1. Introduction

Innovation is the core driver of high-quality economic development in China, and corporate R&D investment is a critical pillar of technological innovation. From 2010 to 2022, R&D spending of Chinese listed firms has grown steadily, yet the country still faces bottlenecks in core technology innovation. Corporate R&D decisions are shaped by both internal factors (firm performance, governance) and external factors (industry competition, policy support). Among these, peer effects, where firms mimic or respond to the R&D behaviors of peer enterprises, have received insufficient attention in the context of Chinese institutional settings.

Existing studies on peer effects in R&D investment suffer from three key limitations: (1) Static and single-dimensional peer definition: Most studies define peers by industry or region alone (

Matray, 2021;

Sevilir, 2017), ignoring dynamic firm characteristics such as ownership and scale. (2) Limited analysis of dynamic persistence: Few studies explore how peer effects reinforce the persistence of R&D investment over time (

Cohen & Sinha, 2013). (3) Insufficient context-specific analysis: Research on peer effects in Chinese firms lacks integration with the country’s unique institutional and market features (

Firth et al., 2015).

This study addresses these gaps by: (1) Proposing a four-dimensional dynamic matching method (year-industry-ownership-scale quantile) to accurately identify peer firms (

Faulkender & Yang, 2010). (2) Examining the dynamic persistence of R&D investment and the amplifying role of peer effects (

Moon & Weidner, 2017). (3) Providing empirical evidence from Chinese A-share listed firms to enrich the cross-country literature on peer effects in innovation (

Basse Mama, 2017;

Matray, 2021).

This study aims to: (1) verify the existence of positive peer effects in Chinese firms’ R&D investment; (2) uncover the underlying mechanisms (social learning, knowledge spillover, institutional legitimacy); (3) offer practical implications for firms and policymakers. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews relevant literature and develops research hypotheses, while also presenting the theoretical and conceptual frameworks.

Section 3 details the methodology, including data sources, variable definitions and measurements, model specifications, and diagnostic tests.

Section 4 reports and discusses empirical results, including descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, mediation analysis, robustness tests, and endogeneity treatment.

Section 5 discusses the theoretical and practical implications, as well as study limitations.

Section 6 concludes the study.

2. Literature Review, Hypothesis Development, and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Literature Review

Innovation is an essential driver of economic progress, with firms playing a central role in this process (

Romer, 1990;

Aghion et al., 2019). Understanding the factors that influence a firm’s innovation behavior is critical for both theoretical research and practical applications. Scholars have long examined how different elements, such as social learning and knowledge flow, contribute to shaping innovation within firms (

Rogers, 2010;

Cohen & Sinha, 2013). These factors interact in complex ways, creating dynamic environments where firms innovate internally and draw from external sources of knowledge and inspiration. This section explores these crucial drivers of innovation, including how mutual learning and knowledge flows influence firms’ innovation behaviors and the broader development of innovation ecosystems.

2.1.1. Social Learning and Imitation in Firm Innovation Behavior

Researchers have established that reciprocal learning and imitation across companies significantly influence innovation behavior, resulting in the emergence of peer effects (

Bandura, 1977;

Sevilir, 2017). According to social learning theory, firms in close geographical proximity or within the same industry group tend to observe and learn from each other’s innovation activities.

Matray (

2021) conducted a study of U.S.-listed companies and found that innovation efforts from adjacent companies could stimulate similar R&D decisions. This phenomenon of innovation spillover becomes weaker as the geographical distance between firms increases. Two primary drivers of this spillover effect are the movement of R&D personnel and the influx of external venture capital, which fosters innovation within regional clusters (

Audretsch & Feldman, 1996). Thus, both internal operations and external factors, particularly from adjacent companies, influence a firm’s innovative conduct (

Lazear & Rosen, 1981).

2.1.2. The Role of Knowledge Flow in Innovation and R&D Investment

The flow of knowledge is essential for innovation, as it enables the exchange of ideas and mitigates uncertainty and expenses related to R&D efforts (

Stam & Wennberg, 2009). Scholars, such as

Peri (

2005), have shown through patent citation analysis that knowledge diffusion through mutual learning among organizations is far more extensive than traditional trade flows, highlighting its positive impact on both firm and national innovation. However, knowledge flow tends to be confined within firms that share similar technological capabilities, as core competitive technologies in these firms are related. Effective knowledge transfer often relies on informal channels rather than formal communication methods, as firms generally treat R&D knowledge as proprietary (

Belenzon & Schankerman, 2013;

Jaffe et al., 2000).

R&D investment is a primary driver of firm innovation, and its impact is often shaped by peer effects. While there is limited direct evidence of peer effects in R&D investment, research has shown that the actions of firms influence each other’s investment decisions. For example,

Park and Lee (

2023) found that the interaction between firms had a substantial impact on their investment behavior, including their R&D investment choices. This peer effect on investment behavior has been observed in various industris, including the aviation sector (

Shin et al., 2016). Similarly,

Basse Mama (

2017) corroborated the existence of peer effects in R&D investments in European markets, further supporting the idea that innovation behaviors within regional clusters have a peer effect that drives R&D investment and innovation forward.

2.2. Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks

2.2.1. Theoretical Foundations

The exploration of peer effects in Chinese firms’ R&D investment relies on three interrelated theoretical pillars, which collectively explain why firms adjust innovation strategies based on peers and how such adjustments drive R&D investment decisions—aligning with the study’s focus on Chinese A-share listed firms (2010–2022) and Dynamic Matching-based peer matching logic.

(I) Social Learning Theory

Rooted in

Bandura’s (

1977) insights, Social Learning Theory holds that firms acquire R&D strategies through observing and imitating peers, rather than through sole trial-and-error. For Chinese firms, R&D investment is high-risk and uncertain (e.g., long cycles, ambiguous returns), especially amid China’s shift to high-quality growth (

Huang & Wang, 2023). Peers (via “year-industry-ownership-size quantile” dynamic matching) serve as “informational references”: firms lacking independent R&D experience can infer feasible investment levels from peers’ behaviors, reducing uncertainty (

Sevilir, 2017). As

Matray (

2021) confirmed for U.S. firms, geographic/industrial clustering amplifies this observation, making peer imitation a practical way to avoid falling behind competitively, directly justifying the positive correlation between peer and focal firms’ R&D investment.

(II) Knowledge Spillover Theory

Formalized by

Arrow (

1962) and expanded by

Jaffe et al. (

2000), Knowledge Spillover Theory argues that innovation-related knowledge (tacit or explicit) spills over between firms via labor mobility, industry collaboration, or patent disclosure. This reduces the marginal cost of R&D for recipient firms. In China, industry clusters (fostered by innovation policies) and shared talent pools make spillovers particularly prominent among Dynamic-matched peers. For example, a peer’s R&D in new energy battery tech may spill over to focal firms via engineer mobility, enabling focal firms to invest in complementary R&D at lower cost.

Peri (

2005) and

Belenzon and Schankerman (

2013) further validate that such spillovers are most effective among technologically similar firms—supporting the study’s peer-matching criteria and explaining why peer R&D boosts focal firms’ investment willingness.

(III) Institutional Theory

Based on

DiMaggio and Powell (

1983), Institutional Theory emphasizes that firms conform to peer behaviors to gain legitimacy amid institutional pressures (e.g., government policies, industry norms). In China, the government’s positioning of innovation as a “core growth driver” (19th National Congress) creates normative/coercive pressure for R&D (

Firth et al., 2015). Peers identified through the “year-industry-ownership nature-size quantile” dynamic matching—those sharing homogeneous operating periods, industrial contexts, ownership attributes, and scale levels—serve as precise “legitimacy benchmarks”. For state-owned enterprises (SOEs) within the same dynamic matching group, mimicking peer SOEs’ R&D behaviors helps them align with state innovation expectations and policy requirements; for non-SOEs in the same matched group, aligning R&D investment with peers enables them to meet industry normative standards, thereby accessing government innovation subsidies and enhancing market trust (

Kowalski et al., 2013). This mechanism explains why firms with R&D investment below the average level of their dynamically matched peers proactively increase R&D input: legitimacy concerns drive them to align with the R&D norms of homogeneous peers, ultimately reinforcing the positive peer effect in corporate R&D investment.

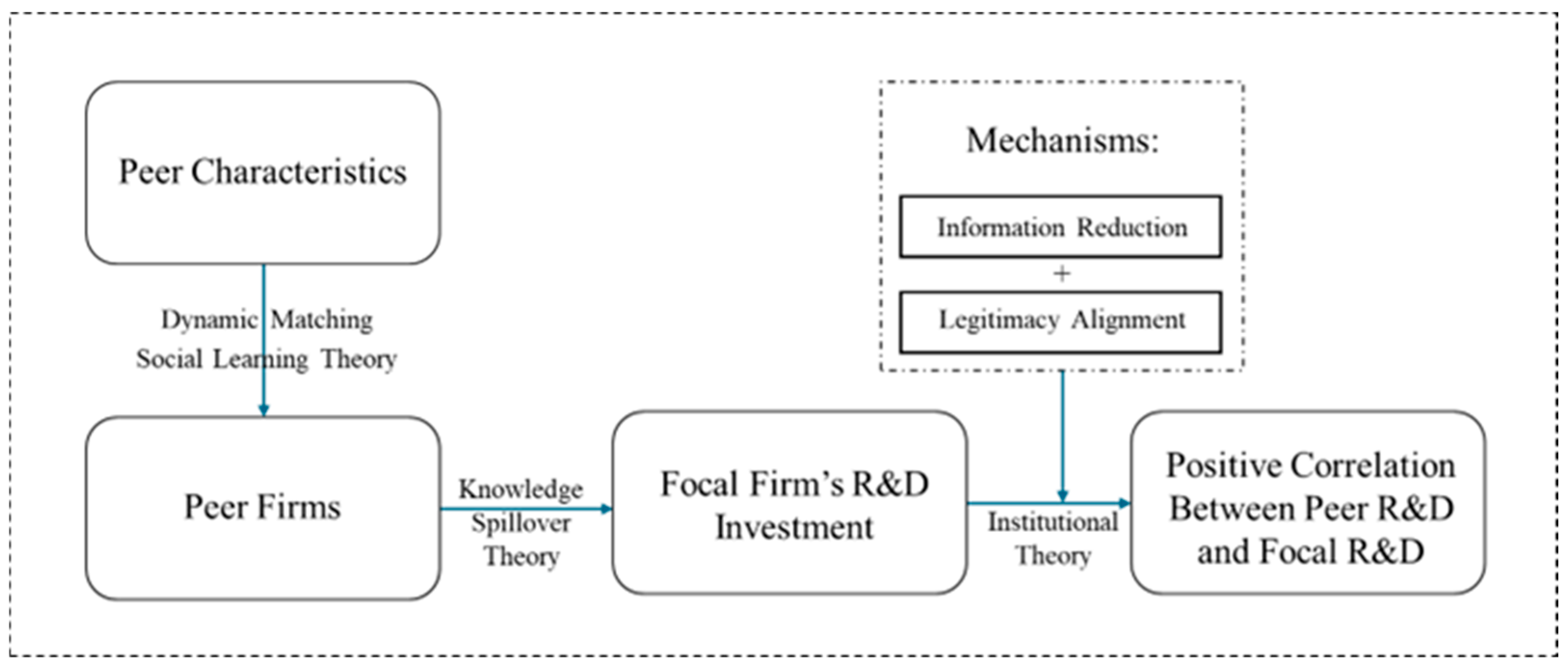

2.2.2. Conceptual Framework

The conceptual framework (

Figure 1) illustrates the influence of peer firms on the R&D investment of focal firms. First, the characteristics of peer firms, such as industry, scale, and property rights, determine the specific group of peer firms through dynamic matching based on the Dynamic Matching Social Learning Theory. Second, these peer firms directly affect the R&D investment of focal firms through the knowledge spillover theory. Meanwhile, based on institutional theory, the dual mechanisms of “information reduction (reducing information asymmetry)” and “legitimacy alignment (aligning with industry legitimacy expectations)” further act on the R&D investment of focal firms.

2.3. Hypothesis Development

H1. There exists a significant positive peer effect in the R&D investment of Chinese firms, meaning the R&D investment level of peer firms exhibits a significant positive correlation with the R&D investment decisions of focal firms.

R&D investment of Chinese firms is characterized by high risks, long cycles, and uncertain returns. Particularly during the stage of economic transformation toward high-quality development, firms face relatively high information costs and decision-making risks when formulating independent R&D strategies. From the perspective of social learning, the R&D behaviors of peer firms (matched by industry, scale, and ownership nature) can provide reliable informational references for focal firms, helping them reduce uncertainty in judging technological trends and market demands, and further imitate a reasonable level of R&D input. From the lens of Knowledge Spillover Theory, R&D activities of peer firms generate knowledge externalities through channels such as talent mobility and technological exchanges. Focal firms can absorb this spilled knowledge to lower their own marginal costs of R&D, thereby enhancing the feasibility of R&D investment. Grounded in Institutional Theory, the government’s innovation policy orientation and industry competition norms create institutional pressure. By aligning their behaviors with the R&D activities of peer firms, focal firms can obtain legitimate resources such as policy support and market trust, which strengthens the rationality of their R&D investment.

In summary, the R&D investment of peer firms exerts a positive impact on the R&D decisions of focal firms through three pathways: information transmission, cost reduction, and legitimacy enhancement. Hence, the hypothesis is proposed.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Source

The sample consists of Chinese A-share non-financial listed firms from 2010 to 2022, sourced from the CSMAR database. We exclude: (1) financial firms; (2) ST/PT firms; (3) firms with missing R&D or financial data. The final sample includes 12,876 firm-year observations, with data winsorized at the 1% level to mitigate outliers.

3.2. Description of Variables

To improve clarity and transparency,

Table 1 presents the detailed definitions, measurements, units, and data sources of all key variables, including dependent variables, independent variables, and control variables.

3.3. Peer Identification: Four-Dimensional Dynamic Matching

To precisely define the peer firms of focal firms, this paper adopts a dynamic matching method based on the cross-classification of four core dimensions. The peer scope is dynamically updated according to the annual changes in firms’ four core dimensions: year, industry, ownership type, and size quantile (size_rank). This dynamic matching method, through multi-dimensional precise grouping and annual update mechanisms, not only guarantees the homogeneity of peer firms (similar industry, ownership, and size) but also avoids the timeliness bias of static matching, providing a reliable sample foundation for the subsequent identification of peer R&D effects. The specific matching logic is as follows:

Industry Dimension: It is based on the industry code of enterprises to ensure that peer enterprises are in the same industrial environment. They face consistent technological iteration rhythms, market competition patterns and policy supervision requirements, which conform to the basic premise of “intra-industry interaction” in the peer effect.

Ownership Nature Dimension: It distinguishes between state-owned enterprises (state = 1) and non-state-owned enterprises (state = 0). Due to the significant differences in resource acquisition capacity, decision-making mechanisms and R&D motivation among enterprises with different ownership natures, separate grouping can avoid the interference of ownership heterogeneity on the identification of peer effect.

Size Dimension: Enterprise size is taken as the core matching feature. After grouping by year—industry—ownership nature, enterprises in each group are divided into 10 quantiles according to size (size_rank = 1–10). This ensures that peer enterprises are highly similar in asset scale and operating volume.

Dynamic Update Dimension: The size quantiles are recalculated, and peer membership is redefined every year. This captures the dynamic changes of enterprise size over time (such as expansion and contraction) and avoids the “lag distortion of peer relationships” caused by static matching.

3.4. Empirical Models

3.4.1. Basic Dynamic Panel Model

To test the peer effect, we construct the dynamic panel model:

where

RDi,t denotes the R&D investment intensity of focal firm

i in year

t;

peerit represents the average R&D investment intensity of peer firms of focal firm

i in year

t;

RDi,t−1 denotes the one-period lagged R&D investment intensity of focal firm

i, serving to capture the path dependence inherent in R&D decision-making.

Controli,t denotes a set of control variables (return on assets, operating growth, firm age, industry dummy, year dummy);

μi is the firm-fixed effect;

λt is the year-fixed effect;

εi,t is the random error term.

3.4.2. Model Selection Justification

We use the Hausman test to determine whether to adopt the fixed-effects model (FE) or the random-effects model (RE). The Hausman test examines whether there is a correlation between individual effects and explanatory variables. If the null hypothesis (no correlation) is rejected, the fixed-effects model is more appropriate; otherwise, the random-effects model is selected (

Greene, 2018). Additionally, considering the dynamic nature of the model (inclusion of lagged dependent variable), the system GMM method is further used to address potential endogeneity issues (

Blundell & Bond, 1998). We do not adopt the ordinary least squares (OLS) model because it cannot control for firm-fixed effects and may lead to biased estimates (

Montgomery et al., 2021).

3.5. Diagnostic Tests

To ensure the reliability of the empirical results, the following diagnostic tests are conducted:

3.5.1. Panel Unit Root Test

Panel unit root tests are crucial for assessing the stationarity of variables, as non-stationary data may result in spurious regressions (

Greene, 2018). This study employs two classic panel unit root tests: the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test and the Phillips-Perron (PP) test. The null hypothesis is “the variable has a unit root (non-stationary)”. If the

p-value of the test statistic is less than 0.05, we reject the null hypothesis, indicating the variable is stationary.

3.5.2. Multicollinearity Test (VIF)

The variance inflation factor (VIF) is used to test multicollinearity.

Montgomery et al. (

2021) note that a VIF > 5 indicates severe multicollinearity. This study calculates VIF for all independent variables, with the average VIF used to judge overall collinearity. VIF is a more formal and comprehensive measure than Pearson correlation analysis, as it inherently incorporates correlation information (VIF = 1/(1 − R

2)).

3.5.3. Heteroskedasticity and Cross-Sectional Dependence Test

Heteroskedasticity: The Breusch-Pagan/Cook-Weisberg test is used (

Greene, 2018). The null hypothesis is “no heteroskedasticity”; if the

p-value < 0.05, heteroskedasticity exists, and robust standard errors are used in regressions.

Cross-Sectional Dependence: The Lagrange Multiplier (LM) test is used. The null hypothesis is “no cross-sectional dependence”; if the

p-value < 0.05, cross-sectional dependence exists, and Driscoll–Kraay standard errors are adopted (

Driscoll & Kraay, 1998), which is robust to cross-sectional dependence, autocorrelation, and heteroskedasticity.

3.5.4. Autocorrelation Test

The Wooldridge test (

Wooldridge, 2010) is used to detect autocorrelation in the panel model. The null hypothesis is “no first-order autocorrelation in the idiosyncratic errors”. If the

p-value < 0.05, first-order autocorrelation is present. For models with autocorrelation, we incorporate lagged terms of variables or use Driscoll–Kraay standard errors to address it.

3.6. Endogeneity Treatment

Endogeneity issues (omitted variables, reverse causality, measurement errors) may exist in the model. We have adopted two methods to address this:

3.6.1. Dynamic Panel System GMM Model

In hypothesis testing, the key focus is on the coefficient β2; if β2 is statistically significant and positive, the hypothesis that peer effects exist in R&D investment among Chinese listed companies is supported.

3.6.2. Instrumental Variables (IV)

We use two instrumental variables that satisfy relevance and exogeneity conditions:

IV1 (Average Registration Type of Peer Firms): A firm’s registration type is an institutional choice made at the time of establishment, which is exogenous to current R&D decisions (

Rajan & Zingales, 2003). Firms with similar registration types have similar governance structures and innovation incentives, so it is correlated with peer R&D intensity.

IV2 (Lagged One-Period Peer R&D Intensity): The lagged term of peer R&D intensity is a historical variable, which is not affected by current focal firm’s R&D decisions, avoiding reverse causality (

Acemoglu & Autor, 2011). Due to R&D inertia, lagged peer R&D intensity is correlated with current peer R&D intensity.

3.7. Robustness Tests

To ensure the stability of the findings, we conduct four robustness tests:

Addressing omitted variable bias: Introduce market competition index (HHI) and industry firm density (Ln(N)) as additional control variables.

Replacing the explained variable: Use RD1 (R&D expenses/total assets) instead of the benchmark RD.

Shortening the sample period: Exclude data from 2020 to 2022 to avoid the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Alternative peer definition: Divide firm size into 5 quantiles instead of 10 to redefine peers.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistical results of the core variables. The dependent variable RD has a mean of 0.053 and a median of 0.041, indicating that the overall R&D investment level of sample firms is moderate with a certain degree of distribution skewness; its standard deviation is 0.045, with a minimum value of 0.001 and a maximum value of 0.293, suggesting significant differences in R&D investment intensity among different firms.

The core explanatory variable peer has a mean of 0.055 (slightly higher than that of RD) and a median of 0.052, indicating that the overall R&D investment level of peer firms is slightly higher than the average level of sample firms, which provides a data foundation for examining the impact of peer effect on firms’ own R&D.

For control variables, firm profitability (roa) has a mean of 0.040, a median of 0.038, reflecting certain fluctuations in the profitability of sample firms; firm growth (growth) has a mean of 0.301, a median of 0.142, indicating significant differences in growth capacity; firm age (age) has a mean of 9.835, a median of 8, showing a wide age range of sample firms.

In general, the sample size and value range of each variable are consistent with research expectations, with no obvious outliers or data missing issues, laying a reliable data foundation for subsequent empirical analysis.

4.2. Diagnostic Test Results

4.2.1. Panel Unit Root Test Result

Table 3 presents the results of the panel unit root tests for core variables. For RD and peer, both ADF and PP tests reject the null hypothesis of a unit root (

p < 0.0001), indicating that all core variables are stationary series (I(0)). Thus, there is no spurious regression problem, and panel regression analysis can be conducted directly.

4.2.2. VIF Test

Table 4 presents the VIF test results. The average VIF of all independent variables is 1.06, and the VIF value of each variable is less than 2, which is far below the critical value of 5 (

Montgomery et al., 2021). This indicates that there is no severe multicollinearity problem in the model, and the regression results are reliable.

4.2.3. Heteroskedasticity, Autocorrelation, and Cross-Sectional Dependence Test

Heteroskedasticity: The Breusch-Pagan/Cook-Weisberg test yields Chi

2 = 188.00, Prob > chi

2 = 0.0000 < 0.05, indicating the presence of heteroskedasticity. We use robust standard errors in all regressions to correct for it (

Greene, 2018).

Autocorrelation: The Wooldridge test for first-order autocorrelation yields F = 19.50, Prob > F = 0.0000 < 0.05, rejecting the null hypothesis of no first-order autocorrelation. We adopt Driscoll–Kraay standard errors to address this issue (

Driscoll & Kraay, 1998).

Cross-Sectional Dependence: The LM test yields Chi2 = 234.56, Prob > chi2 = 0.0000 < 0.05, indicating the presence of cross-sectional dependence. Driscoll–Kraay standard errors are used to handle this problem.

4.3. Dynamic Matching Validity

4.3.1. Size Matching Accuracy

We use the intra-group size coefficient of variation (size_cv = intra-group size standard deviation/intra-group size mean) to test the accuracy of size matching. The results (

Table 5) show that the annual mean value of size_cv from 2010 to 2022 ranges between 0.0055 and 0.0068, with an overall mean of only 0.0064, which is much lower than the critical standard of 0.3. This indicates minimal differences in enterprise size within peer groups and highly accurate size matching.

4.3.2. Matching Dynamics

The annual change ratio of enterprise size quantiles (size_rank) is calculated to verify the dynamic update effect. The results show that during 2010–2022, 25.3% of enterprises adjusted their size quantile groups due to scale changes. This ratio is within a reasonable range, reflecting the normal characteristics of enterprise development and confirming that dynamic matching can accurately capture changes in enterprise size.

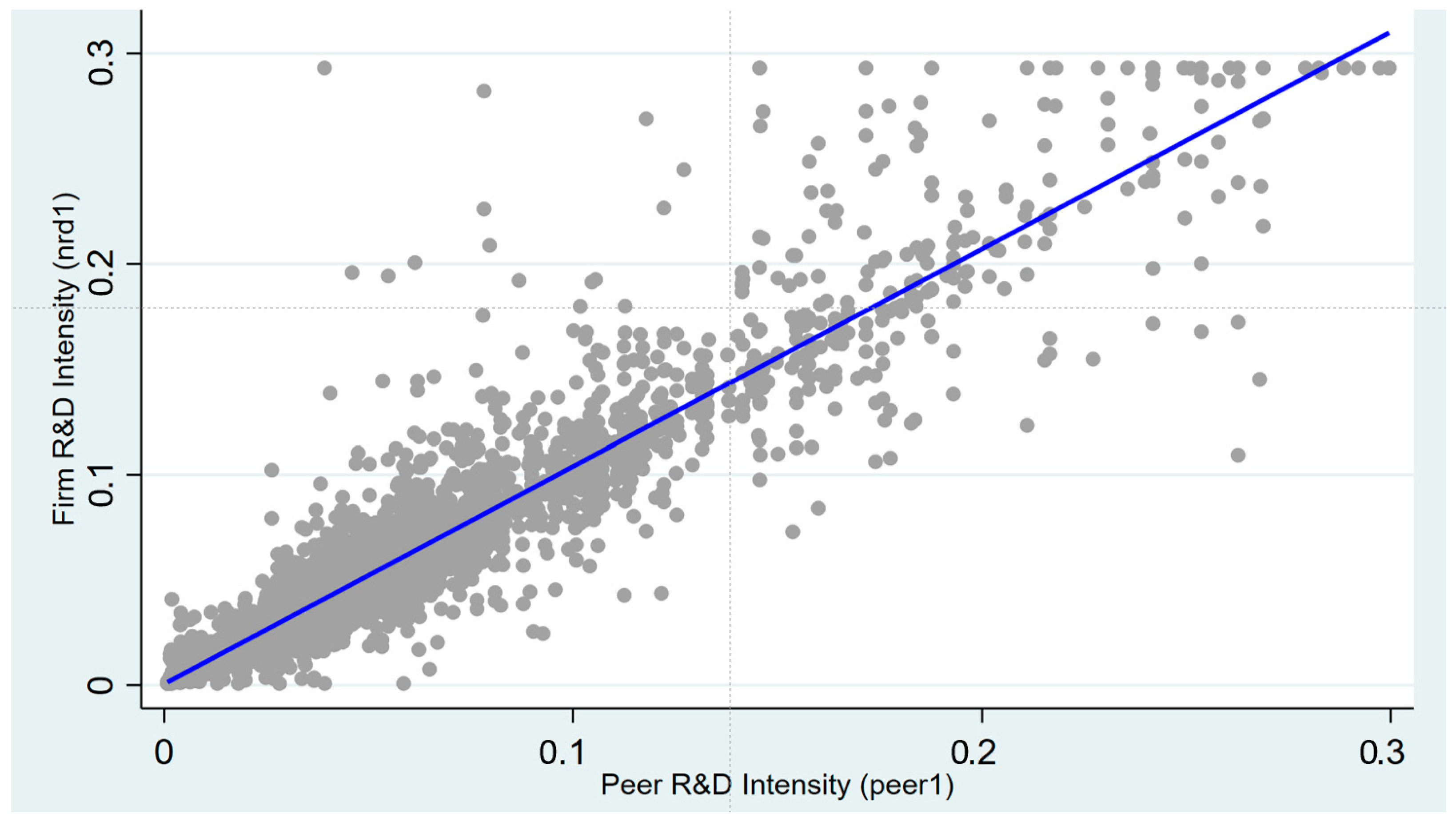

4.3.3. Visual Validation of Core Variables Correlation

Figure 2 presents the correlation scatter plot and fitting results of RD and peer. The blue fitting line shows a clear upward trend, indicating a significant positive correlation between a firm’s own R&D intensity and peer firms’ R&D intensity. This provides intuitive visual evidence for the existence of the peer effect.

4.4. Regression Results

4.4.1. Model Selection (Hausman Test)

We use the Hausman test to determine the applicability of the fixed-effects model (FE) and the random-effects model (RE). The test results show that Chi2 (1) = 143.80 and Prob > chi2 = 0.0000. Since the p-value is much less than 0.05, we reject the null hypothesis that “there is no systematic difference between the coefficients of FE and RE”, indicating a correlation between individual effects and explanatory variables. Therefore, the fixed-effects model (FE) should be selected for subsequent analysis.

4.4.2. Basic Dynamic Regression Result Analysis

Table 6 presents the basic dynamic regression results. In both columns (1) and (2), the coefficient of peer is significantly positive (0.587 *** and 0.023 **, respectively), indicating that peer R&D intensity has a robust positive impact on focal firms’ R&D investment, which initially supports Hypothesis H1.

The lagged term of R&D investment (L.RD) also shows a significantly positive coefficient, indicating that R&D investment exhibits strong dynamic persistence. After incorporating industry and year fixed effects (column 2), the coefficient of peer remains significant, confirming the stability of the peer effect.

For control variables, the coefficient of roa is significantly negative (−0.087 ***), implying that firms with strong profitability may prefer short-term profit-making projects rather than long-term R&D investment. The coefficients of growth and age are not statistically significant, indicating that firm growth and age have no significant impact on R&D investment in this sample.

4.5. Endogeneity Inspection

4.5.1. Dynamic Panel System GMM Model Result Analysis

Table 7 reports the results of the system GMM model. The coefficient of peer is significantly positive (0.104 *** and 0.087 **), further verifying the existence of a positive peer effect. The lagged term L.RD is also significantly positive, confirming the dynamic persistence of R&D investment.

The Wald chi-square test results (7.36 and 37.86, p < 0.05) indicate that the model is statistically significant. By controlling lagged terms and using the Dynamic Panel System GMM method, endogeneity issues are effectively alleviated, and the results are more reliable.

4.5.2. Instrumental Variables (IV) Result Analysis

Table 8 presents the IV regression results. The coefficients of peer are significantly positive (0.123 *** for IV1 and 0.184 *** for IV2), confirming the causal relationship between peer R&D intensity and focal firm R&D investment.

The first-stage regression results show that the F-statistics of IV1 and IV2 are 1184.9 and 1616.66, respectively, which are much higher than the critical value of 16.38 (5% significance level), indicating that there is no weak instrumental variable problem. This further supports the validity of the conclusions.

4.6. Robustness Test

To verify the scientific validity and robustness of the conclusions, this study employs two robustness tests to assess the reliability of the results. They are addressing the omitted variable bias and replacing the explained variable and core explanatory variable.

4.6.1. Addressing the Omitted Variable Bias

Table 9 presents the results of robustness tests by introducing HHI and Ln(N). The coefficient of peer remains significantly positive (0.056 ** to 0.058 **), indicating that the positive peer effect is robust after controlling for market competition and industry density.

4.6.2. Replacing the Explained Variable and Shortening the Sample Period

Table 10 presents the results of robustness tests by replacing the dependent variable (RD1) and shortening the sample period (2010–2019). The coefficient of peer remains significantly positive in all columns, confirming that the peer effect is not affected by variable measurement or sample period selection.

4.6.3. Alternative Peer Definition

We redefine peers by dividing firm size into 5 quantiles instead of 10. The regression results (

Table 11) show that the coefficient of peer is still significantly positive (0.062 **), confirming the robustness of the peer effect.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

First, this study enriches the research framework of peer effects in corporate R&D investment. Existing literature has confirmed the existence of peer effects in corporate decisions (

Faulkender & Yang, 2010), but there is a lack of in-depth exploration of the formation mechanism and identification methods of peer effects in R&D investment in the context of China’s economic transformation. This study constructs a four-dimensional dynamic matching framework of “year—industry—ownership nature—size quantile” to accurately identify peer enterprises, which solves the problem of ambiguous peer definition in previous studies (

Matray, 2021;

Sevilir, 2017) and provides a new methodological reference for the accurate identification of peer effects in R&D investment.

Second, this study expands the application scenarios of three classical theories in the field of corporate innovation. By integrating Social Learning Theory, Knowledge Spillover Theory and Institutional Theory, this study reveals the multi-path transmission logic of peer effects on corporate R&D investment: from the perspective of Social Learning Theory, peer firms (identified by dynamic matching) provide reliable informational references for focal firms, helping reduce R&D decision uncertainty (

Bandura, 1977); based on Knowledge Spillover Theory, the R&D activities of homogeneous peers generate knowledge externalities (e.g., through talent mobility or technical exchanges), lowering the marginal cost of R&D for focal firms (

Jaffe et al., 2000); grounded in Institutional Theory, aligning R&D behaviors with peers helps focal firms gain institutional legitimacy such as policy support or market trust (

DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). The consistent positive and significant coefficient of peer effects in baseline regressions, system GMM estimates, and instrumental variable regressions (

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8) further corroborates that these theoretical pathways jointly drive focal firms’ R&D investment. This not only provides empirical support for the cross-integration application of multiple theories but also deepens the academic understanding of the internal logic of peer effects affecting corporate innovation behavior.

Third, this study supplements the research on the dynamic characteristics of corporate R&D investment. The results show that R&D investment has significant dynamic persistence, and peer effects can further strengthen this persistence. This finding enriches the research on the dynamic adjustment mechanism of corporate R&D investment (

Moon & Weidner, 2017) and helps to explain the formation process of R&D investment differences among enterprises from a dynamic perspective.

Compared with recent studies, this study has distinct contributions. For example,

Matray (

2021) focused on the local innovation spillover effect of U.S.-listed firms, while this study focuses on the Chinese context, supplementing cross-country evidence.

Basse Mama (

2017) confirmed the peer effect in European markets, but did not explore the transmission logic in depth. This study fills these gaps by combining precise peer identification, theoretical mechanism deduction, and context-specific research.

5.2. Practical Implications

For enterprises, they should rationally utilize peer effects to optimize R&D investment decisions. On the one hand, enterprises should establish an effective peer learning mechanism, actively track and learn from the R&D strategies and experience of peer enterprises in the same industry, with similar scale and the same ownership nature, to reduce the uncertainty and information cost of independent R&D decision-making. For example, small and medium-sized non-state-owned enterprises can refer to the R&D investment ratio of peer enterprises to avoid blind investment or under-investment. On the other hand, enterprises should pay attention to the knowledge spillover effect brought by peer R&D activities, strengthen technical exchanges and talent cooperation with peer enterprises, and absorb external knowledge and technology to reduce their own R&D costs. For instance, enterprises can participate in industry innovation alliances to promote knowledge sharing with peers.

For the government, it is necessary to give full play to the guiding role of policies and promote the positive spillover of peer effects in R&D investment. The government can further optimize the innovation policy environment, encourage the formation of industrial clusters (e.g., high-tech industrial parks), and create conditions for technical exchange and knowledge sharing among enterprises. For state-owned enterprises and non-state-owned enterprises, different policy guidance can be adopted. For example, state-owned enterprises can be encouraged to take the lead in carrying out R&D innovation in key core technologies to play a demonstration role, while non-state-owned enterprises can be supported through subsidies and tax incentives to enhance their ability to follow up R&D. In addition, the government should strengthen the construction of information disclosure system, improve the transparency of corporate R&D information (e.g., disclose R&D investment intensity, R&D projects, and patent achievements), and help enterprises better identify peer reference objects.

For the industry, it is necessary to establish a sound industry self-regulation mechanism and promote sound competition and cooperation among enterprises. Industry associations can play a bridge role, organize R&D exchange activities (e.g., technical seminars, peer visits), build a platform for technical cooperation among enterprises, and promote the positive interaction of R&D investment among peer enterprises. At the same time, it is necessary to standardize the competition order of the industry, avoid vicious competition such as homogenized R&D caused by blind imitation, and guide enterprises to carry out differentiated innovations based on learning from peers. For example, industry associations can formulate technical standards and guide enterprises to focus on different technical directions.

5.3. Study Limitations

This study still has some limitations that need to be improved in future research. First, in the selection of peer enterprise matching dimensions, this study only considers four core dimensions: year, industry, ownership nature and size quantile. In fact, factors such as corporate governance structure (e.g., board size, equity concentration) and technological distance (e.g., patent similarity) may also affect the definition of peer enterprises (

Belenzon & Schankerman, 2013). Future research can further expand the matching dimensions to improve the accuracy of peer identification.

Second, this study focuses on the overall impact of peer effects on corporate R&D investment, but does not explore the heterogeneous impact of peer effects under different scenarios. For example, the intensity of peer effects may vary in different industries (high-tech vs. low-tech), enterprise life cycles (start-up vs. mature), and regional innovation environments (eastern vs. western China) (

Czarnitzki & Thorwarth, 2020). Future research can conduct group regression analysis for different scenarios to deeply explore the boundary conditions of peer effects.

Third, this study mainly uses quantitative research methods to verify the existence of peer effects and their correlation with theoretical mechanisms. Although a variety of robustness tests and endogeneity processing methods are adopted to ensure the reliability of the results, the depth of analysis on the micro-behavior of enterprises is insufficient. Future research can combine qualitative research methods such as case studies and interviews to further reveal the specific process of peer effects affecting corporate R&D investment. For example, select representative enterprises in a specific industry to conduct in-depth interviews and analyze how they learn from peers and adjust R&D strategies.

Fourth, this study does not consider the potential negative effects of peer effects. For example, excessive imitation may lead to homogenized competition and inhibit independent innovation (

Lazear & Rosen, 1981). Future research can explore the double-edged sword effect of peer effects and provide more comprehensive implications for corporate R&D decision-making.

6. Conclusions

This study takes Chinese A-share non-financial listed companies from 2010 to 2022 as the research sample, and empirically investigates the existence, mechanism and impact of peer effects in corporate R&D investment through dynamic matching, panel data analysis and instrumental variable methods. The main conclusions are as follows:

First, there is a significant positive peer effect in the R&D investment of Chinese enterprises. The R&D investment level of peer enterprises has a significant positive impact on the R&D investment decisions of focal enterprises. After a series of robustness tests such as replacing variables, shortening the sample period, addressing omitted variable bias, and alternative peer definition, this conclusion still holds.

Second, the peer effect in R&D investment is transmitted through three mechanisms: social learning, knowledge spillover and institutional legitimacy. Focal enterprises reduce R&D decision-making uncertainty by learning from peer R&D behaviors, reduce R&D costs through absorbing peer knowledge spillovers, and obtain policy support and market trust by aligning with peer R&D behaviors to meet institutional legitimacy requirements.

Third, R&D investment has significant dynamic persistence, and the lagged term of R&D investment has a significant positive impact on current R&D investment. Meanwhile, the peer effect can further strengthen this persistence, promoting enterprises to maintain a stable R&D investment level.

Fourth, in the control variables, the return on assets has a significant negative impact on R&D investment, indicating that enterprises with strong profitability may prefer short-term profit-making projects rather than long-term R&D investment. However, the impact of enterprise growth and age on R&D investment is not significant.

This study not only enriches theoretical research on peer effects and corporate R&D investment, but also provides practical enlightenment for enterprises to optimize R&D investment decisions, the government to formulate innovation policies and the industry to promote sound development. In the future, enterprises should rationally use peer effects to improve R&D efficiency, the government should create a good policy environment to promote the positive spillover of peer effects, and the industry should strengthen the cooperation and exchange mechanism to realize the win-win situation of R&D innovation among enterprises.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.T.; methodology, H.T.; software, H.T.; validation, S.P. and D.T.N.; formal analysis, H.T.; writing—original draft preparation, H.T.; writing—review and editing, S.P. and D.T.N.; visualization, S.P.; supervision, D.T.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. No new datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study. For further inquiries regarding data availability, please contact the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RD | R&D investment |

| peer | Peer effect |

| IV | Instrumental Variable |

| GMM | Generalized Method of Moments |

References

- Acemoglu, D., & Autor, D. (2011). Skills, tasks and technologies: Implications for employment and earnings. In Handbook of labor economics (Vol. 4, pp. 1043–1171). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Aghion, P., Bergeaud, A., Blundell, R. W., & Griffith, R. (2019). The innovation premium to soft skills in low-skilled occupations. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3489777 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Arrow, K. J. (1962). Economic welfare and the allocation of resources for invention. In Readings in industrial economics: Volume two: Private enterprise and state intervention (pp. 219–236). Macmillan Education UK. [Google Scholar]

- Audretsch, D. B., & Feldman, M. P. (1996). R&D spillovers and the geography of innovation and production. The American Economic Review, 86(3), 630–640. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basse Mama, H. (2017). The interaction between stock prices and corporate investment: Is Europe different? Review of Managerial Science, 11(2), 315–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belenzon, S., & Schankerman, M. (2013). Spreading the word: Geography, policy, and knowledge spillovers. Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(3), 884–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M. L., & Sinha, E. (2013). National patterns of R&D resources: Future directions for content and methods: Summary of a workshop. National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Czarnitzki, D., & Thorwarth, S. (2020). Productivity effects of basic research in low-tech and high-tech industries. Research Policy, 41(9), 1555–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, J. C., & Kraay, A. C. (1998). Consistent covariance matrix estimation with spatially dependent panel data. Review of Economics and Statistics, 80(4), 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkender, M., & Yang, J. (2010). Inside the black box: The role and composition of compensation peer groups. Journal of Financial Economics, 96(2), 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, M., Leung, T. Y., Rui, O. M., & Na, C. (2015). Relative pay and its effects on firm efficiency in a transitional economy. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 110, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, W. H. (2018). Econometric analysis (8th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z., & Wang, Q. (2023). R&D investment, media attention and executive pay-performance sensitivity. Co-Operative Economy & Science, 43(5), 116–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, A. B., Trajtenberg, M., & Fogarty, M. S. (2000). Knowledge spillovers and patent citations: Evidence from a survey of inventors. American Economic Review, 90(2), 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, P., Büge, M., Sztajerowska, M., & Egeland, M. (2013). State-owned enterprises: Trade effects and policy implications. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Lazear, E. P., & Rosen, S. (1981). Rank-order tournaments as optimum labor contracts. Journal of Political Economy, 89(5), 841–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matray, A. (2021). The local innovation spillovers of listed firms. Journal of Financial Economics, 141(2), 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D. C., Peck, E. A., & Vining, G. G. (2021). Introduction to linear regression analysis. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, H. R., & Weidner, M. (2017). Dynamic linear panel regression models with interactive fixed effects. Econometric Theory, 33(1), 158–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B., & Lee, C. Y. (2023). Does R&D cooperation with competitors cause firms to invest in R&D more intensively? evidence from Korean manufacturing firms. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 48(3), 1045–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Peri, G. (2005). Determinants of knowledge flows and their effect on innovation. Review of Economics and Statistics, 87(2), 308–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, R. G., & Zingales, L. (2003). The great reversals: The politics of financial development in the twentieth century. Journal of Financial Economics, 69(1), 5–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. M. (2010). Diffusion of innovations. Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Romer, P. M. (1990). Capital, labor, and productivity. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. Microeconomics, 1990, 337–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilir, M. (2017). Learning across peer firms and innovation waves: Working paper. Indiana University-Bloomington. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, K., Kim, S. J., & Park, G. (2016). How does the partner type in R&D alliances impact technological innovation performance? A study on the Korean biotechnology industry. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 33(1), 141–164. [Google Scholar]

- Stam, E., & Wennberg, K. (2009). The roles of R&D in new firm growth. Small Business Economics, 33(1), 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |