Dynamics Between Multidimensional and Monetary Poverty in Brazil: From Deprivation to Freedom

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical and Empirical Aspects

3. Methodology

3.1. Data and Measurement of Multidimensional and Unidimensional Poverty

3.2. Multinomial Logit Regression

4. Results

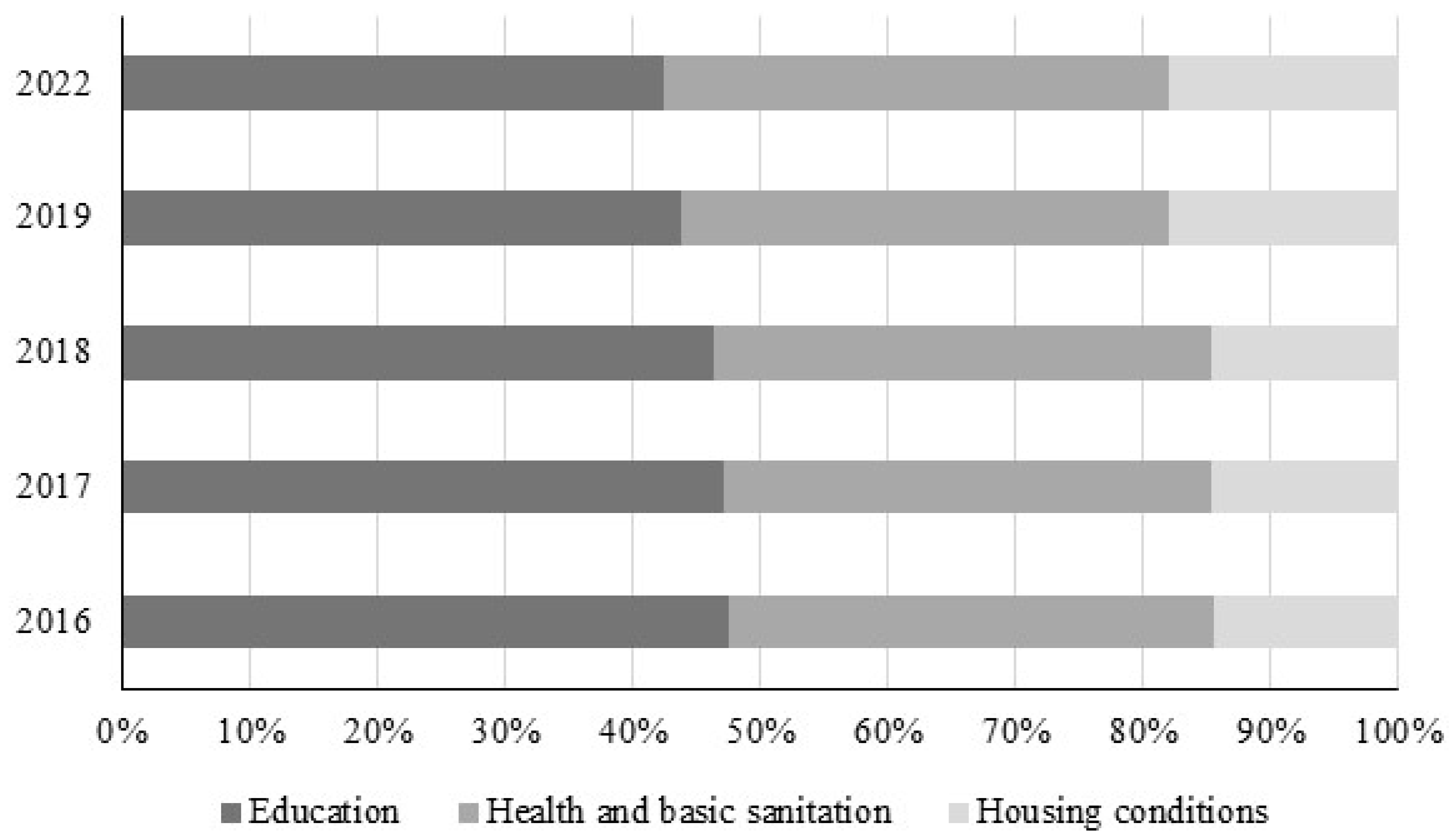

4.1. Multidimensional and Unidimensional Poverty Measures from 2015 to 2022

4.2. Relationship Between Multidimensional and Monetary Poverty

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Albuquerque, M. R., & Cunha, M. S. (2012). Uma análise da Pobreza sob o enfoque multidimensional no Paraná. Revista de Economia, 38(3), 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkire, S., Apablaza, M., Chakravarty, S., & Yalonetzky, G. (2017). Measuring chronic multidimensional poverty. Journal of Policy Modeling, 39, 983–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkire, S., & Fang, Y. (2019). Dynamics of multidimensional poverty a unidimensional income poverty: An evidence stability analysis from China. Social Indicator Research, 142, 25–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkire, S., & Foster, J. (2009). Counting and muldimensional poverty measurement. Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative, University of Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Alkire, S., Foster, J., Seth, S., Santos, M. E., Roche, J. M., & Ballon, P. (2015). Multidimensional poverty measurement and analysis. Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative, University of Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Alkire, S., & Santos, M. E. (2010). Acute multidimensional poverty: A new index for developing countries. University of Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, A. V., & Duflo, E. (2021). A economia dos pobres: Uma nova visão sobre a desigualdade. Zahar. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, R. P., Carvalho, M., & Franco, S. (2006). Pobreza multidimensional no Brasil. IPEA. [Google Scholar]

- Bárcena-Martín, E., Pérez-Moreno, S., & Rodríguez-Díaz, B. (2020). Rethinking multidimensional poverty through a multi-criteria analysis. Economic Modelling, 91, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkiss, M., Pauli, R. I. P., & Oliveira, S. V. (2021, December 6–10). Pobreza multidimensional na pandemia do Covid-19: Uma aplicação do método Alkire-Foster (AF) para o caso brasileiro. Encontro Brasileiro de Economia, São Paulo, Brazil. Available online: https://www.anpec.org.br/encontro/2021/submissao/files_I/i12-99217de2f6e784f101d03e19fe924ec0.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Bourguignon, F., & Chakravarty, S. (2003). The measurement of multidimensional poverty. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 1, 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brambilla, M. A., & Cunha, M. S. (2021). Pobreza multidimensional no Brasil, 1991, 2000 e 2010: Uma abordagem espacial para os municípios brasileiros. Nova Economia, 31, 869–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil. (2013). Lei nº 12.796, de 4 de abril de 2013. Brasília. Available online: https://legis.senado.leg.br/norma/588172 (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Brasil. (2014). Lei nº 13.005, de 25 de junho de 2014. Brasília. Available online: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2014/lei/l13005.htm (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Brasil. (2020). Lei nº 14.026, de 15 de julho de 2020. Brasília. Available online: https://legislacao.presidencia.gov.br/atos/?tipo=LEI&numero=14026&ano=2020&ato=cfaATWE9EMZpWT417 (accessed on 15 May 2024).

- Brites, M., Marin, S. R., & Rohenkohi, J. E. (2022). Pobreza multidimensional fuzzy nos municípios brasileiros em 2010. Pesquisa e Planejamento Econômico, 52(2), 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2005). Microeconometrics: Methods and applications. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S., & Ravallion, M. (2013). More relatively—Poor people in a less absolutely—Poor world. Income Wealth, 59(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahel, M., & Teles, L. R. (2018). Medindo a pobreza multidimensional do estado de Minas Gerais, Brasil: Olhando para além da renda. Revista de Administração Pública, 52(3), 386–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahel, M., Teles, L. R., & Caminha, D. A. (2016). Para além da renda: Uma análise da pobreza multidimensional. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais, 31(92), e319205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtado, C. (2007). Formação econômica do Brasil. Companhia das Letras. São Paulo. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, W. H. (2018). Econometric analysis (8th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Gremaud, A. P., Vasconcelos, A. S., & Tonello, R. (2002). Economia brasileira contemporânea. Atlas. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, R., & Jesus, J. G. (2023). Pobreza no Brasil, 2012–2022. Revista Brasileira de Economia Social e do Trabalho, 5, e023010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, R., & Kageyama, A. (2006). Pobreza no Brasil: Uma perspectiva multidimensional. Revista Economia e Sociedade, 15(1), 79–113. [Google Scholar]

- IBGE—Instituto Brasileiro de Geográfia e Estatística. (2023). Síntese de indicadores sociais: Uma análise das condições de vida da população brasileira. IBGE. [Google Scholar]

- IBGE—Instituto Brasileiro de Geográfia e Estatística. (2024). Censo demográfico 2022. IBGE. [Google Scholar]

- Marcelino, G. C., & Cunha, M. S. (2024). Multidimensional poverty in Brazil: Evidences for rural and urban areas. Revista de Economia e Sociologia Rural, 62(1), e266430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, M. C. (2022). Mapa da nova pobreza (40p). FGV Social. [Google Scholar]

- Neves, O. J. F., & Silva, A. M. R. (2023). The effects of muldimensional well-being growth on poverty and inquality in Brazil over the periods of 2004–2008 and 2016–2019. Brazilian Journal of Political Economy, 43(2), 358–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ONU—Organização das Nações Unidas. (2015). Transformando nosso mundo: A agenda 2030 para o desenvolvimento sustentável. Available online: https://brasil.un.org (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Pereira, O. L. F., Santos, V. F. S., Silva, G. J., & Oliveira, S. V. (2020). Sobre el futuro y la juventud de Brasil: Un análisis de la incidencia de la pobreza multidimensional en las grandes regiones. Revista Apuntes, 47(86), 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, L. P., & Taques, F. H. (2012). Pobreza: Da insuficiência de renda à privação de tempo. Revista de Desenvolvimento Econômico, XIV(25), 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, S. (2006). Pobreza no Brasil: Afinal do que se trata? (3rd ed.) FGV. Available online: https://books.google.rs/books?hl=sr&lr=&id=H4llDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA2&dq=Rocha,+S.+(2006).+Pobreza+no+Brasil:+Afinal+do+que+se+trata%3F+(3nd+Ed.).+FGV,+244.&ots=KxU7mvoHch&sig=zQwFhkWTIXsC7fhoRH1BvVta95c&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 23 January 2024).

- Rosa, S. S. D., Bagolim, I. P., & Ávila, R. P. (2023). Multidimensional poverty in Brazil’s north region. International Journal of Social Economics, 50(5), 725–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAGICAD (Secretaria de Avaliação, Gestão da Informação e Cadastro Único). (2024). Programa auxílio Brasil—Quantidade de famílias e valores do Auxílio Brasil. Available online: https://aplicacoes.cidadania.gov.br/vis/data3 (accessed on 23 January 2024).

- Salama, P., & Destremau, B. (1999). O tamanho da pobreza. Economia política de distribuição de renda (p. 160). Grammont. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. (1993). Capability and well-being. In A. Sen, & M. Nussbaum (Eds.), The quality of life (pp. 30–55). Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A., & Anand, S. (1997). Concepts of human development and poverty: A multidimensional perspective. In ONU (Ed.), Poverty and human development (pp. 1–20). United Nations Development Programme. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. K. (2000). Desenvolvimento como Liberdade. Companhia Das Letras. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, A. F., Sousa, J. S., & Araujo, J. A. (2017). Evidências sobre a pobreza multidimensional na região Norte do Brasil. Revista de Administração Pública, 51(2), 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A. M. R., Lacerda, F. C. C., & Neder, H. D. (2011). A evolução do estudo da pobreza: Da abordagem monetária à privação de capacitações. Bahia Análise & Dados, 21(3), 509–527. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J. J., Bruno, M. A. P., & Silva, D. B. N. (2020). Pobreza multidimensional no Brasil: Uma análise do período 2004–2015. Revista de Economia Política, 40(1), 138–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L. O. (1996). Terras devolutas e latifúndio: Efeitos da Lei de 1850. Editora da UNICAMP. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, P. H. G. F., Osorio, R. G., Paiva, L. H., & Soares, S. (2019). Os efeitos do programa bolsa família sobre a pobreza e a desigualdade: Uma balança dos primeiros quinze years (38p). IPEA. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, P. (1993). The international analysis of poverty. Harvester Wheatsheaf. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP & OPHI. (2019). Illuminating inequalities. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI), University of Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP & OPHI. (2023). Unstacking global poverty—Data for high-impact action (31p). United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI), University of Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Valente, X. (2023). La pobreza en Venezuela: Conceptos, medidas y políticas de los enfoques tradicionales. Revista Venezolana de análisis de conjuntura, XXIV(1), 9–42. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, C. A., Kuhn, D. D., & Marin, S. R. (2017). Método Alkire-Foster: Uma aplicação para a medição de pobreza multidimensional no Rio Grande do Sul (2000–2010). Planejamento e Políticas Públicas, 48, 267–299. [Google Scholar]

| Categories | Multidimensional Poverty | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor | Non Poor | ||

| Unidimensional poverty | Poor | Chronic poverty | Situational poverty |

| Non-poor | Structural poverty | Socially integrated | |

| Dimension/Indicators | Description | Weight |

|---|---|---|

| Education | 1/3 | |

| School attendance | Homes with at least one child or teenager between six and seventeen years old who is not in school. | 1/9 |

| Schools delay | Household that includes a young person who has not yet graduated from high school. | 1/9 |

| Years of study | Household where no adult resident has finished primary school. | 1/9 |

| Health and basic services | 1/3 | |

| Water supply | A residence without access to running water in at least one room supplied by a general distribution network, well, or spring. | 1/12 |

| Garbage destination | Household that does not use a cleaning services for garbage collection. | 1/12 |

| Electricity | Household lacking main electricity, generator, or solar lighting. | 1/12 |

| Sanitary sewage | Household with a toilet that is not connected to the sewage or rainwater network. | 1/12 |

| Housing conditions | 1/3 | |

| Density | A household where three or more people share a bedroom. | 1/12 |

| Ceiling material | Household with a roof primarily made of materials other than tiles, concrete slabs, or construction-grade wood. | 1/12 |

| Fuel | Household that cooks without gas or electricity. | 1/12 |

| Durable goods | Household that does not have more than one of the following items: refrigerator, television (color or black and white), telephone (landline or cell phone), washing machine, personal computer, and automobile. | 1/12 |

| Dimension/Indicattor | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | |||||

| School attendance | 21.22 | 21.03 | 19.37 | 17.47 | 15.66 |

| School delay | 62.22 | 62.05 | 61.84 | 58.21 | 54.88 |

| Years of study | 91.61 | 90.38 | 89.96 | 88.67 | 85.99 |

| Health and basic sanitation | |||||

| Water supply | 27.65 | 27.18 | 27.84 | 26.18 | 29.81 |

| Garbage disposal | 70.32 | 70.30 | 70.08 | 71.32 | 72.58 |

| Electricity | 4.03 | 4.21 | 4.50 | 4.64 | 4.22 |

| Sanitary sewage | 85.52 | 86.80 | 89.39 | 88.52 | 88.85 |

| Housing conditions | |||||

| Density | 52.67 | 52.19 | 54.12 | 51.20 | 49.83 |

| Ceiling material | 13.40 | 14.49 | 13.17 | 13.29 | 16.29 |

| Fuel | 0.80 | 1.23 | 1.32 | 20.82 | 18.56 |

| Durable goods | 4.02 | 4.06 | 3.65 | 4.35 | 3.79 |

| Year | Multidimensional Poverty | Monetary Poverty | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M0 | H | A | PE | P | |

| 2016 | 0.0203 | 0.0495 | 0.4098 | 0.1263 | 0.3064 |

| 2017 | 0.0193 | 0.0471 | 0.4098 | 0.1271 | 0.2961 |

| 2018 | 0.0181 | 0.0441 | 0.4102 | 0.1259 | 0.2900 |

| 2019 | 0.0184 | 0.0443 | 0.4162 | 0.1242 | 0.2819 |

| 2022 | 0.0134 | 0.0326 | 0.4105 | 0.1079 | 0.2814 |

| Group | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic (CRN) | 3.93 | 3.64 | 3.50 | 3.52 | 2.49 |

| Structural (EST) | 1.03 | 1.06 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.77 |

| Situational (CNJ) | 26.73 | 25.98 | 25.51 | 24.67 | 25.65 |

| Socially integrated (SCI) | 68.32 | 69.31 | 70.08 | 70.9 | 71.09 |

| Variable | 2016 | 2019 | 2022 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRN | EST | CNJ | CRN | EST | CNJ | CRN | EST | CNJ | |

| Woman | 1.139 *** | 1.007 | 1.157 *** | 1.150 *** | 0.976 | 1.178 *** | 1.151 *** | 1.001 | 1.194 *** |

| Non-white | 2.034 *** | 1.478 *** | 1.660 *** | 2.049 *** | 1.522 *** | 1.635 *** | 1.998 *** | 1.459 *** | 1.561 *** |

| 0 to 5 years | 43.719 *** | 3.375 *** | 20.367 *** | 64.364 *** | 2.869 *** | 27.691 *** | 46.943 *** | 3.668 *** | 16.274 *** |

| 6 to 10 years | 11.841 *** | 0.603 *** | 5.880 *** | 13.012 *** | 0.489 *** | 7.075 *** | 9.613 *** | 0.544 *** | 4.605 *** |

| 11 to 14 years | 11.284 *** | 0.696 *** | 5.445 *** | 12.860 *** | 0.649 *** | 6.567 *** | 8.585 *** | 0.580 *** | 4.189 *** |

| 15 to 17 years | 29.251 *** | 3.175 *** | 6.049 *** | 32.430 *** | 2.649 *** | 7.024 *** | 21.604 *** | 2.572 *** | 4.223 *** |

| 18 to 24 years | 74.017 *** | 12.217 *** | 5.859 *** | 92.226 *** | 11.465 *** | 7.203 *** | 66.518 *** | 12.836 *** | 4.189 *** |

| 25 to 29 years | 13.067 *** | 1.685 *** | 5.145 *** | 18.901 *** | 1.416 *** | 6.703 *** | 13.153 *** | 1.687 *** | 3.961 *** |

| 30 to 59 years | 6.657 *** | 1.111 *** | 3.754 *** | 8.209 *** | 0.984 | 4.580 *** | 6.159 *** | 1.108 *** | 3.035 *** |

| Less than 1 year | 3.812 *** | 4.283 *** | 3.625 *** | 3.622 *** | 4.767 *** | 3.118 *** | 3.943 *** | 5.230 *** | 3.266 *** |

| Primary incompl. | 3.590 *** | 3.765 *** | 5.051 *** | 4.334 *** | 4.218 *** | 5.338 *** | 4.651 *** | 4.910 *** | 4.957 *** |

| Primary complete | 1.059 | 1.290 *** | 3.733 *** | 1.368 *** | 1.463 *** | 4.264 *** | 1.610 *** | 1.471 *** | 4.228 *** |

| Second. incomp. | 0.783 *** | 1.257 *** | 3.445 *** | 1.102 ** | 1.426 *** | 3.999 *** | 1.331 *** | 1.428 *** | 4.147 *** |

| Second. Complete | 0.161 *** | 0.256 *** | 2.048 *** | 0.242 *** | 0.304 *** | 2.352 *** | 0.297 *** | 0.315 *** | 2.444 *** |

| College incomp. | 0.046 *** | 0.086 *** | 0.858 *** | 0.042 *** | 0.128 *** | 0.996 *** | 0.064 *** | 0.123 *** | 1.123 *** |

| Nuclear | 3721 *** | 0.789 *** | 2.460 *** | 1.815 *** | 0.643 *** | 1.683 | 1.687 *** | 0.576 *** | 1.703 *** |

| Extended | 5062 *** | 1.285 *** | 2.699 *** | 2.495 *** | 1.072 | 1.959 *** | 2.134 *** | 0.889 ** | 1.789 *** |

| Compound | 4701 *** | 2.031 *** | 2.234 *** | 1.897 *** | 1.355 *** | 1.632 *** | 2.058 *** | 1.007 *** | 1.314 *** |

| Rural | 11.832 *** | 11.923 *** | 1.871 *** | 13.954 *** | 15.054 *** | 1.839 *** | 13.392 *** | 14.629 *** | 1.663 *** |

| Metropolitan | 0.432 *** | 0.532 *** | 0.689 *** | 0.391 *** | 0.385 *** | 0.713 *** | 0.421 *** | 0.470 *** | 0.805 *** |

| North | 8.929 *** | 4.002 *** | 2.040 *** | 11.829 *** | 4.207 *** | 2.224 *** | 12.995 *** | 5.725 *** | 1.949 *** |

| Northeast | 5.965 *** | 2.675 *** | 2807 *** | 7.717 *** | 2.697 *** | 2.973 *** | 7.732 *** | 3.112 *** | 2.834 *** |

| South | 0.755 *** | 1.369 *** | 0.614 *** | 0.840 *** | 1.358 *** | 0.586 *** | 0.908 * | 1.617 *** | 0.595 *** |

| Center-West | 1.089 ** | 2.239 *** | 0.769 *** | 1.166 *** | 1.922 *** | 0.752 *** | 1.087 | 2.542 *** | 0.735 *** |

| Constant | 0.000 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.006 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.006 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.011 *** |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.2315 | 0.2456 | 0.2315 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cunha, M.S.d. Dynamics Between Multidimensional and Monetary Poverty in Brazil: From Deprivation to Freedom. Economies 2025, 13, 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13050142

Cunha MSd. Dynamics Between Multidimensional and Monetary Poverty in Brazil: From Deprivation to Freedom. Economies. 2025; 13(5):142. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13050142

Chicago/Turabian StyleCunha, Marina Silva da. 2025. "Dynamics Between Multidimensional and Monetary Poverty in Brazil: From Deprivation to Freedom" Economies 13, no. 5: 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13050142

APA StyleCunha, M. S. d. (2025). Dynamics Between Multidimensional and Monetary Poverty in Brazil: From Deprivation to Freedom. Economies, 13(5), 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13050142