1. Introduction

The government debt of most countries around the world has been increasing over the years. Most developed countries had the highest debt-to-GDP ratio during and after COVID-19. The countries with the highest amount of debt are countries found in Europe. It is evident that, in 2020, all countries had the highest debt-to-GDP ratio. Croatia had 687.99% in 2018, increasing to 633.16% in 2021 (

World Bank, 2023). This is followed by Greece with 237.12% in 2018, increasing to 208.81% in 2021, and Japan with 198.02% in 2018, increasing to 217.61% in 2021 (

World Bank, 2023). The second set of countries with the highest debt is North America, followed by Asia. Most African countries have the lowest debt compared to other countries worldwide (

World Bank, 2023).

Over the years, South Africa has been continually accumulating government/public debt. According to the Reserve Bank of South Africa, total public debt has sharply risen to 68.9% of the GDP in 2020, 68.7% in 2021, 70.2% in 2022, and 73.4% in 2023 (

South African Reserve Bank, 2024). This has raised some concern among different economic role-players about the future of South Africa’s debt path. High levels of public debt, if allowed to grow beyond the country’s productive capacity, would likely work against the growth and development of the economy (

Dabrowski, 2014). The COVID-19 pandemic appeared to have made it worse as the government had to continuously adjust its budget upwards, resulting in fiscal imbalances and debt sustainability becoming a matter of concern.

Saungweme and Odhiambo (

2020) mentioned that aggregate public debt negatively impacts growth.

Sovereign debt in South Africa arises primarily from the government’s budget deficit. In the past decades, debt levels have been continuously increasing worldwide, worsening due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has caused many governments to have a deficit in their finances. South African debt is associated mainly with the budget deficit; the government cannot cover its planned expenditure, and therefore, the deficit arises. Increased budget commitment to different sectors requires the government to have enough revenue to ensure that there is no deficit in its budget (

Galodikwe & Mah, 2023).

South Africa has been struggling with high levels of gross debt. Even though this concern is reasonable and acceptable, it might be useful to decompose the total debt into its domestic and foreign components and discover some interesting patterns that may assist in macroeconomic policymaking. Total debt in South Africa consists of both domestic debt and foreign debt. Domestic debt is the money borrowed by the government from local banks, individuals, and companies through government securities sales such as treasury bonds and bills. Foreign debt is the money the government borrows from another country’s government or foreign private lenders.

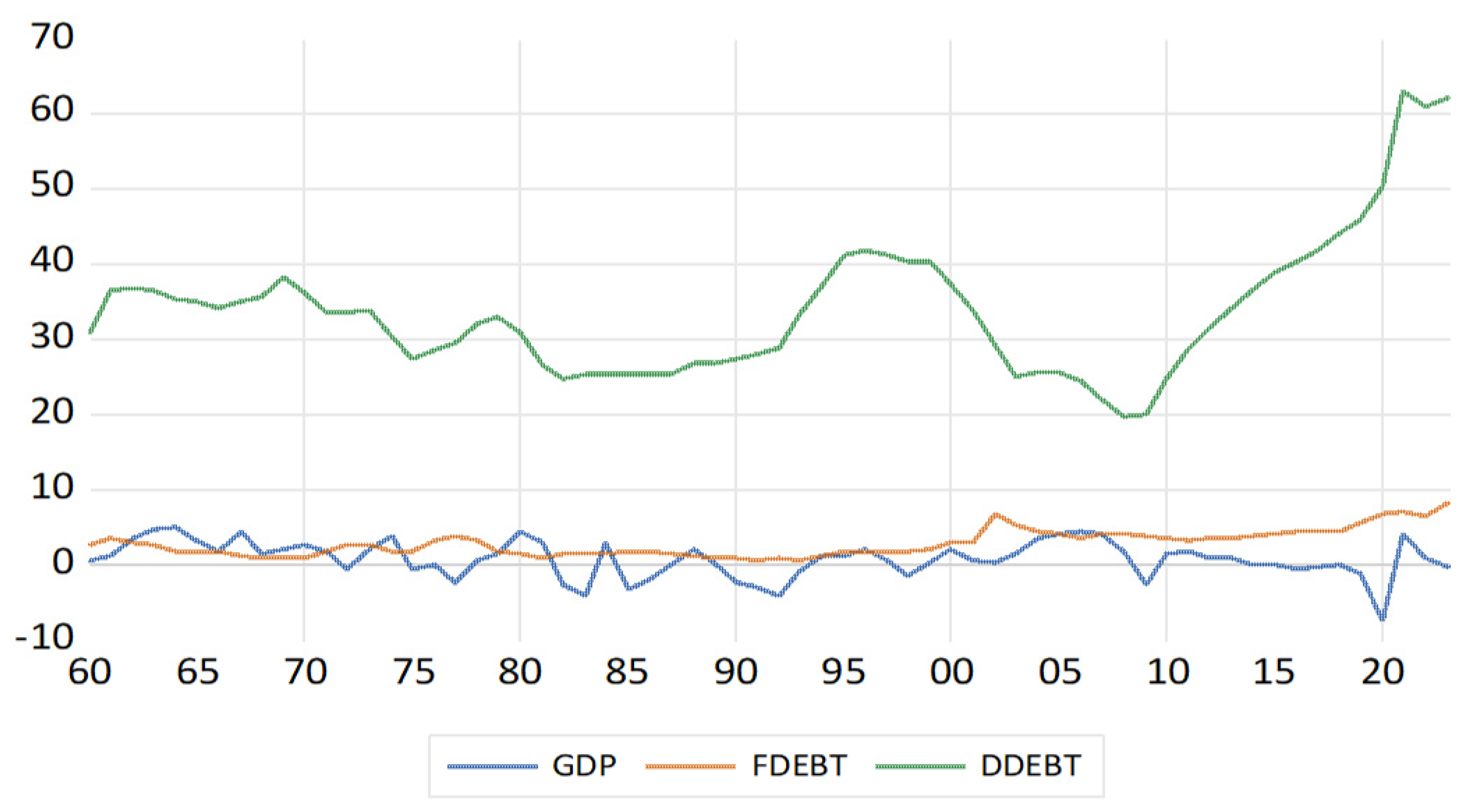

As shown in

Figure 1, according to the Reserve Bank of South Africa, the portion of domestic debt rose from 50.3% in 2019 to 65% in 2023, while foreign debt rose from 5.8% in 2019 to 8.3% in 2023 (

South African Reserve Bank, 2024). With an increase of 12.8% in total public debt from 2019 to 2020, it is interesting to note that while 11.5% was domestic, only 1.2% was foreign. However, when total debt decreased by 1% from 2020 to 2021, it was discovered that although domestic debt also decreased by the same 1%, the portion of foreign debt increased by 1%. Similarly, from 2021 to 2022, there was a 2.3% increase in total debt: 1.5% was domestic debt, while 0.8% was foreign debt. Most of the time, domestic debt is acquired mainly to finance the country’s primary deficits and ensure that appropriate monetary policies are implemented.

The relationship between foreign debt and economic growth has both positive and negative effects.

Zakaria (

2012) highlights that the productive use of borrowed funds is crucial for realising any potential economic benefits from debt, while

Ajuh and Oyeanu (

2021) mentioned that, in Nigeria, external debt often correlates negatively with growth outcomes.

Koyuncu and Demirhan (

2020) found that while external debt may positively impact growth under certain circumstances, its effects can quickly turn negative when thresholds of sustainability are breached.

Tchereni et al. (

2013) mentioned the detrimental effects of foreign debt, which are crowding out domestic investment, leading to increased vulnerability to external shocks. This can outweigh the potential benefits if the debt management is not robust.

Several studies support the assertion that domestic debt has a significant positive relationship with economic growth in Nigeria (

Didia & Ayokunle, 2020).

Akram (

2015) suggested that well-managed domestic debt can act as a catalyst for growth, provided it does not crowd out private investment. In Jordan, it has been shown that domestic borrowing effectively fosters economic expansion, albeit with consideration for its macroeconomic implications (

Fseifes & Warrad, 2020).

Saungweme and Odhiambo (

2020) argue that aggregate public debt negatively impacts growth, and the influence of domestic debt is significantly positive in the short run. Domestic debt may exert undue pressure on government revenues due to high interest burdens, potentially diminishing funding available for pro-growth sectors. Moreover, the relationship between domestic debt levels and economic growth often exhibits nonlinear characteristics, suggesting that there is an optimal level of domestic debt that supports growth, while exceeding this threshold could be detrimental (

Mbate, 2013).

Results from diverse geographical contexts reveal that while domestic debt can strengthen growth if managed prudently, foreign debt frequently carries risks that require careful handling. The overall consensus is that the potential benefits of both domestic and foreign debt significantly depend on how the funds are utilised and the strength of institutional frameworks that can mitigate risks associated with high debt levels while enhancing growth prospects (

Saungweme & Odhiambo, 2021b). Most studies focus on public debt as a whole, but few focus on the asymmetric effect of foreign and domestic debt in South Africa. This study will assess the positive and negative effects of foreign and domestic debt on growth in South Africa. The rest of this study is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews the theoretical and empirical literature;

Section 3 presents the econometric methods;

Section 4 provides the empirical results; lastly,

Section 5 outlines the conclusion of this study.

2. Literature Review

One theoretical approach that has received widespread attention within this context is the Keynesian perspective.

Keynes (

1937) emphasises the role of government intervention in stimulating economic growth and stability. In the Keynesian theory of public debt, governmental borrowing is perceived as a necessary tool for addressing the economic impulses of recession and reducing unemployment levels. As such, public debt is seen as a means by which the government can support economic recovery and mitigate potential negative impacts of economic contraction.

The main idea of the public debt overhang theory is that having too much debt can harm future economic growth. This theoretical concept posits that when a country’s debt goes up, it can cause less economic growth because the government has to use more of its money to pay off the debt. The theory suggests that this can create a self-reinforcing cycle, as lower economic growth means reduced resources to manage debt, further exacerbating the problem. In simple words,

Krugman (

1988) suggests that people who want to invest money would be more worried about banks having to pay a lot of taxes to cover the government’s debt than they would be about the costs of investing in something that will make money in the future. Debt overhang means having too much debt that it becomes burdensome and difficult to repay.

The relationship between foreign debt and economic growth has both positive and negative effects.

Saungweme and Odhiambo (

2021b) emphasise the importance of examining both domestic and foreign public debt separately, as their impacts on economic growth can differ significantly. Their findings suggest that while foreign debt can potentially stimulate growth under certain conditions, excessive reliance on it can lead to adverse outcomes, such as increased vulnerability to external shocks and higher debt servicing costs. Research conducted in Nigeria indicates that while foreign debt positively influences private investment, domestic debt has a negative impact in both the short- and long run (

Simon et al., 2023). This suggests that the effects of debt are not uniform and can vary significantly based on whether the debt is domestic or foreign. Similarly, studies in Egypt and Sri Lanka have shown that external debt can have both positive and negative effects on economic growth, depending on the economic context and the nature of the debt (

Sharaf, 2021;

Sumanaratne, 2022).

Olaoye et al. (

2022) indicate that excessive reliance on foreign borrowing can lead to vulnerabilities in the economy, including currency mismatches and increased susceptibility to external shocks. This phenomenon is mentioned within other contexts, where the presence of high levels of public debt can lead to reduced private sector investment due to increased competition for financial resources (

Matthew & Adetayo, 2022;

Lashari et al., 2017). The NARDL model provides a robust framework for understanding the complex interplay between domestic and foreign debt and their respective impacts on economic growth, inflation, and investment. The findings from various studies underscore the necessity for policymakers to carefully consider the composition of public debt and its implications for economic stability and growth. In Sri Lanka, the NARDL analysis demonstrated that both the stock of external debt and debt service payments significantly affect economic growth, underscoring the importance of managing foreign debt levels to ensure economic stability (

Sumanaratne, 2022). Furthermore, the crowding-out effect of public debt on domestic investment has been documented in various studies. In Sri Lanka, for instance, both domestic and foreign debt were found to crowd out domestic investment, which can hinder long-term economic growth (

Shiyalini & Suresh, 2022).

Baaziz et al. (

2015) found that public debt becomes detrimental to growth when it surpasses 31.37% of the GDP, highlighting the critical threshold that policymakers must consider. This is further supported by

Zhang et al. (

2022), who note that excessive public debt can lead to crowding out of private investment, thereby stifling growth prospects. The implications of these findings suggest that while some level of debt may be necessary for development, a delicate balance must be maintained to avoid negative repercussions. Additionally, the interaction between debt service obligations and economic growth has been a focal point of research.

Saungweme and Odhiambo (

2021a) argue that high debt service payments can constrain public investment, which is essential for economic growth.

Mhlaba and Phiri (

2019) assert that the long-run effects of public debt on growth are often negative due to the crowding out of productive investments. These studies collectively highlight the critical need for effective debt management strategies that prioritise growth-enhancing investments. Furthermore, the role of external factors, such as country risk and macroeconomic stability, cannot be overlooked.

Zakaria (

2012) highlights that the productive use of borrowed funds is crucial for realising any potential economic benefits from debt.

Musa et al. (

2023) found that in the presence of good governance, public debt promotes economic growth in the medium to higher quantiles.

Ajuh and Oyeanu (

2021) found that, in Nigeria, external debt often correlates negatively with growth outcomes.

Fseifes and Warrad (

2020) reported that external debt negatively impacts Jordan’s growth, which aligns with findings from Pakistan by

Shah et al. (

2016), where high debt servicing burdens curtailed investment and productivity.

Akram (

2015) mentioned that domestic debt can lead to the crowding out of private sector investment, thereby stunting economic growth.

Wulandari et al. (

2022) argue that foreign debt can enhance liquidity and provide much-needed capital for infrastructure projects, which is crucial for economic expansion in developing countries.

Junaedi et al. (

2022) found a correlation between foreign debt and Indonesia’s GDP and poverty levels, suggesting that well-managed foreign debt can stimulate economic activity and lead to poverty alleviation.

Changyong et al. (

2012) assert that foreign capital inflows can facilitate domestic investment and accelerate a country’s transition towards self-sustaining growth.

Koyuncu and Demirhan (

2020) found that while external debt may positively impact growth under certain circumstances, its effects can quickly turn negative when thresholds of sustainability are breached. The relationship between foreign debt and economic growth often follows a nonlinear pattern, with a threshold identified beyond which additional debt can restrict growth (

Changyong et al., 2012). Pattillo et al. noted a critical point around 35 to 40% of GDP at which foreign debt begins to inversely correlate with growth potential (

Changyong et al., 2012).

Omimakinde and Onifade (

2022) found that while domestic debt may yield positive short-term effects, its long-term implications can be negative unless directed towards growth-enhancing projects.

Didia and Ayokunle (

2020) suggest that domestic debt significantly contributes to economic growth in Nigeria over the long term, contrasting with the persistent negative effects associated with external debt. Several studies support the assertion that domestic debt has a significant positive relationship with economic growth in Nigeria (

Didia & Ayokunle, 2020). Well-managed domestic debt can act as a catalyst for growth, provided it does not crowd out private investment (

Akram, 2015).

Saungweme et al. (

2023) examined the symmetric and asymmetric impact of public debt on economic growth in Côte d’Ivoire using both linear and nonlinear autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) models. The nonlinear autoregressive distributed lag (NARDL) findings indicate that, on average, positive changes to public debt led to economic decline in the long run, while negative changes caused an economic upturn in the short run. The findings also show that GDP growth responds rapidly and strongly to negative changes in public debt.

Eric (

2024), on Nigeria’s government debt and its impact on GDP growth from the period 1991 to 2022, shows that the responsiveness of GDP growth is stronger for the negative than positive values of debt.

Aloulou et al. (

2023) examined the symmetric and asymmetric impact of external debt on economic growth in Tunisia between 1965 and 2019. The linear autoregressive distributed lag ARDL model was used, and the results show that economic growth is more sensitive and favourable to decreases than to increases in external debt, which, in turn, means that maintaining debt at relatively high levels is detrimental to Tunisian economic growth.

Sharaf (

2021) determined the asymmetric and dynamic effects of public debt on private investment in Nigeria from 1990 to 2019. According to the NARDL modelling technique, there was a significant instant positive impact on domestic and foreign debt shocks in the short run.

Sharaf (

2021) examined the asymmetric and threshold impact of external debt on economic growth in Egypt during the period 1980 to 2019. The paper uses an NARDL bounds testing approach. The results of the NARDL model show a robust, statistically significant negative long-run impact on economic growth stemming from both positive and negative external-debt-induced shocks. In terms of magnitude, on the one hand, the impact of external-debt-induced negative shocks exceeds that of the positive. In the short and long run, on the other hand, the growth impact of external debt in Egypt is symmetric.

Sharaf et al. (

2024), in the estimation of the NARDL model for Brazil, revealed that foreign debt does not have a statistically significant long-term impact on inflation, contrasting with findings from other countries where such relationships were more pronounced. This discrepancy highlights the importance of context when analysing the effects of debt, as different countries may exhibit unique responses to similar debt levels.

Mosikari and Eita (

2021) investigated the asymmetric relationship between government debt and GDP growth in Namibia. This study applied the NARDL methods to determine the asymmetrical effect of government debt on GDP growth. This shows that the responsiveness of GDP growth to positive values of debt is different to that of negative values of debt. The responsiveness of GDP growth to negative values of debt is greater than to positive values of debt. This implies that it is important for Namibia to have manageable debt and fiscal sustainability in order to increase its GDP growth.

The impact of foreign and domestic debt on South Africa’s economic growth is a complex and multifaceted issue that has garnered significant attention in recent academic studies. A notable research gap exists in understanding the nuanced effects of these two types of debt, particularly within the context of South Africa’s unique economic landscape.

3. Econometric Methods

The model below is used to determine the linear and nonlinear effects of debt on economic growth in South Africa. The model of

Redda (

2020) was modified to obtain the following equation:

where

is the gross domestic product,

is domestic debt as a percentage and

is total foreign debt as a percentage,

, are the coefficients, and

is the error term. Annual data from 1960 to 2023 was obtained from the South African Reserve Bank (

South African Reserve Bank, 2024) for the following variables: total domestic debt as a percentage, total foreign debt as a percentage, and gross domestic product.

The nonlinear autoregressive distributed lag (NARDL) technique is used.

Shin et al. (

2014) developed the NARDL model, where the independent variables are decomposed into positive and negative results. The NARDL method of analysis is used to avoid model misspecification errors, as the NARDL method considers the asymmetric relationship between the dependent and the independent variables (

Shin et al., 2014). The NARDL method accommodates variables of mixed integration orders I(0) and I(1) while Johansen cointegration approaches require that the variables be all I(1). The advantage of the NARDL method is its ability to detect asymmetric effects, which is crucial for understanding complex economic dynamics. It captures both short- and long-run asymmetries, differentiating the effects of positive and negative changes in independent variables, which other techniques, such as the Vector Error Correction Model and Engle–Granger, cannot (

Shrestha & Bhatta, 2018).

The estimation starts with descriptive statistics, correlation, and then the unit root test. The order of integration is determined, and the next step is the lag length selection criteria. After the appropriate lag is chosen, the NARDL bounds cointegration follows. The next step is the estimation of the long- and short-run nonlinearity of the debt variables. The diagnostic and stability tests then follow it.

To analyse multicollinearity, this study uses the correlation matrix method. While this approach is traditionally applied to detect multicollinearity among independent variables, it is also effective in evaluating the relationship between the dependent variable and the independent variables. Therefore, the correlation matrix not only identifies multicollinearity among predictors but also examines the complex interactions between the dependent variable and independent variables. Correlation is a method used to detect multicollinearity (

Gujarati & Porter, 2008). Multicollinearity occurs when a regression model includes multiple explanatory variables that show significant correlations with each other and with the dependent variable (

Young, 2018). A common guideline suggests that if the pairwise or zero-order correlation coefficient between two predictors exceeds 0.8, it indicates a potential multicollinearity problem (

Gujarati & Porter, 2008).

The augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) and Phillips and Perron (PP) unit root tests were used to test for stationarity. The ADF has heterogeneity in the distribution of the disturbance term, and the PP test was carried out to determine the confirmatory unit root results (

Asteriou & Hall, 2011). The Phillips–Perron tests (PP) correct the t-statistics of the coefficient in the autoregressive regression model (

Asteriou & Hall, 2011;

Phillips & Perron, 1988). It is performed at the intercept, intercept and trend, and none.

When the variables are stationary at level, it is integrated at I(0); if they are at the first difference, then they are integrated at I(1), and if they are at the second difference, then they are integrated at I(2) (

Asteriou & Hall, 2011). If the variables are stationary at I(0) and I(1), then the ARDL is best. The next step is the bounds cointegration.

The bounds test, developed by

Pesaran and Shin (

1995) and

Pesaran et al. (

1996), is ideal when dealing with one co-integrating vector. When employing the bounds test of cointegration and considering the null-hypothesis to come to a decision, the F-statistic of the test should be statistically significant to reject the null hypothesis of no long-run relationship or no cointegrating relationship, and therefore, the alternative hypothesis of a cointegrating relationship will be concluded. This study finds it very crucial to determine the presence of asymmetry in the relationship between domestic debt, foreign debt, and GDP. After the confirmation of the cointegration, this study estimated the long-run asymmetries.

The short-run dynamics are presented as shown below.

Diagnostic tests are used to confirm that the model is appropriately stated. For the normality test, the Jarque–Bera test is used since it is the most commonly used for large samples (

Brooks, 2014). For heteroscedasticity, the white heteroscedasticity test is performed to see whether the residuals and explanatory variables are related. Serial correlation is the relationship between several series of observations over time or place (

Gujarati & Porter, 2008). This is predicated on the idea that the disturbance term associated with any given observation is independent of the disturbance term associated with any other observation (

Gujarati & Porter, 2008).

For the stability test, the Ramsey reset test is used to determine whether the response variable can be described by the fitted values of nonlinear combinations of the study that was utilised in the model. The test is carried out to ensure that no misspecifications of any kind, i.e., ensuring stability, occur (

Brooks, 2014).

4. Empirical Results

The asymmetric results of foreign and domestic debt on South Africa’s economic growth are discussed below. It starts with a summary of statistics.

4.1. Summary Statistics of Variables

The average value of domestic debt is 33.3%, foreign debt is 2.7%, and the GDP is 0.71% in South Africa, as shown in

Table 1 below.

4.2. Correlation Matrix of Variables

According to

Shieh (

2010), multicollinearity is not a problem when dealing with dynamic models such as NARDL. However, we have to check the correlation among the variables of this. According to

Gujarati and Porter (

2008), a correlation coefficient that is greater than 0.8 indicates severe multicollinearity.

Table 2 shows low correlations among the variables in this study.

Table 2: Correlation matrix of variables.

4.3. Structural Break

Table 3 presents the analysis of structural breaks utilising dummy variables. This approach uncovers relationship alterations within the data over time by integrating dummy variables into the regression equation. These variables assist in identifying changes in intercepts or slopes, signalling structural modifications in the fundamental data-generating mechanism across various time frames.

4.4. Unit Roots

The unit root results reveal that GDP is stationary at level I(0), while FDEBT and DDEBT are stationary at the first difference, I(1), as shown in

Table 4 below.

4.5. NADRL Bounds Cointegration Results

Table 5 reveals the NARDL bounds cointegration results. The results reveal that there is cointegration among our variables since the F-statistic value is greater than the upper-bound values.

After determining cointegration, we proceed to estimate the long-run relationship.

4.6. Long-Run Relationship Results

The asymmetric cointegration long-run results are presented in

Table 6. It shows the statistical significance and the relationship of domestic debt and foreign debt with gross domestic product in symmetry for South Africa.

A positive change in foreign debt in the long run in South Africa has a positive and statistically significant effect on economic growth. Every 1-unit increase in foreign debt will lead to a 2.214443-unit increase in gross domestic product. This means that, in the long run, the increase in foreign debt leads to an increase in gross domestic product.

Sharaf (

2021) obtained the same results, which confirm our results. On the other hand, there is a negative change in foreign debt in South Africa, which causes gross domestic product to decrease, but the relationship is statistically insignificant. From these results, an increase in foreign debt will lead to an increase in gross domestic product in South Africa, which is contrary to the results of

Ajuh and Oyeanu (

2021) but in line with that of

Koyuncu and Demirhan (

2020), who found out that external debt may positively impact growth under certain circumstances.

The positive effect of foreign debt on economic growth in South Africa stems from its relatively lower cost, discipline-imposing nature, and its external financing benefits. Foreign borrowing usually comes with greater scrutiny from international lenders or capital markets. The need to adhere to repayment obligations and maintain credibility in global markets often imposes fiscal discipline and incentivises sound macroeconomic policy, thereby encouraging better debt management.

A positive change in domestic debt in South Africa has a negative and significant effect on gross domestic product in South Africa. Every 1-unit increase in domestic debt will lead to a 0.233567-unit decrease in the gross domestic product in South Africa. In other words, in the long run, an increase in domestic output leads to a decrease in gross domestic product in South Africa. On the other hand, a negative change in domestic debt has a positive and significant effect on gross domestic product. A 1-unit decrease in domestic debt will lead to a 0.686992-unit decrease in gross domestic product in South Africa. In other words, in the long run, the decrease in domestic debt leads to an decrease in gross domestic product in South Africa.

Omimakinde and Onifade (

2022) state that, in the long term, domestic debt has a negative relationship with growth, which is in line with our results.

Domestic debt is more likely to be expensive, inefficiently used, and fiscally destabilising, largely due to institutional weaknesses, poor fiscal discipline, and limited financial market depth. The negative effect of domestic debt on economic growth in South Africa’s gross domestic product could be due to the mismanagement of State-Owned Enterprises. Much of the domestic debt is absorbed by funding bailouts for inefficient public entities, such as Eskom and the South African Airlines. Domestic debt is often more prone to fiscal indiscipline, with low accountability and politicised allocation of resources. Also, South Africa’s domestic debt carries relatively higher interest rates, as the government borrows at premium rates due to risk perceptions, inflation expectations, and a narrow savings base. This raises the cost of servicing the debt and crowds out private investment. Lastly, rising domestic debt signals fiscal stress and a shrinking tax base, raising concerns about sustainability and deterring both foreign and domestic investment.

In the long run, in South Africa, an increase in foreign debt will cause the gross domestic product to increase. An increase in domestic debt in South Africa will cause gross domestic product to decrease, while a decrease in domestic debt will cause gross domestic product to increase in South Africa. This means that for the gross domestic product to increase, there is a need for an increase in foreign debt and total domestic debt in South Africa.

4.7. Short-Run Relationship Results

A negative and statistically insignificant relationship was found between foreign debt and GDP in South Africa. The asymmetric short-run results are presented in

Table 7 below.

In the short run, a positive change in foreign debt and lag-one of foreign debt are negative, but the positive change in foreign debt is significant, while lag-one of the positive changes in foreign debt is insignificant. Furthermore, in the short run, an increase in domestic debt has a positive and significant relationship with GDP. A decrease in domestic debt has a negative and statistically significant relationship with GDP.

Saungweme and Odhiambo (

2020) argue that aggregate public debt negatively impacts growth, and the influence of domestic debt is significantly positive in the short run. The positive changes to public debt led to economic decline in the long run, while negative changes caused an economic upturn in the short run and long run; on the other hand, the growth impact of external debt in Egypt is symmetric.

The error term is negative and statistically significant, with a speed value of −0.831359 for equilibrium to be established in this model. The probability value of the F-statistic is significant. Since his model is good, we proceed to check the evidence of asymmetric among our variables.

4.8. Parsimonious Asymmetric Test Results

The parsimonious asymmetric model on which the Wald test is performed to confirm the presence of asymmetric results is presented in

Table 8. This is the model that was discussed above; it has been rearranged to obtain the right identification to test for asymmetry.

4.9. Wald Test Results

The Wald test results were performed on the model in

Table 9 above, and the results presented in

Table 9 represent the asymmetric results for both the long and short run.

Table 9 shows that there is evidence of long-run asymmetry between domestic debt and GDP in both the long and short run in South Africa. In the short and long run, there exists an asymmetric relationship between growth and external debt, as mentioned by

Sharaf (

2021), which confirms our results of asymmetry.

4.10. Stability Test Results

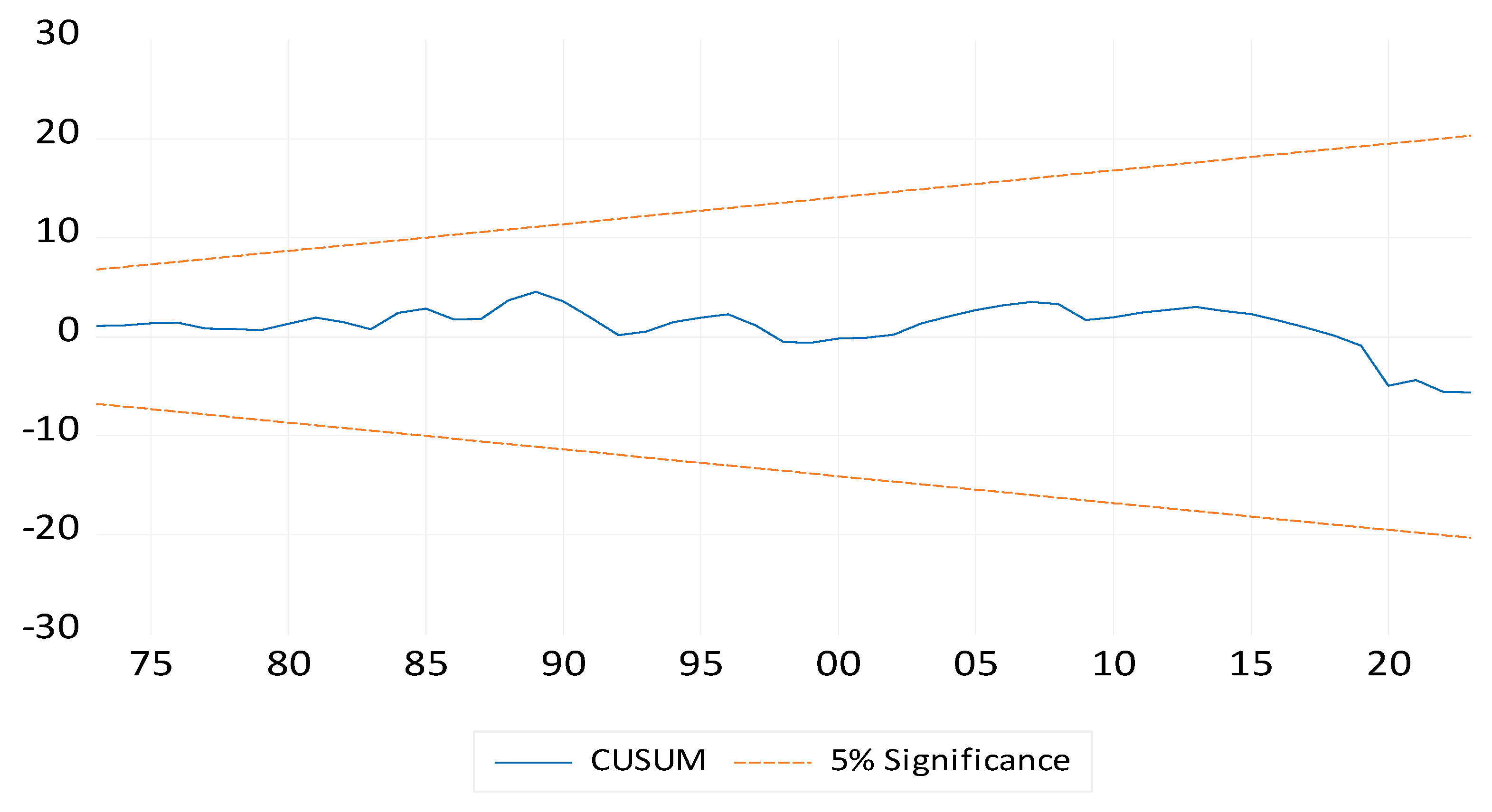

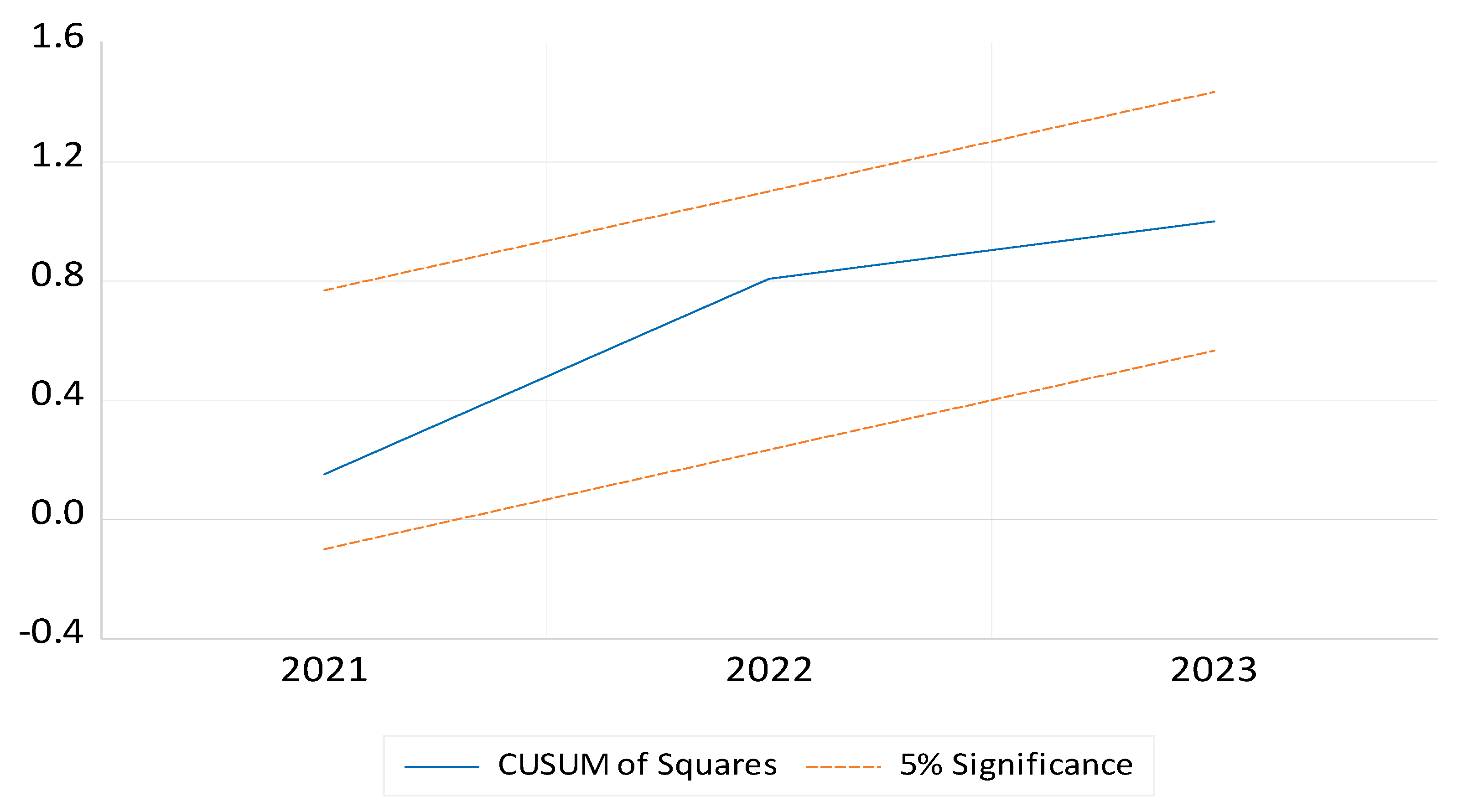

As shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, the estimated model is stable since the residuals are within the 5% significance interval.

4.11. Diagnostic Test Results

The stability test results are all good. They meet all classical linear assumptions as shown in

Table 10 below.

5. Conclusions

This research aims to assess the possible asymmetric effect of foreign and domestic debt on economic growth in South Africa using the NARDL method. The results reveal that a positive change in total domestic debt will cause an increase in gross domestic product in South Africa. A positive change in domestic debt will cause the gross domestic product to decline, while a negative change in domestic debt will cause the gross domestic product in South Africa.

In South Africa, a positive change in foreign debt will cause the gross domestic product to increase. South Africa’s post-COVID debt management strategy for foreign debt must reduce exchange rate vulnerability, limit reliance on costly commercial debt, strengthen institutional frameworks, and improve transparency and investor confidence. By integrating foreign debt policy into a coherent macroeconomic framework and leveraging concessional funding for strategic development objectives, South Africa can manage its foreign debt prudently while supporting inclusive and resilient economic recovery.

A positive change in domestic debt will cause the gross domestic product to decrease. The results exhibit that a positive change in domestic debt will lead to a decline in economic growth, whereas a negative change in domestic debt leads to an increase in gross domestic product in the long run.

Post-COVID-19, South Africa’s domestic debt management must be rooted in lengthening the maturity profile of debt, deepening domestic capital markets, containing debt-service costs, boosting growth through structural reforms, and ensuring debt remains aligned with broader fiscal and monetary policy goals. Maintaining a credible medium-term fiscal consolidation plan anchored by effective debt management will be essential for preserving South Africa’s macroeconomic stability and regaining policy flexibility.

Future research could benefit by considering other macroeconomic variables (e.g., exchange rate volatility and political risk) in the debt–growth relationship. This study further recommends that future studies in this area should use panel estimation techniques to examine the relationship between debt variables and economic growth at the provincial level. A key limitation of this study was the lack of quarterly data for all the variables of the study.