1. Introduction

What factors help students with mental illness or disabilities to study successfully? As early as in the 1970s, this question was already investigated in detail with a focus on academic and social integration [

1,

2]. The American studies of Tinto as well as Morrison and Silverman showed that for students with and without health problems, academic integration is important for academic success. In other American quantitative studies in particular [

3], students were divided into groups according to certain criteria and it was examined whether these groups differ in terms of their academic success. This refers to 1. the type of health impairment, 2. its immediate visibility for third parties, and 3. the status of the health impairment. These three criteria have an impact on the students’ success. The decisive factor is, on the one hand, the visibility of the impairment and, on the other hand, whether an impairment has been officially confirmed or not. According to Pingry O’Neill, Markward, and French, the form of impairment is also related to academic success. Their study involved 1289 students at three American universities, and the results suggest that students with physical impairments are more successful in their academic studies than those with cognitive impairments [

3]. Another study examined how the form of impairment affects the students’ ability to remain in higher education in the medium and long term [

4,

5]. In this panel study, 23,090 students at 1360 universities were interviewed, including 890 students with impairments. According to this study, a key criterion for academic success is whether the students make a successful transition from the first to the second year of study and then stay at the university beyond that. A central and highly interesting result is that students with learning impairments and physical disabilities are significantly more successful in their studies than students suffering from mental illness (especially depression) [

4,

5]. According to Fisseler, the results indicate that universities are less well prepared for certain impairments than for others [

6]. This does not allow any conclusions to be drawn as to whether students with certain impairments are more or less successful. The visibility of disabilities and mental illness for third parties is, in most cases, significantly limited and can unintentionally lead to a disadvantage or the perception of disadvantage in the students’ academic endeavors [

6]. A longitudinal study by Wessel et al. examined 17,317 students, including 173 students with disabilities and mental disorders, and showed that academic success does not depend on health restrictions [

7]. These findings are supplemented by the results of a study by Adams and Proctor with 230 students, including 115 students with disabilities [

8]. The researchers were able to show that students with health impairments are more likely to feel that they do not belong at a university. As a consequence, disabled students are more likely to think about quitting. There were also differences within the group of students with disabilities. Students with rapidly recognizable impairments were more successful in adjusting to their studies. The authors see one reason for this in the fact that these students have to explain themselves to third parties less often than students with imperceptible impairments [

8]. According to Fisseler, these results suggest that visibility is more likely to affect the attitudes and behavior of others towards students with disabilities. These attitudes can have an impact on how the impaired students are dealt with, and also on the provision of services for these students, which then has an effect on their academic success [

6]. In our own study we will examine this point in more detail.

Among the many factors that can affect the academic success of students with disabilities or mental illness, institutional factors are becoming increasingly important—most notably, the provision of services for students with disabilities (such as implementation services, counselling services, special work spaces), compensation for disadvantages, and appropriate precautions (such as extended processing times, alternative examination offers, accessible materials). The attitudes of staff and teachers towards students with health impairments constitute another institutional factor (see below). Various studies show that students with disabilities or mental illness have the same academic success as others when they have access to institutional support systems, indicating that the institutional level is indeed of great importance [

7,

9,

10,

11]. Nevertheless, this form of support is not established at all universities. For example, a study from Norway showed that students with disabilities or mental disorders still have problems in their studies [

12]. In view of the different results, it would be interesting to investigate how students with disabilities or mental disorders perceive the situation at German universities.

On the basis of various studies, it can be cautiously deduced that the attitudes of employees and teachers at universities also have an influence on academic success. For example, the qualitative study by Shevlin, Kenny, and Mcneela in Ireland reported various problems: problems with taking the transcriber’s assistant to courses, problems with teachers who do not provide materials for implementation, and a general ignorance of the needs of students with health impairments [

13]. A similar study was conducted by Fuller, Bradley, and Healey in the UK [

14] (173 questionnaires and 20 narrative interviews). One of the obstacles mentioned is the teachers’ attitudes towards the topic of disability, which results, among other things, in the refusal to compensate for disadvantages. Similarly, the students interviewed also reported positive experiences in connection with teachers who have contributed to their academic success [

14]. Duquette evaluated the attitude of teachers as a factor influencing academic integration and thus indirectly also the students’ remaining in the university. However, she does not support this argument empirically [

15].

It seems obvious that including didactic concepts for higher education may positively influence the academic success of students with and without impairments. However, according to Fisseler, relatively little research has been conducted into the effects of didactic factors on the academic success of students with disabilities, even though the universal design concept is very widespread in the American region [

6]. It is true that there are some studies that identify teaching as a critical factor that can be both a barrier and a positive experience for students with health impairments [

12,

16,

17,

18]. However, what is lacking in the field of higher education research is a systematic investigation of influencing factors or an evaluation of different teaching concepts. One of the few empirical studies in this field was conducted by Schelly, Davies, and Spooner (2011) [

19]. The researchers examined how effective it is to train teachers on Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and whether students are aware of the implementation of the principles of UDL. A total of 1223 students and 9 teachers took part in the study. The authors found that students noticed a significant difference in some aspects of teaching and perceived positive changes in the design of teaching. Schelly, Davies, and Spooner (2011) therefore saw positive effects of UDL training on the learning experiences of all students [

19].

Looking at international research on the situation of students with disabilities or mental disorders, it becomes clear that the students’ situation is largely dependent on local conditions. On this basis, it is worthwhile to take a closer look at the experiences of students with disabilities or mental disorders at German universities.

In the context of the implementation of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) at German universities, the recommendations issued by the German Rectors’ Conference (Hochschulrektorenkonferenz, HRK) and the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs (Kultusministerkonferenz, KMK) in 2015 call on universities not only to prepare their students for the situation of inclusion in German schools and society, but also to lead by example [

20]. The researchers Dannenbeck and Dorrance describe inclusion in the university context as follows: “Rather, inclusion would only prove itself in the effort to effectively counteract barriers and discrimination processes that can affect students in all their different life situations. [...] From the perspective of inclusion theory, this would result in the need to focus on discrimination and disadvantage mechanisms instead of being content with just a slightly higher level of integration of disabled people” (own translation) [

21,

22].

In Germany this perspective has gained in importance over the last years. Teaching inclusion inclusively has become one of the main topics of several teacher education programs at many different German universities [

23,

24]. In order to translate this understanding of inclusive education into practice, TU Dortmund University has launched the DoProfiL research project (Dortmunder Profil für inklusionsorientierte Lehrer/-innenbildung—Dortmund profile for inclusion-oriented teacher education), an interdisciplinary project funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. In this research project, inclusion at schools and universities is investigated and developed in different sub-projects [

25]. With the present article, I would like to contribute to my own sub-project on reflective inclusion and point out one important perspective of inclusive teacher education [

26,

27]. This perspective focuses on university teachers and their efforts to make seminars and lectures as inclusive as possible. This approach indicates that lecturers at TU Dortmund University and other universities recognize the diversity of their students. Therefore, they want to consider the different individual learning conditions of all students without overlooking the support needs of disabled students. This is based on a certain understanding of disability. At TU Dortmund University and other higher education institutions, disability is not understood as a physical or mental disorder affecting a person. Rather, disability is seen as the result of an interaction between a person and his or her environment. This means one has to ask oneself over and over again whether someone is disabled or whether this person’s disability results from other people’s actions and/or other circumstances [

10,

21,

28].

I am a researcher and lecturer, and I have a disability. Therefore, it is a matter of special concern for me to not only preach inclusion, but to show my students what inclusive teaching can look like by making it part of my courses [

28,

29]. It is important to me that all students can participate in learning processes without problems. Together with other colleagues at TU Dortmund University, I have been organizing my courses in an inclusive way for three years [

28]. In doing so, we have been using the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) Guidelines [

30,

31]. The Universal Design for Learning developed in the U.S. is a promising method to constructively manage diversity in inclusive learning processes. It can help to identify learning barriers in advance and manage different learning strategies and levels [

30,

31]. The three basic principles of Universal Design for Learning help to focus on the different learning requirements of students:

The first principle can be realized by ensuring that students have access to information in different formats. Based on various empirical studies, it is assumed that learning is effective when learners have different approaches to learning materials [

8,

30,

31]. Students who are visually oriented can use printed texts. Students who have difficulties processing visual information can listen to voice recordings of texts. This form of representing learning content does not only help students who are blind or visually impaired, however—students who are affected by dyslexia can also benefit from this form of representation. Over the years, we have seen that students with children also make use of auditory formats because they can listen to recordings on their way to university. In some of my interviews in the context of using Universal Design for Learning at universities students reported that learning in a less visual form was good for them.

According to our experiences it is important that students have a choice. The second UDL principle (action and expression) can be implemented by actively encouraging students to learn. This means, for example, letting them choose how they wish to present their results from a group work session. For instance, students who are afraid of speaking in front of large groups may organize a digital writing conference to discuss their results with others. Others, for example, who do not want to give a traditional oral presentation may make a film, organize a panel discussion, or record a podcast. The possibility of new forms of expression enables students to develop individually. The third central UDL principle is engagement. This means that students should learn in a way that is guided by their interests as much as possible. In teacher training, this can be implemented by including practice-oriented formats such as visits to schools to enhance motivation. If student teachers can develop a didactic concept of their choice in the framework of a university seminar and then try it out in real life, their motivation to work is definitely stronger than in a purely theoretically-oriented learning setting. Furthermore, it seems to make sense to let students have a say and make their own suggestions.

Even though there are efforts to make teaching at universities inclusive, students with disabilities at various German universities have pointed out to me that they are facing difficulties in their studies. These problems are related to their disability and are not only of a structural nature. Rather, they are indications that learning processes themselves are designed in such a way that they put people with disabilities at a disadvantage [

32].

According to the results of the study “beeinträchtigt studieren 2”, which was conducted with 20,987 participants in 2016/17, 11 percent of a total of 2.8 million students in Germany are affected by a disability [

33]. Of these persons, 96 percent state that their disability is not immediately visible to others. Ninety percent of the participants pointed out that they have many difficulties in their studies because of their disability. Forty-four percent of the statements referred to the social interaction at the university. Thirty percent of the students with disabilities in Germany make use of disadvantage compensation in their studies. The study also found that 30 percent of the students ask their family members to help in difficult situations [

33]. These results are astonishing. In 2009 the UN CRPD created a binding legal basis for ensuring the rights of people with disabilities [

34]. This means, for example, that people with disabilities must neither be discriminated against nor stigmatized on the basis of their disability. Furthermore, it means that people with disabilities have the right to participate fully in society, and thus also in education. The study “beeinträchtigt studieren” shows that we still have a long way to go to an inclusive university. At the same time, the study does not provide detailed insights into the individual situations of disabled students in the context of learning processes. My own case study should help us to understand more precisely what problems and difficulties disabled students face. The learning process itself is examined and reflected upon more closely. Based on the results, new further implications for inclusive university didactics are formulated.

In the study presented below, I have followed up on the question of how disabled students experience inclusive higher education at German universities in general and what individual experiences they have made in this context exactly. Within the framework of the study I have deliberately taken a critical perspective. What kind of (learning) barriers can be identified? Are there problems concerning the interaction with teachers or with other students? What do disabled students suggest in order to improve their situation? These were the questions which led me to conduct the study, aiming to get closer insights into the experiences of disabled students at German universities. In order to be able to answer the above-named questions in a differentiated manner, a mixed-methods approach is considered helpful [

35]. Within the framework of the quantitative research approach, the following research hypotheses, which were developed on the basis of the study “beeinträchtigt studieren”, are to be tested:

Students with disabilities report to have encountered problems in their studies that are related to their disability;

Students with disabilities report to have encountered problems with spatial barriers;

Students with disabilities report to have encountered no problems with the learning materials used in their studies;

Students with disabilities report to have encountered no problems with their lecturers;

Students with disabilities report to have encountered no problems with other students;

Students with disabilities report to have encountered problems regarding the effects of coronavirus on their studies.

The quantitative data will provide insights into overarching trends in student perception about inclusive education at universities in Germany. Furthermore, it seems promising to interview students qualitatively in order to gain more individual and differentiated insights into their experiences [

26].

2. Materials and Methods

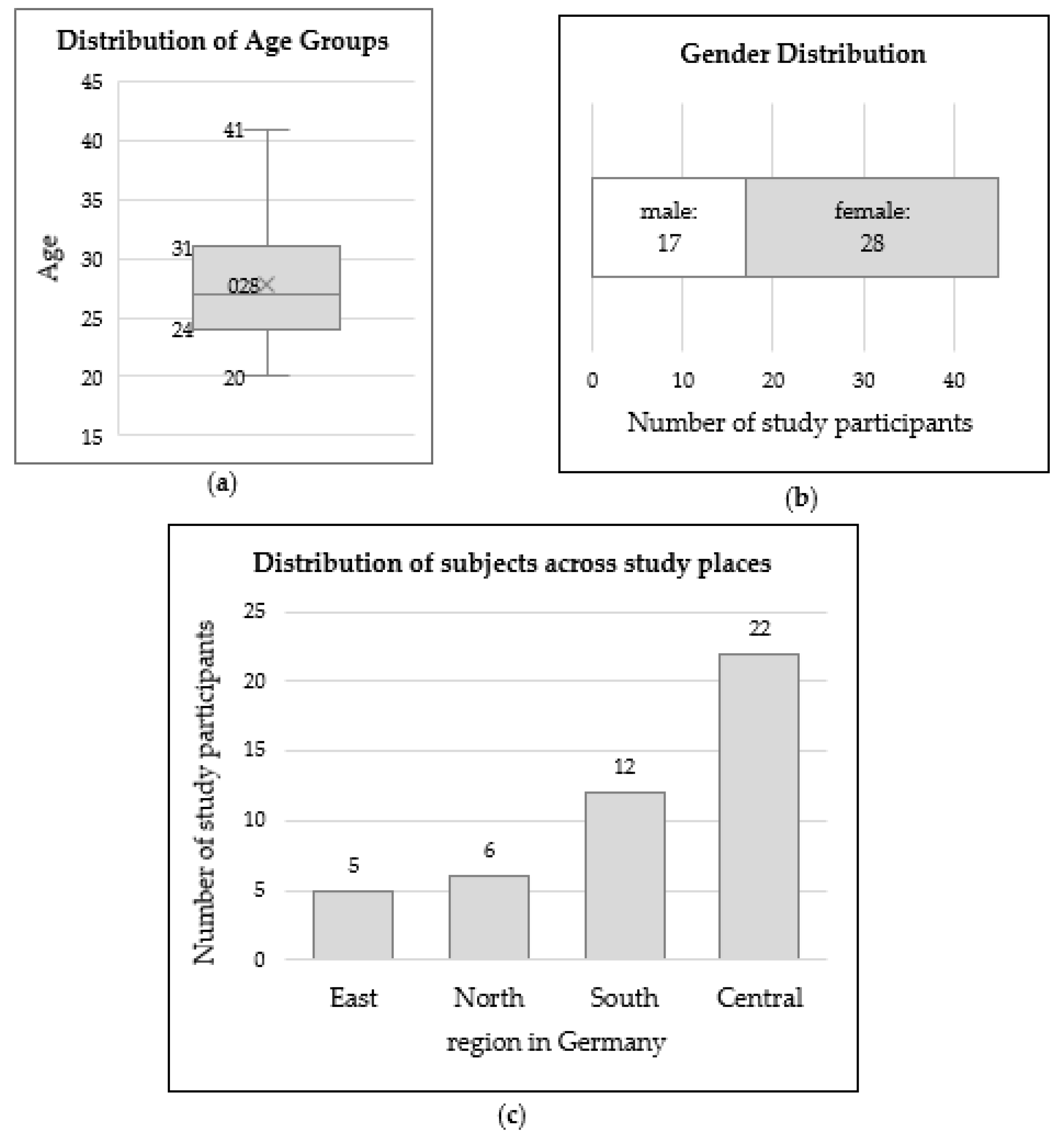

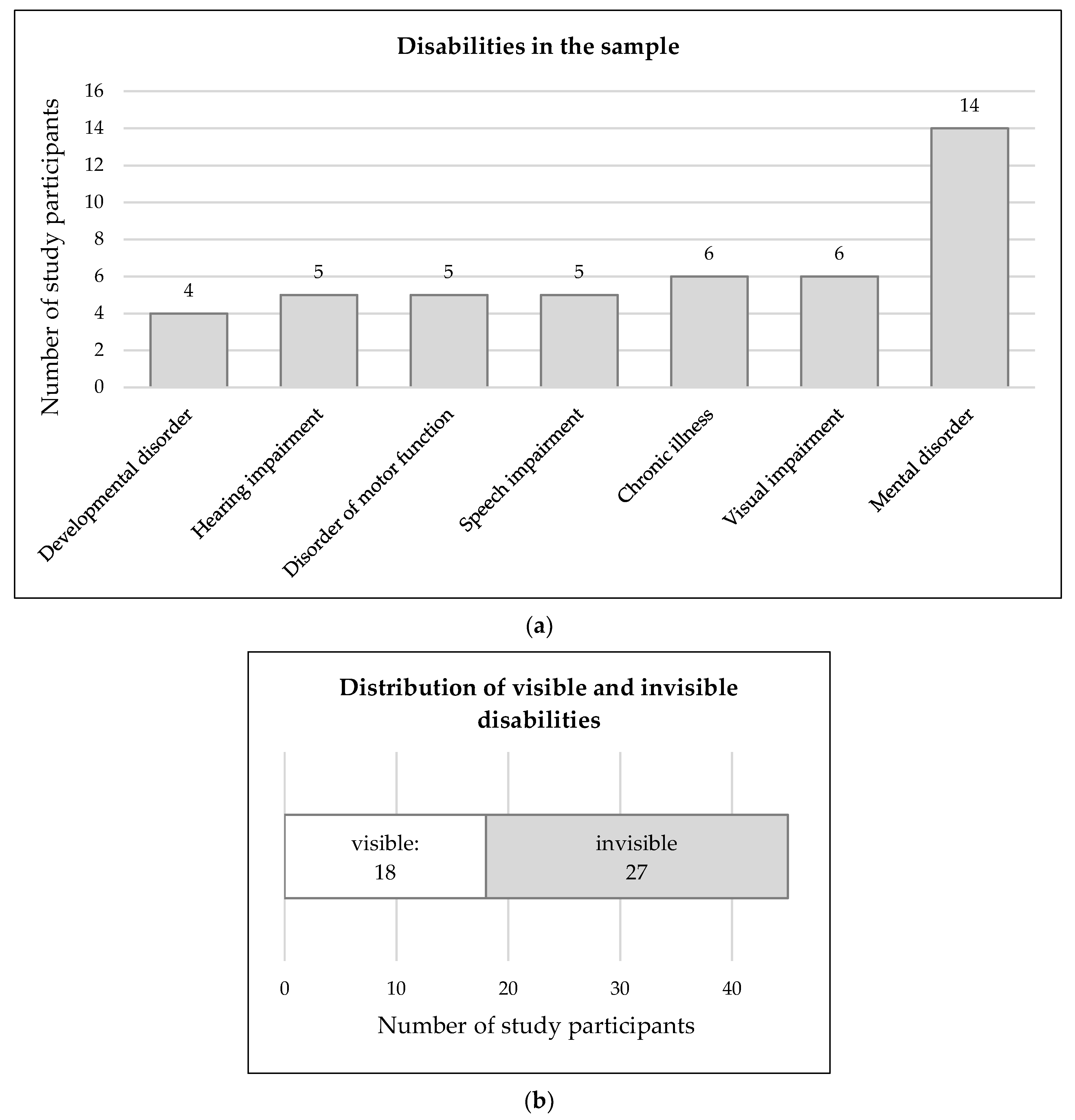

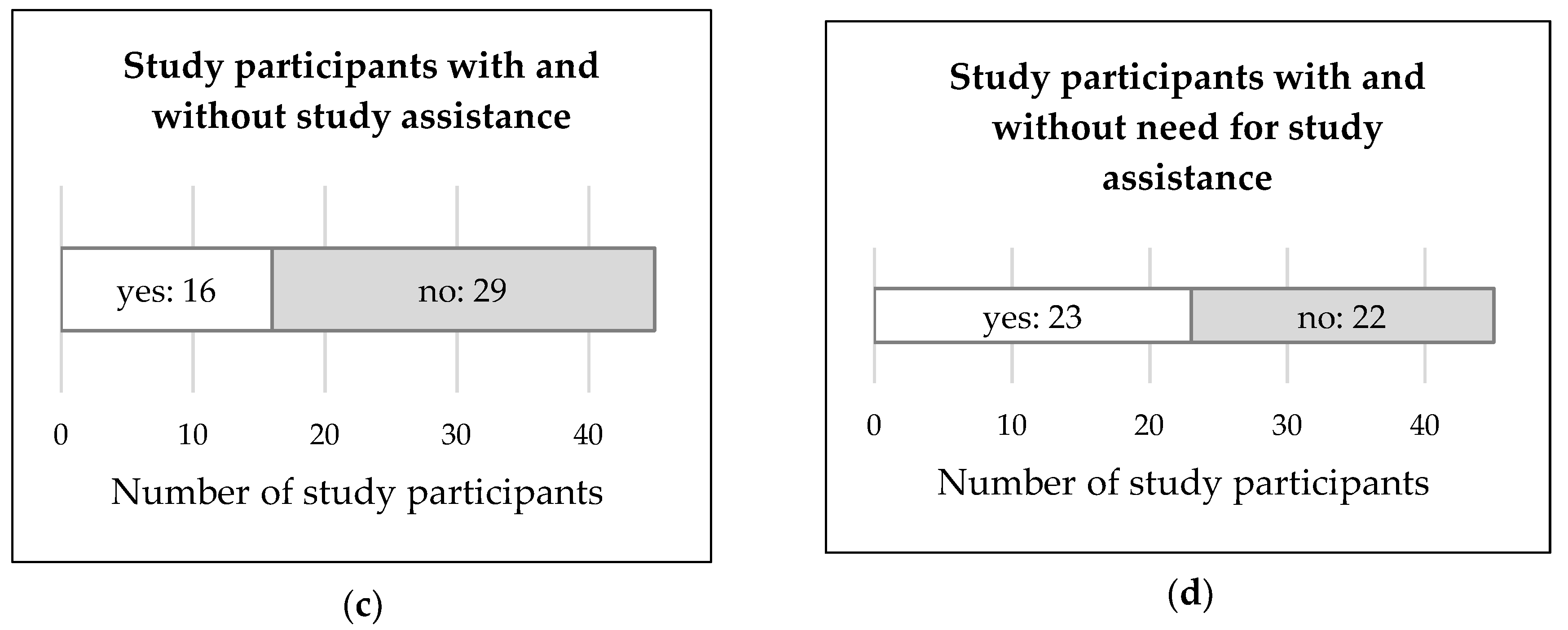

As mentioned before, I chose a combination of quantitative and qualitative survey methods for this study, with the intention of not only providing general insights into the situation of disabled students at German universities but also of gaining some more individual insights into the experiences of disabled students. With the mixed-methods-approach, I aimed to achieve a better understanding of the learning situation of disabled students at German universities [

35,

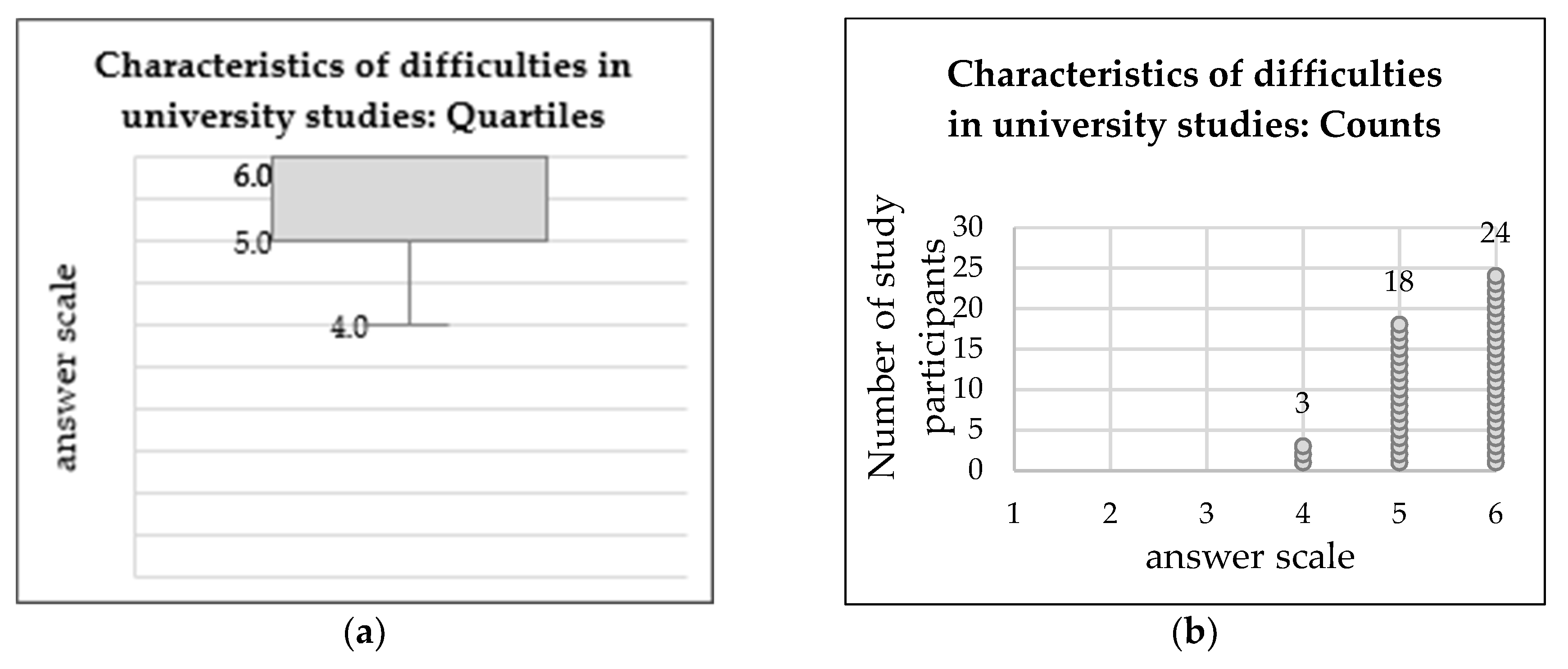

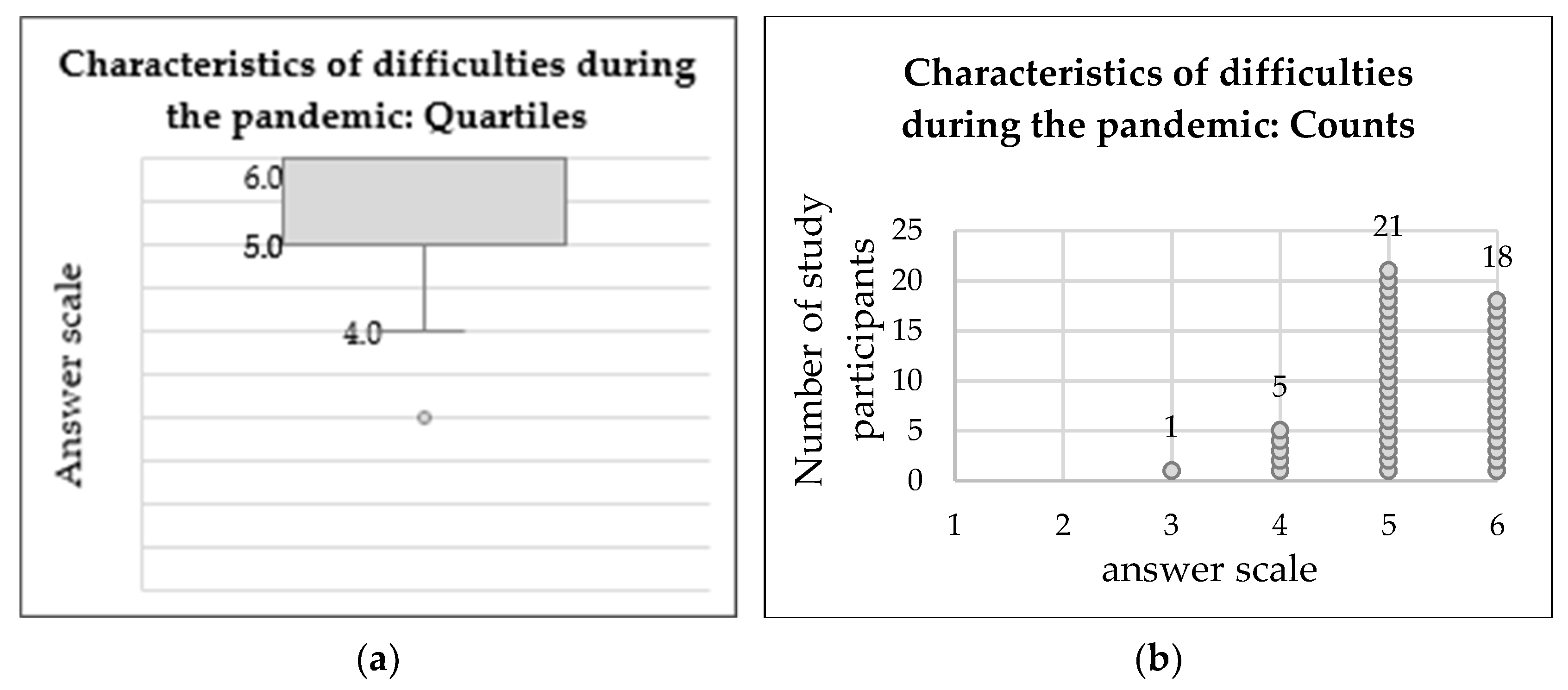

36]. A total of 45 students with different disabilities from 35 universities took part in the survey. They were interviewed quantitatively as well as qualitatively. Both data sets were collected over a period of 12 weeks (March–June 2020). In the quantitative part of the survey, the disabled students had the opportunity to describe their experiences with regard to six main items: problems encountered during their studies because of disability (1), problems concerning spatial conditions at universities (2), problems concerning the learning materials used in lectures at universities (3), problems concerning the attitudes of lectures at the universities (4), problems concerning the interaction with other students at their universities (5), and problems concerning the special situation of the COVID-19 pandemic (6). On a Likert scale of 1–6, the surveyed students were able to indicate how pronounced these problems are for them [

37]. A value of “1” means that the respondent strongly disagreed with the respective statement and a value of “6” means that the respondent strongly agreed with the respective statement. In the qualitative part of the study the students were interviewed in narrative interviews [

36]. The students’ description of their current study situation and their understanding of their own disabilities served as the basis for the interviews, which lasted between 40 and 60 min. The leading question used for the interviews was: as a person with a disability or mental illness, would you please tell me about your academic studies and your experiences at university? In this way 12 students were interviewed.

In a first step, the data of this survey were analyzed using uni- and multivariate statistical methods (evaluation of frequencies and location parameters, checking for significant independence of prominent subsets) [

35]. The characteristics “age”, “gender”, “study region”, and “type of disability” were treated as independent variables and the students’ statements on the items “problems regarding their studies”, “problems with spatial barriers”, “problems with learning materials”, “problems with lecturers”, “problems with other students”, and “problems regarding the effects of coronavirus” were treated as dependent variables. The analysis procedure was implemented using the “R” programming language [

38]. Chi-square goodness-of-fit tests were used in the sample analysis to ensure the balance of the sample [

39]. This was possible due to the sample size of

n > 20. In contrast, Fisher’s exact test was used to identify possible dependencies between the values of dependent and independent variables, because single features are likely to be observed less than five times [

40,

41].

As part of the quantitative analysis, the above-mentioned variables based on global judgements of the study participants were evaluated in relation to the hypotheses formulated above. The results of this investigation determined the selection of the sample for the qualitative sequence, in which fine-grained dependent variables were to be explored [

35,

36]. The selection criteria for data sets of the qualitative sample were (1) prototypical examples with an intermediate-level representation of the dependent variables, (2) prototypical representatives of distinct subgroups with significantly different assumptions about the study situation, and (3) outliers. The qualitative dataset was analyzed using Mayring’s qualitative content analysis method [

42] with the objective of structuring the students’ comprehensive reports. As regards data evaluation, the deductive approach was chosen. This means that in order to find answers to the research question, the following seven categories were defined: detailed information about problems during university studies because of disability (1), individual problems concerning spatial conditions at universities (2), closer insights into problems concerning the learning materials used in lectures at universities (3), individual reports about problems concerning the attitudes of lectures at universities (4), insights into problems concerning the interaction with other students at universities (5), individual perspectives on problems concerning the special situation of the COVID-19 pandemic (6), and the suggestions put forward by disabled students to solve the problems (7).

4. Discussion

Looking at the results of the study, the following picture emerges with regard to the research hypotheses and research questions (cf. 1.).

1. It has been confirmed in many ways that students with disabilities report to have encountered problems in their studies that are associated with additional expenses due to their disability. The interviews provided vivid insights into the diversity of the problems. At this point it can be said that my own study with regard to German universities confirms the results of international research in this field [

6,

12,

13]. In the course of the further implementation of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities at German universities, these diverse and individual problems should be listened to by those responsible. The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, in particular Article 5, mentions that people with disabilities should be treated equally and not be discriminated. According to Article 5 paragraph 3, the contracting states are committed to taking all necessary steps to promote equality and eliminate discrimination at universities. The individual experiences of students show that there is still potential for improvement at German universities in order to achieve this important goal. The students’ individual statements can be an indication that the responsible persons at German universities should take a closer look at equal rights and discrimination in the context of disability and mental illness. In addition, the contracting states have undertaken to provide access to higher education for people with disabilities (Article 24, paragraph 5). The individual reports of the interviewed students showed that it is not enough to guarantee access to a university. Rather, in view of the international findings regarding the academic success of disabled students, it is more important that people with disabilities and mental illness are supported in such a way that they can successfully complete their studies. If there are problems in achieving this goal, these problems not only complicate the students’ everyday lives, but also jeopardize equal and continuous access to education and the retention of students with disabilities or mental illness.

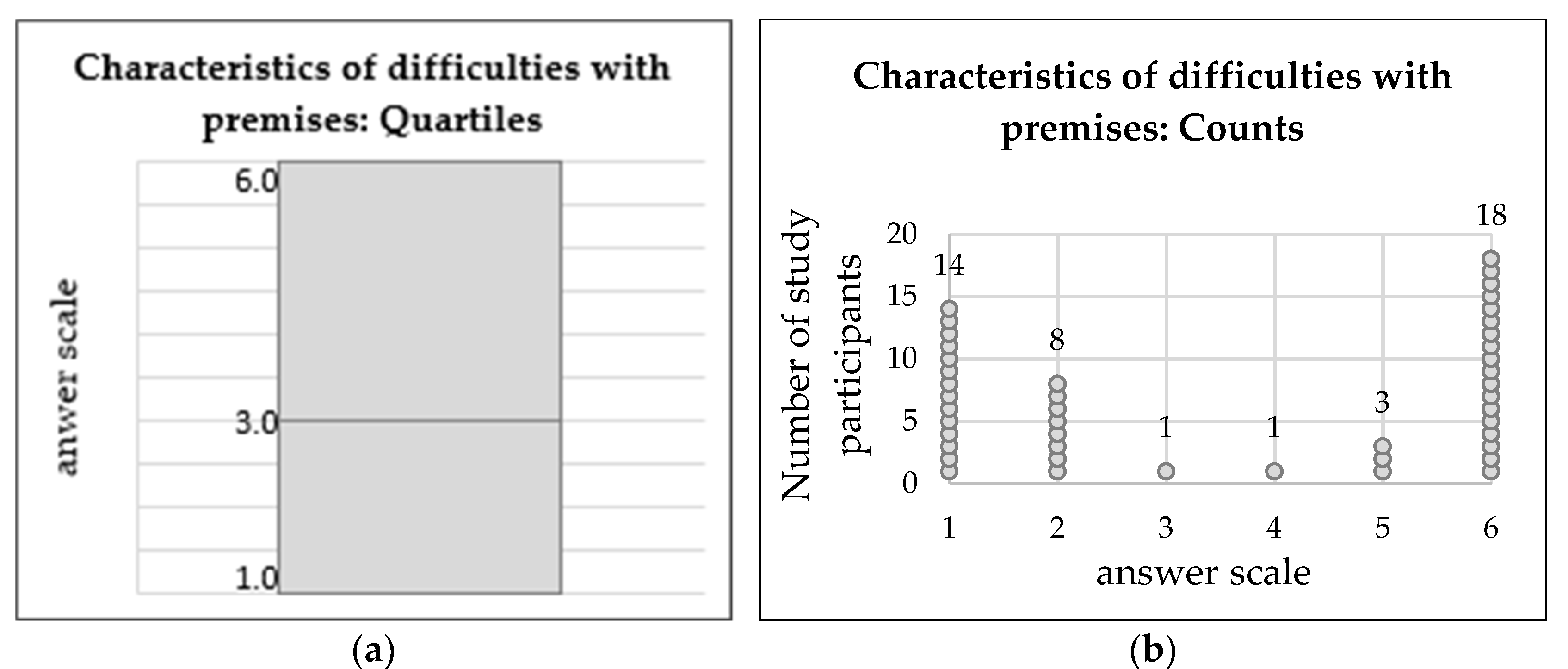

2. Students with disabilities pointed out problems regarding spatial barriers. The present study has shown that not only students with physical disabilities have problems with the design of university premises, but that there are also considerable and comprehensible barriers for students with mental disabilities, which, according to the students’ statements, have not yet arrived in people’s consciousness. The students’ experiences indicate that there is still a need for action with regard to accessibility at German universities. It is vital to raise awareness of the individual barriers faced by disabled students when planning and implementing university lectures. Particularly impressive are the comments from students with mental disabilities. In addition to structural changes, a dialogue between the parties involved is also important and useful in order to reveal barriers and find common solutions. Even a poorly equipped room can result in learning being hindered. Changes in this respect would certainly be of great benefit to all students.

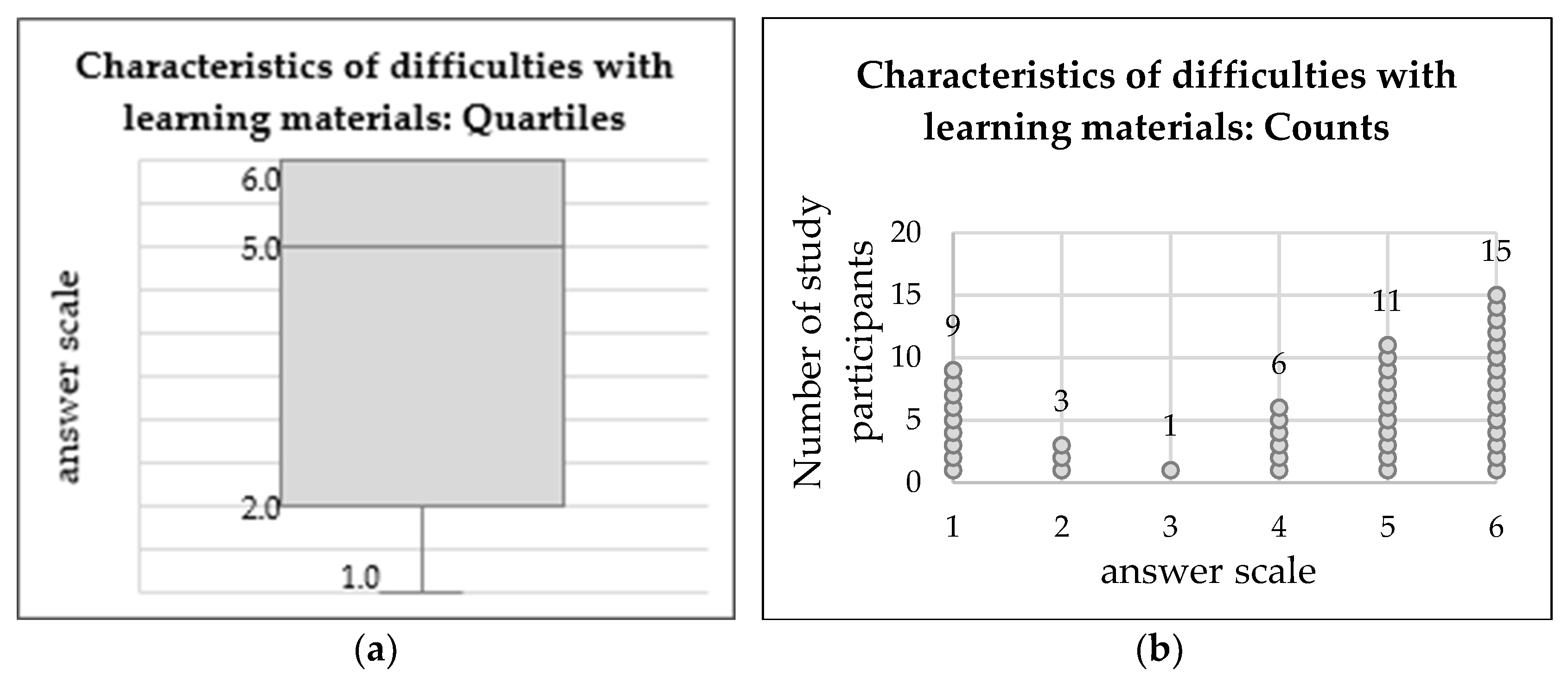

3. The results in connection with the learning materials are astonishing. It is generally assumed that digitization leads to a greater accessibility of learning materials. According to the information provided by students with disabilities, this does not seem to be entirely true. Also, it is interesting to note that the timing of the provision of learning materials is very important, especially for students with mental disorders. Accessibility of materials therefore means more than producing well-formatted document. For the future, it is recommended that lecturers are comprehensively informed about the accessibility of learning materials. It is imperative that lecturers consider which barriers students might encounter when creating learning materials. A timely provision of materials in different formats seems to make sense here, in accordance with the Universal Design for Learning. However, it is also important to determine the quality of the learning materials in feedback formats with all students and to change them if desired. If this is not possible, for example, due to the high workload of lecturers, access to education for students with disabilities is restricted—and this is a problem that should be solved on the structural level.

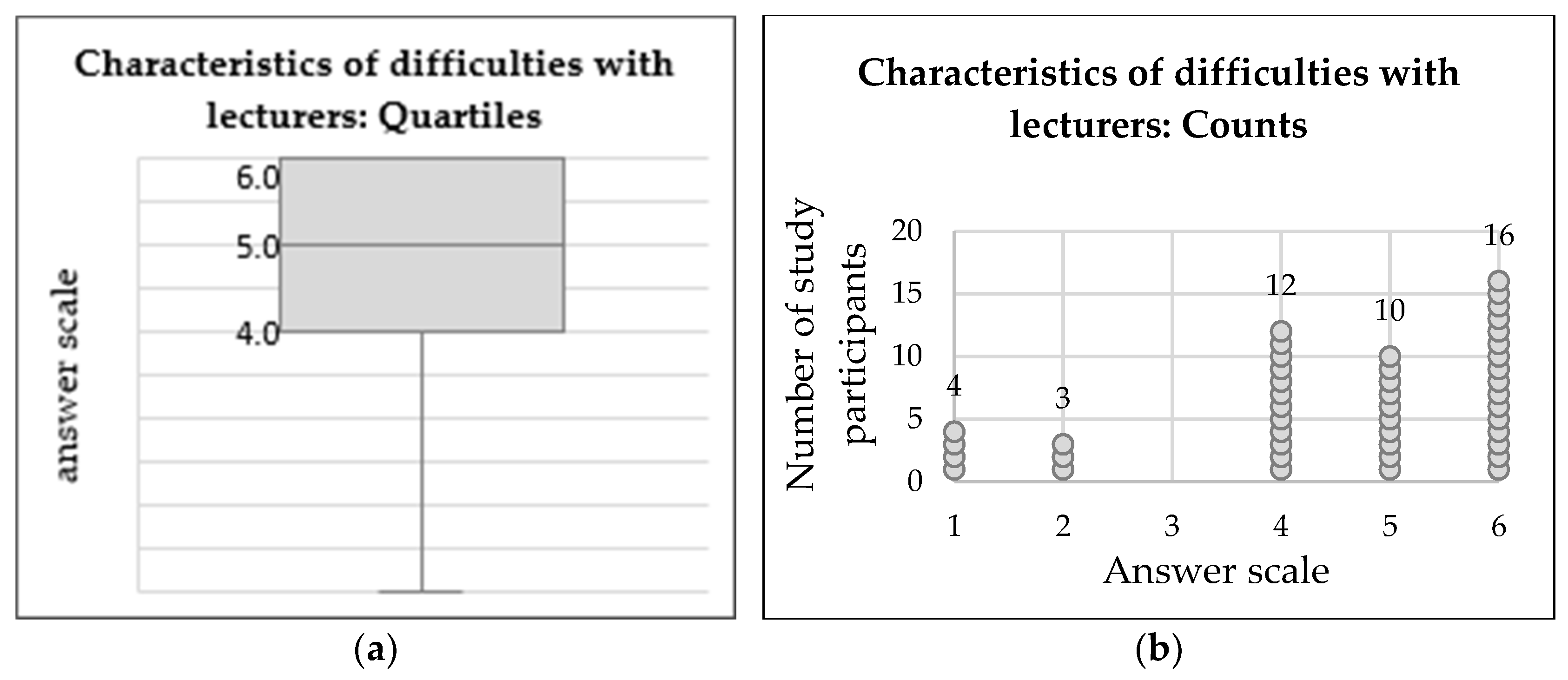

4. The results are particularly reflective of the experiences disabled students have had with their lecturers. A large proportion of the students stated that they have had problems with lecturers. The case studies showed that these problems are very diverse and sometimes involve additional work for the lecturer. What is also frightening is that university teachers make statements such as those described by the students which, in my opinion, are quite discriminating. If a disabled student cannot enter a lecture hall with their wheelchair, ways and means have to be found to remedy the situation. The fact that disabled students are not taken seriously as experts on their disabilities is particularly alarming when such an attitude is adopted by lecturers who should be familiar with the subject of disability. These individual, interpersonal problems between disabled students and lecturers indicate that a lot of information and exchange is still needed in these concrete cases. Certainly, these examples are not generally representative of the situation of disabled students at German universities. Nevertheless, it is irritating that in a country like Germany, which is committed to human rights and the rights of disabled people, some people at universities have to experience extreme forms of prejudice and discrimination with regard to disability and skin color. Even if such experiences occur occasionally, they show, especially with regard to Article 5 and Article 24 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, universities should devote more attention to discrimination processes and develop solutions for more equality because there is a gap between policy and practice.

Based on the interviews with study participants, the following needs for action can be identified for the implementation of the UN CRPD at German universities in order to close the existing gap between diversity policy and higher education practice: (a) lecturers should be made aware of the situation of students with disabilities and trained as a matter of obligation; (b) there is a need for more precise knowledge of why lecturers deny students certain rights. In particular, it remains to be clarified whether it is a matter of personal attitude or increased workload; (c) disabled students in particular should have the right to equal participation in German higher education without being discriminated against or having to justify their situation.

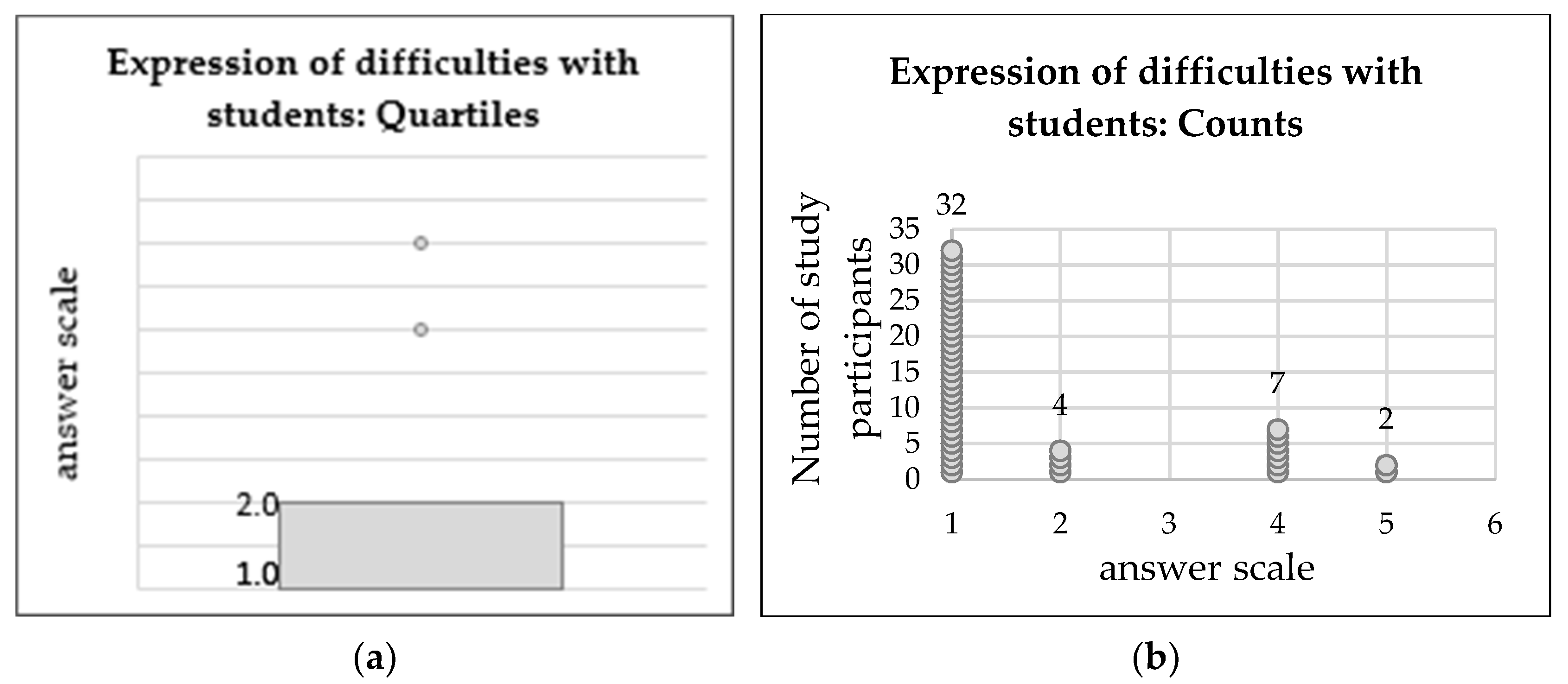

5. Fortunately, the interaction between students with and without disabilities is predominantly positive. However, the example of Sven (cf. 3.2.3.) shows that barriers in people’s minds have still not been broken down. Certainly, values such as empathy and understanding are difficult to implement in a performance-oriented environment like the university. The interviews generally gave the impression that students at large universities think more of themselves and find it difficult to understand the situation of disadvantaged fellow students. For instance, some study participants reported that fellow students compare their disability with everyday challenges such as stress in their studies or compatibility of leisure time and studies. This shows that in some cases there is a lack of awareness that a disability is not comparable. From the interviews, it became clear that many students with disabilities spend their “free time” visiting a doctor or undergoing therapy or dealing with bureaucracy and administration. This is not a time for rest. It turns out that it is important to make others aware of the additional costs that arise from a disability.

Nevertheless, the overall results allow us to draw the cautious conclusion that students with and without disabilities get along well with each other when taking the individual vulnerability of the other person seriously [

33]. This form of encounter should be positively supported and extended to other areas of university life and teaching in the future.

6. Looking at the data concerning the information provided by disabled students on their experiences in connection with COVID-19, one can observe that even in the context of enormous challenges, students with disabilities are on the losing side. The empirical data of the study essentially show that the pandemic is making the strong stronger and the weak weaker. This lack of solidarity and understanding is particularly evident in the lecturer’s statement equating a person’s disability with the situation of raising a child. This line of argumentation is not comprehensible, because the comparison of two fundamentally different individual situations is absurd. From a scientific point of view, it can be expected that even in a pandemic situation people will act in such a way that people with disabilities will not experience discrimination. According to the preamble of the UN Disability Convention, disability is a construct that arises from the interaction between people with disabilities and the barriers of attitudes and environment that prevent them from participating in society fully, effectively, and on an equal footing. In the context of higher education, this means that special consideration should be given to the situation of people with disabilities, particularly during this pandemic. Barriers caused by the pandemic should be dismantled if possible in order to alleviate further barriers in everyday life. Drawing comparisons between individual life situations is not helpful [

32,

43]. It should not become the norm for a person unaffected by disability to judge the situation of a person with a disability. Students with disabilities have almost certainly not chosen their disability and are permanently restricted. If they point out barriers, it should be possible to meet them respectfully and take them seriously as experts of their situation [

20]. Comparisons with other groups of people or situations are not appropriate.

This case study has shown that for disabled people access to education at German universities is sometimes restricted. A special focus was placed on the accessibility of learning processes. It turns out that these learning processes are hampered by individual prerequisites, but also by external influences.

By applying Universal Design for Learning in their own courses, I believe that lecturers could identify many learning barriers in advance [

20,

21]. A conscious examination of possible problems in the processing of the learning material helps to focus on the individual learning processes of students and to motivate and support each individual person. However, the inclusive design of courses also requires structural support. In the interviews, the disabled students at large universities reported of lecturers who are overburdened at various levels. They are under great pressure due to the large number of course participants, with courses being subordinate to actual research work. Within the framework of concrete studies on the working conditions of lecturers in inclusive learning settings, it should be clarified which stress factors prevent lecturers from making their courses inclusive. In view of the information provided by the students surveyed here, structural support is required. There is a need for qualification programs, expanded personnel and material resources, and an appreciation of the focus on inclusion.

However, in order to enable this constructive approach to diverse learning, a reflective and critical attitude is also necessary [

34,

44]. In accordance with the concept of reflective inclusion [

26,

27,

44], students in the context of teacher education are made aware of how diversity can be used constructively [

17,

34]. Such awareness should also be the subject of further training in the didactics of higher education. If one wants to learn from the statements of the surveyed students with disabilities, it is not enough to create barrier-free documents. It is much more important to be prepared to design courses in a participative and exemplary way. If the stigmatizing experiences reported in the study are to be considered, a stronger awareness is needed that the individual study situation of a person has a considerable influence on the learning situation and learning success. What is needed is an attitude of lecturers to allow students continued access to education, because it is their right.