Statistical Quantification of the COVID-19 Pandemic’s Continuing Lingering Effect on Economic Losses in the Tourism Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction and Literature Review

- (i)

- The three studies did not provide the estimated loss of tourist arrivals in the post-intervention period;

- (ii)

- The selected pre-intervention period in the three studies is inconsistent with the exact timeframe (March 2020) in which lockdown was introduced in RSA;

- (iii)

- The different types of outliers were not detected in the three studies and incorporated within the pre-intervention model in order to improve its overall fit and accuracy;

- (iv)

- The three studies used basic SARIMA models without incorporating any intervention variables to capture the effect of COVID-19 during the post-intervention period, meaning that we may quantify the exact economic losses due to the sustained negative effect (or lingering effect) of the COVID-19 pandemic since March 2020 when the first strict lockdown was implemented in the RSA.

- (RQ1)

- Is the SARIMAX (instead of the SARIMA) intervention model appropriate for quantifying the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on tourist arrivals?

- (RQ2)

- What are estimated total losses in the number of tourist arrivals due to COVID-19?

- (RQ3)

- Did the number of tourist arrivals recover to its pre-COVID-19 levels?

- (RQ4)

- What is the possible future outlook for tourist arrivals?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. SARIMA Model

2.2. Additive and Innovative Outliers

2.3. SARIMAX Intervention Model

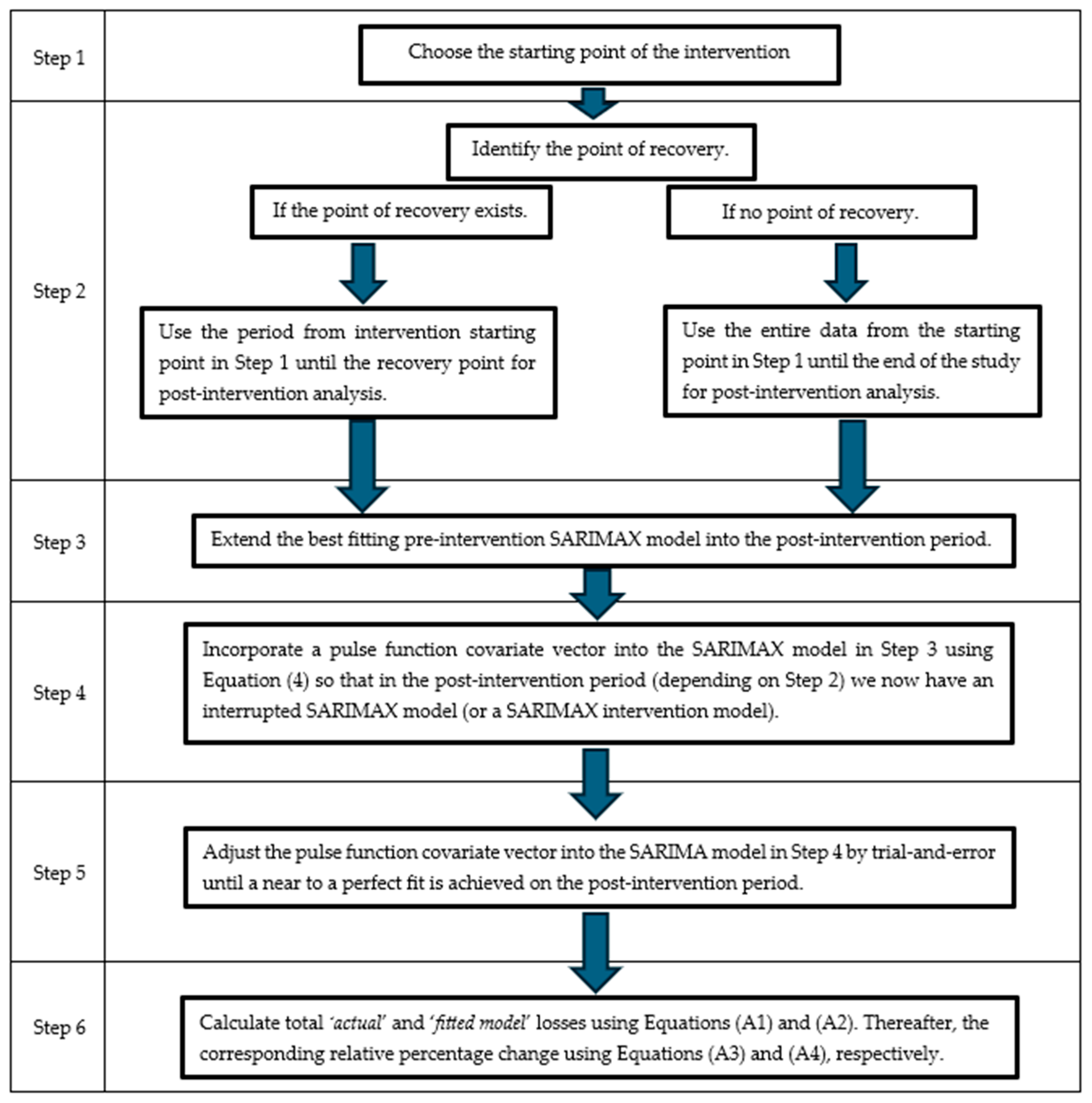

- Step 1:

- Choose the starting point of the intervention.

- Step 2:

- Identify the point of recovery.

- Step 3:

- Extend the best-fitting pre-intervention SARIMA model into the post-intervention period.

- Step 4:

- Supplement the SARIMA model in Step 3 with the pulse function covariate vector fitted via trial and error to make it a SARIMAX intervention model.

- Step 5:

- Adjust the components of the pulse function covariate vector one by one starting from the starting point of the intervention in Step 1 to the recovery point or the end of the dataset if there is no recovery point. The aim is to select components of the pulse function covariate vector that produce fitted values that are as close as possible to the actual interrupted series in the post-intervention period. An ideal model will have the lowest mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) and the root mean squared error (RMSE) values (Moreno et al., 2013).

- Step 6:

- The SARIMAX intervention model in Step 4 and Step 5 is then used to calculate estimated losses in the intervention period.

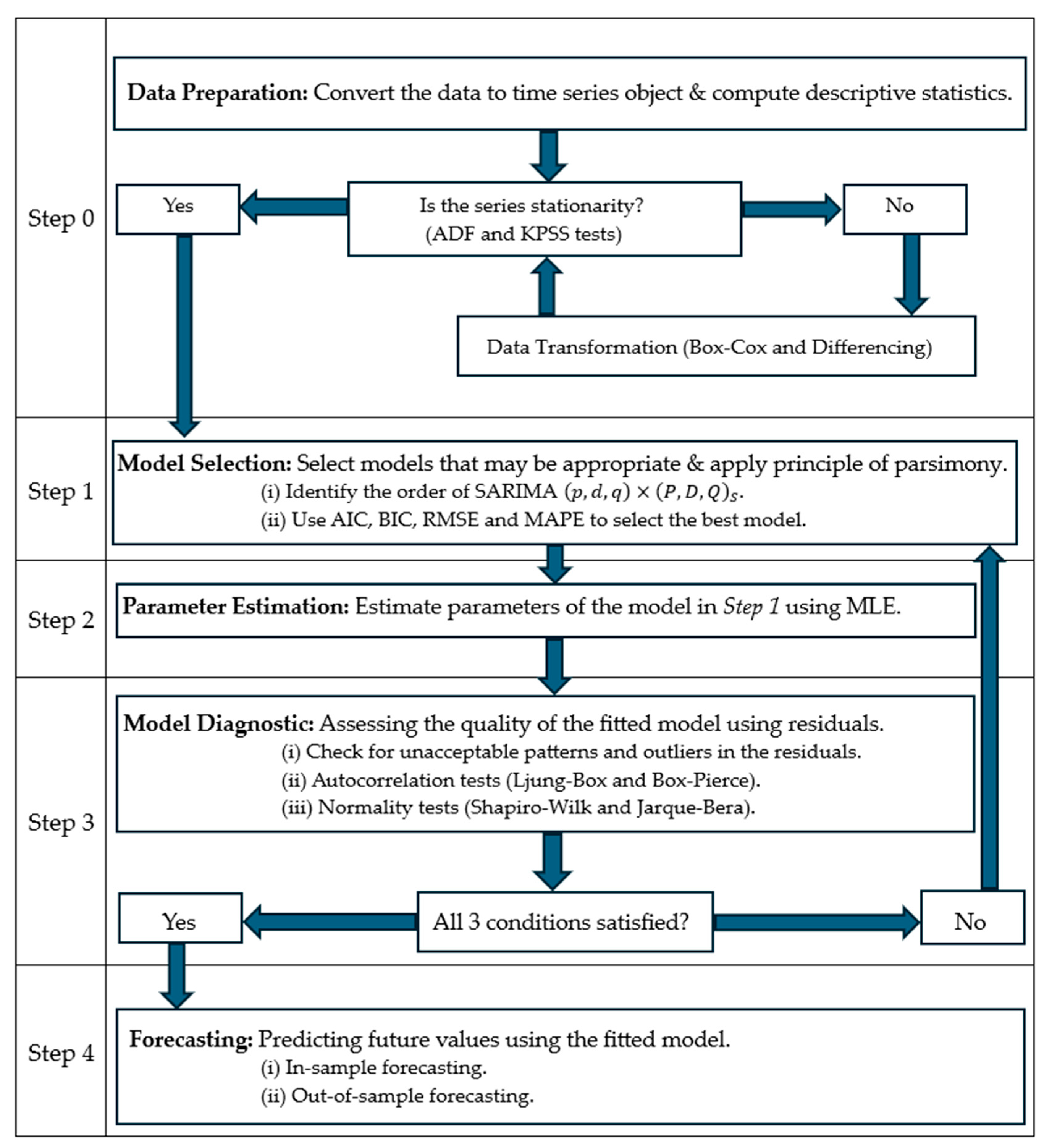

2.4. Data Preparation and Stationarity

2.5. Model Specification and Accuracy

2.6. Parameter Estimation

2.7. Model Diagnostics

2.8. R Packages

3. Analysis and Results

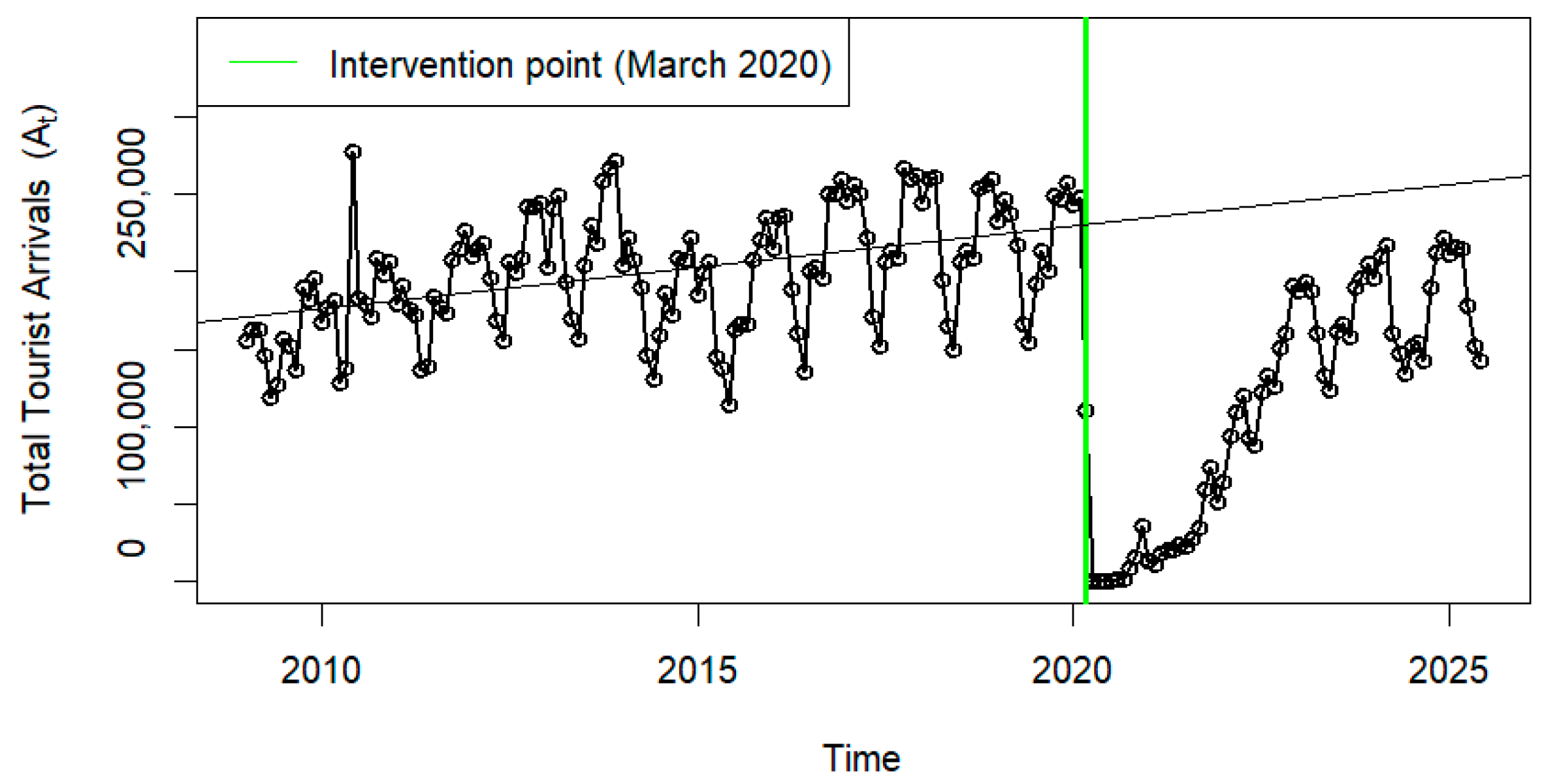

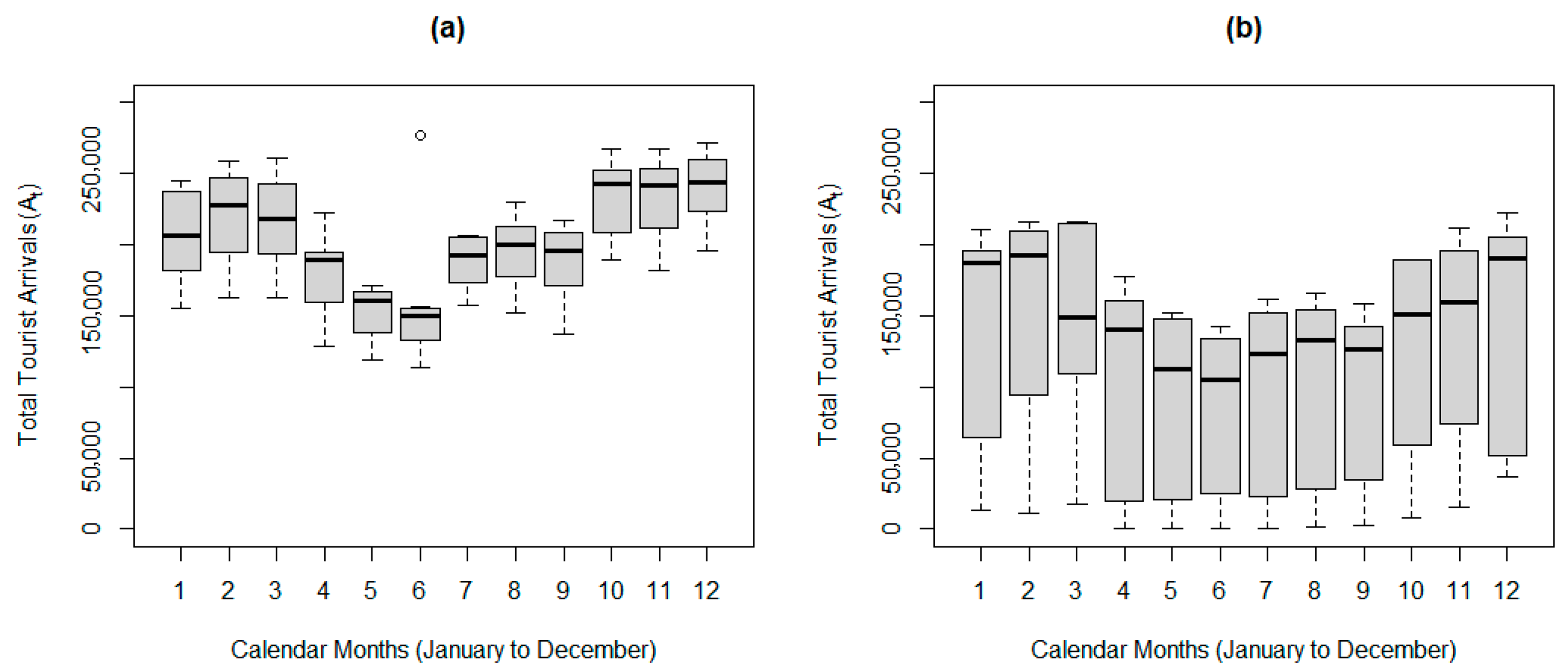

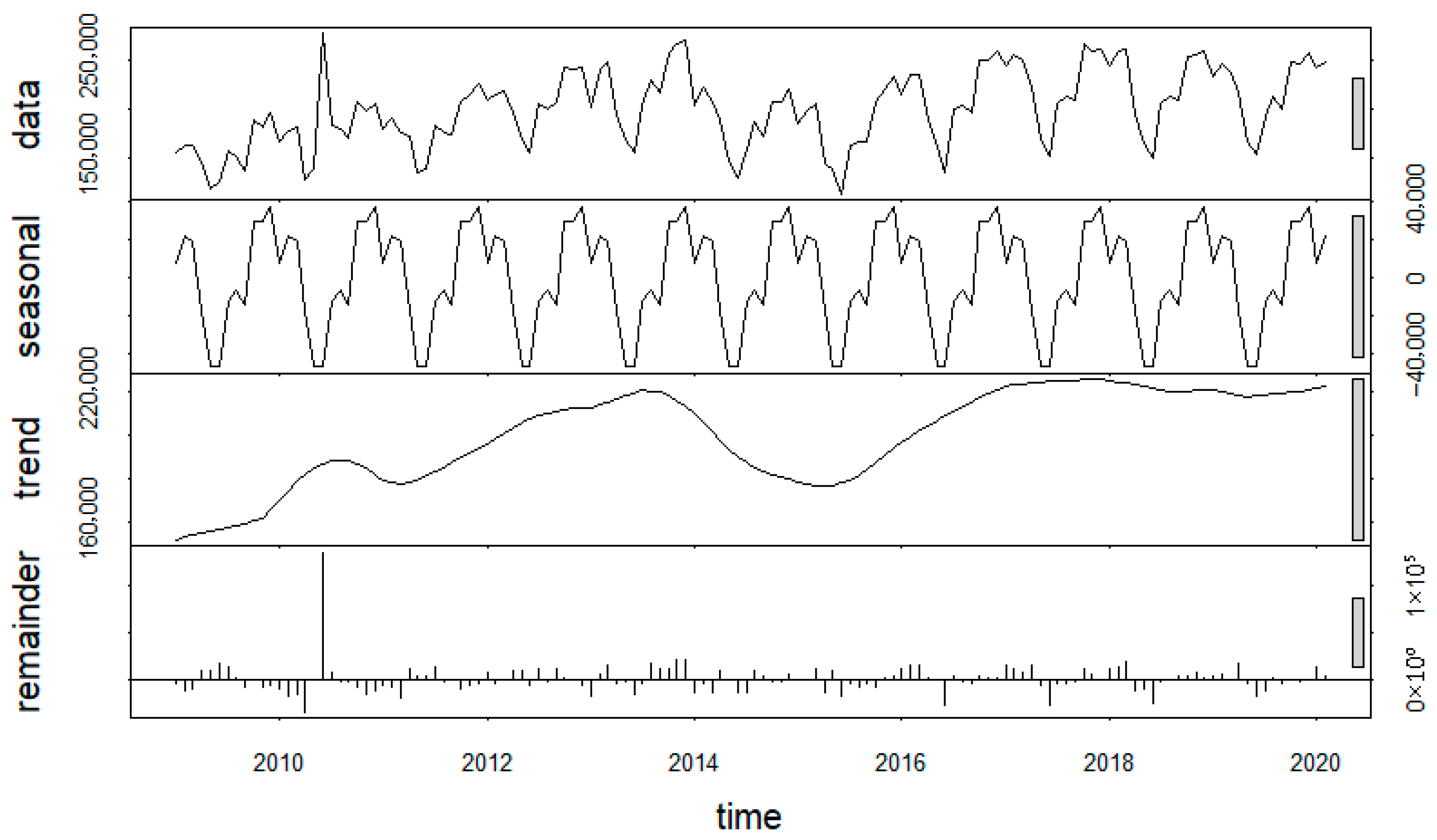

3.1. Data Overview

3.2. Pre-Intervention Analysis

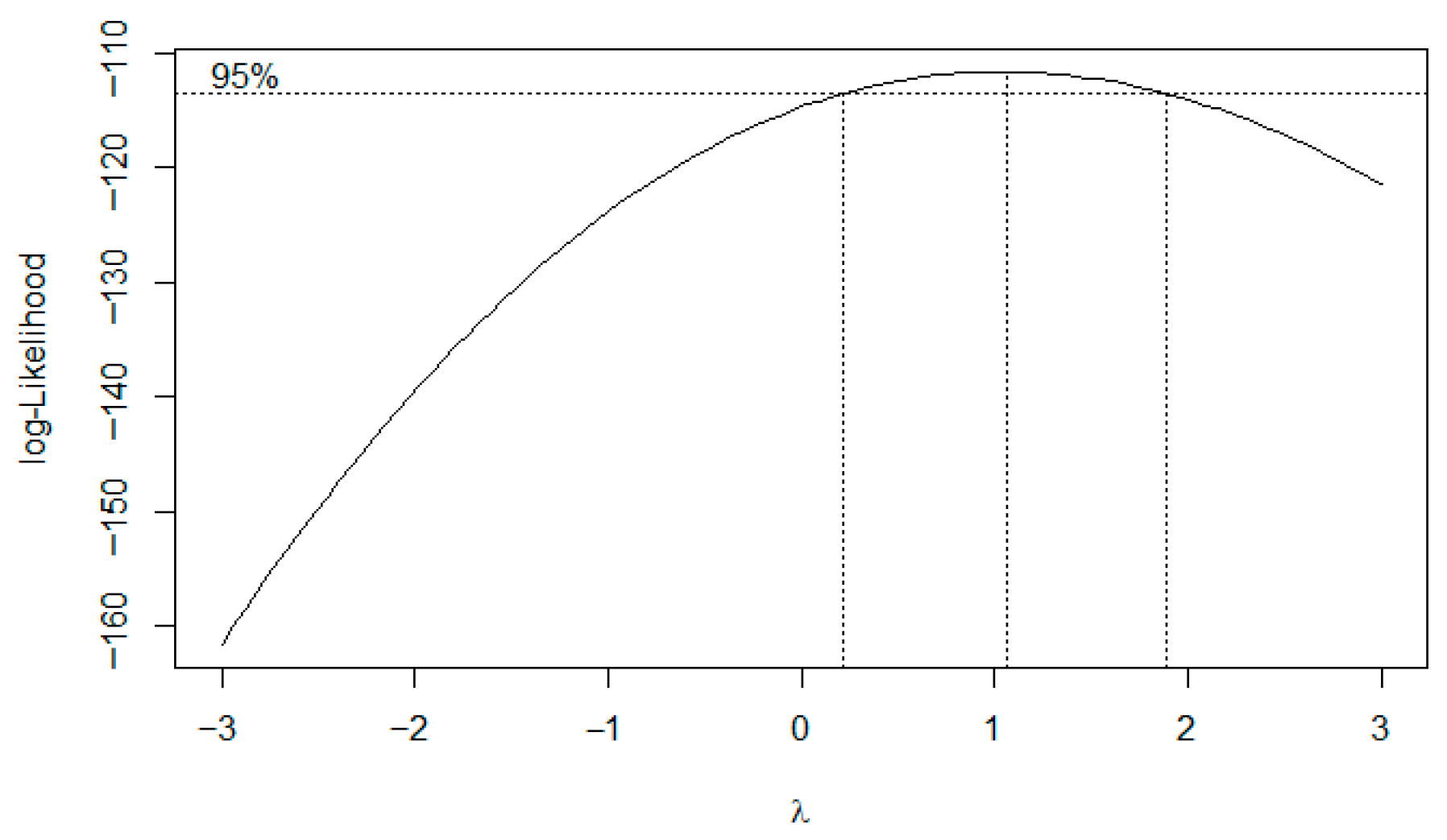

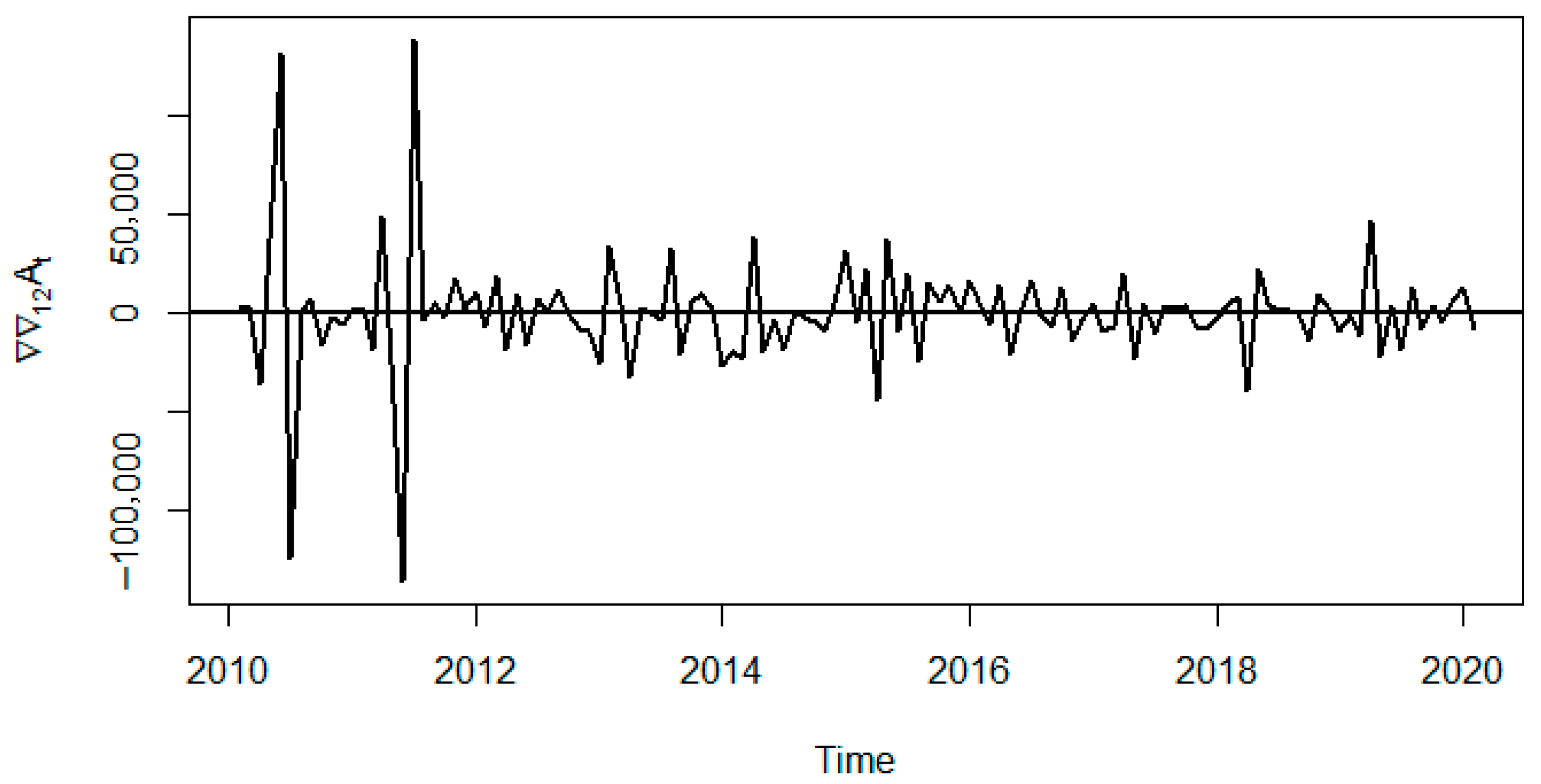

3.3. Data Transformation

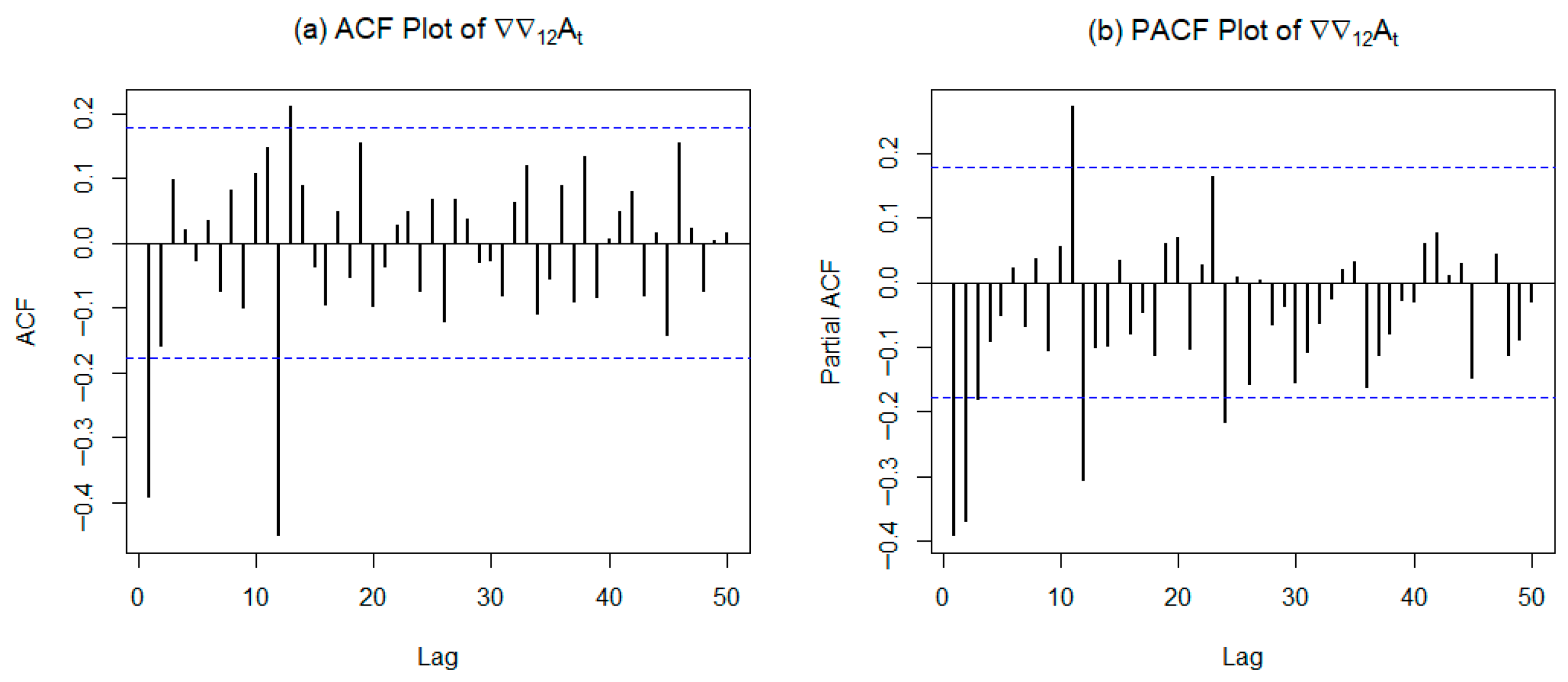

3.4. Model Specification

3.5. Parameter Estimation

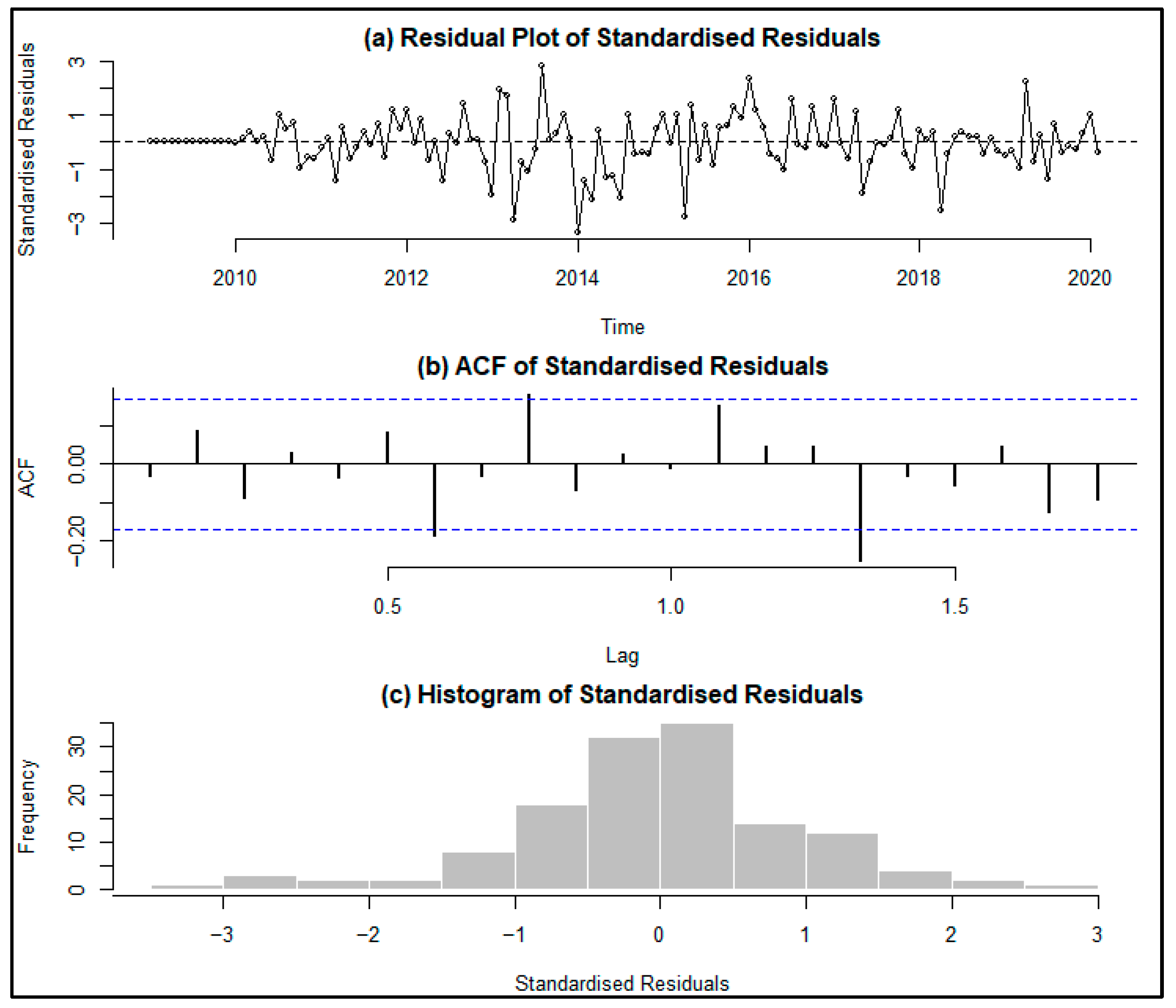

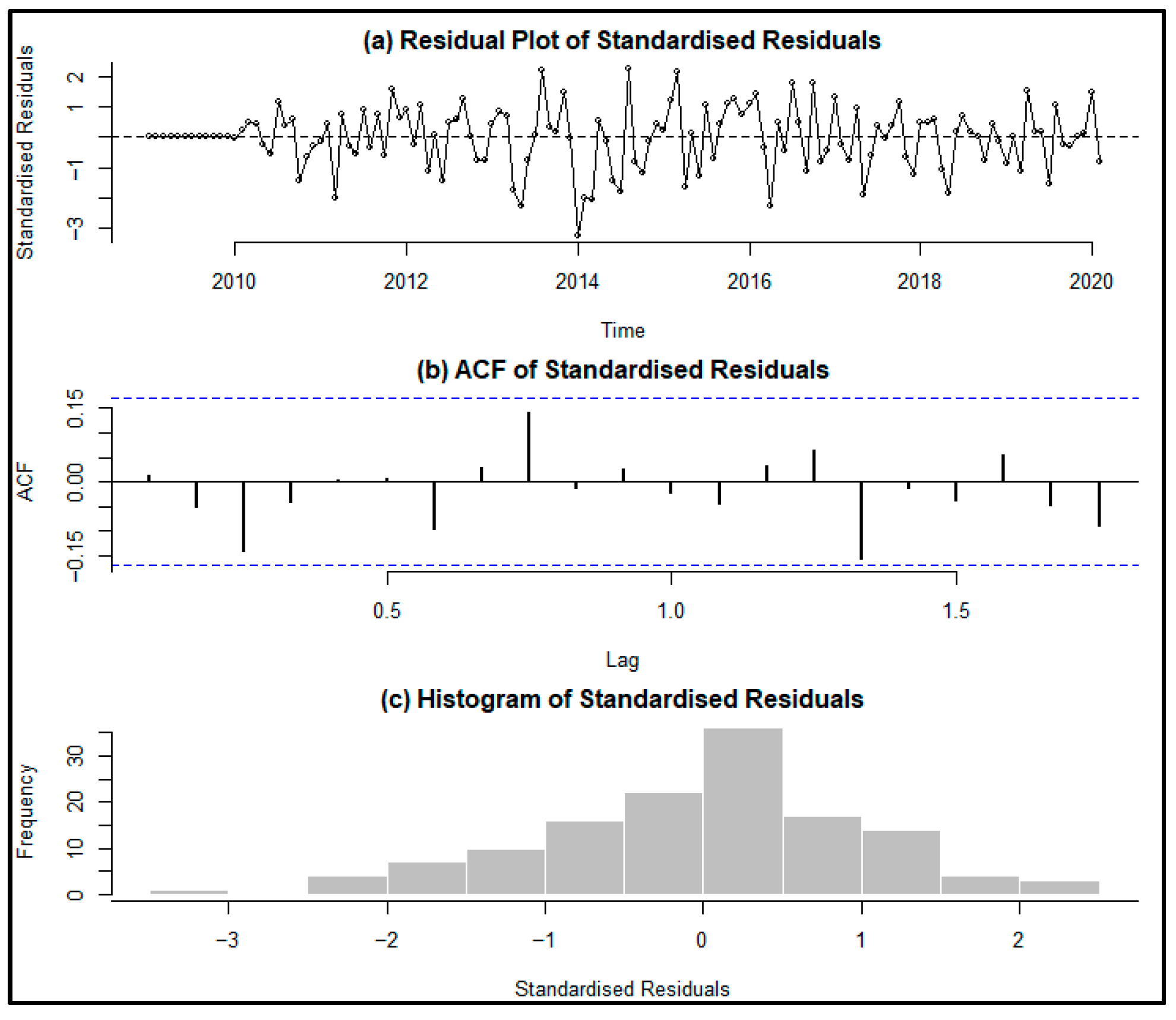

3.6. Residual Analysis

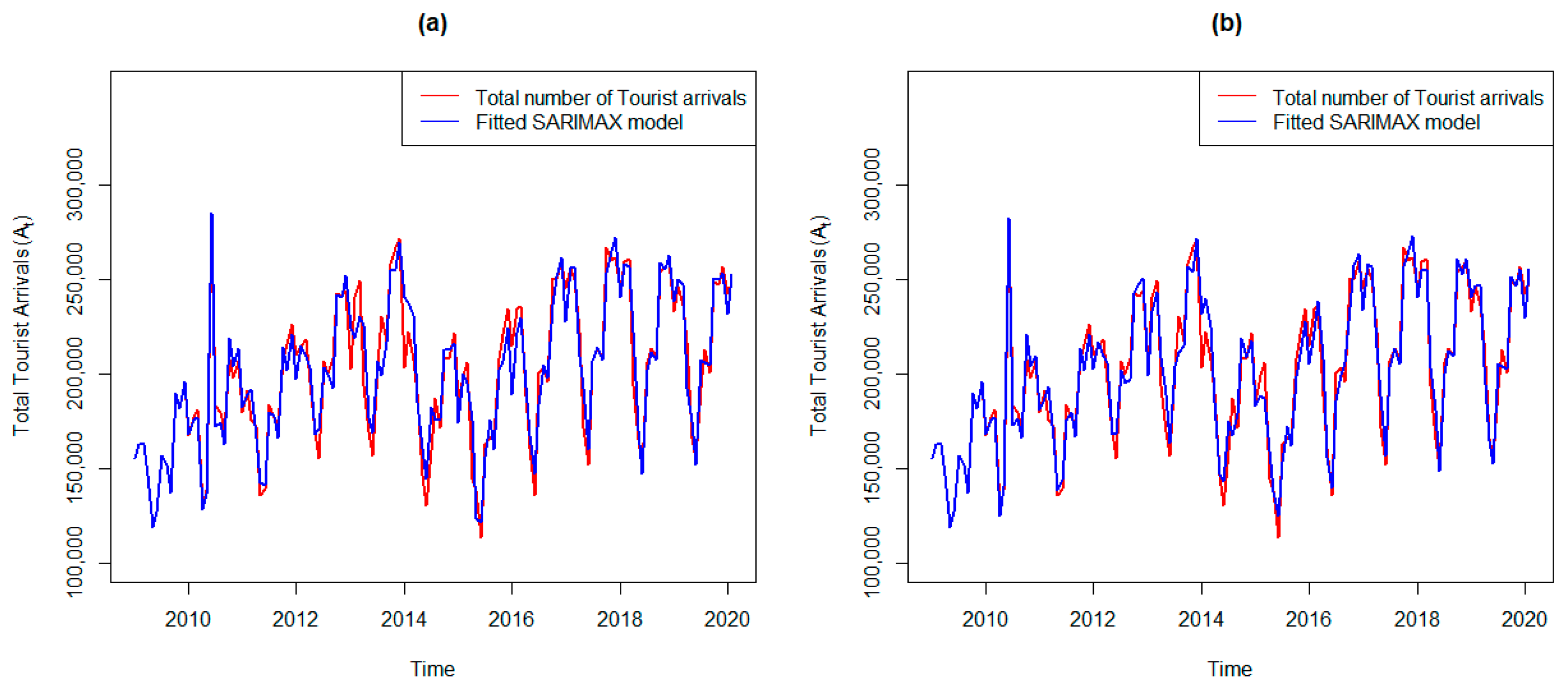

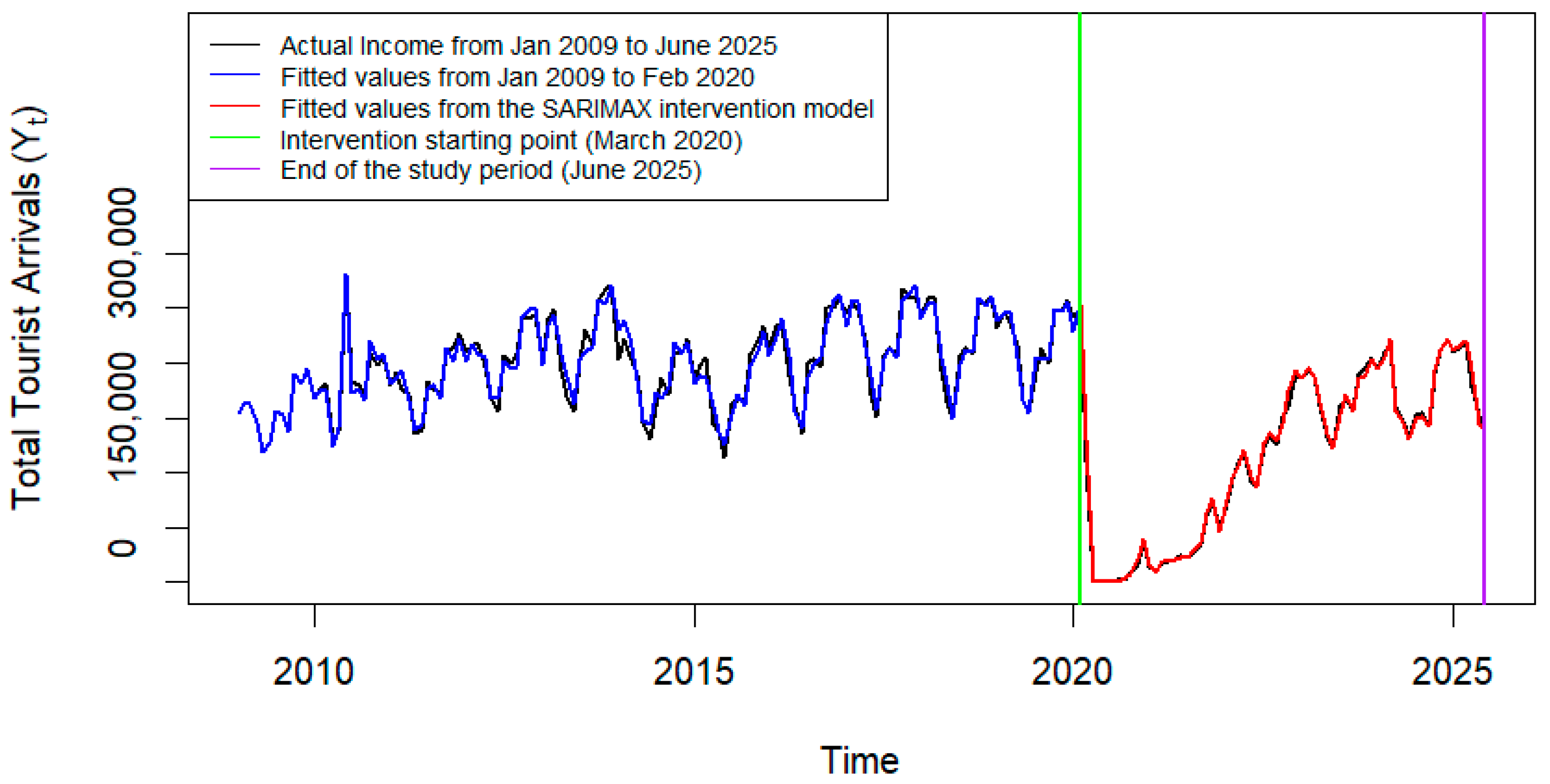

3.7. Actual Data in Comparison with Fitted Values

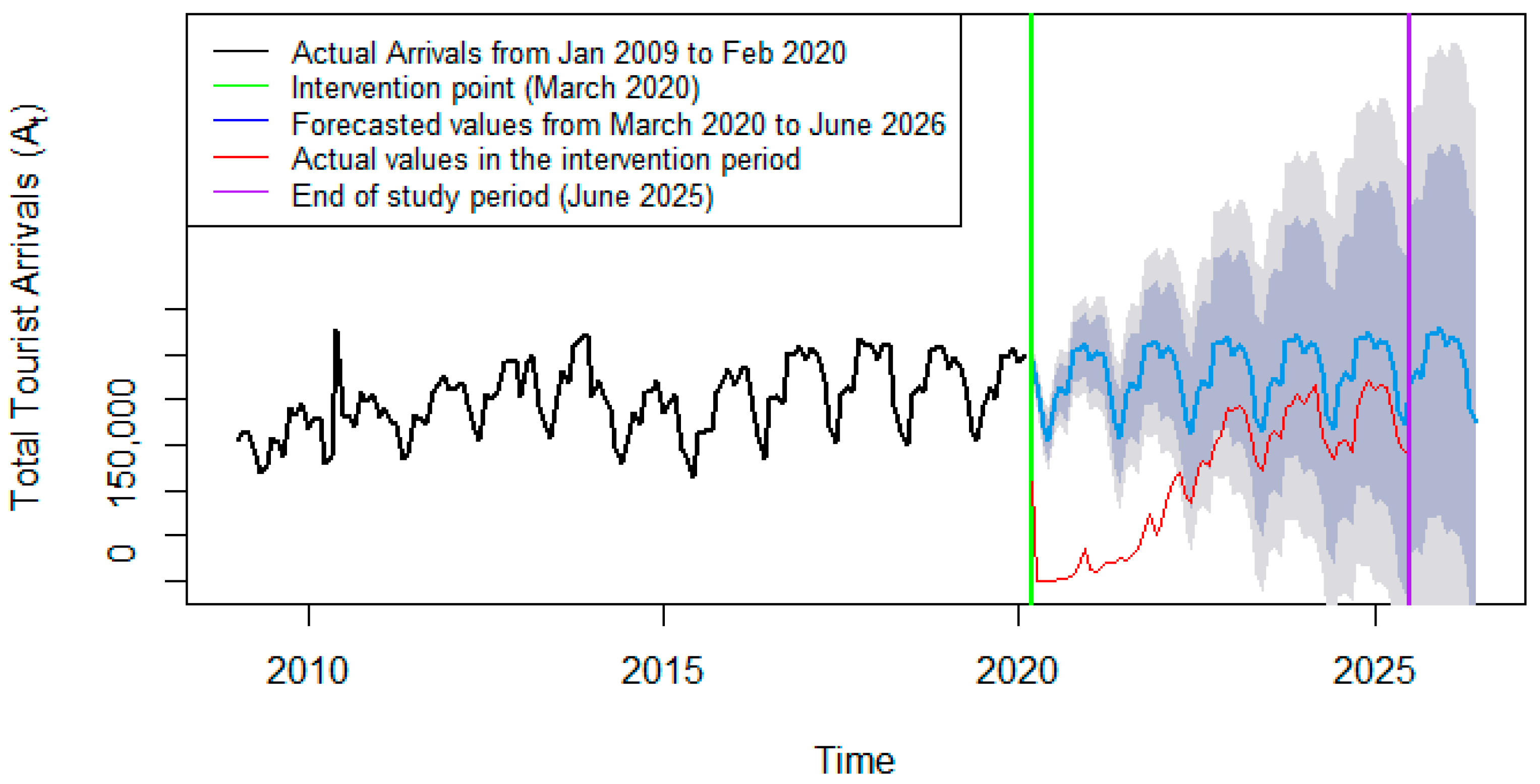

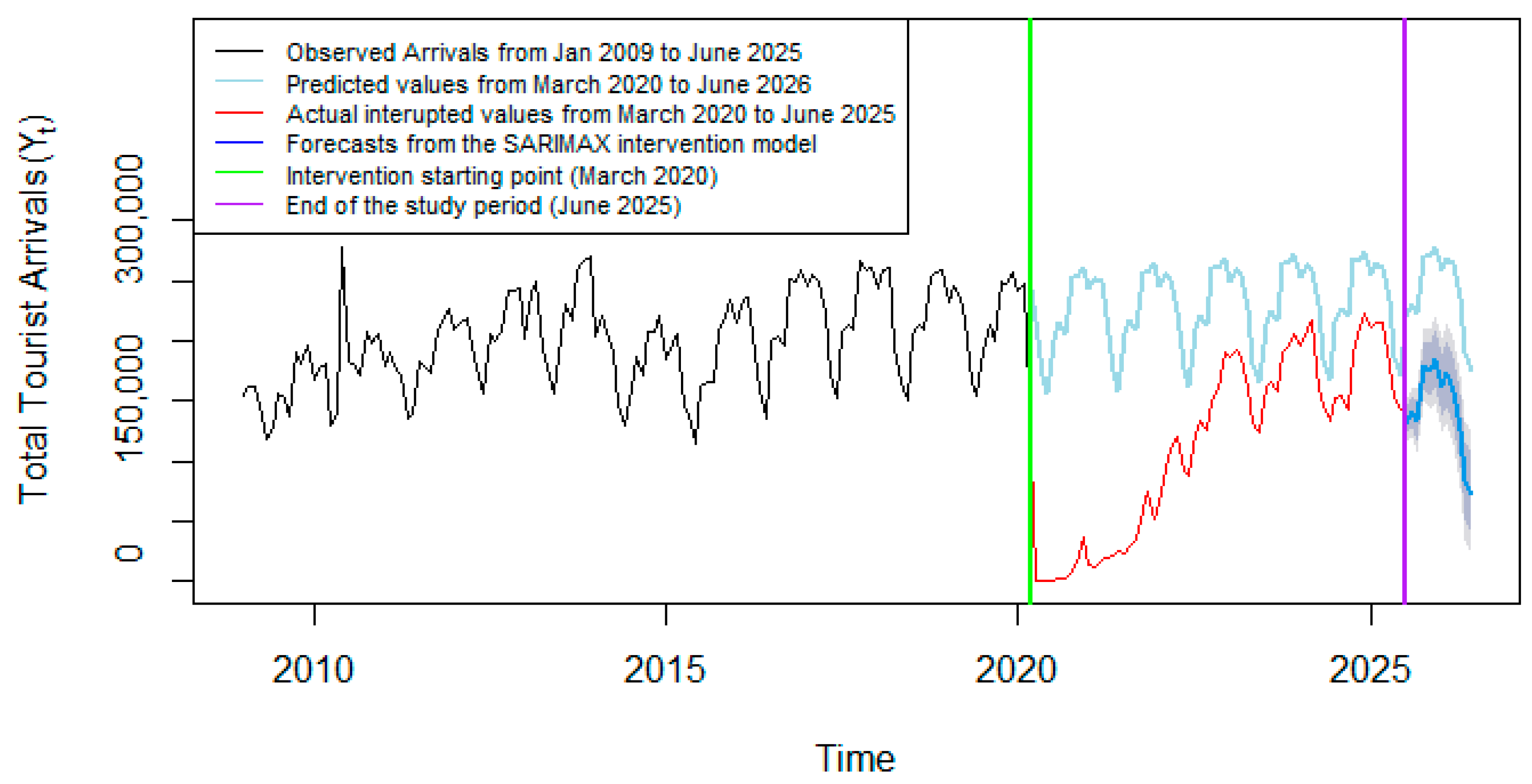

3.8. Forecasting

3.9. Post-Intervention Analysis

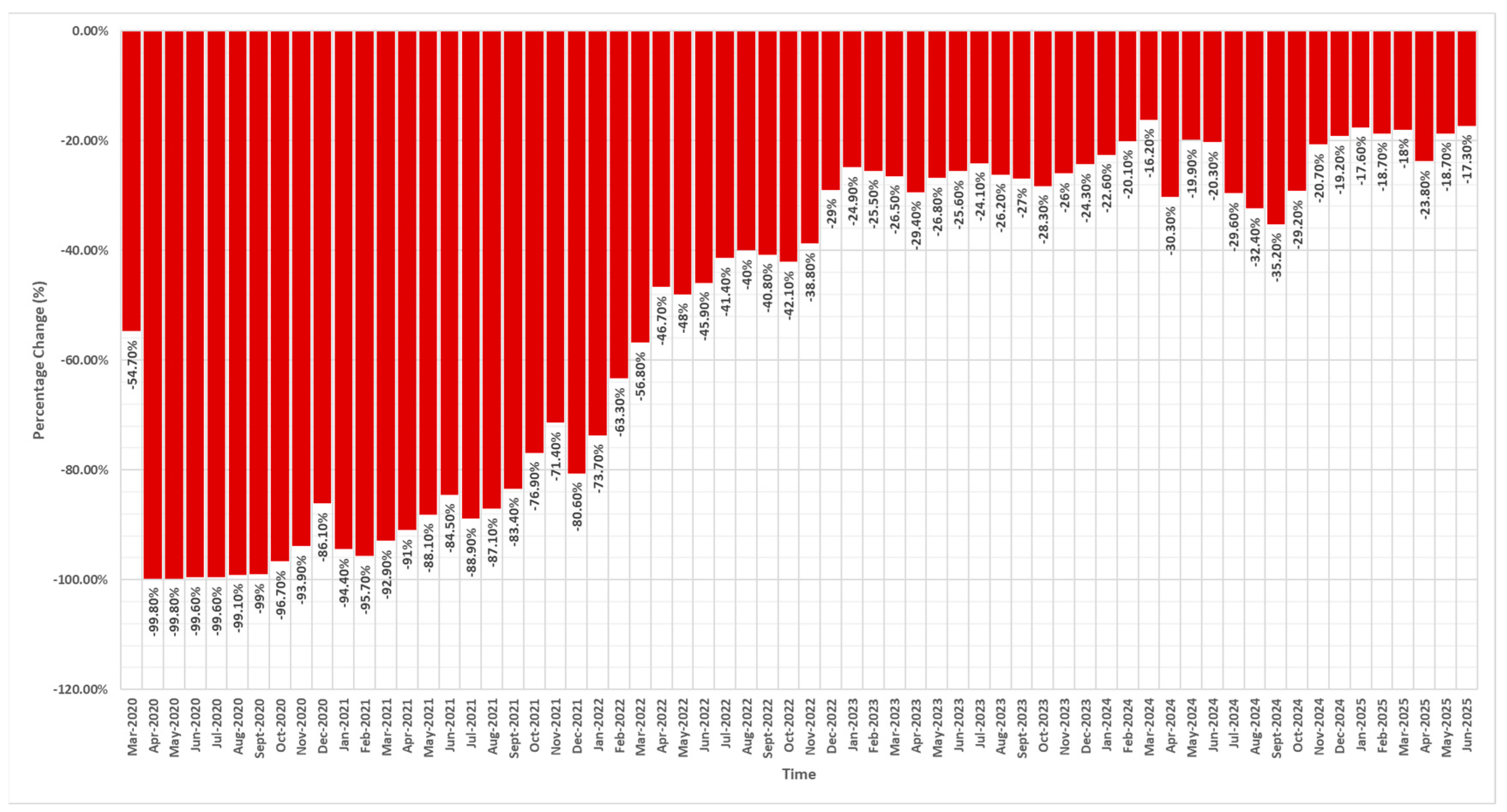

3.10. Quantification of Pandemic Effects

4. Discussion of Research Questions

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACF | Autocorrelation Function |

| AIC | Akaike’s Information Criterion |

| AO | Additive Outlier |

| ARIMA | Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| IO | Innovative Outlier |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| PACF | Partial Autocorrelation Function |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| RSA | Republic of South Africa |

| SARIMA | Seasonal Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average |

| SARIMAX | Seasonal Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average with exogenous variables |

Appendix A. Dataset

| January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 155,228 | 162,714 | 162,562 | 146,504 | 118,718 | 126,857 | 156,846 | 152,187 | 136,767 | 189,932 | 181,923 | 195,739 |

| 2010 | 167,706 | 177,165 | 181,125 | 128,773 | 138,261 | 277,345 | 183,042 | 179,658 | 171,158 | 208,276 | 197,930 | 206,555 |

| 2011 | 179,493 | 190,865 | 175,876 | 172,145 | 135,922 | 139,063 | 183,426 | 176,696 | 173,497 | 208,141 | 215,235 | 226,360 |

| 2012 | 210,254 | 214,594 | 218,436 | 195,934 | 168,796 | 155,464 | 206,656 | 199,820 | 208,203 | 242,475 | 241,413 | 243,718 |

| 2013 | 202,548 | 240,387 | 249,009 | 193,848 | 169,376 | 156,563 | 204,120 | 230,374 | 217,645 | 258,380 | 266,946 | 271,435 |

| 2014 | 203,604 | 221,945 | 207,093 | 189,943 | 146,342 | 130,410 | 159,368 | 186,801 | 171,791 | 208,263 | 207,801 | 221,348 |

| 2015 | 184,864 | 199,029 | 205,909 | 144,771 | 138,258 | 113,689 | 162,733 | 165,990 | 166,053 | 208,020 | 221,149 | 234,523 |

| 2016 | 214,903 | 234,707 | 235,640 | 188,491 | 160,627 | 135,780 | 200,901 | 203,421 | 196,098 | 250,737 | 250,017 | 259,724 |

| 2017 | 245,074 | 255,901 | 249,641 | 222,055 | 171,417 | 151,736 | 206,737 | 213,294 | 208,720 | 267,025 | 259,805 | 261,728 |

| 2018 | 244,657 | 259,123 | 260,514 | 194,017 | 165,137 | 149,791 | 206,076 | 213,761 | 209,185 | 253,945 | 256,537 | 259,403 |

| 2019 | 232,872 | 246,394 | 236,647 | 217,131 | 166,227 | 154,361 | 192,277 | 213,074 | 200,571 | 248,673 | 247,136 | 256,796 |

| 2020 | 242,550 | 248,037 | 110,241 | 507 | 315 | 549 | 873 | 1950 | 2084 | 8325 | 15,520 | 36,357 |

| 2021 | 13,687 | 10,745 | 17,548 | 19,915 | 20,762 | 24,548 | 22,877 | 28,157 | 34,895 | 59,475 | 73,679 | 51,516 |

| 2022 | 64,714 | 93,899 | 108,974 | 119,518 | 92,368 | 87,685 | 122,720 | 132,757 | 126,409 | 151,189 | 159,771 | 190,667 |

| 2023 | 187,189 | 192,835 | 187,631 | 160,647 | 132,443 | 123,069 | 161,376 | 165,705 | 158,407 | 189,778 | 195,549 | 205,684 |

| 2024 | 195,423 | 209,545 | 216,563 | 160,708 | 147,428 | 134,396 | 152,082 | 153,913 | 142,510 | 189,575 | 212,335 | 222,163 |

| 2025 | 210,709 | 215,830 | 214,546 | 178,195 | 152,398 | 142,068 |

Appendix B. Quantification of COVID-19 Pandemic’s Lingering Effect

| Actual vs. Predicted Values | Fitted vs. Predicted Values | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postintervention Period | Predicted Values per Month, | Actual Values per Month, | Actual Losses per Month, () | % Change, | Covariate Vector | Fitted Values per Month, | Estimated Losses per Month, () | % Change, |

| Mar-2020 | 243,383 | 110,241 | −133,142 | −54.70% | 0.95 | 130,061 | −113,322 | −46.60% |

| Apr-2020 | 217,562 | 507 | −217,055 | −99.80% | 1.7 | 795 | −216,767 | −99.60% |

| May-2020 | 171,169 | 315 | −170,854 | −99.80% | 1.3 | 140 | −171,029 | −99.90% |

| Jun-2020 | 155,996 | 549 | −155,447 | −99.60% | 1.2 | 258 | −155,738 | −99.80% |

| Jul-2020 | 200,858 | 873 | −199,985 | −99.60% | 1.55 | 508 | −200,350 | −99.70% |

| Aug-2020 | 214,702 | 1950 | −212,752 | −99.10% | 1.68 | 705 | −213,997 | −99.70% |

| Sept-2020 | 206,076 | 2084 | −203,992 | −99% | 1.58 | 3460 | −202,616 | −98.30% |

| Oct-2020 | 253,913 | 8325 | −245,588 | −96.70% | 1.95 | 7458 | −246,455 | −97.10% |

| Nov-2020 | 253,361 | 15,520 | −237,841 | −93.90% | 1.83 | 20,254 | −233,107 | −92% |

| Dec-2020 | 261,391 | 36,357 | −225,034 | −86.10% | 1.72 | 39,119 | −222,272 | −85% |

| Jan-2021 | 243,874 | 13,687 | −230,187 | −94.40% | 1.73 | 16,401 | −227,473 | −93.30% |

| Feb-2021 | 252,317 | 10,745 | −241,572 | −95.70% | 1.85 | 9067 | −243,250 | −96.40% |

| Mar-2021 | 248,885 | 17,548 | −231,337 | −92.90% | 1.65 | 18,659 | −230,227 | −92.50% |

| Apr-2021 | 220,832 | 19,915 | −200,917 | −91% | 1.43 | 19,583 | −201,250 | −91.10% |

| May-2021 | 174,536 | 20,762 | −153,774 | −88.10% | 1.02 | 21,338 | −153,198 | −87.80% |

| Jun-2021 | 158,861 | 24,548 | −134,313 | −84.50% | 0.9 | 22,807 | −136,054 | −85.60% |

| Jul-2021 | 206,267 | 22,877 | −183,390 | −88.90% | 1.3 | 22,018 | −184,249 | −89.30% |

| Aug-2021 | 217,899 | 28,157 | −189,742 | −87.10% | 1.35 | 29,659 | −188,240 | −86.40% |

| Sept-2021 | 210,437 | 34,895 | −175,542 | −83.40% | 1.2 | 36,705 | −173,732 | −82.60% |

| Oct-2021 | 258,012 | 59,475 | −198,537 | −76.90% | 1.38 | 62,570 | −195,442 | −75.70% |

| Nov-2021 | 257,937 | 73,679 | −184,258 | −71.40% | 1.2 | 77,209 | −180,728 | −70.10% |

| Dec-2021 | 265,332 | 51,516 | −213,816 | −80.60% | 1.5 | 46,127 | −219,205 | −82.60% |

| Jan-2022 | 245,970 | 64,714 | −181,256 | −73.70% | 1.15 | 68,900 | −177,069 | −72% |

| Feb-2022 | 255,719 | 93,899 | −161,820 | −63.30% | 1 | 96,050 | −159,669 | −62.40% |

| Mar-2022 | 251,981 | 108,974 | −143,007 | −56.80% | 0.8 | 105,305 | −146,676 | −58.20% |

| Apr-2022 | 224,180 | 119,518 | −104,662 | −46.70% | 0.5 | 120,010 | −104,170 | −46.50% |

| May-2022 | 177,676 | 92,368 | −85,308 | −48% | 0.3 | 96,408 | −81,268 | −45.70% |

| Jun-2022 | 162,172 | 87,685 | −74,487 | −45.90% | 0.25 | 87,045 | −75,127 | −46.30% |

| Jul-2022 | 209,437 | 122,720 | −86,717 | −41.40% | 0.3 | 127,028 | −82,409 | −39.30% |

| Aug-2022 | 221,186 | 132,757 | −88,429 | −40% | 0.3 | 135,045 | −86,141 | −38.90% |

| Sept-2022 | 213,628 | 126,409 | −87,219 | −40.80% | 0.25 | 128,452 | −85,176 | −39.90% |

| Oct-2022 | 261,282 | 151,189 | −110,093 | −42.10% | 0.5 | 144,269 | −117,013 | −44.80% |

| Nov-2022 | 261,142 | 159,771 | −101,371 | −38.80% | 0.25 | 174,739 | −86,403 | −33.10% |

| Dec-2022 | 268,591 | 190,667 | −77,924 | −29% | 0.1 | 192,720 | −75,871 | −28.20% |

| Jan-2023 | 249,184 | 187,189 | −61,995 | −24.90% | −0.1 | 186,304 | −62,880 | −25.20% |

| Feb-2023 | 258,970 | 192,835 | −66,135 | −25.50% | −0.05 | 194,592 | −64,378 | −24.90% |

| Mar-2023 | 255,202 | 187,631 | −67,571 | −26.50% | −0.1 | 187,827 | −67,375 | −26.40% |

| Apr-2023 | 227,426 | 160,647 | −66,779 | −29.40% | −0.1 | 163,842 | −63,584 | −28% |

| May-2023 | 180,901 | 132,443 | −48,458 | −26.80% | −0.3 | 135,005 | −45,896 | −25.40% |

| Jun-2023 | 165,414 | 123,069 | −42,345 | −25.60% | −0.3 | 121,567 | −43,847 | −26.50% |

| Jul-2023 | 212,665 | 161,376 | −51,289 | −24.10% | −0.2 | 153,340 | −59,326 | −27.90% |

| Aug-2023 | 224,425 | 165,705 | −58,720 | −26.20% | −0.2 | 171,632 | −52,793 | −23.50% |

| Sept-2023 | 216,858 | 158,407 | −58,451 | −27% | −0.2 | 156,528 | −60,330 | −27.80% |

| Oct-2023 | 264,520 | 189,778 | −74,742 | −28.30% | −0.02 | 187,222 | −77,298 | −29.20% |

| Nov-2023 | 264,373 | 195,549 | −68,824 | −26% | −0.1 | 187,338 | −77,035 | −29.10% |

| Dec-2023 | 271,828 | 205,684 | −66,144 | −24.30% | −0.1 | 204,217 | −67,611 | −24.90% |

| Jan-2024 | 252,416 | 195,423 | −56,993 | −22.60% | −0.2 | 194,246 | −58,170 | −23% |

| Feb-2024 | 262,206 | 209,545 | −52,661 | −20.10% | −0.2 | 205,283 | −56,923 | −21.70% |

| Mar-2024 | 258,435 | 216,563 | −41,872 | −16.20% | −0.4 | 222,914 | −35,521 | −13.70% |

| Apr-2024 | 230,661 | 160,708 | −69,953 | −30.30% | −0.1 | 155,353 | −75,308 | −32.60% |

| May-2024 | 184,135 | 147,428 | −36,707 | −19.90% | −0.4 | 145,545 | −38,590 | −21% |

| Jun-2024 | 168,649 | 134,396 | −34,253 | −20.30% | −0.35 | 131,455 | −37,194 | −22.10% |

| Jul-2024 | 215,899 | 152,082 | −63,817 | −29.60% | −0.08 | 149,650 | −66,249 | −30.70% |

| Aug-2024 | 227,660 | 153,913 | −73,747 | −32.40% | −0.01 | 151,704 | −75,956 | −33.40% |

| Sept-2024 | 220,092 | 142,510 | −77,582 | −35.20% | 0.01 | 142,707 | −77,385 | −35.20% |

| Oct-2024 | 267,754 | 189,575 | −78,179 | −29.20% | 0.01 | 193,455 | −74,300 | −27.70% |

| Nov-2024 | 267,607 | 212,335 | −55,272 | −20.70% | −0.2 | 211,108 | −56,499 | −21.10% |

| Dec-2024 | 275,062 | 222,163 | −52,899 | −19.20% | −0.2 | 221,976 | −53,086 | −19.30% |

| Jan-2025 | 255,650 | 210,709 | −44,941 | −17.60% | −0.3 | 211,464 | −44,186 | −17.30% |

| Feb-2025 | 265,441 | 215,830 | −49,611 | −18.70% | −0.25 | 217,470 | −47,970 | −18.10% |

| Mar-2025 | 261,669 | 214,546 | −47,123 | −18% | −0.4 | 220,278 | −41,392 | −15.80% |

| Apr-2025 | 233,896 | 178,195 | −55,701 | −23.80% | −0.4 | 192,738 | −41,157 | −17.60% |

| May-2025 | 187,369 | 152,398 | −34,971 | −18.70% | −0.5 | 143,661 | −43,708 | −23.30% |

| Jun-2025 | 171,884 | 142,068 | −29,816 | −17.30% | −0.5 | 139,984 | −31,900 | −18.60% |

| Total | −7,328,919 | Total | −7,283,540 | |||||

Appendix C. Additional Equations

References

- Ahmar, A. S., Guritno, S., Rahman, A., Minggi, I., Tiro, M. A., Aidid, M. K., Annas, S., Sutiksno, D. U., Ahmar, D. S., Ahmar, K. H., & Ahmar, A. A. (2018). Modeling data containing outliers using ARIMA additive outlier (ARIMA-AO). Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 954, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M. O., Khan, S., Haleem, A., Mansoor, H., Arshad, M. O., & Arshad, M. E. (2021). Understanding the impact of COVID-19 on Indian tourism sector through time series modelling. Journal of Tourism Futures, 9(1), 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D., Warrens, M. J., & Jurman, G. (2021). The coefficient of determination R-squared is more informative than SMAPE, MAE, MAPE, MSE and RMSE in regression analysis evaluation. PeerJ Computer Science, 7, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chipumuro, M., & Chikobvu, D. (2022). Modelling tourist arrivals in South Africa to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the tourism sector. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 11(4), 1381–1394. [Google Scholar]

- Chipumuro, M., Chikobvu, D., & Makoni, T. (2024a). A Time series approach to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the South African tourism sector. IntechOpen. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipumuro, M., Chikobvu, D., & Makoni, T. (2024b). Statistical analysis of overseas tourist arrivals to South Africa in assessing the impact of COVID-19 on sustainable development. Sustainability, 16, 5756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cryer, J. D., & Chan, K. (2008). Time series analysis with applications in R. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, M., Demir, Ş. Ş., Dalgıç, A., & Ergen, F. D. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the tourism industry: An evaluation from the hotel managers’ perspective. Journal of Tourism Theory and Research, 7(1), 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, R., Agrawal, A., Dhar, J., & Misra, A. K. (2024). Forecasting of Indian tourism industry using modeling approach. MethodsX, 12, 102723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujarati, D. N., & Porter, D. C. (2008). Basic econometrics (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill Irwin. [Google Scholar]

- Hamza, H. K., Bushra, B., & Yasmeen, N. Y. N. (2025). Examining the post-COVID-19 tourism recovery and resilience in the context of the African Tourism Industry. African Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 5(1), 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herranz, E. (2017). Unit root tests. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics, 9(3), e1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodson, T. O. (2022). Root mean square error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE): When to use them or not. Geoscientific Model Development Discussions, 15, 5481–5487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyndman, R. J., & Khandakar, Y. (2008). Automatic time series forecasting: The forecast package for R. Journal of Statistical Software, 27, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilo, S. O., Das, S., & Bello, F. G. (2023). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on South African tourism industry—A systematic review. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 12(2), 766–782. [Google Scholar]

- Janjua, L. R., Muhammad, F., & Rehman, A. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on logistics performance, economic growth and tourism industry of Thailand: An empirical forecasting using ARIMA. Brazilian Journal of Operations & Production Management, 18(2), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khusna, H., Mashuri, M., Ahsan, M., Wibawati, W., Aksioma, D. F., & Suhermi, N. (2024). Forecasting number of international tourist arrivals using multi input intervention arima model. BAREKENG: Jurnal Ilmu Matematika dan Terapan, 18(3), 1539–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourentzes, N., Saayman, A., Jean-Pierre, P., Provenzano, D., Sahli, M., Seetaram, N., & Volo, S. (2021). Visitor arrivals forecasts amid COVID-19: A perspective from the Africa team. Annals of Tourism Research, 88, 103197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A., Vici, L., Ramos, V., Giannoni, S., & Blake, A. (2021). Visitor arrivals forecasts amid COVID-19: A perspective from the Europe team. Annals of Tourism Research, 88, 103182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X., Abhari, K., & Wang, W. (2024). Resurgence in paradise: Decoding the patterns of arrivals with different trip purposes in Hawaii’s post-pandemic tourism recovery. Current Issues in Tourism, 27(22), 3636–3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljubotina, P., & Raspor, A. (2022). Recovery of slovenian tourism after COVID-19 and Ukraine crisis. ECONOMICS-Innovative and Economics Research Journal, 10(1), 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-de-Lacalle, J. (2019). Tsoutliers: Detection of outliers in time series (R Package Version 0.6-10). Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/tsoutliers/index.html (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Ma, S., Li, H., Hu, M., Yang, H., & Gan, R. (2023). Tourism demand forecasting based on user-generated images on OTA platforms. Current Issues in Tourism, 27(11), 1814–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makoni, T., Mazuruse, G., & Nyagadza, B. (2023). International tourist arrivals modelling and forecasting: A case of Zimbabwe. Sustainable Technology and Entrepreneurship, 2(1), 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masena, T. E., Mahlangu, S. L., & Shongwe, S. C. (2024a). Time series perspective on the sustainability of the south african food and beverage sector. Sustainability, 16(22), 9746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masena, T. E., Shongwe, S. C., & Yeganeh, A. (2024b). Quantifying loss to the economy using interrupted time series models: An application to the wholesale and retail sales industries in South Africa. Economies, 12(9), 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendieta-Aragón, A., Navío-Marco, J., & Garín-Muñoz, T. (2024). Twitter’s capacity to forecast tourism demand: The case of way of Saint James. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 33(2), 0295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J. C., Lim, C., & Kung, H. H. (2011). Intervention analysis of SARS on Japanese tourism demand for Taiwan. Quality & Quantity, 45, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D. C., Jennings, C. L., & Kulahci, M. (2015). Introduction to time series analysis and forecasting. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, J. J. M., Pol, A. P., Abad, A. S., & Blasco, B. C. (2013). Using the R-MAPE index as a robust measure of forecast accuracy. Psychothema, 25, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naudé, W. A., & Saayman, A. (2005). Determinants of tourist arrivals in Africa: A panel data regression analysis. Tourism Economics, 11(3), 365–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, G. A., Nunes, C. S., & Fernandes, P. O. (2022). Seasonal autoregressive integrated moving average time series model for tourism demand: The case of Sal Island, Cape Verde. In Advances in tourism, technology and systems: Selected papers from ICOTTS (Vol. 2, pp. 11–21). Springer Nature Singapore. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E., Park, J., & Hu, M. (2021). Tourism demand forecasting with online news data mining. Annals of Tourism Research, 90, 103273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, T., Li, W., & Dhakal, T. (2024). Forecasting tourist arrivals in Nepal: A comparative analysis of seasonal models and implications. Journal of Statistical Theory and Applications, 23(3), 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proietti, T., & Lütkepohl, H. (2013). Does the Box–Cox transformation help in forecasting macroeconomic time series? International Journal of Forecasting, 29(1), 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R. T., Wu, D. C., Dropsy, V., Petit, S., Pratt, S., & Ohe, Y. (2021). Visitor arrivals forecasts amid COVID-19: A perspective from the Asia and Pacific team. Annals of Tourism Research, 88, 103155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, W., & Sumargo, B. (2023). Forecasting the number of foreign tourist using intervention and ARCH analysis. In AIP conference proceedings (Vol. 2588, p. 050014). AIP Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2025). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.rproject.org/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Rianda, F., & Usman, H. (2023). Forecasting tourism demand during the COVID-19 pandemic: ARIMAX and intervention modelling approaches. BAREKENG: Jurnal Ilmu Matematika dan Terapan, 17(1), 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogan, M., & Skinner, C. (2020). The COVID-19 crisis and the South African informal economy: ‘Locked-out’ of livelihoods and employment, cape town: University of cape town, national income dynamics study (NIDS)—Coronavirus rapid mobile survey, report 10. Available online: https://www.datafirst.uct.ac.za/dataportal/index.php/citations/6835 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Su, J. J., Amsler, C., & Schmidt, P. (2012). A note on the size of the KPSS unit root test. Economics Letters, 117(3), 697–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhayaya, R. P. (2021). Forecasting international tourists arrival to Nepal using autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA). Janapriya Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 10(01), 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venables, W., & Ripley, B. (2002). Modern applied statistics with S (4th ed.). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viljoen, A., Saayman, A., & Saayman, M. (2019). Determinants influencing inbound arrivals to Africa. Tourism Economics, 25(6), 856–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramasinghe, K., & Ratnasiri, S. (2020). The role of disaggregated search data in improving tourism forecasts: Evidence from Sri Lanka. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(19), 2740–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D. C. W., Ji, L., He, K., & Tso, K. F. G. (2020). Forecasting tourist daily arrivals with a hybrid Sarima–LSTM approach. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 45(1), 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R., Liu, K., Su, C., Takeda, S., Zhang, J., & Liu, S. (2023). Quantitative analysis of seasonality and the impact of COVID-19 on tourists’ use of urban green space in okinawa: An ARIMA modeling approach using web review data. Land, 12(5), 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeileis, A., & Hothorn, T. (2002). Diagnostic checking in regression relationships. R News, 2(3), 7–10. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/doc/Rnews/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Zenker, S., & Kock, F. (2020). The coronavirus pandemic—A critical discussion of a tourism research agenda. Tourism Management, 81, 104164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | AIC | BIC | RMSE | MAPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARIMA | 2756.59 | 2764.98 | 19,319.17 | 6.37% |

| SARIMA | 2758.85 | 2772.83 | 19,154.32 | 6.41% |

| SARIMA | 2760.82 | 2777.59 | 19,158.69 | 6.42% |

| SARIMA | 2761.69 | 2781.26 | 19,188.49 | 6.48% |

| SARIMA | 2763.52 | 2785.89 | 19,238.54 | 6.30% |

| SARIMA | 2786.02 | 2791.61 | 21,842.57 | 6.97% |

| SARIMA | 2760.83 | 2777.60 | 19,157.33 | 6.42% |

| SARIMA | 2760.64 | 2777.42 | 19,133.12 | 6.42% |

| SARIMA | 2762.13 | 2778.90 | 19,296.84 | 6.45% |

| SARIMA | 2758.80 | 2772.78 | 19,163.99 | 6.31% |

| Parameters | Estimate | Standard Error | z Value | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.618673 | 0.079557 | −7.7765 | 7.458 × 10−15 | |

| −0.631800 | 0.075798 | −8.3353 | 2.2 × 10−16 |

| Parameters | Estimate | Standard Error | z Value | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −4.0098 × 10−1 | 8.2597 × 10−2 | −4.8546 | 1.206 × 10−6 | |

| −6.0552 × 10−1 | 9.0910 × 10−2 | −6.6607 | 2.726 × 10−11 | |

| AO16 | −3.4850 × 104 | 9.1565 × 103 | −3.8060 | 1.412 × 10−6 |

| AO18 | 1.4094 × 105 | 9.4044 × 103 | 14.9864 | 2.2 × 10−16 |

| Parameters | Estimate | Standard Error | z Value | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.157208 | 0.144642 | 1.0869 | 0.2771 | |

| −0.707052 | 0.102821 | −6.8765 | 6.133 × 10−12 | |

| −0.689539 | 0.095678 | −7.2069 | 5.725 × 10−13 | |

| 0.097781 | 0.128587 | 0.7604 | 0.4470 |

| Parameters | Estimate | Standard Error | z Value | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −8.2420 × 10−1 | 1.0910 × 10−1 | −7.5547 | 4.200 × 10−14 | |

| 6.3776 × 10−1 | 1.4476 × 10−1 | 4.4057 | 1.054 × 10−5 | |

| −4.4023 × 10−1 | 1.1193 × 10−1 | −3.9331 | 8.386 × 10−5 | |

| −1.7230 × 10−1 | 1.2424 × 10−1 | −1.3868 | 0.1654992 | |

| AO16 | −4.0093 × 104 | 6.2484 × 103 | −6.4166 | 1.394 × 10−10 |

| AO18 | 1.3570 × 105 | 6.3495 × 103 | 21.3725 | 2.2 × 10−16 |

| AO49 | −2.7574 × 104 | 6.4845 × 103 | −4.2522 | 2.117 × 10−5 |

| AO76 | −2.8544 × 104 | 6.2195 × 103 | −4.5894 | 4.445 × 10−6 |

| IO52 | −1.9628 × 104 | 6.0211 × 103 | −3.2599 | 0.0011146 |

| IO56 | 1.4032 × 104 | 6.0853 × 103 | 2.3058 | 0.0211197 |

| IO61 | −2.2002 × 104 | 6.3994 × 103 | −3.4382 | 0.0005857 |

| IO112 | −2.8725 × 104 | 6.3458 × 103 | −4.5266 | 5.995 × 10−6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mphanya, A.M.; Shongwe, S.C.; Masena, T.E.; Koning, F.F. Statistical Quantification of the COVID-19 Pandemic’s Continuing Lingering Effect on Economic Losses in the Tourism Sector. Economies 2025, 13, 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13120362

Mphanya AM, Shongwe SC, Masena TE, Koning FF. Statistical Quantification of the COVID-19 Pandemic’s Continuing Lingering Effect on Economic Losses in the Tourism Sector. Economies. 2025; 13(12):362. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13120362

Chicago/Turabian StyleMphanya, Amos Mohau, Sandile Charles Shongwe, Thabiso Ernest Masena, and Frans Frederick Koning. 2025. "Statistical Quantification of the COVID-19 Pandemic’s Continuing Lingering Effect on Economic Losses in the Tourism Sector" Economies 13, no. 12: 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13120362

APA StyleMphanya, A. M., Shongwe, S. C., Masena, T. E., & Koning, F. F. (2025). Statistical Quantification of the COVID-19 Pandemic’s Continuing Lingering Effect on Economic Losses in the Tourism Sector. Economies, 13(12), 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13120362