Bringing Out-of-School Learning into the Classroom: Self- versus Peer-Monitoring of Learning Behaviour

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Bringing the Science Centre into Schools

1.2. Structure and Autonomy Support

1.2.1. What Is the Right Degree of Structure?

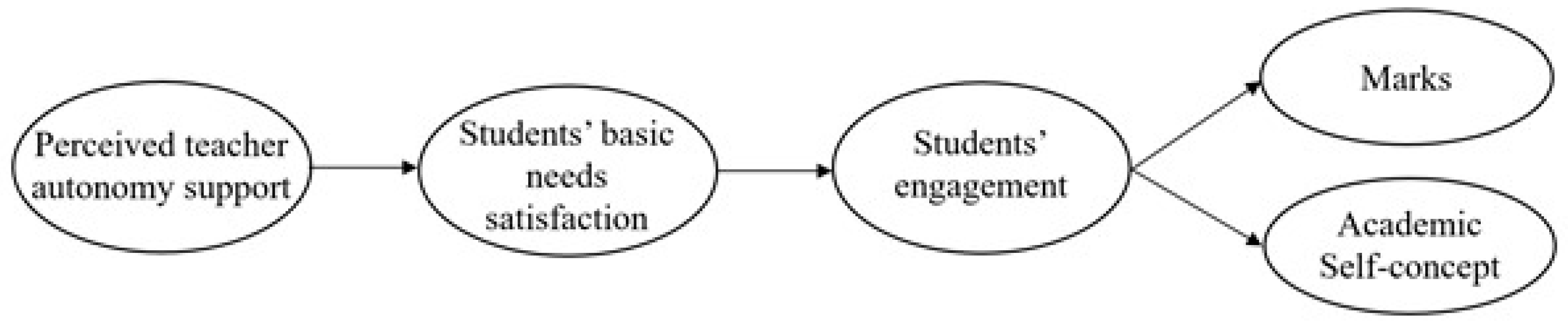

1.2.2. Intrinsic Motivation as a Predictor for Students’ Engagement and Academic Success

1.3. Peer- versus Self-Monitoring to Regulate Students’ Learning Behaviour

1.4. Study Question

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Instructional Concept

- sorting of different products based on their ingredients and the process of degradation;

- using vision to compare natural and synthetic fibre structures with a microscope;

- using touch in a haptic comparison of natural and synthetic fibre structures;

- smelling and tasting of natural products used as food colorants and their assignment to associated products.

- 5.

- a miniature model of a biogas plant;

- 6.

- an “energy organ” consisting of eight columns (energy “content” of 1 kW each) filled with renewable and fossil fuels. Students compared volumes and energy values of renewable and fossil fuels;

- 7.

- the production of sunflower oil with a manual seed press, including its tasting and burning (conducted under supervision).

2.2. Workbook Guidance

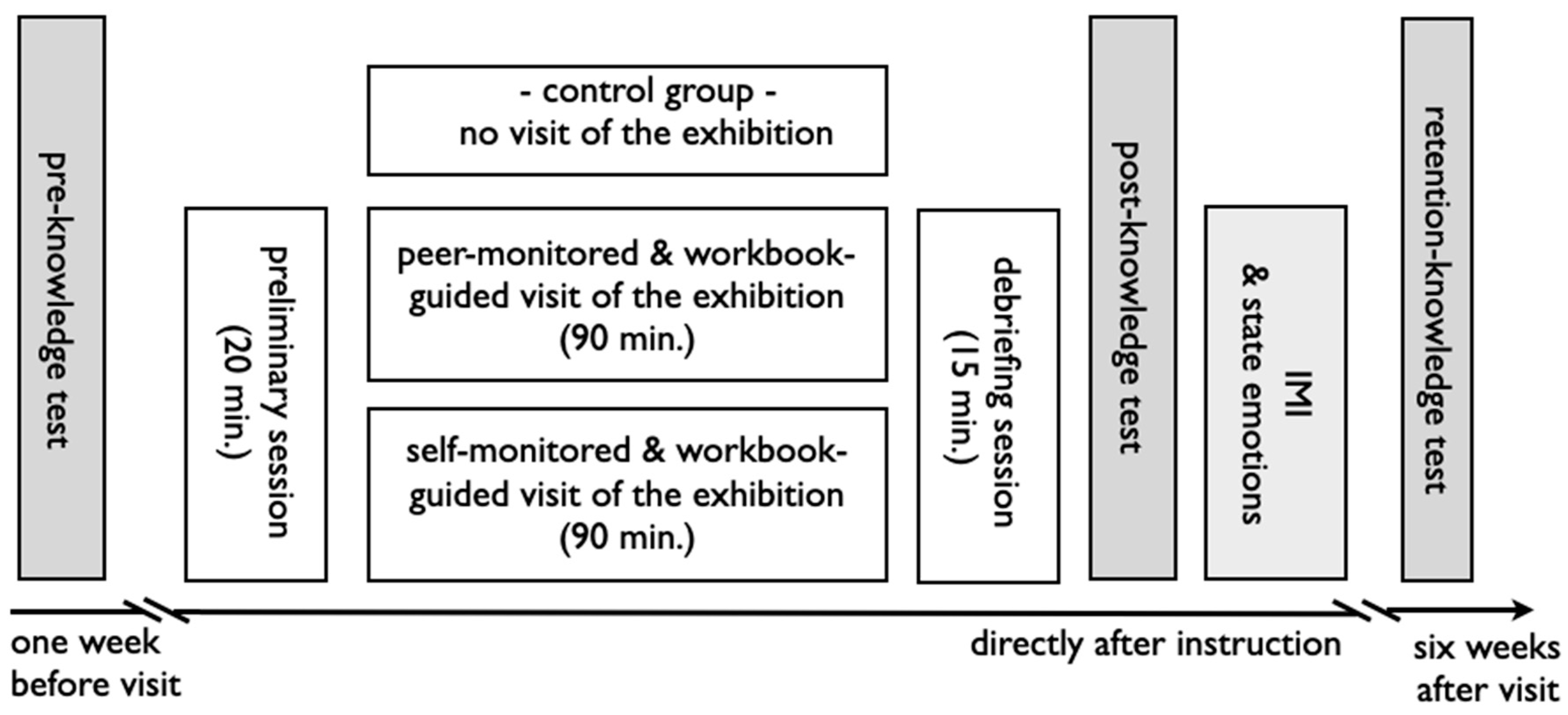

2.3. Implementation

2.4. Self- versus Peer-Monitoring

2.4.1. Measurement of Science Learning Outcomes

2.4.2. Measurement of Predictors for Short-Term Learning Emotions and Intrinsic Motivation

2.5. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Within-Group Comparison of the Control Group

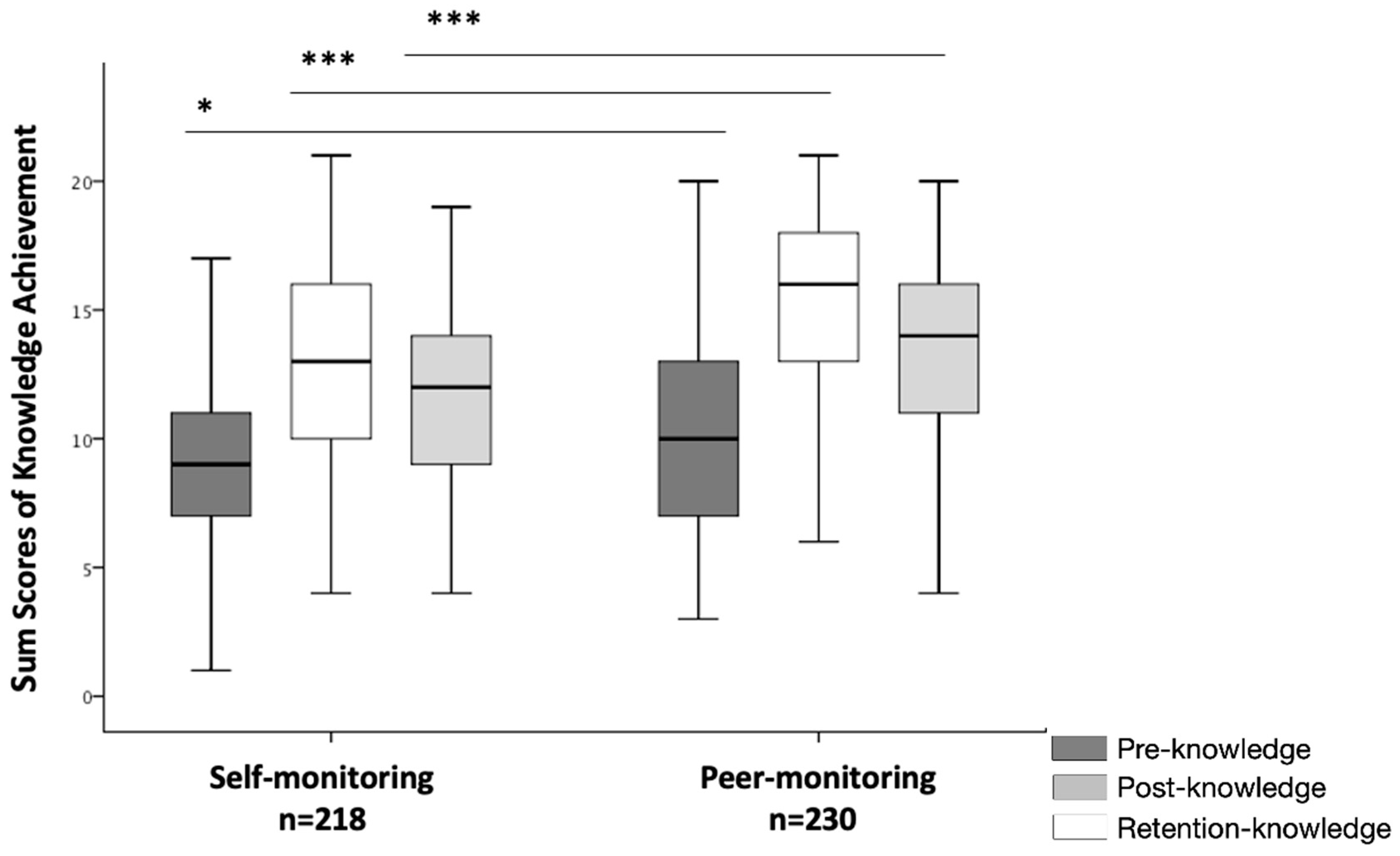

3.2. Science Learning Outcome

3.3. Peer- versus Self-Monitoring

3.4. Short-Term Learning Emotions and Intrinsic Motivation

4. Discussion

4.1. Within-Group Comparison

4.2. Between-Group Comparison (Peer- versus Self-Monitoring)

4.2.1. Science Learning Outcomes

4.2.2. Predictors for Students’ Emotional Engagement

Students’ Intrinsic Motivation

Short-Term Learning Emotions

5. Conclusions

Limitations and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raufelder, D.; Kittler, F.; Braun, S.R.; Lätsch, A.; Wilkinson, R.P.; Hoferichter, F. The interplay of perceived stress, self-determination and school engagement in adolescence. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2014, 35, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, M.; Sancho, P.; Galiana, L.; Tomás, J.M. Autonomy support, psychological needs satisfaction, school engagement and academic success: A mediation model. Univ. Psychol. 2018, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Kim, E.J.; Reeve, J. Longitudinal test of self-determination theory’s motivation mediation model in a naturally occurring classroom context. J. Educ. Psychol. 2012, 104, 1175–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eshach, H. Bridging in-school and out-of-school learning: Formal, non-formal, and informal education. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2007, 16, 171–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwan, S.; Grajal, A.; Lewalter, D. Understanding and Engagement in Places of Science Experience: Science Museums, Science Centers, Zoos, and Aquariums. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 49, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelliott, A. Understanding Gravity: The Role of a School Visit to a Science Centre. Int. J. Sci. Educ. Part B Commun. Public Engagem. 2014, 4, 30–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şentürk, E.; Özdemir, Ö.F. The Effect of Science Centres on Students’ Attitudes Towards Science. Int. J. Sci. Educ. Part B Commun. Public Engagem. 2014, 4, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J.H.; Needham, M.; Dierking, L.; Prendergast, L. International Science Centre Impact Study Final Report; University Press: Corvallis, OR, USA, 2014; p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, S. Designs for learning: Studying science museum exhibits that do more than entertain. Sci. Educ. 2004, 88, S17–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWitt, J.; Storksdieck, M. A short review of school field trips: Key findings from the past and implications for the future. Visit. Stud. 2008, 11, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anderson, D.; Kisiel, J.; Storksdieck, M. Understanding Teachers’ Perspectives on Field Trips: Discovering Common Ground in Three Countries. Curator Museum J. 2006, 49, 365–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J.H.; Dierking, L. Lessons without Limit: How Free-Choice Learning Is Transforming Education; AltaMira Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, D.; Zhang, Z. Teacher Perceptions of Field-Trip Planning and Implementation. Visit. Stud. Today 2003, VI, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kisiel, J.F. Teachers, Museums and Worksheets: A Closer Look at a Learning Experience. J. Sci. Teacher Educ. 2003, 14, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisiel, J. Understanding elementary teacher motivations for science fieldtrips. Sci. Educ. 2005, 89, 936–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storksdieck, M. Differences in teachers’ and students’ museum field-trip experiences. Visit. Stud. Today 2001, 4, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Bobick, B.; Hornby, J. Practical Partnerships: Strengthening the Museum-School Relationship. J. Museum Educ. 2013, 38, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, Y.C.; Buchholz, H.; Brosda, C.; Bogner, F.X. Evaluation of a portable and interactive augmented reality learning system by teachers and students. Augment. Real. Educ. 2011, 2011, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A.C.; Scanlon, E.; Clough, G. Mobile learning: Two case studies of supporting inquiry learning in informal and semiformal settings. Comput. Educ. 2013, 61, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Reeve, J.; Deci, E.L. Engaging Students in Learning Activities: It is Not Autonomy Support or Structure but Autonomy Support and Structure. J. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 102, 588–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheon, S.H.; Reeve, J.; Vansteenkiste, M. When teachers learn how to provide classroom structure in an autonomy-supportive way: Benefits to teachers and their students. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2020, 90, 103004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox-Petersen, A.M.; Marsh, D.D.; Kisiel, J.; Melber, L.M. Investigation of guided school tours, student learning, and science reform recommendations at a museum of natural history. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2003, 40, 200–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisiel, J.F. Examining teacher choices for science museum worksheets. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 2007, 18, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloe, A.M.; Shisler, S.M.; Norris, B.D.; Nickerson, A.B.; Rinker, T.W. A multivariate meta-analysis of student misbehavior and teacher burnout. Educ. Res. Rev. 2014, 12, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glackin, M. Control must be maintained: Exploring teachers’ pedagogical practice outside the classroom. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2018, 39, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, P.M. Topics in museums and science education. Stud. Sci. Educ. 1992, 20, 157–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramey-Gassert, L.; Walberg, H.J.; Walberg, H.J. Reexamining connections: Museums as science learning environments. Sci. Educ. 1994, 78, 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J.H. Testing a museum exhibition design assumption: Effect of explicit labeling of exhibit clusters on visitor concept development. Sci. Educ. 1997, 81, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschner, P.A.; Sweller, J.; Clark, R.E. Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching. Educ. Psychol. 2006, 41, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.E. Should There Be a Three-Strikes Rule against Pure Discovery Learning? The Case for Guided Methods of Instruction. Am. Psychol. 2004, 59, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sweller, J.; Kirschner, P.A.; Clark, R.E. Why minimally guided teaching techniques do not work: A reply to commentaries. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 42, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfieri, L.; Brooks, P.J.; Aldrich, N.J.; Tenenbaum, H.R. Does Discovery-Based Instruction Enhance Learning? J. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 103, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ames, C. Classrooms: Goals, structures, and student motivation. J. Educ. Psychol. 1992, 84, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantuzzo, J.W.; King, J.A.; Heller, L.R. Effects of Reciprocal Peer Tutoring on Mathematics and School Adjustment: A Component Analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 1992, 84, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Stiller, J. The social contexts of internalization: Parent and teacher influences on autonomy, motivation, and learning. Adv. Motiv. Achiev. 1991, 7, 115–149. [Google Scholar]

- Stipek, D.J. Motivation and instruction. Handb. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 1, 85–113. [Google Scholar]

- Bamberger, Y.; Tal, T. Learning in a personal context: Levels of choice in a free choice learning environment in science and natural history museums. Sci. Educ. 2007, 91, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberger, Y.; Tal, T. An experience for the lifelong journey: The long-term effect of a class visit to a science center. Visit. Stud. 2008, 11, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWitt, J.; Hohenstein, J. School trips and classroom lessons: An investigation into teacher-student talk in two settings. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2010, 47, 454–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, T.; Pell, A. Factors influencing elementary school children’s attitudes toward science before, during, and after a visit to the UK National Space Centre. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2005, 42, 53–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tal, R.; Bamberger, Y.; Morag, O. Guided school visits to natural history museums in Israel: Teachers’ roles. Sci. Educ. 2005, 89, 920–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randler, C.; Bogner, F.X. Cognitive achievements in identification skills. J. Biol. Educ. 2006, 40, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M.; Williams, G.C. Need satisfaction and the self-regulation of learning. Learn. Individ. Differ. 1996, 8, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Facilitating optimal motivation and psychological well-being across life’s domains. Can. Psychol. 2008, 49, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grolnick, W.S.; Ryan, R.M. Parent Styles Associated with Children’s Self-Regulation and Competence in School. J. Educ. Psychol. 1989, 81, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.T.; Peck, S.C. Adolescent educational success and mental health vary across school engagement profiles. Dev. Psychol. 2013, 49, 1266–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Connell, J.P. Context, self, and action: A motivational analysis of self-system processes across the life span. Self Transit. Infancy Child. 1990, 8, 61–97. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Self-Regulated Learning and Academic Achievement: An Overview. Educ. Psychol. 1990, 25, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voelkl, K.E. Identification with school. Am. J. Educ. 1997, 105, 294–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, R.M. Cooperative learning: Review of research and practice. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2016, 41, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Topping, K.; Buchs, C.; Duran, D.; Van Keer, H. Effective Peer Learning: From Principles to Practical Implementation; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–185. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, K.C. An updated meta-analysis on the effect of peer tutoring on tutors’ achievement. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2019, 40, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenbaum, H.R.; Winstone, N.E.; Leman, P.J.; Avery, R.E. How Effective Is Peer Interaction in Facilitating Learning? A Meta-Analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 112, 1303–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harris, K.R.; Friedlander, B.D.; Saddler, B.; Frizzelle, R.; Graham, S. Self-monitoring of attention versus self-monitoring of academic performance: Effects among students with ADHD in the general education classroom. J. Spec. Educ. 2005, 39, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lan, W.Y. The effects of self-monitoring on students’ course performance, use of learning strategies, attitude, self-judgment ability, and knowledge representation. J. Exp. Educ. 1996, 2, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.C.; Topping, K.J.; Henington, C.; Skinner, C.H. Peer monitoring of learning behaviour: The case of ‘Checking chums’. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 1999, 15, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J.; Schunk, D.H. Handbook of Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, L.M.; Eveleigh, E.L. A review of the effects of self-monitoring on reading performance of students with disabilities. J. Spec. Educ. 2011, 45, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, M.A. Self-Management Strategies to Support Students with ASD. Teach. Except. Child. 2016, 48, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handa, K.; Noro, F. Effects of Self-Monitoring Package to Improve Social Skill of Students With Autism Spectrum Disorders in Japanese Regular Classrooms. J. Spec. Educ. Res. 2016, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.; Witte, R. Self-Management and Peer-Monitoring within a group contingency to decrease uncontrolled verbalizations of children with Attention-Deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychol. Sch. 2000, 37, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briesch, A.M.; Briesch, J.M. Meta-analysis of behavioral self-management interventions in single-case research. School Psych. Rev. 2016, 45, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, A.; McDougall, D. Self-Monitoring of Pace to Improve Math Fluency of High School Students with Disabilities. Behav. Anal. Pract. 2008, 1, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Henington, C.; Skinner, C.H. Peer-monitoring. In Peer Assisted Learning; Topping, K., Ehly, S., Eds.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 237–253. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, R. Research in self-monitoring with students with learning disabilities: The present, the prospects, the pitfalls. J. Learn. Disabil. 1996, 29, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mooney, P.; Ryan, J.B.; Uhing, B.M.; Reid, R.; Epstein, M.H. A review of self-management interventions targeting academic outcomes for students with emotional and behavioral disorders. J. Behav. Educ. 2005, 14, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, C.H.; Cashwell, T.H.; Skinner, A.L. Increasing tootling: The effects of a peer-monitored group contingency program on students’ reports of peers’ prosocial behaviors. Psychol. Sch. 2000, 37, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Ok, M.W.; Yoo, Y. The Effects of Self- and Peer-Monitoring in Social Studies Performance of Students with Learning Disabilities and Low Achieving Students. Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 2018, 33, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee of the United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New Era Glob. Heal. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, P.; Pietarinen, J.; Havu-Nuutinen, S.; Pelkonen, P. Young citizens’ knowledge and perceptions of bioenergy and future policy implications. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 3058–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dael, M.; Lizin, S.; Swinnen, G.; Van Passel, S. Young people’s acceptance of bioenergy and the influence of attitude strength on information provision. Renew. Energy 2017, 107, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radics, R.; Dasmohapatra, S.; Kelley, S.S. Systematic review of bioenergy perception studies. BioResources 2015, 10, 8770–8794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guven, G.; Sulun, Y. Pre-service teachers’ knowledge and awareness about renewable energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 80, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.; Lucas, K.B. The effectiveness of orienting students to the physical features of a science museum prior to visitation. Res. Sci. Educ. 1997, 27, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewitt, J.; Osborne, J. Recollections of exhibits: Stimulated- recall interviews with primary school children about science centre visits. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2010, 32, 1365–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollar, I.; Fischer, F.; Hesse, F.W. Collaboration scripts–a conceptual analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 18, 159–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krombaß, A.; Harms, U. Acquiring knowledge about biodiversity in a museum—Are worksheets effective? J. Biol. Educ. 2008, 42, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortz, J.; Döring, N. Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation für Human- und Sozialwissenschaftler; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Oksenholt, S.; Lienert, G.A. Testaufbau und Testanalyse; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bogner, F.X. The Influence of Short-Term Outdoor Ecology Education on Long-Term Variables of Environmental Perspective. J. Environ. Educ. 1998, 29, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharfenberg, F.-J.; Bogner, F.X.; Klautke, S. The suitability of external control-groups for empirical control purposes: A cautionary story in science education research. Electron. J. Sci. Educ. 2006, 11, 22–36. [Google Scholar]

- Schaal, S.; Bogner, F.X. Human visual perception—Learning at workstations. J. Biol. Educ. 2005, 40, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M. Control and information in the intrapersonal sphere: An extension of cognitive evaluation theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1982, 43, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gläser-Zikuda, M.; Fuß, S.; Laukenmann, M.; Metz, K.; Randler, C. Promoting students’ emotions and achievement—Instructional design and evaluation of the ECOLE-approach. Learn. Instr. 2005, 15, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meissner, B.; Bogner, F. Enriching students’ education using interactive workstations at a salt mine turned science center. J. Chem. Educ. 2011, 88, 510–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics. And Sex and Drugs and Rock’n’Roll; Sage: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wassertheil, S.; Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Biometrics 1970, 26, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hascher, T. Well-being in school—Why students need social support. Lerning Emot. Influ. Affect. Factors Classr. Learn. 2003, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R.; Goetz, T.; Frenzel, A.C.; Barchfeld, P.; Perry, R.P. Measuring emotions in students’ learning and performance: The Achievement Emotions Questionnaire (AEQ). Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 36, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Griffin, J.; Symington, D. Moving from task-oriented to learning-oriented strategies on school excursions to museums. Sci. Educ. 1997, 81, 763–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rix, C.; McSorley, J. An investigation into the role that school-based interactive science centres may play in the education of primary-aged children. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 1999, 21, 577–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, M.F.; Smart, K. Free-choice worksheets increase students’ exposure to curriculum during museum visits. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2007, 44, 1389–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mccurdy, B.L.; Shapiro, E.S. A Comparison of Teacher-, Peer-, and Self-Monitoring with Curriculum-Based Measurement in Reading Among Students with Learning Disabilities. J. Spec. Educ. 1992, 26, 162–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, S.; Wanzek, J.; Swanson, E.A.; Vaughn, S. Team-based learning for students with high-incidence disabilities in high school social studies classrooms. Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 2015, 30, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.A. Making sense of participatory evaluation practice. New Dir. Eval. 1998, 1998, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharfenberg, F.J.; Bogner, F.X.; Klautke, S. A category-based video analysis of students’ activities in an out-of-school hands-on gene technology lesson. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2008, 30, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.C.; Deci, E.L. Internalization of Biopsychosocial Values by Medical Students: A Test of Self-Determination Theory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 767–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsburg-Block, M.D.; Rohrbeck, C.A.; Fantuzzo, J.W. A meta-analytic review of social, self-concept, and behavioral outcomes of peer-assisted learning. J. Educ. Psychol. 2006, 98, 732–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrbeck, C.A.; Ginsburg-Block, M.D.; Fantuzzo, J.W.; Miller, T.R. Peer-assisted learning interventions with elementary school students: A meta-analytic review. J. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 95, 240–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, C.; Vom Lehn, D. Configuring “interactivity”: Enhancing engagement in science centres and museums. Soc. Stud. Sci. 2008, 38, 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J.H.; Dierking, L.D. Learning from Museums: Visitor Experiences and the Making of Meaning, 2nd ed.; Rowman and Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Price, S.; Hein, G.E. More than a field trip: Science programmes for elementary school groups at museums. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 1991, 13, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainley, M. Connecting with learning: Motivation, affect and cognition in interest processes. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 18, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randler, C. Association Between Emotional Variables and School Achievement. Int. J. Instr. 2009, 2, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hidi, S.; Berndorff, D.; Ainley, M. Children’s argument writing, interest and self-efficacy: An intervention study. Learn. Instr. 2002, 12, 429–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R.; Goetz, T.; Titz, W.; Perry, R.P. Academic emotions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: A program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 37, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R.; Goetz, T.; Daniels, L.M.; Stupnisky, R.H.; Perry, R.P. Boredom in Achievement Settings: Exploring Control-Value Antecedents and Performance Outcomes of a Neglected Emotion. J. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 102, 531–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dewey, J. Logic: The Theory of Inquiry. John Dewey: The Latter Works; A. Boydston: Carbondale, IL, USA, 1991; Volume 4, pp. 1925–1953. [Google Scholar]

- Topping, K.J. Trends in peer learning. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 25, 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Stiller, J.D.; Lynch, J.H. Representations of Relationships to Teachers, Parents, and Friends as Predictors of Academic Motivation and Self-Esteem. J. Early Adolesc. 1994, 14, 226–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, C.A.; Olstad, R.G. Effects of novelty-reducing preparation on exploratory behavior and cognitive learning in a science museum setting. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 1991, 28, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennie, L.J. Learning Science Outside of School Handbook of Research on Science Education; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 125–167. [Google Scholar]

- Sarason, I.G. Stress, anxiety, and cognitive interference: Reactions to tests. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 46, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colley, H.; Hodkinson, P.; Malcom, J. Informality and Formality in Learning: A Report for the Learning and Skills Research Centre; University of Leeds: Leeds, UK, 2004; ISBN 1853389145. [Google Scholar]

| Reader Read out to the Rest of the Group… | Moderator Monitored That Peers… | Material Guard Monitored That Peers… | Inspector Monitored That Peers… |

|---|---|---|---|

| short operating procedures at each exhibit. | stayed focused on the topic. | handled materials with care. | tried to solve all exhibit related activities. |

| information written down in the workbook. | did not disturb other groups and worked quietly (measured by a sound level meter). | left each exhibit tidy and neat. | recorded all results in the workbook. |

| finished each exhibit-related task that had been started. | finished activities before the comparison of own results with provided solutions. |

| 1. Which Plant Is Used for Liquid Fuel Production in Germany? | 2. Which Source of Energy Is Based on Mineral Oil? | 3. The Origin of Bioenergy Is Based on… | 4. Mineral Oil Arises from… |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) barley | (a) gasoline | (a) wind | (a) dinosaur fossils |

| (b) rye | (b) heating oil | (b) sunlight | (b) underground methane bubbles |

| (c) wheat | (c) biodiesel | (c) water | (c) emissions of black smokers in the deep sea |

| (d) rape | (d) plastic | (d) geothermal energy | (d) dead marine organisms |

| Self-Monitored Group (n = 218) | Peer-Monitored Group (n = 230) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T1 | T2 | T3 | |

| 25th/75th P | 7.0/11.0 | 10.0/16.25 | 9.0/14.0 | 7.0/13.0 | 13.0/18.0 | 10.8/16.0 |

| Median | 9.0 | 13.0 | 12.0 | 10.0 | 16.0 | 14.0 |

| T1:T2 | T1:T3 | T2:T3 | T1:T2 | T1:T3 | T2:T3 | |

| z | −11.52 | −8.84 | −6.20 | −12.31 | −10.62 | −9.56 |

| p | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** |

| r | −0.78 | −0.60 | −0.42 | −0.81 | −0.70 | −0.63 |

| Variable | Reference | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | Step 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | peer-mediated | 0.669 ** | 0.687 ** | 0.602 ** | 0.605 ** | 0.691 ** |

| Pre-knowledge | right answer | 0.387 ** | 0.347 ** | 0.353 ** | 0.350 ** | |

| Intervention × Pre-knowledge | 1.230 * | 1.222 * | 1.238 * | |||

| Gender | male | 0.798 ** | 916 | |||

| Intervention × Gender | 0.769 ** | |||||

| Constant | 2.483 ** | 4.296 ** | 4.601 ** | 5.126 ** | 4.795 ** |

| Variable | Reference | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 | Step 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | peer-mediated | 0.752 ** | 0.777 ** | 0.592 ** | 0.593 ** | 0.601 ** |

| Pre-knowledge | right answer | 0.353 ** | 0.281 ** | 0.284 ** | 0.283 ** | |

| Intervention × Pre-knowledge | 1.572 ** | 1.567 * | 1.569 ** | |||

| Gender | male | 0.890 ** | 902 | |||

| Intervention × Gender | 974 | |||||

| Constant | 1.622 ** | 2.901 ** | 3.326** | 3.513** | 3.490 ** |

| Variable | Well-Being | Interest | Boredom | Anxiety | Competence | Choice | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-monitored (n = 152) | (25th/75th P) | 1.3/2.3 | 1.5/2.5 | 2.8/3.5 | 3.3/3.5 | 2/2.5 | 1.6/2.6 |

| Median | 1.8 | 2 | 3 | 3.5 | 2.3 | 2.1 | |

| Peer-monitored (n = 230) | (25th/75th P) | 1.5/2.3 | 1.5/2.5 | 2.8/3.8 | 3.3/4 | 1.8/2.5 | 1.6/2.3 |

| Median | 1.9 | 2 | 3.3 | 3.8 | 2.2 | 2 | |

| Between-group comparison | U | 17254 | 17256 | 15298 | 14810 | 14377 | 16324 |

| z | −0.22 | −0.22 | −2.08 | −2.59 | −2.96 | −1.1 | |

| p | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.04 * | 0.01 ** | 0.003 ** | .27 | |

| r | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.06 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Larsen, Y.C.; Groß, J.; Bogner, F.X. Bringing Out-of-School Learning into the Classroom: Self- versus Peer-Monitoring of Learning Behaviour. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10100284

Larsen YC, Groß J, Bogner FX. Bringing Out-of-School Learning into the Classroom: Self- versus Peer-Monitoring of Learning Behaviour. Education Sciences. 2020; 10(10):284. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10100284

Chicago/Turabian StyleLarsen, Yelva C., Jorge Groß, and Franz X. Bogner. 2020. "Bringing Out-of-School Learning into the Classroom: Self- versus Peer-Monitoring of Learning Behaviour" Education Sciences 10, no. 10: 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10100284

APA StyleLarsen, Y. C., Groß, J., & Bogner, F. X. (2020). Bringing Out-of-School Learning into the Classroom: Self- versus Peer-Monitoring of Learning Behaviour. Education Sciences, 10(10), 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10100284