Abstract

The changes observed in the school context demand new practices and impose new challenges to the operational assistants that, due to their relevant role in the educational environment, must be prepared and endowed with knowledge and skills to conduct their profession in a fully useful way. This is only possible through the promotion of their training and capacitation in a real work context. Through the European project entitled “Innovative Plans to Combat School Failure” which was implemented in Portugal, we assess the impacts of a training-capacitation action directed to operational assistants and explore the dynamics and influences underlying the learning process put in practice in the schools of the county of Sintra. This assessment conducted by a higher education institution (Iscte-University Institute of Lisbon) mobilized a mixed methodology-survey and focus groups with operational assistants and interviews conducted to school directors. We verified that a training activity conducted in the real working context potentiates the performance of these professionals, namely in terms of autonomy and adaptation to different contexts and duties, conflict management and cooperation, whose effects reflected on the organizational dynamics of the school institutions of the county of Sintra.

1. Introduction

Thinking about education as a process of knowledge acquisition and construction requires one to acknowledge that the learning process in a school does not simply occur in conventional teaching spaces such as the classroom but also outside of it. Thus, we should pay closer attention to all professionals that integrate the school organizations and act to potentialize the learning process of students as it is the case of operational assistants.

In the school environment, the operational assistants’ functional contents are multifaceted, meaning that it includes the equipment’s maintenance and the escorting and surveillance of the students. Aside from that, they are called to participate actively, flexibly and in an informed way in the school community by interacting regularly with the families and the academic and social environment that is involved. They are also the first contact that exists between the school and the environment itself, namely with the families as they are the ones who wait for them in the entrance gates. From the current Portuguese legislation (Law No. 184/2004) that defines the main duties of these professionals, we highlight the following ones: “(a) to participate with teachers in monitoring children and young people during the school’s operating period, in order to ensure a good educational environment; (b) to clean, to preserve and ensure the good use of the facilities, the didactic and computer equipment’s and other materials necessary for the development of the educational process; (c) to carry out tasks regarding customer service, escort the school users and control entries and exits from the school; (d) to provide support and assistance in first aid situations and, if necessary, accompany the child or student to health care units”.

Knowing that the role performed by these professionals in schools is becoming more relevant, their training and integration is imperative. On the one hand, such training is to grant the improvement of their performance and on the other hand to achieve an educational quality that respects the ongoing functioning of teaching organizations. In this sense, O’Connor et al. [1] point out that the agents in the work context should be prepared to better perform their tasks; however, this preparation must come from the development of specific and necessary skills to aim a change on the general behaviors and practices. That implies that organizations must be able to identify the problems/menaces and acknowledge that training and capacitating their agents continually is essential to answer the challenges that are presented to them. It also foresees that workers should be motivated or should demonstrate a predisposition to learn permanently and to adapt/change their behavior [2]. Aside from that, both the motivation to and the recognition of the training action should be considered as it is not always restricted to the training process. This means that the main wish of the trainees is to acquire knowledge that can effectively be put in practice.

Therefore, it is related to develop skills and to transmit knowledge that will prepare the operational assistants to become more effective throughout their functions (from the variety of duties to be performed by operational assistants, we highlight their participation and cooperation in supporting activities and socio-educational activities involving students and their families), preparing them for a variety of possible tasks they should perform, boosting them to assume more broad and demanding tasks in the future [2,3,4], thus promoting a school environment that provides improved learning and eases the process.

In this sense, we take as an example of analysis an innovative educational project of municipality focus named “The School Grows with Us”, financed by the European Union and executed by the municipality of Sintra and developed by the Professors Association of Sintra. The reason for choosing this project is related to the fact that operational assistants are part of a group that is not always considered as an important element for change in the school dynamic. This project aimed exclusively to train and capacitate the operational assistants of the county of Sintra, which is the second most populated in Portugal, whose school network integrates 123 teaching institutes and 58,361 students (school year 2019/2020). Knowing that the effectiveness of the training activity is better succeeded when the intervention is evaluated, a group of external researchers from Iscte-University Institute of Lisbon, one of the most consecrated institutions in Portugal in the evaluation of educational policies, were called to implement and assess the project.

This said, the objective of this article is to put in evidence, opening with an evaluation supported by theory, what were the impacts of the training and capacitation action of the operational assistants and in which extent change was achieved in the sense of improving the educational context in the county of Sintra.

An Evaluation Based on “Theory”

Around the concept of evaluation, several approaches have been developed; however, there is no universal definition [5]. The conceptions around the evaluation differ significantly between authors, which translates in several approaches, definitions and perspectives of evaluation in the literature [6,7]. According to Gullickson [8], all parts involved in the evaluation process should understand in what consists evaluation and quality of evaluation. This understanding starts with its definition. The inexistence of a clear and consensual definition tends to allow for the development of diverse specific definitions in order to meet the needs. Thus, it is necessary to come up with a definition that allows one to distinguish the evaluation from other activities [8,9]. In this sense, Aguilar e Ander-Egg [5] affirm that the evaluation must come from a process of systematization and planification, from values and judgements performed by those who intend to estimate about a given program or activity, in order to identify and produce data and information that are relevant to judge the value of that same program or activity, identifying problems or acting towards their correction, providing results and concrete effects [5]. It can also be said, according to Kosecoff and Fink [10], that evaluation relates to a set of proceedings that allow one to sustain the judgement on the merit of a program and provide information about their goals, expectancies and the foreseen results, the impacts and its costs.

Underlying the process of evaluation is the mobilization of a set of methodologies and steps that include activities that aim: (i) to estimate the broadness and relevance of the intervention; (ii) to ensure the accuracy of the diagnosis providing elements that grant a coherency and the conception of the intervention in the best conditions; (iii) materialize the intervention, doing an analytic and systematic approach that ensures the right usage of the environment and resources and the fulfilment of planning; and (iv) to identify and analyze the results from the intervention, determining if and in what extent changes were generated and in what extent it occurs exclusively from the intervention, questioning the efficacy and efficiency of the same intervention [11,12]. Notwithstanding this, the evaluation does not only circumscribe to achieve the objectives, but also allows the elements and entities involved in the different phases of the process to critically appreciate the work developed and the effective results and its impacts. Thus, from the evaluation one may expect judgments of value endowed with its utility [13,14]. This said, it was not intended that the evaluation of the project “The School Grows with Us” would be limited to prove the functional effectiveness of the training/capacitation program, but that it would be capable to assess and identify the reasons why the program worked, why it worked in a specific way and not in another at a given moment, if and how the functioning of the program can be improved. This means that, from evaluation, what is intended is to deconstruct the change mechanism, by importing the interactions between procedures and results [15,16]. This means that we are facing a type of evaluation that is inserted in the universe of the theory-driven evaluation [10]. In this type of approach, we use the theories that bring a greater explanatory capacity to evaluation, supporting the role it assumes for the comprehension of a certain social reality [17,18,19].

The work developed by Weiss [16] allows for the definition of a theory of change as an explanation to “how” and “why” a program works. The theory of change is then related to a cumulative and systematic analysis of the relations that are established between contexts, activities, and results [18,20], to ensure the success of the program. Some authors refer that the use of the theory of change is controversial when it comes to evaluation. If, on the one hand, some are opposed to the use of a specific theory for the program to be evaluated, because this approach implies validation and proven methodology, others state that just one theory of change is not enough in an evaluation, since it does not integrate a counter factual analysis. Nevertheless, theories of change have been used in evaluation and some evaluators have shown how useful it can be [21].

The understanding produced around the evaluation based on theory considers that this provides information that are not easily achieved through the implementation of traditional approaches. For this reason and because it aligns and/or adjusts the implicit and explicit theories that mediate from the diagnosis through the delineation of the objectives to achieve, the strategies to mobilize, the activities to be carried out and the stages in which the program is implemented, the theory of change assumes an important tool for planning and evaluating educational policies.

Enabling the involvement of the different interested stakeholders in the planning of change [15,20,22], “the theory contributes for the existence of a more transparent relationship between the evaluators and all those who, in some way, are involved in the evaluation process, allowing to better understand what is or may be at stake in that same process” [23] (p.29).

An evaluation based on the theory-driven evaluation is thus able to identify what to assess and establish a set of guidelines that provides organizations/policy makers an orientation on when and what to evaluate [24,25]. However, the construction of that information comes from a process that requires a high level of rigor implying that there is ample scientific knowledge [26] about the object to be evaluated in order to ensure the viability, efficiency and effectiveness of the implementation. In addition, the impartiality in an evaluation process must always be preserved, even if the evaluators intend to establish close relationships with all stakeholders [27,28].

The theory-driven evaluation stems first from the analysis and characterization of the context to be intervened/evaluated, pointing out the problems to be solved and the factors underlying them—indicating the eventual relationships and/or processes that are at their origin—and signaling the main actors involved. This is followed by an assessment of the coherence of the activities inserted in the program, which can generate causality, becoming then expectable that it can lead to the creation of a new context—which corroborates the theory. In the last phase, the change that was firstly projected tends to be reflected in the modification of the problems that were identified. Thus, in the case of Sintra, the factor/problem laid in the incipient level of technical and professional preparation of the operational assistants and in the lack of specific and necessary skills for the performance of their profession in a full educational logic and not only in the playground surveillance.

The training needs that were identified in the schools of Sintra—as the Municipality of Sintra carried out a survey of the training needs of the human resources of the municipality’s educational institutions—are not an isolated case. On the contrary, it appears to be a deficiency in most Portuguese educational institutions just like it is evidenced in the most recent literature. Some authors [4,29] have addressed this reality, stating that the training provided to operational assistants has been insufficient to teach them specific skills for the tasks they perform, which perpetuates a weak social image of the profession and makes it impossible for them to be active agents in the educational process.

The theory-driven evaluation implies a construction of a hypothesis to be tested in the case that: (i) the level of performance of the operational assistants can be optimized; (ii) the training and capacitation of these professionals prepares them for the performance of new and more demanding duties; (iii) the transmission of content and learning process is favored if performed in real work context.

Thus, from the evaluation that was developed, it was evident that a demanding learning process capable of deeply changing the functional profile of the operational assistants could not happen “in a vacuum”, and should be as directly as possible linked to the concrete experiences of the real work, in order to allow the receptor to relate the contents of the training with his/her personal frame of reference—this is marked by a set of experiences, involving diverse interactions with other agents from the inside and from the outside of the school organization [30].

In this sense, considering the learning context implies starting from a model that related the receptor to the content, and the context to the learning event. Although some authors warn to the inexistence of a consensual definition of what constitutes “context” [31], from the multiplicity of understandings built around the concept of learning context, it can be essentially defined as a set of circumstances that are relevant when someone needs to learn something [32].

This said, training in a real work context came to support the notion that it is easier to learn or integrate new ideas through what is already known or practiced [1]. Training in the workplace is not limited to the easy identification of factors that stimulate or block the achievement of the intended objectives. In this type of training is valorized a set of given strategies, actions and relationships between the trainers and trainees which potentializes the learning process.

Nevertheless, to intervene in the core of the competencies of the operational assistant implies the acknowledgement of the needs that were previously identified and the need to build a model that is consistent with a strategic plan of action in order to address the institutional deficiencies. The concept of competence encompasses the behavioral and action dimensions. However, understanding that the competence is the output requires comprehending that it is influenced by values, self-concepts, personality traits and motivations. Thus, competence is understood as the set of qualities and professional behaviors that mobilize the technical knowledge and allow action to be taken to solve problems, stimulating a superior professional performance aligned with the strategy of the organization [33].

As the main conclusions, we refer that: (a) a training/capacitation program, to be well succeeded, must combine the institutional needs with what the employee wants and needs to learn; (b) it is not sufficient to intervene uniquely with the professionals but also to act in the school organization in order to enable them to involve at another level, develop other activities and achieve other results; (c) a school organization benefits from the articulation and cooperation between different professional groups.

In general, this article is based on the effects of an evaluation of a specific educational project, conducted by a team of researchers/evaluators from the University, that aims to highlight the possible frameworks of the learning context as a promotor of multiple, modal and interactional ways of acquiring knowledge and competences for the plurality of the actors involved.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Method

The evaluation (ex-post) of the impacts of the training-capacitation was essentially related to the answer of two elementary questions: (i) in terms of the trainees’ learning, to what extent were the training-capacitation objectives achieved?; and (ii) to what extent has the achievement of these objectives resulted in changes or improvements in the performance of the operational assistants and in the organizational and institutional dynamics? Thus, we aimed to identify if there was a transfer of acquired knowledge to the professional performance.

We adopted mixed-methods [34] as the best way to assess the impacts of the project “The School Grows with Us”. The use of mixed methods in terms of evaluation allows one to understand the internal and external influences and the various elements that characterize and/or interfere with the process of change [35,36].

2.2. Techniques and Procedures

In a first instance, a survey was produced and applied to operational assistants.

In the survey, we explored the operational assistants’ perceptions: (i) about their participation in training actions and the contribution they consider the actions had to the improvement of their qualifications and to the performance of their duties, as well as their intention to integrate future training actions; (ii) regarding the importance of their profession, the underlying challenges and the performance of their duties; (iii) in terms of the work environment and labor relationships. The approach to the training-capacity action was supported by the analysis of the operational assistants’ perceptions regarding a set of skills, which comprised their knowledge, behaviors and attitudes, and the program’s contribution to the acquisition and/or increase in these skills. These skills integrated four spheres of analysis—Knowing, Being and Doing and also other Strategic Competencies. These skills which were grouped in the following categories:

- (i)

- Information and communication, regarding the ability to analyze, understand, produce and transmit content in the different contexts in which the respondents operate.

- (ii)

- Technical knowledge, including knowledge and application of techniques and practices, taking into account the various plans of their professional context.

- (iii)

- Technological knowledge, regarding the use and handling of technological equipment.

- (iv)

- Personal development, autonomy and adaptation, reporting on the development of self-confidence, emotional and behavioral self-regulation, knowledge and compliance with their work plan and the ability to adapt to new duties and contexts.

- (v)

- Interpersonal relationships, focusing on the interactions that operational assistants establish in different contexts with the school community, in work relationships, behavior and intervention dynamics.

The second phase involved the conduction of semi-structured interviews with the directors of the school groupings and to the responsible for coordinating the training-capacitation program, member of the Association of Teachers of Sintra, the entity responsible for implementing the training-capacitation action. The coordinator played a fundamental role, both in structuring and dynamizing the training-capacitation action, and through the articulation and mediation established between operational assistants, educational institutions and the Municipality of Sintra. The interviews with the directors of the school groupings, focused particularly on the identification of the changes verified in the operational assistants (e.g., at the individual and collective level and the development and applicability of professional skills and the changes in the relational dynamics); the effect of training of operational assistants in the school dynamic (e.g., effects on ways of action and intervention of operational assistants, capacity for problem solving in different contexts). Regarding the interview with the coordinator of the training-capacitation action, it was based on the identification of the mechanisms, difficulties, mobilized strategies related to the practical context of the training-capacitation action and also on the impacts observed on the trainees and the school dynamic during the program.

In order to analyze in more depth the dimensions of a more subjective nature and considering that these are more easily identified in environments that promote the collective sharing of perspectives and experiences, the last phase included the conduction of focus groups, each composed of operational assistants pertaining to school groupings involved in the project.

For the evaluation, the focus group technique proved to be quite appropriate, as the operational assistants were not only the object of the study, but also active elements in the process. In addition, this technique allowed us to identify possible disparities between the knowledge, practices and attitudes [37] of the operational assistants. Therefore, it made it possible to assess in greater detail the possible changes that occurred. Thus, the focus groups were carried out in order to acquire new data, by exploring the impacts and changes perceived by the operational assistants, after their participation in the training-capacitation action. It can be said that the focus groups were essentially based on three main dimensions:

- (i)

- The training-capacitation action itself—essentially addressing aspects related to the relationship and communication with the trainers, suitability and relevance of the syllabus for the real work environment. We also tried to understand how and why participation in the training and in the developed activities improved their professional performance and in which levels an immediate performance was verified. Concrete examples were shared in terms of the practices and strategies used.

- (ii)

- The profession and the work environment—particularly addressing aspects such as changes in the ways of dealing/managing the different situations or problems inherent in the work context and/or that may arise from there, relationships and articulation with other professionals in the education environment and autonomy or freedom to carry out their functions.

- (iii)

- Professional development and future prospects—addressing aspects related to personal and organizational investment to improve their professional performance, as well as the way in which the contributions of the operational assistants were incorporated into the organizational dynamic of schools, and changes (positive and/or negative) coming from this integration.

2.3. Sample

The survey was applied to 109 operational assistants from 8 school groupings in the municipality of Sintra (out of a total of 20 school groupings in the municipality). The criteria underlying the selection of the school grouping was due to the fact that the schools completed the training-capacitation action in a period considered appropriate to carry out the assessment of individual and organizational impacts (completed at least 3 months after the training-capacitation action).

The criteria for selecting the operational assistants to inquire and participate in the focus groups was related to the completion of the training-capacitation action. Once the 8 school groupings met this requirement, the sample was selected randomly (random sample). Three focus groups were performed, each composed of 8 operational assistants pertaining to 3 out of the 8 school groupings involved in the project.

The delimitation of the number of interviews and focus groups to be carried out was conducted a posteriori due to the proved saturation of the collected information [38,39].

2.4. Data Processing and Analysis

The survey was carried out via an online platform. The treatment of the data obtained was carried out through a statistical analysis program—SPSS—and in the case of open type responses, content analysis was performed. The information collected through the focus groups was also submitted to a content analysis process.

The data collection and its treatment, respected the guarantee of confidentiality and anonymity, which was followed by an encryption process for all data/content that could identify the respondents.

The survey conducted to the operational assistants proved to be very useful in understanding their assessment of the project; in direct articulation with the focus groups, it allowed an assessment of the personal, interpersonal and group impacts on the operational assistants. The interviews conducted to the school directors enriched the evaluative framework of Iscte’s researchers by allowing them to understand the organizational changes in the school context resulting from the changes in practices by the operational assistants.

The survey conducted to the operational assistants proved to be very useful in understanding their assessment of the project; in direct articulation with the focus groups, it allowed for an assessment of the personal, interpersonal and group impacts on the operational assistants. The interviews conducted to the school directors enriched the evaluative framework of Iscte’s researchers by allowing them to understand the organizational changes in the school context resulting from the changes in practices by the operational assistants.

3. “The School Grows with Us” Project: An Innovative Local Educational Policy

The project “The School Grows with Us” is part of a larger European project named “Innovative Plans to Combat School Failure” that aims to promote the students’ success by improving the school environment through training and capacitation actions directed to the operational assistants. The project, aligned with the Smart, Sustained and Inclusive Growth, is part of the 2020 European Strategy and comprises the principles that consecrate the economic, social and territorial development to promote Portugal between the years 2014 and 2020 (Portugal 2020). This project, presented under the Program of Action of the Pact for Development and Territorial Cohesion in the Metropolitan Area of Lisbon, aims to reduce the rate of primary and secondary school students with negative results, as well as to reduce the retention and drop out rate. In this sense, the project “The School Grows with Us” promotes the combat to school failure in complementarity with the plans to improve the Educational Territories for Priority Intervention (TEIP) and the National Program for School Success (PNPSE).

As it is a public local initiative, it expresses a change in the political-educational paradigm, by placing adult education and training as one of the priorities for the local government programs. Due to the territorial extension and the socioeconomic diversity of the county of Sintra, the intervention combined different educational territories and specific areas of intervention which were defined according to their characteristics and main needs identified.

In addition to expressing a deep change on the governmental educational politics in Portugal resulting from the empowerment of the counties, the innovative character of the project consists of promoting the role of the operational assistants in schools. This promotion assumes a greater relevance in the construction of new educational projects in their mission to promote a safe and educational space of quality for all: students, professors, parents and operational assistants. Thus, promoting the improvement of the students’ performance necessarily involves the improvement of the performance of the operational assistants, which observe and act in the school compound, especially during recess, where professors and parents are not present. In this sense, this project came to open the horizon to the combat of school failure by valuing the role of a professional group that is not usually considered. Essentially it is a matter of transforming them from mere “surveillants and cleaners” into effectively relevant educational agents.

Regarding the profession of operational assistant, which has been modified through changes in the political-educational environment, new practices are being added, but new responsibilities, requirements and challenges have also been passed over. As it is an occupation that is easily associated with low levels of qualification and low income and to which persists a lack of attention to their training needs, a project specifically oriented to these workers is an innovative aspect because of its broadness and an intervention structure was created to cover all operational assistants of the schools in the municipality of Sintra.

By listening to the school groupings’ representatives, it had been possible to identify a priori a set of essential dimensions for priority intervention: (a) inclusion (of cultural and religious minorities and of students with health special needs); (b) conflict management (in the inter-relational aspect between students, operational assistants, professors–family); (c) teamwork; (d) intervention in the context of the school library, learning centers, sport pavilions, cafeteria, outdoor spaces and other areas related to the school institution; (e) assertive communication; (f) first-aid; and (g) absenteeism by sick leave. Thus, to intervene near the operational assistants, we sought to increase their levels of awareness and skills for collaborative work, to develop literacy skills, to capacitate for a context of change, exercise self-reflection and continuous assessment. During the training and capacitation actions the operational assistants were helped in the sense of acknowledging their contribution to the educational environment and to comprehend their potential not only as professionals but also as human beings.

The training component lasted 30 h and focused on sharing the trainees’ professional experience and personal perspectives regarding pre-defined subjects. This modality allowed in a later phase, to approach the belief and values system and the different types of families and students.

The capacitation aspect which lasted 50 to 80 h—divided into 14 modules, each corresponding to 2 h of theoretical-practical classes and 2 h of autonomous work in real work context under supervision—deepened the interaction techniques and communication through the mechanisms of personal and collective development. In addition, the capacitation aspect focused on language issues, approaching aspects such as generalizations, distortions, omissions, and prejudgments in order to develop a coherent and contextualized discursive practice. Regarding communication practices for conflict management and other non-violent communication mechanisms, it has been possible to approach the emotional management and its dynamic. These were the main deficiencies found in the diagnostic phase, which proved to be worthy of special attention due to its influence at the level of the relationships and interactions between the operational assistants and the students and their families. It was also addressed the digital financial literacy and the importance of lifelong learning always associated with practical exercises as a pedagogic strategy.

Through a dynamic of teambuilding, which lasted 6 h, it had been put in practice a cooperation game aimed to improve communication and the development of necessary skills not only directed to their professional reality but also to the personal as social life. (It refers to a group dynamic that aimed to gather, at the final phase of the training-capacitation program, the different groups of professionals from each school grouping of the county. Professors, members of the directive board and operational assistants were present. This dynamic aimed to promote a spirit of cooperation, reflexive capacity and self-evaluation, the construction of a collective understanding that “School Grows with Us”, as well as a joint reflection about the challenges of change). Lastly, the trainees were capacitated to act in emergency situations by being trained for basic-life support so they can act in cardiorespiratory arrest and/or resuscitation. It is important to note that all measures were followed by collaborative tasks and the physical and psychological well-being was also approached through mindfulness exercises. (It is related to an activity that aimed to focus on body and emotion consciousness as a skill to develop. It is a matter of understanding the body, “body-scan”, to promote the exercises of listening, feeling, and understanding it). The trainees were evaluated throughout the program based on oral presentations.

4. Design and Organize the Learning Context

Approaching the learning context implies knowing that several actors are present in it. A project of learning in context requires a prior and solid preparation that brings together professionals from different areas of action: the institution, promoter of the project; the entity that carries it out; and the evaluators. Thus, after identifying the field of intervention, it is necessary to include professionals that are qualified to train groups or subgroups, assuring adequate learning initiatives.

Organizing the learning context implies the prior identification of main skills which includes the adaptation capacity, not only of the strategies and resources to mobilize, but also of the professionals and the targeted audience of the project.

Putting in practice a learning context of this nature, it is comprehended that there is a plurality of modalities in which the learning context occurs. This allows for the discussion of the plasticity, broadness and multidimensionality of the concept of learning context. The learning context is rarely unilateral or linear as it assumes an inter-relation between all the intervenients in the process. In this sense, the importance that the context plays in the different phases of the assessment must be recognized, and must always be considered not only for the decision-making process but also in the design of the assessment and essentially in the analysis and interpretation of the results. The internal and external context in which the evaluation is inserted is fundamental, because its understanding allows one not only to identify needs for adjustments to the research design in order to consider the specificities of the object to be evaluated, but also to explain the relationship between processes and results [35]. In this sense, we understand that the learning context is intrinsically associated with the evaluation itself. That is, the promoting entity, in this specific case, the municipality of Sintra, evaluates the quality of the proposal, the researchers evaluate its execution and take their conclusions, the operational assistants evaluate the contribution of the training action to which they were submitted. This way, the interrelation in the learning context takes place between the parties involved and it contributes to the assessment complementing it, even if in different ways.

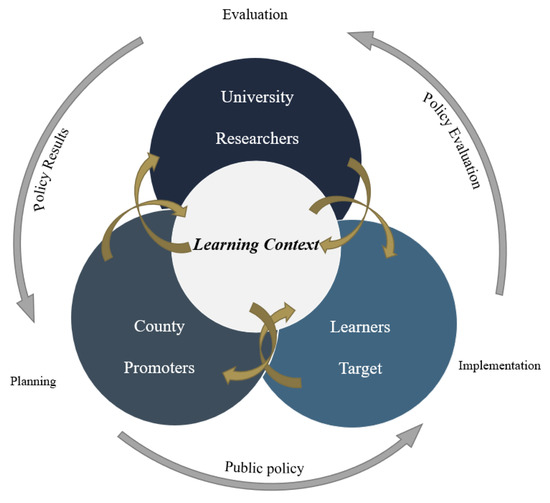

In order to illustrate this statement, see the Figure 1, which demonstrates the dynamic related to the learning process in the real work context. From the objectives, the project design and passing by the development of its implementation, we outstand the power of initiative and action of the institutional/political organizations that suggested the project. They are the ones who hire the higher education institution to implement the project evaluation, specially near the target audience: the operational assistants.

Figure 1.

Inter-relations dynamic diagram of the learning context in the evaluation of public policies. Source: Authors.

In the phase of the evaluation, the necessity to adapt to a double context, on the one hand to the context where it was developed and on the other hand to who was involved, is revealed. In this sense, we registered a learning process both by those who were responsible for the evaluation, and by those who were the main object of this traning-capacitation action. In a third phase, the presentation of the results coming from the researchers’ analysis are the same reported to the institutional organism promoter of the project. This last reflects upon the evaluation and the results of the project that it decided to apply, gauging its quality and suggesting changes for a new project development, if needed. Thus, the learning context assumes the function of a central engine that promotes and consubstantiates the management of an educational project such as this one. It is then considered that the learning context touches all the intervenients, even if in different moments and not only those for whom the program was designed in first place.

5. Results

5.1. “The School Grows with Us”: Impacts from the Training-Capacitation Action

The first objective of the training-capacitation action is to generate a change in the knowledge and behavior plan, in order to achieve a level of development that surpasses the initial stage to be reflected in the work practical context. The success of the training-capacitation action is partly due to its flexible and personalized character. It was conducted not only by taking into account the abstract needs inserted in the intervention plan, but was also adjusted to the trainees, considering their criticisms, interests, availability and difficulties, which triggered a greater receptivity and therefore greater productivity and better results.

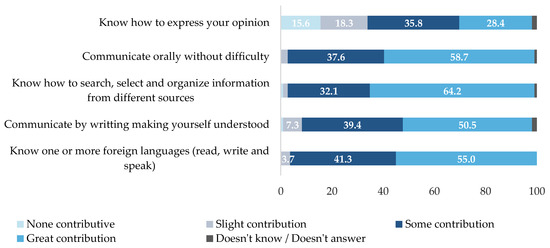

The contribution to the increase in the levels of literacy (Figure 2) of the operational assistants was notoriously essential in the domains that are considered indispensable for the performance of their functions. These domains include the sphere of information and communication (through the development of the analysis capacity), the sphere of understanding, production and content transmission in the different contexts of action that are included. This last domain is reflected, for instance, in situations of communication with foreign students and their families, escorting the users of the educational institution or even to know how to express their opinion (64.2% indicated that this was of some to great contribution) and communicating both orally and by writing (58.7% and 50.5%, respectively, stated that this was great contribution).

Figure 2.

Contributions of the training-capacitation action for the acquisition of information and communication skills (%). Source: Survey to the operational assistants.

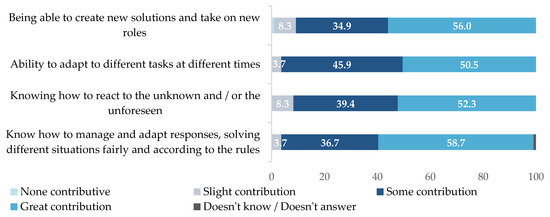

The acquisition and/or reinforcement of technical-professional knowledge, such as the application of basic life support techniques and the assistance to students with special health needs, the awareness for the rights and duties of all users of the school—knowledge indispensable for carrying out the operational assistants’ day-to-day job—are identified by them as new and important acquired skills. It should be noted that 58.7% of the surveyed operational assistants referred that the training-capacity actions contributed significantly to the management and adaptation to the responses they are faced with daily, resolving different situations fairly and in accordance with the norms (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Contributions of the training-capacitation action for the acquisition of autonomy and adaptation skills (%). Source: Survey to the operational assistants.

Regarding practices and care techniques, 60.6% reveals that it had a major contribution. Regarding technological knowledge, the development of technical skills is also identified (69.7% indicates that it is already an acquired skill). When rotation between posts is necessary, this often leads to constraints in the management of employees by the school directors given the difficulties faced by a large portion of operational assistants in the handling of technological equipment. By focusing on this matter, the training-capacitation action also made it possible to demystify some concepts associated with services where the use of technological equipment is constant, such as the stationery store or library, whose operational assistant who works there tended to be perceived as more competent. Additionally, on the other hand, it allowed for reversing the resistance or fears of operational assistants who did not intend to be deployed to these services because they associated them with requirements for knowledge and skills they did not have.

Although it is pertinent to reinforce or deepen some areas of technical and professional knowledge continuously, guaranteeing the progress and updating of contents, the knowledge increase of operational assistants in these areas has led to the enhancement of their adaptability and their confidence levels and participation, which resulted in better performance both individually and institutionally.

The range of changes observed is more visible in what refers to the acquisition and/or development of personal, behavioral, and social skills, in comparison, for example, with techniques. By participating in the training-capacitation action, facing it as an investment for their personal and professional growth, the operational assistants faced “transformative” learning. In this sense, it resulted in the (re)thinking of a new set of practices and behaviors diverging from what these professionals had being shaping according to the situations they experienced during their work performance and thought would be the most appropriate. The impact of this learning was perceived by the operational assistants when they identified deep changes in their ways of being, thinking, acting, and feeling, transposing a more valuable look at themselves and the jobs they perform.

The changes in the communicational and interventive dynamics and the promotion of a greater commitment to the harmonious resolution of conflicts caused effects not only in the relationship between co-workers—previously involved in situations of friction, disagreements or intransigencies—but also in the work environment and interpersonal relationships that are established daily with the other actors that integrate the school context. They also demonstrated a greater cordiality in the contact with members of the school boards, with students and with the families, which consequently impacted on the image of the school.

During the evaluation, the operational assistants and the management of the school groupings noted the adoption of a posture oriented towards cooperation, showing a greater openness to share perspectives, experiences and knowledge, which describes a scenario of increased proximity and availability—even among elements that had conflicting relationships. In this sense, among the verified transformations, it is worth mentioning a greater capacity for analysis and to shape their reactions when facing unforeseen or unexpected circumstances and (or in anticipation of) specific problems, for which the application of self-control techniques learned from the training-capacitation actions demonstrated its efficacy. The expression of dissatisfaction became more thoughtful, timely and polished. These acquired skills are extended to other social contexts in which the operational assistants are inserted, thus having an impact on their family relationships and on their emotional well-being, as they are more able to dissociate themselves from possible problems caused by and at work.

If prior to their participation in the training-capacitation action the operational assistants did not express an interest in presenting their points of view, or suggestions for improvement, or simply were not able to do so, they acquired a greater predisposition for proactivity and criticism and initiative, also showing a greater capacity for decision making and, as a consequence, greater autonomy. This evolution is noticeable by observing that these professionals put into practice the knowledge and techniques acquired in the training-capacitation action, revealing the transfer of learning to the workplace, as intended by the municipality of Sintra.

As it is a professional group that often feels less valued and that perceived participation in training actions exclusively accessible to restricted professional groups and/or with higher qualification levels, attending a training action unique and exclusively designed for them generated a feeling of appreciation, enhancing its performance. This is a significant aspect, since for many of the operational assistants this training-capacitation action was fundamental, and for some even more so as it was the only one they benefited from or the most extensive since the beginning of their career. The training-capacitation action contributed, on a large scale, to the collective increase in self-esteem, satisfaction and motivation for the work environment and for the individual recognition of their own capacities and aptitudes. In this sense, it also allowed the school boards to better understand the capabilities and limitations of operational assistants, favoring a balanced management in regards to their allocation in services more oriented to their profile—which, in complementarity with the assignment of new (or more) tasks, came to be seen by these professionals as a vote of confidence by the school board. The changes in the organizational dynamics of the schools also allowed us to reinforce the sense of tolerance and a more objective view on the organizational and institutional (in)capacities, by awakening to the understanding of the need for flexibility of the operational assistants and their sense of usefulness, combined with the understanding that their absences from work have an impact on the functioning of schools (something that only in the medium to long term will it be possible to assess widely).

On another level, the development of the teambuilding dynamics that integrated some members of the teaching teams and the school boards provided, as main contributions or benefits, the creation or strengthening of ties. Because it was so enriching, it led some of the school groups to consider the future reproduction of the activity in a model that maintains the involvement of both professional groups, in order to promote or maintain an environment of cooperation and mutual appreciation.

The assessment revealed the high importance that the attributes of the profession can have for operational assistants themselves, and that monitoring the growth of students, the assistance they provide and the connection they create with them are the main reasons why they perform the profession, them being those who most directly recognize the work they do in schools. This is true even if it is a profession that is associated with multiple duties and responsibilities, but with reduced salaries, which brings to mind the centrality of work in society and its identity and integrative functions, and its role in reaching satisfaction and personal and professional fulfillment.

The constraints felt at a time of a global pandemic caused by COVID-19, implied some changes to the format initially thought for the training-capacitation action, impelling periods of confinement and the use of digital means for its implementation. Nevertheless, the feasibility of activities was guaranteed through a permanent contact and interaction that allowed for the maintenance of routines and proximity between peers at a time in which face-to-face labor relations were compromised. Learning in (and in this) context, met the needs of educational institutions and the needs of operational assistants, and the process of self-assessment/continuous discussion in each activity made it possible, through moments of reflection, to correct and guide behaviors and attitudes as close as possible to the events, which facilitated and streamlined the assimilation of new behaviors. In addition, from the evaluation of the project «The School Grows with Us» emerges the notion, almost unanimously, that the training-capacitation action fulfilled the objectives outlined that guided the intervention project and changed the lives of the operational assistants who work in it and that participated, whose positive effects, measured in the short term, are expected to last. In short, in this training action, the institutional, labor and individual dimension were contemplated, in which the contents were transmitted and learned in a way considered correct by the educational agents involved, and at the right time, taking into account the intervention needs and the challenges that schools face daily.

5.2. Evaluation of the Results for Future Training-Capacitation Actions in Context

The evaluation process of this educational project is marked by a methodological design that intentionally aimed to combine several techniques and instruments of collecting and analyzing data, allowing us to consider and reflect in depth about multiple dimensions of analytical interest, and that eventually would not be addressed in a smaller evaluation. A multi-method analysis revealed aspects that go beyond institutional weaknesses and needs, by also incorporating the subjective dimension. Listening to the perceptions and perspectives of directors and operational assistants face to face and confronting the perspectives made it possible to identify the causes and consequences of these same weaknesses and needs, tracing guidelines of action for the future.

When developing (future) training activities in context, educational institutions and their training entities must consider that:

- (a)

- Learning must also be perceived as necessary and must create an impact on the beneficiaries.In this specific case, the targeted audience has, in the first place, to perceive that the fruit of their participation in the training action benefits them, directly and indirectly. Directly given the enhancement of their performance and the increase in their levels of autonomy (despite the absence of external rewards, such as salary increases), and indirectly as the institution, by benefiting from a more optimized performance of its employees, can recognize their abilities, assigning functions that best suit them.

- (b)

- The learning process becomes more effective when the recipients are involved in a process that generates change and allows the identification of concrete transformations. The content is more easily assimilated if there is a feeling of involvement.

- (c)

- The contents and technical knowledge are more easily learned when articulated with the practical component at the same time. The relationship between knowledge and action is reinforced since the behavioral correction is immediate and in loco.

- (d)

- If the sensation of evaluation by third parties is put in second place, performance levels are optimized. The learning process should remove the feeling of fear caused by the assessment, mostly if there is a perception of vulnerability of keeping the professional positions already held. Training in a real work context by encouraging a critical spirit and self-correction streamlines the learning process and consequently increases the receptivity to learn and assimilate new behaviors and contents without pressure.

Planning an intervention in an educational context when oriented towards specific professional groups implies the necessity to assume that it should not be guided by bureaucratic needs, which generally resort to highly standardized operating mechanisms, which disregards the framework, characteristics and effective needs of people and the institutions in which it is intended to intervene. Moreover, it should be taken into account that the developments produced have repercussions in peoples’ lives and institutions [27]. In the case of Sintra, the malleability of the interventional plan, meaning a plan that introduced the necessary flexibility to adequately make a change, not limited to the implementation of a sequential set of strategies dispersed according to the political-educational objectives to be achieved, demonstrated that paying attention to the diversity of contexts allows one to reduce obstacles and the resistance to development.

This provides not only the construction of local systems able to respond to different educational needs of territories, but also allows one to design a set of strategies of intervention that consider and involve the educative community in general.

6. Discussion

It is important to reflect about the role of operational assistants as agents who establish close connections with students and are present throughout their school path, as this connection ends up being more pronounced than the one expected with the professors given their rotation over the years. Thus, assistants spend much more time, for more years, in contact with each student. Our results confirm the relevance of operational assistants in the school context as they are more present in the various social spaces of the school, where there are countless, differentiated and significant interactions with and between students, to which professors do not have access very often. Given that, in the Portuguese tradition, the responsibility for these spaces does not rest with the professors, limiting their responsibility essentially to the classroom, but since it is a responsibility that is assumed by the educational institution, it is essential that the operational assistants are able to upgrade their duties and their real mission at school.

It should be noted that it is not enough to train, but also to formally recognize this training by considering the ambitions of these professionals. Thus, regarding the valuation and career development of operational assistants, they are constantly required to improve their skills and competencies, which do not correspond to their level of remuneration and professional progression.

Another relevant aspect concerns the increasing importance that municipalities assume in the construction, implementation and evaluation of local educational policies. Municipalities should use their political power to intervene in various areas, such as the one of education, potentializing the resources they have access to. In this sense, it is important to highlight the importance of funds for local development such as the one applied to the project “The School Grows with Us” by the Sintra municipality.

The training and capacitation actions, although important, can only be realized if supported by a financing system that allows it. We highlight the Sintra municipality for having the needed financial means (in conjunction with funds from the European Union), which makes it an example of what should be expected from an effective management of the right to education and that combats school failure.

Thus, the understanding that the operational assistant can also be an agent that operated for change on the educational context was underlined since the conception of the global intervention project—an aspect that was revealed to be beneficial, recognizing the capacitation of the operational assistants as a motor for the improvement of their professional development as well as the institutional development of the schools of the municipality of Sintra.

The evaluation of the impacts of the project came to confirm its adequacy and the benefits of learning in a real work context. Articulating practical exercises with the new acquired skills demonstrated an appropriate tool to capacitate with efficacy this professional group, responding to the specific problems that needed intervention.

Aside from increasing the levels of performance and efficiency, sustained by the significant increase in technical and professional knowledge (about subjects poorly consolidated or that were completely strange), the training action in the work context contemplated socialization processes, integration and participation in which the learning process was not only focused on the organizational context but were enlarged to the different plans of social life of the operational assistants, namely their self-valorization.

It is understood that the training activities in the work context acted on the (re)creation of conducts and fostered the sharing of perspectives and experiences and consequently promoted a substantial development of socio-behavioral skills—which was also of great importance at the level of labor relationships, productivity and well-being, were not work one of the essential places of identity construction, integration and socialization [40,41,42].

Furthermore, considering that, in the school context, operational assistants do not perform functions in isolation, the training actions should not only contemplate the specific contents related to improving the performance of these professionals, but also consider the relationships that this performance establishes with other functions within school and, in particular, between operational assistants and professors. Since performance does not depend solely on the worker, training in real work context empowers not only those who were targeted, but also other groups in the same organization. In order for operational assistants to enhance their performance, it is necessary that both the teaching team and the management staff are aware of their skills, knowledge, experience, and who values and accepts them, incorporating their (new) contributions in the routine of the school organization. Translating into an opportunity to act on the collective understanding that life at school implies the real involvement of all, training-capacitation actions in schools should be an investment that takes into account the integrated objectives of organizations and not only directed to specific professional groups that may compartmentalize the performance of school agents even more.

It should be noted that the evaluation concentrated on itself a double application. This means that it not only allowed for elucidating the most appropriate strategies to implement, in function of the intended change, but also acted as a driving tool of the learning context, by enabling agents to confront, through the mobilized methodologies, with the advantages, disadvantages and potentialities of the training-capacitation actions. It is in this process of confrontation with reality that one seeks to change, that the primary function of evaluation serves its useful purpose, (self) correcting and coherently guiding the strategies and actions that must be carried out, improving the internal management of the project and the adequate use of means and resources to achieve the desired objectives. The evaluation process is itself a learning process. An assessment that integrates a component of collaborative reflection, promotes the production of transformative individual and organizational learning [43]. An assessment that does not generate learning, for all stakeholders, is not an assessment that promotes any change.

Moreover, it should be noted that the implementation of training actions is often perceived as a bureaucratic obligation, which is subjected to mere and superficial inquiries of the recipients’ assessments. It is understood that one of the reasons for this to happen is due to the fact that those responsible are not familiar with the principles and procedural logic of evaluation [44]. At this level, it is imperative to alert to the understanding of how important it is to continually train and qualify these professionals for the performance of a profession that is under several transformations. It is also reinforced that the evaluation has a fundamental role, since, in this context, the reassessment of needs allows us to engage at the level of personal and technical-professional development, by acting on the maintenance of the practices and the consolidation of the acquired skills and learning, thus guaranteeing the sustainability of the demonstrated results. In short, training and capacitation actions, whatever the professional group targeting, only achieves sustainable and lasting results when undertaken under a broad and robust evaluation program, based on the very context in which the professional activity is developed.

7. Conclusions

Schools now more than ever recognize that operational assistants are an important element in its context. However, even with an understanding of the important role that the operational assistant has in the construction of an educational environment of quality, very rarely is this professional perceived as an educational agent. Therefore, we face the need for a reconfiguration process of the functions these professionals perform, that is, a switch from their auxiliary and instrumental duties to more intrinsically educational ones.

The different professionals that integrate the school context cannot limit themselves to their specific functions but should be flexible and have the ability to adapt and articulate with other professionals in the organization. We refer, mainly, to a stricter relationship and cooperative between professors and operational assistants, reducing therefore the asymmetries present in the hierarchal relations between these professionals. The existence of closer relations translates into more directed and adjusted ways of action and intervention by both professional classes, which, based on the sharing knowledge and experiences, implicitly leads to a reciprocal appreciation and with it a good educational environment promoter of equity.

It is important to affirm that the institutions that analyze and evaluate this type of project, namely universities, should maintain a proximity to the promoting entities of these projects. It is fundamental that a constant review and evaluation of the quality of the educational politics exists, allowing for the observation/follow up of the measures applied [45]. This way, we believe that the feedback given to the promoting institution of this project, the municipality of Sintra, is the most relevant aspect together with the impacts of the training-capacitation action near the operational assistants. Without evaluation, it is not possible to understand the reality before and after the development of a project, fundamental to the consolidation of solid and effective public policies. The appreciation of the evaluation of public policies, from the intervention programs to the local level, is not reduced to a mere statistical measurement of the most immediate effectiveness of actions. It is necessary to determine the different plans and domains of the impacts of the training-capacitation action, and its potential to produce an effective change, not only in the working sphere, but in the life of these professionals, and the effects produced by it; these changes were immediately recognized by the operational assistances and the school’s boards.

The evaluation of educational projects and policies has, in previous years, proved to be one of the concerns of central and local governments. Considering the growing complexity that follows the creation of public policies in the most varied fields and its process of implementation and evaluation, it is worth mentioning the integration of specialized professionals, which are aware of the (complex) social reality and its social and political problems [46], in order to use theory as a reference and tool to evaluate and measure the validity and the reach of conclusions built in the evaluation process. This dynamic is not only indicative of a greater visibility and importance given the expert knowledge which contributes to increase the participation and intervention, but also of a greater recognition of science, of its role and value. This way university institutions see that their role has a higher importance to research, analyze, evaluate, produce, and disseminate new knowledge.

The role of higher educational institutions in evaluating educational policies, whether of local, regional and/or national focus, should be reinforced, which will bring mutual benefits for the institutions and the agents involved. The contemporary educational challenges are still diverse and demand better tools for the evaluation of the processes and impacts. The use of an integrated perspective of the learning context has revealed to be pertinent, consolidating scientifically the evaluation of public educational policies.

The team of researchers responsible for the evaluation of the educational public policy implemented in Sintra concluded that it contains major potential to change the school system, not only with regards to a set of communication and information skills but also to develop new technical and professional, personal and interpersonal skills acquired by the operational assistants. They started to occupy a new recognized importance, being given more value in the relationships with the rest of the educational agents, namely the school boards, teachers, students and their families. The recognition of operational assistants, which occurred thanks to the investment that the municipality of Sintra attributed to them when they decided to implement the project «The School Grows with Us», produced impacts in schools that goes beyond the operational assistants, specifically in the way school boards expanded their horizons regarding the competences that these professionals can perform in the school. This valorization of the operational assistants, shared by an increasing number of educational agents, powered by a significant number of school groupings, increased qualitatively the human resources of the schools of Sintra, which may mean, in the short-to-medium term, a visible improvement in the academic success of the students residing in this Portuguese municipality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Q., L.C. and N.N.; methodology, L.Q.; software, L.Q.; validation, L.Q, L.C. and N.N.; formal analysis, L.Q.; investigation, L.Q.; resources, L.Q.; data curation, L.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Q.; writing—review and editing, L.Q, L.C. and N.N.; visualization, L.Q.; supervision, L.C. and N.N; project administration, L.C. and N.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to the Municipality of Sintra for providing all the necessary conditions for developing this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- O’Connor, B.; Bronner, M.; Delaney, C. Aprender no local de trabalho. Como apoiar a aprendizagem individual e organizacional (Learning in the Workplace. How to Support Individual and Organizational Learning); Instituto Piaget: Lisbon, Portugal, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, H. L’enjeu théorique des processus d’apprentissage en Economie. Le cas de la production des compétences au Portugal (The Theoretical Stake of Learning Processes in Economics. The Case of Skills Production in Portugal); Université Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne: Paris, France, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, M. Auxiliares de Acção Educativa: Poderes ocultos na escola? (Educational Assistants: Hidden Powers at School?); Universidade do Minho, Instituto de Educação e Psicologia: Braga, Portugal, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Carreira, J. A importância da formação na melhoria do desempenho dos auxiliares de acção educativa (The Importance of Training in Improving the Performance of Educational Assistants); Universidade Aberta: Lisbon, Portugal, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar, M.J.; Ander-Egg, E. Avaliação de serviços e programas sociais (Evaluation of Social Services and Programs); Editora Vozes: Petrópolis, Brazil, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, D. Para uma compreensão das relações entre avaliação, ética e política pública (For an understanding of the relationships between evaluation, ethics and public policy). Revista de Educação PUC-Campinas 2018, 23, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ala-Harja, M.; Helgason, S. Em direção às melhores práticas de avaliação (Towards best assessment practices). Revista do Serviço Público 2000, 4, 5–59. [Google Scholar]

- Gullickson, A.M. The whole elephant: Defining evaluation. Eval. Program Plann. 2020, 79, 101787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christie, C.A.; Thomas Lemire, S. Why evaluation theory should be used to inform evaluation policy. Am. J. Eval. 2019, 40, 490–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosecoff, J.; Fink, A. Evaluation Basics. A Practioner’s Manual; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra, I. Fundamentos e Processos de uma Sociologia da Acção. O Planeamento em Ciências Sociais (Foundations and Processes of a Sociology of Action. Planning in Social Sciences), 2nd ed.; Principia: Parede, Portugal, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, S. Practice makes better? Testing a model for training program evaluators in situation awareness. Eval. Program. Plann. 2020, 79, 101788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbier, J. A Avaliação em formação (Assessment in Training); Edições Afrontamento: Porto, Portugal, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ozeki, S.; Coryn, C.; Schröterb, D. Evaluation logic in practice Findings from two empirical investigations of American Evaluation Association members. Eval Program Plann. 2019, 76, 101681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.-T. Theory-Driven Evaluations; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, C. Theory-based evaluation: Past, present, and future. New Dir. Eval. 1997, 76, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, S. Theory-driven program evaluation in the new millennium. In Evaluating Social Programs and Problems: Visions for the New Millennium; Donaldson, S., Scriven, M., Eds.; Routledge: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 109–144. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, C.H. Evaluation Research: Methods of Assessing Program Effectiveness; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Shadish, W.; Cook, T.; Leviton, L. Foundations of Program Evaluation: Theories of Practice; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, J.P.; Kubisch, A.C. Applying a Theory of Change Approach to the Evaluation of Comprehensive Community Initiatives: Progress, Prospects, and Problems. In New Approaches to Evaluating Community Initiatives: Theory, Measurement, and Analysis; The Aspen Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- DuBow, W.M.; Litzler, E. The development and use of a theory of change to align programs and evaluation in a complex, national initiative. Am. J. Eval. 2019, 40, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M. Utilization-Focused Evaluation, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: London, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, D. Acerca da articulação de perspetivas e da construção teórica em avaliação educacional (On the articulation of perspectives and theoretical construction in educational assessment). In Olhares e Interfaces: Reflexões Críticas Sobre a Avaliação; Esteban, M.T., Afonso, A.J., Eds.; CORTEZ EDITORA: São Paulo, Brazil, 2010; pp. 15–44. [Google Scholar]

- Funnell, S.; Rogers, P. Purposeful Program Theory: Effective Use of Theories of Change and Logic Models; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA; Wiley: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, R.; Mackinnon, A. Planificando el cambio: Usando una teoría de cambio para guiar la planificación y evaluación (Planning for Change: Using a Theory of Change to Guide Planning and Evaluation); GrantCraft, The Foundation Center: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- King, J.; Ayoo, S. What do we know about evaluator education? A review of peer-reviewed publications (1978–2018). Eval. Program. Plann. 2020, 79, 101785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, D. Avaliação em educação: Olhares sobre uma prática social incontornável (Evaluation in Education: Views on an Essential Social Practice); Editora Melo: Pinhais, Brazil, 2011; p. 216. [Google Scholar]

- Chelimsky, E. Balancing evaluation theory and practice in the real world. Am. J. Eval. 2013, 34, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, J. Práticas Educativas e Organização Escolar (Educational Practices and School Organization); Universidade Aberta: Lisbon, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Westera, W. On the changing nature of learning context: Anticipating the virtual extensions of the world. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2011, 14, 201–212. [Google Scholar]

- Dohn, N.B.; Stig, B.H.; Klausen, S.H. On the concept of context. Educ. Sci. 2018, 8, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, A. Learning contexts: A blueprint for research. Interact Educ. Multimed. 2005, 11, 127–139. [Google Scholar]

- Câmara, P.B. Dicionário de Competências; Editora RH: Lisbon, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; SAGE Publications, Inc.: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Newton-Levinson, A.; Megan, H.; Jessica, S.; Gaydos, L.; Rochat, R. Context matters: Using mixed methods timelines to provide an accessible and integrated visual for complex program evaluation data. Eval. Program. Plann. 2020, 80, 101784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poth, C.N.; Searle, M.; Aquilina, A.M.; Ge, J.; Elder, A. Assessing competency-based evaluation course impacts: A mixed methods case study. Eval. Program. Plann. 2020, 79, 101789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Åkerblad, L.; Seppänen-Järvelä, R.; Haapakoski, K. Integrative strategies in mixed methods research. J. Mix Methods Res. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, I. Pesquisa Qualitativa e Análise de Conteúdo. Sentidos e Formas de Uso (Qualitative Research and Content Analysis. Directions and Forms of Use); Principia: São João do Estoril, Portugal, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, G.; Naville, P. Tratado de Sociologia do Trabalho (Sociology of Labor Treaty); Cultrix: São Paulo, Brazil, 1972; Volume II. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, J.; Rego, R.; Rodrigues, C. Sociologia do Trabalho: Um aprofundamento (Sociology of Work: A Deeper Approach); Edições Afrontamento: Porto, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sainsaulieu, R. L’Identité au Travail; Presse de la Fondation Nationale des Sciences Politiques: Paris, France, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Deane, K.L.; Dutton, H.; Bullen, P. Theoretically integrative evaluation practice: A step-by-step overview of an eclectic evaluation design process. Evaluation 2020, 26, 98–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capucha, L.; Nascimento, C. Coordenadas GPS: Um instrumento de avaliação (GPS Coordinates: An assessment tool). Sociol. Online 2017, 14, 29–57. [Google Scholar]

- Calmon, K.M.N. A avaliação de programas e a dinâmica da aprendizagem organizacional (Program evaluation and the dynamics of organizational learning). Planejamento e Políticas Públicas 1999, 19, 3–70. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastião, J.; Capucha, L.; Martins, S.C.; Capucha, A.R. Sociologia da educação e construção de políticas educativas: Da teoria à prática (Sociology of education and construction of educational policies: From theory to practice). Revista de Sociología de la Educación RASE 2020, 13, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).