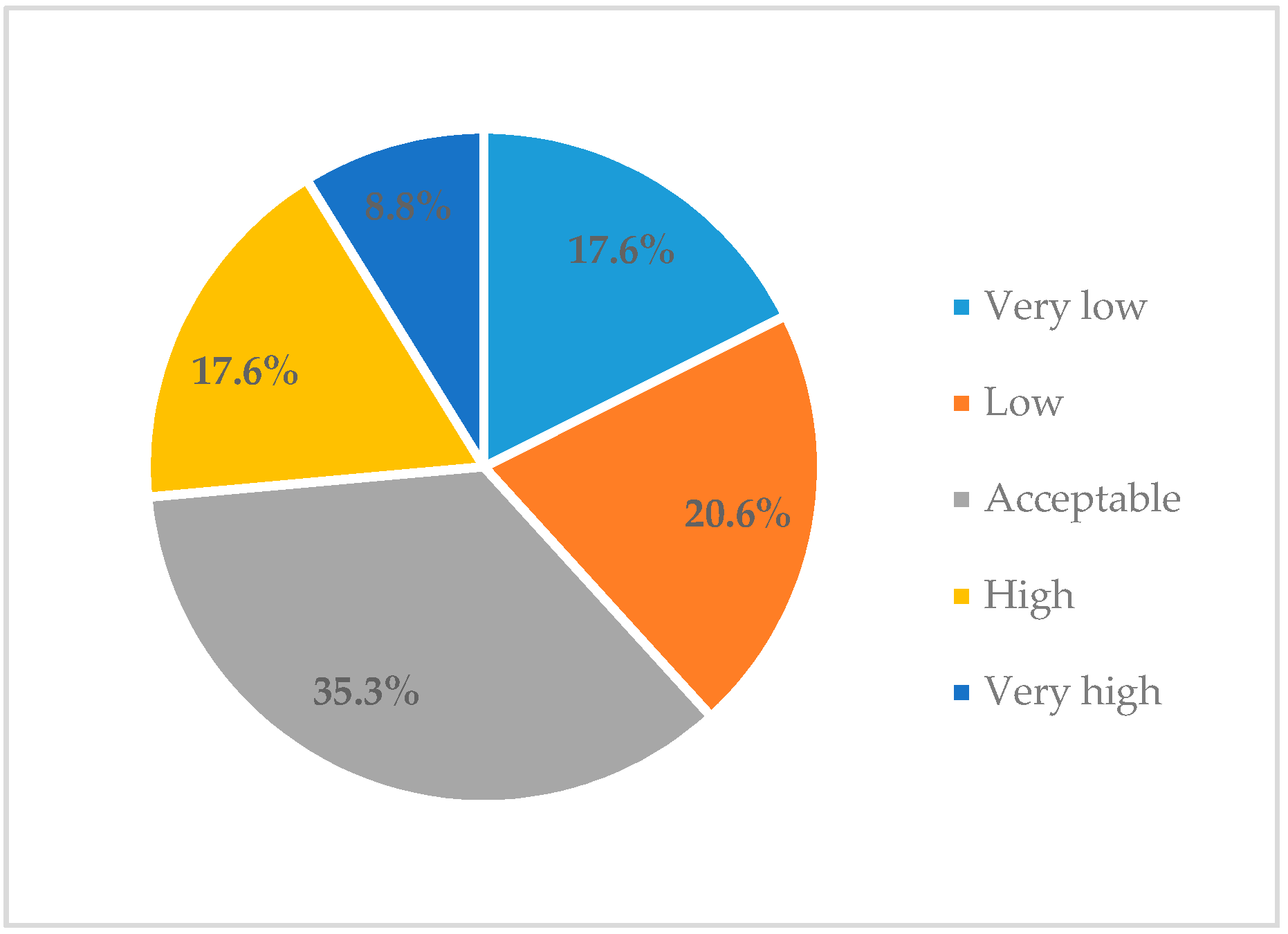

2.2. Sample Description

2.3. Tools

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

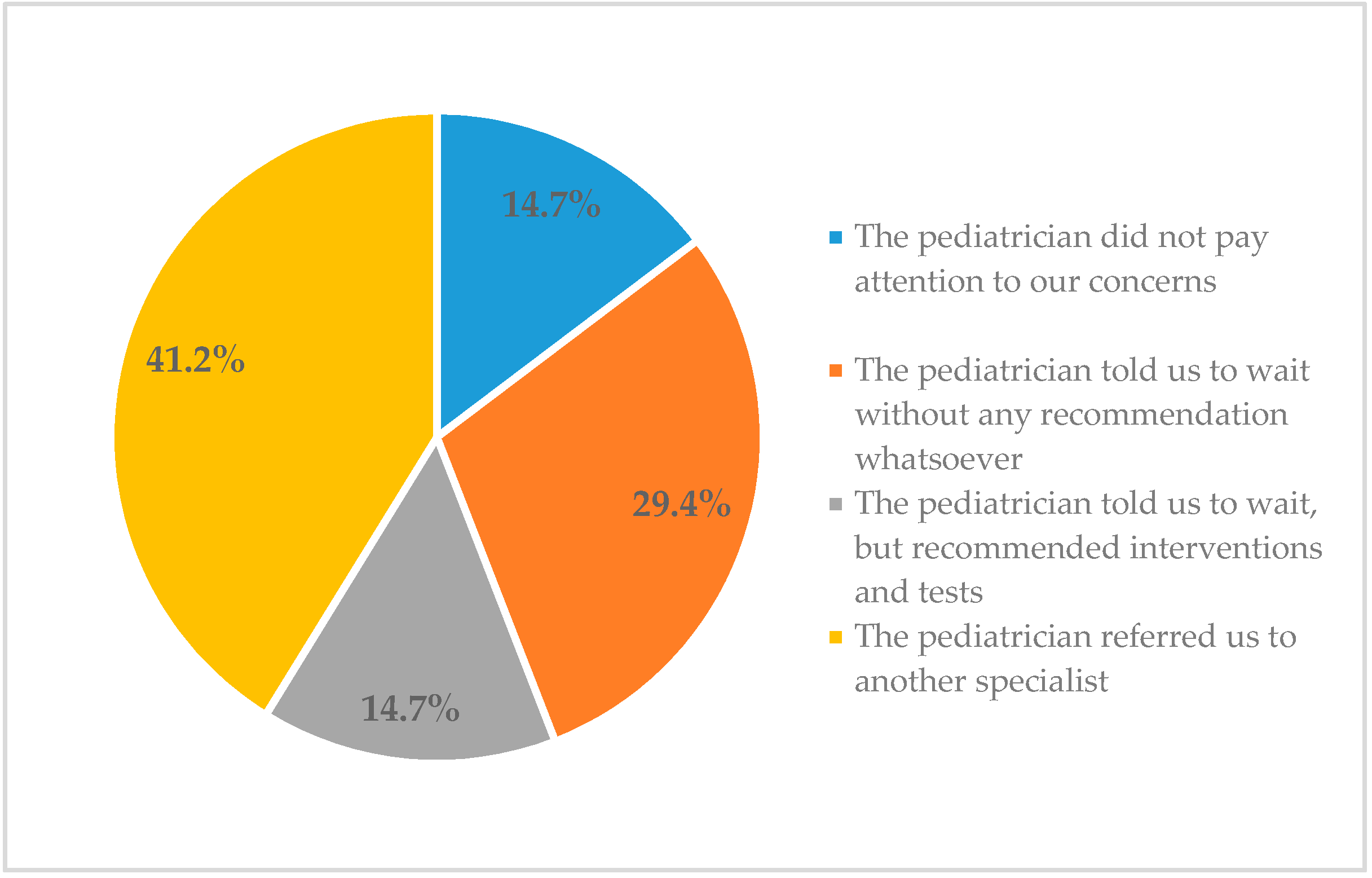

3.1. Quantitative Results

3.2. Qualitative Results

3.2.1. Families’ Experiences during the Pre-Diagnosis Stage

He was a lazy kid who slept a lot; he did better with the feeding bottle and, when he was awake, he laughed all the time and for whatever reason. He seemed to be completely normal until he was 2 years old. He said ‘mamá [mum],’ ‘tete’ [brother], ‘coche’ [car], ‘agua’ [water], ‘pan’ [bread] and so on, and then shortly after his second birthday, he stopped. He unlearnt what he had already learnt, it was as if he had forgotten it. It was then that I started to take action (Mother 3).

Neither pediatricians nor nurses detected any symptoms, it was only me who realized that there was something happening, and even my family told me there was nothing wrong with the child (Mother 2).

Being told by everyone that you see things that are not there is a real torture (Mother 4).

Besides, for a long time I had to put up with comments such as “the problem is that you don’t know how to raise your child” and others that make you feel that you are not a good mother and that it is your fault (Mother 1).

The diagnosis is a huge blow, but it is also a relief because then you finally get to know what is happening to your child. The months when you don’t know are the worst part (Mother 1).

The waiting time for diagnosis and treatment is appalling. Families go through a lot of stress and anxiety until they are finally seen (Mother 5).

There was a long time from when we first mentioned it until we were heard and referred to specialists (Mother 1).

There is a total lack of coordination between pediatricians, psychologists, and neuro-pediatricians. Each practitioner tries to solve the situation differently, which confuses parents even more (Mother 4).

It is very important to train pediatricians, family doctors, and health practitioners on how to treat children with ASD, since these professionals most often don’t know how to take the right course of action during consults (Mother 3).

The neuro-pediatrician confirmed the pediatrician’s suspicion and referred me to a non-profit association for diagnosis. Thanks to the orthopedic surgeon, who suggested an early care center that we could visit, we had a diagnosis and better care than that received from the neuro-pediatrician, who simply told us there was nothing else he could do (Mother 1).

My son was diagnosed privately, it cost me 400 euros; maybe that was why everything went faster and the psychologists who worked with him made greater efforts (Mother 2).

We obtained the diagnosis because we went to a specialist private practice after seeing that neither the school’s psychologist nor the neuro-pediatrician were able to give us any support, information or guidance, or an explanation about the disorder; nothing at all. They were poor professionals with zero empathy. The truth is that we have received everything from the specialist practice that we took our champ to (Mother 5).

3.2.2. Families’ Experiences in Relation to the Communication of the Diagnosis

He asked me to sit down and then straight away told me that they believed the problem was that my son had autism. And from then on, you don’t understand anything anymore, you just see Rain Man. It just threw me, this labelling stuff. Right after that, he said to me that my son would never know how to use a mobile, that he would be unable to speak, that he would not hug me or kiss me; and warned me to watch out, because 60% of couples who have children with autism end up separating; that he had plenty of books and information he could lend me, and so on and so forth. And at that moment I only wanted to go home, to run away from there. I found it hard to get into my car and drive home (Mother 3).

I felt there was a total lack of sensitivity. I wished they had told me that I should have gone with my husband or someone else. I disliked the way they conveyed the news to me. Just imagine, my husband phoned me, and I couldn’t even speak and explain to him what had happened; I just couldn’t do it (Mother 4).

Luckily, we were advised to see a psychologist who not only told us about the first steps to be taken and the places we needed to go to, but also spent a whole month observing my son and explaining to us what he should be able to do but couldn’t do (Mother 2).

Alongside the psychologist’s efforts and support, we were helped by an amazing social worker who, in spite of the initial uncertainty and shock, managed to guide us, told us which benefits to apply for, where to go and so on. She was extremely important at that moment (Mother 1).

The educational psychologist referred me to an association that did really good work, but I couldn’t bring myself to call them. I preferred to digest it first and, the truth is I found it very difficult. At that time, I didn’t know how to explain to people what was going on with my son. It is true that my parents and my parents-in-law knew where I was going and what for, but I felt incapable of telling other people (Mother 3).

I could hardly sleep more than one hour at night and took medications for months. At that time, you can’t understand what you have done for the world to treat you —and especially your child— like that (Mother 2).

3.2.3. Families’ Experiences during the Post-Diagnosis Stage

The first two years were very hard for the two of us as a couple, an abyss opened up between us. At first, we disappeared as a couple, we saw each other as strangers and each of us ruminated over the situation on our own. I had never argued with my husband until then and, at that time, we began to argue about everything. With the passing of time, we backed each other up and became close again; we stopped arguing, as we realized that we had a common goal, our son. You need to be ok so that your child can be ok too (Mother 5).

First, you must accept it yourself, and that is something you never do. Whoever says they do is lying, I think. You initially ask yourself, “why me?”, and eventually, you wonder, “why my son?” “What have we all done to deserve this?” You start to look for causes, whether it was vaccines, pollution, too little or too much weight, mercury, white fish, cement and in the end, as I always say, it’s your lot in life, it is down to your genes (Mother 3).

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- McConkey, R. The rise in the numbers of pupil identified by schools with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): A comparison of the four countries in the United Kingdom. Support Learn. 2020, 35, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Hidalgo, P.; Roigé-Castellví, J.; Hernández-Martínez, C.; Voltas, N.; Canals, J. Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among Spanish school-age children. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 3176–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narzisi, A.; Posada, M.; Barbieri, F.; Chericoni, N.; Ciuffolini, D.; Pinzino, M.; Romano, R.; Scattoni, M.L.; Tancredi, R.; Calderoni, S.; et al. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder in a large Italian catchment area: A school-based population study within the ASDEU project. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, S.; Lu, Y.; Li, Y.; Shi, J.; Cui, H.; Gu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhong, W.; Zhu, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder in Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 284, 112679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crane, L.; Batty, R.; Adeyinka, H.; Goddard, L.; Henry, L.A.; Hill, E.L. Autism diagnosis in the United Kingdom: Perspectives of autistic adults, parents and professionals. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2018, 48, 3761–3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estes, A.; Swain, D.M.; MacDuffie, K.E. The effects of early autism intervention on parents and family adaptive functioning. Pediatr. Med. 2019, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franz, L.; Dawson, G. Implementing early interventions for autism spectrum disorder: A global perspective. Pediatr. Med. 2019, 2, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaiz, P.; de Haro-Rodríguez, R.; Maldonado, R.M. Barriers to student learning and participation in an inclusive school as perceived by future education professionals. J. New Approach Edu. Res. 2019, 8, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matson, J.L.; Konst, M.J. Early intervention for autism: Who provides treatment and in what settings. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2014, 8, 1585–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilaseca, R.M.; Galván-Bovaira, M.J.; González-del-Yerro, A.; Baqués, N.; Oliveira, C.; Simó-Pinatella, D.; Giné, C. Training needs of professionals and the family-centered approach in Spain. J. Early Interv. 2019, 41, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConkey, R.; Cassin, M.T.; McNaughton, R. Promoting the social inclusion of children with ASD: A family-centered intervention. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gràcia, M.; Simón, C.; Salvador-Beltrán, F.; Adam, A.L.; Mas, J.M.; Giné, C.; Dalmau, M. The transition process from center-based programmes to family-centered practices in Spain: A multiple case study. Early Child Dev. Care 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legg, H.; Tickle, A. UK parents’ experiences of their child receiving a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review of the qualitative evidence. Autism 2019, 23, 1897–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russa, M.B.; Matthews, A.L.; Owen-DeSchryver, J.S. Expanding supports to improve the lives of families of children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Posit. Behav. Inter. 2015, 17, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmeggiani, A.; Corinaldesi, A.; Posar, A. Early features of autism spectrum disorder: A cross-sectional study. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2019, 45, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xavier, J.S.; Marchiori, T.; Schwartzman, J.S. Parents seeking a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder for their child. Psicol. Teor. Prat. 2019, 21, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, M.; Anagnostou, E.; Ungar, W.J. Practice patterns and determinants of wait time for autism spectrum disorder diagnosis in Canada. Mol. Autism 2018, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, K.Y.; Chang, H.L.; Chin, W.C.; Li, H.M.; Chen, S.H. How Taiwanese parents of children with autism spectrum disorder experience the process of obtaining a diagnosis: A descriptive phenomenological analysis. Autism 2018, 22, 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adib, N.A.N.; Ibrahim, M.I.; Rahman, A.B.; Bakar, R.S.; Yahaya, N.A.; Hussin, S.; Mansor, W.N.A.W. Predictors of caregivers’ satisfaction with the management of children with autism spectrum disorder: A study at multiple levels of health care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höfer, J.; Hoffmann, F.; Kamp-Becker, I.; Poustka, L.; Roessner, V.; Stroth, S.; Wolff, N.; Bachmann, C.J. Pathways to a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder in Germany: A survey of parents. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Ment. Health 2019, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, V.; Aldridge, F.; Sburlati, E.; Chandler, F.; Smith, K.; Cheng, L. Missed opportunities: An investigation of pathways to autism diagnosis in Australia. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2019, 57, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, V.; Yu, Y.; Keyes, M.L.; McGrew, J.H. Pre-diagnostic and diagnostic stages of autism spectrum disorder: A parent perspective. Child Care Pract. 2017, 23, 195–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicherman, N.; Loewenstein, G.; Tavassoli, T.; Buxbaum, J.D. Grandma knows best: Family structure and age of diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2018, 22, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boshoff, K.; Gibbs, D.; Phillips, R.L.; Wiles, L.; Porter, L. A meta-synthesis of how parents of children with autism describe their experience of advocating for their children during the process of diagnosis. Health Soc. Care Community 2018, 27, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, D.; Steyaert, J.; Dierickx, K.; Hens, K. Parents’ views and experiences of the autism spectrum disorder diagnosis of their young child: A longitudinal interview study. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nealy, C.E.; O’Hare, L.; Powers, J.D.; Swick, D.C. The impact of autism spectrum disorders on the family: A qualitative study of mothers’ perspective. J. Fam. Soc. Work 2012, 15, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, A.; Vaz, S.; Cordier, R.; Joosten, A.; Parsons, D.; Smith, C.; Falkmer, T. Factors associated with stress in families of children with autism spectrum disorder. Dev. Neurorehabil. 2017, 21, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valicenti-McDermott, M.; Lawson, K.; Hottinger, K.; Seijo, R.; Schechtman, M.; Shulman, L.; Shinnar, S. Parental stress in families of children with autism and other developmental disabilities. J. Child Neurol. 2015, 30, 1728–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K.; Chiang, H.M. Parenting stress in South Korean mothers of adolescent children with autism spectrum disorder. Int. J. Dev. Dis. 2018, 64, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, A.; Mira, A.; Berenguer, C.; Rosello, B.; Baixauli, I. Parenting stress in mothers of children with autism without intellectual disability. Mediation of behavioral problems and coping strategies. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paynter, J.; Davies, M.; Beamish, W. Recognising the “forgotten man”: Fathers’ experiences in caring for a young child with autism spectrum disorder. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2018, 43, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, P.R. Examining the links between received network support and marital quality among mothers of children with ASD: A longitudinal mediation analysis. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 50, 960–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, E.; Miniscalco, C.; Kadesjö, B.; Laakso, K. Negotiating knowledge: Parents’ experience of the neuropsychiatric diagnostic process for children with autism. Int. J. Lang. Comm. Disord. 2016, 51, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moh, T.A.; Magiati, I. Factors associated with parental stress and satisfaction during the process of diagnosis of children with autism spectrum disorders. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2012, 6, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidman-Zait, A.; Mirenda, P.; Duku, E.; Vaillancourt, T.; Smith, I.M.; Szatmari, P.; Bryson, S.; Fombonne, E.; Volden, J.; Waddell, C.; et al. Impact of personal and social resources on parenting stress in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2016, 21, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, R.N.M.; Torquato, I.M.B.; Collet, N.; Reichert, A.P.D.S.; Souza, V.L.D.; Saraiva, A.M. Infantile autism: Impact of diagnosis and repercussions in family relationships. Rev. Gaúcha Enferm. 2016, 37, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Comprehensive and Coordinated Efforts for the Management of Autism Spectrum Disorders. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB133/B133_4-en.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2019).

- Department of Universal Healthcare and Public Health of the Valencian Regional Government. Process of Comprehensive Care for People with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), 1st ed.; Valencian Regional Government, Department of Universal Healthcare and Public Health: Valencia, Spain, 2017.

- Orellana, C.E. Survey on the Diagnostic Quality in Autism. Available online: https://autismodiario.com/2017/12/05/encuesta-sobre-calidad-diagnostica-en-autismo/ (accessed on 12 October 2019).

- Alarco, J.J.; Álvarez-Andrade, E.V. Google Docs: An alternative online survey. Educ. Méd. 2012, 15, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Flower, P.; Larkin, M. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research; SAGE: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, G.L.; Gürtler, L. AQUAD 7. Manual: The Analysis of Qualitative Data; Ingeborg Huber: Tübingen, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| Items | 1(%) | 2(%) | 3(%) | 4(%) | 5(%) | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The physician informed me of the diagnosis in a cold and unempathetic way. | 29.4 | 14.7 | 23.5 | 17.6 | 14.7 | 2.74 | 1.442 |

| 2. The physician informed me of the diagnosis in a sensitive way and considered my emotions. | 23.5 | 8.8 | 26.5 | 17.6 | 23.5 | 3.09 | 1.485 |

| 3. I was hastily informed of the diagnosis and had little time to ask questions. | 38.2 | 11.8 | 23.5 | 11.8 | 14.7 | 2.53 | 1.482 |

| 4. The physician gave me time to ask any questions that I had. | 8.8 | 17.6 | 17.6 | 20.6 | 35.3 | 3.56 | 1.375 |

| 5. After communicating the diagnosis, the meeting ended without any further guidance. | 41.2 | 20.6 | 20.6 | 5.9 | 11.8 | 2.26 | 1.377 |

| 6. After communicating the diagnosis, positive and hopeful messages were provided. | 20.6 | 8.8 | 32.4 | 14.7 | 23.5 | 3.12 | 1.431 |

| 7. After communicating the diagnosis, I was given advice on possible support measures and resources. | 14.7 | 8.8 | 23.5 | 29.4 | 23.5 | 3.38 | 1.349 |

| Items | 1(%) | 2(%) | 3(%) | 4(%) | 5(%) | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Reinforce the training of the physicians involved. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.9 | 11.8 | 82.4 | 4.76 | 0.554 |

| 2. Shorten the average time elapsed between the identification of symptoms and the final diagnosis. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.8 | 11.8 | 79.4 | 4.71 | 0.629 |

| 3. Increase emotional support throughout the process. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.9 | 11.8 | 82.4 | 4.76 | 0.554 |

| 4. Improve the actual communication of the diagnosis. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 17.6 | 79.4 | 4.76 | 0.496 |

| 5. Provide more information and guidance after the diagnosis. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.9 | 94.1 | 4.94 | 0.239 |

| 6. Strengthen emotional support after the diagnosis. | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.9 | 8.8 | 85.3 | 4.79 | 0.538 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roig-Vila, R.; Urrea-Solano, M.; Gavilán-Martín, D. The Quality of Autism Spectrum Disorder Diagnosis: Families’ Views. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10090256

Roig-Vila R, Urrea-Solano M, Gavilán-Martín D. The Quality of Autism Spectrum Disorder Diagnosis: Families’ Views. Education Sciences. 2020; 10(9):256. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10090256

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoig-Vila, Rosabel, Mayra Urrea-Solano, and Diego Gavilán-Martín. 2020. "The Quality of Autism Spectrum Disorder Diagnosis: Families’ Views" Education Sciences 10, no. 9: 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10090256

APA StyleRoig-Vila, R., Urrea-Solano, M., & Gavilán-Martín, D. (2020). The Quality of Autism Spectrum Disorder Diagnosis: Families’ Views. Education Sciences, 10(9), 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10090256