Resilience and Asset Pricing in COVID-19 Disaster

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Contribution to Literature

3. Resilience

3.1. Workplace Resilience

3.2. Is Workplace Resilience Adequate Enough?

3.3. Financial Resilience

4. Model and Data

4.1. The Economy

4.2. Exogenous Dividend Stream

4.2.1. Workplace Resilience: Cross-Sectional Effect of COVID-19

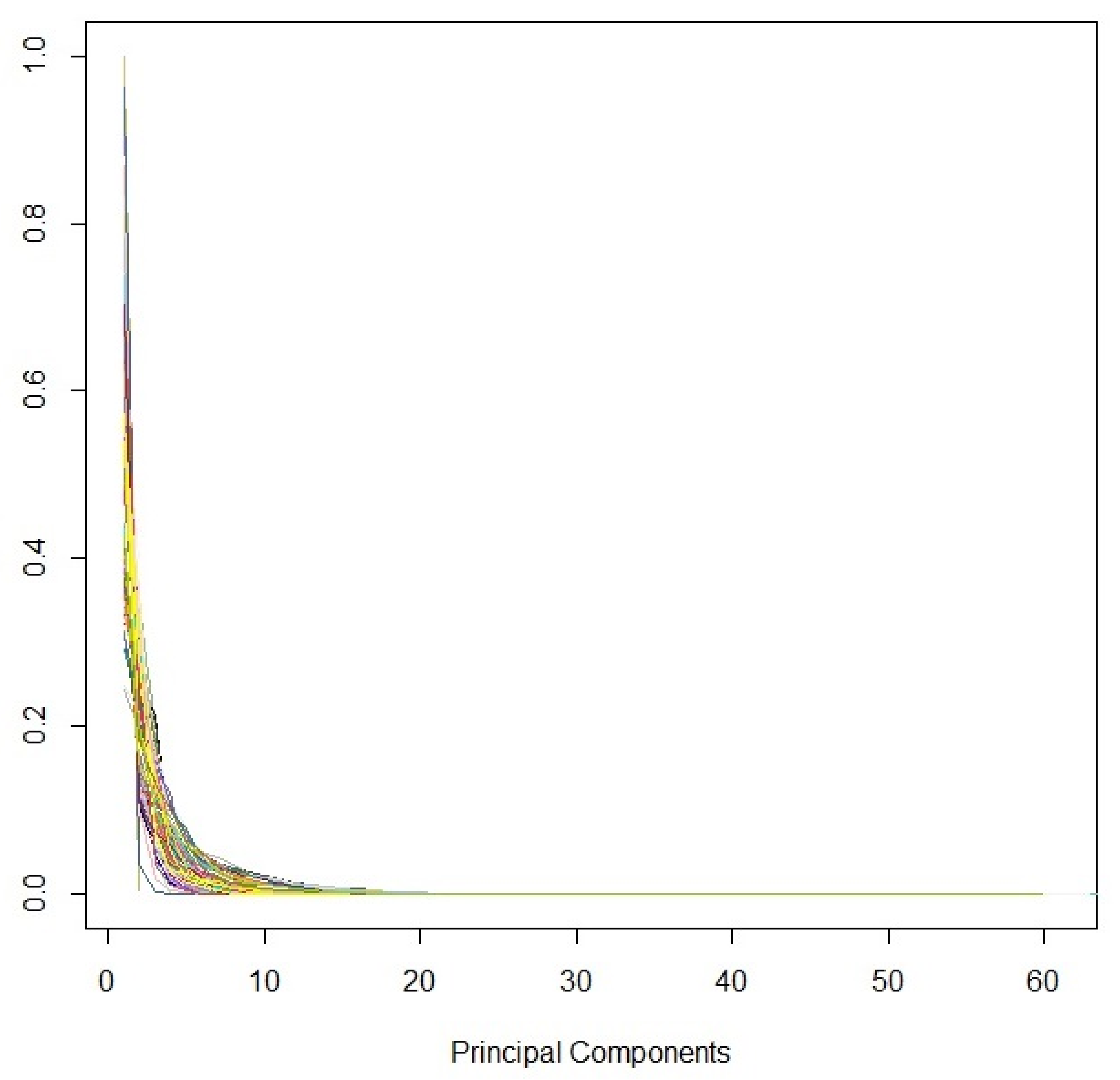

4.2.2. Financial Resilience: Dynamic Functional Principal Components

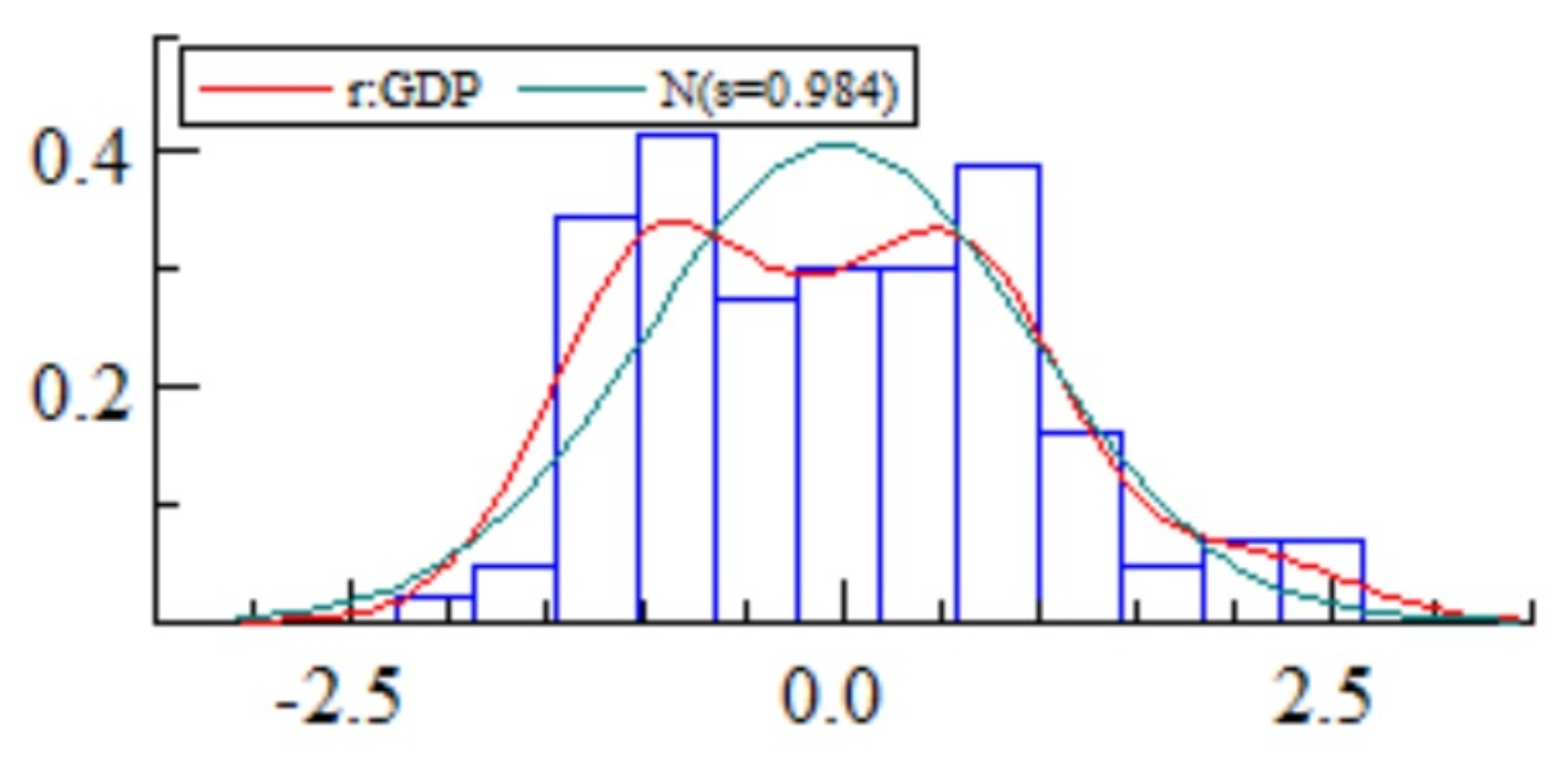

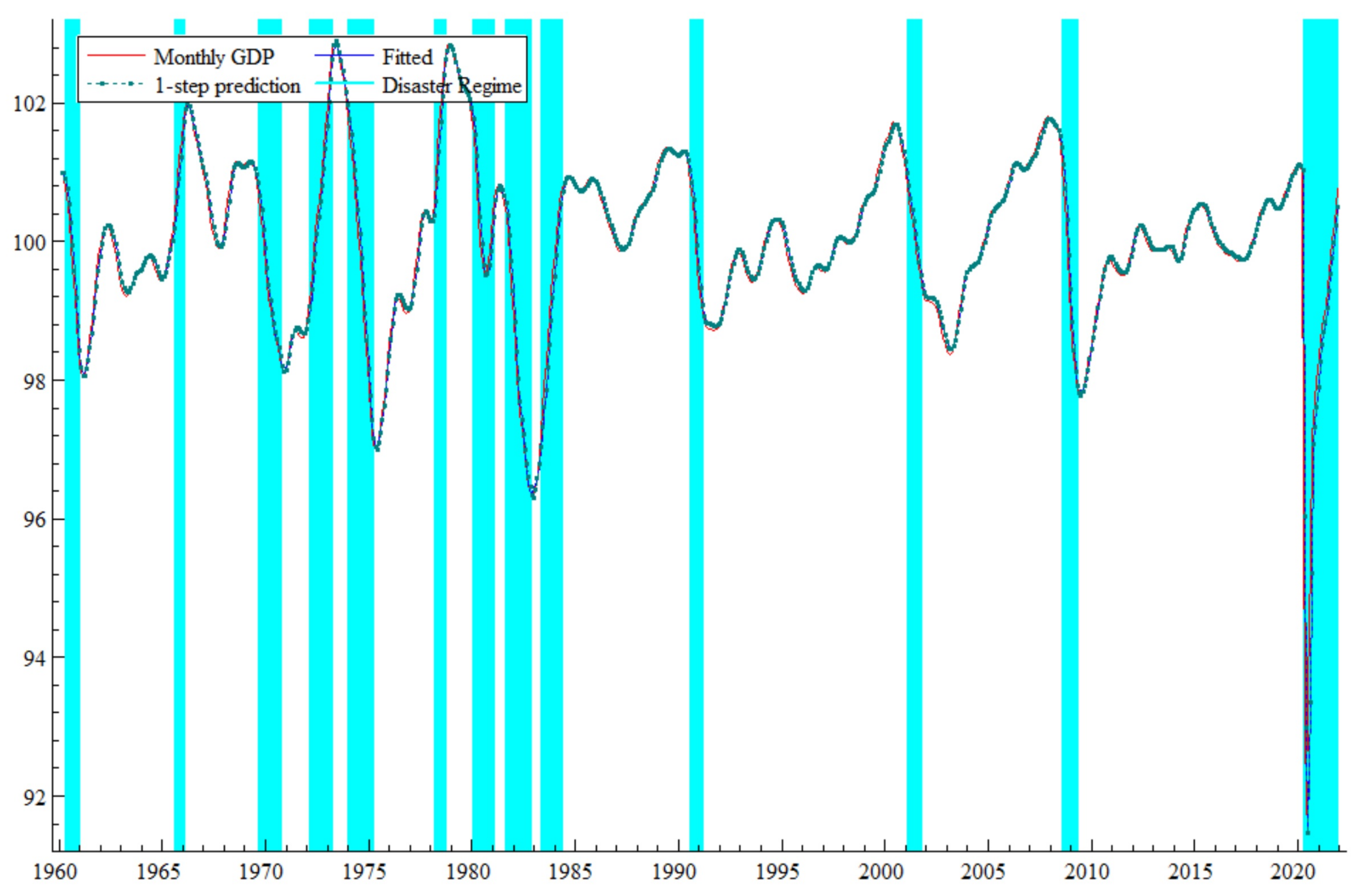

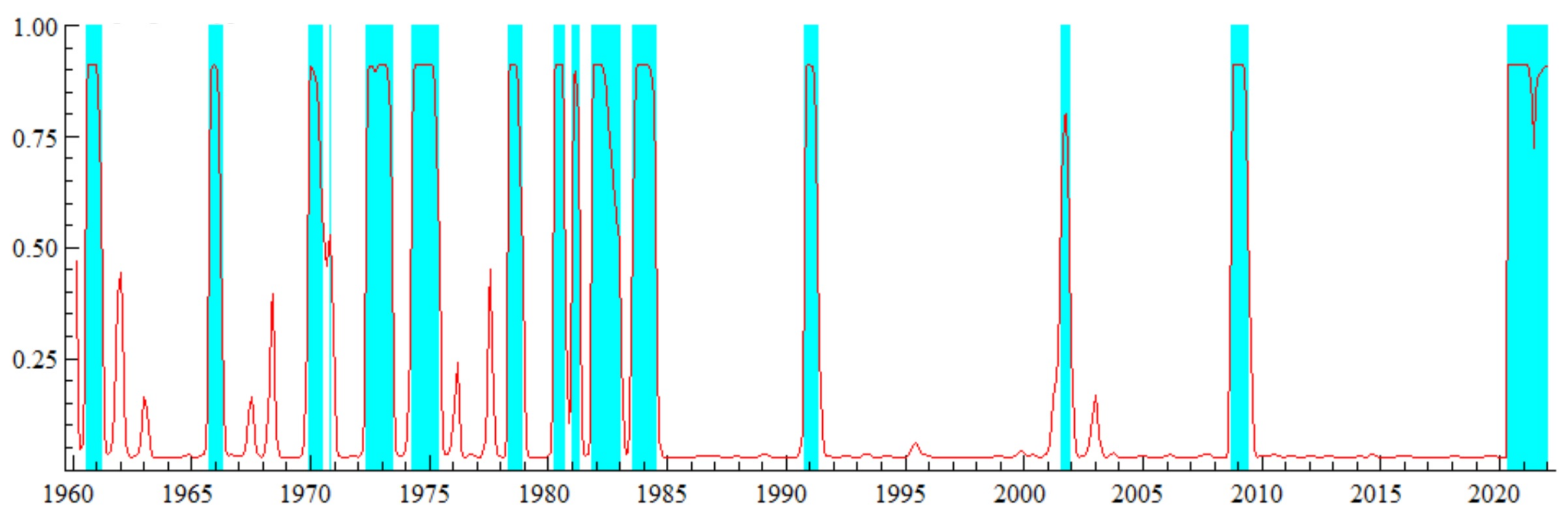

4.2.3. Macro Time Effect of COVID-19

4.2.4. Dividend Growth

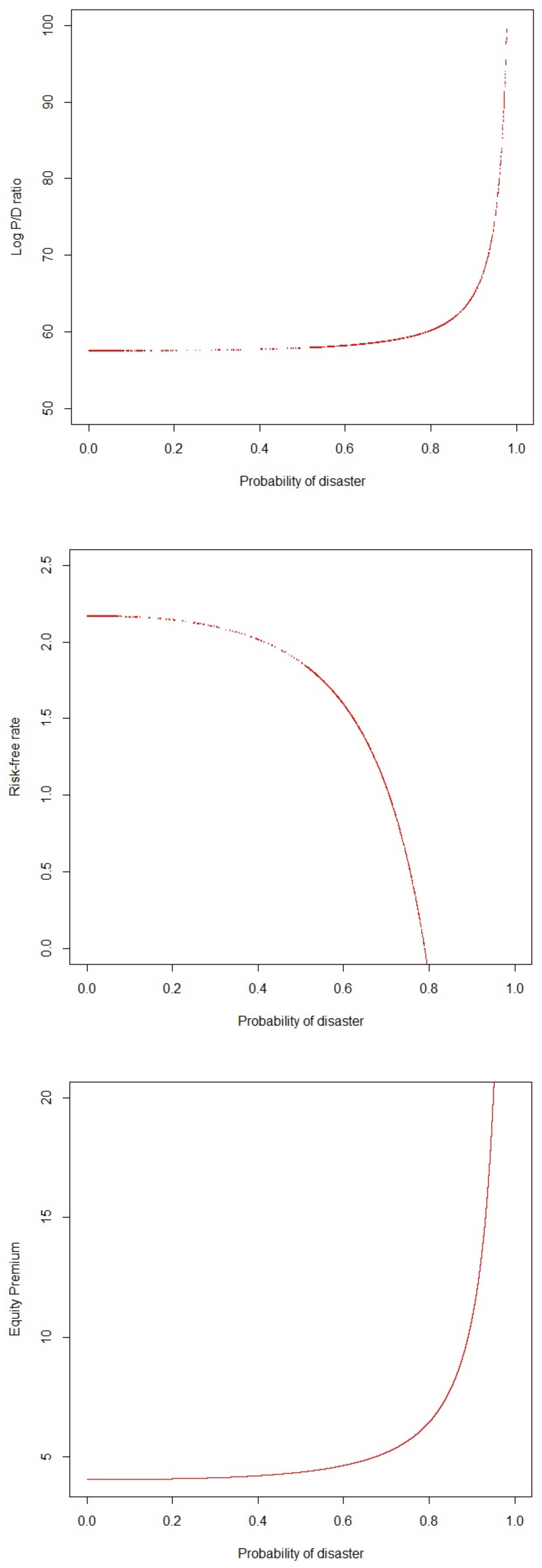

5. Solution of the Model

6. Results

6.1. Macroeconomic Sensitivity to COVID-19 Disaster

6.2. Justification for Dividend Stream and Asset-Pricing Moments

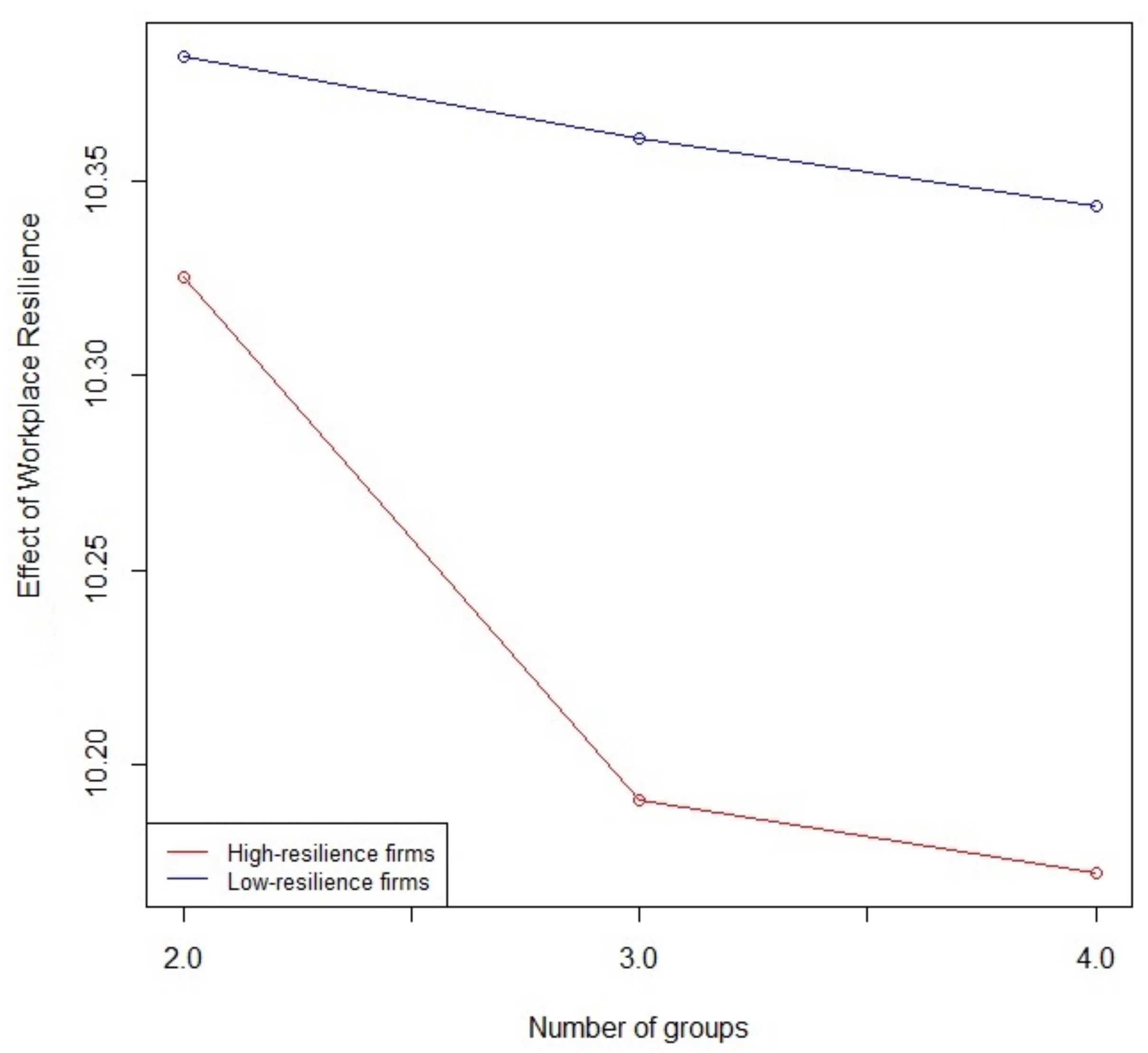

6.2.1. Interpretation of Workplace Resilience Impact

6.2.2. Interpretation of Macro Time Effect of COVID-19

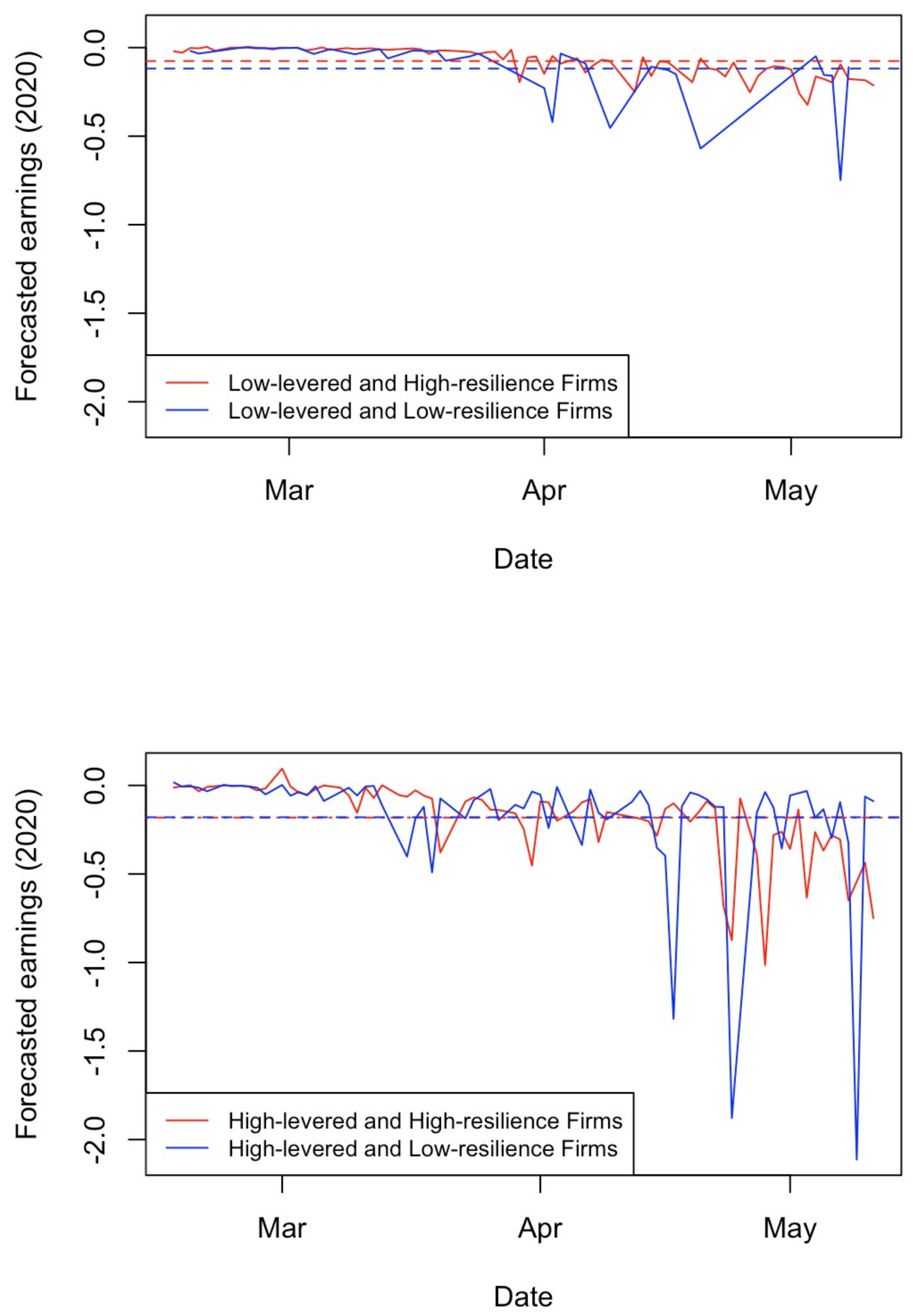

6.2.3. Interpretation of Financial Resilience

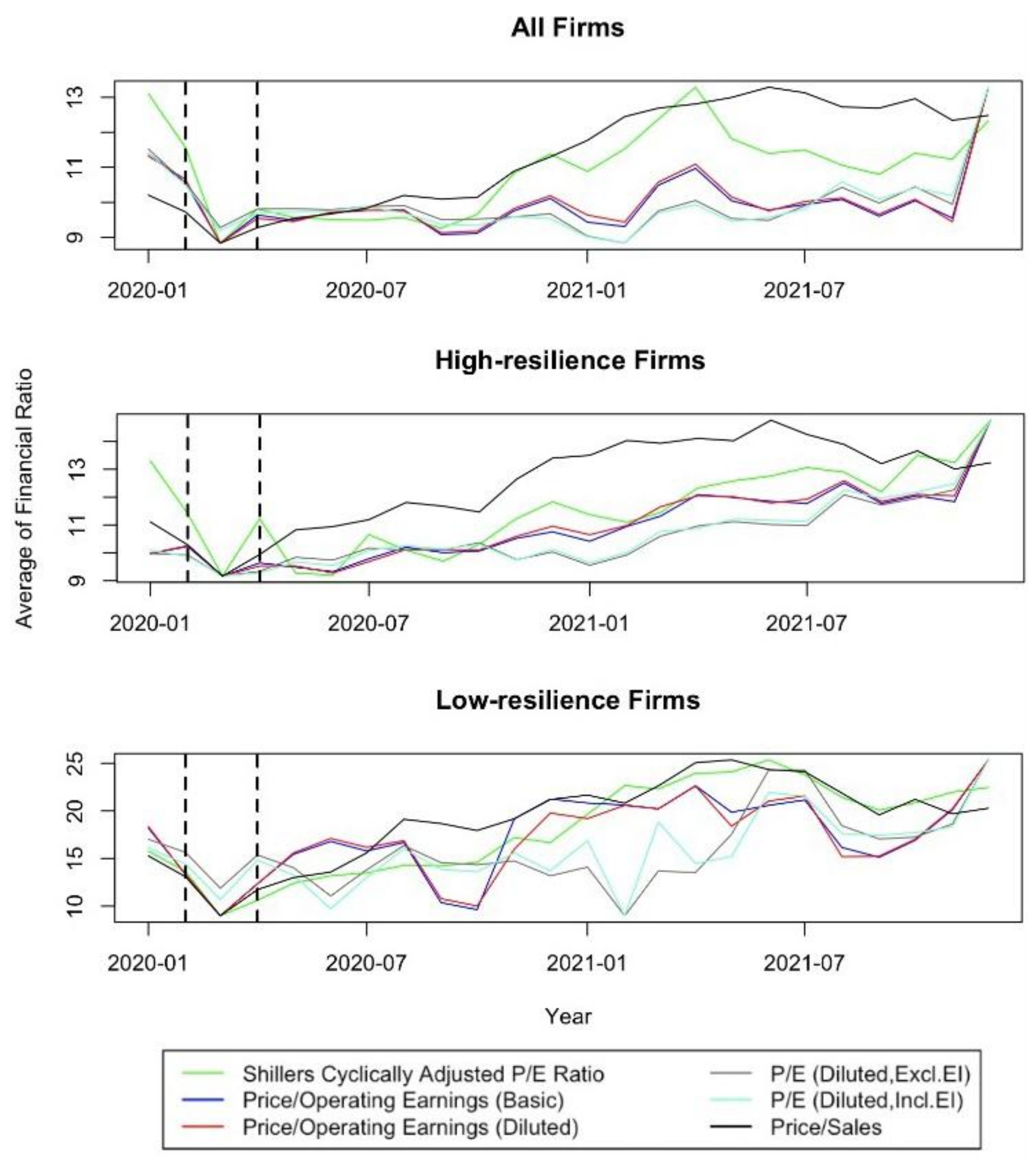

7. Major Elements of Financial Resilience

7.1. Valuation Ratios

7.2. Liquidity Ratio

7.3. Solvency Ratio

8. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Model Comparison | Lin vs. MS(2) | Lin vs. MS(3) | Lin vs. MS(4) | Lin vs. MS(5) | Lin vs. MS(6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR-Test | 1102.7 | 1413.4 | 1710.0 | 1790.3 | 1813.5 |

| Number of Regimes (i) | i = 2 | i = 3 | i = 4 | i = 5 | i = 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bayes factor () | 1 | 1.28 | 1.55 | 1.63 | 1.64 |

| Estimated Disaster Regimes | Estimated Duration | Reported by NBER/Fed or Related Publications |

|---|---|---|

| May 1960 to January 1961 | 9 | GDP was −2.1% in Q2 in 1960, rose by 2.0% in Q3, was down by 5.0% in Q4. |

| August 1965 to February 1966 | 7 | August 1965, the month of the so-called Credit Crunch in the financial markets, corporations and Federal Government agencies. |

| September 1969 to October 1970 | 14 | Economy contracted by 1.9% in Q4, and by 0.6% in Q1 1970, rose by 0.6% in Q2 and 3.7% in Q3, fell by 4.2% in Q4. |

| March 1972 to April 1973 | 14 | OPEC oil embargo leads to quadrupling oil prices: instituting wage-price controls. |

| January 1974 to April 1975 | 16 | OPEC oil embargo leads to quadrupling oil prices: Stagflation started in 1973 Q4, continued to 1975 Q1. |

| March 1978 to October 1978 | 8 | Due to unemployment trended down slightly by the end of the decade, inflation continued to rise, reaching 11 percent in June 1979 (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis). |

| February 1980 to February 1981 | 13 | Double whammy of two recessions: Oil shock of 1978-79 (Iranian oil embargo). |

| September 1981 to November 1982 | 15 | Raising interest rates to combat inflation by Fed. |

| May 1983 to May 1984 | 13 | Large federal budget deficit put upward pressure on interest rates. |

| August 1990 to March 1991 | 8 | Saving and loan crisis, higher interest rates and Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, July 1990 to March 1991. |

| February 2001 to October 2001 | 9 | Boom and subsequent bust in dot-com businesses, March to November 2001. |

| August 2008 to May 2009 | 10 | The great recession (subprime mortgage crisis, a global bank credit crisis), lasted in 2009. |

| April 2020 to December 2021 | 21 | COVID-19 pandemic crisis, the skyrocketing of unemployment rate. |

| Sector NAICS Code | Sectors | Panel Effect | Cross-Sectional Dependence | Heterogeneous Effect | Serrial Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Mining, Utility and Construction | + | + | + | + |

| 3 | Manufacturing | + | + | + | + |

| 4 | Trade, Transportation and Warehousing | + | + | + | + |

| 5 | Information, Finance, Insurance, Real State Rental, Scientific Services, Management and Remediation Services | + | + | + | + |

| 6 | Educational, Health Care and Social Assistance | + | + | + | + |

| Financial Ratio | Variable Name | Category |

|---|---|---|

| Capitalization Ratio | capital_ratio | Capitalization |

| Common Equity/Invested Capital | equity_invcap | Capitalization |

| Long-term Debt/Invested Capital | debt_invcap | Capitalization |

| Total Debt/Invested Capital | totdebt_invcap | Capitalization |

| Asset Turnover | at_turn | Efficiency |

| Inventory Turnover | inv_turn | Efficiency |

| Payables Turnover | pay_turn | Efficiency |

| Receivables Turnover | rect_turn | Efficiency |

| Sales/Stockholders Equity | sale_equity | Efficiency |

| Sales/Invested Capital | sale_invcap | Efficiency |

| Sales/Working Capital | sale_nwc | Efficiency |

| Inventory/Current Assets | invt_act | Financial Soundness |

| Receivables/Current Assets | rect_act | Financial Soundness |

| Free Cash Flow/Operating Cash Flow | fcf_ocf | Financial Soundness |

| Operating CF/Current Liabilities | ocf_lct | Financial Soundness |

| Cash Flow/Total Debt | cash_debt | Financial Soundness |

| Cash Balance/Total Liabilities | cash_lt | Financial Soundness |

| Cash-Flow Margin | cfm | Financial Soundness |

| Short-Term Debt/Total Debt | short_debt | Financial Soundness |

| Profit Before Depreciation/Current Liabilities | profit_lct | Financial Soundness |

| Current Liabilities/Total Liabilities | curr_debt | Financial Soundness |

| Total Debt/EBITDA | debt_ebitda | Financial Soundness |

| Long-term Debt/Book Equity | dltt_be | Financial Soundness |

| Interest/Average Long-term Debt | int_debt | Financial Soundness |

| Interest/Average Total Debt | int_totdebt | Financial Soundness |

| Long-term Debt/Total Liabilities | lt_debt | Financial Soundness |

| Total Liabilities/Total Tangible Assets | lt_ppent | Financial Soundness |

| Cash Conversion Cycle (Days) | cash_conversion | Liquidity |

| Cash Ratio | cash_ratio | Liquidity |

| Current Ratio | curr_ratio | Liquidity |

| Quick Ratio (Acid Test) | quick_ratio | Liquidity |

| Accruals/Average Assets | Accrual | Other |

| Research and Development/Sales | RD_SALE | Other |

| Avertising Expenses/Sales | adv_sale | Other |

| Labor Expenses/Sales | staff_sale | Other |

| Effective Tax Rate | efftax | Profitability |

| Gross Profit/Total Assets | GProf | Profitability |

| After-tax Return on Average Common Equity | aftret_eq | Profitability |

| After-tax Return on Total Stockholders’ Equity | aftret_equity | Profitability |

| After-tax Return on Invested Capital | aftret_invcapx | Profitability |

| Gross Profit Margin | gpm | Profitability |

| Net Profit Margin | npm | Profitability |

| Operating Profit Margin After Depreciation | opmad | Profitability |

| Operating Profit Margin Before Depreciation | opmbd | Profitability |

| Pre-tax Return on Total Earning Assets | pretret_earnat | Profitability |

| Pre-tax return on Net Operating Assets | pretret_noa | Profitability |

| Pre-tax Profit Margin | ptpm | Profitability |

| Return on Assets | roa | Profitability |

| Return on Capital Employed | roce | Profitability |

| Return on Equity | roe | Profitability |

| Total Debt/Equity | de_ratio | Solvency |

| Total Debt/Total Assets | debt_assets | Solvency |

| Total Debt/Total Assets | debt_at | Solvency |

| Total Debt/Capital | debt_capital | Solvency |

| After-tax Interest Coverage | intcov | Solvency |

| Interest Coverage Ratio | intcov_ratio | Solvency |

| Dividend Payout Ratio | dpr | Valuation |

| Forward P/E to 1-year Growth (PEG) ratio | PEG_1yrforward | Valuation |

| Forward P/E to Long-term Growth (PEG) ratio | PEG_ltgforward | Valuation |

| Trailing P/E to Growth (PEG) ratio | PEG_trailing | Valuation |

| Book/Market | bm | Valuation |

| Shillers Cyclically Adjusted P/E Ratio | capei | Valuation |

| Dividend Yield | divyield | Valuation |

| Enterprise Value Multiple | evm | Valuation |

| Price/Cash flow | pcf | Valuation |

| P/E (Diluted, Excl. EI) | pe_exi | Valuation |

| P/E (Diluted, Incl. EI) | pe_inc | Valuation |

| Price/Operating Earnings (Basic, Excl. EI) | pe_op_basic | Valuation |

| Price/Operating Earnings (Diluted, Excl. EI) | pe_op_dil | Valuation |

| Price/Sales | ps | Valuation |

| Price/Book | ptb | Valuation |

| 1 | This type of preference could better capture the investors’ preference in an uncertain situation like COVID-19. The results of the calibration exercise support this, although the Euler equation is a general form of power-utility function with a specific version of EZ preferences. |

| 2 | Term “resilience” without mentioning its type, refers to workplace intuition of resilience. |

| 3 | This paper considers analysts’ earnings expectation as a proxy for future cash flows, following Daadmehr (2024) and Landier and Thesmar (2020). |

| 4 | Implicitly, it assumes is equal to production (all output is consumed at each time) and the risky asset pays , which is a claim to aggregate consumption in each period t. |

| 5 | Equation (1) is the simplified version of Equation (13) in Campbell (1993), with constant gross simple return on wealth invested from period t to period t + 1, as an additional assumption to be able to solve the model analytically (Appendix A). This can be considered realistic due to two separate pieces of evidence: (1) Ghaderi et al. (2022) show the wealth-to-consumption ratio varies almost not significantly by time-varying beliefs. (2) The wealth-to-consumption ratio varies with interest rates (Lustig et al., 2013), and interest rates did not affect either the market crash or the market rebound in COVID time (Cox et al., 2020). Moreover, the model and calibration exercise are in line with Barro (2006), who fully explains that the EZW framework ends up as simple as the power-utility setting, and it is in accordance with a broader set of asset-pricing facts. |

| 6 | To compute empirical spectral density, this paper considers Bartlett kernel (e.g., Brockwell and Davis (1991)). |

| 7 | The letter, s is used to emphasize that the overall contraction depends on the state of the economy. It is eliminated for ease in the rest of this subsection. |

| 8 | Statistical tests provided in the Appendix A (Table A1) guarantee the existence of significant regime switching in the COVID-19 outbreak. Table A1 summarizes the results of the Likelihood Ratio Test (LRT) of the linearity of the model. The null hypothesis of linearity is rejected in favor of a nonlinear Markov-switching model with regime shifts. |

| 9 | To clarify, the estimated economic contraction is the fitted values of MS-AR process, . |

| 10 | Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Economic Research Division. |

| 11 | It is important to mention the impact of the generated regressor on asymptotic variance. |

| 12 | Table A4 in the appendix guides statistical model selection, especially containing the results of the Hausman test to verify the existence of the heterogeneous effect. |

| 13 | The statistical model is Equation (8). |

| 14 | |

| 15 | In standard literature, EZ parameters, and , are interpreted as risk aversion and elasticity of intertemporal substitution, respectively. However, this interpretation may not be strictly satisfied when differs from the reciprocal (Garcia et al. (2006), and Hansen et al. (2007)). The Euler equation and the consequent calibration exercise, as expected, highlight that the model is based on a special case of power utility with a bit of parameter relaxation (consistent with Barro (2009)). |

| 16 | In cases of interest, the results based on the first ten principal components can be provided. |

| 17 | |

| 18 | All values are reported in percentage terms. |

| 19 | The P/E ratio can present insights into investors’ expectations for a firm’s future growth prospects. A high P/E ratio implies that investors anticipate strong earnings growth in the future, which increases the risk of possible missed expectations. |

| 20 | The standard definition of Cash Conversion Cycle = DIO + DSO − DPO. Increasing DPO, decreasing DSO, or decreasing DIO results in quicker conversion. |

| 21 | The ideal target ratio may vary by industry. |

References

- Baayen, R., Davidson, D., & Bates, D. (2008). Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. Journal of Memory and Language, 59(4), 390–412, (Special Issue: Emerging Data Analysis). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, R., Kiku, D., & Yaron, A. (2012). An Empirical Evaluation of the Long-Run Risks Model for Asset Prices. Critical Finance Review, 1(1), 183–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, R. J. (2006). Rare Disasters and Asset Markets in the Twentieth Century. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(3), 823–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, R. J. (2009). Rare Disasters, Asset Prices, and Welfare Costs. American Economic Review, 99(1), 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretscher, L., Hsu, A., Simasek, P., Tamoni, A., & Roussanov, N. (2020). COVID-19 and the Cross-Section of Equity Returns: Impact and Transmission. The Review of Asset Pricing Studies, 10(4), 705–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillinger, D. R. (2001). Time series. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockwell, P. J., & Davis, R. A. (1991). Time series: Theory and methods. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Burger, A. E. (1969). A historical analysis of the credit crunch of 1966. Review, 51, 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J. Y. (1993). Intertemporal Asset Pricing without Consumption Data. American Economic Review, 83(3), 487–512. [Google Scholar]

- Chib, S. (1998). Estimation and comparison of multiple change-point models. Journal of Econometrics, 86(2), 221–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J., Greenwald, D. L., & Ludvigson, S. C. (2020). What explains the COVID-19 stock market? (NBER Working Papers No. 27784). National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daadmehr, E. (2024). Workplace Sustainability or Financial Resilience? Composite-Financial Resilience Index. Risk Management, 26, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daadmehr, E. (2025). COVID-19 Intensity, Resilience, and Expected Returns. Risks, 13(3), 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempster, A. P., Laird, N. M., & Rubin, D. B. (2018). Maximum Likelihood from Incomplete Data Via the EM Algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 39(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W., Levine, R., Lin, C., & Xie, W. (2021). Corporate immunity to the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Financial Economics, 141(2), 802–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dingel, J., & Neiman, B. (2020). How many jobs can be done at home? Journal of Public Economics, 189(C), 104–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, L. G., & Zin, S. E. (1989). Substitution, Risk Aversion, and the Temporal Behavior of Consumption and Asset Returns: A Theoretical Framework. Econometrica, 57(4), 937–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahlenbrach, R., Rageth, K., & Stulz, R. M. (2020). How Valuable Is Financial Flexibility when Revenue Stops? Evidence from the COVID-19 Crisis. The Review of Financial Studies, 34(11), 5474–5521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabaix, X. (2012). Variable Rare Disasters: An Exactly Solved Framework for Ten Puzzles in Macro-Finance. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127(2), 645–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R., Renault, É., & Semenov, A. (2006). Disentangling risk aversion and intertemporal substitution through a reference level. Finance Research Letters, 3(3), 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gelman, A. (2005). Analysis of Variance: Why It Is More Important than Ever. The Annals of Statistics, 33(1), 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, M., Kilic, M., & Seo, S. B. (2022). Learning, slowly unfolding disasters, and asset prices. Journal of Financial Economics, 143(1), 527–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glossner, S., Matos, P. P., Ramelli, S., & Wagner, A. F. (2024). Do institutional investors stabilize equity markets in crisis periods? Evidence from COVID-19. (Swiss Finance Institute Research Paper No. 20-56. Forthcoming at Management Science). European Corporate Governance Institute. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourio, F. (2012). Disaster Risk and Business Cycles. American Economic Review, 102(6), 2734–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J. D. (1990). Analysis of time series subject to changes in regime. Journal of Econometrics, 45(1), 39–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, L. P., Heaton, J., Lee, J., & Roussanov, N. (2007). Intertemporal Substitution and Risk Aversion. In J. Heckman, & E. Leamer (Eds.), Handbook of Econometrics (Vol. 6, chap. 61). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, C. R. (1982). Analysis of covariance in the mixed model: Higher-level, nonhomogeneous, and random regressions. Biometrics, 38(3), 623–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensvik, L., Barbanchon, T. L., & Rathelot, R. (2020). Which jobs are done from home? Evidence from the american time use survey. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3574551 (accessed on 13 April 2020).

- Houmes, R., & Chira, I. (2015). The effect of ownership structure on the price earnings ratio—returns anomaly. International Review of Financial Analysis, 37, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoxworth, D. H., Miller, G. H., & Mitchell, K. (1983). The U.S. economy and monetary policy in 1983. Economic Review, 68, 3–21. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/a/fip/fedker/y1983idecp3-21nv.68no.10.html (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Hörmann, S., Kidziński, ń., & Hallin, M. (2015). Dynamic functional principal components. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B, 77(2), 319–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jitmaneeroj, B. (2017). The impact of dividend policy on price-earnings ratio. Review of Accounting and Finance, 16(1), 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordà, Ò., Singh, S. R., & Taylor, A. M. (2022). Longer-Run Economic Consequences of Pandemics. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 104(1), 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, M., & Pető, R. (2020). Business disruptions from social distancing. PLoS ONE, 15(9), e0239113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krolzig, H. (1997). Markov switching vector autoregressions modelling: Statistical inference and application to business cycle analysis. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Landier, A., & Thesmar, D. (2020). Earnings Expectations during the COVID-19 Crisis. The Review of Asset Pricing Studies, 10, 598–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, I. A., & Narciso, A. (2020, July 29–31). Does Earnings Management Influence Dividend Policies? An Approach with Unlisted Firms. Xx usp international conference in accounting, Sao Paolo, Brazil. Available online: https://congressousp.fipecafi.org/anais/20UspInternational/ArtigosDownload/2352.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Lustig, H., Nieuwerburgh, S. V., & Verdelhan, A. (2013). The Wealth-Consumption Ratio. The Review of Asset Pricing Studies, 3(1), 38–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, R., & Prescott, E. C. (1985). The equity premium: A puzzle. Journal of Monetary Economics, 15(2), 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, M., Wagner, C., & Zechner, J. (2023). Disaster resilience and asset prices. Journal of Financial Economics, 150, 103712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, M., & Zechner, J. (2022). COVID-19 and Corporate Finance. The Review of Corporate Finance Studies, 11(4), 849–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomino, F., Paolillo, S., Perez-Orive, A., & Sanz-Maldonado, G. (2019). The information in interest coverage ratios of the us nonfinancial corporate sector (Economic Research). FEDS Note. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettenuzzo, D., Sabbatucci, R., & Timmermann, A. (2023). Payout suspensions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Economics Letters, 224, 111024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramelli, S., & Wagner, A. F. (2020). Feverish Stock Price Reactions to COVID-19. The Review of Corporate Finance Studies, 9(3), 622–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, W. P. (2008). Intertemporal Cost Allocation and Investment Decisions. Journal of Political Economy, 116(5), 931–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staehle, M., & Lampenius, N. (2013). What is driving the price-to-earnings ratio: The effect of conservative accounting and growth. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2239208 (accessed on 26 April 2025).

- Stulz, R. M. (2025). Risk, the Limits of Financial Risk Management, and Corporate Resilience. Annual Review of Financial Economics, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supel, T. M. (1978). The U.S. Economy in 1977 and 1978. Quarterly Review, 2(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachter, J. A. (2013). Can Time-Varying Risk of Rare Disasters Explain Aggregate Stock Market Volatility? The Journal of Finance, 68(3), 987–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachter, J. A., & Zhu, Y. (2024). Learning with rare disasters. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3407397 (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Weil, P. (1989). The equity premium puzzle and the risk-free rate puzzle. Journal of Monetary Economics, 24(3), 401–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitzman, M. L. (2005). A unified Bayesian theory of equity ‘puzzles’. Available online: https://conference.nber.org/confer/2005/mes05/weitzman.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2025).

| Nonlinear Markov Switching | Coefficients (StDev) | t-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept: | 100.69 (0.013) | 592.00 *** |

| AR-1: (Disaster state) | 1.03 (0.01) | 65.40 *** |

| AR-1: (Non-Disaster state) | 0.97 (0.003) | 172.00 *** |

| p(Disaster|Disaster) | 0.91 (0.02) | 63.20 *** |

| p(Disaster|Non-Disaster) | 0.02 (0.005) | 4.51 *** |

| log-likelihood statistics | 431.80 | |

| LRT statistics | 1102.7 ** |

| Transition Probability | Disaster State at Time t | Non-Disaster State at Time t |

|---|---|---|

| Disaster state at time t + 1 | 0.91 | 0.02 |

| Non-Disaster state at time t + 1 | 0.08 | 0.97 |

| Dependent Variable: Dividend Growth | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Industries | Industry Sector (NAICS Code) | |||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| 0.0007 ** (0.0002) | 0.0027 (0.0014) | 0.0041 *** (0.0003) | −0.0026 ** (0.0008) | −0.0029 *** (0.0005) | 0.0113 *** (0.0025) | |

| −0.0029 * (0.0004) | 0.0066 ** (0.0021) | −0.0045 *** (0.0005) | 0.0052 *** (0.0011) | −0.0022 *** (0.0006) | −0.0082 * (0.0032) | |

| −0.0025 * (0.0005) | 0.0010 (0.0028) | −0.0013 (0.0007) | 0.0025 (0.0015) | −0.0050 *** (0.0008) | 0.0132 ** (0.0042) | |

| −0.000007 *** (0.0022) | −0.0092 * (0.0037) | −0.0014 (0.0008) | −0.0029 (0.0020) | 0.0030 ** (0.0011) | 0.0026 (0.0058) | |

| 0.00001 (0.0008) | −0.0060 (0.0045) | 0.0002 (0.0011) | 0.0055 * (0.0025) | −0.00007 (0.0013) | 0.0310 *** (0.0069) | |

| −2.3149 *** (0.0889) | −0.7308 (0.4882) | −1.8041 *** (0.1191) | −2.4705 *** (0.2832) | −3.2298 *** (0.1399) | −3.2044 ** (0.0085) | |

| Average of workplace resilience (heterogeneous effect) | 10.3690 *** (0.4622) | 2.6394 *** (0.5561) | 8.0623 *** (0.4327) | 11.2225 *** (0.5193) | 14.5646 *** (0.3182) | 14.0970 *** (0.6553) |

| F-statistics | 127.48 *** | 4.013 * | 79.816 *** | 19.303 *** | 105.565 *** | 11.4737 *** |

| K | Workplace Resilience | Minimum | 1st Qu. | Median | Mean | 3rd Qu. | Maximum | Group Comparison Test p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | High | 9.88 | 10.21 | 10.29 | 10.33 | 10.52 | 10.52 | 0.00 *** |

| Low | 9.35 | 9.16 | 10.41 | 10.38 | 10.69 | 10.51 | ||

| 3 | High | 10.05 | 10.05 | 10.22 | 10.19 | 10.22 | 10.33 | 0.00 *** |

| Low | 9.35 | 10.15 | 10.41 | 10.36 | 10.72 | 11.41 | ||

| 4 | High | 10.05 | 10.05 | 10.21 | 10.17 | 10.22 | 10.29 | 0.00 *** |

| Low | 9.35 | 10.16 | 10.44 | 10.34 | 10.72 | 11.41 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daadmehr, E. Resilience and Asset Pricing in COVID-19 Disaster. Economies 2025, 13, 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13050123

Daadmehr E. Resilience and Asset Pricing in COVID-19 Disaster. Economies. 2025; 13(5):123. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13050123

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaadmehr, Elham. 2025. "Resilience and Asset Pricing in COVID-19 Disaster" Economies 13, no. 5: 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13050123

APA StyleDaadmehr, E. (2025). Resilience and Asset Pricing in COVID-19 Disaster. Economies, 13(5), 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13050123