Performance Appraisal in Universities—Assessing the Tension in Public Service Motivation (PSM)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

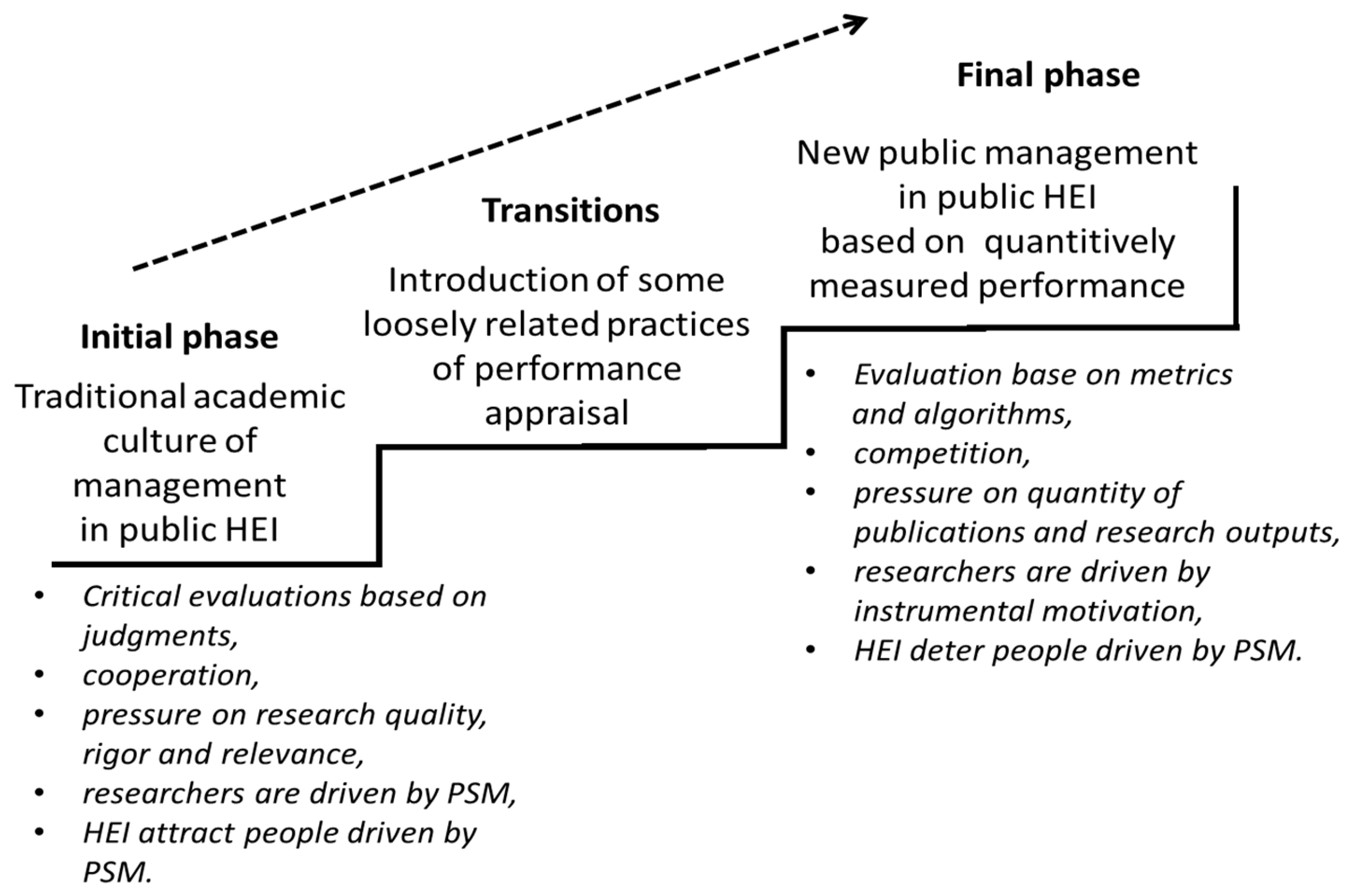

2.1. Adapting Performance Management Practices from the Business Sector to Public Institutions

2.2. Performance Appraisal in HEIs

2.3. The Effects of the PA System on HEIs

3. Methodology

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Jagiellonian University (JU) is the oldest Polish university, founded in 1364 and perceived as a national heritage. It is a comprehensive University educating and conducting research in over 30 scientific disciplines in 16 faculties. It is listed second in Poland in terms of scientific achievements and has ambitions of global development. JU has more than 41,000 students, and 3800 academic staff in 28 scientific disciplines. The JU cooperates with 240 partner universities in 52 countries. The JU is the member of following international associations: EUA, Unaeuropa, Coimbra Group, Aucso, Baltic University Programme, Eunis, The Guild, Europaeum, Sar. |

| Wrocław University of Economics (WUE) was founded in 1947 in Wroclaw as a one-faculty school. Presently, WUE is one of the top public economic schools of higher education in Poland and has 4 faculties. It has more than 17,000 students and 550 academic staff. WUE is the member of international institutions (European University Association, Global Division Santander Universidades, CFA Institute, European Institute for Advanced Studies in Management) and cooperates with 204 universities based in 27 European countries and in the USA and China. |

| The University of Malta (UM) lies at the middle of the Mediterranean and it was established in 1769. At UM, academic research is carried out that provides a vibrant higher education setting in the arts, sciences and the humanities. Courses are designed to produce highly qualified professionals in more than 120 academic disciplines. The total student population of the University is 12,000 and it employs around 3000 academic staff. Today, UM is composed of 14 faculties, 18 institutes, 13 centres and 3 schools. Besides the main campus, situated at Msida, there are three other campuses: Valletta, Marsaxlokk, Gozo. The University of Malta is a member of the European University Association, the European Access Network, Association of Commonwealth Universities, the Utrecht Network, the Santander Network, the Compostela Group, the European Association for University Lifelong Learning (EUCEN) and the International Student Exchange Programme (ISEP). The University of Malta has over 1500 bilateral agreements with universities across the world, from which 1100 are Erasmus agreements. |

Appendix B

| 1. How is performance appraisal used-symbolic vs rational performance appraisal | |

| 1.1 Is the performance appraisal system seen as a symbolic or rational. i.e., is performance appraisal used only to “symbolize” to external sites (e.g., government, funding agencies, etc.) that HEI act in rational, progressive, accountable manner but with any rational use for internal HR development purpose? | |

| Citation | Respondent |

| “You can’t talk about the system-what we do results from the parameterization and indicators that were shown there. There was also no comprehensive assessment attempt at a university other than parameterization.” | [S1] |

| “We are still in our infancy but all the tools created are moving towards the evaluation of scientific performance.” | [S3] |

| “We cannot say that we have a system-there are only elements on which this system can be built.” | [S4] |

| “We can’t talk about a systemic approach, we only have tools (…). Some scholars are evaluated every 2 years, others every year.” | [S6] |

| “The scientific assessment system is not effective, because the consequences of low scientific activity are poor or none. In the previous parameterization, we had several examples of N0 [authors: no publication during 4 years] at the faculty and there were no consequences.” | [U1] |

| “Universities are faced with a situation where the dismissal of an employee at a public university is a nightmare especially when trade unions are involved and appeals are lodged in court cases.” | [U2] |

| “I have experience in unsuccessful attempts to dismiss employees after repeated negative assessments of supervisors and students, it failed. Awards at the Faculty are given to everyone who published the book, so far without any gradation as to its scope and value.” | [U3] |

| “With such direct methods of employee appreciation, I don’t actually have it, there is no bonus, although partial compensation may be money intended for trips.” | [U4] |

| “The only evidence-based performance system is that of the promotions exercise for academic members of staff. Research output is one of the main three criteria for promotion from one grade to another.” | [C4] |

| “I am not aware that my university has other measures than those used for the promotion system of a resident academic.” | [C1] |

| “It is in my view academic progression through promotion that motivates researchers (by which I mean resident academics in this case). Because academic progression is not tied to a position (e.g., a Chair; headship, directorship) then it means that any academic can apply.” | [C1] |

| 2. Who is appraised-individual vs collective performance How possible it is to synchronise individual with collective performance? Is it a case of a silo mentality? | |

| 2.1 What kind of performance appraisal initiatives were introduced and implemented in HEI | |

| “The only motivation system is the promotion system. In the current collective agreement regulating employment by the university, academics need to publish a minimum number of research papers in order to be promoted to associate professor. This system has the advantage of encouraging academics to engage in research, however, it can be very disheartening for academics in high cost research areas to need the same number of publications to progress when there is no funding for consumables, equipment and research staff to enable them to generate sufficient, good quality data to publish. The lack of funding to pay publication charges (including open access) is also a serious limiting factor.” | [C5] |

| “I think that the most widely used performance systems are metric-based, pertaining to the quantity of peer-reviewed publications. Apart from this type of performance system, the quantification of lecturing hours and supervision is also used to gauge how much an academic ‘should be’ working. Moreover, consideration is taken of research projects/funding applications an academic is involved in; and any official position an academic holds and how the research output of academics helps universities go further up in rankings.” | [U2] |

| “Department is obliged to periodically (every year or two) to submit a self-assessment on the work it is doing, its publications, and initiatives in which it participates. There is also an evaluation of someone’s publication when s/he applies for a promotion (especially from Senior Lecturer grade to Associate Professor). Also, there is a system where funds (up to 50,000 euro) are given to academics for projects, after an evaluation of proposals is made.” | [C2] |

| “Financial motivators are used such as one-off scholarships which are a specific injection of cash and scholarship for high-score publications.” | [S1] |

| “There are mostly financial motivators: Rector’s award, scholarship for publications, but also non-financial-reduction of teaching hours for participation in the project.” | [S2] |

| “Times are such that non-financial motivators do not work, people want money for everything even for what they have inscribed in their duties. I see a problem here because I think that people who know the university ethos should work at the university.” | [S4] |

| “A certain novelty in our faculty is to be awarded only to high-ranking publications of international employees.” | [U3] |

| “I would see a researcher being stimulated and supported all the time and not only after financial award.” | [S1] |

| “There are very few incentives beyond promotion. Of course, once an academic reaches the top of the ladder, that incentive disappears. There used to be a bonus structure based on performance in three key areas including research that was abolished some 10 years ago.” | [U5] |

| 2.2 Is the performance appraisal individual or collective? | |

| “I evaluate that the effectiveness of performance solutions we have at 50%. We lack an individual approach to everyone, for now, we measure in groups, disciplines, faculties.” | [S6] |

| “With bonus it is weak, there is a tendency to similar remuneration in similar positions, unless someone earns in exact sciences teams often get money for projects, both external and statutory [authors: shared by the University] In social sciences, especially the humanities, the output, publications and grants are rather individual” | [U1] |

| “Mainly publications of individual scholars are awarded, customary monographs at our Faculty.” | [U2] |

| “At the department level, I encourage you to cooperate in teams, including inter-university and international ones...it is difficult to identify any methods of motivating these informal poses inherent in organizational culture”. | [U5] |

| 3. Why is performance management used–administrative vs developmental purposes? 3.1 Is there a tension between HEI and governmental agencies view on performance appraisal? | |

| “These best practices need to be used in order to stimulate a healthy academic culture where the university showcases its work and expertise. Such systems should not create the feeling among academics that they are in place in order to police their work; because such an approach will lead to the privileging of quantity over quality, where academics over time begin ‘playing the game’ to ensure they score highly on these performance systems, especially when these systems play an important role in being granted promotions”. | [C2] |

| “Limiting myself to only two KPIs (publications and participation in grants), which I have indicated, is insufficient for assessing the effectiveness of this system and we need more parameters to evaluate scientific progress, but our problem is that we are at an early stage of development of this approach because several decades before we operated differently.” | [S5] |

| “I believe that a managerial level should be introduced to manage teams or departments to relieve department managers from administrative and bureaucratic work. It should, therefore, be a Product manager-scientist responsible for a substantive input, idea, research and project manager supervising tenders, procedures, signatures, etc.” | [S3] |

| “At the management level, it would be good to have more knowledge about the academic achievements of the university...we need a good scientific reporting system”. | [U1] |

| 3.2 Is there an internal need for rational management by performance indicators or external pressure (e.g., government) forcing HEI to do performance appraisal? | |

| “New tools can be effective but it takes time to evaluate them. The proposals that are in various projects are focused on financial motivation but this motivator does not work logically-it is good for a short time.” | [S2] |

| “In addition to financial motivators, I think that the very motivator is the very nature of work (task time, quiet and stable work), and the desire to teach others that results from a sense of agency. Also, the ethos of the researcher and positioning himself in society in this category is an ennoblement and an opportunity for continuous development.” | [S6] |

| “The big problem in assessing scientific achievements is the differences between different sciences, humanists write books, artists create works, technical sciences implementations, and science creates papers in journals. The Ministry is trying to impose one frame, but this does not work out...hence the humanities protest committees and there is general frustration.” | [U2] |

| 4. How is performance appraisal perceiver by academic community–tool for performance improvement vs bureaucratic machine? 4.1 Which factors inhibit HEI in performance appraisal process? Are those internal or external factors? | |

| “The authorities are forcing more and more scientific bureaucracy, it was supposed to be de-bureaucratic, or rather the opposite, more and more scientific reporting.” | [U3] |

| “Practically the employee evaluation system was forced upon us by a ministerial act”. | [U12] |

| “All employee appraisal at the bill level is a bureaucratic obligation.” | [U14] |

| 4.2 Is performance appraisal focus on accountability and assessment only or on development of employee performance? | |

| “Employee appraisals do not have special developmental aspects because of a dominant friendly and collegial approach that does not encourage developmental talks based on documentation and evidence.” | [U15] |

| “There is also an evaluation of someone’s publication when s/he applies for a promotion (especially from Senior Lecturer grade to Associate Professor).” | U2 |

| “Researchers would be motivated if all their activities were taken into account in performance systems, i.e., not just their teaching hours and publications, but also their work in organizing/attending conferences; doing review or editorial work for journals; drafting funding proposals; contributions to industry; social engagement and public appearances; committee memberships; student satisfaction with their work.” | U2 |

References

- Aguinis, H. Performance Management; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez, Y.; Manzaneque, M.; Priego, A.M. Formulating and elaborating a model for the measurement of intellectual capital in Spanish public universities. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2017, 83, 149–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sułkowski, Ł. The culture of control in the contemporary university. In The Future of University Education; Izak, M., Kostera, M.Z., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017; pp. 85–108. [Google Scholar]

- Secundo, G.; Dumay, J.; Schiuma, G.; Passiante, G. Managing intellectual capital through a collective intelligence approach: An integrated framework for universities. J. Intellect. Cap. 2016, 17, 298–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alach, Z. The use of performance measurement in universities. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2016, 30, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birdsall, C. Performance management in public higher education: Unintended consequences and the implications of organizational diversity. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2018, 41, 669–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdlein, R.; Kukemelkb, H.; Turk, K. A survey of academic officers regarding performance appraisal in Estonian and American universities. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2008, 30, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallio, K.; Kallio, T.; Grossi, G. Performance measurement in universities: Ambiguities in the use of quality versus quantity in performance indicators. Public Money Manag. 2017, 37, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, L. Appraising academic appraisal in the new public management university. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2015, 37, 172–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sułkowski, Ł. Accountability of university: Transition of public higher education. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2016, 4, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haughney, K.; Wakeman, S.; Hart, L. Quality of feedback in higher education: A review of literature. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.; Heinesen, E.; Pedersen, L. How Does Public Service Motivation Among Teachers Affect Student Performance in Schools? J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2014, 24, 651–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; McDonald, B.; Park, J. Does Public Service Motivation Matter in Public Higher Education? Testing the Theories of Person–Organization Fit and Organizational Commitment Through a Serial Multiple Mediation Model. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2018, 48, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.; Brudney, J.; Coursey, D.; Littlepage, L. What Drives Morally Committed Citizens? A Study of the Antecedents of Public Service Motivation. Public Adm. Rev. 2008, 68, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefurak, T.; Morgan, R.; Johnson, R.B. The Relationship of Public Service Motivation to Job Satisfaction and Job Performance of Emergency Medical Services Professionals. Public Pers. Manag. 2020, 2020, 009102602091769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breaugh, J.; Ritz, A.; Alfes, K. Work motivation and public service motivation: Disentangling varieties of motivation and job satisfaction. Public Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 1423–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenabeele, W. The mediating effect of job satisfaction and organizational com-mitment on self-reported performance: More robust evidence of the PSM—Performance relationship. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2009, 75, 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naff, K.C.; Crum, J. Working for America: Does public service motivation make a difference? Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 1999, 19, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.; Wise, L. The Motivational Bases of Public Service. Public Adm. Rev. 1990, 50, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, L. Public service motivation and socialization in graduate education. Teach. Public Adm. 2016, 34, 284–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prysmakova, P.; Vandenabeele, W. Enjoying police duties: Public service motivation and job satisfaction. J. Police Crim. Psychol. 2019, 2019, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, N.C.; Brown, D.A. The illusion of no control: Management control systems facilitating autonomous motivation in university research. Acc. Financ. 2016, 56, 577–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellatly, L.; D’Alessandro, S.; Carter, L. What can the university sector teach us about strategy? Support for strategyversus individual motivations to perform. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 112, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ter Bogt, H.J.; Scapens, R.W. Performance Management in Universities: Effects of the Transition to More Quantitative Measurement Systems. Eur. Acc. Rev. 2012, 21, 451–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decramer, A.; Smolders, C.; Vanderstraeten, A.; Christiaens, J. The Impact of Institutional Pressures on Employee Performance Management Systems in Higher Education in the Low Countries. Br. J. Manag. 2012, 23, S88–S103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisi, A.S.; Murphy, K.R. Performance appraisal and performance management: 100 years of progress? J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrish, E. The Impact of Performance Management on Performance in Public Organizations: A Meta-Analysis. Public Adm. Rev. 2016, 76, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.R. Performance evaluation will not die, but it should. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2020, 30, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulakos, E.D.; Hanson, R.M.; Arad, S.; Moye, N. Performance management can be fixed: An on-the-job experiential learning approach for complex behavior change. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 8, 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleicher, D.J.; Baumann, H.M.; Sullivan, D.W.; Yim, J. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Performance Management: A 30-Year Integrative Conceptual Review. J. Appl. Psychol. 2019, 7, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tziner, A.; Rabenu, E. Beyond performance appraisal: To performance management and firm-level performance. Improv. Perform. Apprais. Work 2018, 8, 190–205. [Google Scholar]

- O’Boyle Jr., E.; Aguinis, H. The best and the rest: Revisiting the norm of normality of individual performance. Pers. Psychol. 2012, 65, 79–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.Z.; Akbar, S.; Budhwar, P. Effectiveness of performance appraisal: An integrated framework. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 510–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H. The effect of the performance appraisal system on trust for management: A field quasi-experiment. J. Appl. Psychol. 1999, 84, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbins, G.H.; Cardy, R.L.; Facteau, J.D.; Miller, J.S. Implications of situational constraints on performance evaluation and performance management. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1993, 3, 105–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, P.E.; Williams, J.R. The social context of performance appraisal: A review and framework for the future. J. Manag. 2004, 30, 881–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweedie, D.; Wild, D.; Rhodes, C.; Martinov-Bennie, N. How does performance management affect workers? Beyond human resource management and its critique. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 76–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, C.A.; de Nijs, W.F.; Hendriks, P.H. Secrets of the beehive: Performance management in university research organizations. Hum. Relat. 2010, 63, 1439–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritz, A.; Brewer, G.; Neumann, O. Public Service Motivation: A Systematic Literature Review and Outlook. Public Adm. Rev. 2016, 76, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decramer, A.; Smolders, C.; Vanderstraeten, A.; Christiaens, J.; Desmidt, S. External pressures affecting the adoption of employee performance management in higher education institutions. Pers. Rev. 2012, 41, 686–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, J.; Joyce, J.; Hassall, T.; Broadbent, M. Quality in higher education: From monitoring to management. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2003, 11, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobija, D.; Górska, A.M.; Grossi, G.; Strzelczyk, W. Rational and symbolic uses of performance measurement: Experiences from Polish universities. Account. Audit. Acc. J. 2019, 32, 750–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, P.; Jack, S. Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. Qual. Rep. 2008, 13, 544–559. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, V.T.; Porcher, R.; Falissard, B.; Ravaud, P. Point of data saturation was assessed using resampling methods in a survey with open-ended questions. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 80, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J.J.; Johnston, M.; Robertson, C.; Glidewell, L.; Entwistle, V.; Eccles, M.P.; Grimshaw, J.M. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol. Health 2010, 25, 1229–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldiabat, K.M.; Le Navenec, C.L. Data saturation: The mysterious step in grounded theory methodology. Qual. Rep. 2018, 23, 245–261. [Google Scholar]

- DeWalt, K.M.; DeWalt, B.R. Participant observation. In Handbook of Methods in Cultural Anthropology; Bernard, H.R., Ed.; AltaMira Press: Walnut, Creek, 1998; pp. 259–300. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, M.N. The Key Informant Technique, Family Practice; Oxfor University Press: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kawulich, B. Participant Observation as a Data Collection Method. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2005, 6, fqs-6.2.466. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, S.C.; Buckle, J.L. The space between: On being an insider-outsider in qualitative research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2009, 8, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainey, H.G.; Steinbauer, P. Galloping elephants: Developing elements of a theory of effective government organizations. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory Adm. Res. Theory 1999, 9, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingrams, A. Organizational Citizenship Behavior in the Public and Private Sectors: A Multilevel Test of Public Service Motivation and Traditional Antecedents. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2020, 40, 222–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bögner, I.; Petersen, J.; Kieser, A. Is it possible to assess progress in science?. In Multi-Level Governance in Universities; Frost, J., Hattke, F., Reihlen, M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 215–231. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Zwaan, B. Higher Education in 2040. A Global Approach; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Angiola, N.; Bianchi, P.; Damato, L. Performance management in public universities: Overcoming bureaucracy. Int. J. Prod. Perform. Manag. 2018, 67, 736–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, A.S. Advice from the Professors in a University Social Sciences Department on the Teaching-Research Nexus. Teach. High. Educ. 2013, 18, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leisink, P.; Steijn, B. Public service motivation and job performance of public sector employees in the Netherlands. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2009, 75, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, D.J. Public-service motivation: A multivariate test. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2000, 10, 713–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitsohl, H.; Ruhle, S. Millennials’ public service motivation and sector change: A panel study of job entrants in Germany. Public Adm. Q. 2016, 40, 458–489. [Google Scholar]

| Respondent Function | University | Respondent | Sex | Age | Scientific/Research Area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vice-Rector | Jagiellonian University (JU) | U1 | M | 60 | science, physics |

| Dean | (JU) | U2 | M | 48 | social sciences, strategic management |

| Vice-Dean | (JU) | U3 | F | 56 | data and information processing |

| Director of Institute | (JU) | U4 | F | 46 | social sciences, public management |

| Head of Department | (JU) | U5 | M | 47 | project management |

| Chair of Rector’s Office | Wrocław University of Economics (WUE) | S1 | F | 56 | research projects |

| Manager of the Scientific Research Service Centre | WUE | S2 | F | 39 | higher education; distance learning; mobility programs |

| Manager of the Project Management Centre | WUE | S3 | F | 45 | project management; EU projects |

| Dean | WUE | S4 | F | 54 | knowledge management; performance management; strategic management; |

| Vice-Rector for Finance | WUE | S5 | M | 44 | management accounting; controlling; performance management |

| Vice-Rector for Science | WUE | S6 | M | 53 | strategic management; organizational networks; business models |

| Director, Doctoral School | University of Malta (UM) | C1 | M | 47 | higher education; doctoral research; academic specialisation |

| Academic manager, Faculty of Arts | (UM) | C2 | M | 32 | higher education; faculty performance; academic specialisation |

| Academic manager, Faculty of Education | (UM) | C3 | F | 42 | higher education; faculty performance; academic specialisation |

| Director, Office for HR Management & Development | (UM) | C4 | F | 58 | higher education; HR performance; Training and Development |

| Academic manager, Faculty of Health Sciences | (UM) | C5 | F | 44 | higher education; faculty performance; academic specialization; EU Projects |

| Dean, Faculty of Science | (UM) | C6 | M | 52 | higher education; faculty performance; academic specialization; EU Projects |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sułkowski, Ł.; Przytuła, S.; Borg, C.; Kulikowski, K. Performance Appraisal in Universities—Assessing the Tension in Public Service Motivation (PSM). Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10070174

Sułkowski Ł, Przytuła S, Borg C, Kulikowski K. Performance Appraisal in Universities—Assessing the Tension in Public Service Motivation (PSM). Education Sciences. 2020; 10(7):174. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10070174

Chicago/Turabian StyleSułkowski, Łukasz, Sylwia Przytuła, Colin Borg, and Konrad Kulikowski. 2020. "Performance Appraisal in Universities—Assessing the Tension in Public Service Motivation (PSM)" Education Sciences 10, no. 7: 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10070174

APA StyleSułkowski, Ł., Przytuła, S., Borg, C., & Kulikowski, K. (2020). Performance Appraisal in Universities—Assessing the Tension in Public Service Motivation (PSM). Education Sciences, 10(7), 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10070174