Heterogeneity versus Homogeneity in Schools: A Study of the Educational Value of Classroom Interaction

Abstract

1. Introduction

“the influence exercised by adult generations on those that are not ready for social life. Its object is to arouse and to develop in the child a certain number of physical, intellectual, and moral states that are demanded of him by the political society as a whole and by the special milieu for which he is specifically destined. To the egotistic and asocial being that has just been born, [society] must as rapidly as possible add another capable of leading a moral and social life”.[9] (p. 148)

“The right to education is a fundamental human right. Yet, many European countries still deny thousands of children, including children with disabilities, Roma children and refugee or migrant children, equal access to it by keeping them in segregated schools. This is a violation of children’s human rights with far-reaching negative consequences for our societies. Member states have an obligation to secure the right of every child to quality education without discrimination”.[15]

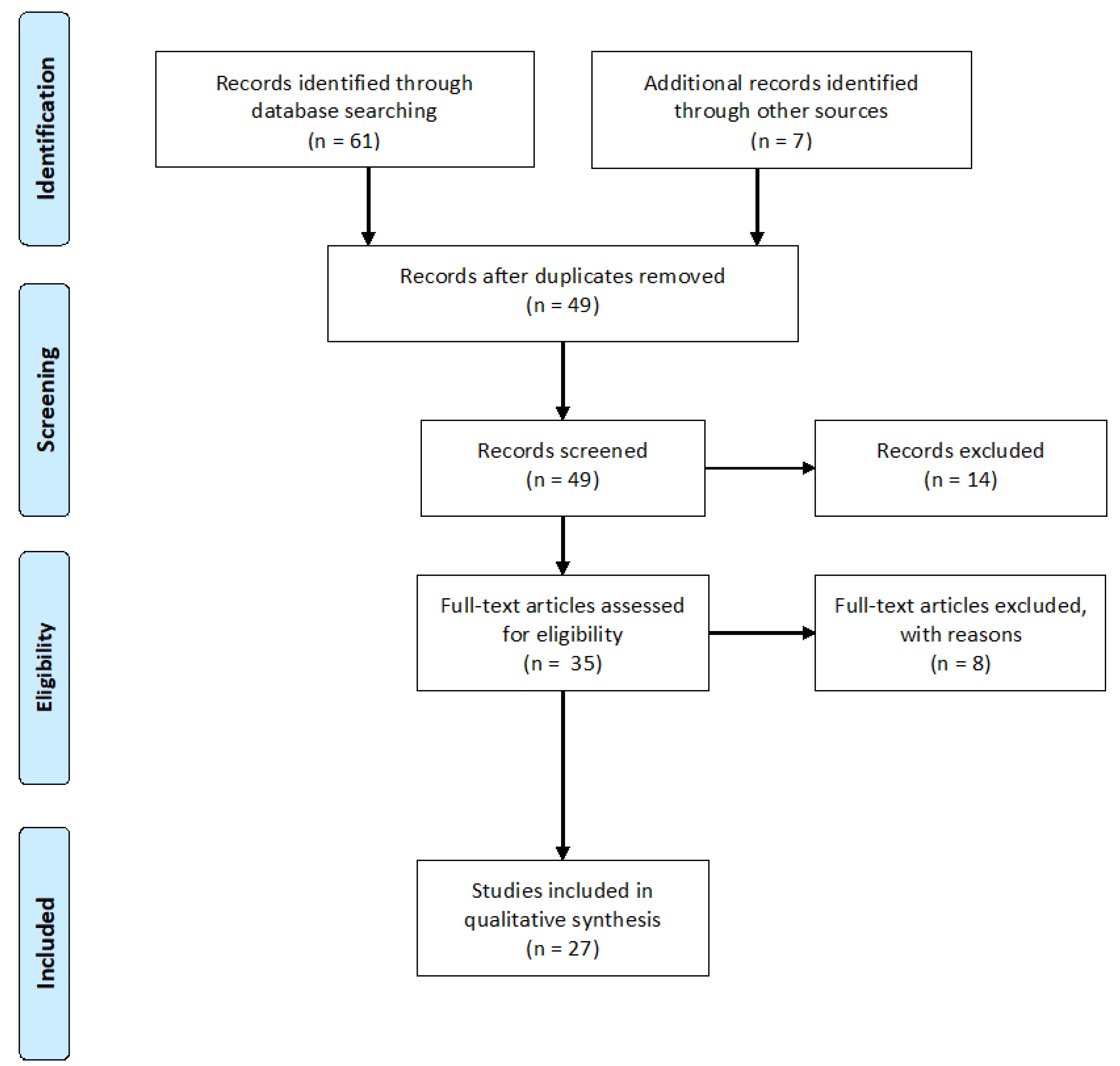

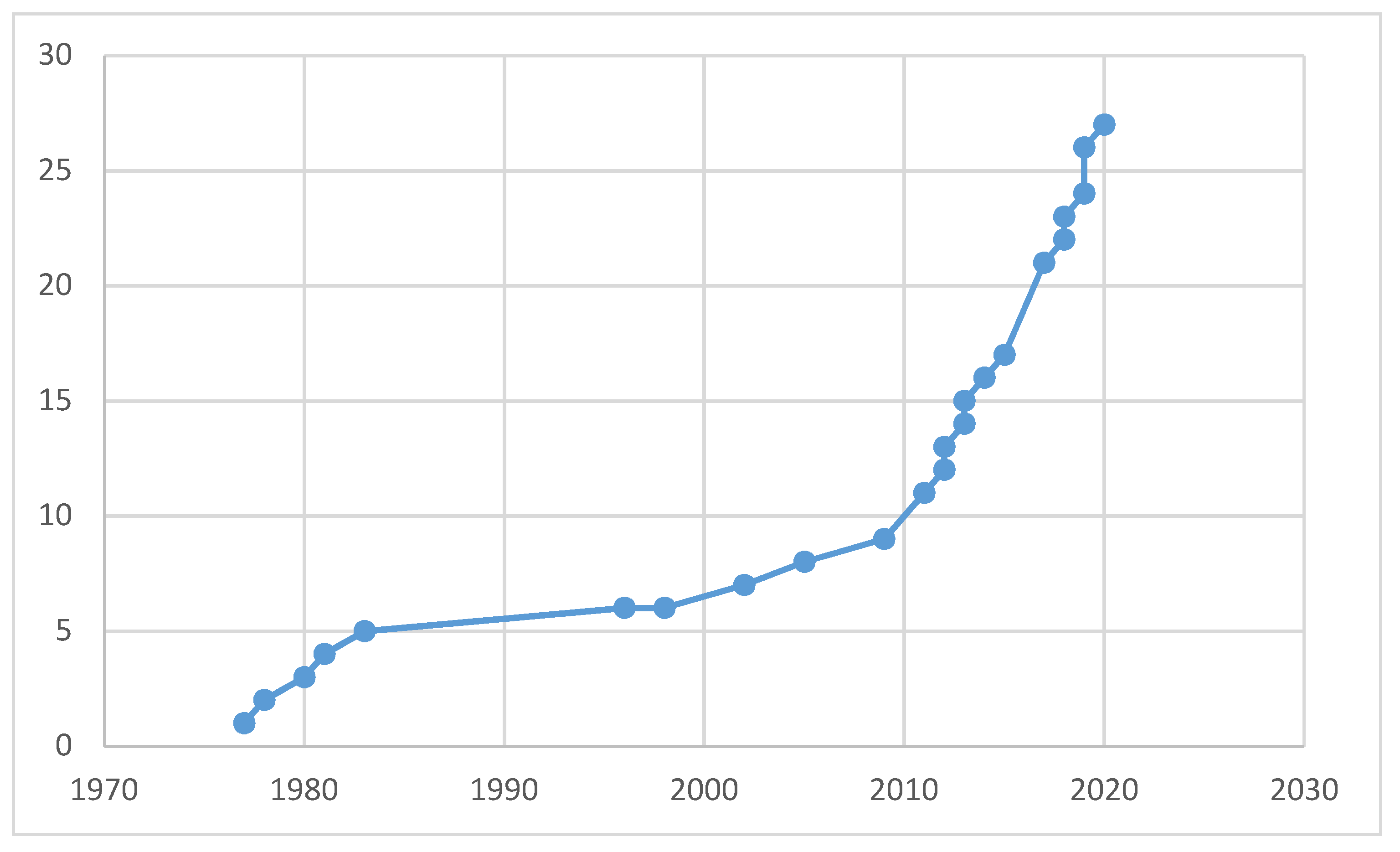

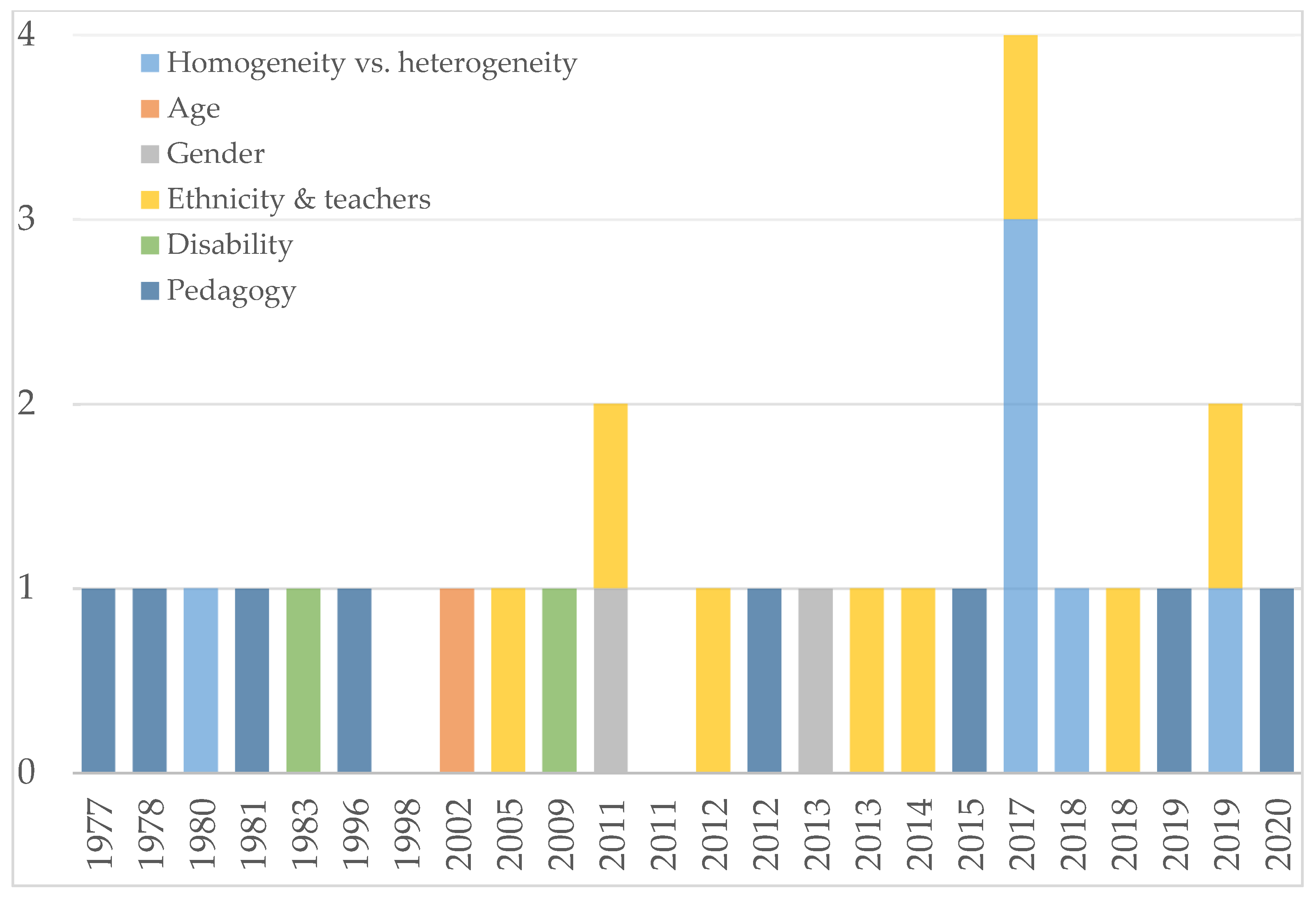

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Pedagogy

3.2. Ethnicity and Teachers

“teachers’ intended goal in class discussions is to foster interculturality, inclusion and class participation of immigrant and minority children, these practices, as realized in actual student–teacher interactions, may have the unintended, paradoxical consequence of further marking Moroccan immigrant children’s as ‘Other’, and of symbolically upholding ideals of a homogeneous imagined national community (…) of which the immigrant children in the class cannot be part. teachers, inadvertently and ironically, take part in excluding immigrant children from belonging to the national collectivity, by engaging in practices of distinction, authentication, and authorization through everyday linguistic and interactional practices, such as deixis, appellation, and forms of class participation”.[36] (p. 491)

‘teachers take an active role in promoting positive and healthy relationships at school, they will be promoting children’s development and fostering school performance. [… Therefore] teachers should adopt a cooperative mode of teaching, act as social referents for their students’ behaviour and avoid negative feedback to aggressive-rejected children to prevent further rejection’.[39] (p. 31)

‘cross-race friendships have been found to be a significant factor in the reduction of prejudice (…) Children with friends from different ethnic groups recognize that variation exists across groups as well as within groups, thus reducing outgroup homogeneity attributions. Cross-race friendships also increase sensitivity to the negative impact of discrimination and prejudice’.[40] (p. 683)

3.3. Homogeneity versus Heterogeneity

‘we see that there is no evidence for high-ability groups that the heterogeneity in the group affects students. For low-ability groups, on the other hand, we find that low-ability students are negatively affected by more heterogeneity in the group, while again we find no peer effects for high-ability students. In summary, we find peer effects for low-ability students, but not for high-ability students. Lowability students benefit from being with more able peers but not in very homogenous groups, and they are harmed by heterogeneity unless they are placed in a high-ability group.’[42] (p. 559)

‘even more problematic if teachers in low tracks do not adapt their instruction to target the needs of students who struggle academically, leading the gains among high achievers not to be large enough to compensate for the losses of low performing students’.[45] (p. 121)

3.4. Gender

3.5. Disability

3.6. Age

‘has important implications for developmental theory and research. This is strong evidence of the important role that the social context plays in children’s behavioral development […] A phenomenon that may have been assumed originally to be due to the age of the child could also, or instead, be due to the context in which children are observed’.[48] (p. 323–324)

4. Discussion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dewey, J. Education as a Social Function. In Democracy and Education; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1916; pp. 10–22. [Google Scholar]

- Little, W.; Vyain, S.; Scaramuzzo, G.; Cody-Rydzewski, S.; Griffiths, H.; Strayer, E.; Keirns, N. Introduction to Sociology-1st Canadian Edition; BC Campus: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A.; Duneier, M.; Appelbaum, R.P.; Carr, D.S. Introduction to Sociology; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. A Secure Base; Routledge: Padstow, Cornwall, UK, 2005; Available online: https://www.routledge.com/A-Secure-Base/Bowlby/p/book/9780415355278 (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Vila, I. Familia y escuela: Dos contextos y un solo niño. Aula Innovación Educ. 1995, 4, 72–76. [Google Scholar]

- Cebolla-Boado, H.; Radl, J.; Salazar, L. Aprendizaje y ciclo vital. In La Desigualdad de Oportunidades Desde la Educación Preescolar Hasta la Edad Adulta; Fundación La Caixa: Barcelona, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Javier, M.V.L. Ancheta Arrabal, A. La escuela infantil hoy: La escuela infantil hoy. Perspectivas Internacionales de la Educación y la Atención a la Primera Infancia; Valencia, Spain, 2011. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3838325 (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Dreeben, R. the contribution of schooling to the learning of norms. Harv. Educ. Rev. 1967, 37, 211–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantine, J.H.; Hammack, F.M. The Sociology of Education; Pearson Higher Ed.: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gracey, H.L. Learning the student role: Kindergarten as academic boot camp. In Schools and Society: A Sociological Approach to Education, 5th ed.; Ballantine, J.H., Spade, J.Z., Eds.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 147–152. [Google Scholar]

- Galán, R.P. Los nuevos retos del aprendizaje social en niños con necesidades educativas especiales: El aprendizaje en comunidad o la comunidad de aprendizaje en el aula. Rev. Educ. 2009, 348, 443–464. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, B. Approaches to equity in policy for lifelong learning. In Education and Training Policy Division, OECD; OECD: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán, J.; Montané, A.; Gabaldón-Estevan, D. Higher education in Spain: Framework for equity. In Equity in Higher Education. A Global Perspective; Paivandi, S., Joshi, K.M., Eds.; Studera Press: New Delhi, India, 2016; pp. 149–185. [Google Scholar]

- Põder, K.; Kerem, K.; Lauri, T. Efficiency and Equity within European Education Systems and School Choice Policy: Bridging qualitative and quantitative approaches. J. Sch. Choice 2013, 7, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights School Segregation Still Deprives Many Children of Quality Education. Position Paper. 2017. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/commissioner/-/school-segregation-still-deprives-many-children-of-quality-education (accessed on 24 August 2020).

- Ridao-Cano, C.; Bodewig, C. Growing United: Upgrading Europe’s Convergence Machine: Overview (English); World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/852701520358672738/Overview (accessed on 24 August 2020).

- Gabaldón-Estevan, D. Educación y Atención a la Primera Infancia en la Ciudad de Valencia; Editorial Universitat Politècnica de València: Valencia, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Colom-Ortiz, F.; Gabaldón-Estevan, D. Recursos educativos y primera infancia: Privatización de la educación infantil de primer ciclo en la ciudad de Valencia. RASE 2016, 9, 277–298. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Esquinas, F. Elección de escuela: Efectos sociales y dilemas en el sistema educativo público en Andalucía. Rev. Educ. 2004, 334, 377–390. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Mellizo, M.; Martínez-García, J.S. Inequality of educational opportunities: School failure trends in Spain (1977–2012). Int. Stud. Sociol. Educ. 2017, 26, 267–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, P.; Randall, E.V. Exit and entry: Why parents in Utah left public schools and chose private schools. J. Sch. Choice 2009, 3, 242–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyon, J. Social class and the hidden curriculum of work. J. Educ. 1980, 162, 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, F.J.; Martínez-Garrido, C. Magnitud de la segregación escolar por nivel socioeconómico en España y sus Comunidades Autónomas y comparación con los países de la Unión Europea. Rev. Sociol. Educ. 2018, 11, 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. The PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine-Clark, M.; Gil, E. A comparative analysis of social sciences citation tools. In Online Information Review; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, D.R.; Johnson, D.W. The effects of perspective-taking and egocentrism on problem solving in heterogeneous and homogeneous groups. J. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 102, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, R.T.; Scott, L. The effects of cooperative and individualized instruction on student attitudes and achievement. J. Soc. Psychol. 1978, 104, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.W.; Maruyama, G.; Johnson, R.; Nelson, D.; Skon, L. Effects of cooperative, competitive, and individualistic goal structures on achievement: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1981, 89, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldripl, B.G.; Fisher, D.L. A culturally sensitive learning environment instrument for use in science classrooms: Development and validation. In Proceedings of the 21st Annual Conference of the Western Australian Science Education Association, Mount Lawley, Australia, 29 November 1996; Volume 188, p. 188. [Google Scholar]

- Peralta, N.S.; Roselli, N.D.; Borgobello, A. El conflicto sociocognitivo como instrumento de aprendizaje en contextos colaborativos. Interdisciplinaria 2012, 29, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kärner, T.; Warwas, J. Functional relevance of students’ prior knowledge and situational uncertainty during verbal interactions in vocational classrooms: Evidence from a mixed-methods study. Empir. Res. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2015, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Barrio-Parra, F.; Izquierdo-Díaz, M.; Bolonio, D.; Sánchez-Palencia, Y.; Fernández-GutiérrezdelAlamo, L.; Mazadiego, L. Flip Teaching vs Collaborative learning to deal with Heterogeneity in large groups of students. In Proceedings of the 13th International Technology, Education and Development Conference, Valencia, Spain, 11–13 March 2019; pp. 212–218. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Zeng, Q.; Peng, Z. Creating the Recognition of Heterogeneity in Circle Rituals: An Ethnographic Study in a German Primary School. Sage Open 2020, 10, 2158244019899440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooij, T. Secondary school teachers’ personal and school characteristics, experience of violence and perceived violence motives. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 2011, 17, 227–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, C. Dealing with diversity and social heterogeneity: Ambivalences, challenges and pitfalls for pedagogical activity. In International Handbook of Migration, Minorities and Education; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 331–347. [Google Scholar]

- García-Sánchez, I.M. The everyday politics of “cultural citizenship” among North African immigrant school children in Spain. Lang. Commun. 2013, 33, 481–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, T.M.; Marcelo, A.K. Through race-colored glasses: Preschoolers’ pretend play and teachers’ ratings of preschooler adjustment. Early Child. Res. Q. 2014, 29, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penney, J. Racial interaction effects and student achievement. Educ. Financ. Policy 2017, 12, 447–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Hurtado, J. The Role of Teachers on Students’peer Groups Relations: A Review on Their Influence on School Engagement and Academic Achievement. Límite 2018, 13, 30–43. [Google Scholar]

- McGlothlin, H.; Killen, M. Children’s perceptions of intergroup and intragroup similarity and the role of social experience. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2005, 26, 680–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J. Prejudice in the classroom: A longitudinal analysis of anti-immigrant attitudes. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2019, 42, 1514–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booij, A.S.; Leuven, E.; Oosterbeek, H. Ability peer effects in university: Evidence from a randomized experiment. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2017, 84, 547–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, J.; Liu, L.; Du, Y. Benefits of a highly entitative class for adolescents’ psychological well-being in school. Sch. Ment. Health 2019, 11, 766–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, S.; Banoglu, K. Hogging the Middle Lane: How Student Performance Heterogeneity Leads Turkish Schools to Fail in PISA? Cypriot J. Educ. Sci. 2018, 13, 448–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Marotta, L. Peer effects in early schooling: Evidence from Brazilian primary schools. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 82, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, L.; Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, R.; Wilderson, F. Effects of cooperative, competitive, and individualistic experiences on interpersonal attraction among heterogeneous peers. J. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 111, 243–252. [Google Scholar]

- Winsler, A.; Caverly, S.L.; Willson-Quayle, A.; Carlton, M.P.; Howell, C.; Long, G.N. The social and behavioral ecology of mixed-age and same-age preschool classrooms: A natural experiment. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2002, 23, 305–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decristan, J.; Fauth, B.; Kunter, M.; Büttner, G.; Klieme, E. The interplay between class heterogeneity and teaching quality in primary school. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 86, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.L.; Kornienko, O.; Schaefer, D.R.; Hanish, L.D.; Fabes, R.A.; Goble, P. The Role of Sex of Peers and Gender-Typed Activities in Young Children’s Peer Affiliative Networks: A Longitudinal Analysis of Selection and Influence. Child Dev. 2013, 84, 921–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conlan, A.J.; Eames, K.T.; Gage, J.A.; von Kirchbach, J.C.; Ross, J.V.; Saenz, R.A.; Gog, J.R. Measuring social networks in British primary schools through scientific engagement. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2011, 278, 1467–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, R.T. Integrating severely adaptively handicapped seventh-grade students into constructive relationships with nonhandicapped peers in science class. Am. J. Ment. Defic. 1983, 87, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Perez Galan, R. The new challenges of social learning for children with special educational needs. Learning in the community, or the community of learning in the classroom. Rev. Educ. 2009, 348, 271–272. [Google Scholar]

- Hawley, W. The false premises and false promises of the movement to privatize public education. Teach. Coll. Rec. 1995, 96, 735–742. [Google Scholar]

- Teese, R. Curriculum Hierarchy, Private Schooling, and the Segmentation of Australian Secondary Education, 1947—1985. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 1998, 19, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, A.M. Peer groups as a context for the socialization of adolescents’ motivation, engagement, and achievement in school. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 35, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, A.M. The peer group as a context for the development of young adolescent motivation and achievement. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 1135–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiuru, N.; Aunola, K.; Nurmi, J.E.; Leskinen, E.; Salmela-Aro, K. Peer group influence and selection in adolescents’ school burnout: A longitudinal study. Merrill Palmer Q. 2008, 54, 23–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granell Pérez, R.G.; Fuenmayor Fernández, A. La calidad de la educación infantil: La opinión de los padres. In VIII Encuentro de Economía Pública; VIII Encuentro de Economía Pública: Cáceres, Spain, 2001; p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Bosetti, L.; Pyryt, M.C. Parental motivation in school choice: Seeking the competitive edge. J. Sch. Choice 2007, 1, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, R. Selling education through “culture”: Responses to the market by new, non-government schools. Aust. Educ. Res. 2009, 36, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatcher, R. Class differentiation in education: Rational choices? Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 1998, 19, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, P.M.; Jennings, J.L. Choice, Information, and Constrained Options School Transfers in a Stratified Educational System. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2015, 80, 1069–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, C.; Maxwell, C. Parenting priorities and pressures: Furthering understanding of ‘concerted cultivation’. Discourse Stud. Cult. Politics Educ. 2016, 37, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancebón, M.J.; Pérez-Ximénez, D. Conciertos educativos y selección académica y social del alumnado. Hacienda Pública Española 2007, 180, 125–154. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Enguita, M. Escuela pública y privada en España: La segregación rampante. RASE 2008, 1, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Llera, R.; Muñiz-Pérez, M. Colegios concertados y selección de escuela en España: Un círculo vicioso. Presup. Y Gasto Público 2012, 67, 97–118. [Google Scholar]

| Search Terms | WOS | Scopus | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| “school homogeneity” AND “classroom interactions” | 10 | 5 | 12 |

| “school heterogeneity” AND “classroom interactions” | 23 | 23 | 34 |

| Total | 32 | 25 | 42 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gabaldón-Estevan, D. Heterogeneity versus Homogeneity in Schools: A Study of the Educational Value of Classroom Interaction. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10110335

Gabaldón-Estevan D. Heterogeneity versus Homogeneity in Schools: A Study of the Educational Value of Classroom Interaction. Education Sciences. 2020; 10(11):335. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10110335

Chicago/Turabian StyleGabaldón-Estevan, Daniel. 2020. "Heterogeneity versus Homogeneity in Schools: A Study of the Educational Value of Classroom Interaction" Education Sciences 10, no. 11: 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10110335

APA StyleGabaldón-Estevan, D. (2020). Heterogeneity versus Homogeneity in Schools: A Study of the Educational Value of Classroom Interaction. Education Sciences, 10(11), 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10110335