1. Introduction

Peanuts (

Arachis hypogaea L.), commonly known as groundnuts, are an annual crop belonging to the Leguminosae family and in Kenya, are mainly grown in the arid savannah zones in the west of the country (

Ministry of Agriculture (MoA), 2009). Peanut farming is an important livelihood activity in many rural communities around the world. Peanuts are consumed as peanut butter, peanut oil, salted and roasted, and consumed as a confectionery snack, or used in sweets. They are also boiled and consumed, either in the shell or unshelled (

Bioversity International, 2017). Peanuts grow well in the arid and semi-arid tropics, require little input, and integrate well into rain-fed crop rotations and intercrop systems.

Many different types of peanuts are grown throughout Africa. These differ greatly in crucial properties such as the number of seeds per pod, the color of the seed coat, the size of the seed, the time to maturity of the crop, the dormancy of the seed after harvest, the oil content, and the taste (

International Fund for Agricultural Development, 2009).

Women are actively involved in planting, harvesting, processing, and selling peanuts, and peanuts are widely grown for both personal and commercial purposes (

Daudi et al., 2018). Peanuts are a high-value, easily marketable, and nutritious food that are utilized as an ingredient in many traditional recipes and snacks, as a primary source of calories, fat, protein, vitamins, and minerals (

WHO, 2002). Peanuts are an important crop for Kenya’s food security. According to food availability data from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) database for 2021, peanuts contribute significantly to food security in many parts of the world (

FAO et al., 2021). Embracing new agricultural technologies in Kenya could help peanut farmers improve productivity, household income, and nutrition. Despite this, the peanut value chain is relatively neglected in Kenya (

FAO et al., 2021).

Under the First Medium-Term Plan (MTP1), the Kenyan Government Vision 2030 identified the need for investment to assist farmers in transitioning from subsistence agriculture to increasingly appealing commercial farming (

Ministry of Agriculture (MoA), 2009). This plan prioritized agricultural output, particularly in rural regions, in order to alleviate poverty among smallholder farmers while also connecting local farms to available markets through farmer education and extension services. Peanut-growing regions in Nyanza Kenya, such as Homa-Bay, Kisumu, Migori, and Siaya Counties, have listed peanuts as their priority crop for advancement in their agricultural strategic plans (CIDP, 2018–2022).

Over time, national governments and international agencies such as the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the United Kingdom’s Aid Direct (UKAID) proposed that improving agricultural value chain efficiency, increasing access to diverse markets, and providing extension services to encourage farmers to embrace modern production technologies were all cost-effective ways to achieve poverty reduction and economic empowerment for smallholder farmers (

United States Agency for International Development (USAID), 2018).

When compared to global peanut producers such as India, the United States, and Argentina, Kenya faces substantial gaps in its peanut value chain. India is the world’s largest producer of peanuts, with a well-established and integrated value chain that includes both smallholder and large-scale commercial farming. India has made significant strides in improving productivity through government support programs, including subsidies for fertilizers and seeds, as well as through research on pest-resistant varieties. The peanut industry in India has become highly mechanized in certain regions, allowing for higher yields and better processing capabilities (

Indian Council of Agricultural Research, 2021).

The United States peanut industry is characterized by advanced technology, significant government support, and a well-organized processing sector. The U.S. is a leader in value-added peanut products, such as peanut butter and oil. Mechanization in farming and harvesting, alongside research in pest management and soil fertility, has significantly boosted productivity. The U.S. government provides farmers with price support programs, which help stabilize the peanut market and ensure consistent production (

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), 2020). The United States also has a sophisticated infrastructure for storage, processing, and distribution, which allows for high-quality exports.

Argentina, a major peanut exporter, has a highly developed processing sector, particularly for export markets like Europe and the U.S. The country benefits from efficient processing facilities and a favorable climate for peanut production. Like Kenya, Argentina has a substantial number of smallholder farmers, but it has succeeded in increasing productivity and exports through better infrastructure, access to improved seeds, and government research programs. The Argentine government also supports peanut growers with subsidies and extension services (

Argentine Ministry of Agriculture, 2022).

The key challenges confronting Kenyan agriculture and highlighted by the MTP1 include the difficulties associated with rain-fed agriculture, the low level of mechanization in production and processing, high post-harvest losses due to poor post-harvest management, low and ineffective agricultural finance, poor extension services due to institutional and structural inefficiencies, and insufficient markets and processing facilities. Identifying the specific challenges in the peanut value chain provides an opportunity to identify upgrading opportunities for strategic investments in the peanut value chain to leverage existing strengths and opportunities. This could potentially increase efficiency and increase income for all actors in the peanut value chain. This would also create employment opportunities, particularly in the rural areas where the peanuts are produced.

It is in light of these issues that we analyze the performance of the peanut value chain in the main peanut production areas of Kenya. More specifically, we identify the constraints and opportunities at each node of the value chain, analyze the financial and market values across the entire chain. We identify the financial and market constraints within Kenya’s peanut value chain, and determine how socio-economic factors may influence the adoption of improved peanut farming practices. Based on this, we then propose policy recommendations for the development of a sustainable and improved peanut value chain in Kenya.

In Kenya, peanut production is currently not considered a commercially viable farming activity and there are no structured marketing channels for peanuts in Kenya. Peanut production data is poorly documented and reported by the Ministry of Agriculture in its annual statistical reports. The data in

Figure 1, show that production was highest in 2013 at 94,072 t with an average yield of 5.4 tha

−1 over a harvested area of 17,311 ha. Since then, average yields and thus overall production have greatly decreased, whilst the harvested area has declined, although this has been less acute. The lowest harvested area of 5725 ha was recorded for 2016, with a production of 10,687 tat an average yield of 1.9 tha

−1. Since 2016, the relatively low average yields, production, and harvested have persisted, suggesting that a plateau in yield and production has been reached (

Food and Agriculture Organization, 2022).

However, local demand for peanuts has been on the rise resulting in traders importing peanuts from Italy and India to complement national production (

Food and Agriculture Organization, 2022). According to data from (

Food and Agriculture Organization, 2022), the western Region of Kenya accounts for about 87.4% of 2022 total production, followed by the coastal Region with about 11.3% and 1.3% coming from other regions of the country. As the demand for peanuts has increased whilst production has decreased, a large demand gap has been created. The reason for the decline in production is due to a reduction in average yields as well as the area of land under peanuts resulting from farmers shifting to other crops such as maize (

Cervini et al., 2022). The increased demand is influenced by population growth, cultural and culinary preferences, nutritional requirements, industrial use, and export market (

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS), 2021).

The Kenyan government’s MTP1aims to promote good agricultural practices (GAPs) in agricultural production and facilitate market access through collaboration with local authorities and value chain participants in the public and private sectors. Under the government’s Food and Agriculture Sector Development Policy (FASDEP), the MTP1 identifies peanuts as one of the priority crops in the western part of the country (

Ministry of Agriculture (MoA), 2017). According to the MTP1, peanuts are unique among the country’s traditional staple crops in that they have the highest commercialization index of 42%. While the MTP1 emphasizes the need to increase industrial processing of the country’s traditional commercialized smallholder crops, it pays little attention to peanut production and processing (

Agriculture and Food Authority (AFA), 2017).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

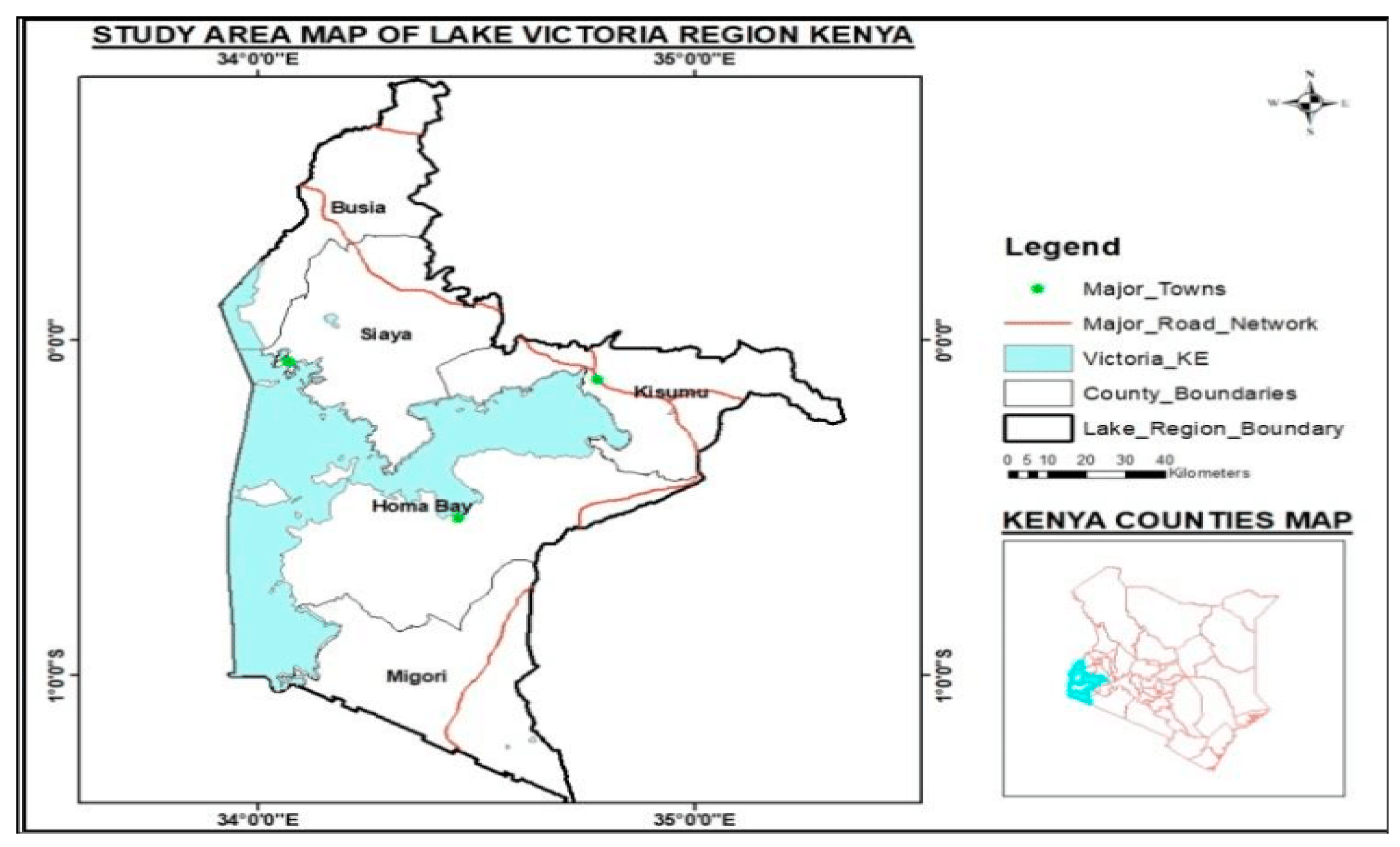

This research was conducted in the Nyakach and Karachuonyo sub-county areas of Kenya, which are regarded to be within the Lake Victoria Basin (

Figure 2). The Lake Victoria Basin has savannah climate characteristics that are suitable for peanut production. It has altitudinal variations ranging from 1131 m to 4000 m and temperatures ranging from 64 °F to 88 °F (20 to 30 °C). Because of the location’s proximity to Lake Victoria, relative humidity is fairly high in both counties (

Kenya Metropolitan Department, 2024). The two study sites, Karachuonyo and Nyakach sub-counties, are located within Homabay and Kisumu counties. The Lake Basin region is one of the food baskets of Kenya with a long history of agricultural activity among local communities. Many communities within the two sub-counties comprise farming households with similar cultural beliefs, values, and agricultural systems, and are actively engaged in food crop production (

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS), 2019;

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS), 2021). The inhabitants of Karachuonyo live in semi-arid climatic conditions favoring crops such as peanuts, cowpeas, yams, soya, sorghum, cassava, millet, and simsim, which are currently neglected and underutilized, with underdeveloped value chains. Karachuonyo also imports such crops from neighboring counties like Kisii, Nyamira, and Migori to the south and Siaya County to the north.

Both sites have similar rainfall patterns, with a major long rainy season between April and June and a short rainy season between September and December. Due to large agricultural markets, the two study areas are also heavily influenced by and affected by market pressures. At the same time, the area is entirely dependent on rain-fed agriculture, necessitating the need for drought-resistant crop species in the face of climate change.

2.2. Value Chain Analysis Framework

The value chain analysis frame-work used in this study consists of several steps that must be completed sequentially and was developed during the EWA-BELT project. The framework drew on the work of

Porter (

1985), Department for International Development (

DFID, 2008),

Usman (

2016), and

Rashid (

2019) and is comprised of four major steps:

Step 1: This step involves mapping out the value chain to identify the different nodes of the chain and identifies the actors at the various nodes. This is accomplished through Focus Group Discussion (FGD) sessions with a chosen group of value chain actors.

Step 2: This step involves identifying the constraints and opportunities at the various nodes of the value chain. SWOT analysis is carried out at the different nodes of the chain to identify the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats at each node. This allows recommendations and solutions to be proposed that can mitigate the weaknesses and threats to the value chain, as well as strengths and opportunities to be identified for boosting the value chain.

Step 3: This step entails gathering market data and analyzing the market and financial values, identifying support services, and product flow and distribution within the value chain. Market data is collected at all the nodes to facilitate the estimation of net margins, market margins, benefit-cost ratios, and return on investment at the various notes. This helps the distribution of market and financial values across the chain to be calculated. This then supports the development of strategies to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the chain and in particular, helps ensure that issues of equity, which is essential for the sustainability of any value chain, can be examined.

Step 4: This step includes the identification and promotion of recommended options to boost the value chain. This entails making comprehensive recommendations on what should be implemented across all the nodes of the value chain to ensure equity, effectiveness, efficiency, and sustainability across the value chain.

2.3. Research Design and Primary Data Collection

A mixed-methods strategy was applied in this study. This has been referred to as a “qual quant” approach by

Gerring (

2007) and an “integrated research paradigm” by

Saunders et al. (

2007). This approach incorporates multiple schools of philosophy, such as positivism, interpretivism, and realism. According to

Saunders et al. (

2007), the mixed-method approach is typically utilized when researchers want to obtain a more comprehensive and in-depth understanding of a research subject.

This strategy incorporates the collection of both qualitative and quantitative data from study participants and the use of a wide range of analytical tools, including both econometric and non-econometric analysis. The study employed qualitative approaches such as focus group discussions, key informant interviews, life history, and field observations. A survey instrument was also developed and employed to help collect quantitative and qualitative data. Secondary data were obtained from sources such as journal articles, newsletters, yearly reports, presentations at conferences, and annual statistics reports.

Value Chain Actor Survey: A survey questionnaire was developed and administered to randomly select peanut value chain actors (producers, traders, and processors) in the study area. Respondents were met at their homes and their consent was sought before their participation in the study.

Focus Group Discussions: Eight focus group discussions were held in accordance with the research objectives, using a pre-determined checklist of questions as a guide. Focus group discussions were considered to be suitable for the study because they provide a platform for dynamic interaction between researchers and participants, which often results in the collection of valuable information. Each of the two study sites had four focus group sessions. Each focus group consisted of 10 respondents, primarily value chain actors over the age of twenty-five, with over five years of experience in the peanut value chain were selected to participate. In each study area, the focus group discussion was carried out among all the value chain actors including the first focus group discussion with ten farmers, the second one with10sellers, the third one with 10 small-scale processors, and the fourth focus group discussion was carried out with 10 members of the farmer’s cooperatives.

Key Informant Interviews: These were used to acquire an in-depth understanding of the history of the peanut value chain in the studied locations. Ten key informants were interviewed at various levels of the value chain, with people believed to have extensive knowledge of the peanut value chain. The informants included traders (3), processors (4), and agricultural extension officers (3) from the Ministry of Agriculture and from the study area. The key informants were chosen based on their education and understanding of agricultural activities in the research area.

SWOT analysis: The SWOT analysis was applied to all nodes of the peanut value chain using the following steps:

Data Collection: Information was gathered through focus group discussions, key informant interviews, and surveys of value chain actors.

Categorization: Responses were categorized into four quadrants: e.g., Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats after which the SWOT analyses were performed individually for each node highlighting node-specific strengths and weaknesses.

The financial indicators were calculated using the net margin (Equation (1)) and return on investment(ROI) (Equation (2)) formulas described below:

Field observations: The researcher attended certain local events and visited local markets, as well as other locations of interest, to witness various activities and practices in order to become better acquainted with and comprehend the people’s way of life and support the interpretation of the qualitative data collected. The observational procedure, which comprised a form prepared to record information during the observation period, was used to conduct the observations.

Sampling technique and sample size: A multi-stage sampling technique was used in this study. The research regions were chosen based on their long history of peanut cultivation and the suitability of their climatic for peanut production. Farmers, traders, aggregators, and processors along the value chain were randomly selected and interviewed. The total sample size for this study was 120, which included 60 farmers and 20 aggregators, traders, and processors from the from the two study locations (

Table 1).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Demographic Information of the Participants

The results in

Table 2 indicate that out of the 120 farmers sampled, the majority of them were women (68%). This result indicates there were more female peanut farmers than their male counterparts. The findings are similar to the work of

Wanyama et al. (

2013a) on peanut farmers in Rongo and Ndhiwa. The majority of distributors in the value chain were female (70%). A similar trend was observed among aggregators, traders, and processors with female participation at 70%, 60%, and 60% respectively. These results suggest that the peanut industry is female-dominated across all nodes of the value chain. About 70% of all value chain actors have at least primary education as shown in

Table 2 below.

3.2. SWOT Analysis of the Peanut Value Chain

3.2.1. The Input Supply Node

The peanut value chain begins with input suppliers who supply inputs such as seeds, agrochemicals, and pesticides to producers. The study found that 73% of peanut producers get their seeds from saved seeds, which aligns with findings from

Owusu-Adjei et al. (

2017) in Ghana, who found that 59% of farmers get their peanut seeds from the previous year’s production. Only 20% of farmers buy seed from input suppliers, and 7% receive seed as a gift from family and friends. Peanut farmers do not use fertilizer in their peanut cultivation. The strength identified is the availability of technical know-how. The weakness is the low awareness of improved varieties. The identified opportunities include high demand for certified seed and a favorable policy environment, and threats are short shelf life, high cost of transportation, and low market price at harvest as shown in

Table 3 below. This low adoption of improved varieties and fertilizer is a major contributor to the low yields and low production levels reported for peanut production in Kenya.

3.2.2. The Production Node

Peanut production occurs primarily in rural areas and is controlled by smallholder farmers, the majority of whom are female (68%). Despite being dominated by females, there is still significant male engagement when compared to other crops such as sorghum and finger millet (

Wanyama et al., 2013b). Land preparation, sowing, weed control, pest and disease control, harvesting, and post-harvest management are some of the production activities. In certain cases, peanut farmers engage workers to perform tasks such as weeding and harvesting peanuts. However, in most cases, in addition to contracted labor, family labor is used to reduce labor costs. For peanut production, 5% utilize only hired labor, 17% use mixed labor (hired and family), and the remaining 78% use only family labor.

Peanut production in this area is heavily reliant on rain-fed production, with two rainy seasons, the main season from April to August and the short season from September to October. Farm sizes are typically small, averaging 0.2 ha. This is supported by findings from

Wanyama et al. (

2013b) which indicate that peanuts are predominantly grown on a modest scale, with farm sizes ranging from 0.5 ha to 1.5 ha. Depending on the weather, harvested nuts are sun-dried for two weeks. Approximately 56% of the farmers who participated in the survey sell their peanuts unshelled, whereas 44% sell them shelled. Unshelled peanuts typically have lower prices than shelled peanuts. Farmers who used both local and improved seed types had the same area under each on average. The average area under peanuts per season was 0.5 ha. According to the findings, the yield of farmers who used improved varieties was about 70% greater than the yields of farmers who used the unimproved local seed varieties. Farmers grew peanuts primarily for personal consumption. The surplus was sold at various prices through various market channels. According to the Kenya Agriculture and Food Authority (

Agriculture and Food Authority (AFA), 2017), the yields ranged between 2–3 tha

−1 across all the production zones and the farm gate prices ranged between USD 2.67 kg

−1 to USD 3.87 kg

−1. The formal market prices were about 40% higher than the open market price.

The strengths at the producer node include access to improved seeds and high-profit margins. The weakness identified is the inability of producers to grade and ensure standardization. The opportunities for peanut producers include high market demand, low input requirements, and availability of improved varieties. The threats include pests and diseases, short shelf life of peanuts, low awareness of the nutritional benefits, poor road network, and seasonal glut presenting an opportunity for the node to be enhanced when they are addressed (

Saha & Sarker, 2019). The results are shown in

Table 4 below.

3.2.3. The Aggregator Node

Aggregators (middlemen) act as a conduit between farmers and traders. These agents are usually farmers or members of the farming community. They typically guide purchasers who are unfamiliar with the whereabouts of various farmers. The main services they provide in the value chain are production transportation and market information supply. They occasionally buy farmers’ products and store them in town centers so that buyers (traders) from urban areas can conveniently get them. They are not always brokering because they follow the orders of urban wholesaler buyers and producers. Most of the time, urban retailers advance their money to buy produce from farmers.

The SWOT analyses (

Table 5) identified aggregators’ easy access to farmers as their strength, whilst farmers’ interest in selling some of their produce to them, and competitive prices offered were seen as opportunities. The threats identified were that many aggregators in the system resulting in stiff competition, harvesting regimes not the same, and low-quality peanuts.

3.2.4. The Trader Node

Women dominate the peanut trader node, which encompasses aggregation, wholesale, and retail services for both raw and processed peanuts. There are no trade associations and traders work individually. The market determines peanut pricing through laissez-faire methods. This indicates that there is no standard market price and that each market participant has the freedom to set his or her own price. The market allows for unrestricted entry and exit. Raw peanuts from production locations are sold both locally and internationally. These are traded at the farm gate, a market in the local community or an adjacent community, or in a wholesale market within the county, or sometimes in a wholesale market beyond the county. Distributors, in addition to acting as market intermediaries, buy peanuts directly from farmers or markets in production areas and supply them to customers. Aggregators in rural communities buy from farmers and sell to wholesalers. Occasionally, a lot of distributors, mainly wholesalers, travel from one village to another or even across the country to Uganda and Tanzania to purchase peanuts. This is mostly done during the off-season when local supply is low.

The majority of aggregators finance their transactions using their own resources. They can also obtain financial advances from wholesalers, who play a major role in informal rural finance. According to the Kenya Agriculture and Food Authority (AFA) report (2017), some Nairobi wholesalers do not always travel to producing regions to buy peanuts, but instead, transfer money to their aggregators to aggregate for them. The aggregators, in turn, do all of the purchases and convey the peanuts to the wholesalers.

According to

Table 6 SWOT analyses, the weakness identified at this node is the poor access to market information, and threats include short shelf life, poor financial support, and a poor transport system. The strengths include access to readily available markets and access to improved varieties. The opportunities include availability of preferred varieties and demand from local and international markets. Improved access to market information, good roads, and access to financial services are also needed to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the node.

Traders are mostly specialized in the shelled peanut trade. The majority of traders were found in metropolitan areas. This is due to better access to supplies and the presence of a large number of consumers and retailers. The vast majority of them were sole traders. Although the crop is harvested twice a year, the bulk of traders (88.4%) trade in peanuts all year long because peanuts can be stored throughout the year and there is demand throughout the year. Most of the traders trade in multiple commodities. Peak peanut availability was observed in April, followed by January, August, and February, which is the period when peanuts are harvested. During the peak of the season, the most common types of peanut are Red Valencia and Nyahomabay, which were sold both unshelled and shelled in local markets. According to the wholesalers interviewed, the off-peak months for trading in peanuts are September, October, and November, which is actually during the second planting season. However, during this period, most of the products harvested in the first season would have been sold or reserved by farmers for their own consumption, resulting in low supply to the market.

Peanuts are purchased by traders from a variety of sources. According to the findings, most traders obtained their peanuts directly from small-scale farmers and small-scale aggregators. Large-scale farmers and large-scale aggregators were the least preferred source as indicated in

Table 6. Most frequently, traders said they obtained their peanuts from small-scale farmers (42.1% of the time)and small-scale aggregators (36.9% of the time), and were much less frequent in obtaining their peanuts from large-scale farmers and large-scale aggregators (both 10.5% of the time each). The results are as shown in

Table 7 below.

The majority of traders indicated that their suppliers did not offer them any other services. But credit sales, transportation, storage, and advisory services were some of the services a few traders indicated they received from their suppliers.

3.2.5. The Processor Node

The value chain actors at this node are primarily involved with the processing of peanuts, which includes shelling, milling into flour, peanut butter production, packaging, and selling. Some were involved in the roasting and sale of nuts. The vast majority (96%) stated that they processed peanuts all year round. However, there were months of peak supply and low supply. Processor operations are generally small-scale operations and 60% of the processors interviewed were women. They make peanut butter, roasted peanuts, and other peanut products from peanuts. In rural settings, the majority of processing occurs at the household level.

From the SWOT analysis carried out at this node, it was found that strengths included knowledge of food safety measures and low capital requirement. Opportunities included increasing global demand, existing high demand, diversified product potential, online sales, and the availability of peanuts. However, weaknesses identified included poor access to storage facilities and poor knowledge of new processing techniques. Threats included poor access to financial support, unstable market prices, poor product quality, and possible mycotoxin contamination, poor supply of peanuts, and unfavourable regulations and policies. These can be addressed by increasing access to storage facilities and knowledge of PHL management. There is also the need to work towards reducing processing costs. Government support to deal with threats like unregulated import of cheap substitutes, and the provision of policies to encourage and facilitate standardization and product pricing (

Table 8).

Peanuts were obtained from a variety of sources, including small-scale farmers, small-scale traders, and large-scale traders. Processors most frequently sourced their peanuts from small-scale traders (40% of the time) followed by small-scale farmers (26.7% of the time), aggregators (20% of the time), and large-scale traders (13.3% of the time) (

Table 9). The preference for small-scale traders was because they graded the peanuts before selling them to the next actor in the chain. Only 25% of the processors provided services to the peanut suppliers. The services provided were primarily credit and transportation.

The average cost at which processors purchased unshelled and shelled peanuts throughout the peak and off-peak periods is shown in

Table 10. Red Valencia was purchased for a higher price than Nyahomabay. For both varieties, unshelled peanuts were purchased at a substantially lower price than shelled peanuts, as might be expected.

Purchase prices were also projected to be greater during the lean (off-peak) seasons than during the peak supply period. Because of general scarcity, there is upward pressure on prices as demand exceeds supply.

3.2.6. The Consumer Node

Consumers generally purchased pre-sorted and cleaned peanuts from vendors, most of whom were located in local markets and metropolitan areas. Consumers buy either raw or processed products based on their needs and have access to a diverse choice of shops. According to reports (ref), the Kobala and Kong’ou markets are the largest peanut markets in the study region, receiving the majority of the peanuts produced in the area each day, with over 50 traders. Other markets, like Homabay Town, Kisumu Town, and Katito, receive peanuts from the area as well, although on a smaller scale.

The SWOT analysis (

Table 11) identifies strengths to be an affordable, easy to process product, and the availability of multiple distribution channels. The opportunities include easy access; high product diversity and easy market access as shown in below. The weakness is high storage losses and the threats included high price fluctuations, high mycotoxin contamination, and short shelf life. These present opportunities for the upgrading of the node.

3.3. Quality Attributes Considered by Value ChainActors

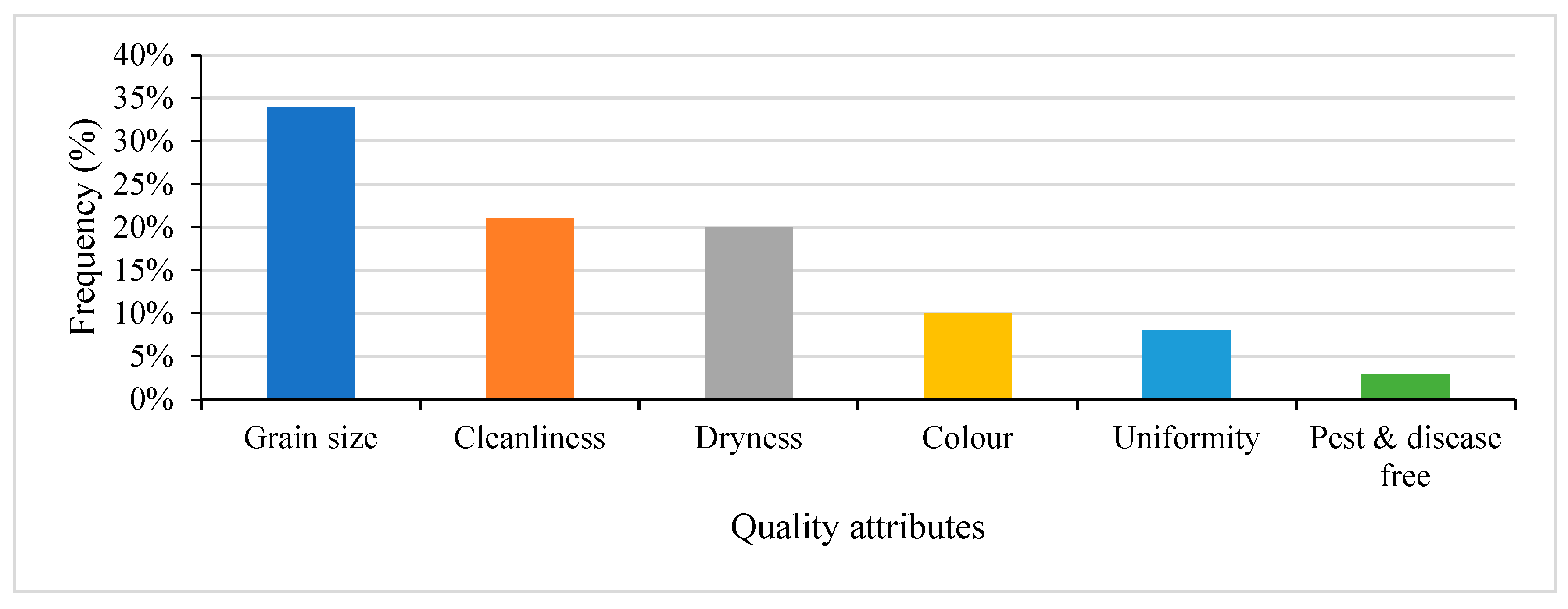

The majority of the value chain actors prefer larger grains (34%) followed by the cleanliness of the grains (21%), dryness of the grain (20%), and grain color (10%) (

Figure 3). Given globalization and export trends, quality is a vital factor that has been emphasized in recent times. Many international and local consumers demand high grain quality. However, maintaining high-quality grain remains a major challenge for value chain actors, even though it is important in attracting premium prices and accessing profitable markets.

3.4. Financial and Market Performance Analyses of Peanut Value Chain

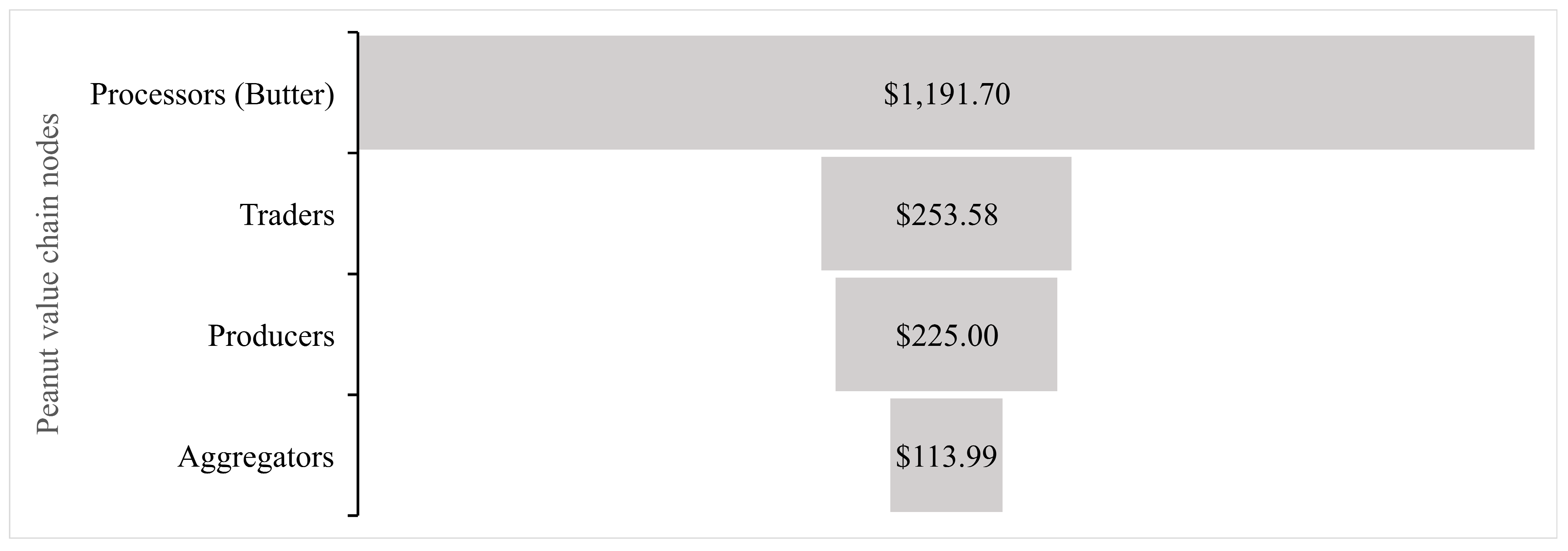

The financial and market performance of the peanut value chain were assessed. The following indicators were analyzed; net margin, benefit-cost ratio, return on investment, and share of market margin. The net margin analysis for one tonne of peanuts transacted across the peanut value chain shows that the processor node provided the highest net margin at

$1191 t

−1 followed by the net margins for traders, producers, and aggregators at

$254 t

−1,

$225 t

−1, and

$114 t

−1 respectively (

Figure 4).

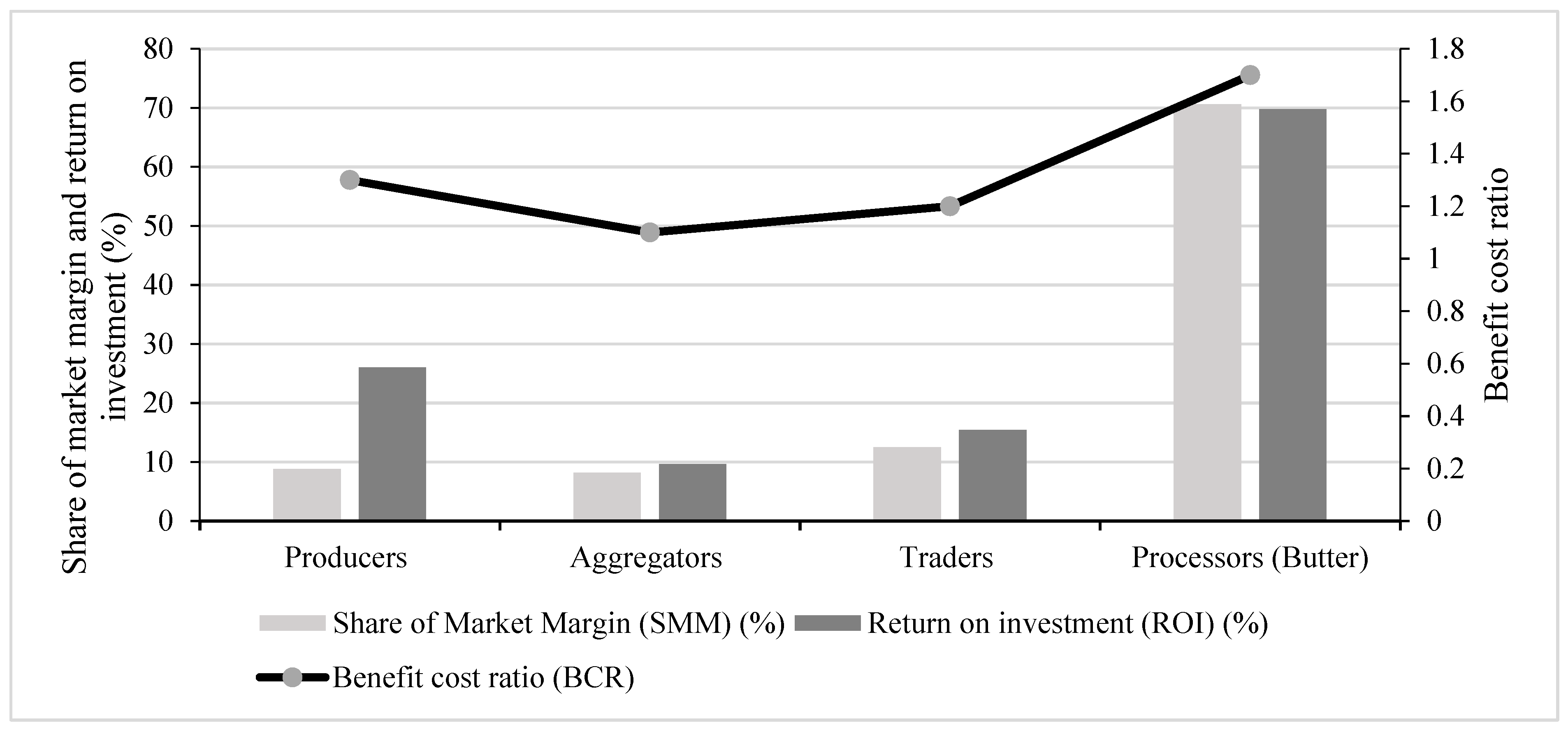

A positive net margin, benefit-cost ratio greater than one, and a positive high return on investment implies that an activity is effective in managing its costs, resulting in its revenue being greater than the cost incurred. The one-tonne analysis across the chain using the benefit-cost ratio, share of market margin, and return on investment indicators shows that the processor node is the most financially viable node followed by producer, trader, and then aggregator nodes (

Figure 5). Thus, all the nodes were found to be profitable and worth the investment. More details of the financial analysis provided in

Appendix A.

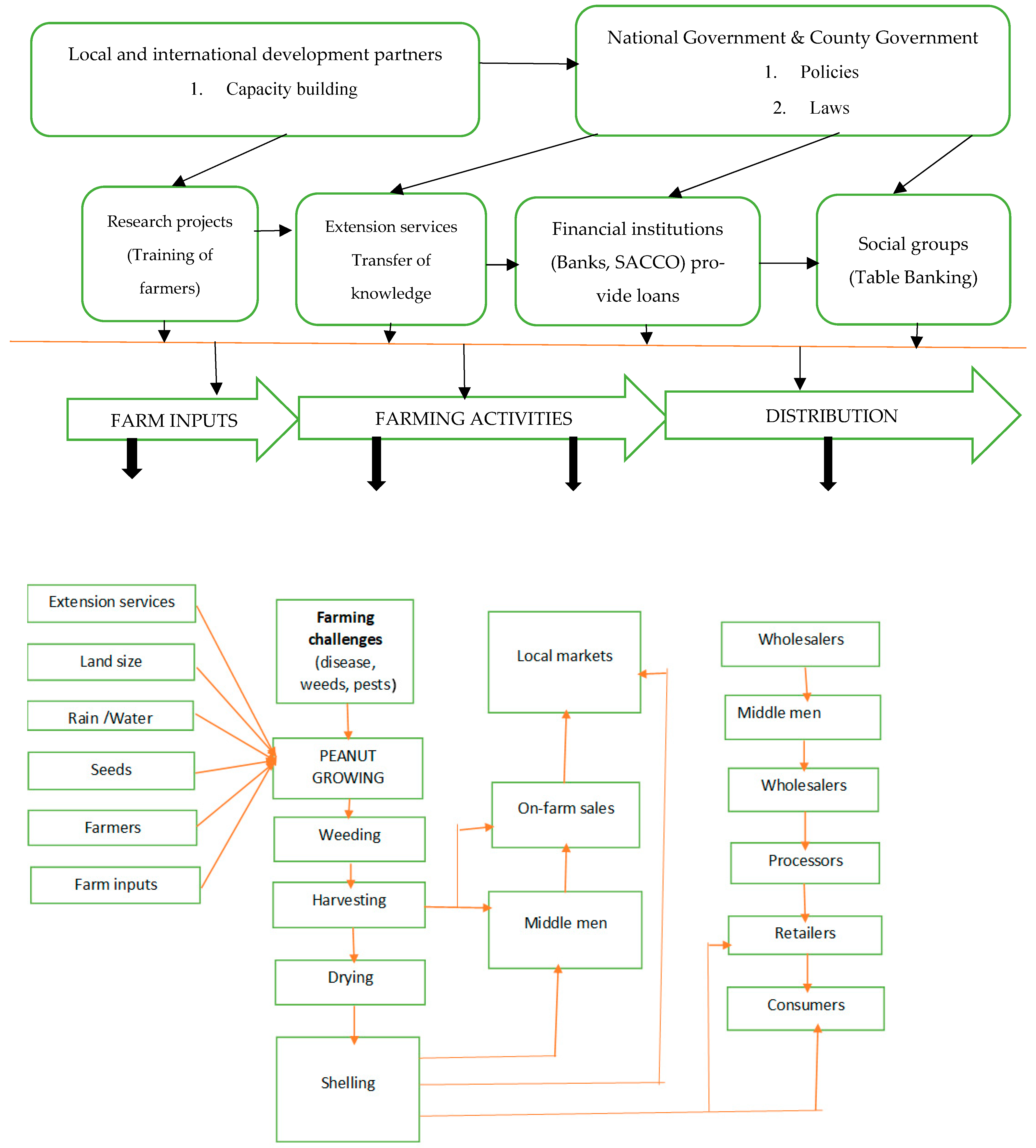

3.5. Peanut Value Chain Map

The current status of the Kenyan peanut value chain is illustrated (

Figure 6), tracing the flow of inputs through production, distribution, and final consumption. The value chain map provides an overview of the peanut value chain, the structure and flow of goods and services, and the linkages between various actors operating within the peanut value chain.

Farm inputs are needed to improve productivity, including high-quality seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, and irrigation systems are essential for successful cultivation. These resources are critical for ensuring healthy plant growth, maximizing yields, and maintaining crop resilience. Proper tools and equipment also play a significant role in enhancing farming efficiency and productivity.

Farming activities include land preparation, planting, crop management, and harvesting. Effective land preparation ensures optimal conditions for planting, while ongoing crop management involves pest control, irrigation, and fertilization to support plant health. Harvesting is a crucial step that involves uprooting the mature plants and preparing the peanuts for further processing.

Distribution requires peanuts to undergo post-harvest handling, including cleaning, sorting, and grading, to maintain quality and includes the aggregator, trader, processor, and consumer nodes of the value chain. Proper storage is essential to prevent spoilage, and efficient transportation ensures timely delivery to processing facilities, markets, and export destinations. Processing converts raw peanuts into value-added products, such as peanut butter and oil. Marketing and sales strategies then facilitate the distribution of these products to consumers through various retail and wholesale channels. Ensuring that peanuts and their products are accessible through diverse outlets and e-commerce platforms helps meet market demand and boosts overall sales.

Optimizing each stage of the value chain—from farm inputs and farming activities to distribution—can enhance efficiency, reduce costs, and increase the value of peanuts. This comprehensive approach supports a well-functioning value chain and benefits all stakeholders involved in the peanut industry.

3.6. Peanut Value Chain Upgrading Opportunities

The peanut value chain boosting opportunities identified across the various nodes of the value chain are presented in

Table 12.

Input supply node: The opportunities at the input supply node include the establishment of more distribution channels to increase the accessibility and affordability of seeds. Seed growers need to do more to sensitize farmers to new and improved varieties and demonstrate to farmers the benefits of using these new varieties. There is a need to facilitate the process of seed certification to ensure seed quality is not compromised. This will increase farmer confidence in buying certified seed.

Production node: Sensitization of farmers to use improved seed will help boost peanut production significantly. Market access is also very critical. Hence contract production and collective marketing are marketing innovations that should be promoted to increase market access and reduce market risk. Capacity-building efforts should be encouraged to enhance producer knowledge of good agronomic practices. Financing peanut production will incentivize farmers to increase their peanut production which will increase supply to the market.

Processor node: Improved storage facilities, such as those with controlled temperature and humidity, can extend the shelf life of peanuts. This ensures a steady supply of raw materials for processors, even during off-harvest seasons. Proper storage minimizes post-harvest losses due to pests, mold, and spoilage. With less wastage, more peanuts are available for processing, leading to higher production levels. Further, better storage facilities help maintains the quality of peanuts, preserving their nutritional content and flavor. High-quality raw materials lead to better end products, enhancing marketability and consumer satisfaction. With the ability to store peanuts longer, processors can stabilize supply, reducing the impact of price fluctuations and ensuring a continuous production process. The processing also assists in creating product diversity such as peanut butter, peanut milk, roasted peanuts, and many other products which enhance value addition attracting good prices.

Consumer node: Consumers should be informed on the nutritional benefits of peanuts, such as it being a good source of protein, healthy fats, and essential nutrients. Further, consumers should be taught new recipes for peanuts, showing their versatility in cooking and baking, whilst ensuring that peanut products meet high quality and safety standards to build consumer trust and loyalty. Innovation and introduction of new peanut-based products such as flavored peanuts, peanut snacks, peanut milk, and health supplements could be supported. At the same time, peanut producers should pursue partnerships with other food brands, restaurants, and chefs to create unique products and dishes featuring peanuts.

Trader node: Boosting opportunities for traders in the peanut value chain involves enhancing market access, supply chain efficiency, financial support, and capacity building. Key strategies include providing real-time market information through digital platforms, improving logistics and storage facilities, and offering affordable credit and trade financing options. Strengthening trader networks and providing training in business management and quality standards are also crucial. Expanding market opportunities through export facilitation and e-commerce platforms, along with supportive policies and risk management tools, can further enhance profitability and reduce risks. These measures empower traders to operate more effectively and capitalize on new opportunities within the peanut value chain.

Research support: Research support in the peanut value chain is critical for enhancing productivity, sustainability, and competitiveness. It includes agricultural research to improve peanut varieties and farming practices, technological development for better equipment and processing methods, and market analysis to understand consumer trends and identify new opportunities. Policy studies could help create a supportive regulatory environment, while sustainability research should focus on environmentally friendly practices and climate resilience. Socio-economic research addresses the well-being of farmers and workers, ensuring inclusive growth within the industry. Together, these research efforts could drive innovation and strengthen the peanut value chain.

Government policy and programs: The Kenyan government should supports the peanut value chain through various policies and programs aimed at enhancing production, processing, and marketing. Key initiatives include providing agricultural support through extension services, subsidies, and financial assistance to boost productivity. The government needs to invest in infrastructure development, such as rural roads and storage facilities, to reduce post-harvest losses and improve market access. Quality control should be forced through standards for aflatoxin levels, and research and development funded to improve peanut varieties and processing technologies. Additionally, the government should promote capacity building, the formation of cooperatives, and the inclusion of peanuts in food security and nutrition programs, ensuring that the peanut industry contributes to economic growth and rural development.

4. Conclusions

The peanut value chain involves a range of key actors, including input suppliers, peanut growers, aggregators, traders, processors, and sellers of processed products. In addition to these primary actors, various supporting entities such as government organizations, non-governmental organizations, banks, and financial institutions provide crucial services to the value chain. Strengthening each segment of the chain, from input supply to processing, is essential for improving the overall efficiency and profitability of peanut production.

To enhance peanut production, it is important to provide farmers with access to high-quality seeds, fertilizers, and pest control methods. Research and development into disease-resistant, high-yielding peanut varieties, along with training programs and extension services, can help farmers adopt best practices and improve productivity. Support for traders and distributors are also vital, as they bridge the gap between producers and processors or consumers. Providing access to market information, financial services, and infrastructure improvements will help streamline transactions, reduce costs, and ensure efficient distribution to both urban and rural markets.

Processors add value to peanuts by transforming them into products like peanut butter, oil, and snacks. To improve competitiveness, investing in modern processing technology, adhering to quality standards, and providing support to processors for meeting international certifications are necessary. Meanwhile, consumer demand drives the entire value chain, and increasing awareness of the nutritional benefits of peanuts can boost consumption. Ensuring the availability of peanut products through diverse retail channels and tailoring products to consumer preferences will further stimulate market growth and improve accessibility.

To strengthen the peanut value chain in Kenya, several key policy recommendations should also be considered. First, enhancing agricultural research and development is crucial. Increasing funding for research institutions and Universities to develop high-yielding, disease-resistant peanut varieties, and sustainable farming practices will address challenges related to climate change and environmental degradation.

Expanding extension services and training programs for farmers, processors, and traders will improve skills in best practices, pest management, and financial management. This is complemented by improving access to finance through affordable credit and tailored insurance products to manage risks such as crop failure and price volatility.

Investing in rural infrastructure, such as roads, storage facilities, and irrigation systems, will reduce post-harvest losses and improve market access. Additionally, developing modern processing facilities will add value to peanuts and create local jobs. Strengthening quality control and enforcing standards will ensure that peanuts meet both domestic and international market requirements, including aflatoxin limits.

Facilitating market access and export opportunities by simplifying trade regulations and supporting compliance with international certifications can enhance the competitiveness of Kenyan peanuts. Supporting the formation of cooperatives and fostering partnerships between farmers, processors, and traders will improve coordination and efficiency within the value chain.

Promoting sustainable practices, such as organic farming and efficient water use, will ensure long-term environmental and economic sustainability. Consumer awareness campaigns and marketing efforts can boost demand for peanuts by highlighting their nutritional benefits and improving product visibility.

Finally, creating incentives for private sector investment in the peanut value chain, through tax breaks or subsidies and facilitating public-private partnerships will drive innovation and infrastructure development. Implementing these recommendations will strengthen the peanut value chain, enhance productivity, and increase the economic contributions of the peanut industry in Kenya.