1. Introduction

Academic fraud seems to have spread, or its prevalence has recently received greater awareness, so its prevention is a clear concern of higher education institutions. Indeed, we know that academic fraud affects the credibility of students’ learning assessments, and as a result, the institutional image of educational establishment is also affected, and neither is easy to rehabilitate. This is borne out by the news that recently came to public attention in Portugal in 2018 and 2019, motivated by a study carried out by a team from the University of Coimbra, of the disclosure of the lack of registration of cases of academic fraud by universities, or even of identified cases of academic fraud at the Masters and PhD levels, involving people in public offices.

Research into the phenomenon has made it possible to gain a better understanding of the topic, but higher education establishments’ decisions in this matter frequently ignore scientific knowledge, although they are aware of the fraud problem and are looking to control it. This prompted us to investigate Portuguese students’ perceptions of academic fraud using a qualitative approach to explore it in depth and to identify if any issues need further study. Quantitative approaches have been most frequent in studying academic fraud, which leaves no scope to explore aspects less targeted for investigation. The aim of this investigation is to understand what Portuguese higher education students understand by academic fraud. The analysis of these students’ perceptions is expected to produce useful knowledge for higher education institutions to improve the teaching–learning system regarding the prevention of academic fraud. To contribute theoretically to the systematic knowledge on this subject, this paper focuses on less-explored dimensions in the literature, such as the relationship between the social representations students have of academic fraud and professional ethics and the multidimensional character of the concept of academic fraud. New insights in academic fraud research are also expected by adopting a qualitative methodology, namely by using focus groups, which was used little in the studies we reviewed.

2. Literature Review

Academic fraud can be conceptualised as implying deliberate intent to deceive. For Epstein [

1], it is an intentional effort to deceive, and he considers that a mistake made honestly or a mere difference of opinion, interpretation, or judgment does not constitute academic fraud. Other authors, such as Barnhardt [

2], agree that when academic dishonesty is mentioned, an intention is implied. Referring to plagiarism, others point out that several studies show that cases in which plagiarism is practised with the intention of deception constitute a minority of cases [

3,

4]. The lack of knowledge about academic work and possible different interpretations of academic practices seem to be the main motive for academic fraud. This justifies the claim that academic fraud for some authors should not be regarded as a moral or ethical issue [

5,

6,

7,

8], although other works still focus on the dishonesty of pupils [

9,

10,

11,

12].

Regarding the need to address academic integrity, Gallant [

13] stresses that he has long advocated a pedagogical approach to problems of academic misconduct, rather than a moral approach, but that in 2006/2007, he did not imagine the emergence of an industry associated with academic fraud, reintroducing the question of intentionality, such as that of the ghostwriters White [

14] wrote about.

Although academic fraud is not a recent phenomenon, it can be said that it is a feature of the evolution of education, particularly at the higher education level, and the literature on fraud in higher education has also been growing [

1]. The Bowers study, published in 1964, is recognised as the first to focus on fraud in higher education [

3,

9], and the study by McCabe and Trevino in 1997 is also a milestone [

9]. Currently, however, a search from 1958 to 2020 with the keywords “Academic Fraud” in the subject yields 728 publications, which include academic journals, reports, news, and other journals (search conducted on

www.b-on.pt, a Portuguese Online Knowledge Library, in February 2020). Looking at these results by decade reveals that 79% of publications are from 2011 to 2020, showing that the academy’s research and publishing on the subject has mainly been in the last decade, perhaps because the problem has become more acute over the years despite a lack of awareness of how to contain it, or as a result of the massification of higher education and the growing heterogeneity of students who access it [

4]. However, deeper research shows that the way in which academic fraud is viewed has also evolved over time. In fact, the four publications from 1958 to 1980—the last publication in this interval dates from 1975—focus on issues that, in the light of 2020, seem very far away, one of them portraying a case in which a student sued his school’s board of directors because, having learned to read up to the level of lower education, the school awarded him a higher education diploma. Publications in this period and even those of the following decade seem to deal mainly with fraud practised by educational institutions rather than their students. This observation makes it possible to understand that academic ethics and their opposite, academic fraud, are strongly influenced by the historical–social context in which they are defined, making it difficult to understand what academic fraud is, the forms it takes, the representations that individuals have about academic fraud, its consequences, and its acceptance. The proliferation of terms used to refer to the same phenomenon does not make it easier to study it, either. “Academic fraud,” “academic misconduct,” “academic integrity,” and “research ethics” are just some of the terms used in the literature and in the practices of higher education institutions.

2.1. Representations and Academic Fraud Practices

The forms of academic fraud are varied, and it is not easy to identify which practices are fraudulent. There is also sometimes a lack of consensus on certain practices, which is why some work has been devoted to analysing the social representations that educational actors have about fraud and its practices. Within fraud, we can include practices such as plagiarism, which consists of the appropriation of the work of others; fabrication, which may involve the falsification of information in an activity or also of identity; copying by using unauthorised materials or exchanging information with a colleague; and many others [

15,

16,

17]. Solmon adds obtaining copies of examinations through deceitful means and distributing them to other students [

18]. The facilitation of fraudulent practices is in itself a fraudulent practice and is therefore also referred to in the literature [

16,

17]. However, the types of academic fraud are becoming more and more widespread, taking on nuances that make them difficult to classify [

15]. As an example, Agud mentions a survey conducted by Guillermo Roquet: “inventing content; falsification; fictitious authorship; self-plagiarism or duplication; paid authorship; incorrect citation; missing citation; deliberate plagiarism; unintentional plagiarism; college plagiarism (the copying of fragments from various sites and presenting them in a unified work as one’s own original creation); inappropriate paraphrasing; plagiarism by assignment (delivering the work of others); false citation; plagiarism by coincidence; invented citations; copying a translation; and, the one that affects us the most as teachers, copying and pasting” [

15]. As a consequence, typologies of fraudulent practices are varied; in fact, some authors dedicated themselves to surveying them [

2,

19,

20].

More recently in the literature, there is a preference for using the terms “academic integrity” and “academic misconduct,” which encompass other problematic behaviours such as “plagiarism by staff and students, various forms of cheating, sexual harassment by staff and students in and out of the classroom, misuse of power, exchanging sexual activities for grades, and accepting money or gifts for grades” [

21].

The diversity of nomenclatures and taxonomies will not make it easy for educational agents to identify clearly which fraudulent practices they should avoid and which behaviour they should prioritise, incorporating behaviour that respects academic integrity. The analysis of perceptions of academic fraud has therefore received attention from researchers [

18,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

The lack of knowledge about what is or is not acceptable, i.e., the representations that students have about the phenomenon, is one of the aspects that several authors suggest is at the root of their fraudulent behaviour [

4,

22,

23]. In this regard, especially on the subject of plagiarism, it should not be assumed that students dominate the conventions and rules adopted in scientific work, which are sometimes unknown outside academia [

4], hence the discussion on whether or not academic fraud should be considered in moral terms, i.e., judging the values of those who engage in bad academic practice [

19]. Bloodgood et al. (2010) add that the attitude of students towards academic fraud practices is that of a game they enter in order to obtain high grades [

23]. This can be related to peer pressure to adopt bad behaviour and the fact they may look bad if they do not do so, as everyone does [

22]. Whether it is due to agreeing to enter the fraud game, not falling behind, or for other reasons, not all students see fraud as negative behaviour [

13,

16,

18,

19,

24,

26] or as a crime for which there are no victims [

24]. Moral values weigh little on their propensity to report fraud committed by colleagues, with the distance between the complainant and the fraudster being what most favours reporting [

26].

On the other hand, it cannot be said that academic fraud belongs to any particular area of science, with publications on students or authors in areas such as medicine [

15,

27], pharmacy [

28], management [

29], social sciences [

30], humanities [

6], technological areas [

31], and mathematics [

32]. This does not dismiss the fact that different trends for different areas can be identified, raising the hypothesis that there are different levels of self-efficacy in students from different fields of study [

26]. Additionally, the phenomenon of academic fraud is not confined to a particular country, and the problem can be found in Anglo-Saxon countries such as Canada [

3] and the US [

24]; in European countries such as Bulgaria [

6], Portugal [

4], Spain [

33], Switzerland [

34], and Slovenia [

35]; in Asian countries such as China [

26]; and in other parts of the world such as Saudi Arabia and New Zealand [

5], Australia [

21], Israel [

9], and Russia [

36]. However, there may be particularities and some differences between countries in their greater or lesser preponderance, as shown by some studies [

37], highlighting the influence of cultural factors and the characteristics of education systems.

2.2. Causes and Motives Leading to Academic Fraud

Several factors have been analysed and identified as motivating the occurrence of fraud practices, sometimes depending on the very conception and definition of the concept, as some authors maintain. In this respect, some laboratory studies have been conducted, indicating that the propensity to cheat may depend on the absence of supervision, the expectation of gain, and the risk of being discovered. With this in mind, Cohn and Maréchal (2017) decided to verify whether the behaviour in the laboratory could be transposed to real situations, using the results of a controlled experiment where they recorded the tendency of the participants to cheat, and then compared those records with the teachers’ evaluation of the academic conduct of each student [

34]. They found that the correlation is strong, allowing trust in the results of laboratory studies, regardless of age, gender, nationality, level of education, parents’ education, and cognitive ability. However, despite the relevance that laboratory studies can add, the factors that influence fraudulent practices have been studied mainly using questionnaire surveys [

16,

21,

22,

28,

30,

37,

38].

Attitudes towards fraud seem to be predictors of fraudulent behaviour [

16], and studies focusing on student representations reveal that students tend to rationalise these behaviours, minimising the effects of their wrong actions [

22,

39]. For MacGregor and Stuebs, rationalisation “is the cognitive process of making something seem consistent with (or based on) reason and is used by students to justify aggressive academic behaviours” [

39]. In this sense, Beasley uses the term neutralisation, which he clarifies to be a justification or rationalisation for deviant behaviour, making it more acceptable, even if the perpetrator recognises that the action is wrong [

22]. Hence, in the context of academic fraud, rationalisations can be considered students’ justifications of their academic misbehaviours in order to achieve greater congruence with their personal values and with the ones that are accepted in society in general.

MacGregor and Stuebs considered four types of rationalisation that students tend to present to justify fraudulent behaviour: (a) the behaviour of peers, (b) ignorance due to the ambiguity of instructions, (c) unrealistic expectations of the instructor, and (d) minimising fraud as insignificant and unimportant [

39]. Some of these rationalisations are recurrent in the literature, such as stress and the relationship with the teacher, but also include insufficient time to study, pressure to get good grades, ineffective prevention, difficult material, resentment towards the system that led them to it [

16], fear of failure, and laziness [

28]. In the Beasley study, the causes pointed out were: (a) ignorance of the consequences, (b) ignorance of the rules, and (c) neutralisation, i.e., rationalisation of their behaviour [

22]. According to the author, the neutralisation techniques used by the students focus on the teachers’: (i) condemning the condemned and changing the guilt, i.e., their ignorance is the fault of the teachers; (ii) the teachers’ negligence, thinking that they do not care; (iii) incomprehension by the teachers; (iv) the teachers not giving good lessons; and (v) condemnation of the system. In a more recent paper, reviewing the literature and using the work of Sykes & Matza published in 1957, the authors list the following neutralisation techniques: (a) denial of responsibility for their actions, alleging overwork or ignorance of the rules of citation, for example; (b) denial that the fraud has consequences, arguing that it is not harming anyone; (c) denial of the victim, for example, not seeing the academic fraud as negative or blaming the victim, for example blaming the teacher for not being diligent in vigilance; and (d) condemnation of those convicted, diverting attention to others, often the teacher, for not having made material available, giving too much work, not helping, or not being understanding [

7].

Other factors that do not constitute rationalisations include gender, and there are studies that reveal a greater propensity of males to commit fraud, either because they have greater acceptance of these practices [

16] or because females tend to avoid risk [

26]. Psychological factors such as perceived behavioural control and moral obligation [

16], narcissistic traits sometimes attributed to millennials [

30], Machiavellian traits [

23], or selfishness and utilitarianism [

38] reveal that the acceptance of fraudulent behaviour or the propensity to commit fraudulent practices is relevant.

But while some researchers find reasons attributable to students, others point to factors that are extrinsic to them. Indeed, as Barnhardt points out, academic fraud is a multidimensional construct [

2]. Situational factors such as the opportunity to commit fraud are some of the factors that can increase the propensity to adopt fraudulent behaviour [

18], which includes easy access to technologies such as the Internet, smartphones, smartwatches, and smart glasses, that create that opportunity [

10]. This is particularly relevant, as it points out that fraudulent acts can be more impulsive and constitute behaviour that is not entirely rational. It is also curious that the technology used in the game of not learning has the prefix “smart,” reifying in students the notion that by committing fraud they are being “smart.”

2.3. Measures to Combat Academic Fraud

The large numbers of students who admit to engaging in fraudulent acts or academic misconduct oblige teaching organisations to take measures to contain or avoid such practices. The students themselves, when questioned about the causes and motives for these practices, criticise the system and express the perception that teaching organisations should take action.

According to Gallant [

8], quoting the works of Paine in 1994, and Whitley and Keith-Spiegel in 2002, schools tend to assume two strategies: (a) disciplinary, to ensure compliance with the rules, punishing those who break them and where the tone is often legalistic and confrontational [

40], and (b) integrity, which acts on the character of students by seeking to internalise institutional rules as a pedagogical-formative strategy without dispensing with the first strategy’s clear procedures that must be defined and followed [

8]. In fact, as stated by Epstein, small acts of fraud can lead to disastrous consequences when there are only single, lenient procedures [

1]. According to this author, the existence of formal procedures also has the function of avoiding false accusations of fraud in academia. Gallant [

40], in turn, reiterates that the integrity strategy does not mean giving up discipline but rather using it as a tool and not as central policy.

However, it is increasingly argued that educational organisations should also take on the integrity strategy [

8,

18,

40,

41,

42,

43], and there is research that highlights the relationship between teaching–learning methods and the lesser or greater propensity for students to adopt bad academic behaviour. It can also be argued that this position reflects the point of view of teachers and institutions and not so much that of learners, who value disciplinary strategy more [

44]. In this study, the authors found that the disciplinary strategy was most highly valued by students, who advocated measures such as heavier sanctions, parental notification, anonymous reports, and implementing a systematic policy. They also found that the measures considered less effective by the students were the existence of a code of honour, no strategies, compulsory ethics courses, and letting the teachers decide the sanctions. Still, regarding students’ views about the measures to be adopted, it can be said that they have a more critical view of certain forms of fraud, advocating for heavier sanctions for these [

2]. On the other hand, institutional practices vary widely, as demonstrated by the study on academic integrity policies, particularly for combating plagiarism, cited by Hodgkinson et al., where universities from 27 countries participated and where it is also pointed out that policies and measures tend not to be implemented systematically and consistently [

10]. In fact, a still-preliminary report of the study acknowledged that among the main barriers in the fight against plagiarism were entrenched ideas adopted by the governments themselves and the access to new and now-widespread technologies [

45] and thus also the difficulty of educational organisations to adopt policies and measures to combat it. Some research points out that educational organisations tend to adopt internal measures, and that unlike financial fraud, they tend not to involve the judicial system [

17]. A number of preventive techniques have been surveyed, including the adoption of teaching, monitoring, and evaluation methods that have the effect of reducing the occurrence of fraud and that can be useful for universities to rethink their practices [

10].

The adoption of teaching–learning methodologies that develop other competencies in the students besides the memorisation of contents allows for creating a favourable learning environment. This is intended to remove the focus on performance, where assessments are superficial, easy, or maladjusted to learning objectives and favour learning that is also superficial and motivated only by grades [

41]. Presenting varied literature on the subject, Gallant takes up her 2008 thesis and maintains that environments that favour the learning of varied competences naturally reduce the propensity to commit academic fraud by developing in students the motivation to learn and the capacity to self-evaluate their knowledge, what they need, and how they can acquire it [

41]. The adoption of assessments that make sense to students also allows them to acquire an awareness of what they have gained from learning.

2.4. From Academic Fraud to Professional Ethics

The assumption that conduct, both ethical and unethical, in a school context can be transposed into the professional context or signal future unethical work conduct is sometimes referred to in the literature. However, specific research on this dimension of analysis is neither abundant nor recent. While not empirical in nature, Agud systematises the consequences that academic fraud practices may have on medical research and practice, affecting the fairness of future performance evaluations, and states that in terms of research, the publication of invented results and refusal to publish honest research can have serious consequences [

15]. Honing et al. has reflected on scientific misconduct in the area of management, also with regard to publications and scientific work undertaken [

46]. Other authors also refer to fraud committed in scientific publications [

40,

47,

48], some addressing in particular industries dedicated to providing academic fraud services, such as contract cheating [

49] or ghostwriters [

13,

14]. On the relationship between students’ bad academic practices and their future professional ethics, some references may provide points for reflection. Although not the focus of their research, Alleyne and Phillips refer to some studies that support the existence of a relationship between the adoption of dishonest behaviour in academia and the subsequent manifestation of dishonest behaviour in a professional context [

16]. Burrus et al. also found studies that make it possible to establish this relationship [

12], while Bloodgood et al. raises the hypothesis that more competitive professional environments are more likely to trigger less ethical behaviours [

23]. Studies by Cohn and Maréchal also make it clear that behaviours in controlled contexts, even laboratory ones, can be predictive of behaviours assumed in other contexts [

34]. However, the occurrence of academic fraud does not always involve intentionality [

2], which makes it possible to suggest further research into this under-exploited dimension. However, it is also worth recalling the work, for example, by Teixeira, highlighting the relationship between academic fraud and corruption rates [

50].

3. Materials and Methods

In order to analyse students’ perceptions of academic fraud, focus groups were used among undergraduate students from a school at the University of Lisbon, and conversation was stimulated among them, as suggested by Colella-Sandercock [

3], to reveal their attitudes and involvement in practices such as plagiarism and other forms of academic misconduct.

Four focus groups were organised on the following themes: (1) representations and practices of academic fraud, (2) causes and motives leading to academic fraud, (3) measures to combat academic fraud, and (4) from academic fraud to professional ethics.

The researchers disseminated the implementation of the focus groups. The 34 students who volunteered to participate were distributed among the four focus groups as they arrived, targeting each group with a similar number of participants and heterogeneity in terms of gender and courses. Thus, each of the groups was composed of about 8 or 9 participants. A total of 22 girls and 12 boys from undergraduate studies in human resource management, sociology, and communication sciences, mostly in the second and third grades, participated.

The activity was carried out in four phases, each lasting 20 min, so that each participant would participate in the four focus groups and discuss all the planned themes. In all the phases, each focus group had two moderators, both teachers—one with the function of stimulating and moderating participation, the other with the function of recording in writing the main ideas of the interventions. Having previously obtained the authorisation of all the participants, the activity was recorded for subsequent transcription and analysis of the thematic content.

Care was taken in the preparation of the activity, which involved training the moderators to understand the objective of the work, the script, and the reception procedures in each focus group. Moreover, no information was given to students in the previous months and during the implementation of the activity on academic fraud in order to avoid bias in the students’ social representations. The moderators were careful not to express opinions, taking care to remain neutral and not to display verbal or non-verbal language that could reveal their position concerning what was verbalised by the participants.

A semi-structured script was prepared for each focus group with 5 to 7 questions. The following is an example of questions for each topic: (1) representations and practices of academic fraud (e.g., “What is academic fraud to you?”), (2) causes and motives leading to academic fraud (e.g., “What drives people to commit academic fraud?”), (3) measures to combat academic fraud (e.g., “What do you think should be done to prevent academic fraud?”), and (4) from academic fraud to professional ethics (e.g., “Is there a relationship between academic fraud practices and unethical professional practices?”).

The study followed ethical principles in accordance with the American Psychological Association (2017) [

51] with respect to human research (objective information, risks and benefits of the study, protection of personal data and guarantees of confidentiality, gratuitousness, and the possibility of abandoning the study at any of its stages).

The data collected were subject to content analysis [

52]. A category system for coding the data was developed based on a bottom-up technique (i.e., emerging coding), with the theme as the unit of analysis; the sections with participants’ replies that referred to the same theme were grouped together.

The content analysis was carried out with the help of Max-Qda software. To ensure the quality of the category system, two independent researchers coded 10% of the collected (randomly selected) transcriptions. The value of the interjudge agreement indicated a very appropriate level of reliability for the category system (k of Cohen for interjudge agreement: 90%).

4. Results

This process made it possible to identify 62 sub-categories whose designation reflects the content of the themes. These categories were grouped into 24 broad categories, which were in turn grouped into the four focus group themes. A total of 448 codifications were made.

4.1. Representations and Academic Fraud Practices

In terms of representations and practices of academic fraud, the focus groups made it possible to extract 14 subcategories organised into four main categories: forms of academic fraud (five subcategories);, unfamiliarity with academic fraud, forms of acquisition (two subcategories), and attitude towards the practice (seven subcategories).

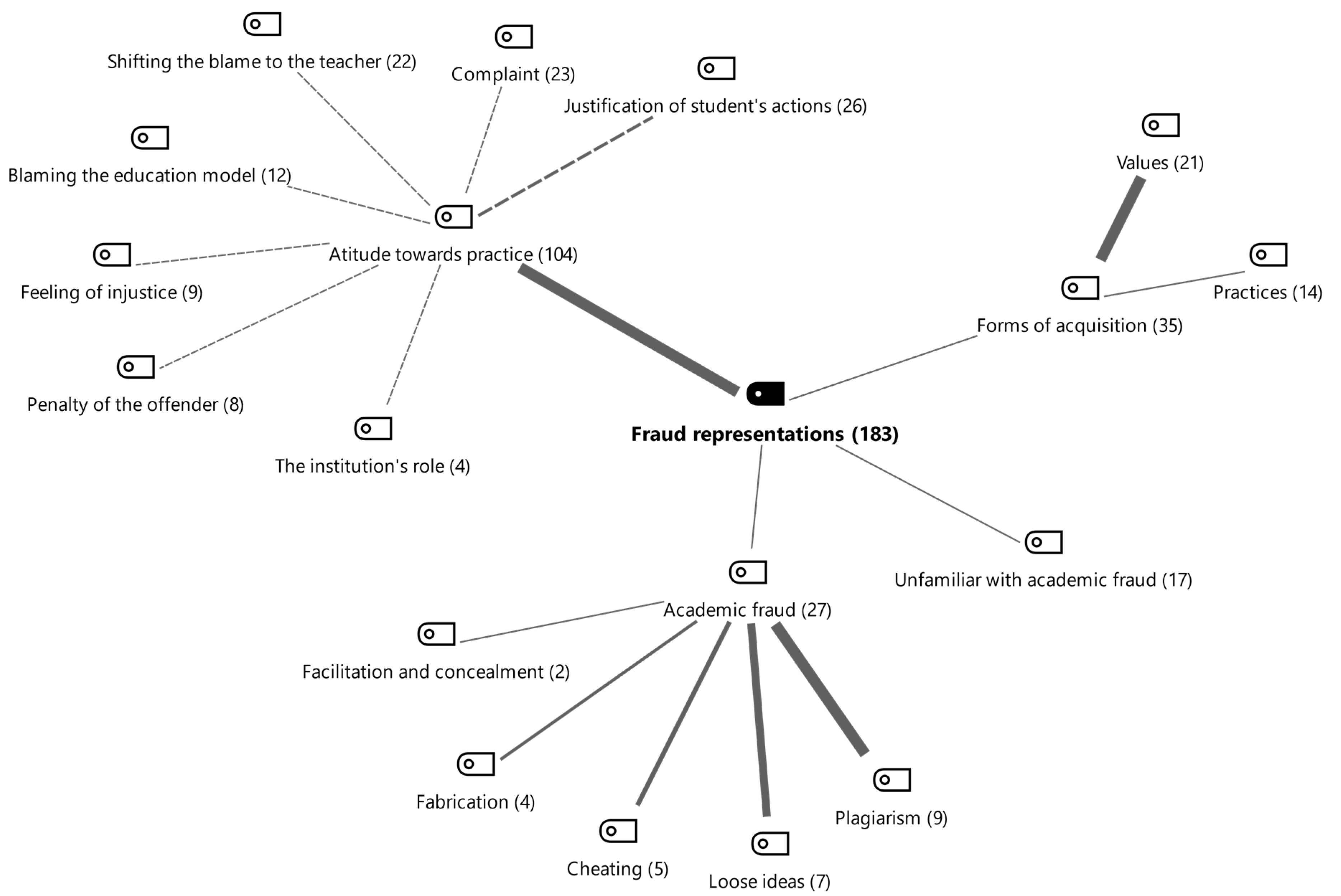

When the results were analysed in terms of the four thematic groups, representations of fraud was one of the most discussed (with 183 references), as presented in

Figure 1. The focus of the discussions was mainly on attitude towards the practice of academic fraud (104 references), showing evidence of students being keener to express their personal views on academic fraud than their views of what they understood academic fraud to be. Several attitudes were neutralisations such as the justification of students’ actions (26 references), arguing, for example, “Some people have a very good memory and can write exactly the same words as there are in the handbooks. I see it can be considered as plagiarism, in an involuntary way,” or claiming, “Signing for someone else is not that serious.” Another neutralisation emerged as shifting the blame to the teacher (22 references), with participants stating, “It depends a lot on the teacher, because there are teachers who say they want a standard answer and others say they want us to process the information and give a critical opinion,” that, “Teachers don’t do anything, it seems as if they don’t want to know,” or even that, “When the teacher does not captivate or motivate students, it becomes much more difficult for the student to understand the subject. Then, in despair, he turns to cheating.” Neutralisation through condemning the system (12 references) was also noticed among students’ attitudes. The willingness of the students to report unethical behaviour was also much debated (23 references), although they tend to reject the idea of reporting: “It is a very cultural problem. If you ask that question in Portugal, most of the students will answer no, but in other countries students would say yes.”

In terms of forms of academic fraud (27 references), participants most frequently identified it as plagiarism (nine references), cheating (five references), and fabrication (four references), or stated loose ideas (seven references) on the topic. Regarding the ways of acquiring these practices (35 references), students tended to admit that academic fraud is a practice they have done since primary school and are therefore used to it, considering that it can affect their moral values when they see that practitioners succeed with the practice. We highlighted the views expressed in the category of unfamiliarity with academic fraud (17 references), which refers to the manifestation of the lack of information, which manifests itself in the lack of knowledge of the rules of scientific writing as well as the forms and characteristics relating to academic fraud on the part of the participating students.

4.2. Causes and Motives Leading to Academic Fraud

Regarding the causes and motives leading to academic fraud, the content analysis made it possible to identify 20 subcategories that were organised into six categories: practices in high school (two subcategories), personal attitude of the student (five subcategories), evaluation (three subcategories), teaching (five subcategories), social pressure (three subcategories), and ignorance (two subcategories).

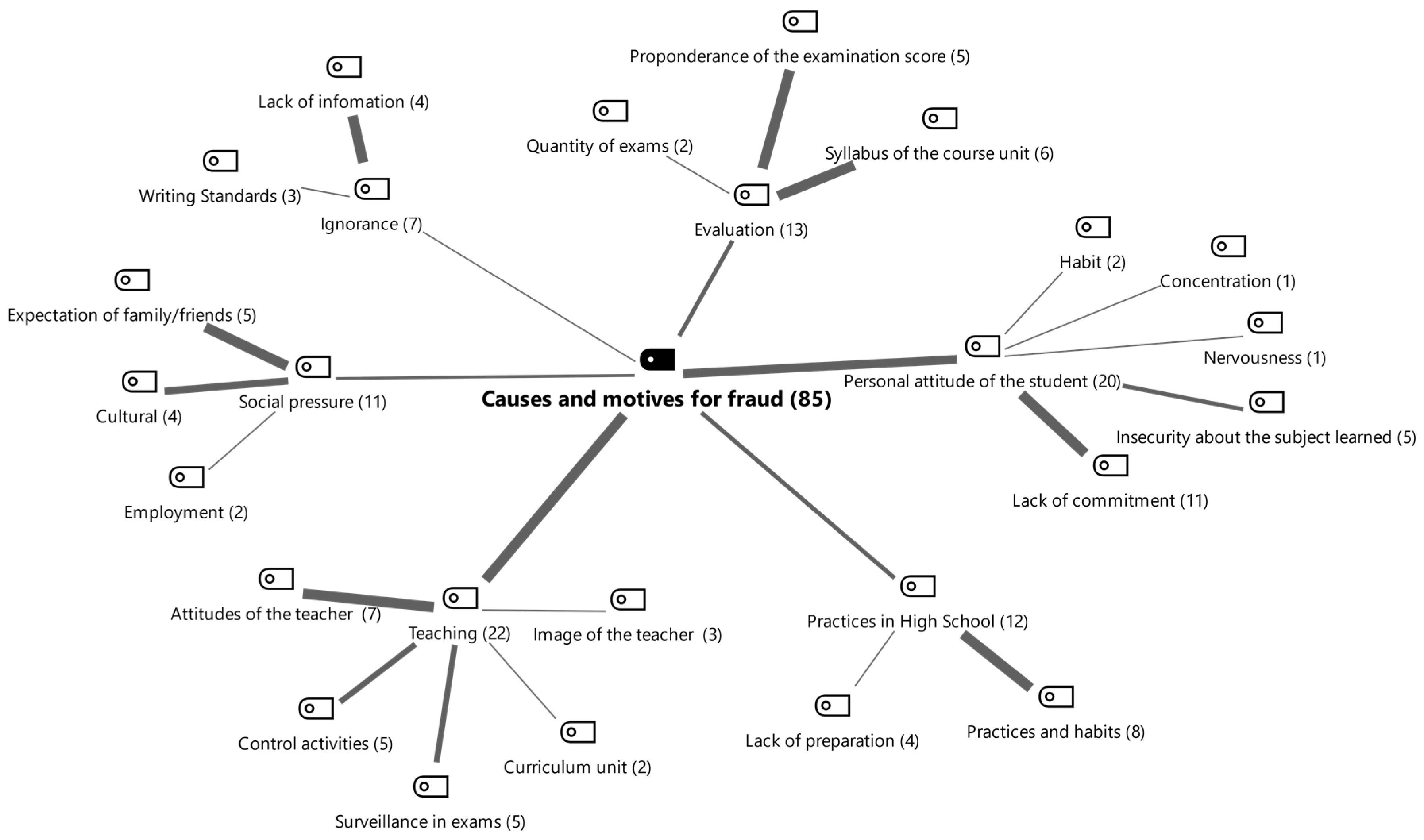

The content analysis of the causes and motives leading to academic fraud (85 references), the synthesis of which can be seen in

Figure 2, revealed that the education system is considered the main cause of academic fraud, including teaching (22 references), evaluation (13 references), and practices in high school (12 references). The personal attitude of the student (20 references) was not expressive when compared with the set of those three subcategories.

Regarding teaching, the students complained about the teacher’s attitudes (seven references), considering that “Some teachers sometimes cause some instability, saying ‘It will be difficult,’” or “There are teachers who want us to repeat word for word what they teach in class.” Surveillance in exams (five references) was another reason, with students complaining about how teachers neglect that task—as one student pointed out, “Being at the computer, not paying attention to the room,” and, “There are teachers who have seen it [students cheating] and they do nothing.” Students also mentioned control activities (five references) where they referred to the relation with the teacher (that the teacher can be too close to some students, or in contrast that the teacher is too distant) but also their negligence in monitoring students’ work.

Evaluation (13 references) as a cause of academic fraud in student’s views derived from the syllabus of the course unit (six references) because of the extension and complexity of the subjects for evaluation; from the preponderance of the examination score (six references), defending continuous assessment; and from the number of examinations (two references): “If I have six exams I’m more likely to cheat.”

Students also perceived that practices in high school were one of the causes of their unethical behaviour, because of the practices and habits they learned in that context (eight references): “In high school, we copy/paste an essay on the internet”; “I think cheating and plagiarism are something that comes from high school”; “High school essays are not very rigorous—we can copy and teachers do not give a damn.” However, students also argued that high school does not prepare them for the demands of higher education, neutralising their responsibilities through the lack of preparation (four references).

Regarding the personal attitude of the student, a lack of commitment (11 references) was the main reason. Participants recognised that students engage in unethical behaviours due to laziness and because they do not want to study, among other similar reasons. Finally, it should also be noted that ignorance appeared only as a marginal reason.

4.3. Measures to Prevent Academic Fraud

When the academic fraud prevention measures were analysed, nine subcategories emerged, which were organised into eight categories: sanctions (five subcategories), software, information, personal attitude of the student, teaching, evaluation methods, training (two subcategories), and role of the institution (four subcategories).

The content analysis of measures to prevent academic fraud (85 references), as shown in

Figure 3, shows that most participants spoke about sanctions (24 references), the role of the institution (18 references), and evaluation methods (15 references). Reclassifying all the categories and the subcategories showed two major strategies: an integrity strategy and a disciplinary strategy.

An integrity strategy emerged from grouping together the categories and subcategories related to a pedagogical focus, such as the role of the institution/providing information, both subcategories of training, evaluation methods, teaching, personal attitude of the student, information, and software. A disciplinary strategy emerged from grouping the categories and subcategories with a disciplinary focus: the role of the institution/production of regulations, the role of the institution/sanctions, the role of the institution/implementation of regulations, and all sanction subcategories. Participants seemed to be more favourable of an integrity strategy (48 references) than a disciplinary strategy (37 references). As an integrative strategy, participants referred to mostly evaluation methods (15 references), such as reducing the syllabus of the course units or sustaining the effect of continuous assessment and training (nine references), either in high school or higher education. The sanctions participants most defended were annulment of proof/work (10 references).

4.4. From Academic Fraud to Professional Ethics

When the considerations concerning professional ethics were analysed, 14 subcategories emerged, which were organised into six categories: personal attitude of the student (three subcategories), the labour market (two subcategories), values (four subcategories), personal attitude of the teacher (three subcategories), training (two subcategories), and the role of the institution.

Regarding how participants perceive the relation of academic fraud to professional ethics (95 references), as presented in

Figure 4, the category of the personal attitude of the student (31 references) emerges, mainly due to social perception (20 references), which may condition the student’s attitude towards the practice of academic fraud. Some of the participants’ statements reflected the kind of pressures they feel: “The one who cheats is the cool one”; “Being with someone else may not affect the way I think, but it can make me act differently, for better or for worse”; “The message that is given to us is a good student is the one with good grades.”

The labour market (29 references) was the second major topic that participants discussed, and their views were not consensual. Most frequently, they expressed that academic fraud is not related to occupational ethics (18 references): “I do not think that a student who commits academic fraud is bound to commit fraud in his professional future (…) maturity and commitment are different in this context”; “The best students are not always the best professionals.” Others, however, do see academic fraud as being related to occupational ethics (11 references) saying, “If a student does it [academic fraud] on a regular basis, he will easily be able to sabotage the work of his colleagues or take advantage of it in the professional environment” or, “The best student is probably the one who studies and learns working methods.”

Another major topic discussed by the participants was values (20 references). Some participants viewed the debate as a question of ethics (nine references), for example, defending that “Through academic ethics what we learn ends up being a basis for being in the job market, in the professional context in a generic way”; but other participants understood it instead as another notion of ethics (eight references), stating, “I think that a person who does cheat is much more capable than a person who just memorises. Now, as a team leader I want a person who gives me results,” or even that it was not a question of ethics (one reference). Another participant did not believe it was a question of ethics, stating, “Fraud does not inevitably come from the lack of values, but from need. Necessity is the reason why a person/someone would not/does not respect values.”

5. Discussion

The perceptions of the students who participated in this investigation are guided by diversity; they focus on aspects already mentioned in other investigations but allow us to account for its complexity, offering nuances that are still little explored. In effect, the analysis of these students’ opinions allows us to resume the discussion of whether academic fraud should be stated in moral terms [

19,

23]. In fact, we found different notions of morality between students. For some, fraudulent practices are clearly condemnable and compromise science itself, while for others, they may be perfectly acceptable, meeting values that, in their opinion, are valued in the labour market. Furthermore, as these students expressed, and as other studies have identified [

53], fraudulent practices are crystallised, resulting from consensual habits throughout secondary school. Thus, the promotion of a culture of academic integrity must begin before higher education, promoting more and better information throughout the school path about good academic practices. This could be done, for example, by using the participation of higher education institutions; discouraging facilitating practices that do not encourage reading, such as studying through slides; and encouraging the completion of work using reliable sources. In higher education, actions can also be organised to clarify which values and practices should prevail and which are rewarded, where students openly discuss the consequences of adopting fraudulent practices. Potential employers and recruiters may also be called upon to participate, helping to change students’ perceptions of the most valued values in the labour market. It should be noted that in this respect, the perceptions of students are sometimes contradictory. Some consider that the end justifies the means—achieving results is what matters most—but on the other hand, they separate academic ethics from professional ethics, i.e., they may believe that an individual who commits academic fraud will not necessarily commit fraud in a professional context, which is not supported by research [

16], although this dimension has been less explored. According to these students, individuals have a blank slate when they move from one context to another and do not negatively judge colleagues who have achieved academic success through fraudulent behaviour. They tend to devalue fraudulent behaviour, a trend also identified in several studies [

13,

16,

18,

19,

22,

24,

26,

39]. Others make it clear that they would not trust some colleagues in a professional environment if they knew of their academic practices. Bad practices seem to be worthwhile, in a system where reporting is maligned by students and teachers [

4,

53,

54] and where institutions seem not to have effective mechanisms to combat them. Identifying and giving a voice to honest students could contribute to diminishing the sense of impunity that exists among students with bad practices. On the other hand, although reporting could have a deterrent effect, it could endow the system with other problems, and it is difficult to distinguish legitimate reporting from reporting motivated by envy and the desire to harm colleagues regardless of their practices. Further discussion on its use could help to clarify its usefulness and the doubts it raises.

Alongside devaluation, students also tend to rationalise fraudulent behaviour by focusing on the role of the teacher or lecturer, as also highlighted in other research [

7,

16,

22]. Both in the focus group that focused on the representations and practices of academic fraud and in the one where the causes and motives leading to academic fraud were discussed, this was the most prominent aspect (e.g., teachers were distant, suspicious, not understanding, and did not effectively monitor, among others). The study by Cohn and Maréchal, however, shows that some of the teachers’ behaviours, such as the lack of vigilance, can in fact affect the students’ propensity to commit fraud [

34]. As for the type of teacher–student relationship, it is difficult to understand which characteristics may diminish the propensity for academic fraud. It is suggested that this is a topic on which further study is needed.

Ignorance is also widely referred to as a form of neutralisation or rationalisation of unethical behaviour [

4,

22,

23]. In this research, ignorance was not the subject most discussed among students in any of the focus groups, although they commented that they were unaware of some forms of fraud, such as self-plagiarism, and the applicable sanctions. However, other forms—such as copying, forgery of signatures, and some forms of plagiarism—are known and used intentionally by students. Hence, the lack of commitment among students has also been pointed out as one of the main causes of academic fraud. Although laziness is mentioned in some of the studies consulted, the prominence of an aspect intrinsic to the student him- or herself is infrequent and highlights the present research. The use of focus groups, which facilitate the exchange of opinions between students without constraints, and the students’ voluntary participation in them, may justify a greater propensity to admit intrinsic motives arising from students. It is not usual for students to justify their school failure in this way. In fact, in some studies on the subject, students, especially males, tend to attribute their failures to external factors such as teachers and tests, among others [

55]. The sincerity of the participants obtained using this methodology makes it possible to suggest its use in future investigations focusing on this phenomenon.

Students’ comments on pedagogical and evaluation methods, highlighted in the discussions around the representations and practices of academic fraud, the causes and motives for academic fraud, and the measures to prevent academic fraud, should not be forgotten. There is also some resentment among students on these issues. In fact, repressive measures based mainly on the application of sanctions to students caught committing fraud do not seem to have decreased the prevalence of these practices. According to students’ perceptions, which call on institutions to define and apply regulations, students feel wronged when teachers close their eyes and colleagues who commit fraud go unpunished, so the application of sanctions cannot be neglected in order to avoid feelings of injustice and impunity. This is also how the values of academic integrity, so important in contexts where scientific knowledge is produced and disseminated, are affirmed. However, more educational and less repressive environments may promote less resentment on the part of students and tend to reduce the propensity to comment on academic fraud. This was an idea advocated by students who participated in focus groups and is also suggested in several studies [

8,

18,

40,

41,

42,

43].

6. Conclusions

This paper’s main goal was to analyse Portuguese students’ perceptions of academic fraud following a qualitative approach, and to that purpose, four focus groups were organised on the following themes: (1) representations and practices of academic fraud, (2) causes and motives leading to academic fraud, (3) measures to combat academic fraud, and (4) from academic fraud to professional ethics.

In the focus group on representations and practices of academic fraud, students were more eager to express how they felt about academic fraud and less keen to talk about what they thought academic fraud was. When the focus group was redirected to the students’ representations, references to plagiarism stood out, but students tended to have general notions of what academic fraud is. This focus group allowed us to understand that academic practices need to be addressed in more pervasive ways for students who do not realise which academic practices they are supposed to follow and internalise. How establishments are teaching these practices must be discussed and deserves further study, because it seems to be ineffective. Students’ attitudes regarding academic fraud reinforce this statement because they mostly are rationalisations of students’ poor habits. These results may reveal that academic fraud practices may be internalised, which makes them much more difficult to eradicate when students are already in higher education. One suggestion is to initiate academic fraud combat when students move on to the second cycle of the Portuguese education system (corresponding to the fifth year of school), which is much more complex and demanding, with different disciplines and teachers, and could be an early stage for support and information on academic integrity. This could be a way to prevent fraud and stimulate academic integrity.

In the focus group on causes and motives leading to academic fraud, students tended to rationalise behaviour by blaming the teacher and the evaluation; therefore, their attitudes towards the education system are clearly not positive. This did not prevent them from assuming some of the blame themselves, namely admitting a lack of commitment as one of the causes. However, they also imputed charges to practices they acquired at secondary school, a more endemic cause related to educational structural deficiencies. Additionally, students did not stress ignorance as being one of the main causes, as shown by some studies, which contrasts with their diffuse representations of academic fraud. A possible explanation is that these students commit academic fraud because they do not know what academic fraud is, even if they do not rationalise their behaviour through their ignorance on the subject.

The results of the focus group on measures to prevent academic fraud reveal that these students prefer an integrity strategy (48) over a disciplinary strategy (37), contrasting with studies that have highlighted that the disciplinary strategy tends to be more highly valued by students. The qualitative approach of this research may provide one possible explanation because students’ opinions were not induced by previous answers in a survey and instead emerged during the discussions. It is therefore possible that students’ perceptions on measures to combat academic fraud are not significantly different from those of the teachers and institution administrators, contributing to a better understanding of students’ perceptions on academic fraud.

This article offers a better understanding of how students understand the relationship between academic fraud and professional ethics, which is rarely considered in research on academic fraud. In this regard, the students’ opinions were not consensual and reported complex and diverse senses of reasoning. Some had a clear sense that academic fraud undermines science and has a relation with future professional profiles. Others did not perceive the existence of a relation between academic fraud and professional integrity, believing that people may act in a completely different way in a different context. Others also saw academic fraud practices as possible valuable traits once in a future professional context, arguing these practices can be seen as possessing problem-solving skills, for example. This diversity of perceptions shows a dissimilar sense of ethics among the student population that must be addressed, questioned, and considered when aiming to combat academic fraud.

Investigating academic fraud in a qualitative approach was effective in uncovering controversies, paradoxes, and meanings that are not available through a hypothetical–deductive approach, but empirical generalisations were not possible nor intended. Therefore, a limitation of this research is not providing general conclusions to the entire population. Another limitation is the sample composition, which was restricted to a single higher education institution and to social sciences students. A more diversified theoretical sampling, including graduate-level students from different institutions and scientific areas, could provide differentiated representations and introduce new perspectives.

The use of these four focus groups seemed to be useful in the study of perceptions on academic fraud, and they could be used to compare to teachers and employers’ perceptions. Further studies can also explore the impact of news about and cases of academic fraud in the confidence in higher education institutions. Future research could also focus on other college-level students’, such as masters and PhD students’, perceptions, with more focus on academic fraud types that are more significant for research activity, such as plagiarism, inventing content, falsification, and many other forms of fraud that have become more salient.

integrity strategy and

integrity strategy and  disciplinary strategy.

disciplinary strategy.

integrity strategy and

integrity strategy and  disciplinary strategy.

disciplinary strategy.