Healthcare Financing Vulnerability and Service Utilization in Kenya During the COVID-19 Pandemic, with a Focus on Policies to Protect Human Capital

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Research Problem

2. Related Literature

3. Data, Methodology, and Analytical Frameworks

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Theoretical Model

3.3. Empirical Model

3.4. Study Limitations

4. Results

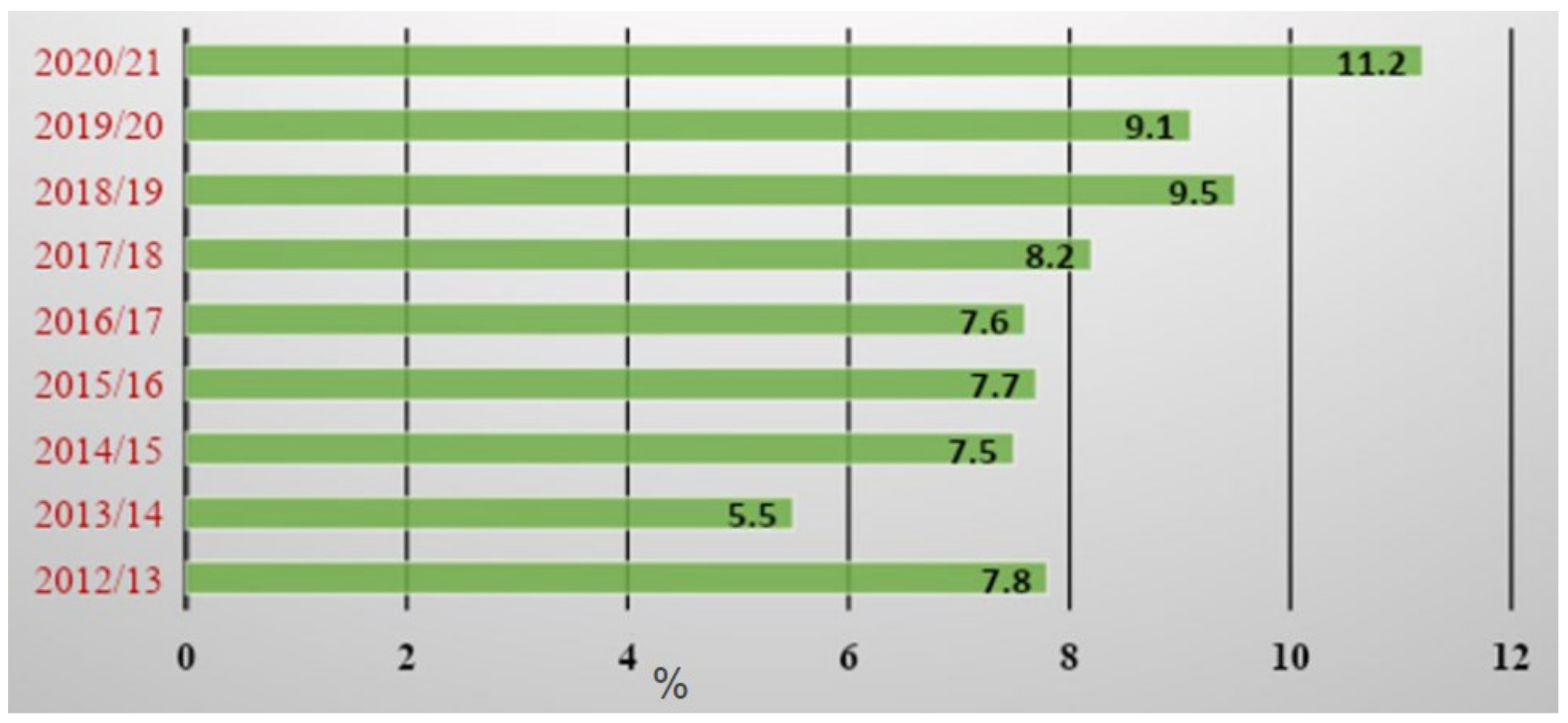

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

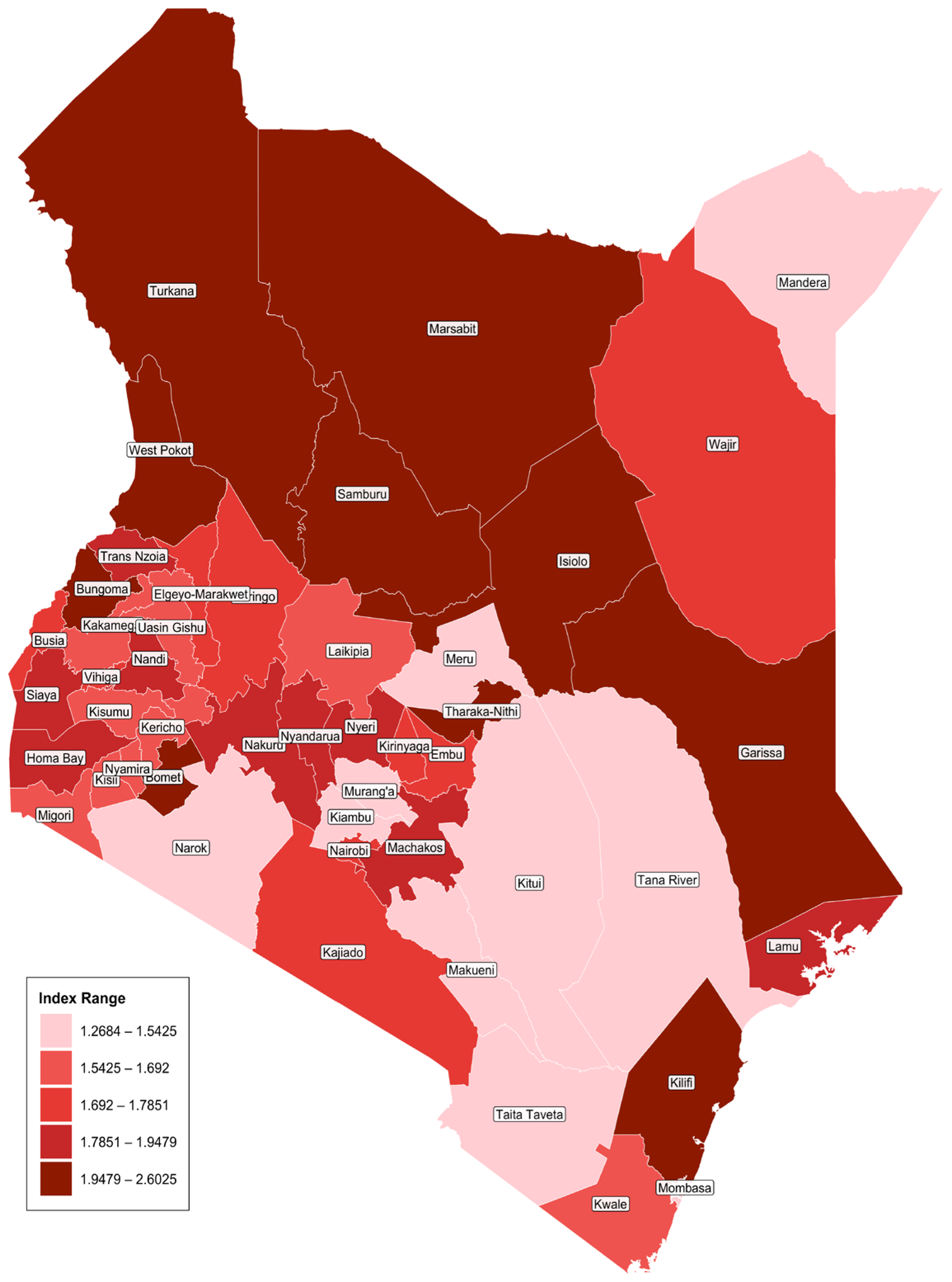

4.2. Spatial Distribution of Health Financing Vulnerability Index

4.3. Drivers of the Utilization of Healthcare Services

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adelekan, T., Mihretu, B., Mapanga, W., Nqeketo, S., Chauke, L., Dwane, Z., & Baldwin-Ragaven, L. (2020). Early effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on family planning utilisation and termination of pregnancy services in Gauteng, South Africa: March–April 2020. Wits Journal of Clinical Medicine, 2(2), 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, A. E., Coulborn, R. M., Perez, V., & Larson, E. L. (2008). Effect of hand hygiene on infectious disease risk in the community setting: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 98(8), 1372–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apicella, M., Campopiano, M. C., Mantuano, M., Mazoni, L., Coppelli, A., & DelPrato, S. (2020). COVID-19 in people with diabetes: Understanding the reasons for worse outcomes. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, 8(9), 782–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barasa, E., Kazungu, J., Orangi, S., Kabia, E., Ogero, M., & Kasera, K. (2021). Indirect health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic in Kenya: A mixed methods assessment. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barden-O’Fallon, J., Barry, M. A., Brodish, P., & Hazerjian, J. (2015). Rapid Assessment of Ebola-Related Implications for Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Service Delivery and Utilization in Guinea. PLoS Currents Outbreaks, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G. S. (1965). A theory of the allocation of time. Economic Journal, 75(299), 493–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolkan, H. A., van Duinen, A., Samai, M., Bash-Taqi, D. A., Gassama, I., Waalewijn, B., Wibe, A., & von Schreeb, J. (2018). Admissions and surgery as indicators of hospital functions in Sierra Leone during the west-African Ebola outbreak. BMC Health Services Research, 18, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brolin Ribacke, K. J., van Duinen, A. J., Nordenstedt, H., Höijer, J., Molnes, R., Froseth, T. W., Koroma, A. P., Darj, E., Bolkan, H. A., & Ekström, A. (2016). The impact of the West Africa Ebola outbreak on obstetric health care in Sierra Leone. PLoS ONE, 11, e0150080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, C., Gearing, M. E., DeMatteis, J., Levin, K., Mulcahy, T., Newsome, J., & Wivagg, J. (2022). Financial vulnerability and the impact of COVID-19 on American households. PLoS ONE, 17(1), e0262301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, J. F., Ouma, J., Lubyayi, L., Amone, A., Aol, L., Sekikubo, M., Musoke, P., & Le Doare, K. (2021). Indirect effects of COVID-19 on maternal, neonatal, child, sexual and reproductive health services in Kampala, Uganda. BMJ Global Health, 6(8), e006102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuma, J., Musimbi, J., Okungu, V., Goodman, C., & Molyneux, C. (2009). Reducing user fees for primary health care in Kenya: Policy on paper or policy in practice? International Journal for Equity in Health, 8(1), 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuma, J., & Okungu, V. (2011). Viewing the Kenyan health system through an equity lens: Implications for universal coverage. International Journal for Equity in Health, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damiano, K., Oleche, M., Muriithi, M., Mutegi, R., Wambugu, A., & Mwabu, G. (2021). The impact of COVID19 incidence, COVID-19 vulnerability and Business closure due to COVID-19 on wages in Kenya. ACEIR working paper. ACEIR. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X., & Tian, X. (2015). Multiple component analysis and its application in process monitoring with prior fault data. IFAC-Papers Online, 48(21), 1383–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorward, J., Khubone, T., Gate, K., Ngobese, H., Sookrajh, Y., Mkhize, S., Jeewa, A., Bottomley, C., Lewis, L., Baisley, K., & Butler, C. C. (2021). The impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on HIV care in 65 South African primary care clinics: An interrupted time series analysis. The Lancet HIV, 8(3), e158–e165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edeh, H. C., Nnamani, A. U., & Ozor, J. O. (2025). Effect of COVID-19 on catastrophic medical spending and forgone care in Nigeria. Economies, 13(5), 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elston, J. W. T., Moosa, A. J., Moses, F., Walker, G., Dotta, N., Waldman, R. J., & Wright, J. (2016). Impact of the Ebola outbreak on health systems and population health in Sierra Leone. Journal of Public Health, 38(4), 673–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epo, B. N., Baye, F. M., Mwabu, G., Manda, D. K., Ajakaiye, O., & Kipruto, S. (2025). Human capital, household prosperity, and social inequalities in Sub-Saharan Africa. Economies, 13(8), 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, M. (1972). On the concept of health capital and demand for health. The Journal of Political Economy, 80(2), 223–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hategeka, C., Carter, S. E., Chenge, F. M., Katanga, E. N., Lurton, G., Mayaka, S. M. N., & Grépin, K. A. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and response on the utilisation of health services in public facilities during the first wave in Kinshasa, the Democratic Republic of the Congo. BMJ Global Health, 6(7), e005955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houeninvo, H., Quenum, V. C. C., & Senou, M. M. (2023). Out-Of-Pocket health expenditure and household consumption patterns in Benin: Is there a crowding out effect? Health Economics Review, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hren, R. (2012). Theoretical shortcomings of the Grossman model. Bulletin: Economics, Organisation and Informatics in Health Care, 28(1), 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Janssens, W., Pradhan, M., De Groot, R., Sidze, E., Donfouet, H. P. P., & Abajobir, A. (2021). The short-term economic effects of COVID-19 on low-income households in rural Kenya: An analysis using weekly financial household data. World Development, 138, 105280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H., Yang, J., Kim, E., & Lee, J. (2021). The effect of mid-to-long-term hospitalization on the catastrophic health expenditure: Focusing on the mediating effect of earned income loss. Healthcare, 9, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y., Wabyona, E., Udahemuka, F. R., Traore, A., & Doocy, S. (2023). Economic impact of COVID-19 on income and use of livelihoods-related coping mechanisms in Chad. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 7, 1150242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansiime, M. K., Tambo, J. A., Mugambi, I., Bundi, M., Kara, A., & Owuor, C. (2020). COVID-19 implications on household income and food security in Kenya and Uganda: Findings from a rapid assessment. World Development, 137, 105199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. (2020). Inequality trends and diagnostics in Kenya. A joint report on multidimensional inequality in Kenya. Ministry Planning and Development, Report KNBS Publication, Republic of Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- Kitole, F. A., Lihawa, R. M., Nsindagi, T. E., & Tibamanya, F. Y. (2023). Does health insurance solve health care utilization puzzle in Tanzania? Public Health, 219, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leftie, P. (2013). Uhuru’s madaraka gifts, saturday nation. Google Scholar WorldCat. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, M., Gao, L., Cheng, C., Zhou, Q., Uy, J. P., Heiner, K., & Sun, C. (2020). Efficacy of face mask in preventing respiratory virus transmission: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease, 36, 101751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macharia, P. M., Joseph, N. K., & Okiro, E. A. (2020). A vulnerability index for COVID-19: Spatial analysis at the subnational level in Kenya. BMJ Global Health, 5(8), e003014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ministry of Health. (2021). Kenya national health accounts 2016/17–2018/19. Government of Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, National Coordinating Agency for Population and Development & ORC Macro. (2005). Kenya service provision assessment survey 2004. Kenya National l Bureau of Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Medical Services & Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation. (2009a). Kenya household health expenditure and utilisation survey report 2007. Ministry of Health, Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Medical Services & Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation. (2009b). Kenya national health accounts 2005–2006. Ministry of Health, Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- Muriithi, K. M., & Mwabu, G. (2014). Demand for health care in Kenya: The effects of information about quality. In P. V. Scaafer, & E. Kouassi (Eds.), Econometric methods for analyzing economic development (pp. 102–109). IGI (Global). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwabu, G. (2009). The production of child health in Kenya: A structural model of birth weight. Journal of African Economies, 18(2), 212–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwabu, G., Mwanzia, J., & Liambila, W. (1995). User charges in government health facilities in Kenya: Effect on attendance and revenue. Health Policy Planning, 10, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2018). Health-care utilization as a proxy in disability determination. The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2013, March 25–26). Health care financing and the sustainability of health systems. 2nd Meeting of the joint Network on Fiscal Sustainability of Health Systems, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Ogwang, T., & Mwabu, G. (2025). A simple measure of catastrophic health expenditures. Health Economics. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onditi, F., Obimbo, M. M., Kinyanjui, S. M., & Nyadera, I. N. (2020). Rejection of Containment Policy in the Management of COVID-19 in Kenyan Slums: Is Social Geometry an Option? Research Square. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partnership for Evidence-Based Response to COVID-19. (2020). Using data to find a balance. Special report series: Disruption to essential health services in Africa during COVID-19. Available online: https://preventepidemics.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/PERCBrief (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Puro, N., & Kelly, R. J. (2021). Community social vulnerability index and hospital financial performance. Journal of Health Care Finance, 48(12), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Kenya. (2012–2023). Government budgetary allocations. National Treasury. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, T., Sully, E., Ahmed, Z., & Biddlecom, A. (2020). Estimates of the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on sexual and reproductive health in low-and middle-income countries. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 46, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenzweig, M. R., & Schultz, T. P. (1983). Estimating a Household Production Function: Heterogeneity, the Demand for Health Inputs, and their Effects on Birth Weight. Journal of Political Economy, 91(5), 723–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifa, M., & Leibbrandt, M. (2017). Urban poverty and inequality in Kenya. Urban Forum, 28, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimeles, T., Asrat Kassu, R., Bogale, G., Bekele, M., Getnet, M., Getachew, A., & Abraha, M. (2021). Magnitude and associated factors of poor medication adherence among diabetic and hypertensive patients visiting public health facilities in Ethiopia during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE, 16(4), e0249222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siedner, M. J., Kraemer, J. D., Meyer, M. J., Harling, G., Mngomezulu, T., Gabela, P., & Herbst, K. (2020). Access to primary health care during lockdown measures for COVID-19 in rural South Africa: A longitudinal cohort study. Available online: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.05.15.20103226v1 (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Solymári, D., Kairu, E., Czirják, R., & Tarrósy, I. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on the livelihoods of Kenyan slum dwellers and the need for an integrated policy approach. PLoS ONE, 17(8), e0271196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacey, O., Kairu, A., Malla, L., Ondera, J., Mbuthia, B., Ravishankar, N., & Ba-rasa, E. (2021). Impact of free maternity policies in Kenya: An interrupted time-series analysis. BMJ Global Health, 6, e003649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, J. (1986). Does better nutrition raise farm productivity? Journal of Political Economy, 94(2), 297–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K. (2015). Cases and issues in Japanese private international law. Japanese Yearbook of International Law, 58, 384–396. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, R. K. (2021). Health services demand and utilization. In Health services planning. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamai, R. (2009). Health care policy administration and reforms in post-colonial Kenya and challenges for the future. In T. Veintie, & P. Virtanen (Eds.), Local and global encounters: Norms, identities and representations in formation. The Renvall Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Wambua, S., Malla, L., Mbevi, G., Kandiah, J., Nwosu, A. P., Tuti, T., Paton, C., Wambu, B., English, M., & Okiro, E. A. (2022). Quantifying the indirect impact of COVID-19 pandemic on utilisation of outpatient and immunisation services in Kenya: A longitudinal study using interrupted time series analysis. BMJ Open, 12(3), e055815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittenberg, M., & Leibbrandt, M. (2017). Measuring Inequality by asset indices: A general approach with application to south Africa. Review of Income and Wealth, 63(4), 706–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D., Wong, R., & Hakizimana, D. (2021). Rapid assessment on the utilization of maternal and child health services during COVID-19 in Rwanda. Public Health Action, 11(1), 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2002). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2015). Control function methods in applied econometrics. Journal of Human Resources, 50(2), 420–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2020). World bank COVID-19 response: Operations policy and country services. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/factsheet/2020/10/14/world-bank-covid-19-response (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Zar, H. J., Dawa, J., Bueno, G., & Castro-Rodriguez, J. A. (2020). Challenges of COVID-19 in children in low-and middle-income countries. Paediatric Respiratory Reviews, 35, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Description | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Employment | A dummy variable taking the value 1 for not being employed, and a value of zero otherwise. | Persons who are not employed are more vulnerable to the inability to afford health care finance than those who are employed (Bruce et al., 2022; Kitole et al., 2023). |

| Employment type | A dummy variable taking the value 1 for part-time employment, zero for full employment. | Those in part-time employment are more vulnerable to lack of funds to pay for health care compared to those in full-time employment (Kitole et al., 2023) |

| Health insurance | A dummy variable taking the value 1 for not having insurance, zero otherwise; | Persons without health insurance are more vulnerable to inability to pay for health care, a situation that increases HFVI (Kitole et al., 2023) |

| Employer’s medical benefits | A dummy variable taking the value 1 for not having the employer’s medical benefits, 0 otherwise; | The households without medical benefits are more vulnerable to inability to use care (Kitole et al., 2023) |

| Cash payments | A dummy variable taking the value 1 for not paying for health services in cash, and 0 otherwise. | Persons paying in cash are less vulnerable to inability to finance health care (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018; Houeninvo et al., 2023) |

| Variables | Measurement |

|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | |

| Utilization of health care services | A dummy variable taking the value 1 if any member of the household visited any health facility in the past 7 days, 0 otherwise |

| Explanatory Variables | |

| Health Financing Vulnerability Index (HFv) | This is a continuous variable constructed from dummy variables in Table 1 using Uncentered PCA |

| The Z vector in Equation (3) contains: The natural logarithm of the cost of medical services, including medical and non-medical costs | A continuous variable indicating the natural logarithm of the total amount in Kshs paid for the item(s)/service(s) used in service delivery |

| The natural logarithm of the cost of other related commodities, such as food | A continuous variable indicating the natural logarithm of the total amount in Kshs paid for food items |

| Marital Status of an individual | A dummy variable that takes the value 1 if one is married, 0 otherwise |

| Residence | A dummy variable taking the value 1 if an individual resides in an urban area, 0 otherwise |

| Gender | A dummy variable taking the value 1 if an individual is male, 0 otherwise |

| The natural logarithm of the age | The natural logarithm of the age of an individual in years |

| Primary Education Level | A dummy variable taking the value 1 if an individual has primary education, 0 otherwise |

| Secondary Education Level | A dummy variable taking the value 1 if an individual has secondary education, 0 otherwise |

| University Education Level | A dummy variable taking the value 1 if an individual has a university education, 0 otherwise |

| The natural logarithm of the household size | A continuous variable indicating the natural logarithm of the total number of household members |

| Pre-existing health conditions | A dummy variable taking the value 1 if there is a pre-existing health condition, such as diabetes, etc., 0 otherwise |

| Instrumental Variable (IV) | This is a non-self-county mean of HFVI constructed by getting the county mean for all HFVIs, except for the index of individual i, so that the mean is exogenous to individual i. |

| Predicted residual of HFVI, i.e., | This is a continuous variable generated from a reduced-form regression of the potentially endogenous HFVI on all exogenous variables and the instrumental variable |

| Interaction of the predicted residual with HFVI, i.e., | This is a continuous variable generated by interacting the predicted residual of HFVI with the potentially endogenous HFVI |

| Variables | Mean | Standard Deviation | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare Services Utilization | 0.1616 | 0.3681 | 0 | 1 |

| Health Financing Vulnerability Index (HFVI) | 1.72 | 7.0955 | 0 | 5.1925 |

| Natural log of price of medical services in Kshs | 6.0376 | 1.2294 | 0 | 11.5129 |

| Natural log of the prices of food items in KSh | 6.9650 | 0.7855 | 2.3026 | 11.2252 |

| Married (=1) | 0.1160 | 0.3202 | 0 | 1 |

| Area of residence (rural area = 1) | 0.5218 | 0.4995 | 0 | 1 |

| Gender (man = 1) | 0.4795 | 0.4996 | 0 | 1 |

| Natural log of age of the respondent | 3.5217 | 0.3975 | 2.8904 | 4.7005 |

| Primary education level (=1) | 0.3008456 | 0.4586 | 0 | 1 |

| Secondary education level (=1) | 0.4357432 | 0.4958 | 0 | 1 |

| University education level (=1) | 0.0337578 | 0.1806 | 0 | 1 |

| Pre-existing health condition (=1) | 0.0010863 | 0.0329 | 0 | 1 |

| Natural logarithm of the Household size | 1.456351 | 0.5740 | 0 | 3.2958 |

| County level Mean of Health Financing Vulnerability Index (Instrumental Variable) | 1.4 | 0.0643 | 0 | 3.9 |

| Predicted residual of HFVI | −9.14 × 10−10 | 5.368562 | −4.65507 | 51.56799 |

| Interaction of the predicted residual with HFVI | 28.81862 | 211.0986 | −5.098032 | 2651.902 |

| Explanatory Variables | First Stage Regression: Reduced-Form Estimates Dependent Variable: Health Financing Vulnerability Index (HFVI) | Second Stage Regression: Control Function Estimates Dependent Variable: Healthcare Utilization (=1) |

|---|---|---|

| Health Financing Vulnerability Index | --- | −0.8088 (0.0474) |

| Log Total Cost of Medicines | −0.1849 *** (0.0445) | 0.2673 *** (0.0201) |

| Log Total Cost of Food items | 0.3071 *** (0.0629) | 0.4924 *** (0.0201) |

| Married (=1) | 0.8093 *** (0.1829) | 0.9239 *** (0.0581) |

| Area of Residence Rural area (=1) | 0.0659 (0.1074) | 0.0209 (0.02630) |

| Gender Male (=1) | 0.1399234 (0.1074) | 0.0669122 *** (0.0269) |

| Log Age of the Respondent | 0.6537 *** (0.1384) | 0.5632 *** (0.0449) |

| Primary (=1) | 0.22618 (0.1485) | 0.0078 (0.0375) |

| Secondary level (=1) | 0.1810 (0.1465) | 0.0071 (0.0362) |

| University level (=1) | 0.6864 ** (0.3241) | 0.4343 *** (0.0837) |

| Pre-existing Conditions (=1) | 2.175815 *** (1.0368) | 2.7923 *** (0.2920) |

| Log of Household Size | −0.7695 *** (0.1053) | −0.3541 *** (0.0450) |

| Non-self County Mean for HFVI (×10) | 4.081 *** (0.0368) | ----- |

| Predicted HFVI residual | ----- | 0.8076 *** (0.0470) |

| Interaction of predicted residual with HFVI | ----- | −0.0003 (0.0002) |

| Constant | −1.3141 * (0.7147) | −4.2716 *** (0.1971) |

| Diagnostic Statistics | F(12, 59838) = 14.27 (p-value: 0.000) R-sq. = 0.0167 Adj R-sq = 0.0155 Root MSE = 5.3736 | LR Chisq (14) = 1301.49 (p = 0.000) Prob > chi2 (p = 0.0000) Pseudo R2 = 0.0953 Log likelihood = −6176.41 |

| Variables | Probit Marginal Effects |

|---|---|

| Healthcare Financing Vulnerability Index (HFVI) | −0.3117 *** (0.0182) |

| Log of medical input costs | 0.1100 *** (0.0068) |

| Log the cost of food items | 0.1898 *** (0.0078) |

| Married (=1) | 0.3539 *** (0.0199) |

| Area of residence, Rural (=1) | 0.0080 (0.0101) |

| Gender, Male (=1) | 0.0258 *** (0.0104) |

| Log Age of the respondent | 0.2171 *** (0.0173) |

| Primary level (=1) | 0.0030 (0.0142) |

| Secondary level (=1) | 0.0027 (0.0135) |

| University level (=1) | 0.1716 *** (0.0329) |

| Pre-existing conditions (=1) | 0.6006 *** (8.46) |

| Log Household size | −0.1365 *** (0.0173) |

| HFVI_predicted residual | 0.3113 *** (0.0182) |

| Interaction of HFVI with predicted residual | −0.0001 (0.0001) |

| Variables | Probit Marginal Effects |

|---|---|

| Health Financing Vulnerability Index (HFVI) | −0.3117 *** (0.0182) |

| Log of medical input costs | 0.1100 *** (0.0068) |

| Log the cost of food items | 0.1898 *** (0.0078) |

| Married (=1) | 0.3539 *** (0.0199) |

| Area of residence, Rural (=1) | 0.0080 (0.0101) |

| Gender, Male (=1) | 0.0258 *** (0.0104) |

| Log Age of the respondent | 0.2171 *** (0.0173) |

| Primary level (=1) | 0.0030 (0.0142) |

| Secondary level (=1) | 0.0027 (0.0135) |

| University level (=1) | 0.1716 *** (0.0329) |

| Pre-existing conditions (=1) | 0.6006 *** (8.46) |

| Log Household size | −0.1365 *** (0.0173) |

| HFVI_predicted residual | 0.3113 *** (0.0182) |

| Interaction of HFVI with predicted residual | −0.0001 (0.0001) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muriithi, M.; Oleche, M.; Kiarie, F.; Mwangi, T. Healthcare Financing Vulnerability and Service Utilization in Kenya During the COVID-19 Pandemic, with a Focus on Policies to Protect Human Capital. Economies 2025, 13, 242. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13080242

Muriithi M, Oleche M, Kiarie F, Mwangi T. Healthcare Financing Vulnerability and Service Utilization in Kenya During the COVID-19 Pandemic, with a Focus on Policies to Protect Human Capital. Economies. 2025; 13(8):242. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13080242

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuriithi, Moses, Martine Oleche, Francis Kiarie, and Tabitha Mwangi. 2025. "Healthcare Financing Vulnerability and Service Utilization in Kenya During the COVID-19 Pandemic, with a Focus on Policies to Protect Human Capital" Economies 13, no. 8: 242. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13080242

APA StyleMuriithi, M., Oleche, M., Kiarie, F., & Mwangi, T. (2025). Healthcare Financing Vulnerability and Service Utilization in Kenya During the COVID-19 Pandemic, with a Focus on Policies to Protect Human Capital. Economies, 13(8), 242. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13080242