Abstract

In the situation of a permanent change and increased competition, business ventures are more and more often undertaken not by individuals but by entrepreneurial teams. The main aim of this paper is to examine the team principles implemented by effective entrepreneurial teams and how they differ in nascent and established teams. We also focused on the relationship between the implementation of these rules by entrepreneurial team members and their evaluation of venture performance and personal satisfaction. The quantitative method was used: a list of nine items describing the principles important for the entrepreneurial teams’ collaboration was included in a questionnaire conducted in a group of 106 Polish entrepreneurs who run their businesses as members of entrepreneurial teams. The results of the research showed that all the collaboration principles included in the prepared scale are implemented by the tested entrepreneurial teams; in the case of two particular items, the obtained scores were higher in nascent teams. The correlation between principle implementation and venture performance as well as the correlation between principle implementation and entrepreneurs’ professional satisfaction was confirmed. In addition, the goal was to emphasize the importance of the entrepreneurial team’s collaboration due to its effectiveness, and propose the prepared scale as a tool for entrepreneurial reflective learning. Finally, statements by members of two entrepreneurial teams concerning team collaboration are presented to deliver case studies that can be used during entrepreneurship courses.

1. Introduction

A high level of market competitiveness, uncertainty and complexity stimulates entrepreneurs to create innovative projects and products to build their business positions. The main resource required for operating creatively and being agile is multidisciplinary knowledge integration. As a result, the potential usage of entrepreneurial teams in the development of new ventures is increasingly popular. Under conditions of limited resources, which is typical for new business ventures, the role of teams in entrepreneurial projects is unarguable [1]. The team can compensate for individual weaknesses and utilize financial, mental and emotional resources together with talent, experiences and skills to strengthen the social capital of the enterprise [2]. Entrepreneurial teams are more effective in responding to complexity and changes in the environment, which results in teams better overcoming challenges, troubles and crises.

New firms established by entrepreneurial teams more often grow faster and operate successfully on the market [3], especially on the global and virtual market [4]. When working in teams, people feel support and fulfil their affiliation need, which increases their satisfaction and reduces the stress level [5]. This results in the fact that more than 80% of ventures are team-based [6].

There are also some threats that are associated with venture creation by an entrepreneurial team: interdependence of responsibility for vision implementation, social loafing, or a tendency to maximize personal profits by individual shareholders at the expense of team effects [7]. Furthermore, it is said that 50% of new team ventures fail due to collaboration problems in entrepreneurial teams [8]. That is why the way the members of entrepreneurial teams operate, and the way they communicate, make decisions and share the profit is crucial for their performance and the venture’s success. Answering questions about the most important entrepreneurial team collaboration principles implemented by effective teams, as well as preparing a tool to measure how much they are implemented in an entrepreneurial team, seem to be very useful for entrepreneurial education.

Despite all the advantages of entrepreneurial teams, the subject has rarely been investigated in research projects conducted in Poland. The individual entrepreneur approach is much more common when we consider education programs focusing on entrepreneurial competencies too. Polish students usually do not associate setting up their own company with team activity [9] and are not conscious of the importance of the entrepreneurial team mental model for venture performance [10].

The main aim of this paper is to examine the team principles implemented by effective entrepreneurial teams and how they differ in nascent and established teams. We also focused on the relationship between the implementation of these rules by entrepreneurial team members and their evaluation of team effectiveness, measured by two factors: venture performance and personal satisfaction. In addition, the goal was to emphasize the importance of entrepreneurial team collaboration due to its effectiveness and propose the prepared scale as a tool for entrepreneurial reflective learning. Finally, the statements of members of two entrepreneurial teams concerning team collaboration are presented as the case of possible best practices for entrepreneurship courses.

The article is divided into three main parts. The first addresses theoretical issues related to collaboration in entrepreneurial teams and their effectiveness, as well as its relation to satisfaction. Many of the literature sources indicate that the relationship (direct and indirect) between an entrepreneurial team and new venture performance were confirmed and pertain to such characteristics as team members’ behaviors, attitudes, orientation and their composition in the entrepreneurial team [11]. However, the influence of internal processes on venture business success is still not fully recognized [1], and research studies conducted in the context of Polish entrepreneurial teams remain scarce.

The second part presents the results of research carried out in a group of Polish entrepreneurs who run their businesses as members of entrepreneurial teams (nascent or established) in Poland. The primary purpose of the research was to examine team principles implemented by effective established entrepreneurial teams and by nascent entrepreneurial teams. The next aim was to test the relationship between entrepreneurial teams’ principle implementation and two factors of teams’ effectiveness: venture performance and members’ satisfaction. The quantitative method based on the created entrepreneurial teams’ implementation of collaboration principles (ETICP) scale was used to test the research hypotheses. Research findings advance the current understanding of entrepreneurial team collaboration as well as allowing us to propose practical suggestions to be used in entrepreneurial teams’ operations and entrepreneurial education.

The third part refers to the implication of the obtained results for entrepreneurial education. The reflective learning context is presented to introduce the entrepreneurial team’s principles survey as a tool to discuss, measure and improve team members’ relationships. Two examples of effective entrepreneurial teams are also presented through the lens of team principles to illustrate their implementation in practice. The possibility of using them as examples of best practice is described.

The structure of the article includes seven sections. The Section 1 is a brief introduction to the considered problems. The Section 2 defines entrepreneurial teams (Section 2.1), presents the main features of nascent teams in comparison to established ones (Section 2.2) and discusses entrepreneurial teams’ effectiveness factors: performance and satisfaction (Section 2.3). The Section 3 is dedicated to research methods and research hypotheses. The ETICP index and the ETICP scale is described here. The research results are presented in Section 4 and their discussion is included in Section 5. Practical implications for entrepreneurial team operation, as well as entrepreneurial education, are presented there. Section 6 includes inspirations for reflective entrepreneurial education based on the ETICP scale and two case studies. The Conclusion indicates limitations of our research and proposes future research avenues.

2. Entrepreneurial Team

2.1. Entrepreneurial Team Definition and Collaboration Principles

An entrepreneurial team is defined as a group of entrepreneurs who make a joint decision to start a new venture, and act together during all stages of the entrepreneurial process: identifying an opportunity, defining the goal and the model of the venture, assessing the need for various resources, acquiring necessary resources, launching the venture, managing its development and sharing profits [12,13]. It is also understood as a ‘top team of individuals who are the most responsible for the establishment and management of the business’ [8]. Cole, Cox and Stavros [14] emphasize that two individuals are enough be called an entrepreneurial team only if they hold a share in a company and make strategic decisions. Entrepreneurial team members hold an ownership position and are motivated to use their human capital for their organization’s performance and growth [5].

The factors that influence entrepreneurial team membership are equity stake, founder status and strategic decision making [8]. The definition of an entrepreneurial team proposed by Schjoedt and Kraus [15] emphasizes the most important features determining the venture success: ‘An entrepreneurial team consists of two or more persons who have an interest, both financial and otherwise, in and commitment to a venture’s future and success; whose work is interdependent in the pursuit of common goals and venture success; who are accountable (...) for the venture; who are considered to be at the executive level with executive responsibility in the early phases of the venture, including founding and pre-startup; and who are seen as a social entity by themselves and by others’.

To operate in an efficient manner, entrepreneurial teams need to apply all the rules concerning other types of teams, like shared goals, complementary skills, commitment to a common purpose, a set of performance goals, and an approach for which team members hold themselves mutually accountable [16]. The main difference between organizational teams (like project teams or functional teams) and entrepreneurial teams is the context in which they operate. In the case of an entrepreneurial team (which create the new venture), it is much less established because social rules are undefined, team roles are ambiguous, the organization is still evolving, and the team members are fully responsible for managing the venture [17]. More strategic freedom and more internal structure provoke problems in team cohesion and decision-making processes [18]. This triggers the need to identify and access principles regulating entrepreneurial team collaboration.

One of the frameworks that are useful to describe aspects of collaboration important for entrepreneurial teams is the strengths, opportunities, aspirations, and results (SOAR) that define the effective collaborative strategy as a “strengths-based and opportunity-focused inquiry on the aspirations and desired results for the team” [14]. SOAR authors have proved that emotional intelligence and open dialogue are vital for entrepreneurial team performance and the main principles affecting team members collaboration should be:

- Identifying members’ strengths and aspirations to use their competencies in the venture-developing process;

- Identifying opportunities together to achieve shared strategic goals;

- Collaborative dialog concerning new venture strengths and possible opportunities assessments;

- Inclusive conversations about the company’s vision and planned actions.

Entrepreneurial team members need to understand each other’s areas of expertise as well as preferences, strengths and weaknesses in order to structure their responsibilities and complement each other. The manner in which the team knowledge is organized and distributed is the element of team cognition—an emergent state that allows the team to make assessment and decisions and influences team processes [17]. There are two kinds of these processes: taskwork processes (decision-making, problem-solving, coordinating) and teamwork processes (motivation, conflict resolution, team rules, support and trust).

Most of the researchers point out at least a few of them as the entrepreneurial team performance triggers. Vyakarnam et al. [19] identifies motivation based on clear goals and shared vision mixed with entrepreneurial flair, being focused on strategy, and relationships based on trust as the main venture success drivers. The high level of each owner’s motivation prompts them to voluntarily invest their time and engage in actions which benefit their venture [20]. The members debate and discuss their decisions, share previous experience and knowledge, and share leadership that increases coordination and cooperation. The power of each team member should not be the main motivation to join the team, and the power distribution should result from the fit between a person and a given situation, and should be re-distributive. When power depends on the stake in the firm and promotes one of the owners, it causes conflicts and decreases other members’ interest in long-term results [15]. Shared commitment and shared accountability lead to the consideration of all members’ opinions and generation of different alternatives in the process of decision making. This stimulates open communication of each person’s expectations and perceptions. One’s owner having too much power can promote conflict, which negatively affects the venture launch. Divergent venture visions can also result in frictions, and if they are to positively influence the team’s results, the professionalization of the decision-making process is required [18]. Shared cognition limits the negative impact of conflict on team cohesion, consensus decision-making, members’ satisfaction and, finally, venture success [21].

Harper [3] concludes that three conditions are necessary to format an entrepreneurial team: bounded structural uncertainty (acceptance of risk connected with venture profit mixed with rules and norms defining property rights and others), common interest (collaboration approach in problem solving) and strong interdependence (a common belief that team members can achieve goals together, not on their own, and joint decision-making). Schenkel and Garrison [4] mention a list of conditions influencing entrepreneurial team success and call them relational capital:

- Trust, friendship and respect are the rules of collaboration and allow to share knowledge and experiences openly;

- Proactive engagement in strategic activities is typical for all the members of an entrepreneurial team;

- All the members have the necessary personal resources to achieve business success, and are able to recognize them and share them to meet the market needs.

The members’ knowledge and skills seem to be the critical elements of business opportunity recognition [22] as well as vision and venture development [18]. The set of principles that regulate entrepreneurial team members’ contribution, engagement, roles, responsibilities and profits is a crucial part of team relationships. The main aim of this paper is to examine the team principles implemented by effective experienced entrepreneurial teams and how they are introduced by nascent entrepreneurial teams. We expect some differences because of the uniqueness of the characteristics of nascent teams.

2.2. Nascent Entrepreneurial Teams

A nascent entrepreneur is defined as a person who has just discovered a business opportunity and completed at least one business gestation activity [23], or who has been active in trying to start a new business in the past 12 months [24] but has not made a profit yet. In the context of an entrepreneurial team, the definition is not so clear, although the very first stage of entrepreneurial team formation is widely discussed [25]. Sirén et al. [26] describe a nascent entrepreneurial team as a “team which consists of individuals who are taking tentative steps towards firm formation”, and listed the main features of nascent entrepreneurial teams:

- Scarcity of time, money and human capital;

- Lack of structure and decision-making routines;

- High level of uncertainty and ambiguity;

- High interdependence;

- Limited formalization of roles, tasks and responsibilities among team members;

- Affective nature (affective events take place and stimulate intense positive and negative emotions);

- Possibility for all team members to emerge as leaders;

- Need to establish team roles and norms.

This fits the psychological model of new team formation which suggests that members of new teams are likely to be at a stage when affective and cognitive conflicts are not yet prevalent, and thus individual team members may not yet be able to benefit from having established a common way of thinking [27]. They are much more focused on opportunity recognition and the formulation of team norms [28]; they need to develop a shared understanding of the context and requirements, and develop team cohesion, which is crucial for team members’ satisfaction.

There are two main models of entrepreneurial team origin: the first one—specialization- or resource-related—describes an individual nascent entrepreneur who searches for co-owners to select the ones who can enrich human capital by diversified knowledge and expertise. The second model, called coordination strategy, presents the entrepreneurial team as a group formed previously to work on a project, a group of friends or family members who have similar interests and like each other. Both strategies are not mutually exclusive, both can be linked to high performance levels, and both generate some threats. The specialization strategy results in trust based on members’ expertise, while the coordination strategy facilitates effective communication and shared vision [25]. The coordination strategy benefits from previous interpersonal experiences and mutual sympathy. However, some research studies place emphasis on the negative consequences of the nascent entrepreneurial team’s density [29] and point out that proximity and affectivity among members limit the constructive diversity and external social capital. Both strategies influence team processes, e.g., if the criterion of partner selection is the amount of resources (e.g., money) she or he is able to contribute, the risk of moral hazard appears when the contribution is not equal. This requires equity sharing rules that are usually an element of shareholders’ contract that defines partnership in an entrepreneurial team. Ben-Hafaïed and Cooney [30] call the main decision that needs to be made by nascent entrepreneurial teams the “Three Rs” rule, concerning relationship, roles and reward. In combination with the distribution of power and strategic decision-making, they are crucial for a strong team entity.

In our study, we define a nascent entrepreneurial team as a group of two or more people who have made a joint decision to start a new venture together, who have acted together during the initial stage of the entrepreneurial process for no longer than six months, feel responsible for the establishment and management of the business, and are motivated to use their human capital to develop the company. Because the teams are at the initial phase of their development, we expect that some of the rules may not be implemented yet.

2.3. Entrepreneurial Team’s Venture Performance and Satisfaction

There are many models describing team effectiveness, like Hackman’s Normative Model, Gladstein’s Model [31] or Campion’s Synthesis Model [32]. They discuss the input influencing team effectiveness but also define the main criteria used to assess the output, like team performance and members’ satisfaction. Team effectiveness is defined as a multidimensional construct consisting of three interrelated dimensions: the output of the team, the long-term viability of the team as a performing unit, and the impact of team experience on individual team members [31]. This definition also suggests that when assessing team effectiveness, we need to measure not only the results but also team members’ satisfaction. In this study context, they need to be explained in the case of entrepreneurial venture creation and management. Murphy, Trailer and Hill [33] have analyzed the empirical entrepreneurship literature to find out the main criteria of successful entrepreneurial performance of new ventures and the variables used to measure performance. The most-used ones include efficiency, growth, profit, size, liquidity, success/failure dimension, market share and leverage. The authors stressed the need to use a multidimensional measurement of entrepreneurial venture assessment, including financial and non-financial aspects. To study entrepreneurial venture performance, Mayer-Hauga, Readb and Brinkmaneec [34] used six categories of measures:

- Growth (e.g., asset growth, business growth over the last three years, growth in employees, market share growth, net profit growth rate);

- Scale (number of employees);

- Sales (e.g., log of sales, sales per employee, revenues);

- Profit (e.g., income, net income, profit, after-tax profit);

- Other financials (e.g., cash flow, liquidity, return on asset, shareholder return);

- Qualitative performance (e.g., financial management, market share, alliance success, progress performance, firm survival, perceived performance, performance versus competitors).

Wincent and Ortqvist [35] sum up: “Venture performance represents the ultimate measure of the strength of any new venture or organization. It includes indicators such as sales, market share, customer satisfaction, and return on assets when compared with other organizations.” and point it out as one of two elements of entrepreneur’s rewards together with entrepreneur’s satisfaction with profits, engagement, or aspiration.

The concept of entrepreneurial satisfaction is derived from a more general construct of job satisfaction that is defined as “a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experiences" [36]. It has often been studied as a predictor of workers’ motivation and commitment as well as absenteeism and other responses to job or employer [37,38,39]. Studies on job satisfaction primarily concentrated on research among employees rather than among entrepreneurs. However, studies carried out among self-employed individuals have repeatedly shown that they are more satisfied with their job than employees [40,41,42]. Currently, it is believed that satisfaction is not only connected with individual entrepreneurial success but, more importantly, because entrepreneurial satisfaction is influenced by venture performance, the level of job satisfaction can be a key measure of it.

Trying to answer the question of why self-employed have higher satisfaction rates than employees, researchers most frequently suggest higher autonomy, independence and procedural freedom of entrepreneurs [43,44]. These results apply only to the self-employed who wanted to take this route. If employees were forced into self-employment (necessity entrepreneurs), they often expressed a desire to return to paid employment [45].

What is interesting, in the context of the study presented in this paper, is the fact that teamwork is one of the factors related to job satisfaction [46,47,48]. However, job satisfaction, in this case, is determined by various factors, including the team composition, group processes and the nature of the work [49]. Breugst, Patzell and Rathgeber [50] showed that the perception of justice within the team has a strong relationship with the level of satisfaction.

Based on the above analysis of the literature, the question about the satisfaction of the members of the entrepreneurial team arises. If the satisfaction of an individual entrepreneur results from a sense of autonomy and independence, will it also occur in the context of cooperation in the entrepreneurial team? Is the level of professional satisfaction of entrepreneurial team members related to implemented teamwork principles? Does it depend on team experience? The presented research also aimed to answer these questions. We expect that the relationship between team role implementation and team effectiveness (measured by team performance and team members’ satisfaction) in nascent entrepreneurial teams is significant, but it should be stronger in established teams.

3. Methods

The main aim of the present research was to examine team principles implemented by effective established entrepreneurial teams and by nascent ones. The level of entrepreneurial teams’ implementation of collaboration principles is expressed by an ETICP index ranging from 1 (poor) to 5 (the highest level). Firstly, we needed to prepare a scale to test the ETICP index (called the ETICP scale). Secondly, we focused on the relationship between collaboration principles’ implementation and team effectiveness measured by two important indicators: venture performance and personal satisfaction. Starting from an in-depth analysis of the literature, we tried to investigate the relationship between the extent to which team principles are followed by entrepreneurial teams (i.e., the ETICP index) and venture effectiveness. We also expected this relationship to be stronger in established entrepreneurial teams where the principles can be clearer and tested in practice.

Taking the above considerations into account, we formulated three hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1.

The collaboration principles measured by ETICP scale are implemented by entrepreneurial teams regardless of their experience, but the level of ETICP index is higher in established entrepreneurial teams.

Hypothesis 2.

There is a positive relationship between the implementation of entrepreneurial team collaboration principles and entrepreneurial team performance perceived by their members.

Hypothesis 3.

There is a positive relationship between the implementation of entrepreneurial team principles and team members’ satisfaction.

The research was conducted with a group of 106 entrepreneurs who run their businesses as members of entrepreneurial teams. The research presented in the current paper is a part of a larger national project. We conducted our study on two groups of entrepreneurial teams—experienced teams whose members collaborated for at least three years (40 entrepreneurs) and nascent teams that were no older than six months when they took part in the study (66 entrepreneurs). In Table 1, descriptive statistics pertaining to our sample of entrepreneurial teams are presented.

Table 1.

Descriptives—entrepreneurial teams.

For the purpose of this article, we considered the firm’s survival of at least 3 years as a proxy for the company’s success, as the probability of a firm’s failure after that period might drop significantly [51]. We employed different means in the process of the sample recruitment. These included: contacting companies listed in a purchased professional database, contacting start-up incubators and technology parks operating in the metropolitan area, contacting university spin-offs, informing alumni and post-graduate and executive students about the project and the snowball technique. Due to the fact that a variety of different activities was performed, our sample might be considered quite heterogeneous as it consists of entrepreneurial teams of different backgrounds and history. Each of the participants individually filled out an online survey. Moreover, the data collection process took place in two stages—the second stage took place several weeks after the first one. In the first stage, data pertaining to teams’ collaboration principles were collected. In the second one, participants answered questions about their satisfaction and the company’s performance.

The aim of the first step of the research was to prepare the ETICP scale. We created the list of nine principles crucial for entrepreneurial team collaboration—they are presented in Table 2. Each of the items corresponds with an important rule which may be introduced to organize operations and facilitate collaboration within the team. Items were created and selected based on the analysis of sources described in the literature review included in the second section of this paper.

Table 2.

Collaboration principles—items.

For further analyses, we verified the internal reliability of the ETICP scale using Cronbach’s alpha. It reached a very high level (Alpha = 0.94) which proved the ETICP scale’s internal consistency and its reliability. The ETICP index, which indicates the level of implementation of collaboration principles, was created by calculating the mean score of answers to all nine items, separately for each participant. A 5-point Likert scale anchored at 1—“this statement does not refer to our company’ to 5—“this statement refers to our company very much’ was used.

As was mentioned earlier, in the second stage of the research, the company’s performance and the team member’s satisfaction were measured. Both these dimensions are perceived in this paper as dimensions of entrepreneurial team effectiveness. We created an eight-item firm performance scale. Again, it was based on the previous research described in the second section of this paper. It included items pertaining to financial aspects of performance (e.g., our company’s investments bring expected revenue), to company’s growth (e.g., we increase the number of employees or we plan to increase it) as well as its reputation (our company enjoys a reputation among customers). Participants were providing their answers using a 5-point Likert scale. The scale’s internal reliability level was calculated, and as it was high (α = 0.86), a single measure of performance was created by calculating the performance scale’s mean score for each participant.

In order to measure the entrepreneurial team members’ satisfaction, a six-item scale was used. It included statements pertaining directly to satisfaction (e.g., running the company gives me satisfaction.) but also to a sense of personal fulfillment (e.g., thanks to my work I have the time to fulfill my dreams.). Again, a 5-point Likert scale was used and a single measure was calculated after obtaining a satisfactory level of scale reliability (α = 0.77).

4. Results

4.1. Implementation of Collaboration Principles

The first stage of the research was to assess the ETICP index for established and nascent teams. The descriptive statistics—mean and standard deviation—for each item are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Collaboration principles—descriptive statistics.

The mean score in the entire sample of the implementation of team collaboration principles measured by ETICP index was 4.18 and can be assessed as high. All nine principles are implemented by examined entrepreneurial teams regardless of their experience. The lowest (below 4.0) total results refer to members’ involvement in running the company and managerial roles’ division. These results remain at a medium-high level. The highest result (4.47 out of 5) refers to task distribution based on team members’ competencies, but it needs to be analyzed separately for each of the study groups.

The comparison between members of experienced and nascent teams was conducted using the Mann–Whitney U test. It showed that the significant difference concerns two items, no. 1 (z = −2.41, p = 0.02) and no. 8 (z = −2.51, p = 0.04). Both items relate to members’ competencies, and their results were much higher in the group of nascent teams (they are bolded in Table 3). The mean results of the implementation of collaboration principles in the nascent entrepreneurial team were also higher, but the difference is not statistically significant (z = 0.11, p = 0.9).

The hypothesis H1: The collaboration principles measured by ETICP scale are implemented by entrepreneurial teams regardless of their experience, but the level of ETICP index being higher in established entrepreneurial teams was partially supported. The achieved results confirm the implementation of all nine principles included in ETICP scale in both study groups. The ETICP index reached a high level in both types of entrepreneurial teams. However, our assumption regarding higher results in established entrepreneurial teams was not confirmed. Respondents operating in nascent entrepreneurial teams assessed the implementation of two teams’ collaboration principles as higher than the established group.

4.2. Relationship between Principle Implementation and Team Effectiveness

Descriptive statistics of scales measuring members’ assessment of company performance and their satisfaction, prepared using the described procedure, are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Company performance and team members’ satisfaction—descriptive statistics.

Research participants assessed their companies’ performance as average. The score of established entrepreneurial teams is significantly higher than that of nascent ones (Mann–Whitney U test; z = 3.71, p < 0.001). Team members’ satisfaction does not differ significantly between both groups and, overall, its level is quite high among study participants.

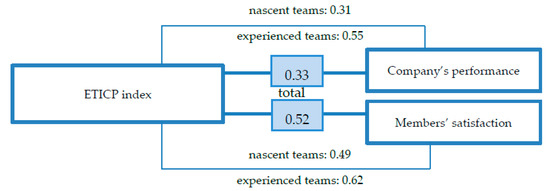

In order to verify our hypotheses pertaining to the relationship between the level of ETICP index and the company’s performance as well as team members’ satisfaction, the Spearman correlation coefficient was computed. Statistically significant positive relationships were found:

- Between ETICP index (total result) and the company’s performance (total result) (rs = 0.33, p < 0.01);

- Between ETICP index (total result) and entrepreneurial team members’ satisfaction (total result) (rs = 0.52, p < 0.05).

Therefore, hypotheses H2 and H3 were supported. The ETICP index seems to be connected more strongly to the entrepreneurial team’s member satisfaction. However, there is also a positive relationship between ETICP index and the team’s performance.

Additionally, the relationship between the implementation of entrepreneurial team principles and entrepreneurial team performance and members’ satisfaction were analyzed separately in groups of experienced and nascent entrepreneurial team members. The obtained results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Correlation between ETICP index and team members’ satisfaction in experienced and nascent entrepreneurial teams (p < 0.05).

As shown in Table 5, a positive correlation between the ETICP index and team effectiveness was confirmed in the case of both types of team. Hypotheses H2 and H3 were supported. The results regarding established teams confirm a moderate positive relationship between ETICP index and both dependent variables. When it comes to nascent teams, the relationship between ETICP index and members’ satisfaction reaches a moderate level, but in the case of company’s performance, the relationship is weak (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Correlations between ETICP index and: company’s performance and team members’ satisfaction.

To further verify the relationship between the level of ETICP index and satisfaction and performance in mature and nascent teams, an additional statistical analysis was performed. It involved the Scheirer–Ray–Hare test, which is a non-parametric equivalent of the multivariate ANOVA. The following results were obtained:

- There were no significant differences in the level of satisfaction depending on the type of the company (mature versus nascent) (H = 1.77, p = 0.18);

- Significant differences in the satisfaction level were found depending on the ETICP level (H = 17.40, p < 0.05), regardless of the type of company;

- No significant interaction was found between the two independent variables (company type and ETICP level) in relation to satisfaction (H = 1.10, p = 0.78);

- There were significant differences in the level of performance evaluation depending on the type of company (H = 12.55, p < 0.05);

- Significant differences were found in team performance depending on the ETICP level (H = 8.19, p < 0.05);

- No significant interaction was found between the two independent variables (company type and ETICP level) in relation to performance (H = 1.8, p = 0.61).

These results confirmed the revealed positive relationship between the implementation of team collaboration principles and the effectiveness of entrepreneurial teams and team members’ satisfaction. Additionally, they support the usefulness of the employed ETICP index.

5. Discussion

5.1. Study Discussion

The interactions in entrepreneurial teams were discussed in a relatively small number of articles concerning entrepreneurial team performance [6], and they were focused on the team’s diversity, learning processes, conflict resolution, and leadership. Some of them have proved the importance of social interactions for the success of new ventures. Our aim was to investigate the principles important for the entrepreneurial team collaboration process. The nine items included in the ETICP scale were validated and the high reliability of the scale was confirmed. We introduced the ETICP index as the measure of entrepreneurial teams’ implementation of collaboration principles.

Our research has confirmed that the tested entrepreneurial teams implemented all the collaboration principles included in the prepared scale. Contrary to our assumptions, the implementation of teams’ collaboration principles was generally not different in the two analyzed groups. In the case of two particular items of our scale, the obtained scores were even higher in nascent teams. This confirms the Ben-Hafaïed and Cooney [30] statement that the rules concerning the relationship, roles and rewards in combination with the distribution of power and strategic decision making are crucial for teams’ operations. The differences discovered between nascent and experienced teams may arise from the characteristics of nascent teams. The principles concerning human capital contribution are very important here because each member’s skills and expertise could be the selection criterion used in the team. This is particularly important when a nascent team’s origin is based on the specialization model [25], when co-owners’ expertise is the most vital criterion for the partner’s selection. High human capital can also be used to reduce uncertainty, ambiguity and risk connected to the scarcity of resources, which are said to be primary determinants of nascent entrepreneurial teams’ operations [26]. Human capital scarcity can be the reason why their members pay attention to the division of tasks according to competencies and care more about each member’s contribution to business development.

Hackman’s Normative Model [31] criteria were used to measure team effectiveness: team performance and members’ satisfaction. To assess venture performance, we have chosen Murphy, Trailer and Hill [33] model and the satisfaction scale was based on Lange [44], Kantonen and Palnoroos [46] methods. Our study contributes to the entrepreneurship literature by introducing entrepreneurs’ satisfaction as the measure of business venture teams’ effectiveness.

The relationship between principles’ implementation and venture performance as well as the relationship between principles’ implementation and entrepreneurs’ professional satisfaction was confirmed. Nascent teams are at the initial phase of their company existence and their profits, reputation, or plans for employment are very low or none (which is confirmed by team members’ assessments). Performing in a coherent, conflict-free and supportive team can be the main source of members’ satisfaction [49], which makes collaboration rules very important. For established teams, whose members assessed companies’ performance as better, it can be the main reason behind their professional satisfaction. Team cooperation rules, however, are correlated with the company’s performance. The transparency of roles and the division of responsibilities, as well as profit distribution and each shareholder’s engagement, are crucial for fluent collaboration and provide an opportunity to focus on business tasks rather than setting team collaboration standards. If they are established earlier and work well, they can be a part of the company’s culture, and influence its performance.

Based on these results, it can be stated that the importance of introducing appropriate entrepreneurial team cooperation principles is not just a matter of effectiveness but also of satisfaction. Additionally, high consistency in the perception of the implemented rules based on trust can be, in our opinion, a characteristic feature of effective entrepreneurial teams.

5.2. Practical Implications

Our findings have important implications for practice. First, members of entrepreneurial teams may benefit from a better understanding of collaboration principles importance for their satisfaction and venture performance. As the economic factors and entrepreneurs’ networks are often discussed as the main determinants of companies’ success, social relationship within entrepreneurial teams are taken for granted and perceived as well established and less meaningful. Our findings support their importance for new and experienced teams. For nascent teams, it needs to be clear the rules concerning the identification of members’ strengths and using them in the venture-developing process [18] can be used to reduce the limitations of resources and for dealing with a high level of uncertainty. The principles referring to co-owners’ contributions and profit distribution should not be undervalued. The implementation of cooperation principles by members of the nascent team can be an important source of motivation in the initial stage when income is not sufficiently high to satisfy entrepreneurs. The established teams need to consider the collaboration principles, as they can be their venture’s success driver [19]. If they are not settled clearly, partners’ roles are not well defined and their contribution is not equal, which leads to conflicts and can limit the collaborative approach, which is vital for business development [3]. The principle concerning using team members’ competencies was implemented on the lower level in the established teams. The motivation to perceive other co-owners as suppliers of important resources for the venture can be one of the remedies that protect mature entrepreneurial teams against the collapse of their company related to collaboration problems [8].

Secondly, our findings and ETICP index can be widely used in entrepreneurial education processes. They can address the needs of three potential groups of recipients: established entrepreneurial teams, nascent entrepreneurial teams and graduate students. Collaborative reflective learning can be implemented in all three groups [52]. The members of established entrepreneurial teams can learn on the basis of their own experience and use the ETICP scale to evaluate their collaboration processes, and assess their strengths and weaknesses concerning the distribution of competencies, responsibilities, power and company’s profits. The possible gaps in the team’s relationship can be clarified, and improvements can be implemented. Reflection helps to clarify intentions and possible consequences, to evaluate and synthesize primary entrepreneurial experience to develop knowledge [53]. Self-assessment on the basis of the ETICP scale allows to diagnose a particular team’s needs and can be used for a highly personalized consultancy service. The development of the team’s collaboration can be beneficial for venture performance and for team members’ satisfaction.

Nascent co-owners should also be reflective on the processes within the team they conceived to develop a business venture. At the initial phase of their collaboration, they are focused on filling the gaps related to funding, resources, structure, decision making methods and roles. Some of the nascent teams start with nothing more than the raw talents and determination of team members. This places the principles concerning co-owners’ competencies among the most important ones. The reflective learning process supported by the ETICP scale can be used to influence the founding team and facilitate company culture development. Reflections on the relationship between the implementation of collaboration principles and members’ satisfaction can strengthen teams’ awareness of their importance for each person’s well-being and the company’s progress.

Elements of entrepreneurial team collaboration are rarely included in the entrepreneurship courses delivered for university students. Some of the principles that we discovered were implemented by effective entrepreneurial teams are covered during team building, team management and leadership courses. In the case of business venture creation, an individualistic approach prevails. We propose that the results presented in this paper and the questionnaire we have created can be used to complement students’ knowledge and skills regarding the process of entrepreneurial team development and its effectiveness. Reflection as a mental process that engages deep thinking and can explain and understand experience is well known as a method used in entrepreneurial education. It pertains to metacognition, an element of students’ self-regulation process [52]. In university students’ case, the reflective learning can be based on graduates’ participation in entrepreneurial projects, the experience of seasoned entrepreneurs and support from a teacher. The ideas on how to implement our findings and ETICP scale in graduates’ education are presented in the next chapter. They are supplemented by two examples of effective entrepreneurial teams’ collaboration case studies.

6. Educational Inspirations

Two recommendations are presented: the first one proposes that the ETICP index and our questionnaire can be used as a tool for entrepreneurial reflective learning. The second one includes an example of best practices based on statements of members of two experienced entrepreneurial teams linked to nine collaboration principles.

Learning activities based on experience need to be completed with proactive, reflective sessions, self-assessment, and the possibility to compare experiences to different concepts. This process needs to be conscious and focused on changing understanding, perception, and future behavior [54]. Reflective learning can be individual or collaborative when people can learn on the basis of their own experience and the experience of a more experienced person or support of a coach. A facilitator’s or teacher’s role is to guide students during the process of reflective learning as well as to use selected methods that trigger reflection, like self-awareness activities, writing letters or blogs [52,53]. Modern technologies are very useful in reflective learning. Applications that students are familiar with can be used as multi-level support for reflective learning: they can support collecting data from the experiences, to structuralize them, they can include tips or questions triggering the self-assessment and reflection process, allow to share the experiences and reflections with other students or, finally, help to plan future actions based on reflections [54].

We propose that the ETICP scale can be used for measuring.

The implementation of entrepreneurial team collaboration principles as a tool for entrepreneurial reflective learning:

- Self-assessment tool (after entrepreneurial team task realization)—the items of the questionnaire can be made available online (e.g., Mentimeter app can be used) to allow students to assess their experiences of collaboration during entrepreneurial tasks or simulations. The answers of each team member can be compared with the opinions of other team members, they can be discussed in the context of the research results presented in this article, and a shared plan for future team collaboration can be prepared;

- Logs triggers—the items of the questionnaire could be also used as the points the students must take into consideration while collecting logs about the entrepreneurial team collaboration process and effectiveness. All logs need to refer to nine principles included in the questionnaire and some checkpoints need to be pointed out to stop the collaboration process, discuss the logs and look for possible improvements in team operations. At the end of the project, an assessment of the ETICP index can be conducted according to the questionnaire, and the results should be discussed. Another final step can be to write an essay to summarize the team processes on the basis of the implementation of principles and their influence on team effectiveness.

Another active learning method that is widely used in entrepreneurial (and not only entrepreneurial) education is the case study. It is usually a description of a real situation which allows students to analyze the challenges, decisions and opportunities faced by the described persons or companies, and provokes students’ critical thinking in complex contexts [55]. A case study includes not only the necessary data but also open questions or problems to be solved. Case studies promote group discussion, motivate students to find out connections between academic knowledge and real-life conditions [56]. To support learning about collaborative entrepreneurship, we propose two short case studies. The members of the described entrepreneurial teams participated in the quantitative research, and their results in the questionnaire were extremely high and congruent. Both teams are established teams, family businesses, and have achieved business successes. Members of the entrepreneurial team were asked to participate in an interview to describe their team collaboration. The main features of each team are presented in Table 6; the names of the companies were kept confidential at the request of the owners.

Table 6.

Characteristics of entrepreneurial teams—case study.

The entrepreneurial team in Company I consists of a father who was the company founder, and his older son; they plan to invite another son to the collaboration soon. The father invited his son to the entrepreneurial team ten years ago, when he decided to run the business, because he was conscious that the help of a well-educated, young engineer was needed to develop the company. ‘Whom can I trust more than my own family? I knew a lot about the product, I had many chances to observe how it works in practice, so we decided to engage and to devote to our company’. They assessed trust in the team on the highest level and found that the father’s technical knowledge and the son’s managerial competencies, as well as shared values, were the main sources of mutual respect and trust. Both owners admitted that they use each other’s competencies to run the business and to divide managerial roles. The father is responsible for technical aspects, while the son organizes the work and proposes innovative solutions, but they discuss each decision and take it together. The father said: ‘We make decisions usually in online conversations because we travel a lot, but my son’s young head produces all the novel ideas’. The son’s reaction was “I would never question father’s technical opinions, he delivers expert information, plays the role of the technical mentor, suggests solutions and the final decision is obvious for me.” Both partners understand the company’s mission in the same way, and despite saying that they also share company strategy and understanding of venture success, the details they provided differ a little bit. They measure success by earned money, positive clients’ opinions and ecological technology development. While the father appreciates the stability of profits, the size of profits is much more important for the son. The older owner points out the technological excellence of the main product as the most important direction of company development; for the younger one, the most important is the introduction of new products and international expansion. The father does not even think about selling their technical license, while the son takes such a solution into consideration. This does not mean they disagree with each other; both of them are looking for the best way to improve business results and are open to the other partner’s point of view and proposals. They support each other in achieving company goals and feel strongly involved in that process. When the question ‘Do all the members care to achieve the company’s success?’ was asked, participants were both surprised and said, “This is a rhetorical question, isn’t it? Could it be different?”

In Company II, the owners explained that the division of their roles is based on personal competencies, temperaments and preferences. One of them, who is the grandson of the company founder, is responsible for strategy, the other one is responsible for operations. The first one leads the production department, the other one sales. The division is clear for them and their employees, but both of them are and feel responsible for the success of the company and can make all the decisions when the other is absent: “Our employees know, when I am abroad, and a person working in production department wants to renegotiate their terms of employment or to get a rise, he can go to my partner, and he knows what to do, and I will accept the decision”. Both partners assessed the level of trust in each other as on the highest level: 100%. One of the owners is said to be an expert in resolving crisis situations: “He does not know about some processes I control, he forgets immediately even when I tell him. But in crisis situations, he takes a sheet of paper, analyzes, and after ten minutes all the fires are extinguished, he manages it perfectly”. The entrepreneurial team members share the company vision and the strategy to achieve it; they are both involved in running the company. However, their roles were different from the beginning of their cooperation: “He made me think about the business from another perspective: I was a bit ashamed to manage a small business delivering low-quality cakes. He made me think that the confectionery business is a way to give pleasure to the clients and to create the brand we can be proud of”. They also share the same understanding of company success: ‘Our success is that our cakes are unique, hand-crafted and natural’ and both of them are still hungry for more: “We want to be the best bakery in the world”. They support each other on that path, but it does not mean they are unanimous; We often quarrel, we discuss emotionally, we even shout at each other because we have other ideas how to complete the same vision, we have the same priorities. The dispute always is finished with a compromise and a joint decision’. “The most challenging thing in our collaboration is the necessity to give way to the other owner, but we are open to doing so, and we do so”. They are also open to asking the third owner—the mother of one of them—to advise them on some production problems. They agree about her advisory role, and they appreciate her expertise and her right to be a co-owner without taking part in company management. The rules of profit distribution between partners were established and respected even though the distribution is not equal.

The recommended questions to ask to motivate students to analyze the cases are:

- What are the sources of entrepreneurial team success?

- Assess the described entrepreneurial teams using the questionnaire (principles of team collaboration implementation);

- What are the potential challenges the entrepreneurial team can face in the process of company future development? How can they be solved?

- What can inspire your team to strengthen your team collaboration?

7. Conclusions

Our study examined the principles implemented by entrepreneurial teams in the process of their collaboration (ETICP index). We presented the characteristic of entrepreneurial teams and described the rules that are important for team processes within the teams. The factors that distinguish nascent and established teams were discussed to explain our research questions and hypotheses. We also presented the two-factors model for entrepreneurial teams’ effectiveness assessment, including venture performance and team members’ satisfaction.

The main aim of this paper was to examine what collaboration principles are implemented by effective entrepreneurial teams and how they differ in nascent and established teams. A list of nine collaboration principles was formed, and the ETICP scale was designed. To answer the questions about the implementation of those principles in entrepreneurial teams, quantitative research was conducted in a group of 106 Polish entrepreneurs operating in entrepreneurial teams. The first hypothesis was partially confirmed; we found the collaboration principles measured by ETICP index to be implemented by entrepreneurial teams regardless of their experience. Both groups of respondents achieved high results. Contrary to our assumptions, in the case of two particular items of our scale, the obtained scores were even higher in nascent teams.

The other aspect we were interested in was the relationship between the implementation of entrepreneurial team principles and entrepreneurial team performance as well as team members’ satisfaction. The correlation analysis could test the next two hypotheses. The positive relationship between the implementation of entrepreneurial team principles and entrepreneurial team performance perceived by their members was confirmed.

We have confirmed the importance of team collaboration principles in an entrepreneurial context. We also made an attempt to find the relationship between the implementation of collaboration principles in entrepreneurial teams and team member satisfaction at two different stages of entrepreneurial team development. To our knowledge, this issue has not received sufficient attention from scholars to date. The results should be verified in a much larger group of entrepreneurial teams because the number of participants is the most important limitation of our study. The research should also be repeated in groups of entrepreneurial teams’ members in other countries. The locations where the teams operate and the culture of their members could have a bearing on the findings. Our research group was homogeneous in terms of nationality and came from one region of Poland, which limits the universality of the conclusions presented here. Another one is the fact that we have analyzed the results on an individual level: we took into consideration entrepreneurial team members’ assessments and opinions, and we did not perform team level analysis. We leave this task for further research. It would be very interesting to examine the relationship between team congruence regarding the implementation of collaboration principles and companies’ effectiveness through the lens of a shared mental model approach. A very interesting issue to discuss would also be to establish links between two kinds of team performance: financial and non-financial performance with team principle implementation.

Despite the presented limitations, the conducted research findings advance the current understanding of entrepreneurial team collaboration, but, at the same time, allow us to propose some practical ideas to be used in entrepreneurial teams’ operations. The ETICP index can be used as the measure of entrepreneurial teams’ implementation of collaboration principles. The questionnaire we have used to test the ETICP index, called the ETICP scale, can be applied to assess entrepreneurial team collaboration and to propose advisory suggestions referring to the entrepreneurial team and company development. We have not found such a comprehensive tool in other studies, so it can be further developed, validated and widely used.

The other practical implication is related to entrepreneurial education. Three types of recipients of educational activities have been defined: graduate students, nascent entrepreneurial teams and established entrepreneurial teams’ members. The ETICP index and ETICP scale can be used as a reflective learning tool for each of them. The experienced entrepreneurs can analyze their internal relationships, point out the aspects of team collaboration that need to be improved and implement chosen corrective actions to strengthen the team and its business effectiveness. Nascent entrepreneurial teams’ members can use the ETICP items as a template to create their internal rules. Graduate students can reflect their project teams’ behaviors and develop their employability—competencies that are important for their success when accessing a satisfying occupation which benefits a wide range of stakeholders [57].

We have also delivered two case studies that can be discussed during classes concerning entrepreneurial teams, analyzed as the cases of best practices and can be the triggers to implement entrepreneurial team collaboration principles in students’ entrepreneurial activities.

Self-awareness, networking and teamwork are examples of skills that are highly required in the labour market, enhance graduates’ employability [58] and are worth developing even if the student does not become an entrepreneur. The most important practical contribution includes our remarks that refer to team aspects of entrepreneurship, which are often omitted in Polish entrepreneurial education and seem to influence graduates’ and entrepreneurs’ satisfaction and business results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.K.-B., K.S., P.Z., M.T.T.; methodology, B.K.-B., K.S., P.Z., M.T.T.; formal analysis, B.K.-B., K.S., P.Z.; investigation, B.K.-B., K.S., P.Z., M.T.T.; writing—original draft preparation, B.K.-B.; writing—review and editing, K.S., P.Z., M.T.T.; funding acquisition, B.K.-B., K.S., P.Z., M.T.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Science Centre Poland (NCN), grant No. UMO-2017/25/B/HS4/01507.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yoon, H. Exploring the Role of Entrepreneurial Team Characteristics on Entrepreneurial Orientation. Sage Open 2018, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooney, T. What is an Entrepreneurial Team? Int. Small Bus. J. 2005, 23, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, D.A. Towards a theory of entrepreneurial teams. J. Bus. Ventur. 2008, 23, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenkel, M.T.; Garrison, G. Exploring the roles of social capital and team-efficacy in virtual entrepreneurial team performance. Manag. Res. News 2009, 32, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tihula, S.; Huovinen, J.; Fink, M. Entrepreneurial teams vs. managerial teams. Reasons for team formatting in small firms. Manag. Res. News 2009, 32, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolzani, D.; Fini, R.; Napolitano, S.; Toschi, L. Entrepreneurial Teams: An Input-Process-Outcome Framework. Found. Trends Entrep. 2019, 15, 56–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogoda, B. Przedsiębiorczość zespołowa. In Przedsiębiorców; Urząd Miasta Krakowa: Kraków, Poland, 2007; Available online: http://msp.krakow.pl (accessed on 10 May 2019).

- Ben-Hafaïedh, C.; Micozzi, A.; Pattitoni, P. Academic spin-offs’ entrepreneurial teams and performance: A subgroups approach. J. Technol. Transf. 2018, 43, 714–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk-Bryłka, B. Indywidualizm czy zespołowość—W jakich kategoriach myślimy o przedsiębiorczości. Eduk. Ekon. Menedżerów 2016, 3, 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk-Bryłka, B. Attributes of Entrepreneurial Teams as Elements of a Mental Model. Studia Mater. 2016, 2, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensley, M.D. Entrepreneurial Teams as Determinants of New Venture Performance; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kamm, J.B.; Shuman, J.C.; Seeger, J.A.; Nurick, A.J. Entrepreneurial teams in new venture creation: A research agenda. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1990, 14, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glinka, B.; Gudkova, S. Przedsiębiorczość; Wolters Kluwer: Warszawa, Poland, 2011; Available online: https://mfiles.pl/pl/index.php/Przedsi%C4%99biorczo%C5%9B%C4%87 (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Cole, M.L.; Cox, J.D.; Stavros, J.M. SOAR as a Mediator of the Relationship Between Emotional Intelligence and Collaboration Among Professionals Working in Teams: Implications for Entrepreneurial Teams. SAGE Open 2018, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schjoedt, L.; Kraus, S. Entrepreneurial teams: Definition and performance factors. Manag. Res. News 2009, 32, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzenbach, J.R.; Smith, D.K. The Discipline of Teams; Harvard Business Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- De Mol, E.; Khapova, S.N.; Elfring, T. Entrepreneurial Team Cognition: A Review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 232–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preller, R.; Breugst, N.; Patzelt, H. Do We All See the Same Future? Entrepreneurial Team Members’ Visions and Opportunity Development. Front. Entrep. Res. 2015, 35, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyakarnam, S.; Jacobs, R.; Handelberg, J. Exploring the formation of entrepreneurial teams: The key to rapid growth business? J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 1999, 6, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naffakhi-Charfeddine, H. Knowledge Creation in Entrepreneurial Teams. In Handbook of Research on Entrepreneurship and Creativity; Sternberg, R., Krauss, G., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing Inc.: Cheltenham, UK, 2014; pp. 122–144. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Chang, Y.; Chang, Y. The trinity of entrepreneurial team dynamics: Cognition, conflicts and cohesion. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 23, 934–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrone, P.; Grilli, L.; Mrkajic, B. Human capital of entrepreneurial teams in nascent high-tech sectors: A comparison between Cleantech and Internet. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2018, 30, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmar, F.; Davidsson, P. Where do they come from? Prevalence and characteristics of nascent entrepreneurs. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2000, 12, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J. Nascent Entrepreneurs. In The Life Cycle of Entrepreneurial Ventures—International Handbook Series on Entrepreneurship; Parker, S., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lazar, M.; Miron-Spektor, E.; Agarwal, R.; Erez, M.; Goldfarb, B.; Chan, F. Entrepreneurial Team Formation. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2020, 14, 1–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siréna, C.; Fang Heb, V.; Wesemannc, H.; Jonassenb, Z.; Grichnikc, D.; von Kroghb, G. Leader Emergence in Nascent Venture Teams: The Critical Roles of Individual Emotion Regulation and Team Emotions. J. Manag. Stud. 2020, 57, 931–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensley, M.D.; Hmieleski, K.M. A comparative study of new venture top management team composition, dynamics and performance between university-based and independent start-ups. Res. Policy 2005, 34, 1091–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanaelst, I.; Clarysse, B.; Wright, M.; Lockett, A.; Moray, N.; Jegers, R.S. Development in Academic Spinouts: An Examination of Team Heterogeneity. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 249–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisz, N.; Vassolo, R.S.; Cooper, A.C. A Theoretical and Empirical Assessment of the Social Capital of Nascent Entrepreneurial Teams. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2017, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Hafaïedh, C. Entrepreneurial team research and movement. In Research Handbook on Entrepreneurial Teams: Theory and Practice; Ben-Hafaïedh, C., Cooney, T.M., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2017; pp. 11–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hackman, J.R. A Normative Model of Work Team Effectiveness. In Technical Report #2. Research Program on Group Effectiveness; Yale School of Organization and Management: New Haven, CT, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Campion, M.A.; Medsker, G.J.; Higgs, A.C. Relations between work group characteristics and effectiveness: Implications for designing effective work groups. Pers. Psychol. 1993, 46, 823–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, G.B.; Trailer, J.W.; Hill, R.C. Measuring Performance in Entrepreneurship Research. J. Bus. Res. 1996, 23, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer-Hauga, K.; Readb, S.; Brinckmannc, J.; Dewd, N.; Grichnike, N. Entrepreneurial talent and venture performance: A meta-analytic investigation of SMEs. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 1251–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wincent, J.; Örtqvist, D.A. Comprehensive Model of Entrepreneur Role Stress Antecedents and Consequences. J. Bus. Psychol. 2009, 24, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A. The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Rand MC Narlly: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Saari, L.; Judge, T. Employee attitudes and job satisfaction. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2004, 43, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazioglu, S.; Tansel, A. Job satisfaction in Britain: Individual and job related factors. Appl. Econ. 2006, 38, 1163–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, T. Communist legacies, gender and the impact on job satisfaction in Central and Eastern Europe. Eur. J. Ind. Relat. 2008, 14, 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchflower, D.G. Self-employment in OECD countries. Labour Econ. 2000, 7, 471–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, D.E.; Roberts, J.A. Self-employment and job satisfaction: Investigating the role of self-efficacy, depression, and seniority. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2004, 42, 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, D. Self-employment rents: Evidence from job satisfaction scores. Hitotsubashi J. Econ. 2008, 49, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Benz, M.; Frey, B. Being independent is a great thing: Subjective evaluations of self-employment and hierarchy. Economica 2008, 75, 362–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, T. Job satisfaction and self-employment: Autonomy or personality? Small Bus. Econ. 2012, 38, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautonen, T.; Palmroos, J. The impact of a necessity-based start-up on subsequent entrepreneurial satisfaction. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2010, 6, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, B.D.; Zammuto, R.F.; Goodman, E.A.; Hill, K.S. The relationship between hospital unit culture and nurses’ quality of work life/practitioner application. J. Healthc. Manag. 2002, 47, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Collette, J.E. Retention of nursing staff—A team-based approach. Aust. Health Rev. 2004, 28, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, M.; Wirtz, M.A.; Bengel, J.; Göritz, A.S. Relationship of organizational culture, teamwork and job satisfaction in inter professional teams. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.A.; Patterson, M.G.; West, M.A. Job satisfaction and teamwork: The role of supervisor support. J. Organ. Behav. 2001, 22, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breugst, N.; Patzelt, H.; Rathgeber, P. How should we divide the pie? Equity distribution and its impact on entrepreneurial teams. J. Bus. Ventur. 2015, 30, 66–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cressy, R. Why do Most Firms Die Young? Small Bus. Econ. 2006, 26, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, R.M. Reflection: An Essential Tool for Learning. Available online: https://freespiritpublishingblog.com/2017/01/23/reflection-an-essential-tool-for-learning/ (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- Hägg, G.; Kurczewska, A. Towards a Learning Philosophy Based on Experience in Entrepreneurship Education. Entrep. Educ. Pedagog. 2020, 3, 129–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, B.; Wesiak, G.; Pammer-Schindler, V.; Prilla, M.; Müller, L.; Morosini, D.; Mora, S.; Faltin, N.; Cress, U. Computer-supported reflective learning: How apps can foster reflection at work. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2020, 39, 167–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popil, I. Promotion of critical thinking by using case studies as teaching method. Nurse Educ. Today 2011, 31, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonney, K.M. Case Study Teaching Method Improves Student Performance and Perceptions of Learning Gains. J. Microbiol. Biol. Educ. 2015, 16, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, S. Integrating employability into degree programmes using consultancy projects as a form of enterprise. Ind. High. Educ. 2015, 29, 459–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, S. Collaborations in Higher Education with Employers and Their Influence on Gaduate Employability: An Institutional Project. Enhancing Learn. Soc. Sci. 2013, 5, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).