Abstract

The Export-Led Growth Hypothesis (ELGH) posits that expanding exports drive long-run economic growth. While this has held true for several Asian economies, its effectiveness across African regional blocs remains underexplored. This study investigates the validity of ELGH in the East African Community (EAC) and Southern African Development Community (SADC), assessing whether exports significantly contribute to economic growth in these regions. The analysis covers 22 EAC and SADC economies from 1990 to 2022—regions marked by structural transformation efforts, trade liberalisation, and participation in the AfCFTA. A dynamic panel data model based on an augmented Cobb-Douglas production function is estimated using the System Generalised Method of Moments (System GMM) to address endogeneity and reverse causality. Granger causality tests supplement the analysis. Exports and technology significantly enhance GDP growth, while labour and FDI are statistically insignificant. Trade openness negatively affects growth, suggesting vulnerability to external shocks. A bidirectional Granger causality exists between exports and GDP. This study offers the first dynamic, bloc-level empirical evaluation of ELGH across EAC and SADC, incorporating trade-related interactions. Findings affirm ELGH’s relevance and stress the need for export diversification, technological upgrading, and institutional reform for sustained growth in Africa.

Keywords:

export-led growth hypothesis (ELGH); dynamic panel modelling; System Generalised Method of Moments (System GMM); EAC; SADC; export; trade openness JEL Classification:

F43; F14; F10; 047; 055

1. Introduction

The persistent quest for sustained economic growth has been described as a complex interaction involving several factors, including capital accumulation (both physical and human), trade, investment, income distribution, and even geographical characteristics (Uzuner et al., 2025; Carrasco & Tovar-García, 2021). Among these, the export-driven growth stands out as a compelling framework that posits export expansion as a primary driver of long-run economic growth, especially in developing economies (Fraser et al., 2020; Cherif & Hasanov, 2024). The direct result has been removing trade-impeding barriers by individual, or groups of economies bound by regional ties (Global Alliance for Trade Facilitation removes barriers to growth, World Economic Forum, 2025). Tang et al. (2023) noted that nations that rely on trade to drive their economies have made considerable strides in recent years to accelerate their growth. As a result, a few Asian countries have used this strategy since the 1960s to achieve tremendous economic success. These economies include Malaysia, Taiwan, South Korea, Hong Kong, Thailand, and, most notably, China and India (Ego, 2024). The success of these export-oriented Asian economies marks a pivotal moment in empirical research on the impact of exports on economic growth.

Altman (2003) proposed the export-led growth (ELG) theory as a product and industry life cycle theory component. This idea suggests that exporting needs to start a cycle of economic growth (Medina-Smith, 2001). Over time, economic development, knowledge-based information, and local demand change the domestic economy’s structure, pushing it toward exports and more technologically advanced enterprises. Exports that have improved through innovation fuel economic growth, as domestic consumer demand declines—Giles and Williams (2000) present evidence for this effect. Moreover, export and import activities comprise international trade and account for a portion of GDP. When export volume and value are increasing and the development process is moving forward, this could increase the economy’s overall revenue. This demonstrates that exports are the economic engine, especially in emerging and developing countries (Salvatore, 2004; Syarif, 2016).

Import substitution strategy adopted by developing nations after WWII resulted in suboptimal economic performance, and many nations began to reevaluate their plans for accelerating economic growth after WWII (Todaro & Smith, 2014; Cherif & Hasanov, 2024) According to proponents of the export-led theory and free trade, the import substitution theory is to blame for the protectionist measures the Latin American nations took. This policy underperformed their economies (Shirazi & Manap, 2005). By implementing stabilization and adjustment programs to resolve external imbalances, many developing countries had to strengthen their export-led orientation. Export promotion is believed to help less developed and developing nations address external imbalances and achieve economic recovery. The findings for developing and non-developing countries are still ambiguous despite the topic’s continued research interest. Some ground-breaking research has drawn criticism for promoting an outward-looking export promotion strategy that uses fictional econometric analysis with false hypothetical benchmarks (Medina-Smith, 2001). The widespread support for export expansion found in prior studies was underscored by the failure of protectionism to impose import limits, particularly for many developing nations.

Stephen and Obah Daddy (2017) explored the relationship between exports and economic growth to domestic economic advantages gained through participation in international markets, including resource reallocation, scale economies, and various effects on human capital development. Although export-related activities are considered a viable route to industrialisation and a significant driver of economic progress in underdeveloped nations, they are nevertheless highly favourable today (Stephen & Obah Daddy, 2017). Export promotion and outward-looking policies had already taken hold and gained widespread acceptance by economists and policymakers by the early 1980s. It gained widespread acceptance and was recognised by numerous economists from developing countries (Tyler, 1981; Balassa, 1985). As a result, some countries have started to implement export promotion programs to benefit from international trade. Furthermore, as noted by Gençtürk and Kotabe (2011), the usage of export promotion programs has evolved into a need and an irrefutable component in deciding how well a corporation succeeds in exports. As a result, the relationship determines how businesses engage in exporting.

Most African countries pursue an import substitution strategy (IS) following their independence from the colonial master (Geda, 2005). After a brief period, this strategy became utterly unattractive and failed for most African economies. The policy aims to be sound, focusing on achieving a measurable and significant expansion in the domestic economies of these African nations before transitioning to an export-oriented approach. However, it faced severe constraints, including a production gap and high public expenditure. Failure to develop the human capital required for policy sustainability also contributed to the failure of the IS strategy in Africa. This led to the transition to an export-led growth strategy in most cases. To increase its capacity for growth, South Africa launched the General Export Incentive Scheme (GEIS), an export promotion scheme, in 1990. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade’s export subsidies were consolidated and eventually eliminated owing to this mechanism, which took the role of earlier category schemes. The export promotion strategy justifies overcoming short-term growth barriers in the formal sector of the economy.

Consequently, dismantling trade restrictions such as quantitative restrictions, import duty imposition, and entrance into several bilateral and multilateral trade agreements became crucial in promoting seamless trade for better benefits. Merchandise exports grew by 18 percent between 2000 and 2008 as the economies of Africa opened up to trade. Similarly, the gross domestic product (GDP) also grew as exports grew. The GDP increased by an average of 6.2 percent between 2002 and 2008 (Songwe & Winkler, 2012).

Mengistae and Pattillo (2004) reported efficiency in the manufacturing sector with an export orientation in Ethiopia and Ghana. This reflects the diversity of the countries’ export sectors. Despite several years of effort on an export-led strategy, approximately 45 countries on the continent have yet to diversify in an actual sense, focusing mainly on primary products (UNCTAD, 2022a). Other components, such as trade-in services, are low. Services accounted for approximately 17 percent of export content from Africa between 2005 and 2019, with transport services and travel accounting for two-thirds of the service component (UNCTAD, 2022b). One of the challenges facing Africa’s resource-rich economies, such as Nigeria and Algeria, is diversifying production beyond the natural resource sector. Natural resource-based products have dominated exports for the past 50 years.

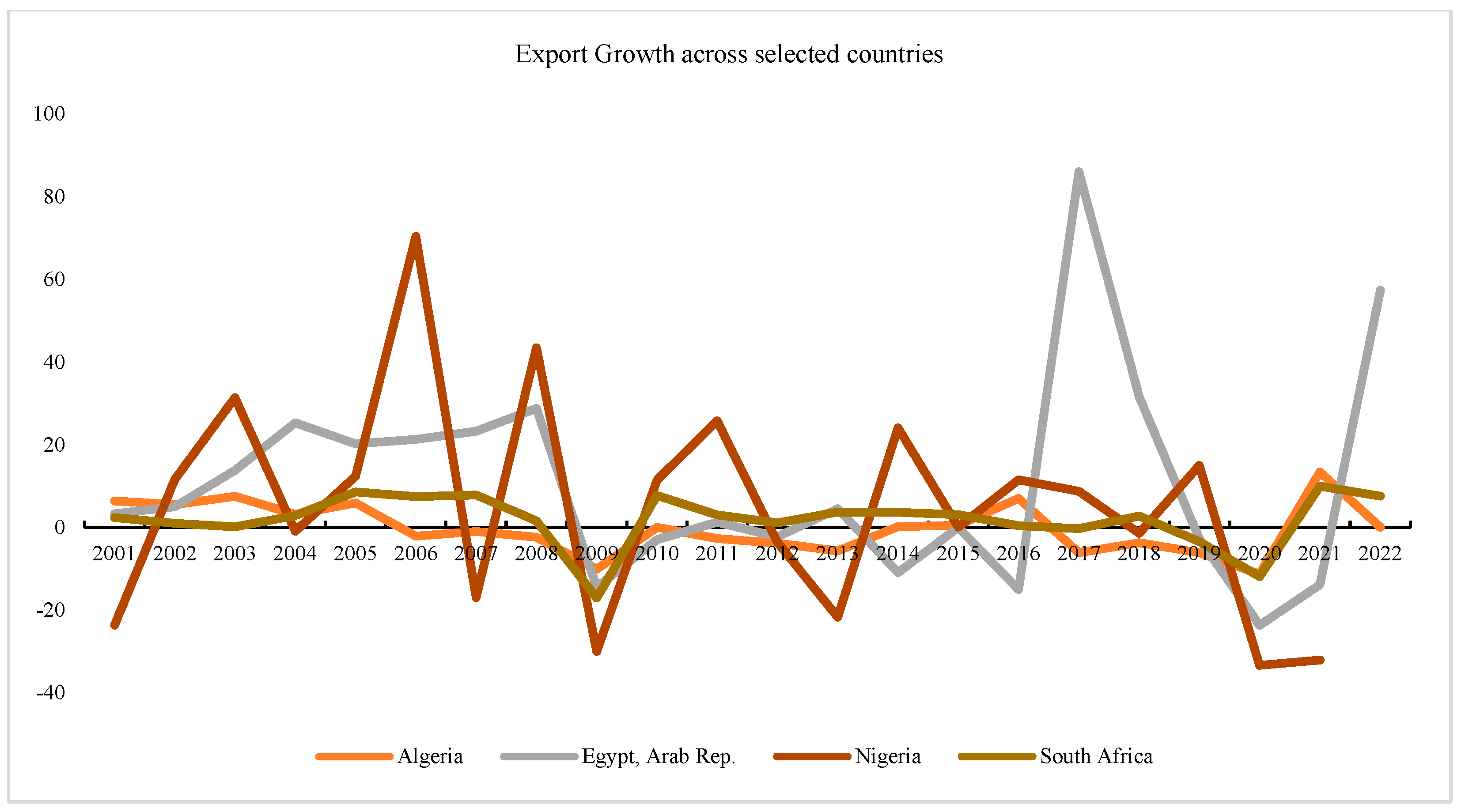

Figure 1 shows the growth pattern of exports in 10 countries from 1985 to 2022. There are noticeable seasonal and oscillatory fluctuations. Egypt experienced significant fluctuations, with steady growth from 2001 to 2008, followed by a sharp decline in 2009. Similarly, Algeria, Nigeria and South Africa faced negative export growth in 2009, mainly because of the impact of the 2008/2009 financial crisis. The impact of the 2008/2009 financial crisis caused these fluctuations. Most of these countries bounced back in 2010, and their export growth remained optimistic concerning policies and export development. Although there is empirical research on the importance of exports in developing nations, studies on the causal relationship between exports and economic growth from a panel perspective for the largest economies are scarce. Although many studies assume that exports play a crucial role in African economic growth, it remains essential to experimentally determine whether exports drive economic growth or if economic growth stimulates exports.

Figure 1.

Export growth across selected economies in Africa. Source: compiled from WDI data 2022.

While substantial empirical evidence supports this hypothesis, the context-specific validity of ELGH in African regional economic blocs—particularly the East African Community (EAC) and the Southern African Development Community (SADC)—remains underexplored. Previous studies, including the original focus on Africa’s major economic strength (e.g., Nigeria, South Africa, Egypt, Kenya), have revealed a positive relationship between exports and GDP growth (Ee, 2016; Medina-Smith, 2001). However, such analyses often aggregate country experiences without acknowledging the heterogeneity of trade structures, institutional capacities, and economic integration efforts across African regions (UNCTAD, 2022a).

The EAC and SADC represent critical regional blocs committed to deepening trade integration, yet differ significantly in terms of industrial development, export composition, and infrastructural capacity (Songwe & Winkler, 2012; B. Moyo, 2023; Chihaka, 2017). Furthermore, implementing the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) amplifies the urgency of generating bloc-specific empirical evidence to inform strategic export promotion policies (UNECA, 2018). Despite commitments to trade liberalisation and export diversification, most member countries within EAC and SADC remain heavily reliant on primary commodity exports, with minimal integration into global value chains (UNCTAD, 2022b). This export pattern raises questions about the sustainability of export-led growth in the absence of technological upgrading and human capital development (Hausmann et al., 2006; Grossman & Helpman, 1991).

Given these contextual realities, it becomes imperative to re-investigate the ELGH using a regional lens, moving beyond country-level generalisations to explore intra-bloc dynamics. Moreover, many African countries are implementing regional infrastructure corridors, common external tariffs, and trade facilitation measures, yet empirical assessments of their impact on growth via exports are lacking (Farahane & Heshmati, 2020). Hence, this study aims to empirically test the export-led growth hypothesis across the 22 economies with EAC and SADC. Our model builds on the augmented Cobb–Douglas production function proposed by Farahane and Heshmati (2020) using available data from 1990 to 2023 from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (World Bank, 2025).

From a methodological standpoint, many African trade-growth studies rely on static models such as fixed effects or pooled OLS, often ignoring endogeneity, dynamic feedback mechanisms, and measurement errors (Clark & Linzer, 2015). This study responds to such concerns by proposing a System Generalised Moment of Mean (Blundell & Bond, 1998), which is well-suited to panels with a moderate time dimension and many cross-sectional units.

2. Literature Review

The export-led growth hypothesis (ELGH) generally asserts that there is evidence of a positive relationship between exports and economic growth and that export expansion is one of the main drivers of economic growth (Medina-Smith, 2001; Cuaresma & Wörz, 2005). Several changes that have taken place in development and international economics during the past 20 years are the source of evidence for a rather large body of study on the connection between trade and growth. This progress illustrates the widespread switch from internally focused tactics to strategies that promote exports. Export-led growth theory holds that increased exports accelerate the economy due to the spillover of technical innovation and various externalities (Jordaan & Eita, 2007). As a result, the export-led growth hypothesis postulates that a rise in exports would result in gains in overall productivity and economic growth.

Following the decline in the global market for primary goods and the rise in the balance of payment deficits in developing countries’ current accounts in the 1950s and 1960s, the debate over the advantages of domestically focused strategies (import substitution) and export promotion in developing countries arose. Scholars have argued that market imperfections make it challenging for less developed and emerging countries to contend with and promote protectionism. As a result, fiscal revenue and savings are maintained domestically and used to support public spending and homegrown investment (Moritz, 1997). Second, Blomström and Hettne (1984) claimed that protectionism (import substitution) guarantees productivity through increased domestic investment and encourages self-sustained economic expansion. Initially, import substitution proved quite successful, with rapid growth in domestic output and industrial employment creation.

The necessity of increasing tariffs on intermediate and investment goods to preserve growth has resulted from the difficulties many nations face in the global market. This created a problem for the consumer goods industry since inconsistent global competition has reduced the competitiveness of local manufacturing structures. There is a widening disparity since the domestic cost of saving foreign currency through import substitution is greater than the resource cost of generating foreign currency through exports. Balassa (1985) presented an export promotion plan to solve these problems and enhance resource allocation, capacity utilisation, factor productivity, and employment possibilities for developing nations with labour-rich economies. This strategy also established small local markets, increasing export competitiveness and industrial efficiency. As industrialisation advances, competitive advantage grows, encouraging increased export growth. Jung and Marshall (1985) identified four links between trade and economic growth: pro-growth export expansion, pro-trade economic growth, anti-growth export promotion, and anti-trade economic growth. This bi-causal relationship is crucial for developing nations and emerging markets aiming to improve living standards through economic reform.

However, modelling the relationship between increased exports and growth is challenging because of the intricately intertwined components of GDP. Consumption, the most significant component of most EAC and SADC economies’ GDP, is driven primarily by domestic demand for goods. Export promotion increases domestic productive capacity, whereas consumption includes demand for imported items, potentially resulting in a negative net export balance. Helpman and Krugman (1985) acknowledged that international trade theory does not fully explain the relationship between trade and technical efficiency, with uncertainty in the effect of trade on technical efficiency under imperfect competition and increasing returns to scale. Export-led growth is a concept that is furthered by the concepts of export specialisation and the natural resource curse. Rehner et al. (2014) claim that the natural resource curse and export specialisation in just a few commodities reflect the typical manifestation of the early commodity-based “division of labour” between industrialised nations and their raw materials and primary product suppliers. According to Rehner et al. (2014), academics and politicians have regularly used the “dependency theory” and structuralism to analyse the relationship between development and raw materials in Latin America. The natural resource curse can potentially swallow nations such as Nigeria, which are focused on using oil exports to drive its economy.

Owing to the growth miracle of newly industrialized economies, several empirical studies have been conducted on the relationship between trade and growth. Currently, a plethora of time series studies concentrating on the link between exports/export expansion and growth or between trade orientation and growth have been carried out). Although several empirical studies confirm that a larger export share of GDP correlates with faster growth, some studies find an inverse relationship, whereas others remain inconclusive. The summary of some key studies in this regard is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of empirical/methodological reviews.

Theoretical Framework

The link between trade and economic growth has long been at the forefront of economic theory (Rebelo & Silva, 2017). The export-led growth hypothesis (ELGH) evolution began with classical economists like Adam Smith and David Ricardo, who laid the foundation. Smith argued that specialisation and division of labour, combined with trade, increased productivity and wealth. Ricardo’s theory on comparative advantage advanced this thinking by postulating that attaining production efficiency is based on specialisation. By implication, countries become efficient by specialising in their most comparative advantageous sector while trading for exchanging goods where others have a comparative advantage. This classical view underpinned early theories that framed export growth as a primary economic development engine.

The fundamental argument of the ELGH is that increasing exports expands market access beyond domestic boundaries, increases demand for domestic goods, enhances economies of scale, and improves overall productivity. These dynamics, in turn, promote job creation, investment, and economic expansion. Giles and Williams (2000) and Santos-Paulino (2000) noted that exports could open opportunities for domestic producers to improve efficiency through competition and technological adaptation, often stimulated by engagement with global markets.

However, classical and neoclassical theories, such as the Solow–Swan model, offered a more limited perspective by treating technological progress as an exogenous factor. In the Solow model, long-run economic growth is driven by capital accumulation, labour growth, and an exogenous rate of technological advancement. While the model introduced a robust framework for analysing savings and investment behaviour, it failed to account for how policy, innovation, or knowledge creation might influence growth dynamics directly.

In response to these limitations, Mankiw et al. (1992) extended the Solow model by incorporating human capital as an additional production factor, thereby formulating the “augmented Solow model.” This model proposed that economies with higher levels of human capital (education and skill acquisition) could experience faster growth rates than those with only capital and labour. The functional form of the augmented model reflected an augmented Cobb–Douglas production function, capturing the role of education and health in influencing productivity. However, even this advancement maintained the assumption of exogenous technological progress, which posed challenges in explaining why some countries grew faster than others despite similar initial conditions.

The emergence of Endogenous Growth Theory (EGT) in the late 1980s marked a dominant turnaround in growth economics. The theory, pioneered by Romer (1990) and Lucas (1988), assumed exogenous technological change. It argued that growth is driven by internal economic factors, such as human capital accumulation, innovation, research and development (R&D), and institutional quality. Endogenous models allow for sustained long-run growth through knowledge spillovers, increasing returns to scale, and learning-by-doing. These models emphasise that public policy and institutional frameworks are critical in shaping economic outcomes.

A critical feature of the endogenous growth theory is that it stresses the role of technological progress and knowledge as products of deliberate investment decisions. Moreover, Romer (1990) averred that non-rivalrous and partially excludable innovations could generate increasing returns, thereby fuelling sustained growth. Lucas (1988) highlighted the role of human capital and the external effects of education, which enhance productivity and economic performance. This theoretical orientation provides a more realistic and policy-relevant framework, particularly for developing economies where innovation systems and education infrastructure are in flux.

Trade openness plays a central role in the endogenous growth framework. According to Grossman and Helpman (1991), international trade enhances growth by facilitating access to advanced technologies, fostering innovation, and encouraging specialisation. Countries that open their markets are more likely to attract foreign direct investment (FDI), benefit from knowledge transfers, and improve the quality and diversity of domestic production. However, they also acknowledge that the effect of trade on growth is not automatic; it is conditional on the absorptive capacity of the domestic economy.

Recent empirical studies support these theoretical insights. Aghion et al. (2019) found that countries with stronger institutions and more robust human capital experienced greater benefits from trade openness, reinforcing the endogenous view that growth outcomes depend on internal capabilities. Similarly, Lee and Vu (2020) provided evidence from ASEAN countries showing that export sophistication and R&D spending are positively associated with total factor productivity (TFP) growth. These findings agree that trade-driven growth is most effective with strategic domestic investments.

In the African context, the limitations of the Solow-based models are particularly evident. Despite increasing their export capacity over the past few years, a few African economies still face debilitating challenges of slow industrialisation, sparse innovation, and low productivity. The findings of Sanni et al. (2019) underscore this paradox, showing that despite increased export volumes, structural challenges have constrained trade growth potential. Some manifest weak institutions, heavy dependence on primary products with low-value additions and a lack of state-of-the-art infrastructure.

On these grounds, the structuralist critique of trade liberalisation remains relevant. Deraniyagala and Fine (2001) argue that heavy reliance on trade at the detriment of expansion in the local productive sector leads to deindustrialisation, income inequality, and vulnerability to external shocks. This perspective aligns with the experiences of several Sub-Saharan African countries where trade openness has not translated into industrial upgrading or innovation-led growth.

Recent studies call for recalibrating export-led strategies to align with endogenous growth principles. Ajakaiye and Ncube (2010) emphasise the need for African countries to transition from raw commodity exports to knowledge-intensive industrialisation. They argue that policies fostering human capital, innovation, and institutional reform are essential for translating trade into long-term development. Bakari and Tiba (2020), analysing North African economies, also find that export growth has a limited impact on economic performance unless accompanied by improvements in governance and technological capacity.

The theoretical framework from this literature integrates trade, innovation, human capital, and institutional quality into a coherent endogenous growth model. The traditional Cobb–Douglas production function is augmented to reflect the multiple channels through which exports and trade openness can influence productivity. A general representation may be expressed as:

represents output, , physical capital, , labour, , human capital, , technology or innovation, and , trade openness or institutional quality. The term captures TFP, which is influenced by internal variables rather than external shocks in the endogenous growth setting.

In conclusion, while the classical and neoclassical models provided important insights into the role of exports in economic growth, they fall short of explaining long-term development dynamics. The endogenous growth framework offers a more comprehensive perspective by incorporating the internal mechanisms, such as innovation, education, and policy, that condition the impact of trade on growth. For developing countries, especially those in Africa, export-led strategies must be embedded within broader policies that enhance productive capacity, foster innovation, and build institutional resilience.

In the African context, the limitations of the Solow-based models are particularly evident. Many African economies have expanded their export base over the past decades but continue to experience slow industrialisation, limited innovation, and low productivity. The findings of Sanni et al. (2019) underscore this paradox, showing that despite increased export volumes, structural challenges have constrained trade growth potential. These include weak institutions, poor infrastructure, and heavy dependence on primary commodities with low-value additions.

Despite the robust theoretical and empirical work on export-led growth and endogenous growth theory, several critical gaps remain in the literature, particularly in the context of African economies. Many existing studies isolate export performance from total factor productivity without adequately modelling the interactive effects of trade, human capital, and technology in a unified framework. This study addresses this by employing a model that integrates these variables. Many empirical models use outdated datasets or fail to capture the dynamic nature of export-led growth using modern econometric techniques. By employing System GMM and dynamic panel modelling, this study provides updated and robust results that are useful for policymaking.

Despite the robust theoretical and empirical work on export-led growth and endogenous growth theory, several critical gaps remain in the literature, particularly in the context of African economies. Many existing studies isolate export performance from total factor productivity without adequately modelling the interactive effects of trade, human capital, and technology in a unified framework. This study addresses this gap in the literature by employing a model that integrates these variables. In addition, many empirical models use outdated datasets or fail to capture the dynamic nature of export-led growth (Ee, 2016; Odhiambo, 2022; Kollie, 2020; Biyase & Bonga-Bonga, 2014; Rangasamy, 2009) using modern econometric techniques. By employing System GMM and dynamic panel modelling, this study provides updated and robust results useful for policymaking.

3. Data and Methodology

In examining the Export-Led Growth Hypothesis (ELGH) across EAC and SADC countries from 1990 to 2022, this study adopts the System Generalised Method of Moments (System GMM) estimator developed by Blundell and Bond (1998). The selection of this estimation technique is underpinned by its superior capability to handle endogeneity, dynamic relationships, and persistent variables, which are common features in macroeconomic panel datasets.

The Cobb–Douglas production function in an augmented version, as in Equation (1), is respecified in Equation (2) below:

where the dependent variable is the output, which is a proxy for real gross domestic product (GDP); the left-hand side variables are the regressors or the independent variables, which are capital input (CAP); , which stands for labour input (LAB); , which represents technology (TECH); and , which is the vector that captures all trade-related variables that define the external sector. The Z vector incorporates the following elements: exports (EXP), foreign direct investments (FDI), the real effective exchange rate (REER), trade openness (OPS), total debt service (TDS), and terms of trade (TOT). m are the unknown model parameters, and is the multiplicative disturbance or error term. The above-specified Equation (1) is in its multiplicative exponential form. We linearize it to form a logarithmic function as specified below in Equation (2):

where the subscript i (=1, 2, 22) is the cross-sectional dimension that represents Angola, Botswana, Comoros, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Eswatini, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Seychelles, South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Uganda and Somalia, and the subscript t (=1, 2, 3) is the time series dimension that represents years. The residuals follow a one-way error component comprising time-invariant country effects and the random error term .

Table 2 captures nine continuous variables. The table also reveals a deflated figure for all monetarily measured variables with the help of GDP deflators (2010 = 100) from the respective data source. Notably, trade-related variables are the key variables of interest for this study, whereas the conventional endogenous growth function (Cobb–Douglas function) variables are the four factors of production (capital, labour, and technology) and are the control variables. From Table 2 and Equation (3), we include the variable log of Export as a measure of Export, this inclusion represents Foreign direct investment inflows, and “total debt service” is included in the model to capture debt overhang; we include the “log of absolute effective exchange rate index to capture distortion and variability in the exchange rate, and the “log of trade openness ( It is used to capture outward orientation and insufficient demand for primary products. Deterioration in terms of trade characterizes developing economies in general, including across the ten (10) countries considered for this study; hence, the “log of terms of trade” ().

Table 2.

List of variables.

According to conventional production theory, production variables should positively correlate with increasing output. We anticipate favourable developments for the marginal outputs of capital, labour, and technological inputs. Following the body of research on international commerce, we conducted this analysis under the presumption that increased exports, substantial foreign direct investment, and increased openness or outward orientation encourage growth. On the other hand, we further assumed that real exchange rate volatility and deteriorating trade terms constrain growth, considering the respective economic situations of the twenty-two (22) countries. Given these presumptions, we anticipated that the coefficients for exports, FDI, and trade openness would all have positive estimates. In addition, we also expected negatively signed estimates for the coefficients of the debt–income ratio, the real effective exchange rate index, and terms of trade. The model of the estimation was done using R version 4.2.2.

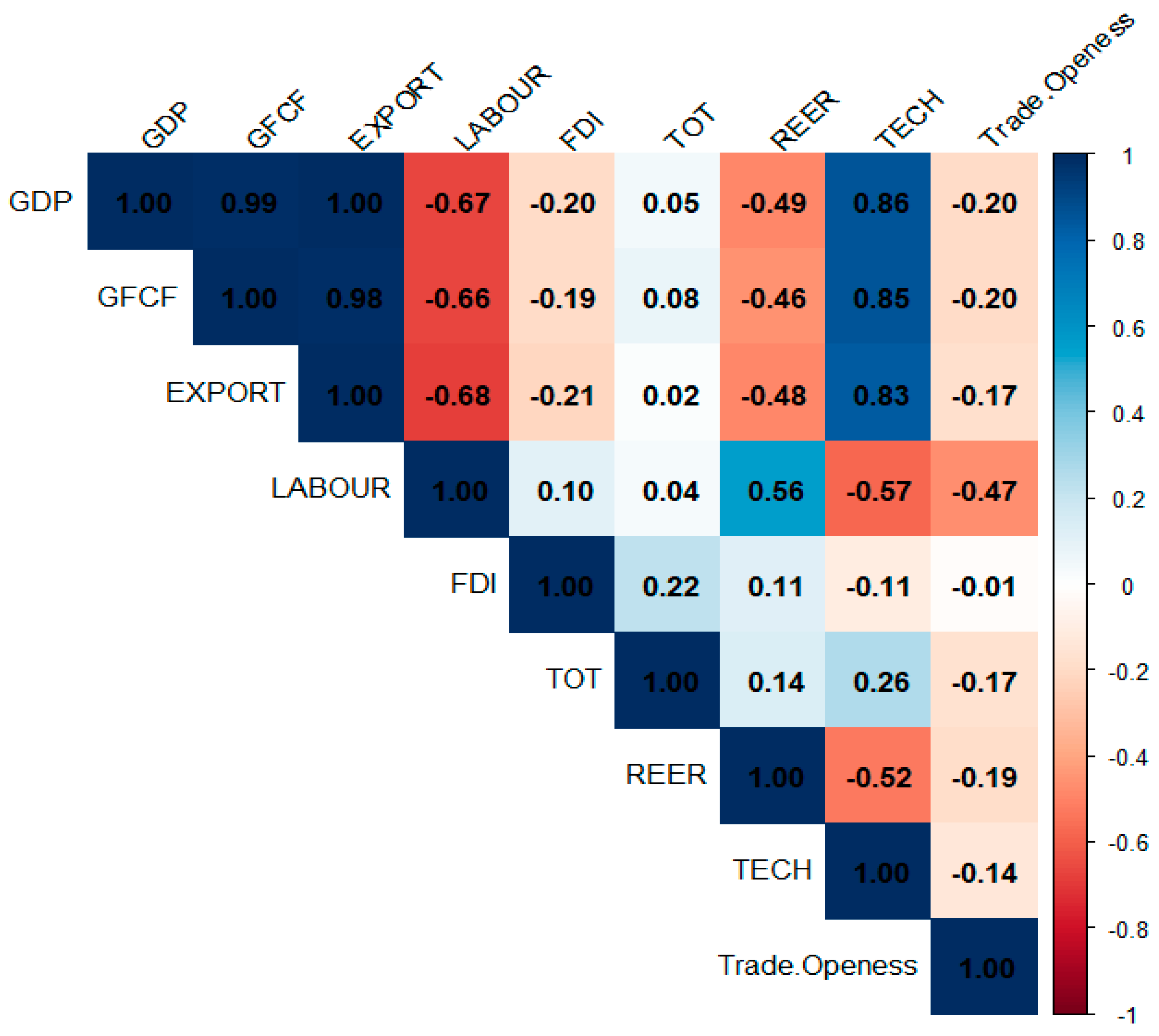

The correlation matrix in Figure 2 further reveals the relationship among the variables. The outcome of the correlation matrix reveals strong positive relationships between GDP, capital input (GFCF), exports, and technology, highlighting their joint role in driving economic growth, consistent with prior studies (Hordofa, 2023; Yeboah et al., 2025). Labour input across countries, however, has a negative correlation coefficient with these variables, suggesting shifts in labour productivity or economic structure during development (Romer, 1990). Foreign direct investment (FDI) and terms of trade show moderate positive links, while trade openness and real effective exchange rate (REER) negatively correlate with GDP and labour, which reflects rather complex trade and exchange rate dynamics. The strong export–technology correlation (0.83) underscores technology’s key role in enhancing competitiveness (Grossman & Helpman, 1991).

Figure 2.

Correlation matrix. Source: authors’ computation 2025.

These high correlations, especially among GDP, capital input, exports, and technology, raise concerns about multicollinearity, which can lead to biased regression results. Additionally, simultaneity and omitted variables pose endogeneity risks. The adoption of the System Generalised Method of Moments (System GMM) estimator in this study helps in controlling endogeneity and unobserved heterogeneity by using internal instruments derived from lagged variables (Arellano & Bover, 1995; Blundell & Bond, 1998). This method provides consistent, efficient estimates in dynamic panel settings, making it suitable for modelling economic growth determinants (Ullah & Akhtar, 2018).

In examining the Export-Led Growth Hypothesis (ELGH) across EAC and SADC countries from 1990 to 2022, this study adopts the System Generalised Method of Moments (System GMM) estimator developed by Blundell and Bond (1998). The selection of this estimation technique is underpinned by its superior capability to handle endogeneity, dynamic relationships, and persistent variables, which are standard features in macroeconomic panel datasets. All the estimation was done using R version 4.2.2. This study further describes the data based on the panel descriptive statistics as presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Panel descriptive statistics.

The descriptive statistics presented in Table 3 cover eight key macroeconomic variables: GDP, Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF), Exports, Labour Input, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), Terms of Trade (TOT), Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER), Technology (TECH), and Trade Openness. Most variables have significant variations, with sample sizes ranging from 236 to 729 observations. The data show considerable disparities, reflected in the wide ranges and high standard deviations predicated upon the varying size of the 22 economies captured (Bhandari, 2020). The wide dispersion observed in the case of technology also alludes to this. Countries such as South Africa, Tanzania, and Kenya rank far better in technological adoption than other countries within the EAC and SADC (World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), 2022). Moreover, this indicates the vast differences among countries in economic size, investment, trade, and technology levels over the period under consideration.

Consequently, seven of the eight variables exhibit positive skewness except for labour input, denoting that their distributions have long right tails. This further corroborates the measures of central tendency and variability. This pattern suggests that while many observations cluster around lower to moderate values, a few countries or years display extremely high values, such as large economies with massive GDPs or countries attracting significant foreign investment. Labour Input is the only variable with negative skewness, indicating a slight left tail and relatively more concentrated values near the higher end. These skewness patterns highlight economic heterogeneity among the various countries within the two regional blocs, where most economies are moderate in size and input, but a few dominate with very high values.

On the kurtosis, variables like GDP, Exports, FDI, REER, and Technology have values well above the normal distribution benchmark 3, indicating leptokurtic distributions. This means these variables have sharper peaks and heavier tails, with more frequent extreme values or outliers than a normal distribution would suggest. In contrast, Labour Input shows a flatter, platykurtic distribution with fewer extreme values. The presence of strong skewness and leptokurtosis in most variables suggests that economic data are prone to outliers and non-normality, which has important implications for modelling and analysis, often requiring data transformation or robust statistical methods to achieve reliable results.

A further respecification of the Equation (3) in the general form of dynamic panel specification is given below in Equation (4):

where

Given the persistence in GDP and the likelihood of reverse causality between exports and growth, the model is estimated using the System Generalised Method of Moments (System GMM):

- (countries in EAC and SADC)

- (years, e.g., 1990–2023)

- = country-specific effects

- = idiosyncratic error term

The macro panel model specified in Equation (5) contains a fixed effect requiring elimination. These represent time-invariant characteristics of each country that influence economic growth but are not captured by the explanatory variables, which can undermine the validity of the estimation outcome (Kripfganz & Schwarz, 2019).

Going by Blundell and Bond (1998), differencing Equation (4), the levels equation, instrumenting the levels equation using lagged first differences under stationarity assumptions ensures the elimination of the fixed effect.

This removes which is correlated with regressors, is thus respecified as below in Equation (6):

One of the fundamental econometric problems, endogeneity, could pose a serious challenge to the validity of empirical outcomes, leading to bias and inconsistent parameters (Wooldridge, 2010). As such, in the specified model, where economic growth (GDP) is assumed to be a function of capital , labour , technology , and external sector indicators such as exports , foreign direct investment , trade openness , real effective exchange rate , and terms of trade , a critical issue that may arise is endogeneity.

While exports can stimulate GDP growth through increased production and foreign exchange earnings, higher GDP growth levels can simultaneously increase export volumes by expanding domestic production capacity and improving international competitiveness (Awokuse, 2008). Thus, the endogeneity issue results from the reverse causality of exports on GDP. Therefore, the direction of causality may run both ways, violating the exogeneity assumption required for OLS. Similarly, studies have also revealed that while FDI inflows are often seen as a driver of growth through capital accumulation and technology transfer, they tend to flow into countries that already exhibit strong economic performance and growth potential (Mushi & Ahmed, 2025; Chowdhury & Mavrotas, 2006), indicating a feedback relationship between FDI and GDP.

Although real effective exchange rate (REER), which reflects a country’s price competitiveness in international markets, is most of the time treated as an exogenous determinant of trade performance and growth, empirical evidence suggests it is influenced by macroeconomic fundamentals such as inflation, interest rates, and fiscal balances, all of which all through dynamic interaction impact on GDP growth (Rodrik, 2008; Bassey & Godwin, 2021). This makes REER potentially endogenous through simultaneity bias. In addition, terms of trade (TOT), defined as the ratio of export prices to import prices, may also be endogenously linked with economic growth. An improvement in TOT can raise national income and stimulate growth, but countries experiencing strong GDP growth may also experience a shift in the composition and pricing of their exports, thereby affecting TOT (Singh, 2023; Barro & Sala-i-Martin, 2004).

While external sector indicators like EXP, FDI, TO, REER, and TOT are important determinants of economic growth, their potential endogeneity must be carefully addressed in empirical analysis to ensure the validity of the results. To mitigate this, this study identified valid instruments for the System Generalised Method of Moments (System GMM), designed to produce consistent estimates in the presence of endogenous regressors (Arellano & Bover, 1995; Blundell & Bond, 1998). Hence, this study instrumented endogenous variables using lagged levels of endogenous variables as instruments for their first differences and vice versa. .

As set from the background of this study, it aimed to provide and expand an examination into the moderating impact of key trade-related variables on economic growth through interaction with export. Hence, an expanded form of Equation (6) is as specified below in Equation (7) with interaction terms:

The Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER), which reflects the relative price of domestic goods in foreign markets, adjusted for inflation and trading partner weights, is known to have a moderate effect on export and economic growth. When a country’s REER appreciates, its exports become less competitive, potentially weakening the export-growth linkage (Janus & Riera-Crichton, 2015; Rodrik, 2008). Conversely, a depreciated REER enhances competitiveness, reinforcing the positive contribution of exports to economic growth. Therefore, the interaction term between exports and REER helps us test whether the effectiveness of exports on GDP growth is conditional on the country’s exchange rate competitiveness. Freund and Pierola’s (2012) investigation of 92 episodes of sustained manufacturing export surges in developing countries revealed that these surges were often preceded by a substantial real exchange rate depreciation, making exports more competitive. This undervaluation spurred entry into new products and markets, collectively contributing over 40% of export growth during the surge. Similarly, FDI is known for bringing about spillover effects and scale efficiencies, amplifying exports (Bozsik et al., 2023; Sahoo & Dash, 2022; Rob & Vettas, 2003). Including an interaction between exports and FDI in the model allows us to evaluate whether the presence of FDI enhances export activities’ productivity and growth potential.

Rodrik (2008) found that undervalued exchange rates are significantly associated with faster growth, especially in developing countries with export-oriented strategies. Freund and Pierola (2012) also showed that large devaluations often precede sustained export surges and growth episodes.

While exports reflect external demand for domestically produced goods, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) often brings capital, technology, and management expertise, which can complement or substitute the benefits of exports. Including an interaction between exports and FDI in the model allows us to evaluate whether the presence of FDI enhances export activities’ productivity and growth potential (Borensztein et al., 1998; Alfaro, 2003). FDI may facilitate learning-by-doing, knowledge spillovers, and scale efficiencies that amplify export effects.

Borensztein et al. (1998) argue that the growth-enhancing effect of FDI depends on the absorptive capacity of the host country, particularly human capital and trade openness. Alfaro (2003) shows that FDI benefits are most significant when coupled with a strong financial system and export activity.

The study further proves the dynamic interactions between exports, foreign direct investment (FDI), and economic growth, panel Granger non-causality test developed by Dumitrescu and Hurlin (2012). This method is particularly suited for heterogeneous panels, as it tests the null hypothesis that there is no Granger causality for any individual unit in the panel, while allowing the alternative to hold for a subset of cross-sectional units.

4. Results and Discussion

The System Generalised Method of Moments (System GMM) results in Table 4 provides critical insights into the determinants of economic growth among East African Community (EAC) and Southern African Development Community (SADC) countries. These regions exhibit unique development challenges and opportunities shaped by their economic structures, integration efforts, and policy environments. The estimation confirms the dynamic nature of growth, with the lagged GDP growth coefficient (0.4364, p < 0.001) indicating that past growth strongly influences current performance. This persistence aligns with growth theory emphasising path dependence and cumulative development processes, as Barro (1991) and Islam (1995) noted. In dynamic economies like EAC and SADC, previous successes or setbacks shape investment climate, institutional quality, and human capital, collectively influencing subsequent growth phases.

Table 4.

Result system GMM.

Technological advancement emerges as a paramount growth driver, with a positive and highly significant coefficient (0.0157, p < 0.001). This finding resonates with endogenous growth theories that place technology at the centre of productivity improvements and innovation-led development (Romer, 1990; Grossman & Helpman, 1991). For EAC and SADC countries, where productivity gaps relative to developed economies remain substantial, technological progress is vital for economic transformation. Studies like Mlambo and Ntuli (2019) underscore the transformative impact of technological diffusion on industrial diversification and service sector expansion in Southern Africa. Regional initiatives such as the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) are also expected to enhance technology transfer by fostering larger integrated markets and encouraging foreign direct investment in knowledge-intensive sectors.

Exports also significantly and positively affect growth (0.23, p = 0.0055), corroborating the export-led growth hypothesis widely supported in the African economic literature (Allaro, 2012; Kollie, 2020; Akinlo & Okunlola, 2021). EAC and SADC countries are increasingly diversifying their export bases beyond raw commodities to manufactured goods and services, which generates higher value addition and employment. For example, Kenya’s burgeoning horticulture exports and South Africa’s automotive assembly sectors exemplify this transition (Ullah & Akhtar, 2018) The positive export-growth nexus emphasises the benefits of regional integration and trade facilitation in reducing barriers and enhancing competitiveness. However, constraints such as infrastructure deficits and regulatory bottlenecks must be fully addressed to capitalise on export opportunities (UNCTAD, 2020). The empirical evaluation of the export-led theory in Botswana by Sheridan (2014) and Bosupeng (2015) was supported by this conclusion. Based on Ee (2016), Sub-Saharan Africa shows evidence of export-led growth. This finding also supported the idea that rising exports encourage economic expansion. This finding disagrees with Lederman and Maloney’s (2007) assertion of a negative association between exports and growth.

Contrary to expectations, labour input is statistically insignificant in explaining growth (estimate = 0.0237, p = 0.91). While EAC and SADC countries boast young and expanding labour forces, quality and productivity remain challenging. This result aligns with Kuznets (1966) observation that economic growth depends more on labour quality improvements than quantitative labour increases as economies develop. Underemployment and skill mismatches in these regions further dampen labour’s growth contribution (AfDB, 2021). Policymakers must, therefore, invest in education, vocational training, and labour market reforms to enhance human capital and employability.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) also shows no statistically significant effect (estimate = 0.0545, p = 0.83). The growth benefits remain uneven despite attracting substantial FDI inflows, particularly in mining, telecommunications, and manufacturing. The literature stresses that FDI’s positive impact depends on domestic absorptive capacity, institutional quality, and linkages with local firms (Asiedu, 2002). In many EAC and SADC countries, weak governance, regulatory uncertainty, and inadequate infrastructure limit the transformative potential of FDI (UNCTAD, 2020). The insignificance found in the study signals the need for complementary reforms to ensure that foreign investments translate into productivity gains and broader economic development. The coefficient estimates for FDI are positive but insignificant. This indicated that during the research under consideration, FDI was not strong enough to cause an overall economic expansion, as reflected by an increase in the real GDP of all the economies. This result does not invalidate the economic hypothesis that foreign exchange earnings, such as FDI, increase investments and foster growth. Although net flows of foreign direct investment more than doubled from $14 billion in 2001 to $34 billion in 2008, it could not foster significant growth, although it shows signs of the appropriate way forward (Songwe & Winkler, 2012).

Trade openness displays a borderline significant negative coefficient (−0.1516, p = 0.05), challenging the conventional wisdom that openness unequivocally promotes growth (Sachs & Warner, 1995). This counterintuitive result may be explained by the vulnerability of EAC and SADC economies to external shocks, such as commodity price volatility and global demand fluctuations, which are often amplified by premature or poorly managed liberalisation (Rodrik, 1999; Ndulu et al., 2007). Furthermore, institutional weaknesses and infrastructural bottlenecks may prevent these countries from fully benefiting from trade integration. This finding underscores that trade liberalisation policies should be paired with robust domestic policies to manage adjustment costs and build competitiveness. The coefficient of trade openness in our study was negative and significant for the real GDP of the economies under consideration. The coefficient revealed that the expansion of trade openness contracted the economies of these countries. The result defies expectations. This finding does not support the conclusions of Malefane and Odhiambo (2018) or Grossman and Helpman’s (1990) hypothesis that trade openness promotes economic growth. However, C. Moyo and Khobai (2018) reported that trade openness threatens growth in certain economies, such as southern African countries, which supports this outcome. Rodrik (2006) asserted that overfocusing on an export-led orientation could be counterproductive to long-term growth if human and physical infrastructure are lacking. This case aligns with our finding that trade openness hurts growth. Most African countries, including those under consideration, lack the requisite human capital development and state-of-the-art infrastructure to sustain an export-led orientation (Tinga, 2020). Finally, the term of the trade coefficient estimate is positive, which is unexpected. The outcome contradicts the hypothesis that a worsening term of trade reduces growth.

Terms of trade and the interaction between FDI and exports are statistically insignificant, suggesting that their short-term fluctuations or combined effects may be less directly impactful on growth or mediated through other channels not captured here.

Diagnostic tests reinforce model reliability. The Sargan test’s p-value of 0.23 validates the chosen instruments, indicating no over-identification problems, while the absence of second-order autocorrelation (p = 0.67) confirms estimator consistency (Roodman, 2009). The highly significant Wald test (p < 0.001) confirms the joint relevance of the regressors. The use of two-step System GMM with Windmeijer-corrected standard errors for efficiency improved overall validity, which can be seen with the Harsan J test. Although this is seen as the Sargan test. Croissant and Millo (2008) averred that, although labelled as the Sargan test in R, the outcome is, in a real sense, the Hansen J test due to the use of robust standard errors, which causes the Sargan test to behave like the Hansen J test.

In conclusion, this study emphasises technology and exports as central to growth in EAC and SADC, consistent with broader African development literature. The results advocate for policies promoting technological innovation, export diversification, and trade facilitation. The insignificant role of labour and FDI highlights the importance of improving human capital quality and institutional frameworks to harness investment benefits. The complex effect of trade openness suggests cautious sequencing of liberalisation alongside structural reforms. Overall, sustainable growth in these regions hinges on a multifaceted strategy addressing technological, trade, labour, and institutional dimensions.

Panel Granger Causality Test Results

The results in Table 5 reveal strong evidence of a bidirectional Granger causal relationship between exports and economic growth. Specifically, the test for the null hypothesis that exports do not Granger-cause GDP was rejected with a statistic of 3.2504 and a p-value of 0.0012, indicating that exports Granger-cause GDP in at least one country in the panel. Conversely, the hypothesis that GDP does not Granger-cause exports was also rejected, with a statistic of 2.0789 and a p-value of 0.0376. These findings suggest a mutually reinforcing relationship between exports and economic growth, consistent with the Export-Led Growth Hypothesis (ELGH) and the feedback growth hypothesis (Yang & Wu, 2015; Ali & Li, 2018).

Table 5.

Causality Test.

In contrast, the FDI tests yielded no statistically significant causality in either direction. The null hypothesis that FDI does not Granger-cause GDP could not be rejected ( = −0.5716, p = 0.5676), nor could the reverse hypothesis that GDP does not Granger-cause FDI ( = 1.3360, p = 0.1815). Similarly, the null hypotheses of no causality between FDI and exports also held, as the p-values for both directions (FDI ⇒ exports: p = 0.8869; exports ⇒ FDI: p = 0.2905) were above conventional significance thresholds.

Taken together, the results suggest that exports play a significant dynamic role in driving GDP, and vice versa, within the sampled countries. However, FDI does not appear to exhibit any short-run causal link with either GDP or exports in this panel dataset. This may imply that the influence of FDI on growth and trade performance is either indirect, long-term, or conditional on other structural or institutional factors not captured in the current model specification.

These findings reinforce the importance of strengthening export capacity and diversifying export markets as a growth-enhancing strategy while encouraging further investigation into the complex channels through which FDI contributes to economic performance.

5. Conclusions

This study empirically reaffirms the relevance of the Export-Led Growth Hypothesis (ELGH) across EAC and SADC. By employing a dynamic panel technique and incorporating trade-related variables, the research confirms that exports and technological advancement are key drivers of economic growth across EAC and SADC economies. However, the insignificant role of labour and FDI, alongside the adverse effect of trade openness, underscores the limitations of relying on exports alone without addressing underlying structural weaknesses.

The bidirectional causality between exports and GDP suggests a reinforcing cycle, where growth fuels export capacity, and exports stimulate economic expansion. This shows a growth-led export scenario. However, the full benefits of this relationship are only achievable under conditions of strong institutional capacity, export diversification, and innovation.

Therefore, policy strategies must go beyond promoting exports to include investments in human capital, infrastructure, and institutional reforms. Moreover, trade openness should be strategically sequenced with safeguards that protect vulnerable sectors while promoting competitiveness. As Africa deepens its regional integration through the AfCFTA, this study contributes a timely call for recalibrated export-led strategies grounded in structural transformation, innovation, and inclusive growth. The policy part would invest heavily in infrastructure and human capital development for policy sustainability. Finally, there is a dire need for these countries to become more sophisticated in their exports since there is no long-term growth guarantee for the less sophisticated export base (Hausmann et al., 2006).

6. Limitations of the Study

A key limitation of this study is that the analysis focuses primarily on goods and service exports and does not disaggregate between commodity-based and manufactured exports. Moreover, despite using a dynamic model, structural breaks caused by political instability, pandemics, or global economic shocks (e.g., COVID-19 or the 2008 financial crisis) are not explicitly modelled, which could affect the interpretation of long-run relationships.

Lastly, the study does not incorporate institutional quality or governance indicators directly into the model, although these factors are known to mediate the impact of trade and FDI on growth. Further research could address these gaps by focusing individual country case studies, incorporating sectoral trade flows, and integrating institutional and political economy variables into the empirical framework. Methodologically, structural breaks caused by global shocks or instability could be considered.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.J.A. and O.O.O.; methodology, O.O.O.; software, O.O.O.; validation, O.J.A., O.O.O. and S.M.; formal analysis, O.O.O.; investigation, O.J.A. and O.O.O.; resources, S.M.; data curation, S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, O.O.O.; writing—review and editing, O.J.A. and S.M.; visualization, O.O.O.; supervision, O.J.A.; project administration, S.M.; funding acquisition, O.J.A. and S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not require ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study were obtained from the World Development Indicators (WDI) database maintained by the World Bank. The WDI data are publicly available and can be accessed through the World Bank’s official data portal at https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 24 June 2024). No special permissions were required to access or use the data.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Ojo Johnson Adelakun has not received any research grants or funding from any source, including the Economics Department at the School of Accounting, Economics & Finance, CLMS, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Westville Campus, Durban, South Africa, or the Department of Economics at the Faculty of Social Sciences, National University of Lesotho, Roma, Lesotho. Author Oluwafemi Opeyemi Ojo has not received any speaker honorarium from AdelakunOJ ECOMOD Laboratory, Ikeja, Lagos, Nigeria, and does not hold any stocks in the Export Department of Dangote Cement Plc, Leadway Marble House, Lagos 106104, Nigeria. Author Sakhile Mpungose has not received any research grants from the Economics Department at the School of Accounting, Economics & Finance, CLMS, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Westville Campus, Durban, South Africa.

Note

| 1 | All variables are in natural logarithms and expressed in first differences. The model was estimated using the System GMM estimator with two-step robust standard errors. |

References

- AfDB. (2021). African economic outlook 2021 (pp. 387–395). African Development Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghion, P., Bergeaud, A., Lequien, M., & Melitz, M. (2019). The impact of exports on innovation: Theory and evidence. Review of Economic Studies, 86(2), 1176–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajakaiye, O., & Ncube, M. (2010). Infrastructure and economic development in Africa: An overview. Journal of African Economies, 19(Suppl. 1), i3–i12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajide, K. B., & Raheem, I. D. (2016). Institutions-FDI nexus in ECOWAS countries. Journal of African Business, 17(3), 319–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinlo, T., & Okunlola, C. O. (2021). Trade openness, institutions and economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Jurnal Perspektif Pembiayaan Dan Pembangunan Daerah, 8(6), 541–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, L. (2003). Foreign direct investment and growth: Does the sector matter? In Harvard business school working paper (No. 01-083). Harvard Business School. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, G., & Li, Z. (2018). Exports-led growth or growth-led exports in the case of China and Pakistan: An empirical investigation from the ARDL and Granger causality approach. The International Trade Journal, 32(3), 293–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaro, H. B. (2012). The effect of export-led growth strategy on the Ethiopian economy. American Journal of Economics, 2(3), 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, M. (2003). Staple theory and export-led growth: Constructing differential growth. Australian Economic History Review, 43(3), 230–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M., & Bover, O. (1995). Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. Journal of Econometrics, 68(1), 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiedu, E. (2002). On the determinants of foreign direct investment to developing countries: Is Africa different? World Development, 30(1), 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awokuse, T. (2008). Trade openness and economic growth: Is growth export-led or import-led? Applied Economics, 40, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakari, S., & Tiba, S. (2020). The impact of internet on economic growth in North Africa: New empirical and policy analysis. Journal of Applied Economic Sciences, 15(3), 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balassa, B. (1985). Exports, policy choices, and economic growth in developing countries after the 1973 oil shock. Journal of Development Economics, 4(1), 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, R. J. (1991). Economic growth in a cross section of countries. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(2), 407–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, R. J., & Sala-i-Martin, X. (2004). Economic growth (2nd ed.). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bassey, G. E., & Godwin, B. I. (2021). Real effective exchange rate, international competitiveness and macroeconomic stability in Nigeria. International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management, 9(12), 195–217. Available online: http://ijecm.co.uk/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Bhandari, P. (2020, July 9). Descriptive statistics|definitions, types, examples. Scribbr. Available online: https://www.scribbr.com/statistics/descriptive-statistics/ (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Biyase, M., & Bonga-Bonga, L. (2014). Is the export-led growth hypothesis valid for African countries? An empirical investigation. Problems and Perspectives in Management, 12(2), 1–9. Available online: https://www.businessperspectives.org/images/pdf/applications/publishing/templates/article/assets/5863/PMF_2014_02_Biyase.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Blomström, M., & Hettne, B. (1984). Development theory in transition: The dependency debate and beyond—Third world responses. Zed. [Google Scholar]

- Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borensztein, E., De Gregorio, J., & Lee, J.-W. (1998). How does foreign direct investment affect economic growth? Journal of International Economics, 45(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosupeng, M. (2015). Exports and economic growth in Botswana: A causality analysis. Botswana Journal of Economics, 13(1), 45–60. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/77917/ (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- Bozsik, N., Ngo, D. M., & Vasa, L. (2023). The effects of foreign direct investment on the performance of small-medium enterprises: The case of Vietnam. Journal of International Studies, 16(1), 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, C., & Tovar-García, E. D. (2021). Trade and growth in developing countries: The role of export composition, import composition and export diversification. Economic Change and Restructuring, 54, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherif, R., & Hasanov, F. (2024). The pitfalls of protectionism: Import substitution vs. export-oriented industrial policy. Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade, 24(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chihaka, S. (2017, ). Regional integration: Addressing levels of intraregional trade in East and Southern Africa. World Customs Organization East & Southern Africa Regional Office for Capacity Building, 2nd Regional Research Conference, Harare, Zimbabwe. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, A., & Mavrotas, G. (2006). FDI and growth: What causes what? The World Economy, 29(1), 9–19. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/a/bla/worlde/v29y2006i1p9-19.html (accessed on 3 April 2024). [CrossRef]

- Clark, T. S., & Linzer, D. A. (2015). Should I use fixed or random effects? Political Science Research and Methods, 3, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croissant, Y., & Millo, G. (2008). Panel data econometrics in R: The plm package. Journal of Statistical Software, 27(2), 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuaresma, J. C., & Wörz, J. (2005). On export composition and growth. Review of World Economics/Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 141(1), 33–49. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40441033 (accessed on 2 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Deraniyagala, S., & Fine, B. (2001). New Trade Theory Versus Old Trade Policy: A Continuing Enigma. Camnbridge Journal of Economics, 25, 809–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, E. I., & Hurlin, C. (2012). Testing for Granger non-causality in heterogeneous panels. Economic Modelling, 29(4), 1450–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ee, C. Y. (2016). Export-led growth hypothesis: Empirical evidence from selected Sub-Saharan African countries. Procedia Economics and Finance, 35, 232–240. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212567116000290 (accessed on 2 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ego. (2024). Lessons from the Asian tiger economies for developing nations. MoneyRise. Available online: https://risevest.com/blog/asian-tiger-economies-lessons-for-nigerias-economy (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Farahane, M., & Heshmati, A. (2020). Trade and economic growth: Theories and evidence from the Southern African development community (IZA Institute of Labour Economics Discussion Paper Series, IZA DP No. 13679, pp. 2–24). IZA. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, N., Narain, J., & Ooft, G. (2020). Testing the export-led growth hypothesis: The case of Suriname. Social and Economic Studies, 69(1/2), 113–137. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/45387244 (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Freund, C., & Pierola, M. D. (2012). Export surges. Journal of Development Economics, 97(2), 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geda, A. (2005). Export development strategy, export success stories and lessons for Africa. The Challenge for Afreximbank. [Google Scholar]

- Gençtürk, F., & Kotabe, M. (2011). The effect of export assistance program usage on export performance: A contingency explanation. In The future of global business (pp. 459–485). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, J. A., & Williams, C. L. (2000). Export-led growth: A survey of the empirical literature and some noncausality results. Part 1 (Econometrics Working Paper No. 0001). Department of Economics, University of Victoria. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1990). Trade, innovation, and growth. The American Economic Review, 80(2), 86–91. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1991). Innovation and growth in the global economy. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann, R., Hwang, J., & Rodrik, D. (2006). What you export matters. Journal of Economic Growth, 12(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helpman, E., & Krugman, P. (1985). Market structure and foreign trade: Increasing returns, imperfect competition, and the international economy. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hordofa, D. F. (2023). Impacts of external factors on Ethiopia’s economic growth: Insights on foreign direct investment, remittances, exchange rates, and imports. Heliyon, 9(12), e22847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, N. (1995). Growth empirics: A panel data approach. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(4), 1127–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janus, T., & Riera-Crichton, D. (2015). Real exchange rate volatility, economic growth and the euro. The Journal of Economic Integration, 30(1), 148–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordaan, A., & Eita, J. H. (2007). Testing the export-led growth hypothesis for Botswana: A causality analysis (Working Papers). The University of Pretoria, Department of Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, W. S., & Marshall, P. J. (1985). Exports, causality, and growth in developing countries. Journal of Development Economics, 18, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollie, G. B. (2020). Export-led growth hypothesis in ECOWAS: A panel data analysis. African Journal of Economic Review, 8(2), 258–275. Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/304725/ (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Kripfganz, S., & Schwarz, C. (2019). Estimation of linear dynamic panel data models with time-invariant regressors. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 34(4), 526–546. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecbwp1838.en.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Kuznets, S. (1966). Modern economic growth. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lederman, D., & Maloney, W. F. (2007). Trade structure and growth. In Natural resources: Neither curse nor destiny (pp. 15–39). World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. W., & Vu, T. H. (2020). Global integration and productivity: Evidence from ASEAN economies. World Development, 129, 104884. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, R. E. (1988). On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22(1), 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malefane, M. R., & Odhiambo, N. M. (2018). Impact of trade openness on economic growth: Empirical evidence from South Africa. International Economics, 71(4), 387–416. [Google Scholar]

- Mankiw, N. G., Romer, D., & Weil, D. N. (1992). A contribution to the empirics of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(2), 407–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Smith, E. J. (2001). Is the export-led growth hypothesis valid for developing countries? A case study of Costa Rica. In Policy issues in international trade and commodities study series (No. 7). United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Mengistae, T., & Pattillo, C. (2004). Export orientation and productivity in sub-Saharan Africa. IMF Staff Papers, 51(2), 327–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlambo, C., & Ntuli, N. (2019). Technological innovation in Southern Africa: Regional and firm-level perspectives. Technovation, 81, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Moritz, L. (1997). Trade and industrial policies in the new South Africa (Research Report No. 97). Nordic Africa Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Moyo, B. (2023). Impact of SADC Free Trade Area on Southern Africa’s intra-trade performance: Implications for the African Continental Free Trade Area. Foreign Trade Review, 59(1), 146–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, C., & Khobai, H. (2018). Trade openness and economic growth in SADC countries. MPRA Paper, No. 84254. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/84254/ (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Mushi, H., & Ahmed, M. (2025). Analyzing the drivers of foreign direct investment inflows and their impact on economic growth in Tanzania. New Challenges in Accounting and Finance, 13, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndulu, B., O’Connell, S. A., Bates, R. H., Collier, P., & Soludo, C. C. (2007). The political economy of economic growth in Africa, 1960–2000. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Odhiambo, N. M. (2022). Is export-led growth hypothesis still valid for sub-Saharan African countries? New evidence from panel data analysis. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 31(1), 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangasamy, L. (2009). Exports and economic growth: The case of South Africa. Journal of International Development, 21(5), 603–614. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/jid.1501 (accessed on 24 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, F., & Silva, E. G. (2017). Export variety, technological content and economic performance: The case of Portugal. Industrial and Corporate Change, 26(3), 443–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehner, J., Baeza-González, S., & Barton, J. (2014). Chile’s resource-based export boom and its outcomes: Regional specialization, export stability and economic growth. Geoforum, 56, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rob, R., & Vettas, N. (2003). Foreign direct investment and exports with growing demand. SSRN Electronic Journal, 70(3), 629–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrik, D. (1999). Where did all the growth go? External shocks, social conflict, and growth collapses. Journal of Economic Growth, 4(4), 385–412. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40216016 (accessed on 25 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- Rodrik, D. (2006, August). Industrial development: Stylized facts and policies [Unpublished manuscript]. Harvard University, John F. Kennedy School of Government. Available online: http://www.ksg.harvard.edu/rodrik/ (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Rodrik, D. (2008). The real exchange rate and economic growth. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2008(2), 365–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, P. M. (1990). Endogenous technological change. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5), S71–S102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodman, D. (2009). How to do xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. The Stata Journal, 9(1), 86–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J. D., & Warner, A. (1995). Economic reform and the process of global integration. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 26(1), 1–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P., & Dash, R. K. (2022). Does FDI have differential impacts on exports? Evidence from developing countries. International Economics, 172, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, R. D. (2004). Stature decline and recovery in a food-rich export economy: Argentina 1900–1934. Explorations in Economic History, 41(3), 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samargandi, N., Fidrmuc, J., & Ghosh, S. (2020). Is the growth effect of financial development conditional on financial structure? Evidence from middle-income countries. Economic Modelling, 86, 196–216. [Google Scholar]

- Sanni, G. K., Musa, A. U., & Sani, Z. (2019). Current account balance and economic growth in Nigeria: An empirical investigation. Central Bank of Nigeria Economic and Financial Review, 57(2), 83–105. [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Paulino, A. U. (2000). Trade liberalization and export performance in selected developing countries. In Studies in economics (No. 0012). Department of Economics, University of Kent. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, J., & Sun, F. (1998). On the export-led growth hypothesis: The econometric evidence from China. Applied Economics, 30(8), 1055–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A., & Panagiotidis, T. (2004). An analysis of exports and growth in India: Cointegration and causality evidence (1971–2001). Review of Development Economics, 8(3), 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, B. J. (2014). Manufacturing exports and growth: When is a developing country ready to transition from primary exports to manufacturing exports? World Development, 64, 100–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, N. S., & Manap, T. A. A. (2005). Export-led growth hypothesis: Further econometric evidence from South Asia. The Developing Economies, 43(4), 472–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T. (2023). Do terms of trade affect economic growth? Robust evidence from India. Economics of Transition and Institutional Change, 31(2), 491–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songwe, V., & Winkler, D. (2012). Exports and export diversification in sub-Saharan Africa. World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Stephen, A., & Obah Daddy, O. (2017). The impact of international trade on economic growth in Nigeria: An econometric analysis. Asian Finance & Banking Review, 1, 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syarif, A. (2016). Export-led growth hypothesis: Comparison between Islamic and non-Islamic countries in ASEAN. Global Review of Islamic Economics and Business, 3(1), 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, A., & Abiy, S. (2022). Export performance and economic growth in Ethiopia: Evidence from VECM model. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 13(6), 78–91. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H., Huang, Y., Lin, C., & Liu, S. (2023). Trade networks and firm value: Evidence from the U.S.-China trade war. Journal of International Economics, 145, 103811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinga, C. L. (2020). Gender inequality and economic growth in developing countries. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/429684939.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Todaro, M. P., & Smith, S. C. (2014). Economic development (12th ed.). Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, W. G. (1981). Growth and export expansion in developing countries. Journal of Development Economics, 9, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]