1. Introduction

Health expenditure represents a key dimension of social welfare investment, directly enhancing population well-being and quality of life. An effective welfare system improves health outcomes, reduces infant and child mortality, and strengthens the labor force by enabling greater participation and productivity, which are fundamental drivers of economic growth. Healthy workers are generally characterized by higher productivity, which facilitates continuous technological advancement and increased output. Within the framework of endogenous growth theory, health spending mitigates disease and the associated labor costs, thereby reinforcing the positive relationship between health, technological progress, and long-term growth.

Beyond its direct economic effects, investment in healthcare and social welfare also contributes to broader economic and social stability. Human capital—together with natural capital—plays a pivotal role in growth, and its formation depends on sustained investments in education, health, and training.

Lucas (

1988) emphasized that public expenditure on education fosters human capital accumulation, which, in turn, promotes economic growth, while

Romer (

1990) highlighted the role of research and development in driving innovation and productivity. Consistent with endogenous growth theory, expenditure on education and health is understood to enhance human capital, stimulate technological progress, and accelerate economic development.

According to the

World Health Organization Global Spending on Health (

2020), global health expenditure has risen to USD 8.3 trillion, equivalent to 10% of global GDP. Notably, private health spending remains disproportionately high in low- and middle-income countries. For this reason, examining the relationship between per capita health expenditure and per capita GDP is particularly important for emerging economies, such as the BRICS countries, as it provides insights into pathways to enhance prosperity and sustain long-term development. GDP per capita remains one of the most widely used indicators of national prosperity and living standards, making its relationship with health investment a critical area of empirical investigation.

The BRICS group, originally comprising Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, has expanded to include Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Indonesia, bringing together major emerging economies to counterbalance Western economic and political dominance. Controlling around 44% of the global crude oil production through key members, BRICS seeks to strengthen cooperation in trade, finance, technology, and development while promoting alternatives to Western-led institutions, such as the IMF and World Bank, including the establishment of the New Development Bank and discussions on a common currency. While China’s economic size and global ambitions, particularly in Africa, give it a dominant role, Russia uses BRICS as part of its strategy to resist Western sanctions. However, the group’s growing heterogeneity—marked by diverging political interests, China–India tensions, and differing strategic goals—raises questions about its cohesion and long-term effectiveness, even as its diversity and shared resources could enhance its global influence.

Health Systems in the BRICS Countries

The accelerating pace of globalization has contributed to the emergence of new markets, particularly economies characterized by sustained long-term growth in gross domestic product (GDP). Among these, the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) have significantly increased their share of global wealth over recent decades, though the pace and balance of their growth trajectories vary considerably. Each member of the BRICS group has undertaken distinct strategies to improve healthcare provision, thereby enhancing population well-being. The expansion of the middle class in these economies has further stimulated demand for advanced medical technologies and pharmaceutical products. However, this progress has also been accompanied by challenges, including unequal access to healthcare among disadvantaged populations, limited diffusion of cutting-edge treatments, and modest innovation rates relative to the substantial investments made in medical research. According to the Global Health Expenditure Database (GHED), total health expenditure in the BRICS countries rose from 4% to 16% of GDP at purchasing power parity over the past decade.

The relationship between health spending and economic growth is multifaceted and mediated by several factors, such as life expectancy, mortality rates, and health insurance coverage.

Bustamante and Shimoga (

2018) note that health expenditure exerts a stronger influence in low- and middle-income countries than in high-income economies. Given that several BRICS members fall within the low- and middle-income category, they face persistent challenges in achieving adequate healthcare coverage and require more targeted support. Importantly, the effectiveness of healthcare investment depends not only on the amount allocated but also on its efficient use in strengthening social welfare systems and improving population health outcomes.

Within the framework of endogenous growth theory, health expenditure is conceptualized as a critical component of human capital investment that is capable of influencing long-term economic growth. However, the strength and direction of this relationship vary according to structural and institutional conditions, including the development of national healthcare systems, the composition of the economy, and the fiscal and monetary policies in place. The empirical literature has examined this relationship using a wide range of econometric models and datasets, yielding contradictory results. These divergences underscore the importance of country-specific analyses, particularly in emerging economies such as the BRICS, where the dynamics of health spending and growth may differ from those observed in high-income contexts.

This study employs a dynamic endogenous growth panel model for several methodological reasons. First, panel data provide a larger number of observations by combining cross-sectional and time-series dimensions, thereby increasing the efficiency of estimation. The repeated observations over time also reduce standard errors compared with purely time-series approaches. Second, panel data are well suited to analyzing dynamic processes and capturing phenomena that evolve over time. Third, the time dimension requires consideration of serial correlation, while the structure of panel data typically reduces collinearity among explanatory variables, mitigating multicollinearity issues. Fourth, the use of panel data generates more degrees of freedom, enhances variability, and improves efficiency in addressing heteroscedasticity. Fifth, panel models allow for the incorporation of unobserved heterogeneity across units, which may be correlated with observed factors, thus enabling more accurate inference. Moreover, they facilitate a clearer distinction between unobserved heterogeneity and dynamic processes. Finally, the presence of global factors often induces cross-sectional dependence, which can be addressed through approaches such as the unobserved common factors method or fixed-effects specifications adapted for panel data.

To examine the impact of per capita health expenditure on per capita GDP in the BRICS countries, we apply a series of econometric tests. First, to assess cross-sectional dependence among the BRICS economies, we employ the Breusch–Pagan Lagrange Multiplier test (

Breusch & Pagan, 1980), Pesaran’s CD test, and the scaled LM test (

Pesaran, 2004). Second, the homogeneity or heterogeneity in slope coefficients is evaluated using the

Hsiao (

2014) test. Third, to investigate stationarity, we apply two second-generation unit root tests that account for cross-sectional dependence and heterogeneity in both variables and model residuals: the

Bai and Ng (

2004) PANIC (Panel Analysis of Non-stationarity in Idiosyncratic and Common components) test and the

Pesaran (

2007) CIPS test, which extends the standardized

Im et al. (

2003) procedure by incorporating a common cross-sectional factor. Finally, to test for cointegration, we use the second-generation panel ARDL framework developed by

Pesaran et al. (

1999,

2001), which accommodates cross-sectional dependence, slope heterogeneity, and variables integrated of different orders, I(0) or I(1).

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents a literature review. The theoretical framework is presented in

Section 3. The data are presented in

Section 4.

Section 5 describes the diagnostic tests of the panel models,

Section 6 presents the empirical results, and

Section 7 presents the discussion. Finally,

Section 8 presents conclusions and policy implications.

2. Literature Review

For the scope of this research, the literature review examined empirical studies that analyzed the direct relationship between health expenditure and economic growth using methodologies such as panel cointegration, GMM, ARDL, and causality tests. Also, studies that considered health expenditure alongside other human capital variables, i.e., education and demographic structure, were reviewed. Finally, cross-country evidence highlighting the heterogeneity in the health–growth nexus across income levels, governance settings, and macroeconomic environments was examined. Within this framework, a substantial body of research has explored how health spending influences growth, either as a standalone determinant or in conjunction with factors such as education, physical capital, inflation, household consumption, wages, and demographic trends. Despite this extensive evidence, the results remain mixed, underscoring the complexity of the relationship and the need for context-specific analysis in emerging economies such as the BRICS.

Ghosh and Gregoriou (

2006), using an endogenous growth model and GMM estimation for 15 developing countries (1972–1999), reported that higher health expenditure was associated with lower economic growth. The authors suggested that this may reflect inefficiencies in public spending, weak institutions, or the crowding out of productive investment in countries with limited fiscal capacity. In contrast,

Maitra and Mukhopadhyay (

2012) analyzed 12 Asia–Pacific economies and found strong evidence of cointegration among education, health expenditure, and economic growth during 1981–2011. Their results indicate that human capital accumulation, measured through both education and health, acts as a long-run driver of output, although the strength of relationships varied substantially across countries, revealing considerable structural heterogeneity.

Similarly,

Hatam et al. (

2016) used Westerlund’s cointegration test and found that in ECO countries between 1995 and 2009, both health and education spending exerted significant long-run growth effects, reaffirming the view that human capital is a key channel linking public expenditure and productivity. In G7 economies,

Namini (

2018) highlighted that inflation exerted a stronger influence on health expenditure than growth, revealing that price effects often overshadowed income dynamics in high-income economies. Nonetheless, short-run Granger causality ran from economic growth and inflation to health expenditure, consistent with countercyclical fiscal responses in advanced countries.

More recent studies confirm the diversity of outcomes.

Ozyilmaz et al. (

2022) employed panel Fourier Toda–Yamamoto causality tests for 27 EU countries (2000–2019) and identified robust bidirectional causality, suggesting that health investment both drives and responds to economic growth.

Penghui et al. (

2022) showed that multiple dimensions of health inputs—including finance, personnel, assets, and insurance—positively influenced provincial growth in China (2012–2018). In the Western Balkans,

Qehaja et al. (

2023) reported that government health spending significantly promoted economic growth (2000–2020), reinforcing the argument that public investment in health remains crucial in economies with constrained private healthcare capacity. Meanwhile,

Dritsaki and Dritsaki (

2023b) analyzed G7 countries through a heterogeneous panel framework and identified stable long-run cointegration among healthcare spending, GDP, and CO

2 emissions, with causality flowing from environmental degradation to healthcare expenditure—highlighting the interdependence between environmental stress and health system costs.

Further evidence highlights regional variations.

Sethi et al. (

2024) documented a long-run cointegration and bidirectional causality between health expenditure and growth in South Asian economies (1996–2018).

Ikpe et al. (

2024), focusing on 27 Sub-Saharan African countries (2005–2021), found that while health expenditure positively influenced growth, governance quality indicators, such as rule of law and accountability, had negative associations.

Hu and Wang (

2024) used a dynamic panel threshold model for 33 OECD countries and demonstrated that the effect of health spending on growth is non-linear: health expenditure promoted growth only when household consumption and wage levels exceeded specific thresholds; below these levels, the effect was negative. Their findings highlight that the macroeconomic environment mediates the return to health investment.

Ginn (

2025) showed that the elasticity of healthcare spending with respect to income varied substantially across 177 economies, weakening especially during periods of economic stagnation or contraction. His results imply that the responsiveness of health systems to economic cycles differs between low-, middle-, and high-income countries, with the poorest economies facing the greatest vulnerabilities.

Finally,

Şentürk et al. (

2023) analyzed the new EU member states through second-generation panel econometric techniques that explicitly account for cross-sectional dependence and slope heterogeneity, providing robust evidence that health expenditure contributes to sustainable development primarily via its interaction with human capital formation. Their findings indicate that the productivity-enhancing effects of health expenditure are substantially amplified when accompanied by improvements in educational attainment and higher institutional quality. Also,

Zhang et al. (

2023) developed an overlapping-generations (OLG) model, demonstrating that public health expenditure stimulated long-run economic growth by augmenting labor productivity and reducing the economic losses associated with pollution-induced health deterioration. Their calibrated simulations for China highlight that the growth effects of health spending are contingent on the strength of environmental governance, underscoring the importance of policy complementarities between health investment and environmental regulation. Taken together, these studies suggest that the growth effects of health expenditure are context-dependent, shaped by structural, institutional, and macroeconomic factors. While many analyses support a positive long-run association, evidence of negative or heterogeneous effects underscores the importance of country-specific conditions and the role of complementary variables, such as education, governance quality, and household welfare, in mediating the health–growth nexus.

3. Theoretical Framework

The Solow growth model (1957) is an exogenous model of economic growth that analyzes changes in the level of output in an economy over time. These changes refer to the rate of population growth, the rate of savings, and the rate of technological progress. The Solow growth model (1957) is the first neoclassical growth model and is based on the Keynesian Harrod–Domar model, which emphasizes the importance of saving and investment as determinants of growth. The Solow model (1957) is the basis for the modern theory of economic growth. Combining the neoclassical growth theory of

Solow (

1957) with the endogenous growth theory of

Barro and Sala-I-Martin (

2004), we construct a model of economic growth starting from the

Cobb and Douglas (

1928) production function. The expression of the model is as follows:

In the model above, natural capital, education, per capita health expenditure, and population growth rate are endogenous variables that contribute to the productivity of per capita GDP.

In its logarithmic form, function (1) can be formulated as follows:

where

: the logarithm of per capita gross domestic product at purchasing power parity.

: the logarithm of physical capital at purchasing power parity.

: the logarithm of the average education rate of people over 25 years old.

: the logarithm of per capita health expenditures at purchasing power parity.

: the logarithm of the population growth rate of the country.

: an error term.

Per capita gross domestic product at purchasing power parity

Per capita gross domestic product (GDP) at purchasing power parity (PPP) is defined as the value of all final goods and services produced within an economy in a given year, adjusted for differences in price levels across countries and divided by the average population for that year. A higher level of per capita GDP generally indicates improved access to basic needs and is positively associated with a healthier and more productive workforce. Moreover, countries with stronger socioeconomic environments provide more favorable conditions for the development of both human and natural capital, thereby supporting sustained economic growth.

Physical capital

Within economic theory, physical capital is recognized as one of the three fundamental factors of production and constitutes a core input in the production function. As described by

Mankiw and Taylor (

2023), physical capital encompasses man-made assets employed in the production of goods and services, including machinery, equipment, buildings, infrastructure, and inventories. In the present study, physical capital is proxied by gross fixed capital formation, a component of gross domestic product (GDP) expenditure that reflects the share of newly created value added in an economy allocated to investment rather than consumption.

Education level

According to the

World Economic Forum (

2016), education may be defined as the accumulation of skills, competencies, and other attributes that enhance worker productivity. As a key component of human capital, education improves individual efficiency and contributes to overall economic performance. The

World Economic Forum (

2016) identifies three primary channels through which education influences productivity, namely, (i) by strengthening the collective capacity of the labor force to perform tasks more efficiently; (ii) by facilitating the diffusion of knowledge related to new products and technologies; and (iii) by fostering creativity, thereby enhancing a country’s potential to generate new knowledge and technological innovation (

Grant, 1917).

Per capita health expenditures

Health is widely regarded as a fundamental determinant of economic growth.

Mushkin (

1962) conceptualized health as a form of capital, emphasizing that investments in healthcare can stimulate income growth and enhance productivity at the national level. As healthcare constitutes a critical dimension of human capital investment, it contributes directly to human capital accumulation, which is central to the endogenous growth framework.

Population growth rate

The relationship between population dynamics and economic growth has long been the subject of scholarly debate, with empirical findings offering no definitive consensus. Population growth can serve as a driver of economic expansion, as a substantial proportion of the population constitutes the labor force, a fundamental input to production. At the same time, the ultimate objective of development is to enhance population well-being. Modern growth theories diverge significantly from classical perspectives in their treatment of population. Neoclassical models regard population as an exogenous variable and typically predict a negative relationship between population growth and per capita income. By contrast, endogenous growth models (

Romer, 1990) posit a positive association, suggesting that larger populations may contribute to knowledge creation and technological progress. More recent theoretical frameworks endogenize population growth, yielding effects that differ in magnitude, direction, and sign (

Bucci et al., 2019). Despite this extensive literature, there remains no consensus on whether population growth is ultimately beneficial, neutral, or detrimental to long-run economic performance.

4. Data

This study examines the relationship between health expenditures and economic growth in the BRICS countries over the period 2000–2021. The analysis is based on annual data obtained from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators database. A detailed description of the variables employed in this study is presented in

Table 1.

Table 2

presents the descriptive statistics for the corresponding variables.

In this study, the variables exhibiting the greatest volatility are physical capital and GDP per capita, whereas population share, per capita health expenditure, and the education rate of individuals over 25 years display relatively low variability, with values concentrated more closely around their means. Analysis of skewness indicates that four variables are positively skewed, while one variable is negatively skewed, reflecting asymmetries in their distributions. Skewness captures the extent and direction of the distributional “tail”, while kurtosis reflects its peakedness: values greater than three suggest a leptokurtic distribution with heavy tails, whereas values below three indicate a platykurtic distribution with lighter tails. Results from the Jarque–Bera test confirm that all variables in the model deviate from normality.

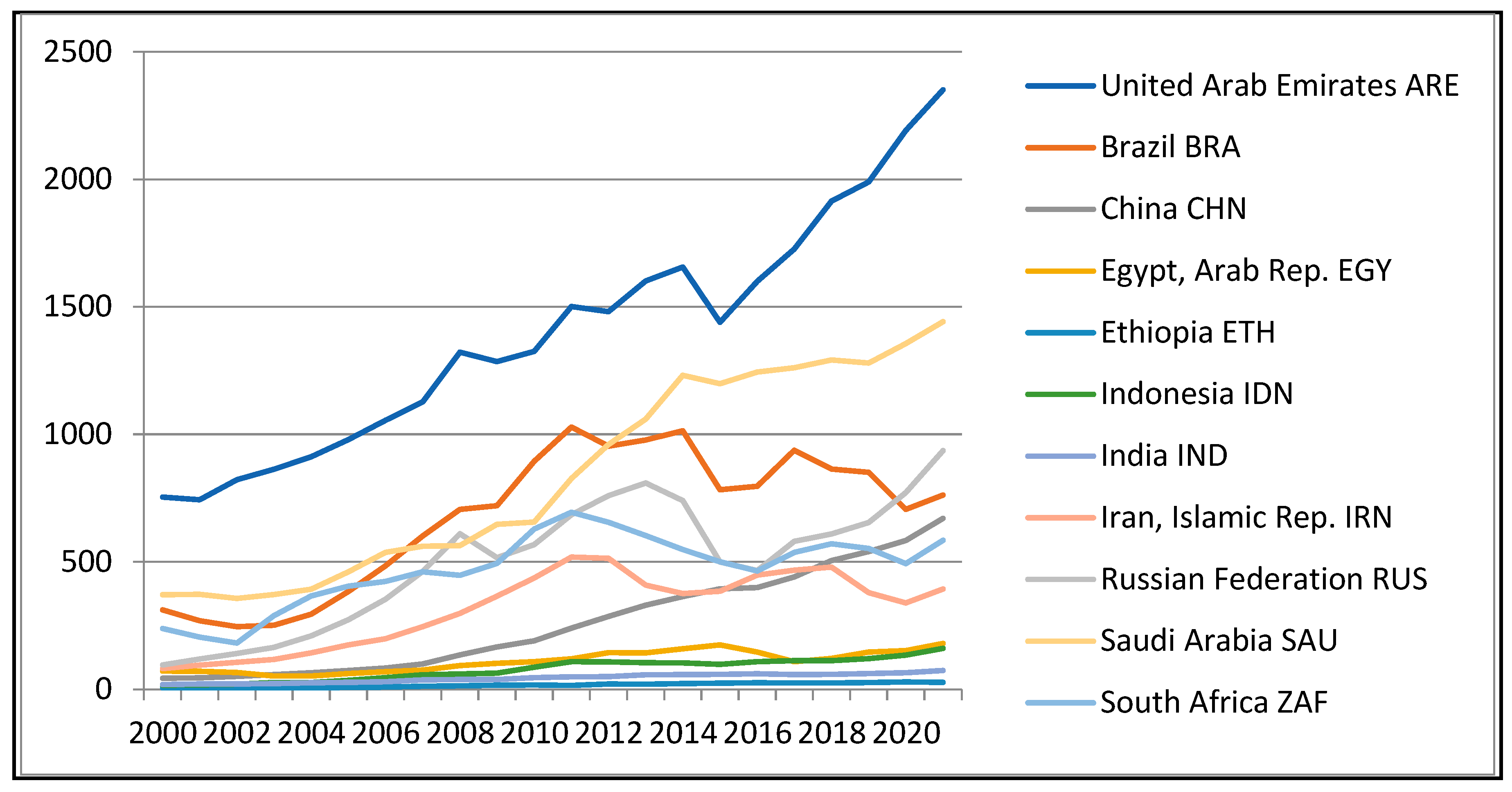

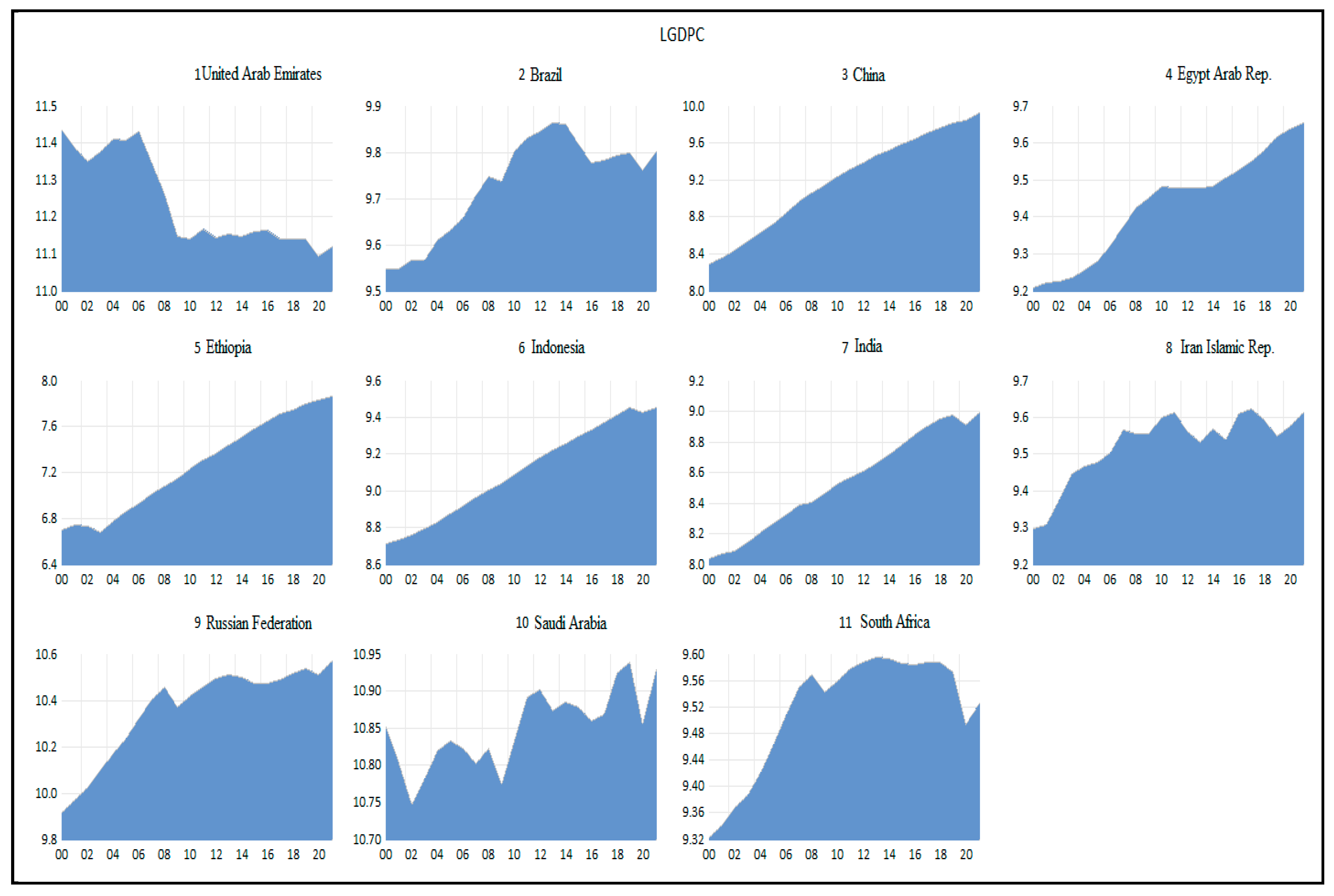

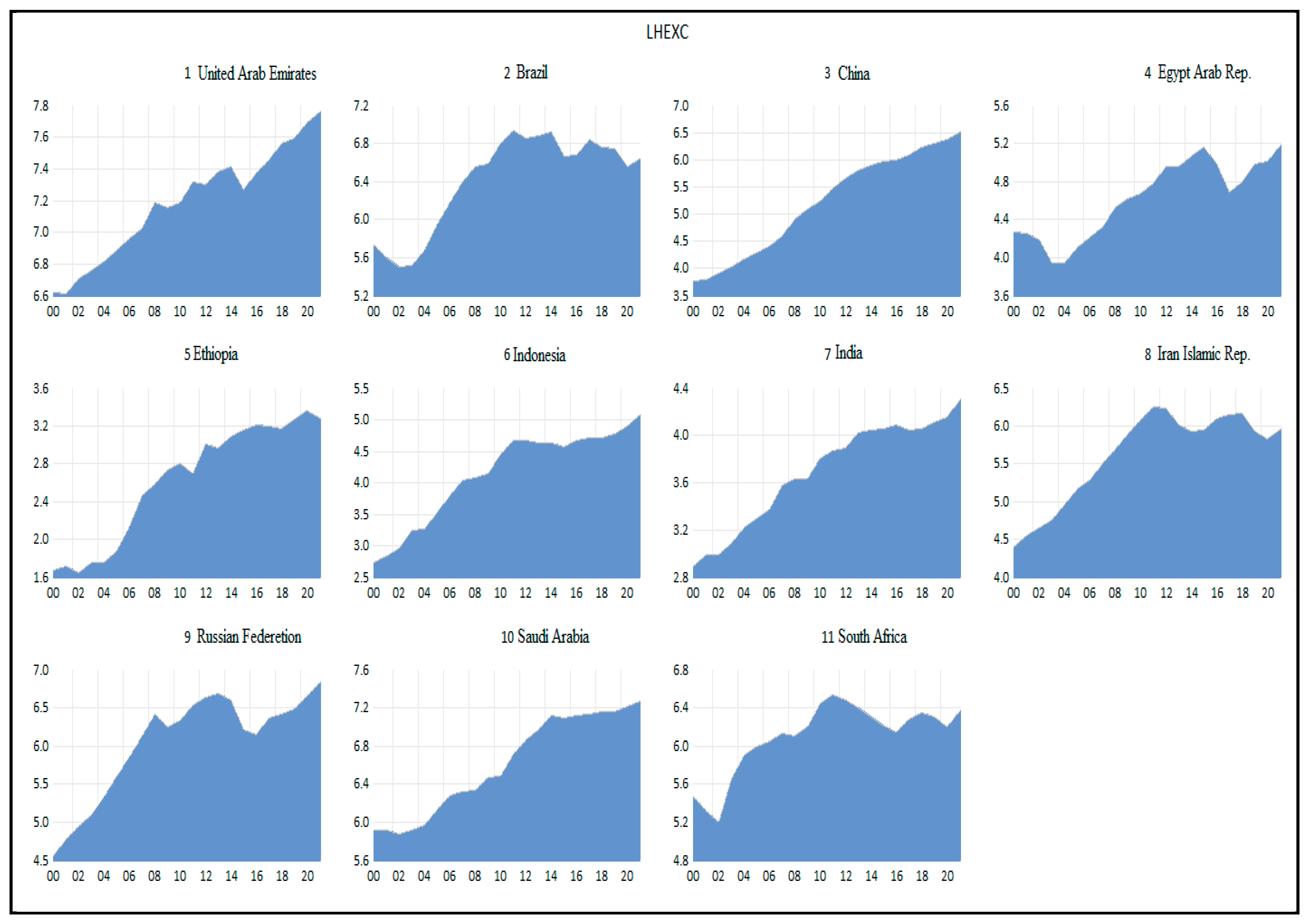

Figure A1 and

Figure A2 in

Appendix A illustrate the evolution of GDP per capita (GDPC) and health expenditure per capita (HEXC) in the BRICS countries during 1990–2021. As shown in

Figure A1, countries with GDP per capita above the BRICS average (22,215.43 PPP dollars) over the study period include the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and the Russian Federation.

Figure A2 indicates that per capita health expenditures exceeding the BRICS average (427.13 PPP dollars) were observed in the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Brazil, the Russian Federation, and South Africa.

Figure A3 and

Figure A4 in

Appendix B present the time series of GDP per capita and health expenditure per capita, respectively. Overall, most BRICS countries experienced an upward trend in GDP per capita during the period under review, with notable exceptions: the United Arab Emirates, which recorded a decline between 2007 and 2021; Brazil, from 2013 to 2021; South Africa, from 2011 to 2021; and Iran, which remained stable between 2011 and 2021. Health expenditure per capita generally increased across the BRICS countries, though temporary declines were observed in Brazil, Egypt, Iran, the Russian Federation, and South Africa during the COVID-19 pandemic.

5. Methodology

The methodological strategy of this study is based on the endogenous growth framework, which conceptualizes health expenditure, education, physical capital, and demographic dynamics as integral components of human capital accumulation and long-run productivity. Building on this theoretical foundation, the empirical approach employs second-generation panel econometric techniques capable of handling the key data features present in the BRICS economies, namely, cross-sectional dependence, slope heterogeneity, and mixed orders of integration.

5.1. Diagnostic Tests of Panel Models

5.1.1. Cross-Sectional Dependency Tests

Accounting for cross-sectional dependence is a critical requirement in panel data regression. Failure to address cross-sectional dependence can result in residual correlation, reduced estimator efficiency, and invalid statistical inference. Panel estimation methods that neglect cross-sectional dependence and heterogeneity typically yield biased and inconsistent estimates. Consequently, diagnostic testing for cross-sectional dependence and slope homogeneity represents a fundamental step that researchers must undertake prior to conducting panel data analysis. In this study, cross-sectional dependence among the BRICS countries was assessed using three complementary statistical tests: the Breusch–Pagan Lagrange multiplier test (

Breusch & Pagan, 1980), Pesaran’s CD, and scaled LM tests (

Pesaran, 2004). The null hypothesis of this test is “H0: No cross-sectional dependence”.

Table 3 below lists the results of cross-sectional dependence.

The results of the above table show that the null hypothesis is rejected both for the cross-sectional dependence (correlation) of the time series and between the residuals of the model. In other words, we can say that the cross-sectional dependence of variables is correlated across countries. That is, global shocks, regional trends, or economic policies similarly affect the variables in all BRICS countries. The cross-sectional dependence of the residuals shows that the deviations in the predicted and actual values of GDP per capita are not independent across countries. For example, a shock to the Chinese economy that is not captured in the model variables can also affect the deviations in other countries. This usually reflects the existence of unobserved factors or global shocks, such as financial crises, geopolitical tensions, and pandemics, that affect all countries simultaneously. Therefore, we proceeded to tests and estimation techniques that can take cross-sectional dependence into account.

5.1.2. Homogeneity–Heterogeneity Test

In linear panel models, the homogeneity–heterogeneity issue mainly concerns the individual slopes of the regression. Since, in most cases, the homogeneity in the slope cannot be determined a priori, many authors have developed tests to investigate this assumption. Furthermore, in panel data analysis, unobserved heterogeneity is assumed to be captured by individual-specific constants, which are considered either fixed or random. Ignoring this form of heterogeneity can lead to biased results. Therefore, it is important to test the assumption of slope homogeneity before applying standard panel data techniques. Homogeneity–heterogeneity tests can provide information about the structural differences in the series across countries. Furthermore, in a panel data sample, it is necessary to check for homogeneity or heterogeneity across countries in the specification generator process data. Also, homogeneity in slope coefficients is important for the selection of the unit root, cointegration, and causality testing (

Dritsaki & Dritsaki, 2023a). The homogeneity–heterogeneity in this work was examined with the tests of

Hsiao (

2014). The general null hypothesis of this test is, “H0: There is general homogeneity among countries”. If we reject the null hypothesis, then we say that there is general heterogeneity among countries.

Hsiao’s (

2014) panel data tests, according to

Khouiled (

2018), are examined in three stages. In the first stage, the null hypothesis generally tests for homogeneity across countries. In the second stage, the homogeneity in country slopes is tested. In the third stage, the homogeneity in country constants is tested.

Table 4 presents the three stages of

Hsiao’s (

2014) test.

Based on the estimated statistical tests and the corresponding p-values in the first row, the results indicate that the null hypothesis of homogeneity is rejected. Therefore, we can say that we have heterogeneity between countries. Based on the second row of the table, we again have a rejection of the null hypothesis, so we can say that we have heterogeneity in slopes among the BRICS countries. Based on the third row, we again have a rejection of the null hypothesis; therefore, we also have heterogeneity in the constants of the BRICS countries. So, we have heterogeneity in the slopes and heterogeneity in the constants of the BRICS countries. Therefore, we can say that there is a difference in efficiency in the GDP per capita of the BRICS countries in relation to the dependent variables of the model we examined.

Specifically, heterogeneity in the constants means that each country has a different “starting point” of per capita productivity. Also, the constants reflect differences that do not depend on the variables of the model but on the institutional framework, culture, natural resources, and structure of the economy. In other words, we would say that even if the BRICS countries had the same values of the independent variables, their per capita productivity would differ. Heterogeneity in slopes means that the effect of an independent variable (e.g., per capita health expenditure) on per capita productivity is not the same for all countries. For example, a 1% increase in per capita health spending may increase per capita productivity in China but less so in Brazil due to different institutions or technological base.

5.1.3. Testing for Unit Roots and Cointegration

In order to use unit root tests for panel data, we must first examine whether there is cross-sectional dependency (correlation) and homogeneity in the panel data. As we mentioned, testing for cross-sectional dependence and homogeneity is important for choosing the unit root, cointegrating, and testing for causality. The previous literature assumed that in a panel data model, the confounding terms show little or no dependence on each other. These tests are categorized as first-generation unit root tests. These tests are invalid and have severe size distortions if the independence assumption is not satisfied (see

Banerjee et al., 2004). This led to the development of second-generation panel unit root tests, which relax the cross-sectional independence assumption.

Second-Generation Panel Unit Root Tests

To test whether the data are stationary, we used second-generation unit root tests, the tests of

Bai and Ng (

2004) and

Pesaran (

2007), which allow for cross-strata dependence and heterogeneity between the variables and the residuals of the model, as well as modeling cross-sectional dependence using a small number of unobserved common factors. The

Bai and Ng (

2004) test allows common factors to have differential effects on different cross-sectional units, while the

Pesaran (

2007) test allows at most one common factor where cross-sectional dependence is modeled in the form of a low dimensional common factor model, which is estimated and adjusted before testing for the unit root in the panel data (

Barbieri, 2006).

Bai and Ng test

The test by

Bai and Ng (

2004) uses the PANIC (Panel Analysis of Non-stationarity in Idiosyncratic and Common components) model, which allows for non-stationarity in panel data from either a common source, from idiosyncratic errors, or from both. Therefore,

Bai and Ng (

2004) focus on a consistent estimation of the common factors and error terms to test the properties of these series separately with the following model:

Model (3) describes the observed data in terms of a deterministic part, a common stochastic component, and the idiosyncratic error, . is a dimensional vector and constitutes a vector of factor loadings. is a dimensional vector of the common factors, which we assume we know.

The common factor

and the idiosyncratic terms

can be either zero-integration I(0) or first-order integration I(1) in a first-order autoregressive process

with a polynomial lag structure of

i,

i,

d. written as follows:

where

a stationary moving average process MA with

.

If we assume that the determinant component

can be represented by individual effects

without trend, then model (3) can be formulated as follows:

In this case, the series is said to be non-stationary if at least one common factor from the vector is non-stationary or the idiosyncratic error is non-stationary. These two terms above are very likely not to have the same dynamic properties; that is, one could be stationary and the other not. In other words, we would say that some components of could be integrals of order zero I(0) and others integrals of order one I(1), as well as terms of the idiosyncrasy . However, it is known that a series is defined as the sum of components that have different dynamic properties. Therefore, it is difficult to test the stationarity of the series if it contains a large stationary component.

This is why, instead of directly testing for non-stationarity in the series,

,

Bai and Ng (

2004) propose to separately test for the presence of a unit root in the common individual components. For this reason, the authors named this procedure PANIC (Panel Analysis of Non-stationarity in the Idiosyncratic and Common components). The validity of the PANIC procedure therefore depends on the possibility of obtaining estimators

and

that retain their degrees of integration, whether they are I(0) or I(1). In other words, we would say that common variations must be extracted without mentioning the assumptions of stationarity and the restrictions of cointegration. To achieve this, Bai and Ng estimate the common factors and the idiosyncratic terms in the first differences, using the following model:

where

,

, and

.

To calculate the components of temperament,

Bai and Ng (

2004) use the Dickey and Fuller augmented control statistic with

p time lags. Furthermore, since controlling for idiosyncratic errors jointly for a homogeneous unit root is equivalent to controlling for non-cointegration between individuals, strata, and groups of the time series.

We should also point out that

Bai and Ng’s (

2004) test, through the PANIC model, can test for unit roots in the unobserved factors and in the idiosyncratic component separately, while in

Pesaran’s (

2007) test, the unit root test is performed only in the idiosyncratic components.

Pesaran test

The

Pesaran (

2007) test is an augmented version of the standardized test of

Im et al. (

2003) and is called Cross-sectionally Augmented IPS-CIPS. It assumes that the panel data have a common structural factor (common cross-sections factor). The

Pesaran (

2007) test uses the cross-sectional statistics of the augmented Dickey–Fuller regression (cross-sectional augmented Dickey–Fuller—CADF) given as follows (see

Pesaran, 2007, p. 269):

where

,

,

, and

are the slope coefficients estimated by the augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test for each unit (country),

,

is the mean of the lags in the levels,

is the mean of the first differences, and

are the error terms.

In the above regression (8), the two hypotheses we examine are the following:

(non-stationary process);

for at least some (partially stationary process).

By adding time lags, in regression (8), Pesaran’s test is modified as follows (see

Pesaran, 2007, p. 283):

The assumptions in the above regression are the same as in regression (8). In other words, we would say that in Equation (9), Pesaran modified the statistics of the equation of

Im et al. (

2003) based on the average of the cross-sectional statistics of the augmented Dickey–Fuller regression (CADF), which is referred to as the cross-sectional statistics of the augmented IPS equation (Cross-Sectionally Augmented Im, Perasan, and Shin—CIPS) and is given as follows:

where

(

N,

T) is the

(

t-statistic) from the OLS estimate of function (9). Or

where

is the cross-sectionally augmented Dickey–Fuller statistic for

i-th cross-sectional units—strata (countries)—given by the t-ratio of

in regression (8).

Second-Generation Panel Cointegration Tests

The presence of cross-sectional dependencies in panel data is subject to large-scale distortions according to

Banerjee et al. (

2004,

2005). This problem becomes more severe as the number of cross sections increases. To overcome these problems, both unit root tests on panel data and second-generation cointegration tests have been developed.

ARDL cointegration test

Pesaran et al. (

2001) and

Pesaran and Shin (

1998) presented an ARDL model that allows, in addition to the cross-sectional dependence of the panel units and heterogeneity, the variables to be integrated on different orders: I(0) or I(1). The ARDL model maintains efficient and consistent estimators by removing endogeneity issues and adding lag lengths to both exogenous and endogenous variables. Furthermore, the ARDL model distinguishes between short-run and long-run coefficients and is reliable for small sample sizes.

Pesaran and Shin (

1998) argue that even if the sample size is small, the long-run coefficients are consistent, as are the short-run coefficients. Equation (2) is formulated in an ARDL model as follows:

where

are the time periods,

are the BRICS countries,

p represents the lags of the dependent variable, and

q represents the lags of the independent variables.

is the error term, which is assumed to be white noise and differs for each country and period.

By transforming Equation (12), we obtain the panel ARDL(

p,

q1,

q2,

q3,

q4) error correction model:

where ∆ is the first difference of variables. Also,

α1–

α5 are the short-run coefficients, while

β1–

β5 are the long-run coefficients of per capita gross domestic product at purchasing power parity, of physical capital at purchasing power parity, of the average education rate of people over 25 years old, of per capita health expenditures at purchasing power parity, and of the population growth rate of every country, respectively.

Before estimating model (13), it is necessary to first establish the presence of cointegration between the variables. For the cointegration of the variables,

Pesaran et al. (

2001) propose the Wald

F distribution, which is an asymptotic distribution for the joint significance of the coefficients of the variables at their levels. The null hypothesis of non-cointegration between the variables in Equation (13) is as follows:

(there is no cointegrating long-run relationship).

The alternative hypothesis for cointegrating is as follows:

(there is a cointegrating long-run relationship).

If cointegration is established, that is, a long-term relationship is created between the variables, Equation (12) can be expressed as an error correction model as follows:

where

is the error correction part and

is the speed of adjustment from the short-run dynamics to the long-run equilibrium. It should be mentioned here that for the existence of a long-run equilibrium between the GDP per capita of the BRICS countries and the explanatory variables, the coefficient

is expected to be negative and statistically significant.

6. Empirical Results

Diagnostic tests for cross-sectional dependence and homogeneity are among the basic tests that a researcher should investigate before conducting panel data analysis. Omission of testing for cross-sectional dependence and homogeneity can lead to spurious and misleading findings. The results of these tests are important for the selection of additional econometric tests. The results of the model showed that the variables and residuals exhibit cross-sectional dependence. This result means that shocks to the variables of one country affect the other BRICS countries. Furthermore, the results showed heterogeneity across countries in both the slopes and constants of the BRICS countries. Therefore, we can say that there is a difference in efficiency in the GDP per capita of the BRICS countries in relation to the dependent variables of the model we examined. Therefore, we must proceed to tests and estimation techniques that can take into account cross-sectional dependence and heterogeneity in the variables. The unit root tests of

Bai and Ng (

2004) and

Pesaran (

2007), as well as the second-generation cointegration ARDL test, proved to be the most suitable for estimating the model we examined.

Assuming that the panel data in our work have a common structural factor (common cross-sections factor), we use the

Pesaran (

2007) CIPS approach that takes into account both cross-sectional dependence and heterogeneity. Also, to test for the unit root in common and idiosyncratic components separately, we use the test introduced by

Bai and Ng (

2004) with the PANIC (Panel Analysis of Non-stationarity in Idiosyncratic and Common components) model, which allows for non-stationarity and non-cointegration in panel data that come from either a common source, or idiosyncratic errors, or both.

Furthermore, testing for idiosyncratic errors together for a homogeneous unit root is equivalent to testing for non-cointegration between individuals, strata, and groups of the time series.

Table 5 below presents the results of the second-generation unit root tests of

Bai and Ng (

2004) and

Pesaran (

2007).

The tests mentioned above also differ in the way they gather information. The PANIC test is based on the pooled p-values of the individual test statistics. This has the advantage of allowing for greater heterogeneity in the autoregressive coefficients. The Pesaran CIPS test is based on pooled t-statistics.

As shown in the table above, Bai and Ng’s test shows the rejection of the null hypothesis of non-stationarity and non-cointegration of the dependent strata across all variables in the model. On the contrary, Pesaran’s test does not reject the null hypothesis of the unit root of the dependent variables in all the variables of the model (except the LGDPC variable). So, we cannot make an unambiguous decision on the order of integration of the variables from both tests we use for the groups of BRICS countries we examined. Therefore, the variables under examination can be considered as unit root processes. Thus, to test for cointegration, we use the ARDL test of

Pesaran and Shin (

1998), which allows, in addition to the heterogeneity and cross-stratum dependence of the panel units, the different orders of integration of the variables: I(0) or I(1).

Therefore, before estimating the ARDL model, it is necessary to first establish the presence of cointegration between the variables.

Table 6

presents the results of the Wald test for the joint significance of the coefficients of the variables at their levels.

The results in

Table 6 show that there is cointegration among the variables in the model we examined. This means that there is a stable long-run relationship between per capita productivity and the explanatory variables (natural capital, education, per capita health expenditure, and population growth rate). In other words, we can say that the variables have a common long-term equilibrium, that is, per capita productivity, and the determinants in the BRICS countries are consistent in the long term, even if there are short-term deviations. In conclusion, we can say that the BRICS countries, despite their short-term differences, follow a common long-term productivity relationship with the determinants of our model.

Pesaran et al. (

1999) propose the Pooled Mean Group (PMG) estimator as a solution to heterogeneity bias in estimating dynamic panel coefficients caused by heterogeneous slopes. The Pooled Mean Group (PMG) estimator, according to

Pesaran and Smith (

1995), considers a lower degree of heterogeneity, since it imposes homogeneity in the long-run coefficients while still allowing for heterogeneity in the short-run coefficients and error variances. Furthermore, the Pooled Mean Group (PMG) estimator can be interpreted as an analysis of long-run elasticities (for example, how much per capita health spending affects per capita productivity in the long run) while adjusting for short-run differences.

Table 7 and

Table 8 present the long-run and short-run results, respectively, of the Pooled Mean Group (PMG) estimator of the panel ARDL(1,1,1,1,1) model.

The results of the ARDL(1,1,1,1,1) model in

Table 7 show that all variables in the model significantly affect the per capita GDP of the BRICS countries in the long run. The greatest increase in GDP per capita is caused by the average education rate among people over 25 years old and the population growth rate. Specifically, the results suggest that an increase in the average educational attainment of people over 25 years of age and in the population growth rate by 1% leads to an increase in GDP per capita in the BRICS countries by 0.473% and 0.435%, respectively. In contrast, an increase in natural capital and per capita health spending by 1% leads to an increase in per capita GDP by 0.284% and 0.194%, respectively.

Regarding the results in

Table 8, we found that the error correction coefficient, which represents the speed of adjustment from short-run to long-run equilibrium, is negatively less than unity and statistically significant at the 1% level. Furthermore, the error correction coefficient shows the speed with which the production process adjusts to deviations from the long-run equilibrium. This deviation correction is 79.2% for each year considered satisfactory for the long-run equilibrium. The variables of natural capital and the average rate of education for people over 25 years old seem to have no short-term impact on GDP per capita in the BRICS countries. Conversely, per capita health spending has a positive effect on per capita GDP, while the population growth rate has a negative effect on per capita GDP.

Appendix C reports the short-run results of the panel ARDL models estimated using the Pooled Mean Group (PMG) approach, which allows for parameter heterogeneity across the BRICS countries. The error correction term, reflecting the speed of adjustment toward long-run equilibrium, is statistically significant and negative at the 1% level in most countries, with the exception of the Russian Federation. The results reveal considerable variation across countries. In several cases—such as Brazil, China, Egypt, Ethiopia, India, Iran, and South Africa—per capita health expenditure exerts a positive short-run effect on GDP per capita, while population growth and education show mixed or negative effects. Natural capital contributes positively in some countries (e.g., China, Egypt, Ethiopia) but negatively in others (e.g., Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa). The heterogeneity in these findings underscores the absence of a uniform short-run relationship across the BRICS economies. Moreover, the lack of statistical significance in the error correction term for the Russian Federation indicates that no long-run equilibrium relationship can be established, restricting interpretation of the results to short-run dynamics only.

7. Discussion

The relationship between public health spending and economic growth has become an important research topic in public health. Public health care coverage is a social welfare policy implemented by governments that contributes to improving the quality and well-being of people. Considering the increased health spending worldwide, it is necessary to understand the relationship between health spending and economic growth, as well as the trends that exist in certain countries and the heterogeneity between countries. Exploring these issues can serve as a reference for the BRICS group of countries to formulate appropriate policies for their healthcare systems and improve their existing healthcare systems. Given that many of the BRICS countries are low- and middle-income, their healthcare standards need further strengthening. The trajectory of the BRICS countries over time depends on many factors. First and foremost is the way China’s power is evolving. There is a growing consensus that China’s long-term growth will continue to slow, which will reduce the opportunities the Chinese market has to offer for BRICS members. However, the amount spent on healthcare by all BRICS nations should be effectively invested in a better social welfare system that will improve the health and well-being of citizens.

From the results in

Table 2, we observe that physical capital has the greatest volatility of all the variables in the model for the BRICS group of countries, which means that the values of physical capital are distant from the average value. From diagrams A-1, we observe that the countries that present a higher per capita GDP than the average of the BRICS countries (22,215.43) are the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and the Russian Federation, which produce oil and natural gas. From chart A-2, we observe that the countries that have higher per capita health expenditures than the average of the BRICS countries (427.13) are the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Brazil, the Russian Federation, and South Africa.

In

Section 5, we mention that before testing for stationarity and cointegration in the panel data, tests for cross-stratum dependence and homogeneity–heterogeneity among the BRICS country variables are required. This is necessary because omitting these tests can lead to spurious and misleading findings. The existence of global factors creates an interdependence between cross-sectional units. To address this interdependence, the literature has adopted an approach called the unobserved common factors approach or the interactive fixed effects approach. In this context, the results of the tests showed that there is cross-sectional dependence and heterogeneity in the variables. This shows that a shock that occurs in one country will affect the other BRICS countries. In a globalizing world, some events that occur in one country can affect other countries.

The results of the findings that emerged from the diagnostic tests of cross-sectional dependence and heterogeneity in our variables led to the tests of unit root and second-generation cointegration. The findings of the tests of both

Bai and Ng (

2004), with the PANIC (Panel Analysis of Non-stationarity in Idiosyncratic and Common components) model, and

Pesaran (

2007) could not show an unambiguous decision on the order of integration of the variables. Therefore, the variables under examination can be considered as unit root processes.

After the existence of non-stationarity of the variables, we were led to the control of the ARDL cointegration of

Pesaran and Shin (

1998), which allows, in addition to the heterogeneity and cross-stratification dependence of the panel units, the different orders of integration of the variables: I(0) or I(1).

The different orders of integration of the model variables can be interpreted as follows:

The variables do not all evolve at the same rate over time.

Some of the variables are more short-term (fixed), while others have long-term trends.

This leads us to think that the relationships in the model we studied are long-term (cointegrated) or short-term (direct effects).

The results of the Wald F distribution showed that there is cointegration in the group of BRICS countries. The estimation of the ARDL(1,1,1,1,1) cointegration model in

Table 7 shows that all the variables in the model significantly affect the GDP per capita of the BRICS countries in the long run. The largest increase in GDP per capita is caused by the average education rate of people over 25 years old and the population growth rate, while natural capital and per capita health spending lead to a smaller increase in GDP per capita.

The above results mean the following:

The education of the population over 25 years of age, with secondary–tertiary education having the greatest impact on per capita productivity, shows that human capital is the most critical factor for increasing per capita productivity. In other words, we would say that in the BRICS countries, investment in knowledge and skills seems to pay off more than the other factors in the model.

Population growth (especially in the working age) creates a demographic advantage and therefore enhances productive and economic growth. However, the positive result assumes that the educational and economic systems can absorb the growing population.

Physical capital (investments in infrastructure, machinery, technology) remains important in increasing productivity, but its efficiency seems lower than that of human capital. This is consistent with the theory of endogenous growth, where knowledge and education “multiply” the efficiency of physical capital.

Per capita health spending is in fourth place among the factors affecting per capita productivity, but it is an important factor because better health increases labor productivity and reduces absenteeism/illness costs. Therefore, it plays a complementary role because a healthy workforce means better utilization of education and capital.

This result is consistent with the results of the work by

Hatam et al. (

2016), who examined the relationship between health spending and economic growth for the Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO) countries, and by

Ozyilmaz et al. (

2022), who investigated the effect of health spending on economic growth in the 27 EU countries.

The estimation of the short-run results of the ARDL(1,1,1,1,1) cointegration model in

Table 8 shows that the variables of natural capital and the average level of education for people over 25 years old do not seem to affect GDP per capita in the BRICS countries in the short run. Conversely, per capita health spending has a positive effect on per capita GDP, while the population growth rate has a negative effect on per capita GDP.

The results of the short-run estimation mean the following:

Natural capital and education over 25 years are not statistically significant in the short run because of the following:

These factors take time to pay off.

Increased capital investment or higher levels of education do not translate directly into higher productivity; they are structural factors with long-term effects.

Essentially, the model shows that the BRICS countries benefit from education and capital in the long run but not in the short run.

The positive effect of per capita health spending in the short run shows the following:

Investments in health have an immediate effect on productivity. Better health means more productive workers, less absenteeism, and higher energy levels.

Furthermore, this “quick effect” explains why the health variable appears significant in the short-term relationship.

The negative impact of population growth on productivity means the following:

Rapid population growth in the BRICS countries may, in the short term, put pressure on increased needs for infrastructure, education, health, and labor.

When the economy does not sufficiently absorb the new population, this leads to unemployment or underemployment, reducing per capita production.

Therefore, the positive demographic impulse is only felt in the medium to long term if it is accompanied by investments in human capital.

This result coincides with the relationship between economic growth and health spending found by

Qehaja et al. (

2023) for the Western Balkan countries.

8. Conclusions and Policy Implications

This study investigates the relationship between per capita health expenditure, education, natural capital, population growth, and per capita GDP in the BRICS countries for the period 2000–2021, using a dynamic panel ARDL framework. Diagnostic tests confirmed cross-sectional dependence and slope heterogeneity, necessitating second-generation unit root and cointegration techniques. The long-run results indicate that all variables significantly influence GDP per capita, with education and population growth exerting the strongest positive effects, followed by natural capital and health expenditure. In the short run, health spending is consistently positive across several countries, while the effects of education, natural capital, and demographics vary considerably by context. For example, health spending drives growth in Brazil, China, India, and South Africa, whereas natural capital contributes positively in China, Egypt, and Ethiopia but negatively in Russia and Saudi Arabia. Education and population dynamics often display delayed or mixed effects, highlighting structural differences among countries.

The findings of this study also point to several directions for future research. The differentiated short- and long-run effects observed across the BRICS economies highlight the need to examine how institutional quality, health system efficiency, and governance structures mediate the growth impact of health spending. Further work could also explore the interaction between health expenditure, education, and demographic trends, given their central role in human capital formation. Additionally, the varying influence of natural capital across countries suggests that environmental conditions and resource dependence may shape the health–growth nexus more strongly than previously recognized. Incorporating these dimensions into more detailed country-specific or sectoral analyses would improve our understanding of the mechanisms through which health investment contributes to long-run economic performance.

Overall, the findings suggest that the qualitative dimensions of human capital—particularly education and health—are more decisive for long-term growth in the BRICS countries than the simple accumulation of physical capital. Demographics can serve as an additional engine of growth if coupled with improved skills. The policy implication is that the BRICS economies should prioritize investment in health, education, and human capital development, as these not only enhance well-being but also reinforce productivity, natural capital utilization, and sustainable economic growth.