Farmers Perceptions of Climate Change Related Events in Shendam and Riyom, Nigeria

Abstract

1. Introduction

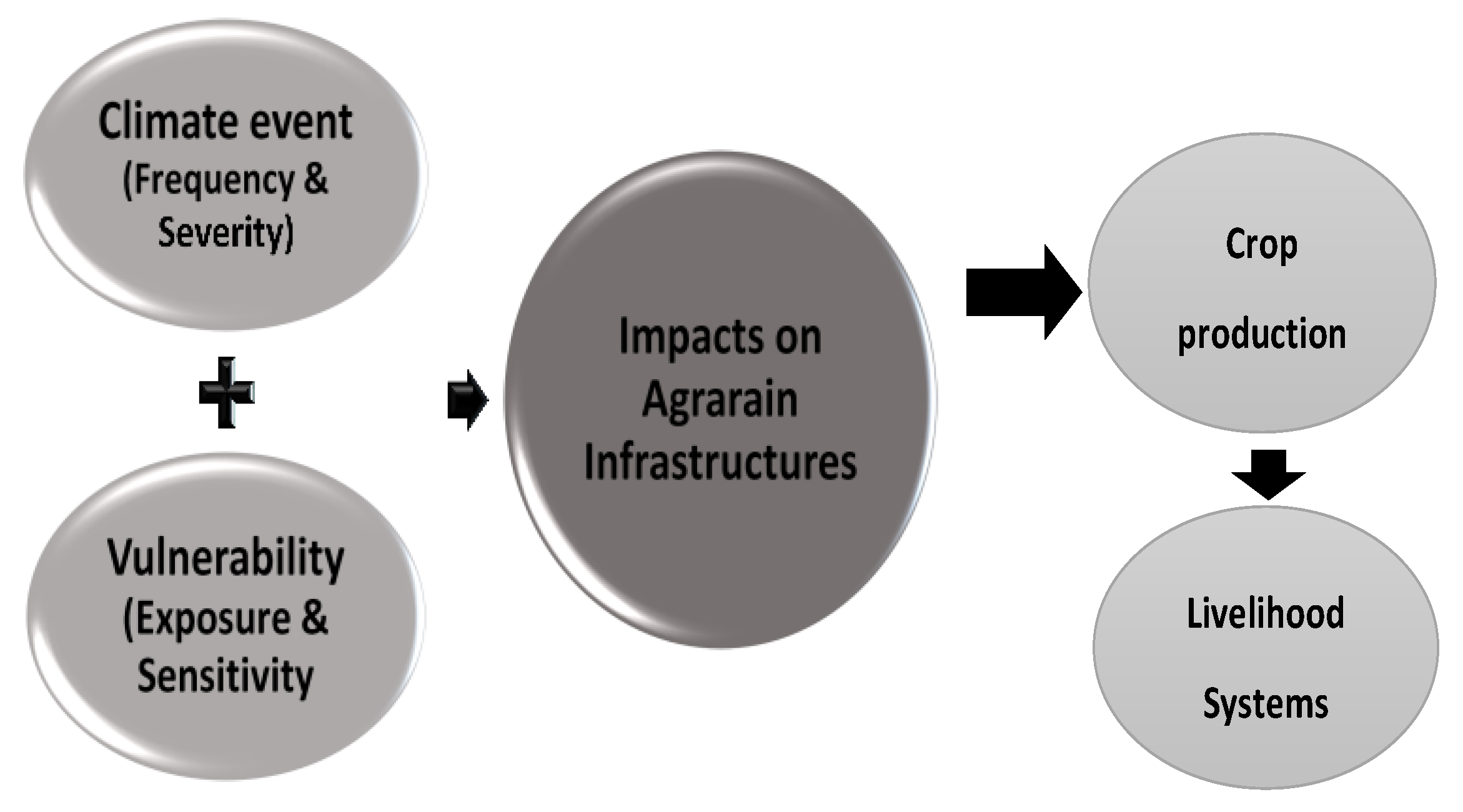

2. Agrarian Infrastructure

- Off-Farm infrastructure:

- ▪

- Transport systems (roads and bridges)

- ▪

- Institutional service systems (agricultural research and extension services)

- On-Farm Infrastructure:

- ▪

- Irrigation systems (dams, tube wells, boreholes)

- ▪

- Inputs (fertilizer, seeds, and farm implements)

Agricultural Infrastructure Policies and Management in Nigeria

3. Climate-Related Events and Their Impacts in Nigeria

4. Methods

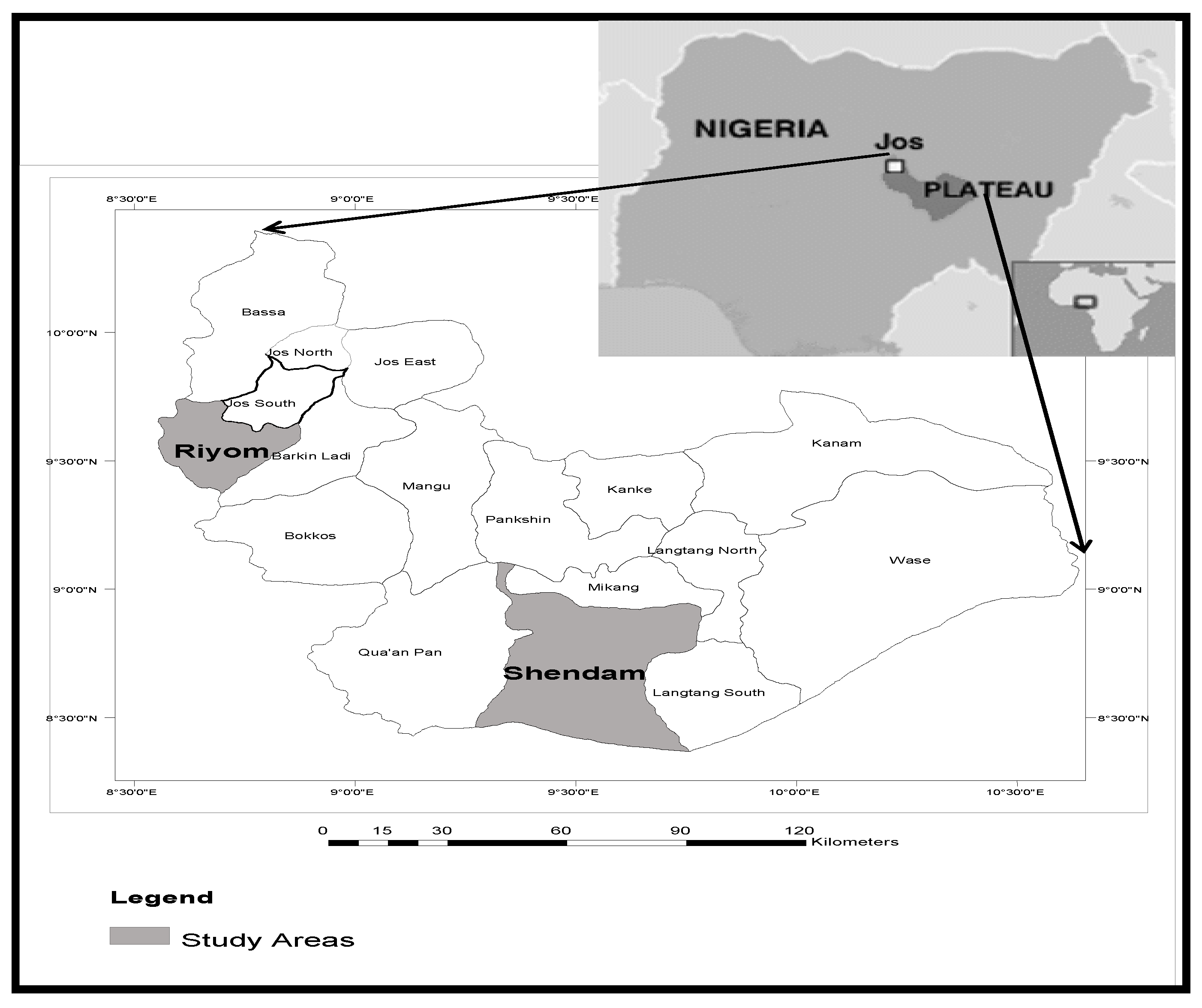

4.1. Study Area Description

4.2. Methodology

4.2.1. Data Collection

4.2.2. Data Analysis

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. The Description of Respondents Characteristics

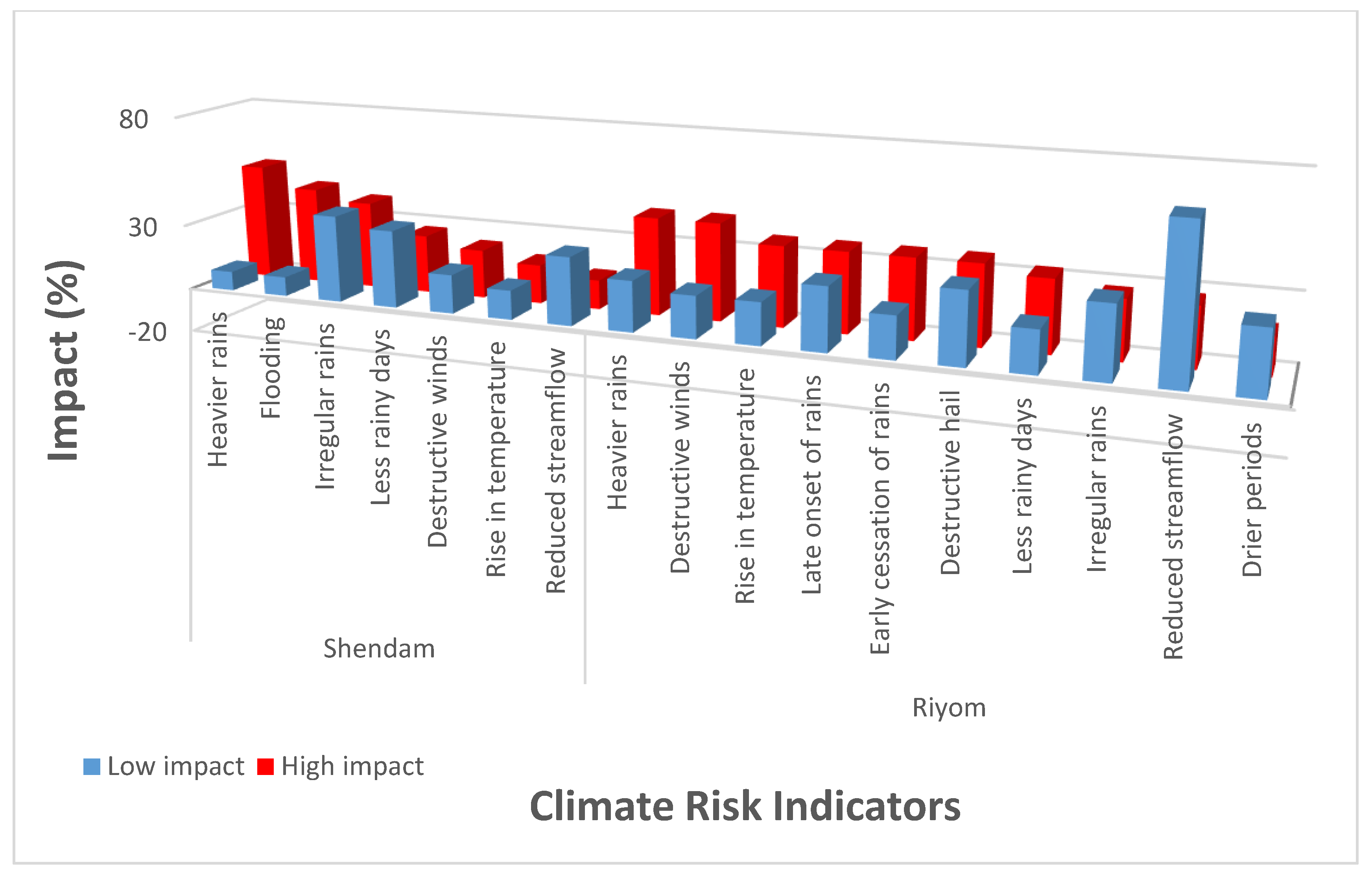

5.2. Indicators of Climate Change

5.3. Impacts of Climate-Related Events on Agrarain Infrastructures

5.3.1. The Impacts of Floods on Agrarian Roads in Shendam

“Our highest problem in Shendam is flood. In the year 2012, several days of heavy downpour caused floods and almost all villages within Shendam suffered. The Shendam town bridge was totally washed away, and two other bridges in the surrounding villages collapsed cutting off the villages”.(I09)

“… serious challenges of flood in Shendam. I think in the entire Plateau state, Shendam is the worst hit by floods. We experience serious floods, which affect our farmers, their farmlands, houses, and some infrastructures. More than 100 hectares of farmland were flooded. Roads connecting to the riverine areas are affected and even cut off. Even within Shendam town, the bridge linking Shendam and Jos road was cut off during the 2012 flood. The bridge linking Shendam to Yelwa was cut off, and the bridge linking Shendam to Kalong was cut off. Three bridges in Shendam were cut off that year. So the people resorted to using canoes”.(I06)

5.3.2. Impacts of Droughts on Irrigation Systems in Riyom

“… in areas where irrigation takes place, the source of water around that area normally lasts up to January- February, but I don’t know what happened … before we knew it, by early December the water dried up. It was a very serious problem and of course there was no magic we could do”.(I19)

“… in recent times, farmers who engage in dry season farming will definitely encounter drought which then deters the growth of the crop”… “We tried all we could, in fact we sank two boreholes just to augment but eventually we lost a large chunk of the farm because there was really no water …”.(I18)

5.4. The Cascading Effect of Infrastructure Disruption on Agrarian Livelihood Systems

5.4.1. Cascading effect of Floods

- Agricultural activities: In explaining how the damage to roads affected farming activities, farmers highlighted that, apart from the physical destruction of farmlands and crops, the loss of transport services made it almost impossible to transport inputs, such as fertilizers to farming communities, and crops from farm to market. This led to large amount of crop waste, particularly amongst perishable crops. Transport fares doubled and road damage alone accounted for about 50% of the crop waste. These are, however, estimates based on farmers’ responses, and not actual figures.

- Rural economic activities: Farmers also noted that the time of the disaster event coincided with the peak of the rainy season when farmers often moved food crops from barns to market in order to take advantage of the peak price periods, as more profits are made at such times. These difficulties contributed to the low returns on farmers’ investments, and in turn their income levels. Farmers explained that due to the loss of crops and low-income levels, the following farming sessions were affected, as they lacked the capacity for intense cultivation following huge losses from the previous year. Participants noted a general rise in the prices of goods, for both food crops and non-food items, around the study area after the event. This was attributed to the flood; however, it was difficult to separate the goods from areas genuinely affected from those taking advantage of the situation. Also, commercial activities and local revenue generation on market days were affected. The usual local tax collection and toll gate fares from traders and motorists on market days were low, thereby affecting the local economy.

- Human activities: respondents explained that losses from both crop damage due to the flood waters and crop waste due to transportation disruption caused psychological stress for large scale farmers. The livelihood sources of farmers without insurance were lost, which accounted for an increase in the poverty levels and a heightened food crisis. One respondent maintained that, due to the bridge collapse, there was also a temporary loss of leisure activities, as it was difficult to access the town center.

5.4.2. The Cascading Effect of Drought

- Agricultural activities: The impact of irrigation disruption on crop production can be summarized as ‘low water yields, poor crop yields’. Furthermore, planted seed and applied agrochemicals are wasted, whilst plant pests/diseases spread, and eventually there is a loss of operation. These add to the financial implications for farmers and the community as a whole.

- Rural economic activities: Farmers sometimes incur additional costs to sustain irrigation farming as they tend to spend more on labor to irrigate their crops. Farmers often spend more money to dig wells several meters deep to source for water and to fuel motorized pumps in order to irrigate crops. At other times, when the water crisis is severe and beyond farmers’ capacities, the authorities provide immediate alternatives, such as the construction of boreholes to minimize damage due to the harsh conditions. However, this is not the case at all times. At the end of the farming season, farmers sometimes record low returns on investment after spending huge sums of money to procure labor, and face the challenge of ‘middle men’, who largely determine the market prices of food crops. Although unstructured market prices are a deterrent to farmers, they are obliged to sustain production, which is still considered a 50 percent win.

- Human activities: Due to overcrowding and competition amongst various water users, there are cases of conflict, particularly between farmers and herdsmen, over the control of space and water. The destruction of crops and livestock, a loss of trust, the loss of livelihoods and eventual migration are noted as the results. Poor crop yields occur due to water scarcity alongside the destruction of crops and livestock due to conflicts, which tend to worsen the food crisis. In a bid to maintain law and order in crisis communities, a respondent explained that the local government is now compelled to redirect the limited funds meant for infrastructural development to maintain additional security services within the local government area. In their opinion, peace and security are top priorities over infrastructural development, as farmers need a clear environment to grow crops. Therefore, this is in agreement with the assertion of Al Khaili et al. (2013) that disasters can have a direct or indirect impact on the environment.

5.5. Implications for Farming Communities

5.6. Policy Implications

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| (A) Profile of Key Informants | Count (n = 12) | Percent (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administrative Level | Federal | 2 | 16.7 | |

| State | 4 | 33.3 | ||

| Local/Community | 8 | 76.7 | ||

| Background | Technical | 4 | 33.3 | |

| Planning | 6 | 50.0 | ||

| Mobilize/supervision | 4 | 33.3 | ||

| Gender (%) | Male | 10 | 83.3 | |

| Female | 2 | 16.7 | ||

| Years of experience (mean) | 18.6 | |||

| (B) Profile of Farmers Surveyed in Shendam & Riyom | Total (n = 175) | Shendam (n = 69) | Riyom (n = 106) | |

| Age groups (%) | 20–29 | 5.7 | 8.7 | 3.8 |

| 30–39 | 17.7 | 30.4 | 9.4 | |

| 40–49 | 37.1 | 30.4 | 41.5 | |

| 50> | 39.4 | 30.4 | 45.3 | |

| Gender (%) | Male | 70.3 | 91.3 | 56.6 |

| Female | 29.7 | 8.7 | 43.4 | |

| Education level (%) | Primary | 19.4 | 8.7 | 26.4 |

| Secondary | 28.6 | 43.5 | 18.9 | |

| Tertiary | 36.6 | 34.8 | 37.7 | |

| Informal | 15.4 | 13.0 | 17.0 | |

| Farming level (%) | Full time farmer | 56.6 | 39.1 | 67.9 |

| Part-time farmer | 43.4 | 60.9 | 32.1 | |

| Household size (mean) | 7.56 | 7.99 | 7.28 | |

| Farming Years (%) | <5 | 2.9 | 4.3 | 1.9 |

| 5–10 | 6.3 | 4.3 | 7.5 | |

| >10 | 90.9 | 91.3 | 90.6 | |

| Average monthly income (%) | <15,000 | 26.3 | 8.7 | 37.7 |

| 15,000–50,000 | 46.3 | 39.1 | 50.9 | |

| >50,000 | 27.4 | 52.2 | 11.3 | |

| Percentage of income from farming (%) | 25 | 29.1 | 4.3 | 45.3 |

| 50 | 22.3 | 27.5 | 18.9 | |

| 75 | 41.1 | 55.1 | 32.1 | |

| 100 | 7.4 | 13.0 | 3.8 | |

Appendix B

| List of Cascading effect of Agrarian Infrastructure Disruption | |

|---|---|

| Shendam | Riyom |

| Impacts of Climate-related events on Agrarian Infrastructure | |

| Impacts of floods on road network system | Impacts of drought on irrigation systems |

| -Washout of bridges and culverts -Washout of bridge and road embankments -Damage to road surfaces -Disruption of transport services | -Low water levels -Low yields of dams, boreholes and wells -Low water quality |

| Cascading effect on Agrarian Livelihoods | |

| Agriculture | |

| -Inability to access farms, communities and markets -High cost of transportation - High cost of inputs: fertilizer, seeds -Waste of food crops - Inability to meet demand -High loss and low profit -Loss of production due to infrastructure damage | -Poor crop yields -Waste of inputs: seeds and agrochemicals -Spread of plant pests and diseases -Loss of crops -Loss of production due to low water levels affecting irrigation infrastructure |

| Rural Economic Activities | |

| -Market instability and Price hike of goods -Low patronage of small scale industries: rice mills -Disruption of commercial activities due to supply chain disruption | -High cost of sourcing water -Cost of constructing alternative irrigation facilities -Less profit -Disruption of commercial activities due to inoperability |

| Human Activities | |

| -Loss of human lives -Loss of livelihoods -Human displacement/ temporary migration -Emotional and psychological effects -Increase in poverty levels -Food crisis -Disruption of social activities | -Overcrowding and competition on water sources -Strife and conflicts -Loss of trust -Loss of human lives -Loss of livelihoods -Human displacement -Increase in poverty levels -Food crisis -Pressure on authorities and security agencies |

References

- Abiodun, Babatunde J., Ayobami T. Salami, Olaniran J. Matthew, and Sola Odedokun. 2013a. Potential impacts of afforestation on climate change and extreme events in Nigeria. Climate Dynamics 41: 277–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiodun, Babatunde J., Kamoru A. Lawal, Ayobami T. Salami, and Abayomi A. Abatan. 2013b. Potential influences of global warming on future climate and extreme events in Nigeria. Regional Environmental Change 13: 477–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adakayi, Peter Eje, and Sunday Ishaya. 2016. Assessment of annual minimum temperature in some parts of northern Nigeria. Ethiopian Journal of Environmental Studies and Management 9: 220–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeagbo, Ademola, Adebukola Daramola, Adeola Carim-Sanni, Cajetan Akujobi, and Christiana Ukpong. 2016. Effects of natural disasters on social and economic well being: A study in Nigeria. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 17: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegbenle, Bukunmi O., and Adekunle A. Olatunji. 2017. Development of the Water Infrastructure in the Estuarine Part of Niger Delta to Ameliorate the Prevailing Transportation Problems. Global Journal of Research In Engineering 16: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Adegoke, Jimmy, Shrikant Jagtap, David Jimoh, Chinwe Ifejika, Julie Ukeje, and Anthony Anuforom. 2014. Nigeria’s Changing Climate: Risks, Impacts & Adaptation in the Agriculture Sector. Available online: https://boris.unibe.ch/62564/ (accessed on 25 October 2016).

- Adelekan, Ibidun O., and Adeniyi P. Asiyanbi. 2016. Flood risk perception in flood-affected communities in Lagos, Nigeria. Nature Hazards 80: 445–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesugba, Margaret Abiodun, and George Mavrotas. 2016. Youth Employment, Agricultural Transformation, and Rural Labor Dynamics in Nigeria. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). [Google Scholar]

- Adewuyi, Taiye Oluwafemi, and Emmanuel Ajayi Olofin. 2014. Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Flood Incidence in Nigeria and Its Implication for Land Degradation and Food Security. Journal of Agricultural Science 6: 150–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyinka, Stephen A., and Olugbamila Omotayo. 2015. Public private participation for infrastructure in developing countries. Academic Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 4: 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahungwa, Gabriel T., Ueda Haruna, and Rakiya Y. Abdusalam. 2014. Trend analysis of the contribution of agriculture to the gross domestic product of Nigeria (1960–2012). Journal of Agriculture and Veterinary Science 7: 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Akinsanola, Akintomide Afolayan, and Kehinde Olufunso Ogunjobi. 2014. Analysis of rainfall and temperature variability over Nigeria. Global Journal of Human Social Sciences: Geography & Environmental GeoSciences 14: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Akpodiogaga-a, Peter, and Ovuyovwiroye Odjugo. 2010. General overview of climate change impacts in Nigeria. Journal of Human Ecology 29: 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Khaili, Khalifa, Chaminda Pathirage, and Dilanthi Amaratunga. 2013. Building Disaster Resilience within the Emirati Energy Sector through a Comprehensive Strategic Mitigation Plan. Paper Presented at International Conference on Building Resilience, University of Huddersfield, UK, 17–19 September. [Google Scholar]

- Alcamo, Joseph, Norberto Fernandez, Sunday A. Leonard, Pascal Peduzzi, Ashbindu Singh, and Ruth Harding Rohr Reis. 2012. 21 Issues for the 21st Century: Results of the UNEP Foresight Process on Emerging Environmental Issues. Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Theodore L. 2015. Early Summer Rains and Their Mid-Summer Cessation Over the Caribbean: Dynamics, Predictability, and Applications. Ph.D. thesis, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Antle, John M. 1983. Infrastructure and aggregate agricultural productivity: International evidence. Economic Development and Cultural Change 31: 609–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, Peter J. 2002. Avoiding conflicts over Africa’s water resources. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment 31: 236–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audu, Bamaiyi E., Haruna O. Audu, Nankap L. Binbol, and Josiah N. Gana. 2013. Climate Change and its Implication on Agriculture in Nigeria. Abuja Journal of Geography and Development 3: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ayinde, Opeyemi E., Ajewole Oluwaferanmi O., Ogunlade Isreal, and Matthew O. Adewumi. 2010. Empirical Analysis of Agricultural Production and Climate Change: A Case Study of Nigeria. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa. 12: 275–83. [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger, Hans P., and Pierre Landell-Mills. 2016. The World Bank’s Strategy for Reducing Poverty and Hunger: A Report to the Development Community. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger, Hans P., Shahidur R. Khandker, and Mark R. Rosenzweig. 1993. How infrastructure and financial institutions affect agricultural output and investment in India. Journal of development Economics 41: 337–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, Ange-Benjamin, Tom Owiyo, and Youba Sokona. 2013. Loss and damage from the double blow of flood and drought in Mozambique. International Journal of Global Warming 5: 514–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappin, Emile J. L., and Telli van der Lei. 2014. Adaptation of interconnected infrastructures to climate change: A socio-technical systems perspective. Utilities Policy 31: 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuktu, Simi Sekyen. 2002. Dry Season Farming Around Yakubu Gowon Dam. Unpublished BSc Project, Geography and Planning. Jos: University of Jos. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, Peter. J. M., Dimes John P., Rao Poorna Chandra, Shapiro Barry I., Shiferaw Bekele, and Twomlow Steve J. 2008. Coping better with current climatic variability in the rain-fed farming systems of sub-Saharan Africa: An essential first step in adapting to future climate change? Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 126: 24–35. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Aiguo, and Tianbao Zhao. 2017. Uncertainties in historical changes and future projections of drought. Part I: Estimates of historical drought changes. Climatic Change 144: 519–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Richard. 2013. Floods in Nigeria. Floodlist- Reporting Floods and Flooding News Since 2008. Available online: http://floodlist.com/africa/floods-nigeria-september-2013 (accessed on 25 October 2016).

- Daze, Angie, Huong Vu L., Phuong Dang T., Yen Nguyen T., Dang Hanh M., Webb Julie, Gyang Romanus, Awuor Cynthia, Ambani Maureen, Razzetto Gabriela F., and et al. 2011. Understanding Vulnerability to Climate Change: Insights from Application of CARE’s Climate Vulnerability and Capacity Analysis (CVCA) Methodology. In CARE Poverty, Environment and Climate Change Network (PECCN). London: CARE. Available online: https://insights.careinternational.org.uk/publications/understanding-vulnerability-to-climate-change (accessed on 30 October 2016).

- Devereux, Stephen. 2007. The impact of droughts and floods on food security and policy options to alleviate negative effects. Agricultural Economics 37 S1: 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, Xinshen. 2016. Economic Importance of Agriculture for Sustainable Development and Poverty Reduction: Findings from a Case Study of Ghana. Global Forum on Agriculture, 29–30 November 2010. Policies for Agricultural Development, Poverty Reduction and Food Security. Paris: OECD Headquarters. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/agriculture/agricultural-policies/46341169.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2017).

- Dung-Gwom, John Y., Steve O. Hirse, and Pwat S. Pam. 2008. Four Year Strategic Plan for Urban Development and Housing in Plateau State (2008–2011); Jos: Plateau State Government.

- Ebele, Nebedum Ekene, and Nnaemeka Vincent Emodi. 2016. Climate Change and its Impact in Nigerian Economy. Journal of Scientific Reserach and Reports 10: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Effiom, Lionel, and Peter Ubi. 2016. Deficit, Decay and Deprioritization of Transport Infrastructure in Nigeria: Policy Options for Sustainability. International Journal of Economics and Finance 8: 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, Joshua, Delphine Deryng, Christoph Müller, Katja Frieler, Markus Konzmann, Dieter Gerten, Michael Glotter, Martina Flörke, Yoshihide Wada, and Neil Best. 2014. Constraints and potentials of future irrigation water availability on agricultural production under climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111: 3239–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eludoyin, Oyenike M., Ibidun O. Adelekan, Webster Richard, and Adebayo O. Eludoyin. 2014. Air temperature, relative humidity, climate regionalization and thermal comfort of Nigeria. International Journal of Climatology 34: 2000–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EM-DAT. 2017. The Emergency Events Database—Université catholique de Louvain (UCL)—CRED. Brussels: Guha-Sapir D. [Google Scholar]

- Enplan Group. 2004. Review of the Public Irrigation Sector in Nigeria. Abuja: Federal Ministry of Water Resources/UN Food and Agricultural Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Eruola, Abayomi, Niyi Bello, Gideon Ufeogbune, and Akeem Makinde. 2013. Effect of Climate Variability and Climate Change on Crop Production in Tropical Wet-and Dry Climate. Italian Journal of Agrometeorology-Rivista Italiana di Agrometeorologia 18: 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Falaki, A. A., Akangbe Jones Adebola, and Opeyemi Eyitayo Ayinde. 2013. Analysis of climate change and rural farmers’ perception in North Central Nigeria. Journal of Human Ecology 43: 133–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. 2016. The Agriculture Promotion Policy (2016–2020) Building on the Successes of the ATA, Closing Key Gaps. Abuja: FMARD. [Google Scholar]

- Fiki, Charles Oladipo, Joash Amupitan, Daniel Dabi, and Anthony Nyong. 2007. From disciplinary to interdisciplinary community development: The Jos-McMaster drought and rural water use project in Nigeria. Journal of Community Practice 15: 147–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuwape, Ibiyinka A., Samuel Toluwalope Ogunjo, Oluyamo Sunday S., and Rabiu A. B. 2016. Spatial variation of deterministic chaos in mean daily temperature and rainfall over Nigeria. Theoretical and Applied Climatology, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajigo, Ousman, and Alan Lukoma. 2011. Infrastructure and agricultural productivity in Africa. In African Development Bank Marketing Brief. Abidjan: AfDB. Available online: https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/Infrastructure%20and%20Agricultural%20Productivity%20in%20Africa%20FINAL.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2016).

- Garnett, Tara, Appleby Micheal C., Balmford Andrew, Bateman Ian J., Benton Tim G., Bloomer P., Burlingame Barbara, Dawkins Marian, Dolan Liam, and Fraser David. 2013. Sustainable intensification in agriculture: Premises and policies. Science 341: 33–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerland, Patrick, Adrian E. Raftery, Hana Ševčíková, Nan Li, Danan Gu, Thomas Spoorenberg, Leontine Alkema, Bailey K. Fosdick, Jennifer Chunn, and Nevena Lalic. 2014. World population stabilization unlikely this century. Science 346: 234–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghile, Yonas B., Taner Mehmet Ü., Brown Casey, Grijsen J. G., and Amal Talbi. 2014. Bottom-up climate risk assessment of infrastructure investment in the Niger River Basin. Climatic Change 122: 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, Dalila Cervantes, and Joe Dewbre. 2010. Economic Importance of Agriculture for Sustainable Development and Poverty Reduction: The Case Study of Vietnam. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/agriculture/agricultural-policies/46378758.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2016).

- Gommes, René A., and F. Petrassi. 1996. Rainfall variability and drought in sub-Saharan Africa. In SD Dimensions. Rome: FAO. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-au042e.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2017).

- Gongden, Japhet J., and Yilkur N. Lohdip. 2009. Climate Change and Dams Drying: A Case Study of Three Communities in Langtang South of Plateau State, Nigeria. African Journal of Natural Sciences 12: 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Goyol, Simi, and Chaminda Pathirage. 2017. Impacts of climate change on agrarian infrastructure and cascading effect on human and economic sustainability in Nigeria. Paper presented at International Conference on Climate Change and Sustainable Development in Africa (ICCCSDA), Sunyani, Ghana, 25–28 July. [Google Scholar]

- Goyol, Simi, Pathirage Chaminda, and Kulatunga Udayangani. 2017. Climate change risk on infrastructure and policy implications of appropriate mitigation measures in the Nigerian agricultural sector. Paper presented at 13th International Postgraduate Research Conference (IPGRC), University of Salford, UK, 14–15 September. [Google Scholar]

- Gutman, Jeffrey, Amadou Sy, and Soumya Chattopadhyay. 2015. Financing African Infrastructure: Can the World Deliver? South Dakota: Global Economy and Development Brookings. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/AGIFinancingAfricanInfrastructure_FinalWebv2.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2017).

- Hertel, Thomas W., and David B. Lobell. 2014. Agricultural adaptation to climate change in rich and poor countries: Current modeling practice and potential for empirical contributions. Energy Economics 46: 562–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifejika Speranza, Chinwe, Friday U. Ochege, Thaddeus C. Nzeadibe, and Agwu E. Agwu. 2018. Chapter 12—Agricultural Resilience to Climate Change in Anambra State, Southeastern Nigeria: Insights from Public Policy and Practice. In Beyond Agricultural Impacts. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 241–74. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R. Burke, and Anthony J. Onwuegbuzie. 2004. Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher 33: 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurukulasuriya, Pradeep, and Shane Rosenthal. 2013. Climate Change and Agriculture: A Review of Impacts and Adaptations. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/16616/787390WP0Clima0ure0377348B00PUBLIC0.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 25 October 2016).

- Maraseni, Tek Narayan, Mushtaq Shashbaz, and Kathryn Reardon-Smith. 2012. Climate change, water security and the need for integrated policy development: The case of on-farm infrastructure investment in the Australian irrigation sector. Environmental Research Letters 7: 034006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, John F. 2007. The impact of climate change on smallholder and subsistence agriculture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104: 19680–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Bureau for Statistics Nigeria. 2017. Nigerian Gross Domestic Product Report Quater 3 2017. In Nigwerian Domestic Product Report. Edited by Kale Yemi. Abuja: National Bureau of Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Nchuchuwe, Friday Francis, and Kehinde David Adejuwon. 2012. The challenges of agriculture and rural development in Africa: The case of Nigeria. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development 1: 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Nemry, Françoise, and Hande Demirel. 2012. Impacts of Climate Change on Transport: A focus on road and rail transport infrastructures. In European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC), Institute for Prospective Technological Studies (IPTS). Luxembourg: European Commission. Available online: ftp://s-jrcsvqpx101p.jrc.es/pub/EURdoc/JRC72217.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2016).

- Neumann, James E., Jason Price, Paul Chinowsky, Leonard Wright, Lindsay Ludwig, Richard Streeter, Russell Jones, Joel B. Smith, William Perkins, and Lesley Jantarasami. 2015. Climate change risks to US infrastructure: Impacts on roads, bridges, coastal development, and urban drainage. Climatic Change 131: 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Population Commission (NPC). 2006. Report of Nigeria’s National Population Commission on the 2006 Census. Abuja: National Population Commission Nigeria. [Google Scholar]

- Nyong, Anthony, Daniel Dabi, Adebowale Adepetu, Abou Berthe, and Vincent Ihemegbulem. 2008. Vulnerability in the sahelian zone of northern Nigeria: A household-level assessment, in Leary. In Climate Change and Vulnerability. London: Earthscan. [Google Scholar]

- Obadiah, Filibus V., A. J. Enejoh, Kojah Shola O., and Dadah Iyabode J. 2016. Status of Climate Change Adaptation of Rice and Yam Farmers in Shendam LGA, Plateau St. International Journal of Science and Applied Research 1: 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Odumodu, Lazarus Obi. 1983. Rainfall distribution, variability and probability in Plateau State, Nigeria. International Journal of Climatology 3: 385–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odunuga, Shakirudeen, and Gbolahan Badru. 2015. Landcover Change, Land Surface Temperature, Surface Albedo and Topography in the Plateau Region of North-Central Nigeria. Land 4: 300–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniran, Olajire J. 2002. Rainfall Anomalies in Nigeria: The Contemporary Understanding. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.734.1395&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 25 October 2016).

- Olaniran, Olajire J., and Graham N. Sumner. 1989. A study of climatic variability in Nigeria based on the onset, retreat, and length of the rainy season. International Journal of Climatology 9: 253–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniran, Olajire J., and Graham N. Sumner. 1990. Long-term variations of annual and growing season rainfalls in Nigeria. Theoretical and Applied Climatology 41: 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmstead, Sheila M. 2014. Climate change adaptation and water resource management: A review of the literature. Energy Economics 46: 500–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmstead, Sheila M., Karen A. Fisher-Vanden, and Renata Rimsaite. 2016. Climate change and water resources: Some adaptation tools and their limits. Jounal of Water Resources Planning and management 142: 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olomola, Aderibigbe, Tewodaj Mogues, Tolulope Olofinbiyi, Chinedum Nwoko, Edet Udoh, Reuben Alabi, Justice Onu, and Sileshi Woldeyohannes. 2014. Agriculture Public Expenditure Review at the Federal and Subnational Levels in Nigeria (2008–2012). Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/22345/Agriculture0pu0in0Nigeria0020080120.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 25 October 2016).

- Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J., R. Burke Johnson, and Kathleen M. T. Collins. 2009. Call for mixed analysis: A philosophical framework for combining qualitative and quantitative approaches. International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches 3: 114–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, Julie. 2016. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using IBM SPSS, 6th ed. Maidenhead: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Panteli, Mathaios, and Pierluigi Mancarella. 2015. Influence of extreme weather and climate change on the resilience of power systems: Impacts and possible mitigation strategies. Electric Power Systems Research 127: 259–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, Amrit. 2014. Infrastructure for Agriculture & Rural Development in India Need for a Comprehensive Program & Adequate Investment. Available online: http://www.microfinancegateway.org/sites/default/files/mfg-en-paper-infrastructure-for-agriculture-rural-development-in-india-need-for-a-comprehensive-program-adequate-investment-sep-2010.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2015).

- Pescaroli, Gianluca, and David Alexander. 2016. Critical infrastructure, panarchies and the vulnerability paths of cascading disasters. Natural Hazards 82: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinstrup-Andersen, Per, and Satoru Shimokawa. 2008. Rural Infrastructure and Agricultural Development. In Rethinking Infrastructure for Development. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Gina. 2014. Transport services and their impact on poverty and growth in rural sub-Saharan Africa: A review of recent research and future research needs. Transport Reviews 34: 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindap, Rose Manko. 2015. The Impact of Climate Change on Human Security in the Sahel Region of Africa. Donnish Journal of African Studies and Dev 1: 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rufus, Anthony, and Pre-ebi Bufumoh. 2017. Critical Infrastructure Decay and Development Crises in Nigeria. Global Journal of Human-Social Science Research 17: 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Salack, Seyni, Alessandra Giannini, Moussa Diakhaté, Amadou T. Gaye, and Bertrand Muller. 2014. Oceanic influence on the sub-seasonal to interannual timing and frequency of extreme dry spells over the West African Sahel. Climate Dynamics 42: 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlenker, Wolfram, and David B. Lobell. 2010. Robust negative impacts of climate change on African agriculture. Environmental Research Letters 5: 014010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sertoglu, Kamil, Sevin Ugural, and Festus Victor Bekun. 2017. The Contribution of Agricultural Sector on Economic Growth of Nigeria. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues 7: 547–52. [Google Scholar]

- Settele, Josef, Robert Scholes, Richard A. Betts, Stuart Bunn, Paul Leadley, Daniel Nepstad, Jonathan T. Overpeck, Miguel Angel Taboada, Andreas Fischlin, and José M. Moreno. 2015. Terrestrial and inland water systems. In Climate Change 2014 Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shenggen, Fan, and Xiaobo Zhang. 2004. Infrastructure and regional economic development in rural China. China Economic Review 15: 203–14. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, Susan. 2007. Climate Change 2007—The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Fourth Assessment Report of the IPCC. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Shikun, Pute Wu, Yubao Wang, Xining Zhao, Jing Liu, and Xiaohong Zhang. 2013. The impacts of interannual climate variability and agricultural inputs on water footprint of crop production in an irrigation district of China. Science of the Total Environment 444: 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshima, Hiroyuki. 2016. Understanding Irrigation System Diversity in Nigeria: A Modified Cluster Analysis Approach. Irrigation and Drainage 65: 601–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarhule, Augustine Aondover. 1997. Droughts, Rainfall and Rural Water Supply in Northern Nigeria. Hamilton: McMaster University. [Google Scholar]

- Tarhule, Augustine Aondover. 2007. Climate information for development: An integrated dissemination model. Africa Development 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teddlie, Charles, and Abbas Tashakkori. 2009. Foundations of Mixed Methods Research: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches in the Social and Behavioral Sciences. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, Robert. 2015. Ending Poverty and\Hunger by 2030: An Agender for the Global Food System. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. [Google Scholar]

- Udoka, Israel Sunday. 2013. The Imperatives of the Provision of Infrastructure and Improved Property Values in Nigeria. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 4: 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNISDR. 2004. Living with Risk: A Global Review of Disaster. New York: UN. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Geest, Kees, and Koko Warner. 2014. Loss and Damage from Droughts and Floods in Rural Africa1. In Digging Deeper: Inside Africa’s Agricultural, Food and Nutrition Dynamics. Edited by Akinyinka Akinyoade, Wijnand Klaver, Sebastiaan Soeters and Dick Foeken. Leiden: Brill, pp. 276–93. [Google Scholar]

- Van Vliet, Michelle T. H., Stefan Vögele, and Dirk Rübbelke. 2013. Water constraints on European power supply under climate change: Impacts on electricity prices. Environmental Research Letters 8: 035010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vliet, Michelle T. H., David Wiberg, Sylvain Leduc, and Keywan Riahi. 2016. Power-generation system vulnerability and adaptation to changes in climate and water resources. Nature Climate Change 6: 375–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatachalam, L. 2003. Infrastructure and Agricultural Development in Karnataka State. Nagarbhavi: Institute of Social and economic Change. Available online: http://www.isec.ac.in/AGRL%20DEVELOPMENT.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2016).

- Wapwera, Samuel Danjuma. 2014. Spatial Planning Framework for Urban Development and Management in Jos Metropolis Nigeria. Ph.D. thesis, University of Salford, Salford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Wharton, Clifton R. 1967. The Infrastructure for Agricultural Development. Edited by Agricultural Development and Economic Growth. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Xiaobo, and Shenggen Fan. 2004. How productive is infrastructure? A new approach and evidence from rural India. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 86: 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Impact level: H = High impact, M = Moderate impact, L = Low impact, VL = Very Low impact. |

| 2 | where Y is impact status (1 = impact, 0 = no impact). |

| Wharton (1967) | Patel (2014) |

|---|---|

| Capital Intensive: Irrigation, Roads, Bridges | Physical Infrastructure: Road connectivity, Transport, Storage, Processing, Preservation. |

| Resource based: Water/Irrigation, Farm power/Energy | |

| Capital Extensive: Extension Services | Input based: Seed, Fertilizer, Pesticides, Farm equipment, and Machinery. |

| Institutional: Formal & Informal institutions | Institutional Infrastructure: Agriculture research, Extension & Education Technology, Information & communication services, financial services, marketing |

| Event Type | Event Count | Total Deaths | Total Affected | Total Damage (′000 US$) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Droughts | 1 | 0 | 3,000,000 | 71,103 |

| Extreme Temperatures | 2 | 78 | - | - |

| Floods | 44 | 1493 | 10,478,919 | 644,522 |

| Storms | 6 | 254 | 17,012 | 2900 |

| Local Changes | Indicators | Percent (%) | Percentage Scores * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shendam | Riyom | |||

| Warm and Dry Patterns | Reduced stream flow | 100 | 10.0 * | 10.0 * |

| Rises in temperature | 97 | 9.1 * | 10.0 * | |

| Drying of wetlands | 89 | 8.3 | 9.3 * | |

| Longer dry periods | 87 | 8.3 | 9.1 * | |

| Prolonged dry spells | 83 | 7.8 | 8.7 | |

| Water shortages | 53 | 5.2 | 6.8 | |

| Rainy and Wet Patterns | Heavier rains | 100 | 10.0 * | 10.0 * |

| Destructive winds | 98 | 9.6 * | 10.0 * | |

| Irregular rains | 95 | 9.6 * | 9.5 * | |

| Less rain days | 92 | 9.1 * | 9.3 * | |

| Late onset of rains | 92 | 8.7 | 9.6 * | |

| Early cessation of rains | 89 | 8.7 | 9.1 * | |

| More floods | 78 | 10.0 * | 6.4 | |

| Destructive hail | 63 | 3.9 | 9.1 * | |

| Elements Affected | Climate Events/Impact Level 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Floods | Extreme Temperatures | Droughts | Storms | |

| Case 1: Agrarian Road in Shendam | ||||

| Road pavements | H | VL | VL | VL |

| Bridges | H | VL | VL | VL |

| Culverts | H | VL | VL | VL |

| Drainage | H | VL | VL | VL |

| Case 2: Irrigation Systems in Riyom | ||||

| Small earth dams/water catchment | VL | L | M | VL |

| Boreholes | VL | L | M | VL |

| Tube wells | VL | L | M | VL |

| Explanatory Variables | B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp (B) | 95% C.I. for EXP (B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Location | −22.77 | 4249.98 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.996 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Age | 2.58 | 0.79 | 10.79 | 1 | 0.001 | 13.24 | 2.84 | 61.82 |

| Gender | 0.37 | 0.53 | 0.48 | 1 | 0.490 | 1.44 | 0.51 | 4.06 |

| Education level | 1.04 | 0.61 | 2.95 | 1 | 0.086 | 2.83 | 0.86 | 9.26 |

| Farming years | 0.14 | 0.97 | 0.02 | 1 | 0.888 | 1.15 | 0.17 | 7.72 |

| Income level | −0.41 | 0.84 | 0.24 | 1 | 0.623 | 0.66 | 0.13 | 3.42 |

| Percentage of farm income | −2.05 | 0.57 | 13.12 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.39 |

| Constant | 20.96 | 4249.98 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.996 | 1,266,182,881.51 | ||

| Explanatory Variables | B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp (B) | 95% C.I. for EXP (B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Farming Season | 0.39 | 0.65 | 0.36 | 1 | 0.547 | 1.48 | 0.41 | 5.33 |

| Age | 2.31 | 0.77 | 8.99 | 1 | 0.003 | 10.03 | 2.22 | 45.25 |

| Gender | −0.95 | 0.54 | 3.10 | 1 | 0.078 | 0.39 | 0.14 | 1.11 |

| Education level | 0.58 | 0.66 | 0.78 | 1 | 0.377 | 1.79 | 0.49 | 6.51 |

| Farming years | −0.08 | 1.07 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.943 | 0.93 | 0.11 | 7.58 |

| Income level | −0.76 | 0.814 | 0.87 | 1 | 0.352 | 0.47 | 0.10 | 2.31 |

| Percentage of farm income | −1.16 | 0.60 | 3.77 | 1 | 0.053 | 0.31 | 0.10 | 1.01 |

| Constant | 0.41 | 1.61 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.800 | 1.51 | ||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goyol, S.; Pathirage, C. Farmers Perceptions of Climate Change Related Events in Shendam and Riyom, Nigeria. Economies 2018, 6, 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies6040070

Goyol S, Pathirage C. Farmers Perceptions of Climate Change Related Events in Shendam and Riyom, Nigeria. Economies. 2018; 6(4):70. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies6040070

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoyol, Simi, and Chaminda Pathirage. 2018. "Farmers Perceptions of Climate Change Related Events in Shendam and Riyom, Nigeria" Economies 6, no. 4: 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies6040070

APA StyleGoyol, S., & Pathirage, C. (2018). Farmers Perceptions of Climate Change Related Events in Shendam and Riyom, Nigeria. Economies, 6(4), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies6040070