2.1. Endogenous Development

The interpretation known as endogenous development was developed in the early 1980s. Its main proponent was the Spaniard Antonio Vázquez-Barquero, accompanied by researchers, such as Sergio Boisier and Jair do Amaral Filho. This interpretation sees development as a territorial process in which society’s capacity for innovation is the mechanism that drives the transformation of the economy. It also considers that development policies are more effective when designed and implemented by local actors (

Vázquez-Barquero, 2010).

According to

Amaral Filho (

1996), the concept of endogenous development is associated with the rupture caused by the traditional theory of growth. This theory was based on a production function in which the volume of production (Y) was a function of two factors, namely capital (K) and labor (L). This traditional theory was represented mainly by R. Solow, and its break was observed due to the emergence of endogenous growth theories (represented mainly by R. Lucas and P. Romer).

Traditional theory explains output variation (dY) through marginal productivity coefficients of production factors, assuming linearity, homogeneity, and constant returns. In contrast, R. Lucas and P. Romer introduced endogenous factors—such as human capital, knowledge, information, and R&D—into the growth model, previously treated as exogenous (

Amaral Filho, 1996).

From the endogenous development perspective, growth must be rooted in the territory, relying on entrepreneurial capacity and investments based on local resources and savings. Without these, long-term development is limited (

Vázquez-Barquero, 2010).

Amaral Filho (

1996) defines endogenous development as a bottom-up process, driven by each region’s own socioeconomic potential, rather than by top-down state planning.

From the endogenous perspective, development is structured by the local actors rather than through centralized planning (

Amaral Filho, 1996). In terms of its theoretical construction, the endogenous development theory is an interpretation based on the contributions of classical and contemporary economists. In particular, it draws on the contributions of

Schumpeter (

1934) and

Kuznets (

1966) on capital formation, technological change, and productivity growth; those of

Marshall (

1890,

1919) and

Rosenstein-Rodan (

1943) on the organization of production and rising incomes; those of

Perroux (

1955) and

Hoover (

1948) on growth poles, urban development, and agglomeration economies; and those of

Coase (

1937) and

North (

1990) on the development of institutions and the reduction of transaction costs. From this perspective, endogenous development makes an effort to discuss sustained productivity growth within the framework of economic and social progress (

Vázquez-Barquero, 2007, p. 203).

In this sense, the foundations of endogenous development and its proposals demonstrate compatibility with other, more conventional approaches to development (

Vázquez-Barquero, 2007). Nevertheless, it is possible to state that the perspective of endogenous development is heterodox, understanding that economic growth must be understood as a process with deep historical roots and incorporating relevant aspects of the notion of growth that go beyond the limitations imposed by the neoclassical mainstream (

Conceição, 2002a).

Countries’ interest in the development of each of their territories, including endogenously, may have been motivated by the growing demand for decentralization, whether political or territorial, and by the recognition that the realization of each individual’s life project is highly dependent on the behavior of the environment in which they live (

Boisier, 1996).

Specifically, regarding the development of rural regions,

Vázquez-Barquero (

2010) suggests that there is a more significant problem considering the new international division of labor due to such factors as depopulation, lack of basic infrastructure, and environmental pollution. In this sense,

Vázquez-Barquero (

2010) points to the need for rural regions to specialize in productive activities to have competitive advantages in national and international markets.

Rural development can advance when institutions are flexible and there is strong capacity for innovation, entrepreneurship, and global integration through productive, commercial, and technological networks (

Vázquez-Barquero, 2010). In a context of globalization and increasing territorial competition, the endogenous development approach becomes a useful tool to understand regional dynamics and promote capital accumulation (

Vázquez-Barquero, 2000).

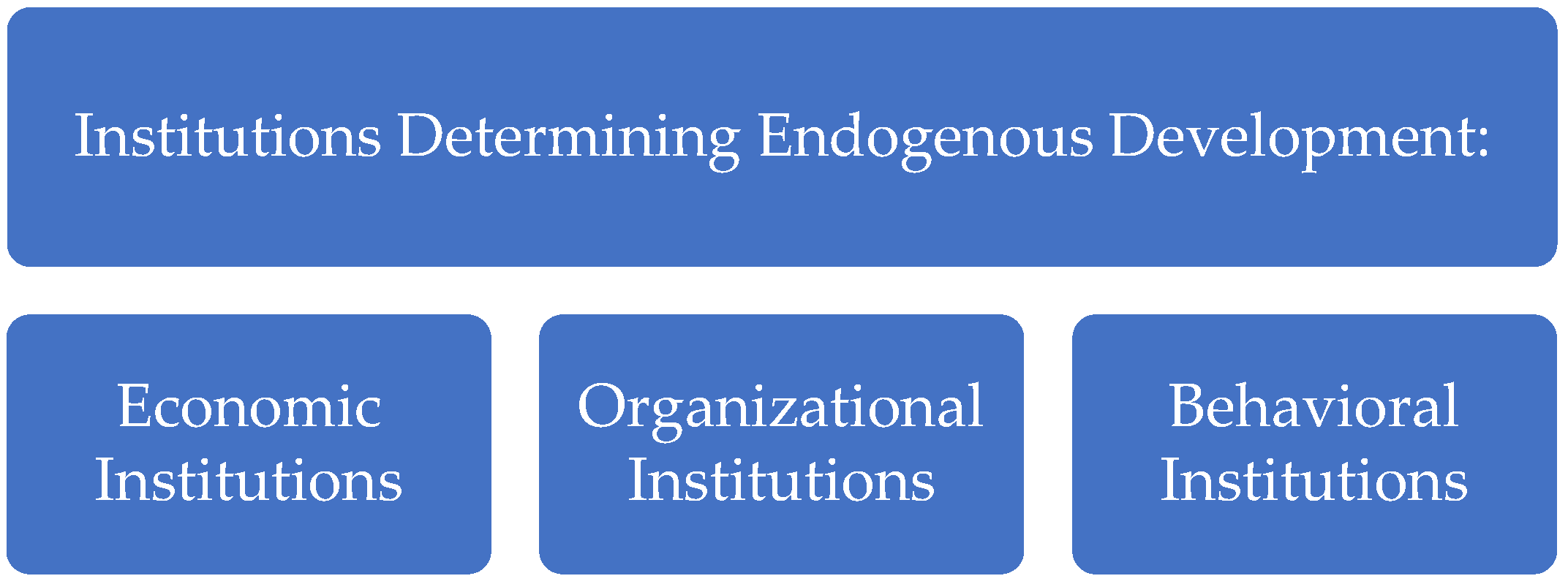

The processes of capital accumulation and the consequent development of economies depend, according to

Vázquez-Barquero (

2000,

2003,

2007), on a set of determining factors that act synergistically, which can be defined as (i) the diffusion of innovations, (ii) the flexible organization of production, (iii) territorial and urban dynamics, and (iv) the density (and flexibility) of the institutional matrix.

Vázquez-Barquero (

2003) argues that cities and regions grow more effectively when the following four factors converge: innovation diffusion, flexible production, urban development, and institutional evolution. Together, these elements enhance productivity and returns by fostering economies of scale, external economies, and lower transaction costs.

2.2. Factors Determining Endogenous Development

The first determining factor of endogenous development to be analyzed is the diffusion of innovations and knowledge. The endogenous development theory maintains that capital accumulation is ultimately the accumulation of knowledge and technology. In this sense, economic development depends on introducing and diffusing innovations and knowledge, which promote the transformation and renewal of production systems (

Vázquez-Barquero, 2000).

Economies of scale are generated for the benefit of all system members to the extent that the introduction and diffusion of innovation and knowledge improve the stock of technological knowledge in a given production system. Thus, innovation can be understood as the collective result of cooperation between the companies that make up the system, promoting greater productivity and increasing the competitiveness of local economies (

Vázquez-Barquero, 2003).

Schumpeter (

1997) highlights entrepreneurship and innovation as the driving forces of economic development. For him, development results from “new combinations”, which include (1) introducing a new good or a new quality of an existing good; (2) applying a new production method, even if not based on scientific discovery; (3) opening a new market, whether or not it previously existed; (4) accessing a new source of raw or semi-processed materials; and (5) establishing a new industrial organization, such as forming or breaking up monopolies (

Schumpeter, 1997, p. 76).

In other words, innovation can occur in various ways, whether through designing a new product to be marketed, a new manufacturing method, or even opening up a new market. According to

Vázquez-Barquero (

2003), when firms in a given production system have a low capacity for learning, there will be resistance to the diffusion of innovations, as well as when a lack of flexibility makes it difficult to adopt innovations.

In highlighting the importance of innovation and the diffusion of knowledge for the performance of economies, Vázquez-Barquero states that:

Economic growth can persist if investments in capital goods, human capital, and R&D generate increasing returns through the diffusion of innovation and knowledge. Training, technology adoption, and R&D investment create spillover effects, spreading innovation across the production system. Knowledge transfers through formal and informal networks, customer-supplier interactions, and the labor market. Even less innovative firms benefit, as they gain access to knowledge without raising production costs. As a result, the entire economy benefits from the increasing returns produced by individual firms’ investments (

Vázquez-Barquero, 2010, p. 39).

Furthermore, it is understood that the introduction and diffusion of innovations are conditioned by the characteristics of the institutions (social, cultural, and political norms and rules, and research centers, universities, and associations) of a given production system and its creative capacity. In other words, the more flexible and the higher the quality of the actors’ networks, the more effective the innovation mechanisms will be (

Vázquez-Barquero, 2003).

Regarding urban development,

Vázquez-Barquero (

2003) emphasizes the role of cities as hubs for learning, innovation, and technology diffusion. The concentration of people, firms, and organizations promotes interaction and knowledge exchange, fostering continuous learning. Urban agglomerations offer the scale needed for innovation, while physical proximity and worker mobility enhance communication and the spread of ideas (

Vázquez-Barquero, 2003).

Furthermore, cities have great potential for generating development, and cities have been pushed to create local strategies to respond to the competitiveness resulting from globalization processes, stimulating endogenous development processes (

Vázquez-Barquero, 2003).

Urban centers have become the preferred spaces for development because they are in cities where industrial plants and service offices are located and investment decisions are made (

Vázquez-Barquero, 2010;

Lasuen, 1973). Cities also have diversified production systems that stimulate economic dynamics, spaces that encourage networking and the diffusion of innovations, and externalities that generate growing incomes (

Vázquez-Barquero, 2010).

According to

Vázquez-Barquero (

2010), economies develop when firms conduct their activities in dynamic cities and urban regions, providing firms with quality resources and enabling externalities and economies of proximity that favor firm efficiency.

In addition to innovation diffusion and urban development,

Vázquez-Barquero (

2000) highlights the flexible organization of production as key to endogenous development. The structure of relationships between firms, suppliers, and customers shapes local productivity and competitiveness. Thus, organizing local production systems becomes a central element in capital accumulation.

The formation and development of networks and flexible systems of companies, as well as the interaction of companies with local players and strategic alliances, can generate economies (external and internal) of scale in local production systems. In addition, economies of scale are also observed in product research and development, thus reducing transaction costs between companies (

Vázquez-Barquero, 2007).

Amaral Filho (

2002) also emphasizes the role of flexible production structures in regional development. Regardless of the label—industrial district, cluster, innovative environment, or local productive system—these arrangements share key elements, including social capital, collective strategies for production and market access, and political–institutional coordination.

In this sense, the interaction between the agents of the production systems takes center stage. In other words, “it is no longer a question of a passive agglomeration of companies, but of an active collective of public and private agents acting in the same interest: that of maintaining the dynamics and sustainability of the local production system” (

Amaral Filho, 2001, pp. 277–278).

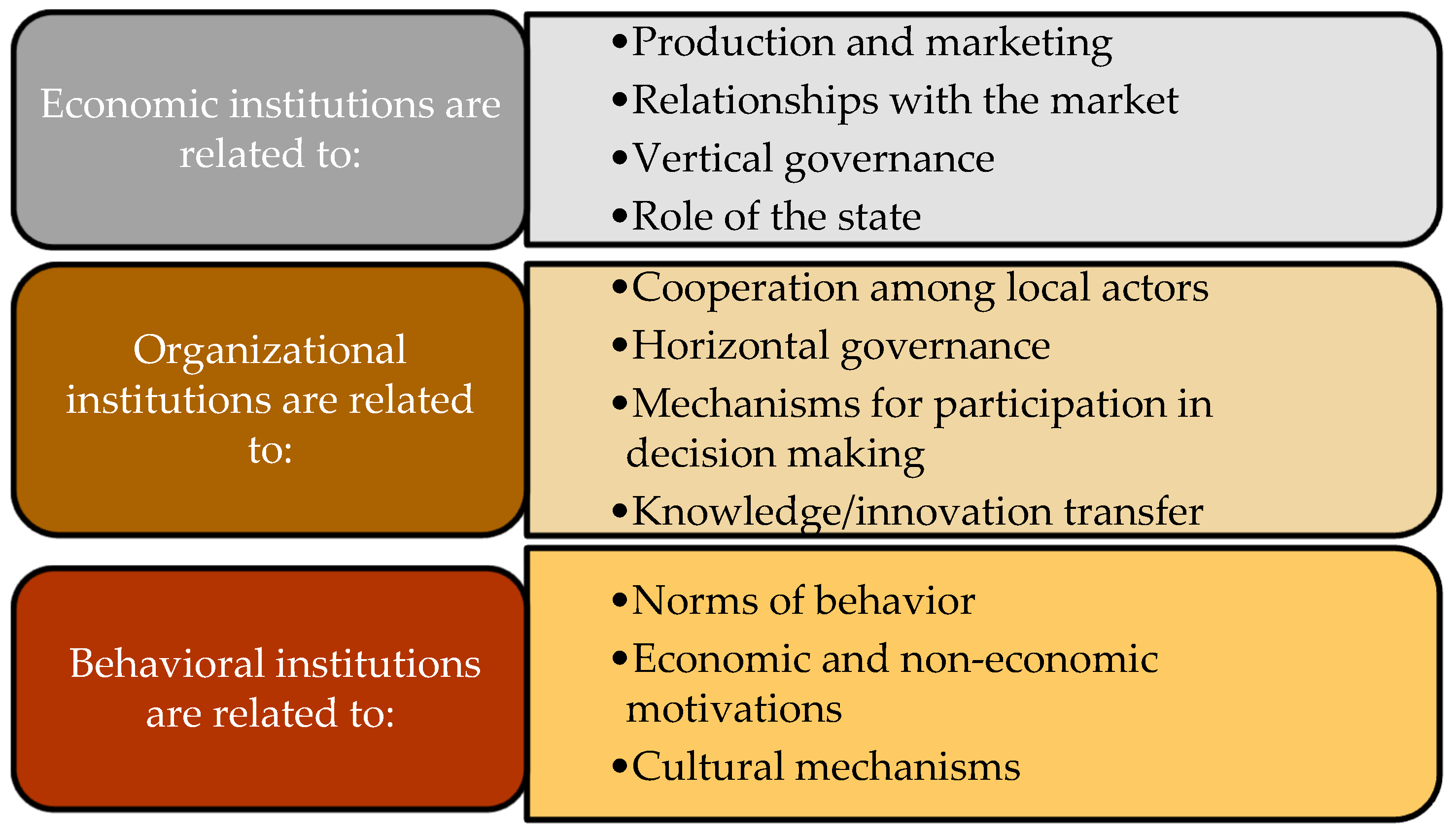

Notwithstanding the forces of flexible production organization, the development of cities, and the diffusion of innovations,

Vázquez-Barquero (

2007) categorically states that endogenous development occurs in territories whose institutions and culture stimulate economic progress and social transformations.

Development processes have deep cultural and institutional roots to the extent that firms and economic and social actors make investment decisions depending on the norms and rules in each territory. In this sense, various factors, such as the contracts and norms that regulate agreements, the population’s codes of behavior, governance, and culture, determine the development path of each territory (

Vázquez-Barquero & Rodríguez-Cohard, 2016).

Thus, according to

Costa (

2010), culture underpins institutions, and institutions determine transaction costs and access to information in an economy. This ultimately determines whether there is an environment conducive to development. This justifies the relationship between societies’ institutional environments and their potential for economic growth.

Institutional development also depends on cooperation among local actors and a democratic environment that enables broad participation in economic decisions and development policies (

Vázquez-Barquero & Rodríguez-Cohard, 2016). Economies advance when institutions evolve to support agreements, contracts, and exchanges at low transaction costs. Institutional change thus becomes a key driver of development, shaping production, trade relations, and investment decisions (

Vázquez-Barquero, 2010).

Vázquez-Barquero’s institutional perspective brings the institutional debate into territorial economic development, emphasizing that local institutions—both formal and informal—shape productive organization, innovation, and governance. Combined with Douglass North’s institutional theory, this approach deepens our understanding of institutions as historical structures that influence incentives and long-term economic performance.

2.3. Institutional Change by Douglass North

Vázquez-Barquero’s understanding of institutional flexibility as a condition for the development of economies is closely related to the experience of institutional change insofar as institutions are flexible due to their transformative power. Thus, it is essential to have a more detailed understanding of institutions and institutional change from the institutionalist theoretical framework itself

1.

Lopes (

2013) states that institutionalist theory is key not only to understanding how the economy works but also to analyze how institutional change affects people’s lives and production systems across countries. To explore institutions and institutional change, this study adopts the new institutional economics theory, especially Douglass North’s theory, which aligns with Vázquez-Barquero’s view on institutional flexibility and transformation.

Both North and Vázquez-Barquero see institutional change as central to economic development. They argue that institutions can lower production and transaction costs, enhance entrepreneurship, and foster cooperation among local actors. These institutionalist perspectives challenge neoclassical economics by emphasizing the role of institutions, the importance of historical context, and the diversity of growth paths (

Conceição, 2008). In this view, institutions act as mechanisms that drive development within specific times and places (

Conceição, 2002a).

New institutional economics (NIE) is one of the institutionalist theoretical streams recognized for the works of Ronald Coase, Oliver Williamson, and Douglass North. In “The Nature of the Firm”,

Coase (

1937) laid the foundations of NIE by justifying the existence of firms based on the reduction of transaction costs, which was later expanded upon by Williamson in the development of a theory of transaction costs.

New institutional economics presents two complementary approaches. The first, developed by Douglass North, is macro-institutional in scope and focuses on the origin, structure, and evolution of institutions—understood as the rules that shape societal behavior. The second, which is micro-institutional in nature, is linked to the economics of organizations and examines the variety of institutional arrangements. Both approaches treat institutions as central to analysis, with the micro perspective viewing the firm as a nexus of contracts (

Zylbersztajn, 2005, p. 397).

Conceição (

2002a) explains that NIE is built on three interconnected concepts, namely bounded rationality, opportunism, and transaction costs. Transaction costs arise because economic behavior is limited by rationality and influenced by opportunism—both of which reflect market imperfections.

Bounded rationality refers to the impossibility of knowing all the necessary information to make optimal decisions, with the understanding that agents make decisions as reasonably as possible in pursuing specific goals, given informational poverty (

Gala, 2003). On the other hand, opportunism manifests in the weakness of reason itself, understood as the pursuit of self-interest with guile (

Conceição, 2002b).

Therefore, the “economics of transaction costs” and industrial organization define the institutional environment—and, consequently, the institutions — that guide the decision-making process in a context permeated by uncertainty, bounded rationality, and opportunism, aiming to reduce transaction costs (

Conceição, 2002b, p. 131).

Although North also uses the concept of transaction costs, he broadens the institutional analysis to understand institutional change as a determining factor in economic development. For North, “the trajectories of institutional changes are essential in defining the different forms of economic growth” (

Conceição, 2008, p. 95).

The primary objective of Douglass

North (

1990) was to provide a theoretical framework to analyze the influence of institutions on the performance of economies. Institutions affect the performance of economies through their impact on transaction and production costs. Thus, “Douglass North’s institutionalist works begin by demonstrating the failures of neoclassical theory in addressing the determinants of economic performance throughout history” (

Lopes, 2013, p. 622). In other words, North identified that neoclassical theory did not consider the existence of information costs and the uncertainty in investing, Thus, it could have been more effective at explaining the reasons behind different economic performances over time (

Lopes, 2013).

According to

North (

1990), institutions can be formal (laws and rules) or informal (conventions, codes of conduct, behavioral norms), serving as guides for human action. Their main function is to reduce uncertainty by creating a stable—though not always efficient—framework for interaction. Ultimately, institutions define a society’s incentive structure, meaning that its performance depends on both institutions and the incentives they create for innovation and efficiency (

Lopes, 2013).

Years after presenting this initial definition of institutions, North expanded the concept of institutions in a new work written by Wallis and Weingast. They defined institutions as the rules of the game, “but not only in the sense of norms, as they would include formal laws, informal norms of behavior, and the beliefs shared by individuals about the world” (

North et al., 2009;

Bins, 2019, p. 18).

Regarding informal institutions,

North (

1990) clarifies that they originate from socially transmitted information and are part of the heritage we call culture. According to

North (

1990), informal constraints that are culturally derived will not change immediately in response to changes in formal rules, suggesting the prevalence of informal constraints over formal ones.

According to

Lopes (

2013), Douglass North links economic performance to three key factors shaping institutions and their change, namely learning, shared mental models, and evolving beliefs. For

North (

2005), institutions reflect the beliefs a society accumulates over time, making institutional change an incremental process shaped by historical constraints.

North (

2005) argues that institutions mirror prevailing societal beliefs. Thus, market structures reflect the interests of those in power—whether to maintain monopolies or promote competition. Beliefs guide individual actions, which may either preserve or transform institutional structures, influencing the potential for economic growth (

Lopes, 2013).

In this context, path dependence explains how institutional evolution is shaped by cultural legacies, learning, and mental models. Present choices are limited by past institutional frameworks, which also give rise to organizations. These organizations often resist changes that threaten their survival (

North, 2005).

Nonetheless, organizations—political, economic, social, or educational—are key agents in society. They arise from the existing institutional framework and pursue goals shaped by available incentives. Thus, economic performance and institutional change result from the interaction between organizations and institutions (

Gala, 2003).

Thus, understanding institutional change in Douglass North implies analyzing the interaction between agents represented by organizations and the existing institutional framework. In other words, economies’ performance results from the choices of agents interacting with the existing institutional framework, which is changing over time. In turn, agents’ choices result from their shared beliefs, which arise from mental models and evolve through learning (

Lopes, 2013).

For

North (

2005), institutions generally change incrementally as entrepreneurs and political and economic organizations perceive new opportunities or react to new threats that affect their well-being. Thus, institutional change can result from changes in formal rules or informal rules or the enforcement of either.

In this sense, long-term economic change is a “cumulative consequence” of various short-term decisions made by organizations and politicians that ultimately determine, directly or indirectly, economic performance (

Conceição, 2008). The economic and institutional change process, in turn, must encompass the following aspects: “uncertainty in a non-ergodic world; belief systems, culture, and cognitive science; human awareness and intentionality” (

Conceição, 2008, p. 96).

When questioning how institutions change,

North (

2005, p. 59) suggests that institutional change follows five propositions, as follows:

The key to institutional change is the continuous interaction between institutions and organizations in an economic setting of scarcity and, hence, competition.

Competition forces organizations to continually invest in skills and knowledge to survive. The kinds of skills and knowledge that individuals and their organizations acquire will shape evolving perceptions about opportunities and, hence, choices that will incrementally alter institutions.

The institutional framework provides the incentives that dictate the kinds of skills and knowledge perceived to have the maximum payoff.

Perceptions are derived from the mental constructs of the players.

An institutional matrix’s economies of scope, complementarities, and network externalities make institutional change overwhelmingly incremental and path-dependent.

North (

2005) emphasizes the distinction between institutions (the rules of the game) and organizations (the players), defining institutional change as the result of their interaction. Organizations—such as firms, unions, cooperatives, or political parties—are formed by individuals pursuing shared goals. The institutional matrix shapes which types of organizations can emerge.

Institutional change occurs when organizational actors, facing market competition, identify new opportunities. They may then seek to change the rules—either through political processes or by pressuring for better enforcement of existing norms or sanctions.

The second proposition highlights competition as a key driver of institutional change. Scarcity and rivalry push organizations to invest in skills and knowledge to enhance efficiency and survive (

North, 2005). When competition is weak or absent, there is little incentive for innovation, and institutional change tends to stagnate.

In this sense, North also emphasizes the importance of knowledge for the evolution of societies, as follows:

[..] The stock of knowledge the individuals in a society possess is the deep underlying determinant of the performance of economies and societies, and changes in that stock of knowledge are the key to the evolution of economies. […] The key point is that learning by individuals and organizations is the major influence on the evolution of institutions.

The third proposition states that a society’s incentive structure—its institutions—determines which types of organizations emerge and whether they are motivated to invest in skills and knowledge. For instance, when higher productivity leads to greater profits, organizations are more likely to invest in improving their capabilities (

North, 2005).

In the fourth proposition,

North (

2005) emphasizes that individuals’ choices depend on how they perceive their environment, shaped by mental models. These models arise from cultural background, local experiences, and external learning, meaning people from different contexts may interpret the same reality in different ways.

The fifth proposition highlights the mutual dependence between institutions and organizations. An organization’s success relies on the institutional framework that enables its existence. Thus, institutional change tends to be incremental and path-dependent—resisted by those it may harm and shaped by the knowledge and skills that organizations have already developed (

North, 2005).

Based on these five propositions and the characterization of institutional change,

North (

2005) believes he has built the fundamental foundation for understanding economic change. These propositions should guide the analysis of institutional change as a determining factor in endogenous development.