1. Introduction

Natural rubber is a strategic commodity for automotive production, medical equipment, and industrial manufacturing, while serving as a critical source of income for rural households in Thailand—the world’s largest exporter. Yet rubber prices remain persistently volatile, driven by fluctuations in global demand, energy and freight costs, speculative activity on Asian futures exchanges, exchange-rate movements, and periodic policy interventions. For an export-dependent sector governed by an export-parity pricing mechanism, such volatility raises a central policy concern: how international price signals are filtered, transformed, and ultimately transmitted to domestic producers. Understanding this transmission process is therefore essential for designing effective stabilization, risk-management, and income-support policies.

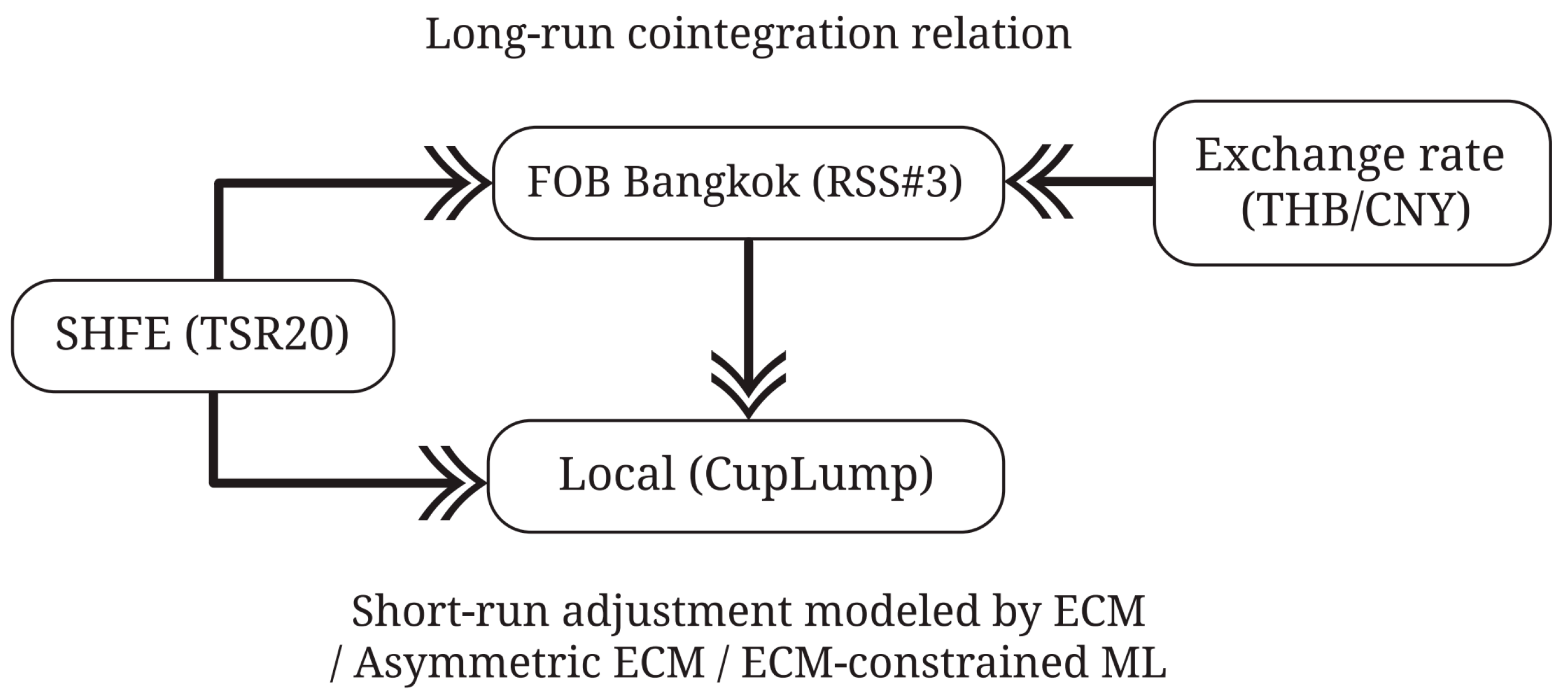

In recent years, the Shanghai Futures Exchange (SHFE) has emerged as the dominant benchmark for natural rubber pricing in Asia. However, its influence on Thailand’s domestic markets is not direct. Rather than acting as an immediate price-setting mechanism, SHFE futures primarily serve as an upstream information signal that is incorporated into export quotations. Global price information flows through a hierarchical structure in which FOB Bangkok functions as the operative price-setting node, converting international benchmarks into export prices denominated in Thai baht. Domestic farm-gate prices adjust only after further filtering through exchange-rate movements, logistics costs, grading systems, and procurement practices. This multi-stage, cross-currency transmission chain implies that price pass-through may be incomplete, delayed, and structurally asymmetric, even when long-run integration is preserved.

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework of the SHFE–FOB–LOCAL price transmission chain examined in this study.

Despite extensive research on horizontal linkages among futures markets such as SHFE, TOCOM, and SGX, the full vertical transmission mechanism linking SHFE → FOB → local farm-gate prices has not been examined within a unified empirical framework.

Existing studies typically focus on isolated segments—either global-to-export integration or export-to-domestic pricing—without explicitly modeling how futures-market signals are filtered through export pricing before reaching producers. As a result, current evidence provides limited insight into how asymmetric adjustment, nonlinear short-run dynamics, and post-2020 market changes interact within the complete price-transmission chain of Thailand’s rubber sector.

This study advances the literature in three important ways. First, it provides the first integrated empirical analysis of the entire SHFE–FOB–LOCAL transmission chain, explicitly modeling the hierarchical structure through which international price signals reach domestic markets. Second, it jointly estimates symmetric and asymmetric error-correction dynamics to test whether positive and negative export-price shocks propagate differently along the chain, thereby identifying the direction and magnitude of short-run adjustment asymmetries. Third, it introduces an ECM-constrained gradient-boosting model as a diagnostic tool for nonlinear dynamics, embedding machine learning within a validated equilibrium structure rather than treating it as a stand-alone forecasting device.

Operationally, the empirical strategy combines three elements: (i) Engle–Granger cointegration is used to establish the long-run equilibrium linking SHFE futures prices, FOB Bangkok quotations, the THB/CNY exchange rate, and domestic farm-gate prices; (ii) symmetric and asymmetric error-correction models quantify short-run adjustments and test for differential responses to positive versus negative export-price shocks; and (iii) an ECM-constrained gradient-boosting model preserves the estimated long-run relationship while allowing for flexible nonlinear interactions in short-run dynamics.

Using harmonized weekly data on SHFE futures (CNY), FOB Bangkok RSS#3 quotations (THB), the THB/CNY exchange rate, and farm-gate unsmoked rubber-sheet prices, the analysis yields three key findings. First, a stable long-run equilibrium links the four series, with FOB emerging as the dominant transmission channel and the exchange rate acting as a long-run anchor. Once FOB and FX are controlled for, SHFE does not exert a direct long-run influence on domestic prices, confirming that futures-market signals are transmitted indirectly through the export node. Second, short-run responses are strongly asymmetric: positive FOB shocks are transmitted almost one-for-one to domestic prices, whereas negative shocks have only a limited effect. Third, the machine-learning extension does not outperform the linear ECM in out-of-sample forecasting, indicating that once long-run equilibrium conditions are imposed, short-run price adjustment is predominantly linear.

By jointly modeling long-run integration, short-run asymmetry, and nonlinear robustness within a single coherent framework, this study provides new evidence on the functioning of Thailand’s rubber price system. The results underscore the central role of export pricing in shaping domestic price dynamics and have direct implications for stabilization policies, exchange-rate risk management, and the design of market-based instruments aimed at reducing income volatility among smallholder producers.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Global Rubber Markets and Futures Integration

Research on price transmission has long examined how shocks in upstream markets propagate through vertically linked commodity chains. Under the Law of One Price, identical goods should sell for the same price once transport and transaction costs are accounted for. In practice, however, markets are imperfect and commodity price series are typically non-stationary.

Engle and Granger (

1987) demonstrate that such series may share a stationary linear combination, defining a long-run equilibrium toward which short-run deviations are systematically corrected over time.

Johansen (

1991) extends this framework to multivariate systems, allowing for the identification of multiple cointegrating relationships. Subsequent work, notably

Fackler and Goodwin (

2001), establishes cointegration and error-correction models as the standard empirical tools for analyzing spatial and vertical market integration in agricultural and commodity markets.

2.2. Asymmetric Price Transmission and Adjustment Dynamics

Beyond long-run integration, a substantial body of literature emphasizes that price transmission is frequently asymmetric, with adjustment paths differing for positive and negative shocks.

Meyer and von Cramon-Taubadel (

2004) document widespread asymmetry, showing that downstream prices often adjust more rapidly to increases than to decreases in upstream prices.

von Cramon-Taubadel and Loy (

1996) introduce asymmetric ECMs that explicitly separate positive and negative shocks, while

Shin et al. (

2014) develop the NARDL framework to allow for both short- and long-run asymmetries within a nonlinear setting. Empirical studies attribute asymmetric adjustment to market power, contracting frictions, inventory behavior, and regulatory rigidities. Recent evidence further links asymmetric price adjustment to international price transmission and exchange-rate movements, as shown by

Tabash et al. (

2024), who document symmetry and asymmetry patterns in international markets under different adjustment regimes. These mechanisms are particularly relevant for natural rubber, where intermediaries may respond differently to favorable and unfavorable international price movements, shaping the distribution of price risk along the supply chain.

2.3. Exchange-Rate Effects and Vertical Transmission in Natural Rubber

In export-oriented commodity systems, exchange rates play a central role in mediating international price signals. Empirical studies on natural rubber confirm strong long-run linkages between global benchmarks, export prices, and domestic markets, but reveal mixed short-run dynamics.

Srisuksai (

2020) and

Khongrit (

2017) find cointegration among Thai domestic prices, FOB Bangkok quotations, and international benchmarks, with tight integration at the export level but weaker and slower transmission to farm-gate prices.

Burger et al. (

2002) highlight the importance of exchange-rate volatility in shaping rubber price discovery, while

Wanaset and Jatuporn (

2020) show delayed domestic responses despite long-run cointegration.

Ahoba and Gaspart (

2019) document downward-biased transmission in Côte d’Ivoire, illustrating how international shocks can be unevenly absorbed across market levels. Taken together, this literature points to a hierarchical transmission structure in natural rubber markets, though the complete SHFE → FOB → LOCAL chain for Thailand has not been examined within a unified econometric framework.

2.4. Machine Learning and Hybrid Econometric Approaches

While traditional econometric models—such as VECM, ARDL, and NARDL—remain the workhorses of price-transmission analysis, recent studies explore whether machine-learning methods can capture nonlinear dynamics beyond linear or piecewise-linear adjustment.

Mallory et al. (

2025) show that hybrid ML–time-series models can enhance forecasting performance in agricultural price-transmission settings, while

Barbaglia et al. (

2022) uncover latent interdependencies across commodity markets using data-driven techniques.

Wen et al. (

2019) demonstrate that LSTM networks can capture complex temporal patterns in financial and commodity prices. However, purely data-driven approaches may sacrifice economic interpretability and risk ignoring equilibrium restrictions that govern commodity price systems. Hybrid frameworks that explicitly impose cointegration or error-correction structure—such as ECM-constrained gradient boosting—offer a practical compromise by preserving long-run economic discipline while allowing flexible short-run dynamics. Applications of such hybrid approaches to natural rubber markets, however, remain limited.

2.5. Synthesis and Research Gap

Three key insights emerge from the literature. First, international and domestic commodity prices are frequently cointegrated, and natural rubber is no exception, yet the vertical SHFE–FOB–LOCAL transmission chain has not been formally modeled within a single equilibrium-consistent framework. Second, short-run price transmission is often partial, delayed, and asymmetric, but asymmetric ECMs have rarely been applied to Thailand’s rubber market. Third, hybrid econometric–machine-learning approaches provide a promising way to assess nonlinear dynamics without discarding structural discipline, but their use in natural rubber price analysis remains scarce.

Methodologically, prior research supports a structured sequence consisting of unit-root and cointegration tests, followed by symmetric and asymmetric error-correction models, and complemented by machine-learning-based diagnostics to assess potential nonlinearities. From a policy perspective, Thai rubber prices are structurally anchored to global benchmarks and exchange-rate movements through an export-parity pricing mechanism (

Burger et al., 2002). Effective stabilization strategies must therefore align with these structural linkages, relying on rule-based buffer-stock schemes, benchmark-linked hedging instruments, and targeted interventions informed by asymmetric transmission patterns. A framework that jointly quantifies linear adjustment, asymmetric pass-through, and potential nonlinear dynamics along the SHFE–FOB–LOCAL chain is thus essential for designing durable and economically coherent policies.

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data and Variables

The empirical analysis examines the SHFE → FOB Bangkok → Local farm-gate price transmission chain using a harmonized weekly dataset covering January 2015 to the second week of November 2025 (555 observations). Four variables are used:

- (1)

SHFE rubber futures , representing upstream financial-market signals;

- (2)

Rubber-smoked sheet No. 3 (RSS#3) FOB Bangkok export quotations , the primary export-level benchmark;

- (3)

Thai domestic farm-gate prices for unsmoked rubber sheet (raw sheet rubber purchased directly from smallholders); and

- (4)

The THB/CNY exchange rate .

All variables are transformed into natural logarithms:

and short-run dynamics are modeled using first differences:

A balanced dataset is obtained after removing missing values.

3.2. Sample Period, Data Coverage, and Train-Test Split

The full sample contains 555 weekly observations (2015–2025). For the machine-learning component, the dataset is partitioned chronologically to preserve the temporal structure of the price process:

This forward-looking split follows standard practice in time-series ML and ensures that the evaluation reflects genuine out-of-sample performance rather than randomized resampling. The descriptive statistics indicate substantial co-movement among SHFE, FOB, and LOCAL prices, while the FX series exhibits independent variation that influences local-currency pass-through (

Table 1).

3.3. Unit Root and Cointegration Tests

Augmented Dickey–Fuller tests indicate that all log-level price and exchange-rate series are non-stationary, while first differences are stationary. All variables are therefore .

Long-run relations are assessed using the Engle–Granger approach:

An ADF test applied to the residuals rejects the unit-root null, confirming a stable long-run equilibrium among the four variables. The estimated residual

serves as the disequilibrium term in subsequent dynamic models. As shown in

Table 2, all series are non-stationary in levels but stationary in first differences.

3.4. Two-Step Error-Correction Model (Speed of Adjustment)

The adjustment speed is estimated using the Engle–Granger two-step ECM to avoid multicollinearity between

and contemporaneous differenced regressors:

The coefficient measures the proportion of the long-run disequilibrium corrected each week and indicates how quickly domestic prices converge back to the SHFE–FOB–FX–LOCAL parity.

3.5. Short-Run and Asymmetric ECM with ML Extension

Short-run transmission is modeled without the ECT:

Asymmetric effects are examined by decomposing export-price shocks into positive and negative components:

and estimating:

An F-test of evaluates whether increases and decreases in FOB prices propagate differently to domestic markets.

To assess potential nonlinearities, an ECM-constrained gradient boosting model is estimated:

using the feature vector:

Because the ML specification incorporates the validated equilibrium structure, differences in predictive performance relative to the linear ECM reveal whether nonlinear dynamics meaningfully contribute to short-run adjustment. Gradient boosting is chosen over more complex architectures such as LSTM networks for two reasons. First, GBM can flexibly approximate nonlinear interactions and threshold effects while remaining relatively transparent in terms of variable importance and partial effects, which is crucial for economic interpretation. Second, at the weekly frequency considered here, the primary concern is not capturing very high-frequency temporal memory, but testing whether deviations from the linear ECM structure materially improve predictive performance. Accordingly, the GBM is treated as a structurally constrained diagnostic tool: it is fed exactly the same information set as the ECM, including the error-correction term, so that any performance gains can be interpreted as evidence of nonlinear adjustment mechanisms rather than differences in model inputs. In this sense, the ML extension is designed as a robustness and validation device for the ECM, not as a black-box replacement for the underlying economic model.

Importantly, the machine-learning component in this study is not intended as a black-box forecasting alternative to the econometric model. Instead, it is explicitly designed as a diagnostic and robustness check for the linear error-correction framework. By constraining the gradient boosting model to the same information set as the ECM—including the error-correction term—any differences in predictive performance can be attributed to nonlinear short-run dynamics rather than to differences in model structure or data inputs.

More complex architectures such as LSTM networks are deliberately not employed for three reasons. First, the available sample size at the weekly frequency (555 observations) limits the reliable estimation of high-parameter deep learning models. Second, LSTM models offer limited economic interpretability, making it difficult to relate results to equilibrium adjustment and price-transmission mechanisms. Third, the objective of the analysis is not to capture long-memory or ultra-high-frequency dynamics, but to test whether deviations from a linear ECM materially improve explanatory or predictive performance once long-run equilibrium conditions are imposed.

Accordingly, the machine-learning extension serves as a validation device: if the constrained ML model fails to outperform the ECM, this provides evidence that the price-transmission process is adequately characterized by equilibrium-based linear adjustment rather than by economically meaningful nonlinear regimes.

3.6. Empirical Strategy

The analysis follows a structured workflow:

- (1)

Test for unit roots and determine the integration order.

- (2)

Estimate the Engle–Granger long-run relationship and confirm cointegration.

- (3)

Estimate the two-step ECM to identify the speed-of-adjustment parameter .

- (4)

Estimate symmetric and asymmetric short-run transmission models using differenced regressors.

- (5)

Estimate an ECM-constrained gradient boosting model and compare its predictive accuracy and feature-importance profile with the linear ECM.

This integrated econometric–ML framework provides a coherent assessment of long-run anchoring, short-run pass-through, asymmetry, and potential nonlinearities in the SHFE–FOB–LOCAL price transmission.

SHFE futures, FOB Bangkok quotations, and the exchange rate jointly determine the long-run equilibrium level of the domestic rubber price. Short-run adjustments towards this equilibrium and potential asymmetries are modeled using linear ECMs and an ECM-constrained machine learning specification.

4. Results

This section reports the empirical results in a structured manner, focusing on stationarity, long-run relationships, adjustment dynamics, short-run transmission, and the performance of the machine-learning extension.

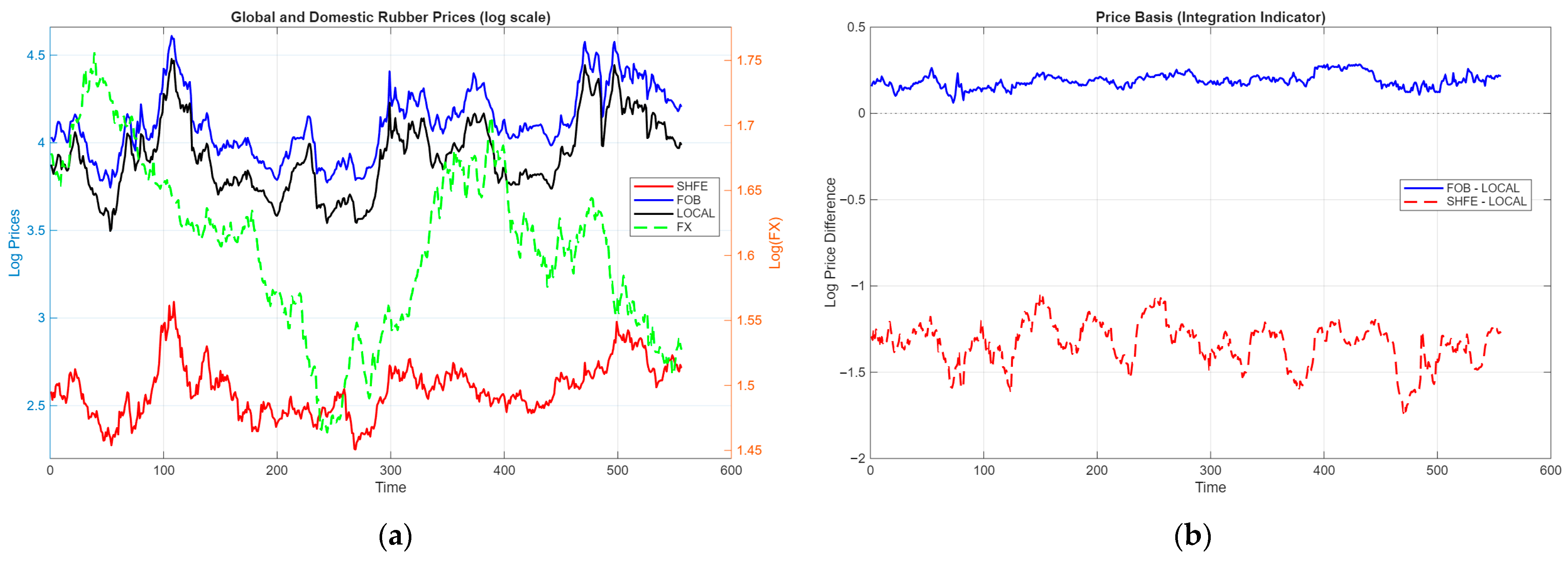

4.1. Stationarity and Integration

Unit-root diagnostics indicate a standard integrated structure for all variables in the SHFE–FOB–LOCAL system (see

Figure 2). Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) tests applied to the level series for LOCAL, FOB, SHFE, and FX fail to reject the unit-root null hypothesis, with

p-values ranging from 0.2814 to 0.6916, confirming that all series are non-stationary in levels.

In first differences, the ADF statistics decisively reject the unit-root null for every variable (p = 0.0010), indicating stationarity after differencing. All variables are therefore integrated of order one, I(1), satisfying the conditions required for cointegration analysis. This integration structure motivates the use of the Engle–Granger error-correction framework to characterize long-run equilibrium and short-run dynamics along the SHFE–FOB–LOCAL chain.

Residual-based ADF tests from the Engle–Granger long-run regression also reject the unit-root null (h = 1, p = 0.0010), providing additional evidence of a stable cointegrating relationship among LOCAL, FOB, SHFE, and FX prices.

4.2. Long-Run Relationship: Engle–Granger Cointegration

The long-run domestic price equation is estimated using the Engle–Granger procedure:

Among the three long-run regressors, two exhibit positive and statistically significant coefficients(see

Table 3). FOB exerts the strongest direct long-run influence on domestic prices (

), while the exchange rate plays a smaller but significant role (

). By contrast, the SHFE coefficient is small and statistically insignificant (

), indicating no direct long-run effect once FOB and FX are controlled for.

Cointegration is strongly supported by the ADF test on the residuals (h = 1, p = 0.0010), confirming the presence of a stable long-run equilibrium. The estimated residuals form the error-correction term (ECT), which is used in subsequent dynamic specifications.

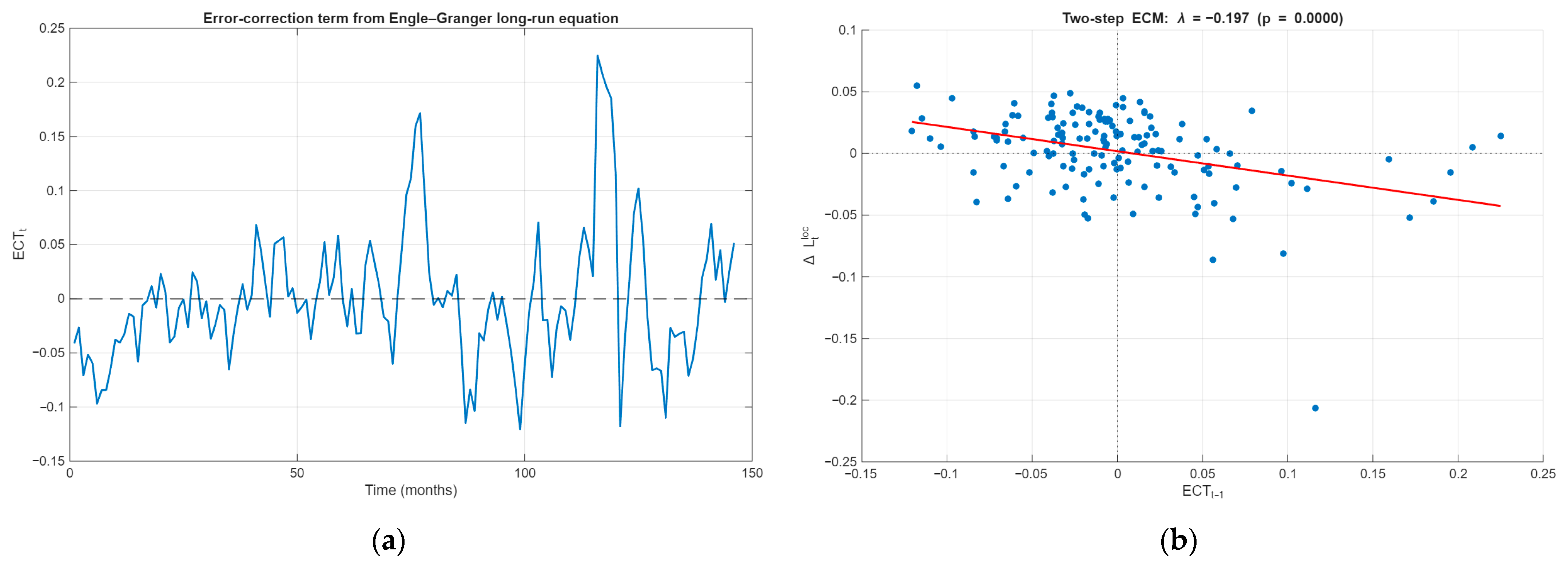

4.3. Speed of Adjustment: Two-Step ECM

To quantify the long-run adjustment mechanism, the Engle–Granger two-step ECM is estimated:

The estimated speed-of-adjustment coefficient is negative and statistically significant (

), implying that approximately 13% of deviations from the long-run equilibrium are corrected each week (see

Figure 3,

Table 4). This corresponds to a half-life of roughly five weeks, indicating gradual but systematic convergence toward long-run parity.

Because the two-step ECM isolates the lagged disequilibrium term from contemporaneous short-run shocks, the estimate of is not affected by multicollinearity, providing a reliable measure of long-run reversion.

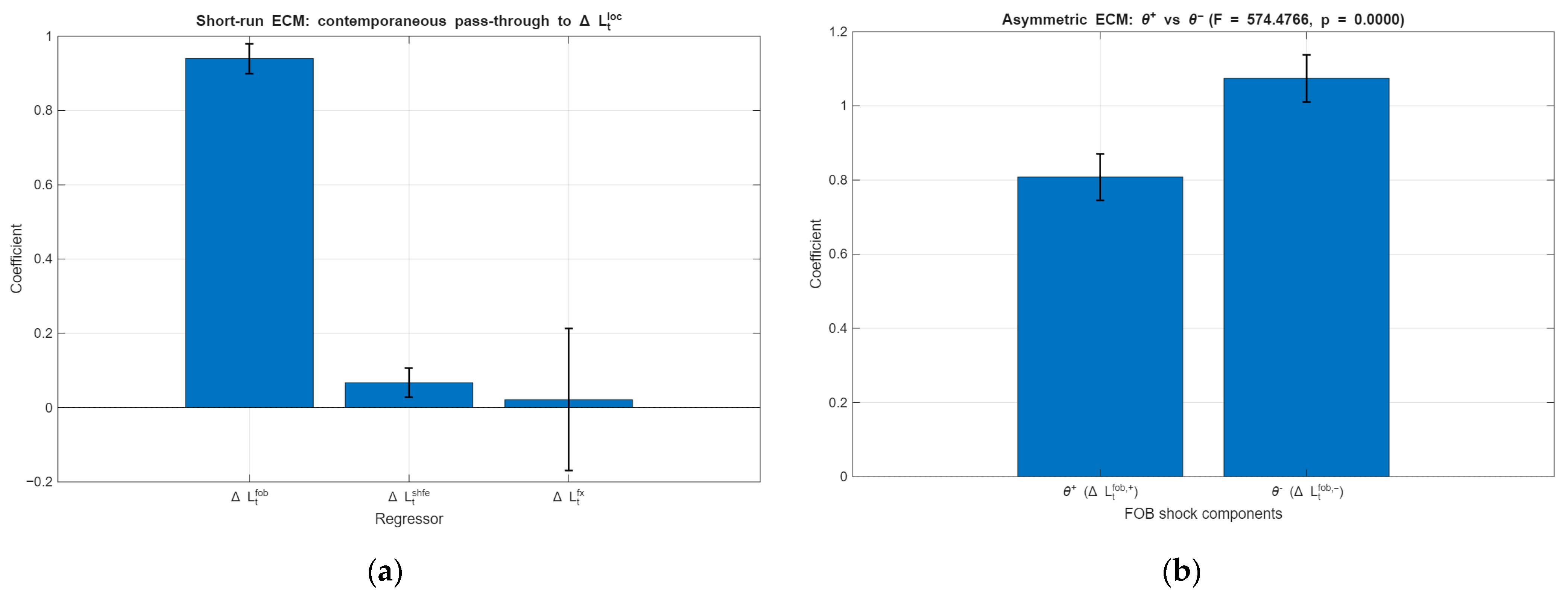

4.4. Short-Run and Asymmetric Transmission

4.4.1. Symmetric Short-Run ECM

Short-run pass-through is estimated using contemporaneous differenced regressors:

The estimated short-run elasticities indicate strong and immediate transmission from FOB to domestic prices (ΔFOB ≈ 0.94; see

Table 5). SHFE shocks exert a modest but statistically significant effect, while FX movements have no significant short-run impact. Overall, short-run adjustment operates primarily through the export channel.

The model exhibits high explanatory power (R2 = 0.836), confirming that weekly domestic price movements are closely linked to contemporaneous export-price changes.

4.4.2. Asymmetric ECM

To test for differential responses to positive and negative export shocks, and FOB price changes, are decomposed into positive and negative components:

The asymmetric ECM is specified as:

The results reveal pronounced asymmetry. Positive FOB shocks transmit strongly to domestic prices (

), whereas negative shocks have a much weaker effect (

). The null hypothesis of symmetry is decisively rejected (F = 574.48,

p < 0.001), indicating strongly upward-biased short-run pass-through (see

Table 6). These short-run and asymmetric transmission patterns are summarized in

Figure 4.

4.5. Machine-Learning Extension: ECM-Constrained Gradient Boosting

To assess potential nonlinearities beyond the linear ECM structure, an ECM-constrained gradient boosting model is estimated using the feature set:

The model preserves the validated long-run equilibrium while allowing for flexible short-run interactions. Out-of-sample evaluation (20% test sample) shows that the linear ECM slightly outperforms the ML variant (RMSE = 0.0188 vs. 0.0262; see

Table 7).

Feature-importance measures indicate that ΔFOB overwhelmingly dominates predictive performance, followed by ECT, ΔSHFE, and ΔFX (see

Figure 5). The ML extension does not uncover economically meaningful nonlinearities once the long-run structure is imposed, suggesting that short-run dynamics are predominantly linear.

Additional robustness checks, including subsample ECM estimates, alternative lag specifications, and residual-based and Johansen cointegration tests, are reported in

Appendix A Table A1,

Table A2,

Table A3 and

Table A4.

5. Discussion

The results provide a coherent account of how international price signals propagate through Thailand’s rubber price chain. The Engle–Granger estimates confirm a stable long-run cointegrating relationship among LOCAL, FOB, SHFE, and FX, with FOB serving as the dominant long-run anchor and FX contributing through the export-parity mechanism. The weak and statistically insignificant long-run coefficient on SHFE reflects its indirect role as an information benchmark rather than a price-setting variable. Futures-market signals are fully internalized at the FOB export level, where international benchmarks are converted into contract-relevant prices expressed in domestic currency, before reaching local markets. This hierarchical structure implies that SHFE influences domestic prices only indirectly, through its impact on export quotations rather than via a separate long-run transmission channel. The residual-based ADF test reinforces the presence of a well-defined equilibrium, consistent with established evidence on vertically linked commodity markets.

The two-step ECM reveals a moderate but highly stable speed of adjustment. The estimated coefficient (λ ≈ −0.134) implies that approximately 13% of disequilibrium is corrected each week, corresponding to a half-life of about five weeks. This adjustment speed is consistent with the frictions typical of perennial crop supply chains, including inventory smoothing, contracting practices, and quality differentiation. Rather than responding instantaneously to international shocks, domestic prices converge toward long-run parity through gradual, contract-mediated adjustment, supporting the view that global price alignment in Thailand’s rubber market operates primarily over the medium run.

Short-run dynamics display a distinctly different pattern. The symmetric ECM shows that domestic weekly price movements respond strongly and immediately to changes in FOB Bangkok quotations, with an elasticity close to unity (≈0.94). ΔSHFE exerts a smaller but statistically detectable effect, while ΔFX is largely irrelevant at the weekly frequency. These findings reinforce the interpretation of FOB Bangkok as the operative price-setting node, through which global information is transmitted to domestic markets, while futures prices and exchange rates play secondary or indirect roles in short-run adjustment.

The asymmetric ECM uncovers a pronounced and economically meaningful asymmetry. Positive FOB shocks generate very strong domestic responses (θ+ ≈ 1.074), whereas negative shocks produce only limited adjustment (θ− ≈ 0.067), and the symmetry restriction is decisively rejected. This upward-biased pass-through reflects underlying market-structure features rather than mechanical price rigidity. In particular, exporter dominance, grading and procurement rules, and contracting arrangements allow upward export-price movements to be transmitted rapidly, while downward adjustments are partially absorbed or delayed. Domestic prices therefore rise sharply during export upswings but decline only weakly during downturns. Such asymmetry reallocates price risk along the supply chain without implying price manipulation, highlighting the role of institutional and bargaining structures in shaping short-run price dynamics.

The machine-learning extension corroborates the econometric findings. The linear ECM outperforms the ECM-constrained gradient boosting model in out-of-sample forecasting, and feature-importance metrics show that ΔFOB overwhelmingly dominates short-run variation, followed by the lagged error-correction term. This result does not simply indicate that “linear models perform better,” but rather reflects the institutional nature of the market. Weekly price adjustments are governed by contracts, procurement cycles, and pricing rules, leaving limited scope for regime switching or complex nonlinear behavior at this frequency. Once the long-run equilibrium structure is correctly imposed, equilibrium correction dominates short-run noise, reducing the marginal gains from more flexible, opaque machine-learning specifications. The ECM-constrained GBM therefore serves as a diagnostic validation tool rather than a substitute for the structural model.

Overall, the findings converge on three core insights. First, Thailand’s domestic rubber prices are tightly anchored to international benchmarks in the long run through an export-parity mechanism centered on FOB pricing. Second, short-run adjustments are governed almost entirely by export quotations, confirming the hierarchical nature of price transmission. Third, domestic prices respond asymmetrically to international shocks, with positive export shocks transmitting far more strongly than negative ones due to market structure and contracting features. These patterns underscore the importance of policy instruments that enhance transparency in export-price formation, strengthen liquidity and risk-sharing mechanisms during downturns, and improve the capacity of smallholders and processors to manage price risk along the supply chain.

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

This study investigates the dynamic transmission of international rubber price signals along the SHFE–FOB–LOCAL chain using an integrated framework that combines Engle–Granger cointegration, two-step error-correction modeling, symmetric and asymmetric short-run specifications, and an ECM-constrained machine-learning extension. The empirical evidence demonstrates a coherent and economically interpretable structure in which Thailand’s domestic rubber prices are tightly linked to export-parity benchmarks in the long run while adjusting sharply and asymmetrically to short-run export-price shocks.

The Engle–Granger and residual-based ADF tests confirm a stable long-run equilibrium binding LOCAL, FOB, SHFE, and FX prices. Within this relationship, FOB emerges as the dominant long-run anchor with an elasticity slightly above unity, while FX contributes positively through the export-parity mechanism. Once FOB and FX are controlled for, SHFE does not exert a direct long-run effect, indicating that futures prices function primarily as upstream information signals that are fully internalized at the export-pricing stage rather than as independent price-setting forces in domestic markets.

Adjustment toward the long-run equilibrium is moderate and consistent. The two-step ECM yields an adjustment coefficient of approximately −0.134, implying that around 13% of disequilibrium is corrected each week. This convergence speed reflects the frictions inherent in physical trading, procurement cycles, and quality differentiation within Thailand’s rubber supply chain.

Short-run dynamics differ markedly from the long-run structure. The symmetric short-run ECM shows strong and nearly instantaneous pass-through from ΔFOB (≈0.94), a modest influence of ΔSHFE, and no meaningful effect from ΔFX. The asymmetric specification reveals a striking and statistically decisive asymmetry: positive export-price shocks transmit strongly (θ+ ≈ 1.074), while negative shocks transmit only weakly (θ− ≈ 0.067). This upward-biased adjustment pattern is consistent with market-structure features such as exporter dominance, grading and procurement rules, and delayed downward price adjustment, which collectively shape how international shocks are distributed along the supply chain.

The machine-learning extension corroborates the econometric conclusions. The ECM-constrained gradient boosting model does not outperform the linear ECM in out-of-sample forecasting, and predictor-importance metrics show that ΔFOB overwhelmingly governs short-run movements. These results suggest that Thailand’s rubber price system is governed primarily by contractual arrangements and equilibrium-correction mechanisms, with limited evidence of regime switching or nonlinear dynamics at the weekly frequency once the long-run structure is imposed. The machine-learning extension therefore plays a confirmatory role, reinforcing rather than displacing the error-correction framework as the core tool for understanding price transmission in this market.

Taken together, the findings yield several policy implications with direct relevance for market participants and policymakers. First, given the dominance of FOB-driven adjustment, exporters and processors can improve price-risk management by anchoring hedging strategies to FOB export benchmarks rather than relying on direct exposure to futures markets such as SHFE, which function primarily as upstream information signals. Second, the pronounced asymmetry in short-run transmission has clear implications for smallholder farmers: because negative export-price shocks are weakly passed through, income volatility during downturns is best addressed through income-smoothing instruments—such as formula-based support schemes or countercyclical transfers—rather than attempts to suppress short-term price movements. Third, for policymakers, the results indicate that stabilization policies are more effective when they operate through transparent, rule-based mechanisms aligned with export-parity pricing—such as benchmark-linked buffer stocks or automatic adjustment rules—rather than discretionary interventions that target weekly price fluctuations. More durable outcomes may therefore arise from strengthening long-run market integration through improved transparency in FOB price formation, wider access to exchange-rate and export-linked hedging instruments, and institutional arrangements that reduce producer exposure to unfavorable global shocks.

Future research could extend this work by incorporating higher-frequency SHFE data, time-varying parameter models, or analyses of synthetic rubber and downstream tire markets to capture broader vertical linkages and evolving market structures in the regional rubber economy.