A Firm-Level Investigation of Innovation in the Caribbean: A Comparison of Manufacturing and Service Firms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review of Literature

3. Research Methods

3.1. The Model

3.2. Variables

3.3. Data

4. Results

4.1. Probability of Innovation and Innovation Intensity

4.2. Innovation Output

4.3. Innovation Productivity

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Description | Equation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endogenous Variable | Equation (1) & Equation (2) | Equation (4) | Equation (5) | |

| d_INF | Firm reports any type of innovation activity Does this establishment have a department or a group of professionals dedicated to innovation (research and development, service); In the last three years, did this establishment introduce to the market a new or significantly improved good or service; In the last three years, did this establishment introduce improvements in marketing of its goods or services? | √ | ||

| lnINEM | Natural logarithm of firm’s total investment in innovation per average employee (between 2011 and 2012) | √ | √ | |

| d_INNOV | 1 if firm has introduced at least one product or process innovation in the last three years; 0 otherwise | √ | √ | |

| lnPROD | Increased firm’s performance per employee expressed in natural logarithms: sales per employee in 2012 less sales per employee in 2011 | √ | ||

| Continuous Independent Variables | ||||

| lnFIRM_AGE13 | Natural log of firms age at 2013, the previous year to which the survey taken | |||

| lnLABOR11 | Natural log of total labor force in 2011 | √ | ||

| lnLABOR12 | Natural log of total labor force in 2012 | √ | √ | |

| lnINEM_hat | Estimated value of expenditure on innovation per average employee (between 2011 and 2012) | √ | √ | |

| INNOV_hat | Estimated probability of introducing product or process innovation | √ | ||

| lnDSALES | Natural log of firm’s share of domestic sales (less indirect exports) in total sales | √ | √ | |

| lnESALES | Natural log of firm’s share of exports in total sales | √ | √ | |

| Binary Indicator Variables | ||||

| d_HFDI | 1 if firm reports more than 10% foreign ownership | √ | √ | |

| d_PAT_FILED | 1 if firm filed any patent application during the last 3 years (2011–2013); 0 otherwise | √ | ||

| d_PUB_FUND_U | 1 if firm accesses any type of public fund for innovation; 0 otherwise | √ | ||

| d_O_STRATEGY | 1 if firm reports any type of collaboration for innovation; 0 otherwise | √ | ||

| d_MKT_COMP | 1 if firm considers market competition very important/critical innovation; 0 otherwise | √ | ||

| d_TECH_BASED | 1 if firm is technologically driven entity, determined by the technology recruitment requirements of staff; 0 otherwise | √ | √ | |

| Categorical Variables | ||||

| OPTIONAL RESPONSES: No Obstacle (1); Minor Obstacle (2); Moderate Obstacle (3); Major Obstacle (4); Very Severe Obstacle (5) | ||||

| d_FCULTURE_OBS | Current organizational/managerial degree of self-confidence for innovation | √ | ||

| d_FINANCE_OBS | Level of available financial resources | √ | ||

| d_EMP_QTY_OBS | Qualification of employees | √ | ||

| d_PPOLICY_OBS | Copy right and patent protection against copycats | √ | ||

| d_MK_INFO_OBS | Level of information on new trends of the market | √ | √ | |

| d_TECH_INFO_OBS | Technical uncertainties; Level of information on available technologies | √ | √ | |

| d_FRM_OPEN_OBS | Compliance requirements to international standards | √ | ||

| d_OTHER_OBS | Other specified conditions reported as obstacles | √ | ||

| OPTIONAL RESPONSES: No Obstacle (1); Minor Obstacle (2); Moderate Obstacle (3); Major Obstacle (4); Very Severe Obstacle (5) | ||||

| d_ELECTRICITY; | Electricity level can affect the current operations | √ | ||

| d_TAX; | Tax rates can affect the current operations | √ | ||

| d_CRIME; | Crime, theft and disorder levels can affect the current operations | √ | ||

| d_FINANCE_COST; | Cost of finance (e.g., interest rates) can affect the current operations | √ | ||

| d_BUS_LICENCE | Business licensing and permits can affect the current operations | √ | ||

References

- Aghion, Philippe, Peter Howitt, and Susanne Prantl. 2015. Patent rights, product market reforms and innovation. Journal of Economic Growth 20: 223–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, Rita, and Ana Margarida Fernandes. 2008. Openness and technological innovations in developing countries: Evidence from firm-level surveys. Journal of Development Studies 44: 701–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibugi, Daniele, and Mario Pianta. 1996. Measuring technological change through patents and innovation surveys. Technovation 16: 451–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arundel, Anthony, Minna Kanerva, Adriana V. Cruysen, and Hugo Hollanders. 2007. Innovation Statistics for the European Service Sector. Maastricht: UNU-MERIT. [Google Scholar]

- Ayyagari, Meghana, Asli Demirguc-Kunt, and Vojislav Maksimovic. 2011. Firm innovation in emerging markets: The role of finance, governance, and competition. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 46: 1545–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becheikh, Nizar, Réjean Landry, and Nabil Amara. 2006. Lessons from innovation empirical studies in the manufacturing sector: A systematic review of the literature from 1993–2003. Technovation 28: 644–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogliacino, Francesco, Giulio Perani, Mario Pianta, and Stefano Supino. 2012. Innovation and development: The evidence from innovation surveys. Latin American Business Review 13: 219–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, Merrill. 1994. Tracking new products: A practitioner’s guide. Research Technology Management 37: 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Chung-Jen, and Jing-Wen Huang. 2009. Strategic human resource practices and innovation performance—the mediating role of knowledge management capacity. Journal of Business Research 62: 104–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, Jesper Lindgaard, and Ina Drejer. 2007. Blurring Boundaries between Manufacturing and Services. Report for the ServINNo Project: Service Innovation in the Nordic Countries: Key Factors for Policy Design. Aalborg: Aalborg University. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Wesley M. 1995. Fifty Years of Empirical Studies of Innovative Activity. Handbook of the Economics of Innovation and Technological Change. Edited by P. Stoneman. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 182–264. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Wesley M., and Daniel A. Levinthal. 1989. Innovation and learning: The two faces of R&D. The Economic Journal 99: 569–96. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs, R., P. Narandren, and A. Richards. 1996. A literature-based innovation output indicator. Research Policy 25: 403–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, Rene. 1990. The measurement of innovation performance in the firm: An overview. Research Policy 19: 185–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crépon, Bruno, Emmanuel Duguet, and Jacques Mairesse. 1998. Research, Innovation, and Productivity: An Econometric Analysis at the Firm Level. Economics of Innovation and New Technology 7: 115–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi, Gustavo, and Pluvia Zúñiga. 2012. Innovation and productivity: Evidence from six Latin American countries. World Development 40: 273–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi, Gustavo, Ezequiel Tacsir, and Fernando Vargas. 2014. Innovation and Productivity in Services. Empirical Evidence from Latin America. UNU-MERIT Working Papers 2014-068. Maastricht: United Nations University. [Google Scholar]

- Dabla-Norris, Era, Erasmus Kersting, and Geneviève Verdier. 2012. Firm productivity, innovation and financial development. Southern Economic Journal 79: 422–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desrochers, Pierre. 1998. On the abuse of patents as economic indicators. The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics 1: 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulude, Louise S. 1985. Patents as Indicators of the Invention; Ottawa: Statistics Canada, Science and Technology Division.

- Edison, Henry, Nauman bin Ali, and Richard Torkar. 2013. Towards innovation measurement in the software industry. Journal of Systems and Software 86: 1390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Elj, Moez. 2012. Innovation in Tunisia: Empirical analysis for industrial sector. Journal of Innovation Economics 9: 183–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Elj, Moez, and Boutheina Abassi. 2014. The determinants of innovation: An empirical analysis in Egypt, Jordan, Syria and Turkey. Canadian Journal of Development Studies 35: 560–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flor, Maria L., and Maria J. Oltra. 2004. Identification of innovating firms through technological innovation indicators: An application to the Spanish ceramic tile industry. Research Policy 33: 323–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, David A., and Jasjeet S. Sekhon. 2010. Endogeneity in probit response models. Political Analysis 18: 138–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fuentes, Claudia, Gabriela Dutrenit, Fernando Santiago, and Natalia Gras. 2015. Determinants of Innovation and Productivity in the Service Sector in Mexico. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 51: 578–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamal, Dalia, Tarek Sala, and Nesreen Elrayyes. 2011. How to Measure Organization Innovativeness: An Overview of Innovation Measurement Frameworks and Innovation Audit/Management Tools. Egypt: Technology Innovation and Entrepreneurship Center. [Google Scholar]

- Gallouj, Faiz, and Olivier Weinstein. 1997. Innovation in services. Research Policy 26: 537–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedhuys, Micheline. 2007. Learning, product innovation, and firm heterogeneity in developing countries: Evidence from Tanzania. Industrial and Corporate Change 16: 269–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman, James J. 1978. Dummy endogenous variables in a simultaneous equation system. Econometrica 47: 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HM Treasury. 2006. Budget 2006: A Strong and Strengthening Economy: Investing in Britain’s Future. London: The Stationery Office, p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Kleinknecht, Alfred, Kees van Montfort, and Erik Brouwer. 2002. The non-trivial choice between innovation indicators. Economics of Innovation and New Technology 11: 109–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiponen, Aija. 2005. Organization of knowledge and innovation: The case of Finnish business services. Industry and Innovation 12: 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, Mahreen, and Hamna Ahmed. 2011. What determines innovation in the manufacturing sector? Evidence from Pakistan. The Pakistan Development Review 50: 365–76. [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield, Edwin. 1985. How rapidly does new industrial technology leak out? The Journal of Industrial Economics 34: 217–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masso, Jaan, and Priit Vahter. 2011. The Link between Innovation and Productivity in Estonia’s Service Sectors. The Service Industries Journal 32: 2527–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, Ian. 2007. Research and development (R&D) beyond manufacturing: The strange case of services R&D. R&D Management 37: 249–68. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, Kevin X., and David Nordfors. 2006. Innovation Journalism, Competitiveness and Economic Development. Paper presented at The Third Conference on Innovation Journalism, Stanford, CA, USA, April 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, Juan Carlos, José Miguel Benavente, and Gustavo Crespi. 2016. The New Imperative of Innovation: Policy Perspectives for Latin America and the Caribbean. Washington: Inter-American Development Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. 2005. The Oslo Manual: Proposed Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Technological Innovation Data, 3rd ed. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. 2009. Measuring Innovation: A New Perspective. Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, Annika. 2008. Innovationsförmåga. Stockholm: Product Innovation Engineering Program (PIEp). [Google Scholar]

- Pamukcu, Teoman. 2003. Trade liberalization and innovation decisions of firms: Lessons from post-1980 Turkey. World Development 31: 1443–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmouni, Mohieddine, Mohamed Ayadi, and Murat Yildizoglu. 2010. Characteristics of innovating firms in Tunisia: The essential role of external knowledge sources. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 21: 181–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RTI International. 2005. Measuring Service-Sector Research and Development; U.S Department of Commerce. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/sites/default/files/documents/director/planning/report05-1.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2017).

- Rubalcaba, Luis. 2013. Innovation and the New Service Economy in Latin America and the Caribbean; Inter-American Development Bank. Available online: https://publications.iadb.org/bitstream/handle/11319/5747/Innovation%20and%20the%20New%20Service%20Economy%20in%20Latin%20America%20and%20the%20Caribbean.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 29 August 2017).

- Schumpeter, Joseph A. 1934. The Theory of Economic Development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schumpeter, Joseph A. 1942. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. New York: Harper Torchbooks. [Google Scholar]

- Sirilli, Giorgio, and Rinaldo Evangelista. 1998. Technological innovation in services and manufacturing: Results from Italian surveys. Research Policy 27: 881–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundbo, Jon. 1997. Management of innovation in services. Service Industries Journal 17: 432–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tether, Bruce, and Silvia Massini. 2007. Services and the Innovation Infrastructure. Innovation in Services; Occasional Paper No. 9. London: UK Department of Trade and Industry.

- Wallin Johanna, Andreas Larsson, Ola Isaksson, and Tobias Larsson. 2011. Measuring Innovation Capability―Assessing Collaborative Performance in Product-Service System Innovation. In Functional Thinking for Value Creation. Edited by J. Hesselbach and C. Herrmann. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, Bjorn M., and William E. Souder. 1997. Measuring R&D performance—State of the art. Research-Technology, Management 40: 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- WEF (World Economic Forum). 2015. Collaborative Innovation: Transforming Business, Driving Growth. Geneva: World Economic Forum. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Bo, and Xiao-lin Zhang. 2007. On Innovation in Service and Manufacturing Sector—Tendency and Integration. Paper presented at 2007 International Conference on Management Science and Engineering, Harbin, China, August 20–22. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Private Sector Development. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/node/679_hr (accessed on 29 August 2017). |

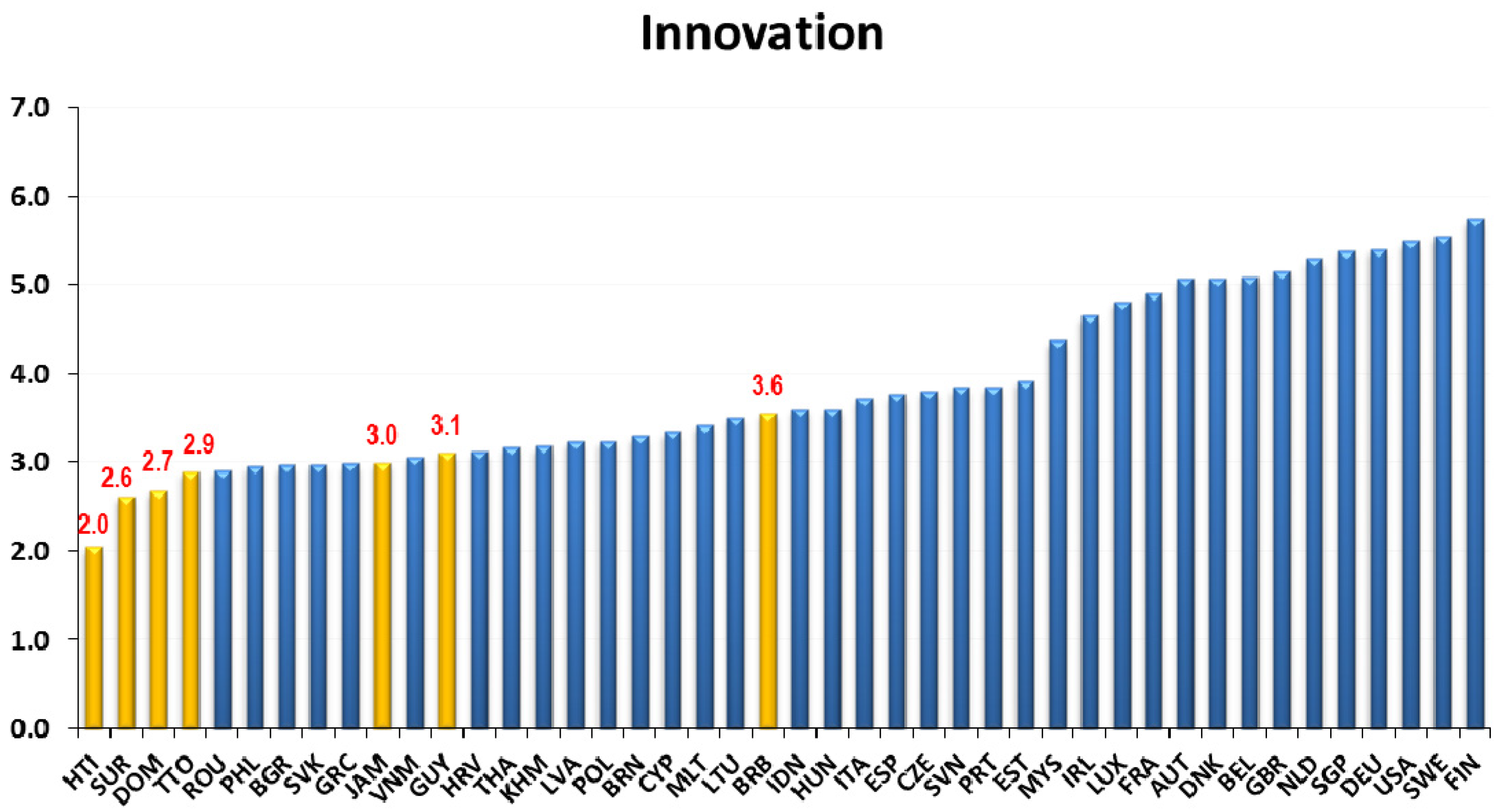

| 2 | The GCI innovation score for the Caribbean is based on the six members that are captured in the WEF reports between 2005 and 2015: Barbados, Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago. |

| 3 | Statistics collected from World Bank World Development Indicators online databank: https://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators. |

| 4 | Ibid. |

| 5 | Ibid. |

| 6 | In the literature, impediments to the innovation process have been categorised under four main classifications; i.e., cost related, institutional/organisational practices, market forces, and knowledge. |

| 7 | Despite arguments that likelihood estimation approaches are theoretically superior, Heckman (1978) suggested an unassuming two-step method for taking care of endogeneity, which works under noted conditions. This method has been applied to probit response models, recently by various researchers. According to Freedman and Sekhon (2010), significant numerical challenges are faced when trying to maximise the bi-probit likelihood function, as required under this study, even if the number of covariates is small. Heckman’s test under probit model assumptions can be suggested as a useful diagnostic. |

| 8 | Compete Caribbean is a program, jointly funded by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID) and the Government of Canada, that provides technical assistance grants and investment funding to support productive development policies, business climate reforms, clustering initiatives and Small and Medium Size Enterprise (SME) development activities in the Caribbean. |

| 9 | This study uses patent data as an innovation input. Frequently though, patent data is used as a measure of innovation output. However, its use as a measure of output is not unproblematic. Patents measure inventions rather than innovations (Coombs et al. 1996; Flor and Oltra 2004; OECD 2005). Measuring innovation using patent data risks overestimating the level of innovativeness by counting inventions that have not been transformed into marketable innovations (Becheikh et al. 2006). Further, many innovations are not patented, and some are covered by multiple patents (OECD 2005). For several reasons (for example, high costs or difficulties in patenting process), some firms prefer to protect their innovations by other methods such as maintaining lead time over rivals, industrial secrecy, and technological complexity (Archibugi and Pianta 1996; Mansfield 1985; Kleinknecht et al. 2002). Since not all innovations are patentable, and not all patentable innovations are patented (Dulude 1985), patent data is thus a very imprecise measure of innovation output (Becheikh et al. 2006). For a thorough survey of the problems with the use of patents to measure innovation activity, see Desrochers (1998). |

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barbados | 47 | 41 | 37 | _ |

| (40.5) | (40.8) | (42.5) | ||

| Dominican Republic | 79 | 83 | 89 | _ |

| (33.3) | (32.3) | (30.6) | ||

| Guyana | 78 | 80 | _ | _ |

| (34.4) | (32.5) | |||

| Jamaica | 82 | 82 | 96 | 89 |

| (32.9) | (32.4) | (29.9) | (29) | |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 81 | 90 | 80 | _ |

| (33.2) | (31.6) | (32.2) | ||

| No. of countries ranked in GII | 142 | 143 | 141 | 128 |

| Firm Type | ATG | BRB | BLZ | DOM | GRD | GUY | JAM | SLU | SKN | SVG | SUR | BAH | TTO | Freq. | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing | |||||||||||||||

| Food | 8 | 14 | 22 | 13 | 11 | 17 | 26 | 2 | 5 | 21 | 19 | 16 | 22 | 196 | 10 |

| Textiles | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0.3 |

| Garments | 1 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 10 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 41 | 2.1 |

| Chemicals | 2 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 15 | 51 | 2.6 |

| Plastics and rubber | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 18 | 0.9 |

| Non-metallic mineral products | 1 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 14 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 49 | 2.5 |

| Basic metals | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 27 | 1.4 |

| Fabricated metal products | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 11 | 35 | 1.8 |

| Machinery and equipment | 8 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 45 | 2.3 |

| Electronics | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 18 | 0.9 |

| Other manufacturing | 1 | 17 | 23 | 0 | 2 | 15 | 40 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 32 | 0 | 35 | 174 | 8.9 |

| Services | |||||||||||||||

| Construction | 9 | 6 | 3 | 10 | 16 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 16 | 8 | 7 | 23 | 26 | 136 | 6.9 |

| Services of motor vehicles | 7 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 11 | 4 | 21 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 14 | 78 | 4 |

| Wholesale | 1 | 7 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 13 | 12 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 26 | 95 | 4.8 |

| Retail | 38 | 9 | 18 | 20 | 35 | 37 | 71 | 28 | 30 | 38 | 14 | 21 | 107 | 466 | 23.7 |

| Hotel and restaurants | 35 | 32 | 31 | 39 | 34 | 10 | 18 | 32 | 27 | 17 | 8 | 30 | 26 | 339 | 17.2 |

| Transport | 13 | 8 | 8 | 23 | 7 | 3 | 13 | 5 | 12 | 15 | 16 | 10 | 21 | 154 | 7.8 |

| Information technology | 2 | 6 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 38 | 1.9 |

| Indicator | 2013/14 | Indicator | 2013/14 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labor and Skills | Mnu | Srv | Financing | Mnu | Srv |

| Number of permanent full-time workers | 63.0 | 52.0 | Currently have a line of credit or loan from a financial institution | 42.6 | 37.9 |

| Number of temporary workers | 6.0 | 4.0 | Proportion of working capital financed internally (%) | 58.4 | 59.6 |

| Percent of firms offering formal training (%) | 56.5 | 56.4 | Proportion of working capital financed by banks (%) | 16.5 | 15.0 |

| Percent of firms identifying an inadequately educated workforce as a major constraint (%) | 59.1 | 86.4 | Proportion of working capital financed by supplier credit (%) | 16.7 | 18.4 |

| Percent of firms identifying labor regulations as a major constraint (%) | 36.7 | 17.3 | Proportion of working capital financed by Government (%) | 3.4 | 2.9 |

| Legal Status | Business Environment Obstacles | ||||

| Shareholding company (%) | 40.9 | 34.0 | Tax rates (%) | 55.0 | 79.5 |

| Sole proprietorship (%) | 30.8 | 39.6 | Access to Finance (%) | 55.2 | 88.1 |

| Partnership (including limited liability (%) | 14.1 | 12.3 | Cost of Finance (%) | 55.9 | 79.1 |

| Limited partnership (%) | 13.6 | 13.9 | Macroeconomic Conditions (%) | 48.9 | 77.9 |

| Other (%) | 0.6 | 0.2 | Customs and Trade Regulations (%) | 46.7 | 79.7 |

| Proportion of private domestic ownership in a firm (%) | 88.1 | 88.0 | Political Environment (%) | 42.7 | 71.0 |

| Proportion of private foreign ownership in a firm (%) | 11.0 | 11.2 | Inadequately Educated Workforce (%) | 59.1 | 86.4 |

| Proportion of government/state ownership in a firm (%) | 0.6 | 0.6 | Electricity (%) | 48.8 | 76.3 |

| Gender Composition of Management | Practices of the Informal Sector (%) | 49.4 | 79.9 | ||

| All men (%) | 23.8 | 22.1 | Tax Administration (%) | 45.3 | 75.8 |

| Predominantly men (%) | 43.3 | 40.0 | Transportation (%) | 37.7 | 66.4 |

| Equally men and women (%) | 17.4 | 17.8 | Crime, Theft and Disorder (%) | 50.6 | 85.4 |

| Predominantly women (%) | 10.0 | 12.8 | Business Strategy—Goals for past 2 years. | ||

| All women (%) | 5.2 | 7.4 | To obtain quality certification (%) | 21.4 | 22.1 |

| Sales, Foreign Trade Competition | To support innovation (%) | 27.6 | 11.7 | ||

| Portion of firms with internationally Recognized Quality Certification (%) | 25.3 | 21.6 | To promote exports (%) | 17.3 | 15.2 |

| National Sales (%) | 88.3 | 93.1 | To improve quality of good or services (%) | 28.6 | 8.1 |

| Direct Exports (%) | 11.7 | 6.9 | To develop new foreign markets (%) | 11.8 | 12.7 |

| Primary Destination for Direct Exports (%) | USA | USA | To reduce energy consumption (%) | 30.3 | 27.8 |

| Material Inputs or supplies of foreign origin (% of sales) | 36.2 | 43.0 | To increase the number of goods or services offered (%) | 31.8 | 17.7 |

| Independent Variables | Probability of Innovation Per Employee | Innovation Intensity Per Employee | Innovation Output | Innovation Productivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (d_INF—Equation (1)) | (lnINEM—Equation (2)) | (d_INNOV—Equation (4)) | (lnPROD—Equation (5)) | |

| lnLABOR11 | 0.607 *** | |||

| (0.127) | ||||

| lnDSALES | 0.222 *** | 0.748 *** | ||

| (0.05) | (0.196) | |||

| lnESALES | ||||

| d_O_STRATEGY | −1.553 *** | |||

| (0.258) | ||||

| d_TECH_BASED | 0.346 * | |||

| (0.18) | ||||

| d_HFDI | 0.427 ** | |||

| (0.217) | ||||

| d_PAT_FILED | 12.02 *** | |||

| (0.027) | ||||

| lnLABOR12 | 0.664 *** | |||

| (0.119) | ||||

| lnINEM_hat | −3.419 *** | 1.218 *** | ||

| (0.87) | (0.2) | |||

| d_FCULTURE_OBS | ||||

| d_TECH_INFO_OBS | −0.168 ** | |||

| (0.084) | ||||

| d_MK_INFO_OBS | −0.202 *** | |||

| (0.077) | ||||

| d_FRM_OPEN_OBS | ||||

| d_OTHER_OBS | 0.029 *** | |||

| (0.005) | ||||

| d_INNOV(est.) | 2.15 *** | |||

| (0.385) | ||||

| lnFIRM_AGE13 | −0.137 *** | |||

| (0.077) | ||||

| d_FINANCE_COST | 0.141 ** | |||

| (0.056) | ||||

| d_BUS_LICENCE | 0.114 ** | |||

| (0.048) | ||||

| d_ELECTRICITY | ||||

| d_TAX | ||||

| d_CRIME | ||||

| _cons | −6.142 *** | 5.742 *** | 18.83 *** | |

| (0.057) | (0.793) | (4.980) | ||

| Observations | 537 | 537 | 591 | 591 |

| Independent Variables | Probability of Innovation Per Employee | Innovation Intensity Per Employee | Innovation Output | Innovation Productivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (d_INF—Equation (1)) | (lnINEM—Equation (2)) | (d_INNOV—Equation (4)) | (lnPROD—Equation (5)) | |

| lnLABOR11 | 0.028 * | −0.383 ** | ||

| (0.016) | (0.16) | |||

| lnDSALES | −0.011 *** | 0.331 *** | 1.057 *** | |

| (0.004) | (0.105) | (0.403) | ||

| lnESALES | 0.072 *** | 0.24 *** | ||

| (0.025) | (0.087) | |||

| d_O_STRATEGY | −1.765 *** | |||

| (0.484) | ||||

| d_TECH_BASED | 0.815 * | 2.472 *** | −0.720 *** | |

| (0.434) | (0.989) | (0.139) | ||

| d_HFDI | 0.069 * | |||

| (0.041) | ||||

| d_PAT_FILED | 12.000 *** | |||

| (2.38) | ||||

| lnLABOR12 | −1.063 *** | 0.710 *** | ||

| (0.47) | (0.036) | |||

| lnINEM_hat | −3.184 *** | 1.207 *** | ||

| (1.22) | (0.108) | |||

| d_FCULTURE_OBS | −0.128 * | |||

| (0.02) | ||||

| d_TECH_INFO_OBS | −0.127 * | |||

| (0.067) | ||||

| d_MK_INFO_OBS | −0.13 * | |||

| (0.0691) | ||||

| d_FRM_OPEN_OBS | −0.177 *** | |||

| (0.063) | ||||

| d_OTHER_OBS | 0.031 *** | |||

| (0.003) | ||||

| d_INNOV(est.) | 2.68 *** | |||

| (0.196) | ||||

| lnFIRM_AGE13 | 0.156 *** | |||

| (0.093) | ||||

| d_FINANCE_COST; | ||||

| d_BUS_LICENCE | ||||

| d_ELECTRICITY | 0.093 *** | |||

| (0.033) | ||||

| d_TAX | 0.089 *** | |||

| (0.034) | ||||

| d_CRIME | 0.124 *** | |||

| (0.036) | ||||

| _cons | −6.223 *** | 5.575 *** | 17.57 *** | |

| (1.135) | (1.681) | (6.815) | ||

| Observations | 1207 | 1207 | 1175 | 1173 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alleyne, A.; Lorde, T.; Weekes, Q. A Firm-Level Investigation of Innovation in the Caribbean: A Comparison of Manufacturing and Service Firms. Economies 2017, 5, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies5030034

Alleyne A, Lorde T, Weekes Q. A Firm-Level Investigation of Innovation in the Caribbean: A Comparison of Manufacturing and Service Firms. Economies. 2017; 5(3):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies5030034

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlleyne, Antonio, Troy Lorde, and Quinn Weekes. 2017. "A Firm-Level Investigation of Innovation in the Caribbean: A Comparison of Manufacturing and Service Firms" Economies 5, no. 3: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies5030034

APA StyleAlleyne, A., Lorde, T., & Weekes, Q. (2017). A Firm-Level Investigation of Innovation in the Caribbean: A Comparison of Manufacturing and Service Firms. Economies, 5(3), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies5030034