1. Introduction

This research emphasizes the importance of solidarity finance in the development of marginalized communities through financial inclusion and access to community microcredits. The commercialization of microfinance has driven its global expansion, but without adequate regulation, it has sometimes resulted in serious negative impacts on low-income borrowers. A prominent case is the 2010 microfinance crisis in India, where aggressive lending practices and insufficient oversight led to widespread borrower over-indebtedness and associated social distress. This example highlights the global relevance of our research and the necessity for responsible scaling in the sector (

Román Alarcón, 2018). This trend stands in contrast to the original goals of financial inclusion and access to community-based microcredit, which aim to empower marginalized populations and foster equitable development (

Pucha & Ferrer, 2024). Such initiatives foster community cooperation and provide opportunities for individuals traditionally excluded from conventional banking systems. Evidence suggests that microcredits delivered through solidarity finance mechanisms, when accompanied by training and technical support, can enhance the long-term economic sustainability of beneficiaries, contributing to increased household income and an improved quality of life (

Sangueza, 2019).

Despite financial and sustainability challenges, these alternatives have proven to be effective catalysts for local development and strengthening of financial capabilities. The political, social, economic, and environmental dimensions of solidarity finance are intertwined and constitute a collective contribution. These initiatives aim to promote community financial infrastructure. As highlighted by

Mejía et al. (

2020) “solidarity economy aims to incorporate universal values into the management of economic activity that should govern society and relations among all citizens: equity, justice, economic fraternity, social solidarity, and direct democracy.” Community social actors possess distinctive modes of interaction that are separate from the market economy and guided by shared values and practicing cooperative principles. Communities are organized through the collaborative efforts of both men and women, with their economic and financial relationships rooted in the principles of social and solidarity economy.

This predisposition is founded on the connection with the environment and the surroundings, where production is accompanied by a spirit of cooperation and equitable distribution. In this context, an observation by

Montalvo (

2020) suggests that the establishment of these alternative forms of local financial organization, initiated through self-management, enables social integration, fosters cooperative culture, and strengthens the pillars of commitment, trust, and social engagement. This underscores the cooperative principles associated with the foundation of a solidarity-based economy. On the other hand,

Medina (

2018) highlight that popular and solidarity finances constitute a new financial structure that serves low-income sectors who have been excluded from traditional banking financing and who operate in a spirit of solidarity. Such exclusion from the community social fabric places microcredits within the reach of these communities, making finance accessible to them. Microcredit should be viewed as part of a broader set of instruments aimed at supporting the creation, strengthening, and sustainability of beneficiary economic units (

Guerrero, 2023). If we focus on microcredit, it has had moderate effects, but not always the transformative effects that were initially expected, because the effects of microcredit depend on the individual characteristics of the borrowers (

De Mariz et al., 2011).

In rural areas, community funds represent an important contribution to the growth and organization of a popular and solidarity economy. After the enactment of the Law of Popular and Solidarity Economy local governments have promoted in their plans and policies the organization of community funds that take monthly contributions from their partners. These loans are microcredits, and these organizations are of importance in local development; by handling financial management, they become agents of change that help each other to achieve rural wellbeing, without having to go to a bank. The difficulty of accessing banks, in addition to the costs of credit, makes the use of banks impossible. In turn, the activities of these funds are focused on their organization, the achievement of objectives, financial management, accounting, tax, and marketing; this set of factors makes them productive.

The work of

Sánchez de Pablo and Jiménez Estévez (

2010), points out that there is a consensus in the cooperative literature regarding the association of the commitment of an organization’s members with a better financial performance of that organization. When members of savings banks become members of a local financial organization, they acquire a link that allows them to meet the financial objectives of the organization. The author in

Iturriaga (

2021) note that it is important that “the communities implement diverse practices for decision-making, where the collective interest must prevail”. These practices are based on their experiences and there may be tensions to resolve, but the collective interest of the organization in managing conflicts predominates.

Salinas and Saster Merino (

2021) emphasize that these organizations differ from conventional finance by prioritizing democratic participation and economic sustainability. Their financial practices are culturally embedded and tailored to members’ needs, aiming to legitimize inclusive decision-making and adapt to local social contexts (

Mejía et al., 2020).

Community funds emphasize equal democratic participation, enabling decisions that benefit the community and promote sustainability. Their financial products, mainly small loans, are tailored to the specific needs of members’ rural agricultural activities.

Montalvo (

2020) argues that popular and solidarity finance institutions function beyond financial access, serving as tools for social integration. They reinforce collective identity and autonomy, promoting values centered on mutual benefit and community cohesion.

The participation of the community allows the union of its partners to maintain a solidary position that facilitates social integration, through which attitudes of trust are created. Subsequently, behaviors are generated based on cooperation as a process of self-management, the related activities of which strengthen the organizations in terms of administrative and financial culture. This study highlights the intrinsic relationship of the principles expressed in the Law of Popular and Solidarity Economy with the elements of cooperative management and the organization of community funds in Ecuador. It also aims to evaluate the action in the following dimensions of these organizations: (i) associativity, (ii) autonomy, (iii) self-management, (iv) solidarity, and (v) organization management.

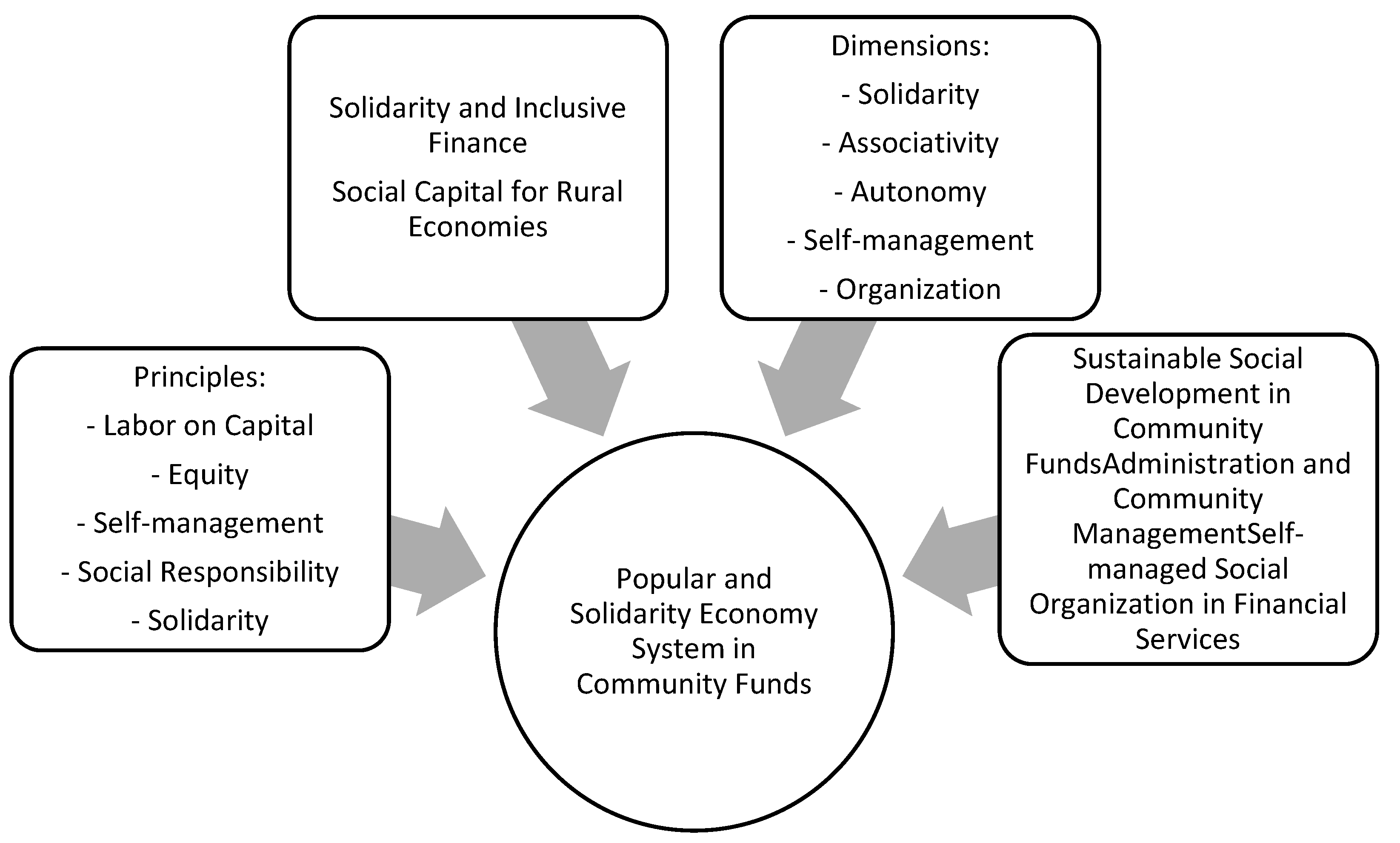

In the

Figure 1. This study addresses a significant gap in the literature on solidarity finance by examining its role in promoting sustainable local development and financial inclusion in marginalized rural communities in Ecuador. Previous research has demonstrated the theoretical potential of solidarity-based financial systems. However, a notable shortcoming is the lack of studies that have provided quantitative evidence on the organizational dynamics, internal governance, and sustainability outcomes of such systems. This research focuses on community funds as grassroots financial institutions and uses primary data collected from 51 organizations to analyze the influence of principles such as associativity (collaboration) and self-management on their performance. By establishing a correlation between these dimensions and perceived institutional strengths and weaknesses, the study sheds light on operational challenges and strategic opportunities for enhancing the long-term viability of solidarity finance in rural areas.

2. Theoretical Framework, Research Objectives, and Hypotheses

2.1. Community Funds in Ecuador

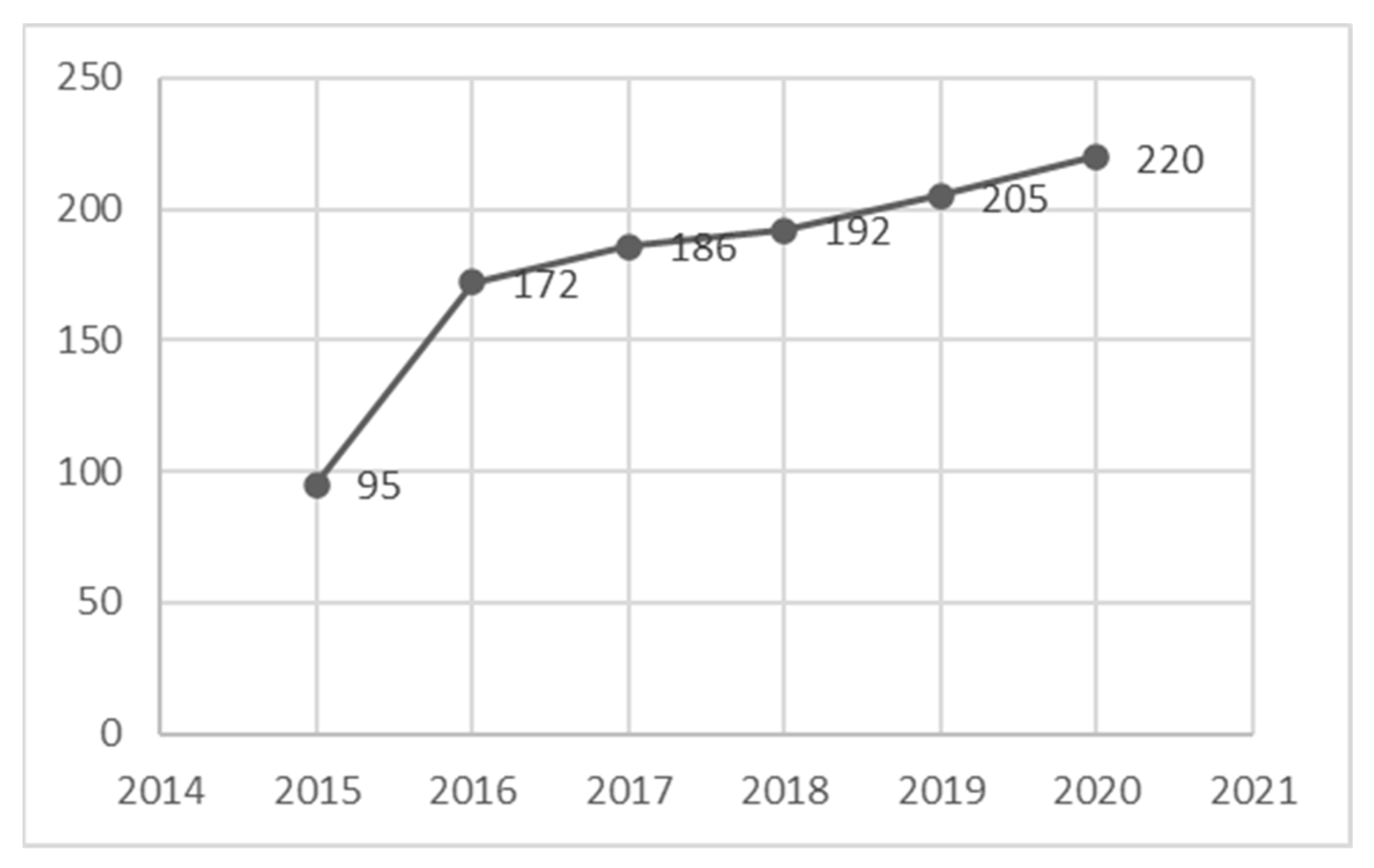

The development of the Law of Popular and Solidarity Economy (PSE) enables local governments and public institutions to generate policies related to the practice of this type of economy. In this regard, the prefecture a public entity that operates in rural sectors and has competences in rural productive development, established by the Directorate of Popular and Solidarity Economy. It trains and organizes community funds in the rural sector of Pichincha, focusing on its functioning as an activity that is part of rural economic development. The objective is to promote solidarity finance as a component of alternative financial support that replaces traditional credits. The number of registered community funds is depicted below.

Figure 2 shows the increase in community funds from the year 2015 onwards, which is related to their creation and promotion in communities through the principle of associativity. Community funds are registered in the registry of the Superintendency of Popular and Solidarity Economy (SPSE) in order to be in operation.

2.2. Principles of Popular and Solidarity Economy

Since the Law of Popular and Solidarity Economy (PSE) was enacted, the prefecture has issued public policies in its strategic plan that strengthen and promote the community financial system under the premise of achieving local rural development. These actions consider the principles of the PSE, as expressed in the Constitution of the Republic of Ecuador Art. 283, which defines the economic system as “social and solidary”.

Superintendencia de Economía Popular y Solidaria (

2012) recognizes organizations of this type of economy as the engine of the country’s development, and their principles promote cooperation, participatory democracy, and solidarity in economic activities. In relation to the cooperative principles for the community funds of the popular and solidarity financial sector (PSFS), they are guided by leaving aside individual interests and emphasizing work over capital, as well as gender equity, self-management, social responsibility, and solidarity. A popular and solidarity economy is based on the cooperation and solidarity of such activities. To create economic benefits that favor their needs, part of this organization uses community funds as a mechanism that allows for the promotion of savings by means of contributions that help partners with accessible and opportune credits, which allows them to improve their production.

In

Table 1, the relationship between the principles of the Popular and Solidarity Economy Financial System (PPSEFS) and the dimensions where associativity is prioritized is presented. Associativity is a way of grouping in a communal manner within a territory, depending on interests, establishing productive and commercial networks of products. Another dimension is self-management; when a communal account is already established, the strategy of the partners is to seek the greatest amount of benefits. Coordination between prioritizing labor over capital and collective interests over individual ones allows the community to establish this type of organization of economic resources, enabling active solidarity from each member of these community funds.

On the other hand, the principle of fair trade and ethical and responsible consumption implies a great capacity for association and, consequently, for the respective autonomy and self-management of individuals previously included in this type of economic grouping. Autonomy is fundamental in the exercise of any economic activity, and it is linked to gender equity, which facilitates associativity and organization, with subsequent respect for cultural equity, which leads to self-management and organization.

However, the need for training on recording knowledge in administrative and financial management so that the microcredit process can function must be emphasized, and it should be delivered in a democratic, transparent, and inclusive manner. Related to the previous dimension is autonomy; individual actions play a fundamental role in executing resources through decision-making without depending on any institution, and the financial management of these resources is characterized by independence.

Another dimension is solidarity, referring to mutual support in the administration of the financial organization so that surplus credits are reused in the same financial organization and so that obtaining resources is equitable. The last dimension is related to organization; in this case, activities are distributed between men and women, who manage resources not only individually but also for the wellbeing of all partners.

2.3. Community Social Development Through Community Funds

The majority of the population in rural areas has limited financial resources which do not satisfy their basic needs. Activities in rural areas are focused on agriculture and livestock farming, and the trade of agricultural products and household chores are part of the daily life of this population. Citizens of rural areas manage a type of financial organization in which the initial funds come from the contributions of the partners, who accumulate a social investment that gives them the opportunity to participate in rural development.

Valentin Mballa (

2017) the author highlights that “The role assigned to it by public policies in the strategy to combat unemployment and social exclusion”, i.e., the creation of employment and income without conditions of exclusion, are part of this type of policy. Therefore, promoting community funds is a way to ensure that this type of public policy fulfills its role; gaining access to microcredits without so many requirements is a valid action toward community development.

2.4. Functional Dynamics of Community Funds

Community funds operate as part of the national cooperative system of Ecuador—the Superintendence of the PSE—under a legal registry based on the number of partners and statutes that conform with the requirements of the administration and surveillance councils, as well as a credit committee which approves the authorization of applications for microcredits. According to

Medina (

2018), these organizations offer a critical alternative to capitalism, fostering collective values and democratic structures adapted to diverse local contexts. The actions used for managing community funds are part of a cooperative at a global level. Each country has its own regulatory framework and establishes a different socio-economic model to be used in its communities.

De Mariz (

2022), the author points out that “The belief that poverty can be addressed simply by providing credit to poor people has fueled the commercialization of microfinance”. Programs undertaken by state institutions can harm low-income people in communities because they are poorly educated. Many members of community funds work to market their products, saving money until the end of the month to pay their microcredit quotas, and few have the time to meet, train, and undertake solidarity actions. The risk that they do not pay their credit quotas becomes an individual condition, which requires assistance and motivation to build confidence. The same author points out that “Technical assistance, training and other support are fundamental. To achieve this, it is essential to have expert and adequately trained personnel who can help micro entrepreneurs”, and for this reason, local governments participate in training and guidance in financial management.

2.5. Elements of Management in Community Funds

A new strategy for promoting savings and boosting credit for the benefit of rural communities in the province is the organization of rural community funds with the aim of solving liquidity problems which cannot be solved via traditional banking. In

Midgley (

2014), the author notes that “Microfinance has ceased to be perceived as a quick solution to the problem of poverty”. Financial activity, therefore, begins to experience difficulties in terms of loan repayments, and this is where the effectiveness of microfinance has weaknesses.

Therefore, to be successful in financial activity, technical assistance and training must be available to help communities that carry out such financial practices to build trust among partners, to organize finances in a supportive manner, and to self-manage resources. For such an operation, an association is established between the community and the adequate management of community leaders; a position of “social” management is thus established. According to

Urretabizkaia and Fernñandez-Villa (

2015) the authors emphasize that “Their goal is social and supportive, as they prioritize work over accumulation and money”; that is to say, the organization promotes its activities with solidary purposes, thereby promoting the work of its members.

Community funds work with an intangible goal: the trust of partners. Honesty is part of the administration of such organizations, and internal rules and regulations are established both to define the contributions and to grant loans to beneficiaries. Quoting

Serigati and Furquim de Azevedo (

2013) the authors emphasize that “When a cooperative agreement is related to access and acquisition of knowledge, it requires an important level of trust and commitment among the partners”. To these ends, the delegates of the funds must specify the objectives of the organization. Therefore, the initial stage of this type of agreement is crucial, and leaders must establish the basis of operation under a statute that will be respected by all.

2.6. Solidarity Financial Management

Financial activity is a way to obtain microcredit through a financial product managed by community representatives, providing fundamental support that strengthens the work in the community. This activity meets the high requirements of local banking through the inclusion of solidarity, which creates certain conditions for local development in a sustainable manner. In this regard,

Soto Gorrotxategi et al. (

2021) highlights “Its potential to contribute to the generation of employment, social inclusion, and the development of their communities”, suggesting that such funds help communities generate work.

The managers of this type of finance are representatives elected among their associated partners. Quoting

Quiñones and Sunimal (

2003), the authors describe “The production, reproduction, and accumulation of social capital that give rise to social representations and values such as solidarity, reciprocity, and cooperation”. Such responsibilities guide financial activity and are framed by the trust of the leaders. The associated actions in the management of community funds in rural areas highlight a new form of financial structure. According to

A. Rodríguez and Donantez (

2016), the authors describe the “increase in financial deepening, above all, via financial inclusion and financial education”, which suggests that financial inclusion is promoted through this association, and for financial structures to operate in an orderly, legal, and ethical manner, the contribution of the involved partners is fundamental.

In this sense, within community fund management, self-management is practiced in which members actively participate in the decisions of the community organization and decide on its regulation and operation. This community effort to seek solutions to the credit needs of the community promotes the voluntary organization and dynamic action of its members, as described by

Jurado (

2017), pointing to these “new tendencies of massive and self-managed participation by the citizenship”. The practice of community financial activities leads to the solidary support of the members, taking responsibility under a regulation that looks for viable alternatives for operation and growth.

Adopting an attitude of respect for partners’ actions and adopting a system of aid turns cooperators into beneficiaries of microcredit at convenient interest rates for local development. Solidarity is, therefore, a behavior practiced in the community, centered on reciprocity and the achievement of collective benefits. It focuses on adopting an attitude of detachment and respect toward others. The ability to operate in an orderly and legal manner with ethical values, such as responsibility, honesty, and the integrity of leaders, unites the wills of people with similar interests, thus allowing partners to collaborate by being punctual in their payments and with the commitment to use the money for works in the rural area.

Another element of these organizations is the autonomy granted to organizations by savings banks in independently managing their actions according to their rules and regulations. According to

Kasparian (

2020), the author points out that “first and second degree cooperative and mutual organizations possess the necessary autonomy to adapt policies to the needs of their territories, except for the content of training programs”. Such a position emphasizes that policies are adapted to the circumstances of these organizations through training and technical assistance, which provide technical support to community leaders to motivate, facilitate, promote, and strengthen community participation and organization.

Community cooperativism is a method of organization for mutual aid that is destined to improve the conditions of partners, who are sufficiently organized to save small monthly contributions. This allows them to establish a savings fund that will later be designated as a microcredit to cover the productive necessities and the consumption of the contributors. If a loan is paid within its term with the generated interests, another partner benefits, and this is carried out in a successive way such that the fund is not left unfinanced.

Community funds in rural areas work in a solidary and self-managed way in the provision of financial services, which they provide to their partners through associativity. Such financial actions constitute a social organization oriented toward managing financial aid to support beneficiaries under the objectives, strategies, and policies of a regulatory framework, highlighting community cooperativism as an alternative action of development. According to

Sanchis and Campos (

2018), the authors point out that there are “Non-profit methods to develop inclusive markets for low-income individuals”; that is to say, the spaces of participation are part of inclusive finances and contribute to the dynamics of the market, as well as to the local and cultural economy of each community.

Table 2 details the specific activities of the community funds in Pichincha.

Article 90 of the Regulations of the Law of Popular and Solidarity Economy states that community funds “are organizations that carry out their activities exclusively in precincts, communities, neighborhoods or localities in which they are constituted and can be financed with their own resources” (

Auquilla et al., 2019). Therefore, these organizations operate with the contribution of resources from members who generally have little training in organization and financial management.

2.7. Social Capital

In rural communities, a significant aspect of social identity, the defense of their rights, and inclusion lies within social capital. It forms an integral part of community members’ experiences, encompassing participation in decision-making, trust, and commitment. These factors are driven by “social interactions that are fundamental to solving some of their problems; the sense of cooperation begins to grow as their actions intensify, and in this context, social capital increases or decreases as social integration fades away” (

Salinas & Saster Merino, 2021). On the other hand, rural community members, upon realizing their historical exclusion by traditional financial institutions, “promote social participation, opt for more sustainable development, and engage in sectors or activities that other capitalist enterprises reject due to lack of economic profitability, but that can serve a great social purpose” (

Ault, 2016). This is because their cooperative ties are strong, thereby solidifying financial sustainability. A conclusion made by

Quiñones and Sunimal (

2003) underscores that for solidarity financial institutions, identifying social capital means not monetizing their service provision process; this kind of cordiality is intrinsic to solidarity.

2.8. Economic Theory and Public Policies

The application of social and solidarity economy principles stems from the impetus of Keynesian interventionist public policy, which “proposed setting the objective to combat economic fluctuations” (

Gil, 2015). In the present context, such circumstances have their inconsistencies and limitations. In fact, labor, financial, and tax legislations become decisive and interventionist even within liberal systems (

Luque & Peñaherrera, 2021). These policies curb the extent of the economic cycle and view economic problems as imbalances within state budgets. A standpoint presented by

Luque et al. (

2019) acknowledge that “public policies act as the bridge between Civil Society and the State, thus translating into the responsibility of solving social problems.” One approach to promoting actions under the deficient conditions of poverty and inclusion faced by rural farmers is through fiscal policies implemented in various development plans that are aimed at being executed by different state institutions. A recurrent assertion developed by community savings institutions is that “the State can be a potent means of generating associativism within territories” (

Castelao Caruaca, 2016). Such action has become customary within communities to prompt the State’s concern for their issues. Consequently, community savings institutions serve as a reflection of policy implementation.

Due to poverty and various crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, rural communities have observed that orthodox models do not provide solutions to their challenges. Consequently, their social action seeks an alternative path, such as solidarity-based initiatives that prioritize participation and depart from individualism. These alternatives transform and build sustainable development relationships. “It is important to note that understanding cultural, social, geographical, ecological, territorial, and other aspects are central when proposing alternatives to orthodox models” (

Caballero, 2015). These new forms of community action promote community funds and leverage relationships to achieve equity and sustainability in marginalized populations.

2.9. Inclusive Finance

In rural sectors, the use of finances in an inclusive manner is intrinsic to the functioning of community savings institutions. Their administrative and financial management relies on its members, who apply social principles. While financing is essential, a pivotal role is played by an intangible element: trust. It becomes a key behavior for members seeking credit. In this position, community members ensure the repayment of their credit, thereby transforming this financial service into a driver of productive development. Future behavior is influenced by certain interrelations between members, constituting a part of financial management. Financial inclusion, in its broadest sense, is defined as the commitment to ensuring that individuals and businesses have access to useful and affordable financial services, including bank accounts, credit, and insurance. The promotion of financial inclusion has been shown to be a catalyst for economic and social development (

R. Rodríguez, 2018). They view money as a tool that transcends mere ends and becomes a means to pursue community objectives. This confluence of ideas “interconnects values of human dignity, solidarity, ecological sustainability, social justice, and democracy with interest or contact groups” (

Sanchis & Campos, 2018). These elements aim to position sustainable finance as a collaborative behavior to secure financing and, consequently, to responsibly make one’s monthly contributions and financial obligations.

The objective of this study is to understand how community principles influence community cooperatives and to determine the significant differences and homogeneity that exist between each of the studied groups due to variation in these principles. We propose the following hypotheses:

H0. The average response across the five groups is equal for all.

H1. There is a difference in the average response for at least one of the five groups.

3. Methodology

This study employs an exploratory quantitative approach and reports on a survey conducted on 51 community fund leaders in Ecuador. A convenience sampling method was applied to a pool of 220 funds in Ecuador. To assess reliability, Cronbach’s alpha was used. This statistical measure evaluates the internal consistency of survey items and indicates their effectiveness in measuring the same concept. The analysis procedure resulted in a high value of 0.959, suggesting high reliability and a significant correlation between items, calculated by superimposing indices.

3.1. Data Collection

The scales used in the questionnaire and the main constructs were analyzed by 5 auditing professionals, ensuring the validation of the survey. The questionnaire consisted of a total of 25 questions. As the rural location of each participating community is distant from the capital city, Quito, the questionnaire was shared online through Google Forms and was self-administered by the respondents, who are community representatives. However, instructions and clarifications were provided over the phone.

3.2. Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using version 25 of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). For the descriptive analysis, a scale was used to evaluate the significance to each of the variables. This mixed-methods approach helps enhance the validity of the independent variable. Descriptive statistics were employed to establish a reference point or a scale against which the data of each of the studied variables could be compared and evaluated. Additionally, analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were conducted to test the hypotheses. Associativity was considered the independent variable, while self-management, autonomy, solidarity, and organization were the dependent variables.

Table 3 summarizes the high internal reliability of the scale applied, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.959 for 25 items.

Table 4 presents the technical research sheet summarizing the key characteristics of the survey conducted for this study.

To determine the relationship between the variables, a scale of interpretation was constructed. In it, the total values of the survey were used as a base, and the highest and lowest values were determined using the SPSS program (2.5). These values were obtained by transforming the variable product of the scale as determined with the following response options: Always (5); Almost Always (4); Frequently (3); Almost Never (2); and Never (1). The new target variable imbues a certain value with meaning, for which the results of the Likert scale were transformed based on a coding strategy for the scores obtained in the survey. Likewise, this new system of values allowed us to facilitate interpretation, for which we used the categories described below.

As summarized below, three measurement criteria were established: low, medium, and high. For each one, a range was established with the values previously found, and to establish the ranges, the lowest value was subtracted from the highest value, and the result was divided by the number of criteria previously established (3). The range obtained was determined using the statistical program via the visual grouping command.

Table 5 shows the construction of the transformed scale.

4. Results

In relation to the transformed variables, the results of each can be analyzed with a description of their behavior, which is given below.

4.1. Associativity

Associativity is understood as a cooperative mechanism among members of community funds, who are generally small rural producers, with the objective of obtaining benefits that support their activity.

As shown in

Table 6, which presents the measurement of associativity in regard to community funds, it is evident that 47.1% of the respondents gave a score at the medium level and 33.3% gave a score at the high level, while 17.6% gave a score of low; this reflects that this variable is significant when grouping the medium and high positions, and that associativity is a driver of cooperative activities. These results are affirmed by

Maldovan Bonelli (

2012), who states that “The creation of associative entities, commonly established as cooperatives, has been a collective strategy that has enabled the improvement of working conditions in the sector, based on its recognition as a labor entity”. This strategy facilitates improvements in labor activities as a way of working together to achieve community-driven goals.

4.2. Self-Management

This variable allows members to carry out different activities to improve their income and to promote the operation of the community organization to fulfill social purposes, whose actions facilitate their own development.

As shown in

Table 7, this variable is significant when grouping the medium (43.1%) and high (29.4%) positions. With self-management, the community organization takes the task of solving the needs of the community into its own hands, and both its responsibilities and activities are regulated by means of a regulation created for the management of the community funds, in which administration, surveillance, and credit councils stand out. The latter oversees the qualification of credit approval and the distribution of the financial product, as discussed by

Vargas et al. (

2020), who state “The self-management advocates the direct and democratic management of the workers, in the entrepreneurial functions of planning, direction and execution”. These elements are present in community funds, whereby partners are empowered to qualify and apply for loans, which impels the use of solidary finances in local communities.

4.3. Autonomy

This variable represents the possibility that partners accept the responsibility to work voluntarily, and by accepting their obligations in a certain way, they function independently in the management of the financial organization.

For this variable, the following results were obtained: 56.9% of the respondents gave a score at the medium level and 29.4% gave a score at the low level, whereas 11.8% gave a score at the high level (see

Table 8). If we consider the results with medium and low scores, the community funds are not managed with autonomy and independence. They have the capacity of self-government and are democratically controlled by their members; however, the conditions to fulfill this principle depend on the contributions of the partners, and the decision-making process depends on the administrative council and the surveillance council. This means that members do not act with independence and are influenced by the actions of their managers, and not of their partners. According to

Olmedo et al. (

2016) the authors state “The expansion of economic opportunities is a fundamental pillar of women’s economic empowerment and, through it, the fight against poverty”. By obtaining a loan without further requirements, members can improve their conditions by eliminating the uncertainty of not having an income and can use these funds to ensure their family’s wellbeing.

4.4. Solidarity

For this variable, members have the right to access credits in a programmed way, and, at the same time, they are owners of the financial organization. Members are united by common interests, which include social and family ties, as well as by their mutual goals.

This variable is significant when grouping the medium-level (43.1%) and low-level (31.4%) scores (see

Table 9), which are unfavorable, while only 19.6% of the respondents gave a high-level score, indicating that solidarity—considered a basic principle of cooperativism that promotes the union of partners to meet financing needs—has failed to consolidate, resulting in insufficient mutual aid and a lack of support for each other in solving the financial problems of members. According to

Coba et al. (

2020), the authors highlight that “Greater economic participation of the members and appropriate programs to assist the community through compliance with laws, environmental care, respect, and social aid positively influence the results of cooperatives”. In other words, the greater the participation of the members, the more this has an impact on their results. This distinctive feature of these organizations is based on the solidarity and equal participation of the members, a situation that is being neglected.

4.5. Organization Management

Organization management is fundamental to the success and failure of its partners; therefore, the participation of members in a rural area becomes a process, the provision of which is handled with agreements toward the achievement of the common good, along with a focus on cooperation and participation, in order to establish actions that facilitate solidarity in finance work and provide timely attention to partners.

As shown in

Table 10, it is evident that for 54.9% of the respondents, the organization management of the community funds is medium, while 25.5% consider it to be high, and the remaining 15.7% consider it to be low. If we group the medium and high responses, this variable is favorable because, according to its functioning, the regulation permits the members to use their microcredits. Income and cash outflows are registered based on the contributions of the partners, and capital is moved according to the needs of the partners, which is in alignment with community development objectives. The partners promote the financial product and there are collection mechanisms based on trust. According to

Bustamente (

2019), the author emphasizes “Work methods, which refers to the arrangements for organizing work”. These elements are considered in these organizations, and it is evident that they have a distribution of activities that, under the directive, fully comply with their aims.

4.6. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

An analysis of variance was conducted for the following variables: (1) associativity, (2) self-management; (3) autonomy, (4) solidarity, and (5) organization management. ANOVA was applied to examine whether significant differences existed between associativity and the other variables. The results are discussed below.

In the

Table 11, Levene’s test for the homogeneity of variances showed that the variances were equal; therefore, a parametric ANOVA test was used. The results of the test indicate that there is a significant difference in at least one of the groups in terms of the belief in associativity as a benefit for cooperative activities. This is inferred from the significance value (Sig.) of 0.044, which is lower than the commonly used threshold of 0.05. The mean square was used to calculate the F-value, which is 2.938 in this case. Given that the significance value is less than 0.05, we can conclude that there is statistical evidence to assert that significant differences exist in responses among the groups regarding associativity as a benefit for association activities. However, to determine the specific differences among the groups, a post hoc comparison analysis was conducted, with the results presented in

Table 12.

The multiple comparisons table presents the results regarding the belief in associativity as a benefit across different groups. It presents the average differences (mean differences) between pairs of groups, with the standard error values and associated significance (Sig.). Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences. Thus, between groups 2 and 5 (self-management and organization), the average difference is 1.333, with a standard error of 0.469. The significance value (p) is 0.007, indicating a statistically significant difference at a 95% confidence level (significance level of 0.05). The 95% confidence interval for the difference in means ranges from 0.39 to 2.28. Since the p-value is less than 0.05, this suggests that groups 2 and 5 significantly differ in their beliefs about the beneficial nature of associativity for association activities. Group 5 demonstrates a significantly higher belief compared to group 2.

On the other hand, between groups 4 and 5 (solidarity and organization), the average difference is −0.800, with a standard error of 0.375. The significance value (p) is 0.039, indicating a statistically significant difference at a 95% confidence level. The 95% confidence interval for the difference in means ranges from −1.56 to −0.04. As the p-value is less than 0.05, it can be concluded that groups 4 and 5 exhibit significant differences in their beliefs about the beneficial nature of associativity for association activities. Group 4 displays a significantly lower belief compared to group 5. These differences support the alternative hypothesis and suggest that the type of organization (self-management and solidarity) influences participants’ perceptions of the benefits of associativity in association activities.

5. Discussion

In this study’s results, factors such as associativity, self-management, and organizational management emerge as strengths of community funds, emphasizing democratic, egalitarian participation and economic sustainability by adapting financial products to local needs and contexts. This aligns with findings of

Montalvo (

2020). However, autonomy and solidarity are identified as weaknesses, contradicting

Mejía et al. (

2020), assertion that these processes promote social integration, strengthening group bonds and identification with values oriented toward collective benefit and group autonomy. A significant strategy is that community funds represent an important option due to rapid cultural, social, and economic transformations, necessitating a deeper focus on community-oriented policies and a new design for social wellbeing. In this sense, the efficient use of financial resources becomes essential to ensure that these initiatives generate sustainable and impactful investment outcomes (

Li et al., 2023).

Community funds, despite having an institutional framework, vary from one country to another but represent an alternative socio-economic model. According to

Valentin Mballa (

2017), the author emphasizes that “Local development and microfinance are fundamental tools to meet the socioeconomic needs of individuals and therefore both realities are conceived as tools for the empowerment of endogenous capacities”. In other words, local development and microfinance are key to strengthening endogenous socio-economic capacities.

If we consider the principles expressed in the Ecuadorian PSE, we can observe their relationship with the dimensions of community funds. According to

Luque et al. (

2019), the author highlights that “It is complex for these organizations to preserve their principles, as they do not have the capacity to self-finance their activity”. Members of organizations practice principles that are related to those of financial cooperatives. Within the management of these organizations, the following traits stand out: associativity, autonomy, self-management, solidarity, and organization management. In the measurement of the mentioned dimensions, it is evident that solidarity finances are fulfilled through their actions in all the variables previously identified. Likewise, it is observed that there are two variables, autonomy and solidarity, that become the backbone of cooperativism and that are considered unfavorable in the opinion of community representatives. According to

Luque and Peñaherrera (

2021), the authors point out that “The involvement of farmers in cooperatives was significantly influenced by the confidence instilled by their leaders”.

This is similarly suggested by

Caballero (

2015), who mentions that “Productive endeavors are structured around reciprocity, and diversifying activities becomes crucial for comprehensive processes in saving, consumption, production, and marketing, aiming to mitigate the organization’s vulnerability”; reciprocity and diversification are vital for resilient, multifaceted productive processes. In line with this, the use of credit by beneficiaries has been primarily directed toward productive investments, reflecting a clear commitment to income-generating activities and local economic development (

Sierra et al., 2024). This focus contributes significantly to the effectiveness of credit allocation processes, especially in sensitive sectors such as agriculture and livestock (

Asoma-Caiza et al., 2024).

A contrary idea is put forward by

Román Alarcón (

2018), who state that “The inadequate management of cooperatives, coupled with prevalent corruption among members, resulted in their decline and the subsequent failure of the majority”. This shows that for community banks to be sustainable, the principles of cooperativism must be promoted; these are elements present in financial organizations that are backed by trust and that allow for the development of communities. Communities organize through the collaborative efforts of both men and women, with their economic and financial relationships rooted in the principles of a social and solidarity economy. Rural financial services are dynamic and must be adaptable and sustainable to enhance local competitiveness by leveraging local trust and cooperation in rural areas to build community social capital.

This predisposition is founded on the connection with the environment and the surroundings, where production is accompanied by a spirit of cooperation and equitable distribution. In this context, an observation by

Olmedo et al. (

2016) suggest that “Local financial structures, self-managed, foster social integration, cooperative culture, commitment, trust, and social engagement foundations”. This underscores the cooperative principles associated with the foundation of a solidarity-based economy. On the other hand,

Caballero (

2015) highlights that “Solidarity finances create a novel structure, aiding marginalized sectors excluded from traditional banking, operating with solidarity.” Such exclusion from the community social fabric places microcredit within the reach of these communities, making finance accessible to them.

A key limitation of this study was the difficulty of accessing remote rural locations due to their geographic dispersion. Additionally, the absence of fixed meeting points among several community fund representatives restricted data collection and limited the representativeness of the sample. Future research could address these issues by using remote data collection methods or strengthening local partnerships to improve access to the field and increase the scope of the study.

6. Conclusions

This study concludes that associativity, self-management, and organizational capacity are perceived as institutional strengths in community funds, contributing positively to their sustainability. However, dimensions such as autonomy and solidarity received lower evaluations, indicating areas for strategic improvement. These findings underscore the relevance of internal governance to financial inclusion efforts. Nevertheless, limitations such as the small sample size, the inaccessibility of rural areas, and context-specific variability may affect the generalizability of results. Acknowledging these constraints enhances methodological transparency and encourages further research to validate and expand these insights.

Rural communities have developed cooperative or associative economies to foster solidarity finance. Supported by government institutions offering training and guidance, they promote, manage, and organize community funds. This operation adapts actions through partner governance and selects leaders to manage, administer, and organize funds. These leaders promote financial products, approve the qualification of beneficiaries, and distribute surpluses. Focusing on dimensions of community funds related to the PSE principles—associativity, self-management, autonomy, solidarity, and organization management—reveals that autonomy and solidarity are the deficient variables impacting cooperativism and sustainability. Strengthening them through training and activities generating change in the social reality is essential. Communities have established financing networks for partners while fully developing other dimensions like associativity, self-management, and organization management.

The ANOVA and post hoc test results support these conclusions. Significant differences between groups 2 and 5 (self-management and organization) and between groups 4 and 5 (solidarity and organization) are observed, highlighting group 5’s significantly greater belief in the benefits of associativity for association activities compared to group 2. Likewise, group 4 exhibits significantly lower belief compared to group 5. These differences support the alternative hypothesis and suggest that organizational types influence the perceptions of the benefits of associativity. In summary, this study underscores the relationship between the PSE principles and community fund management. Solidarity finance contributes to community development and sustainability, while the strength of the PSE dimensions varies. Strengthening autonomy and solidarity is critical to drive cooperativism and sustainability forward.

These results suggest the need to raise awareness about the benefits of associativity, promote solidarity, and implement microcredit policies. Further research into differences in the perceptions of associativity and solidarity is warranted. These inferences can guide community fund partners in promoting associativity and credit access, while policymakers can design more effective strategies for credit sustainability in rural areas.