The Environmental Kuznets Curve and CO2 Emissions Under Policy Uncertainty in G7 Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

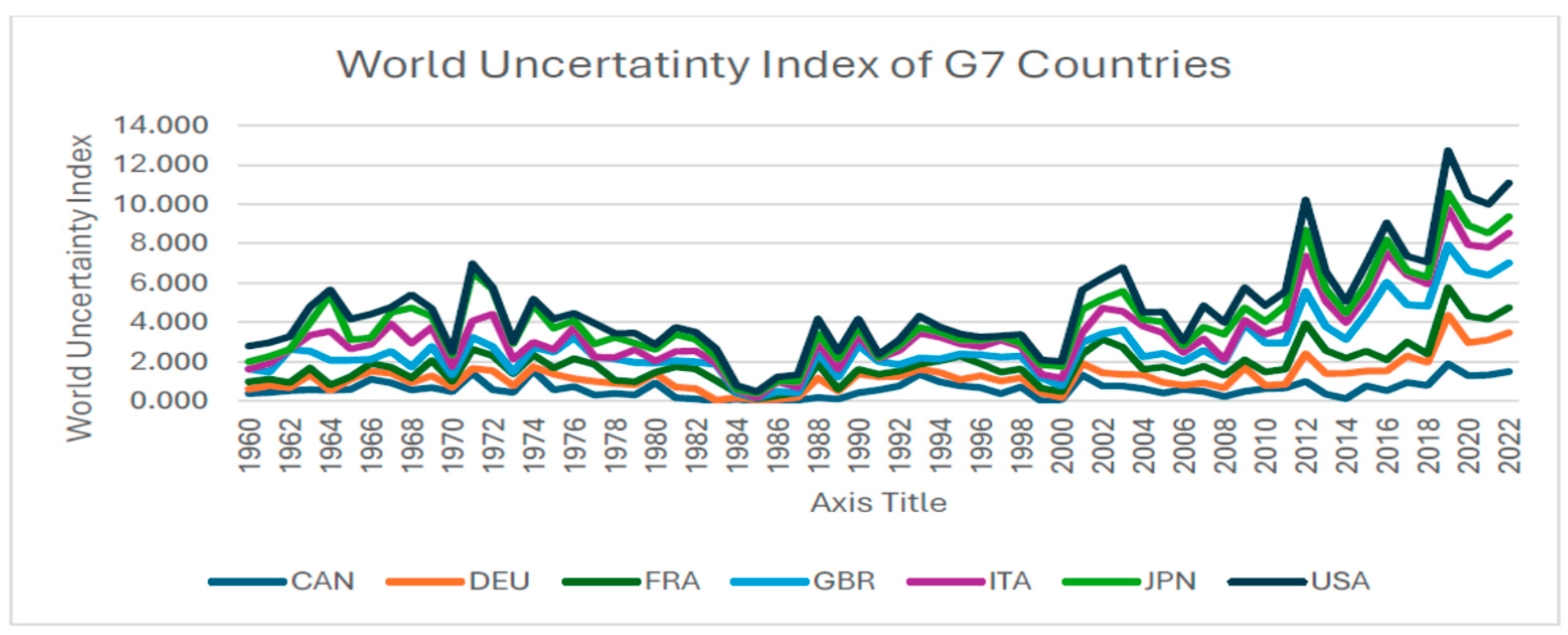

2. World Uncertainty Index

3. Methodology

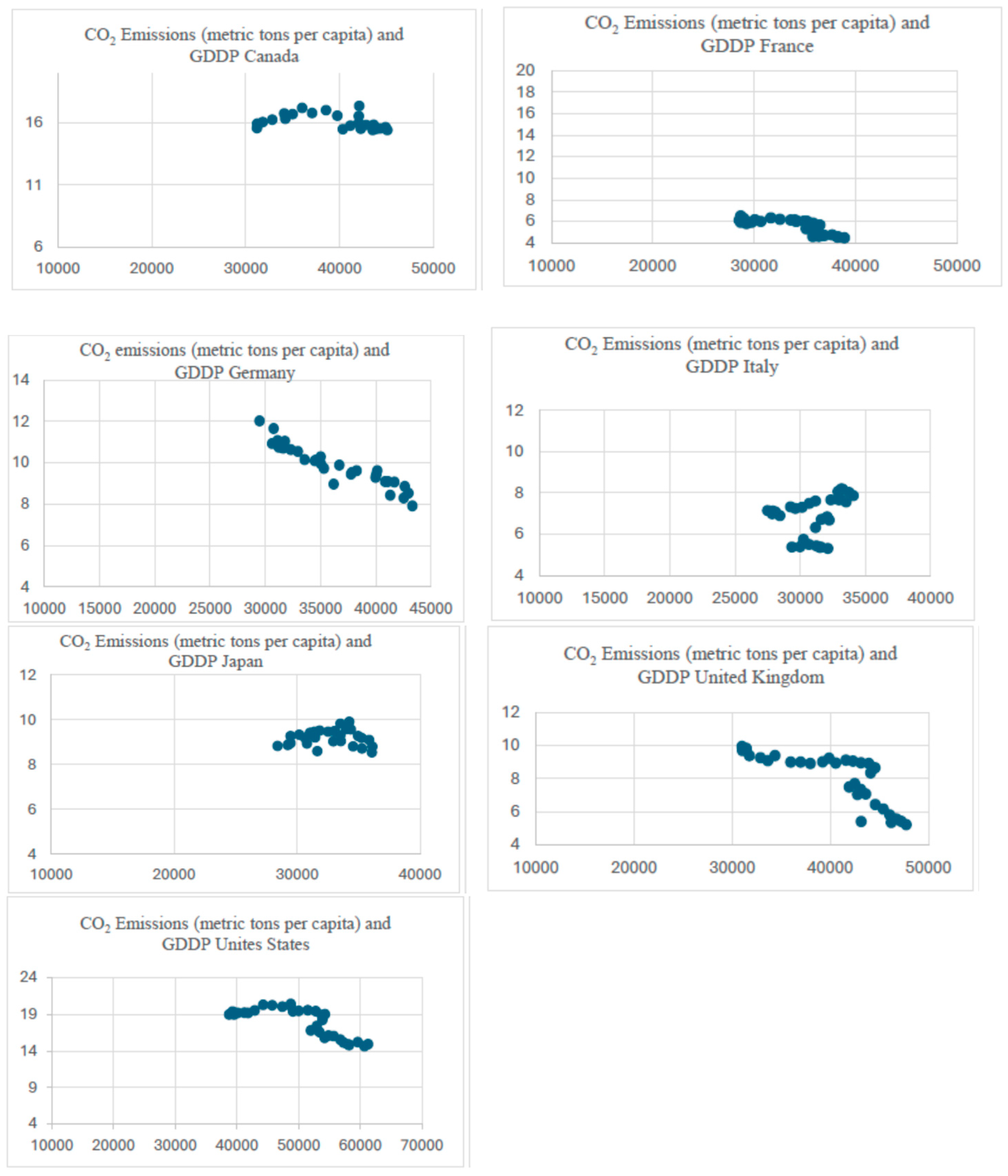

4. Data and Descriptive Statistics

5. Empirical Approach and Results

6. Income Turning Point

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 13 August 2024). |

| 2 | https://www.policyuncertainty.com/wui_quarterly.html (accessed on 13 August 2024). Note: Data used in this study are available in the links provided. |

References

- Adedoyin, F., & Zakari, A. (2020). Energy consumption, economic expansion, and CO2 emission in the UK: The role of economic policy uncertainty. Science of the Total Environment, 738, 140014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahir, H., Bloom, N., & Furceri, D. (2022). The world uncertainty index (NBER Working Papers 29763). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Aldy, J. E. (2005). An environmental Kuznets curve analysis of U.S. state-level carbon dioxide emissions. The Journal of Environment & Development, 14(1), 48–72. [Google Scholar]

- Allard, A., Takman, J., Uddin, G. S., & Ahmed, A. (2018). The N-shaped environmental Kuznets curve: An empirical evaluation using a panel quantile regression approach. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 25, 5848–5861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mulali, U., Solarin, S. A., & Ozturk, I. (2016). Investigating the presence of the environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) hypothesis in Kenya: An autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) approach. Natural Hazards, 80, 1729–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, A., & Dogan, E. (2021). The role of economic policy uncertainty in the energy-environment nexus for China: Evidence from the novel dynamic simulations method. Journal of Environmental Science and Management, 292, 112865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anser, M. K., Apergis, N., & Syed, Q. R. (2021). Impact of economic policy uncertainty on CO2 emissions: Evidence from top ten carbon emitter countries. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28(23), 29369–29378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apergis, N., & Ozturk, I. (2015). Testing environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis in Asian countries. Ecological Indicators, 52, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armeanu, D., Vintilă, G., Andrei, J., Gherghina, Ş., Drăgoi, M., & Teodor, C. (2018). Exploring the link between environmental pollution and economic growth in EU-28 countries: Is there an environmental Kuznets curve? PLoS ONE, 13(5), e0195708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrow, K., Bolin, B., Costanza, R., Dasgupta, P., Folke, C., Holling, C. S., Jansson, B.-O., Levin, S., Mäler, K.-G., Perrings, C., & Pimentel, D. (1995). Economic growth, carrying capacity, and the environment. Science, 268, 520–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, R., Sohag, K., Abdullah, S., & Jaafar, M. (2015). CO2 emissions, energy consumption, economic and population growth in Malaysia. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 41, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, N., Bond, S., & Van Reenen, J. (2007). Uncertainty and investment dynamics. The Review of Economic Studies, 74(2), 391–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, M., Khosravi, H., De Laat, M., Bergdahl, N., Negrea, V., Oxley, E., Pham, P., Chong, S. W., & Siemens, G. (2024). A meta systematic review of artificial intelligence in higher education: A call for increased ethics, collaboration, and rigour. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 21, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L., & Rothstein, H. (2007). Meta-analysis fixed effects vs. random effects. Biostat. [Google Scholar]

- Breitung, J., & Das, S. (2005). Panel unit root tests under cross-sectional dependence. Statistica Neerlandica, 59, 414–433. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, J. W., & Bergstrom, J. C. (2010). U.S. state-level carbon dioxide emissions: A spatial-temporal econometric approach of the environmental Kuznets curve (Faculty Series 96031). University of Georgia, Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics.

- Cavlovic, T., Baker, K., Berrens, R., & Gawande, K. (2000). A meta-analysis of environmental Kuznets curve studies. Agricultural and Resource Economics Review, 29(1), 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejuan-Bitria, D., & Ghirelli, C. (2021). Economic policy uncertainty and investment in Spain. SERIEs, 12, 351–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECB Economic Bulletin. (2020). Issue 6. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/economic-bulletin/html/eb202006.en.html (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Fosten, J., Morley, B., & Taylor, T. (2012). Dynamic misspecification in the environmental Kuznets curve: Evidence from CO2 and SO2 emissions in the United Kingdom. Ecological Economics, 76, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavriilidis, K. (2021). Measuring climate policy uncertainty. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3847388 (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Green, W. H. (2008). Econometric analysis (6th ed.). Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, G. M., & Krueger, A. B. (1991). Environmental impacts of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NBER Working Paper 3914). National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, G. M., & Krueger, A. B. (1995). Economic growth and the environment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(2), 353–377. [Google Scholar]

- Guesmi, K., Makrychoriti, P., & Spyrou, S. (2023). The relationship between climate risk, climate policy uncertainty, and CO2 emissions: Empirical evidence from the U.S. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 212, 610–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M., Chand, S., & Ul Haq, Z. (2023). Economic policy uncertainty and CO2 emissions: A comparative analysis of developed and developing nations. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30, 15034–15043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jebli, M., & Youssef, S. (2015). The environmental Kuznets curve, economic growth, renewable and non-renewable energy, and trade in Tunisia. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 47, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacprzyk, A., & Kuchta, Z. (2020). Shining a new light on the environmental Kuznets curve for CO2 emissions. Energy Economics, 87, 104704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, A. K. (2023). Investigating the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis for CO2 emissions in Nordic countries. International Journal of Environmental Studies, 81(4), 1637–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karavias, Y., & Tzavalis, E. (2014). Testing for unit roots in short panels allowing for a structural break. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis, 76, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S., Ullah, M., Shahzad, M., Khan, U., Khan, U., Eldin, S., & Alotaibi, A. (2022). Spillover connectedness among global uncertainties and sectorial indices of Pakistan: Evidence from quantile connectedness approach. Sustainability, 14(23), 15908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, B., & Mysami, R. (2015). Investigating the effect of forest per capita in explaining the EKC hypothesis for CO2 in the U.S. Journal of Environmental Economics and Policy, 4(3), 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, B. S., Li, H., & Berrens, R. P. (2011). Further investigation of environmental Kuznets curve studies using meta-analysis. International Journal of Economics and Statistics, 22(S11), 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kolev, A., & Randall, T. (2024). The effect of uncertainty on investment: Evidence from EU survey data (EIB Working Paper 2024/02). European Investment Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C. C., Chiu, Y. B., & Sun, C. H. (2009). Does one size fit all? A reexamination of the environmental Kuznets curve using the dynamic panel data approach. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 31(4), 751–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, A., Lin, F., & Chu, J. (2002). Unit root tests in panel data: Asymptotic and finite-sample properties. Journal of Econometrics, 108, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P., Narayan, S., Ren, Y., Jiang, Y., Baltas, K., & Sharp, B. (2022). Re-examining the income–CO2 emissions nexus using the new kink regression model: Does the Kuznets curve exist in G7 countries? Sustainability, 14, 3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W. (2020). EKC test study on the relationship between carbon dioxide emission and regional economic growth. Carbon Management, 11(4), 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Zhang, S., & Bae, J. (2017). The impact of renewable energy and agriculture on carbon dioxide emissions: Investigating the environmental Kuznets curve in four selected Asian countries. Journal of Cleaner Production, 164, 239–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzner, A., Meyer, B., & Oberhofer, H. (2023). Trade in times of uncertainty. The World Economy, 46(9), 2564–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutinho, V., Varum, C., & Madaleno, M. (2017). How economic growth affects emissions? An investigation of the environmental Kuznets curve in Portuguese and Spanish economic activity sectors. Energy Policy, 106, 326–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, M., Hameed, G., Ahmed, S., Fahlevi, M., Aljuaid, M., & Saniuk, S. (2024). How does economic policy uncertainty impact CO2 emissions? Investigating investment’s role across 22 economies (1997–2021). Energy Reports, 11, 5083–5091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, M. A., Huynh, T. L. D., & Tram, H. T. X. (2019). Role of financial development, economic growth & foreign direct investment in driving climate change: A case of emerging ASEAN. Journal of Environmental Management, 242, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pata, U. (2018). Renewable energy consumption, urbanization, financial development, income and CO2 emissions in Turkey: Testing EKC hypothesis with structural breaks. Journal of Cleaner Production, 187, 770–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N., Pham, T., Cao, V., Tran, H., & Vo, X. (2020). The impact of international trade on environmental quality: Implications for law. Asian Journal of Law and Economics, 11(1), 20200001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirgaip, B., Bayrakdar, S., & Kaya, M. (2023). The role of government spending within the environmental Kuznets curve framework: Evidence from G7 countries. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30, 81513–81530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbi, F., Akbar, D., & Kabir, S. (2015). Environmental Kuznets curve for carbon emissions: A cointegration analysis for Bangladesh. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy, 5(1), 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, T., & Fumagalli, E. (2018). Greening the power generation sector: Understanding the role of uncertainty. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 91, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqib, M., & Benhmad, F. (2021). Updated meta-analysis of environmental Kuznets curve: Where do we stand? Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 86, 106503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sephton, P., & Mann, J. (2016). Compelling evidence of an environmental Kuznets curve in the United Kingdom. Environmental and Resource Economics, 64(2), 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafik, N., & Bandyopadhyay, S. (1992). Economic growth and environmental quality: Time series and cross-country evidence (Policy Research Working Paper Series 904). The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y., Zhang, M., & Zhou, M. (2019). Study on the decoupling relationship between CO2 emissions and economic development based on two-dimensional decoupling theory: A case between China and the United States. Ecological Indicators, 102, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, D. (2004). The rise and fall of the environmental Kuznets curve. World Development, 32(8), 1419–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, T., Hossain, M. S., Voumik, L. C., & Raihan, A. (2023). Does globalization escalate the carbon emissions? Empirical evidence from selected next-11 countries. Energy Reports, (10), 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulucak, D. R., & Khan, S. (2020). Determinants of the ecological footprint: Role of renewable energy, natural resources, and urbanization. Sustainable Cities and Society, 54, 101996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., & Xiao, K. (2020). Does economic policy uncertainty affect CO2 emissions? Empirical Evidence from the United States. Sustainability, 12(21), 9108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Description | Mean | St. Deviation | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lnPPCO2 | Natural log of per capita carbon emissions (dependent variable) | 2.425 | 0.404 | 1.162 | 3.146 |

| lnGDPP | Natural log of GDP per capita measured (US dollars in 2015 prices) | 10.192 | 0.397 | 8.761 | 10.923 |

| (lnGDPP)2 | Square of natural log of GDP per capita (US dollar in 2015 prices) | 104.025 | 8.001 | 76.763 | 119.321 |

| lnWUI | Natural log of World Uncertainty Index | 0.461 | 0.278 | 0.000 | 1.744 |

| Variables | FE Model | RE Model |

|---|---|---|

| Coefficients | Coefficients | |

| lnGDPP | 11.735 *** | 11.697 *** |

| (0.704) | (0.711) | |

| (lnGDPP)2 | −0.555 *** | −0.535 *** |

| (0.035) | (0.035) | |

| lnWUI | −0.059 ** | −0.060 ** |

| (0.026) | (0.026) | |

| INTERCEPT | −57.074 *** | −56.889 *** |

| (3.536) | (3.571) | |

| σu | 0.387 | 0.249 |

| σe | 0.141 | 0.141 |

| ρ (fraction of variance due to u_i) | 0.881 | 0.755 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koirala, B.; Pradhan, G.; Mensah, E.C. The Environmental Kuznets Curve and CO2 Emissions Under Policy Uncertainty in G7 Countries. Economies 2025, 13, 363. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13120363

Koirala B, Pradhan G, Mensah EC. The Environmental Kuznets Curve and CO2 Emissions Under Policy Uncertainty in G7 Countries. Economies. 2025; 13(12):363. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13120363

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoirala, Bishwa, Gyan Pradhan, and Edwin Clifford Mensah. 2025. "The Environmental Kuznets Curve and CO2 Emissions Under Policy Uncertainty in G7 Countries" Economies 13, no. 12: 363. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13120363

APA StyleKoirala, B., Pradhan, G., & Mensah, E. C. (2025). The Environmental Kuznets Curve and CO2 Emissions Under Policy Uncertainty in G7 Countries. Economies, 13(12), 363. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13120363