1. Introduction

Educational innovation is a top priority worldwide because it is considered pivotal to promoting competitive and inclusive economies [

1]. Within that context, information and communication technologies (ICTs) could have a key role as possible enablers of innovation in education and training. Innovative educational projects appear to be increasing in several countries [

2]; however, some studies [

3] show that education systems are not applying ICTs to their full potential. In higher education, pedagogical innovation and the use of digital resources are still “in the early stages of development” [

4] (p. 1054); and some teachers are still reluctant or at least unenthusiastic about using ICTs [

5].

This scenario also applies to Portugal. Several studies reveal that many teachers still use traditional learning models in most national higher education programs because classes are based on expositive and curriculum-centered pedagogical practices and students assume little responsibility for their own learning process and tend to mobilize memorization techniques during evaluations [

6,

7]. This has slowly been changing since the Bologna Declaration, but researchers found that learning methods are still far from student-centered education in our country because many teachers and students are still not prepared for these new pedagogical practices [

2].

The burst of the COVID-19 pandemic last March brought this reality back to light when governments, teachers, students, and families were pushed to quickly learn how to mobilize technologies to engage in online lectures, enhancing deficits in accessing and using ICTs. From primary to higher education, everyday classes were very quickly adapted to the digital world. But we now know that some students were left out of digital school, consequently increasing socioeconomic differences, and that some teachers struggled to use ICTs proficiently in order to successfully conduct their classes online; that means that for many teachers and students this “new” online school was not a good experience [

8].

In higher education, programs usually include practical classes, and for some areas of expertise, those hands-on moments are crucial to training students to face real-life problems in the future. All medicine programs, for example, put their students through intense hours of hands-on sessions such as, for example, rotations in hospitals, internships, etc. [

9]. Veterinary programs also provide hands-on sessions on and off campus. This added difficulties in creating credible solutions because higher institutions lack the technologies that could help teachers provide effective hands-on sessions with simulators (similar to what is used to train pilots, for instance), 3D images, and so on, many of which are already used in some human medicine programs. The main goal of this brief study is to analyze the role ICTs played in learning models before and after COVID-19: How did teachers and students adapt? What were the outcomes of online lectures in veterinarian programs? Could we expect learning models in these programs to increase the use of digital resources such as, for example, mobile applications to learn about animals’ anatomy and how to proceed in medical interventions in the future?

ICTs are sets of technological resources used to gather, distribute, and share information that facilitates automation and communication, whether in business, research, or education. The rapid advances in technology are changing the way education is planned and implemented and the way children learn, communicate, and socialize all around the world [

10]. This justifies the increasing interest of national governments, international organizations, researchers, and schools in applying digital technologies to improve learning and teaching. By using ICTs, teachers can provide students with opportunities to actively engage in learning and to build knowledge. Technologies enable flexible teaching methodologies that could help to reach disadvantaged groups and also enable the processes of engaging and challenging students with subject matters as real-life problems, of stimulating communication and discussions about the subject matters, and of “learning by exploring, experiencing, discovering, constructing, reflecting and acting” [

11] (p. 105).

As such, ICTs can play an important role in the process of transforming education by enabling it but are not the key solution. The use of ICTs brings many challenges to teachers because it highlights the need to reorient towards building more constructivist learning environments and also the need to learn how to use new technologies that are already being used by students with proficiency. Teachers are confronted with the necessity of changing how they prepare and dynamize classes towards using teaching methods that give the students an active role to learn, investigate, reflect, etc. [

11]. That is why, according to Moran et al. [

12], teachers cannot be replaced by ICTs, even though technologies have surely changed their job description because the information is now available everywhere (in books, the internet, videos, streaming services, and so on). They continue to have an important role, but now as mediators of the students’ learning process by creating problems and asking questions, guiding the students during research, and inciting reflection and debates about the subjects [

13], or by applying student-centered learning models as opposed to traditional ones.

Student-centered learning is nowadays proclaimed by scientific literature and politics as the most suitable method of teaching and learning to transition to a paradigm of knowledge construction from knowledge transmission [

14]. To achieve this, classes must be planned to implement student-driven learning activities, balancing theory (literacy, numeracy, sciences, etc.) and practice (experimenting, researching, discussing, talking about how students perceive the world, etc.), both contextualized in students’ daily life, customs, and culture. The implementation of student-centered learning processes is the way to contribute to students’ learning to know, to be, to live together, to do [

15], to transform oneself and society [

16], and to give and share [

14].

However, learning models in higher education still tend to be traditional, or teacher/curriculum centered [

3,

12,

17], which leaves little room for alternative approaches to both teaching and learning [

14]. ICTs are mainly used as administrative tools (for managing registrations, payments, grades) or as a communication tool between each student and each teacher. Hence, ICTs are not yet fully embedded in formal education practices [

3] and have not been enough to transform education [

4]. For Gesser [

18], a stiff curriculum structure, teachers’ resistance to change and lack of practice using ICTs, students’ low capacity to stay focused, and the lack of financial support from higher institutions are some of the factors that could help explain the resistance to innovate teaching and learning practices enabled by ICTs. Moran [

19] claims that higher education institutions are conservative and guided by traditional cultures that resist change, hence their lingering in traditional learning models. Unlike Gesser [

18], this author says teachers know their pedagogical practices must change but do not know how, so they resist while simultaneously making smaller concessions, for example, by using universities’ platforms to communicate with and grade students (Moodle platform in Portugal). Moran [

19] enhances the fact that aside from training in the use of ICTs, teachers also need training to implement ICT-enabled pedagogical practices and student-centered learning models. And, he adds, some institutions enhance the teachers’ resistance by demanding changes without providing the necessary support.

Changes are slowly happening, even though current educational reforms tend to focus on setting standards and assessment procedures instead of pursuing true innovation in education [

20], defined as the implementation of student-centered learning experiences where students may use creativity and collaborative learning to find solutions for the problems given to them, and teachers are facilitators of learning and not mere distributors of information [

19,

20].

Following Ellison’s perspective [

21], we distinguish between ICT-enabled educational innovation in two different categories: administrative when focused on the institution’s organization and administration processes, and instructional, which occurs when learning models (pedagogical practices, achievement assessment, and curriculum approaches) change by using ICTs. To provide students with rich learning environments, boost their motivation to learn, increase academic achievement, and prepare them for the 21st century, it is fundamental to mobilize ICTs in learning processes [

22] as new ways to use and create information and knowledge and not just to replicate traditional learning practices [

23]. Technologies can be instrumental to approaching the curriculum in a more interesting way, for example, by creating the possibility to bring real-life problems into the classroom, to provide tools to enhance learning, to review and test knowledge more often, to give faster feedback to students about their performance, to incentivize reflection and debates on their ideas, and also to create global communities among all students, teachers, and outsiders, thus expanding the learning experiences [

24].

However, it all depends on how teachers mobilize technology in the classroom [

5,

18,

19]. While some use ICTs to teach the standard curriculum through traditional learning models [

25], others are using ICTs within a constructivist approach that see students as active agents (setting the goals and planning and monitoring their learning process), working collaboratively with their peers and engaging to find solutions to real or real-based problems by mobilizing different disciplines [

24]. This author found evidence that teachers are increasing use of student-centered learning models with ICT-enabled pedagogical practices. Nevertheless, implementation of ICT-enabled learning models, such as e-learning, m-learning, digital models, or artificial intelligence and simulators, is still challenging in higher education because of social, cultural, organizational, [

4] and, we might add, funding variables.

Many authors created models and classifications for ICT-enabled innovation for learning. Among the most interesting are the three degrees of innovation of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) [

26]: (i) incremental, as in minor changes in services/products; (ii) radical, when it introduces new services or new practices related to services/products; (iii) or systemic, when new dimensions are introduced in the overall performance. Law et al. [

27] developed six dimensions of analysis following an ecological study about emergent ICT-enabled pedagogical innovations: (i) learning objectives, to analyze which curriculum goals align with 21st-century skills; (ii) teachers and (iii) students’ role in differentiating between emerging and traditional pedagogical practices; (iv) level to which ICTs are used; (v) connectedness, or level of involvement of outsiders (experts and parents, for example) in teaching and learning processes; and (vi) a multiplicity of learning outcomes. Each dimension is then evaluated within the scale of innovativeness between the levels of traditional (traditional in all six dimensions, or teacher-centered, where ICTs are used to replicate traditional learning models), emergent (midway), and most innovative classrooms (innovative practices in all six dimensions, or student-centered).

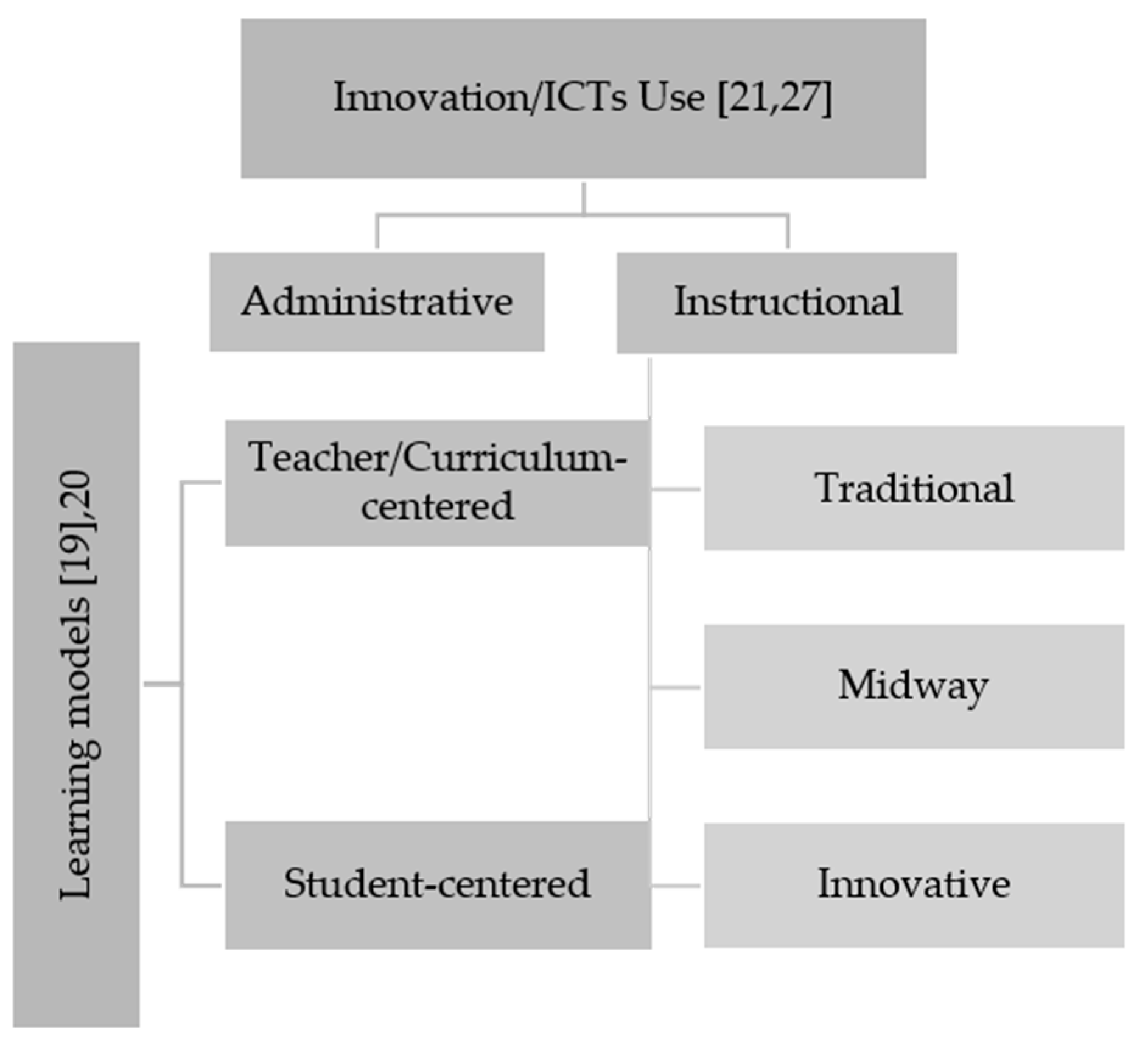

Our model of analysis (

Figure 1) was created from the theories and discoveries by Moran [

19], Fullan [

20], Ellison [

21], and Law et al. [

27] to identify the learning methods and the role technologies play in pedagogical practices before and after COVID-19 in Portuguese veterinarian programs, how teachers and students adapted to changes, what the outcomes were, and what is to be expected in the future.

Learning models can be teacher/curriculum centered when characterized by expositive and inquisitive pedagogical practices, an active role from teachers who transmit information and evaluate the students about the amount of information learned and passive roles from students; or student-centered when teachers assume the role of mediators of the students’ learning process and students take responsibility for setting their own objectives, study methods, and results [

19,

20]. Innovation in education through ICTs can be administrative when used as a tool to help the institution and class organization or instructional when teachers mobilize ICTs in their pedagogical practices [

21]. The use of ICTs in pedagogical practices then divides into (i) traditional when teachers only use technologies to replicate teacher-/curriculum-centered learning models, (ii) midway when some dimensions show signs of innovativeness; (iii) or innovative when objectives, students’ and teachers’ roles, use of ICTs, the involvement of outsiders, and the outcomes are defined as part of the student-centered learning models [

27].

2. Materials and Methods

This research about the learning models and the use of ICTs in veterinary programs in Portugal was possible because a team of researchers from Centre for Research and Studies in Sociology of the University Institute of Lisbon (CIES – Iscte-IUL) started a study about the profession of the veterinarian in the national context in July 2019 with three main objectives: (i) Make a complete diagnostic about the profession of the veterinarian in Portugal (formal education and training, access to the professional activities, employment, representation, the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on formal education and professional activities, and professionals’ representations about the previous dimensions), (ii) build a “veterinarian census” to characterize the population of veterinarians working in the national territory in all dimensions, and (iii) provide recommendations for the elaboration of a strategic plan for the Professional Order. For this article, we focused on the data collected from interviews applied to teachers and students of the Portuguese higher education institutions with veterinarian courses.

There are currently seven veterinary programs in the national context: four in public higher education institutions and three in private institutions. Two of the private options were not included in the study. One opened in 2020 after the conclusion of fieldwork (July 2020). The other never answered the invitations to participate in the study despite several efforts and attempts made by the team of researchers and the members of the Professional Order of Veterinarians. Therefore, this study only includes five veterinary programs from four public institutions and one private institution. The oldest opened in 1830 in Lisbon, in an institution that is nowadays known as the Faculty of Veterinarian Medicine of the University of Lisbon (UL); this is currently the institution that graduates the most veterinarians every year. The other public programs started in 1975 in Évora (in the south) in the Escola de Ciências e Tecnologias from the University of Évora (UE), in 1987 in Vila Real (in the north) in the School of Agrarian and Veterinary Sciences from the University of Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro (UTAD), and in 1994 in Porto (also in the north) with the creation of the Institute of Biomedical Sciences Abel Salazar from the University of Porto (UP), which is characterized by developing work within the paradigm of One Health. All these are public institutions that changed their statute, structure, and organization throughout the years but kept their veterinary programs active from before the aforementioned years. The programs in the private institutions opened much later. The first and only one that was included in this study opened in 1998 in Coimbra (in the center of Portugal) in the School University Vasco da Gama (SUVG). A second program began in the same year in the Universidade Lusófona de Humanidades e Tecnologias in Lisbon and a third opened in CESPU—Cooperativa de Ensino Superior Politécnico e Universitário—in Porto (these are the two programs not included in the study for the reasons explained above). From this point on, we will use the acronyms to designate the programs/institutions to facilitate the writing and reading processes.

The study was conducted in five higher education institutions (UL, UE, UP, UTAD, and SUVG), in the Academic Federation of Veterinary Medicine (which represents students enrolled in all veterinary programs in Portugal) and the Professional Order of Veterinarians. Data was collected through interviews and documents.

First, we applied 20 interviews: (i) individual interviews with three teachers and the director from the five veterinary programs indicated above; (ii) group interviews, one with the four leaders of the Academic Federation of Veterinary Medicine, and one with six members from the Professional Order of Veterinarians (scheduled to discuss specifically the impact of COVID-19 on formal education, training, and the profession itself). With the exception of the interview that focused on the impact of COVID-19, all interviews followed a script built by the CIES—ISCTE-IUL team in the context of the study about the veterinarian profession in Portugal and were applied by three members of that same team. The script included several questions organized in four different dimensions: (i) formal education and training, (ii) access to professional activities, (iii) employment, and (iv) representations of the profession. Data was collected by applying semi-structured individual and group interviews to ask about the previous specific dimensions and provide a certain level of normality to allow for the comparison between actors and institutions [

28] and, simultaneously, guarantee the interviewees the time to reflect on the subjects and answer the questions freely [

29].

For the present article we only used interviewee responses about formal education and training, more specifically about the curricular plans, classes, teaching and learning methodologies, how they organize programs (student enrollment, tuition payment, evaluation process), and the impacts of COVID-19 when available.

Some interviews were conducted face-to-face before the COVID-19 outbreak and do not have data about the changes the pandemic introduced. This is the case with the interviews from the director and two teachers from UL, and all four interviews from UE and SUVG (

Table 1).

As indicated previously, we also collected data from specific documents: (i) the evaluation reports from the Portuguese agency that accredited the six higher education programs in Portugal, including ULHT, to provide an analysis of the curricular plans of each veterinary program; (ii) and the Evaluation Report of Curricular Plans of six veterinary programs written by the Academic Federation of Veterinarian Medicine in the year 2018–2019 based on the results from a questionnaire applied to a total of 1214 students (corresponding to 45% of the total of 2689 students enrolled in veterinary programs) to collect data about the perceptions of the students on the six veterinary programs (ULHT included as well). These reports were used as qualitative sources of information in this study to complement the main results and were not subjected to the same coding and categorization process as the discourses collected through interviews.

2.1. The Coding and Categorization Processes of Interviewees’ Speeches

Considering this set of data, we used a qualitative approach to study the learning models and the use of ICTs in veterinary programs.

Content analysis was used as an adequate qualitative technique to analyze all speeches produced by the interviewees. This process was organized according to the dimensions drawn from the questions presented at the beginning of the article and the model of analysis presented in the previous section: (i) learning models of veterinary programs, (ii) use of ICTs, (iii) changes caused by the pandemic outbreak, and (iv) teachers and students’ perceptions about the changes and future outcomes. In the first dimension, learning models, we searched for references of teacher-/curriculum-centered and of student-centered practices. Then we analyzed how institutions and teachers use ICTs to identify if the use is just administrative or if there is an instructional use of ICTs and what kind (traditional, midway, or innovative). In the third dimension we identified all changes that were indicated by the actors, and their discourses point to two different categories: changes in lectures and changes in hands-on sessions. In the last dimension we listed the actors’ perceptions about the changes and outcomes for the future regarding students’ education, curricular plans, and teaching and learning practices.

Throughout this process we used one analytical grid to efficiently operationalize the comparison between programs/institutions and actors (the analytical grid was summarized in the tables presented in the Results section).

2.2. COVID-19 in Portugal

The COVID-19 pandemic and the perceived impact of the confinement measures on education motivated us to write this article. Not only was the process of collecting data within the project about the veterinarian profession in Portugal affected (rescheduling interviews, adapting the scripts and researchers instructions to a digital environment, etc.), but the interviewees’ speeches also started to include reflections about the significant changes in teaching and learning brought on by the mandatory confinement. Throughout that project, professionals, teachers, and students stated that veterinary programs are very dynamic and intense because of hands-on sessions, which is the opposite of what students usually say about their higher education programs. Therefore, we wanted to know more about the veterinary programs’ curricular plans and teaching and learning practices, and about the changes imposed by the pandemic outbreak.

The pandemic started officially in Portugal on 2 March, 2020, the day when the first two positive cases were confirmed on national territory. The government responded with several containment measures, such as canceling sports and cultural events and locations, for example, while asking the population to remain home and take the necessary precautions. But due to the exponential increase of COVID-19-positive cases, the government declared a State of Emergency on 18 March, 2020, and with it mandatory confinement and the lockup of all public and private organizations and businesses. However, the Portuguese population, organizations, and businesses started to implement their own measures before the declaration of the State of Emergency. Higher education institutions, for example, implemented contingency plans that were adjusted regularly and eventually canceled all on-campus classes and national and international field trips. Iscte contingency plan started on 10 March, 2020, three days before the trip to Vila Real to apply the interviews in UTAD that had to be rescheduled to June. From mid-March through the end of the school year, the entire Portuguese education system transitioned to digital lectures.

3. Results

Before presenting the results, it is important to show that the curricular plans of the six Portuguese veterinary programs are very similar because all institutions follow the guidelines from the European Association of Establishments for Veterinary Education (EAEVE) created in 1988 with the following mission: “to evaluate, promote and further develop the quality and standard of veterinary medical establishments and their teaching within, but not limited to, the member states of the European Union” [

30]. In order to be accredited, each institution must prove that the veterinary program answers the standards defined by EAEVE for several different items organized in 10 dimensions: (i) objectives, organization, and quality and assessment policy; (ii) finances; (iii) curriculum; (iv) facilities and equipment; (v) animal resources and teaching material of animal origin; (vi) learning resources; (vii) student admission, progression, and welfare; (viii) student assessment; (ix) academic and support staff; and (x) research programs and continuing and postgraduate education. Focusing on the “curricular” dimension, all programs must be integrated masters (with a minimum of 360 ECTS (European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System) credits) and have a curricular plan based on lectures and seminars about (i) basic subjects (such as chemistry and biology, for example), (ii) specific veterinary subjects (basic sciences, clinical sciences, animal production, food safety and quality, public health, and One Health Concept), and (iii) practice sessions such as supervised self-learning, laboratory and desk-based work, non-clinical animal work, clinical animal work, and an internship (all of which we address in this paper as hands-on sessions, as designated by teachers and students).

The curricular plans of the six veterinary programs are very similar (see

Table 2) and built from information collected from the six institutions’ websites [

31]; however, in the national context, UL has the only accredited program by the EAEVE, and the one from UTAD has been approved and is still in the process of accreditation. Among other reasons, directors and teachers from UL and UTAD claim that the diversity of facilities and equipment, multiple animal resources and teaching material of animal origin, and diverse learning resources are a major part of their institutions’ accreditation and approval.

But all the other three interviewed directors (from UE, UP, and SUVG) stated they would also like to have their programs accredited, and that is why all curricular plans are very similar (CU and ECTS values are alike).

There are minor differences between the six veterinary programs concerning the focus that some areas of veterinarian medicine receive (for example, food security is more relevant in SUVG and animal production in UE) or the number of ECTS (European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System) credits assigned to practice sessions and internships. The CU and ECTS numbers in

Table 2 clearly show that all curricular plans focus the area of the clinic (whether small or big animals) and include a considerable amount of ECTS credits for hands-on sessions, as requested by EAEVE guidelines. This is because veterinarian medicine, especially in the area of the clinic, is developing fast in terms of animals’ diagnosis and treatment as a response to societal changes such as the process of animal humanization, which implies higher demands from and expectations for veterinarians and a higher number of students looking forward to getting an education in that specific area. The members of the Professional Order of Veterinarians show signs of concern about what they say is the excessive number of veterinary programs in Portugal, especially compared to other European countries and considering that only two of the programs were accredited/approved by EAVE, raising doubts about the quality of the other programs.

3.1. Learning Models in Veterinary Programs

According to the five directors and 15 teachers that were interviewed, their aim is to train new autonomous veterinarians capable of handling different types of animals, making the correct diagnosis and setting the right treatments, and, simultaneously, make professionals aware that they need to keep updated with all the new developments of the diverse areas of veterinarian medicine. The perceptions from the members of the Professional Order of Veterinarians and the leaders of the Academic Federation about what future veterinarians must be are consistent with the profile defined by the directors and teachers.

To achieve those objectives, teachers gave examples of pedagogical practices (see

Table 3) such as using real-life cases for students to diagnose and define treatments or train intervention techniques (Teachers A, B, C, M, O, P, Q), taking field trips to train with different areas and animals (Director 1, Teachers E, H, I, J, M, N, O, P, Q), and service in hospitals and other facilities on and off campus (Teachers B, F, L, M, P, O, P, Q). Some teachers also consider it important to train the students in soft skills such as, hospital and/or clinic management (Teacher L), communication tools for talking to clients (Teachers B, L), ethical issues (Teachers E), searching and validating information (Teacher F), and thinking about veterinarian medicine as a multidisciplinary area that is constantly developing (Director 3, Teachers C, H, O).

Hands-on sessions are considered important by all teachers because “it is necessary to teach students how to think and to keep up to date with constant developments in procedures, diagnosis, treatment, etc.” (teacher A). All these examples are consistent with active roles from students and mediating roles from teachers who mix lectures with hands-on sessions and guide students in their learning processes. It is important to mention that some teachers claim they must fight students’ tendency to search for information and accepting “it as the truth without validating; they look, find, and use it and that is it” (teacher F), and to “memorize [because] that is the opposite of what a veterinarian must do. He/she must use different sets of knowledge to diagnose and treat animals” (teacher B).

However, we must also consider that in the first two years of veterinary programs, according to all interviewed teachers and students, curricular units focus on general basic and veterinary--specific basic subjects. The report about the curricular plans elaborated by the Academic Federation shows that students claim that some classes are too expositive, and the curriculum is not up to date with all developments in veterinarian medicine. The percentage of students that make this complaint is higher in the institutions where the average age of the faculty is higher, such as in UL, the oldest institution in the national territory. Interviewed students from the Academic Federation confirm that this is mainly a problem of the first and second years, saying that “in the last few years there has been more innovation and communication to students about new developments, unlike what happens in the first two years” (student 3). Teachers from the five institutions claim that in the first two years the programs tend to focus on general basic and veterinary-specific subjects because students must gather knowledge that they will have to use later during hands-on sessions and then as veterinarians. Teacher I, for example, says that veterinary programs emphasize “disciplines based on knowledge from the first years.”

3.2. Use of ICTs

Beginning with the use of ICTs incentivized by the five higher education institutions, we observed that all of them have a platform organization to manage inscriptions, payments, and formal requests for documents or other requests from students, etc.; and to manage disciplines where teachers share documents, articles, books, and work requests; insert grades; and respond to students when they ask for guidance (see

Table 4). As for learning models and ICT-enabled learning practices in the five institutions, there is no general policy and teachers have full autonomy to decide how to conduct their lectures and hands-on-sessions.

ICTS are usually used to replicate traditional learning models because teachers use computers and specific programs such as PowerPoint and Prezi as visual aids while conveying the information. The only other sign of ICTs being used as part of pedagogical practices came from Teacher C from UL. This teacher and several of her colleagues use the platform provided by the Portuguese government for all public education institutions, the Moodle platform, to administer the exams (true-or-false question exams).

3.3. Changes Caused by COVID-19

UL was the only institution that had a version of the Moodle platform adapted for e-learning before the outbreak, and thus was fully prepared to transition to online lectures when the government decided to implement the mandatory confinement due to the COVID-19 outbreak. The other four only had versions to manage the program’s organization and to serve as communication tools. Therefore they had to expand their Moodle platforms before they could begin distance education. All interviewed teachers and students said that all lectures were able to proceed with almost no changes, and all hands-on sessions such as service in hospitals and other facilities on campus, field trips, internships, etc., were canceled (see

Table 5).

In the curricular units, however, we found that some teachers were able to use ICTs in online lectures to maintain some moments that could be considered close to hands-on sessions. For example, Teachers C (imageology) and M (necropsies) provided images from real cases that students had to analyze, diagnose, and define treatment possibilities/determine the cause of death, thus training those skills. Teacher M stated that she and a colleague had no extra work transitioning their lectures to an online platform because they had been building a database of images, exam results, surgical procedures, and other items to be used as teaching and learning practice to train students to think, to make decisions, and to be autonomous.

However, most teachers say that it is more difficult to train students in clinical and surgical procedures at a distance. Even Teacher M, who was able to show her students all the steps to several surgical procedures through images that she had collected throughout the years, said that to “discuss real cases, how to talk to clients is one thing, but through online lectures, there is no way to substitute the training of students in the skill of using a real scalpel.” Teacher L considers that teaching surgical skills online is “surreal” and added that she and her colleagues from UTAD are already working on a set of hands-on sessions to replace the ones that were canceled in order to allow students to train the necessary skills as soon as the institution reopens.

Teachers H, J, and L also consider that real-life interaction between teachers and students is crucial to showing the latter the right postures and maneuvers during technical procedures, how to behave near animals and clients, and to discuss with them the subjects, skills, and difficulties. They consider face-to-face interaction a crucial part of the students’ training. All teachers consider that students’ learning and training will not be complete unless they are given a chance to go back to real hands-on sessions with their teachers and with outside partners.

During the group interview with the leaders of the Academic Federation, we also asked students about the difficulties associated with attending online lectures. According to their own perceptions and those of the students they had asked about the access to online lectures, the leaders of the Academic Federation said they had had a few reports about a few students that could not attend education at a distance because they had no laptop and/or internet connection. However, this was not a problem for most students. Their perceptions about online lectures is that some teachers with whom they had hands-on sessions made huge efforts to minimize the losses from canceling practical classes and internships, but they feel it was not enough because they could not train the procedures with their own hands. Surprisingly, students claim that online lectures may continue in curricular units about general and veterinary-specific basic subjects because they had no distractions (no friends, no going to cafés, no conversations, etc.) and because it saved them time (no need to commute to campus and back home) that they used to study. This was also mentioned by the members of the Professional Order of Veterinarians, and one member added that online lectures that could be recorded and used as another instrument for study was a positive thing.

3.4. Teachers and Students’ Perceptions about the Changes and Future Outcomes

Finally, let us look at the actors’ concerns and hopes for the future following the changes imposed in veterinary education by COVID-19 (see

Table 6).

For teachers and students, the cancellation of all hands-on sessions represents major irreversible losses in the students’ training and some defined it as a catastrophe (Teachers L, M, N) for students enrolled in their final year because they were not able to complete their internships. The common feeling among teachers can be summarized in the following reflection from Teacher H: “After this, I hope things change because of the needs of students and teachers and the developments within the various areas and disciplines and not because of the pandemic. The veterinary programs are dynamic and must be, and are, reviewed regularly, but not because of a fortuitous thing like the coronavirus.”

Most teachers look at ICTs as something to be explored in the future to keep regular communication with students, to be used as e-learning in some curricular units (about general and veterinary-specific basic subjects), and as another possible studying tool for students (recorded audio or video files from online lectures). Only Director 4 and Teacher A clearly said that ICTs are worth exploring as a way to enable student-centered practices if, for example, video and audio files and/or even computer-assisted learning to simulate medical and biological processes in animals could be used as a way to show students what and how to do the several clinical and surgical procedures.

Students look at the pandemic and online classes as an opportunity to review and modernize the curriculum of some curricular units and to continue online lectures in curricular units about general and veterinary-specific basic subjects, thus reducing their schedules (with less time spent commuting and on campus) and increasing the time available to study. One student added that COVID-19 also increased the voices of students not only in class but also in institutions. However, students are worried about the cancellation of hands-on sessions and claim that the real impact of the changes introduced in veterinary programs because of the pandemic outbreak on their training remains to be seen in the future.

As for the members of the Professional Order of Veterinarians, the pandemic outbreak could be an opportunity to invest in online lectures in the future not only for students enrolled in veterinary programs but also for professionals as a way to incentivize an increase in veterinarian qualifications and knowledge, even among professionals who work and/or live at a great distance from higher education institutions with veterinary programs, and to implement new teaching practices. This last perception was also mentioned by Director 4, who considers this scenario caused by the pandemic outbreak an “opportunity to teach several disciplines using student-centered and ICT-enabled learning methods as encouraged by the Bologna Declaration.”

4. Discussion

The analysis of the veterinary programs’ curricular plans shows how similar they are. All six institutions follow EAEVE guidelines to maintain or achieve accreditation, which explains the resemblance in CU and ECTS credit distribution. They have more CUs and ECTS credits assigned to the area of the clinic because veterinarians worldwide, EAEVE included, are responding to societal changes such as the process of animals’ humanization. This new paradigm of considering pets as part of the family and all animals as sentient beings is causing rapid developments in veterinarian medicine and also appealing to a higher number of students drawn to the desire to help and take care of animals.

Considering the main objectives of the five institutions and their professionals—to train autonomous, resilient, and pro-active veterinarians fully capacitated to identify and solve problems—and the pedagogical practices described by most of the interviewed teachers that highlight how should students have an active role in their learning process while being guided by the teachers, we can consider that veterinary programs include some of the characteristics of student-centered learning models. There is a gap between the first two years of veterinary programs, when the curriculum is not always up to date with the developments in veterinarian medicine and teachers tend to implement traditional teaching and learning practices because they focus on transmitting their knowledge to students; and the last three years when teachers and students seem to be engaged in different teaching and learning practices: solving real-life problems, discussions, researching, and experimenting in different veterinary subjects and with several different animals. This could be explained by the fact that in the first years, according to teachers and students, veterinary programs focus on general basic subjects (such as chemistry, deontology, and biology) and veterinary-specific basic subjects (for example, animal anatomy and epidemiology). This shows that teaching and learning practices in veterinary programs [

17,

19] go from mainly traditional in the first years to more student-centered in the last three when hands-on sessions generally begin to be a part of students’ daily life on and off campus. We must also consider the signs of frustration among many of the interviewed teachers regarding students’ skills and willingness to engage in student-centered practices: not knowing how to search and validate information and focusing on memorization instead of building knowledge are some examples. This makes us think that student-centered learning models require both teachers and students to change their practices, which makes OECD guidelines for basic and secondary education [

3] crucial. Students will become more autonomous and the masters of their learning processes if they acquire the right skills during basic and secondary education.

Looking at the five institutions included in this study, we found that the use of ICTs is, at an institutional level, incentivized as an administrative and communication tool as defined by Ellison [

21]. There are no signs that these institutions ask their teachers to increase the use of ICTs as part of their pedagogical practices besides the training students must have with specific equipment for the practice of the veterinary profession. The analysis of the instructional use of ICTs in veterinary programs confirms the results of the studies mentioned before [

5,

9,

26,

32]: ICT-enabled learning models remained incipient before the COVID-19 outbreak. Of course, we must also mention that in veterinary programs, students learn how to use equipment and technologies (such as x-rays and magnetic resonance imaging, for example) as part of their training, and in these cases, specific technologies are used by teachers as part of the pedagogical practices. But these specific technologies are usually part of teaching and learning practices in hands-on sessions. During lectures, ICTs were not used to implement innovative or even midway instructional practices [

27].

The COVID-19 outbreak showed that only one institution and one interviewed teacher amongst the 15 that were interviewed were ready to transition to online lectures. All others had to adapt after the outbreak happened. The fact that one institution was already equipped with a platform that allowed lectures online but that no teachers that we know of used that instrument to dynamize innovative teaching and learning practices, even to solve the problem of having too many students to divide between all hands-on sessions, shows that having the right equipment and instruments available is not enough to implement innovative teaching and learning practices.

Results show that curricular units about general basic and veterinary-specific basic subjects are more easily transformed in online lectures and that some subjects are also possible to organize in ways that can provide students with some skills training: solving real-life problems and visualizing technical procedures are examples. However, all teachers and students found it difficult to teach and to learn about surgical procedures because they had no way to experiment with how to apply the clinical or surgical procedures with their own hands. ICTs that were used were considered important in the context of the pandemic, but teachers and students hope to get back to real hands-on sessions. This could be a result of the limited available ICTs—the internet, platforms, image databases, and audio and video files.

The main negative perception about the changes imposed by COVID-19 in veterinary programs from all actors—teachers, students, and the members of the Professional Order—concerns what they designated as major losses in the students’ education because of the cancellation of all practice sessions and internships. Even teachers that were able to somewhat replace parts of the practice sessions during online lectures say that it is impossible to teach and to train the right postures and procedures, and the correct use of instruments to apply in clinical and surgical procedures through online lectures. We might consider that the incipient use of ICTs before the outbreak and the lack of modern technologies in institutions (not considering veterinary-specific equipment) certainly did not help teachers to find innovative solutions to continue hands-on sessions online with minor changes, such as, for example, remote shadowing during services (clinical and surgical) that remained active in campus facilities. It would be interesting to consider the use of more advanced ICTs in veterinary programs such as virtual environments, 3D images, artificial intelligence, automation, and robotics, for example, that could provide students the possibility to train all kinds of technical procedures in several different animals. This could also be a way to guarantee a complete set of skills in diverse animals to all students across national territory. Not only would institutions stop being dependent on the animals, partners, and equipment available to train their students, but the recent ethical issues surrounding animal welfare and animal rights would also be solved. This is a vision of ICT use that is far from most interviewed teachers and students who look at ICTs mainly as communication tools.

However, this pandemic is also seen by the actors as an opportunity to improve. Most of them agree that curricular units about general and veterinary-specific basic subjects could continue as e-learning. Students feel this could be a way to keep them focused on lectures and save them time to study, both teachers and students claimed that it increased the communication between them, and teachers and members of the Professional Order think online lectures can be used to help students study. As for curricular plans, only the students think of distance education as an opportunity to review and modernize the curricular plans. Only a few teachers said that curricular plans must be reviewed regularly because of the rapid developments in the area and to respond to societal changes, refusing the idea of making changes just because of the pandemic outbreak. What some teachers and the members of the Professional Order of Veterinarians see is the opportunity to explore new teaching and learning practices enabled by ICTs such as digital files and computer-assisted learning to implement innovative learning models.

5. Conclusions

Before COVID-19, all veterinary programs were dynamized through learning and teaching practices from traditional learning models, or teacher-/curriculum-centered, in the first two years and closer to student-centered models in the last three, which concentrate most of the hands-on sessions (practice sessions and internships). Veterinary programs, especially during the last years, are characterized by the regular use of teaching and learning practices that place students in the center of the learning process and give teachers the role of mediators. Specific veterinary technologies are used during hands-on sessions, but the use of ICTs in lectures mainly replicates traditional teaching practices, and the actors’ speeches do not contain references to innovative practices or to the use of ICTs as enablers of innovative teaching and learning models during lectures.

So, how did teachers and students of veterinary programs adapt to distance education? The answer is both well and not so well. According to the actors, the transition of lectures, particularly in curricular units about general and veterinary-specific basic subjects, was smooth and even accompanied by some positive signs such as, for example, better communication between students and teachers and an increase in the students’ focus and participation during lectures. We can consider that it was a good experience that most believe should continue in the future. It would also be a way to provide extra education and knowledge refreshment and updates for active veterinarians and increase the possibility for them to access those programs, especially those who live and/or work far from any of the current seven institutions.

But there is also a negative answer to that question. All interviewed actors mention that the cancellation of all hands-on sessions (practical sessions and internships) due to the pandemic outbreak represents major losses for the students who are enrolled in veterinary programs. As we observed, some teachers found ways to replace part of some hands-on sessions because some teaching and learning practices are easily dynamized through online lectures (solving real-life problems, researching, and validating information, for example). But the real problem came when it was time to allow the students to experiment and to train in clinical and surgical procedures: how to use the instruments correctly, how to deal with animals, how to communicate with animals’ owners, and how to readapt the procedures if necessary. ICTs such as learning to simulate medical and biological processes in animals, virtual reality, and even simpler equipment such as video cameras shadowing teachers while conducting real-life procedures in animals could have been helpful but were not considered. The incipient use of ICTs and the lack of more advanced equipment were certainly barriers.

Teachers, students, and the members of the Professional Order were alerted to the need to increase investment in innovative teaching and learning practices in the near future, and some teachers manifested a wish to further explore the use of ICTs to enable innovation in veterinary education.