Integrating Indigenous Financial Frameworks in Zimbabwean Banks: A Decolonial Economics’ Approach to Sustainable Finance

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Analytical and Theoretical Framework

1.2. Five Stages Theory of Sustainability

- Stage 1: Very Weak (Compliance Sustainability)

- Stage 2: Weak (Business-Centered Sustainability)

- Stage 3: Intermediate (Systemic or Mixed Sustainability)

- Stage 4: Strong (Regenerative Sustainability)

- Stage 5: Very Strong (Co-evolutionary Sustainability)

1.3. Decolonial Economics and the Pluriverse

1.4. Marxist Immanent Critique of Sustainable Finance

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Worldview Orientation and Epistemic Dominance Across Banks

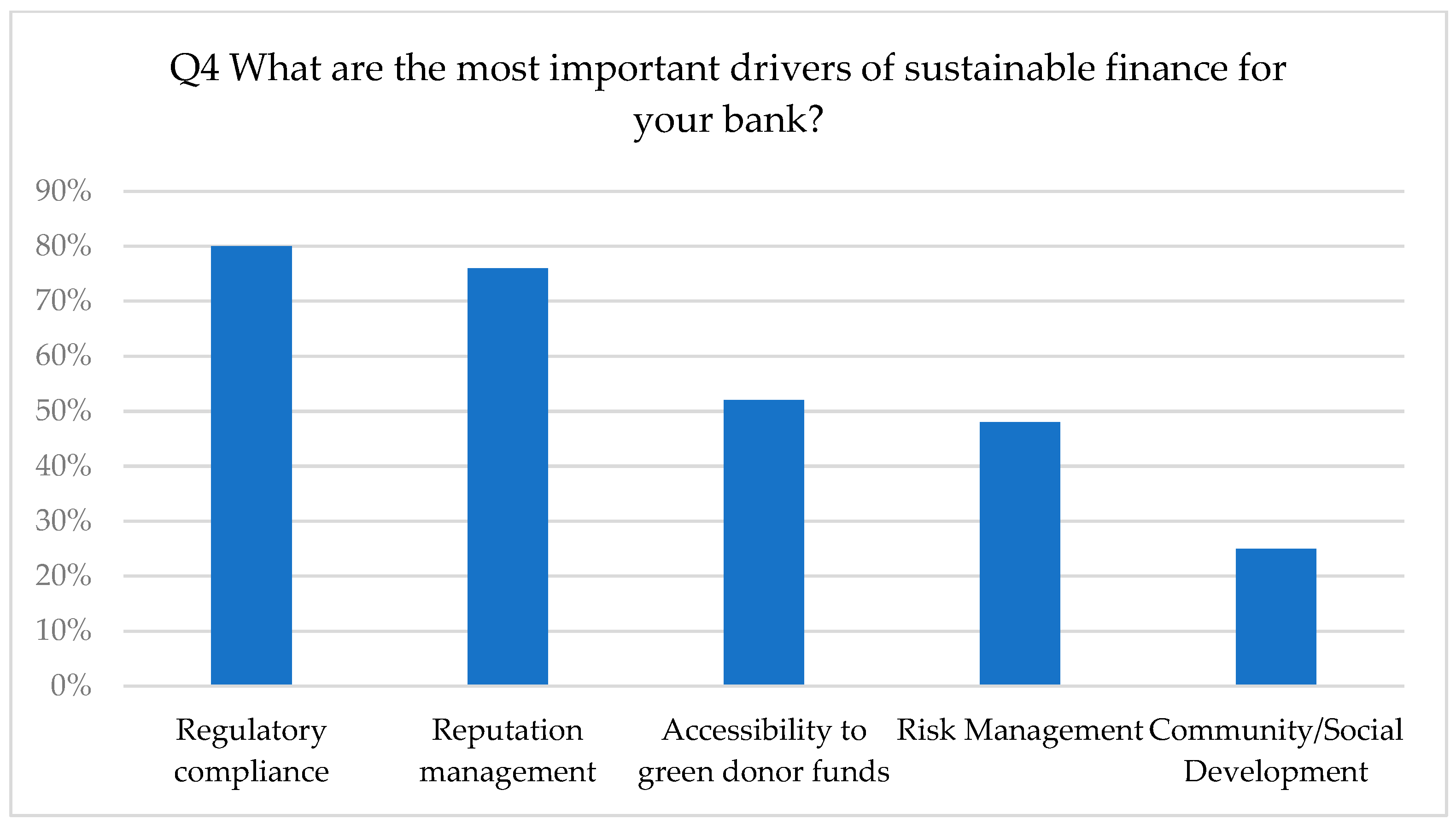

3.2. High Perception of Euro-American Centric Global Sustainability Policy Frameworks

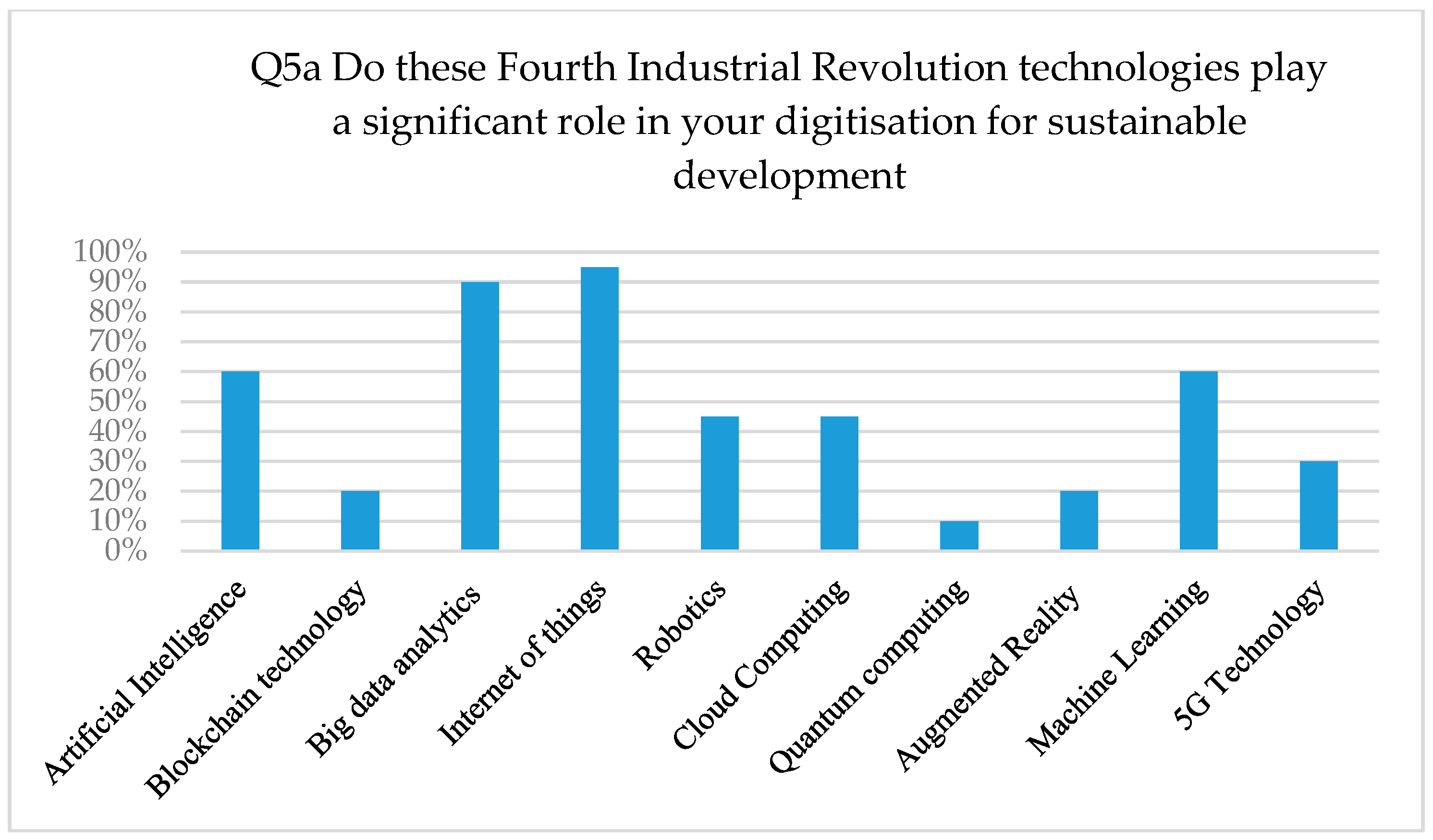

3.3. High Adoption of Euro-American Centric Technology

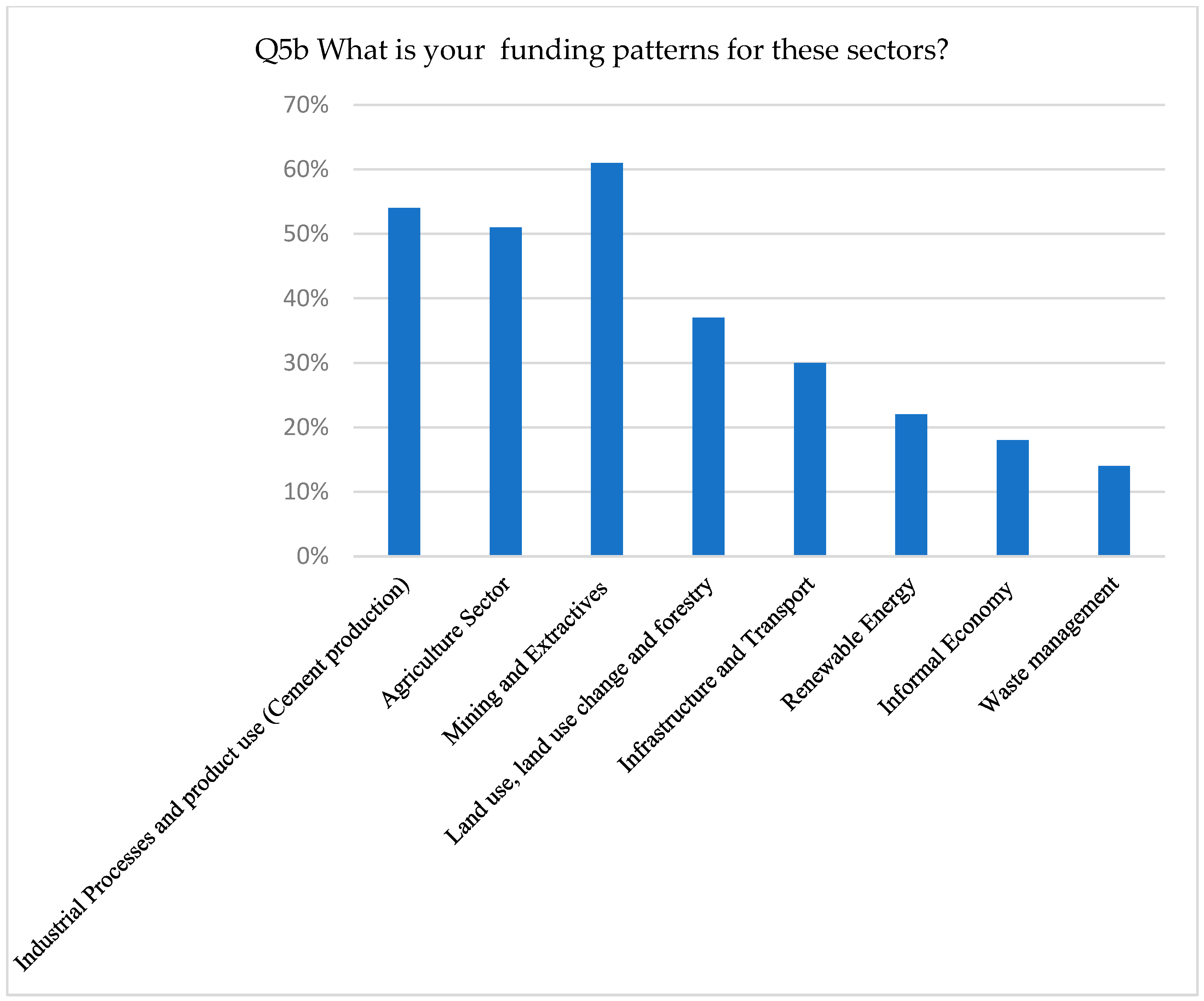

3.4. Patterns of Sectoral Investments Rationalization

3.5. Absence of Indigenous and Pluriverse Epistemologies

4. Discussion

4.1. Euro-American Centric Models Perpetuate Weak Sustainability Theory

4.2. Sustainability Colonialism

4.3. Epistemic Exclusion and Violence

4.4. Recommendations and Implications: Decolonial Alternatives

4.4.1. Reject Radically Euro-American Centric Models in Favor of Indigenous African Frameworks

4.4.2. Hybrid Approach: Integrate Afrocentric Sustainable Finance Views into Euro-American Centric Models

4.4.3. Reform Education and Training in Economics, Banking & Finance

4.4.4. Include Indigenous Values in Sustainability Standards

4.4.5. Reduce External Dependence and Financial Subordination

4.4.6. Increase Africans’ Representation in Standard Setting Bodies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, S. K. (2024). How to choose a sampling technique and determine sample size for research: A simplified guide for researchers. Oral Oncology Reports, 12, 100662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajitoni, B. D. (2024). Ubuntu and the philosophy of community in African thought: An exploration of collective identity and social harmony. Journal of African Studies and Sustainable Development, 7(3), 1–15. Available online: https://acjol.org/index.php/jassd/article/view/5672/5496 (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Amin, S. (1972). Underdevelopment and dependence in black Africa: Historical origin. Journal of Peace Research, 9(2), 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Valencia, J. A. (2025). What does decolonizing research look like? Lessons from an intercultural participatory study with Indigenous university students in Colombia. Language and Intercultural Communication, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benyera, E. (2021). The fourth industrial revolution and the recolonisation of Africa. Taylor and Francis. Available online: https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/48368 (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Bispo Júnior, J. P. (2022). Social desirability bias in qualitative health research. Revista de Saude Publica, 56, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, P. (2023). ‘Nothing has changed, South Africa’s sub-imperialist role has been reinforced’: Samir Amin’s durable critique of apartheid/post-apartheid political economy. Politikon, 50(4), 314–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruna, N. (2022). Green extractivism and financialisation in Mozambique: The case of Gilé National Reserve. Review of African Political Economy, 49(171), 138–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilisa, B., Major, T. E., & Khudu-Petersen, K. (2017). Community engagement with a postcolonial, African-based relational paradigm. Qualitative Research, 17(3), 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilisa, B., & Mertens, D. M. (2021). Indigenous made in Africa evaluation frameworks: Addressing epistemic violence and contributing to social transformation. American Journal of Evaluation, 42(2), 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coen, D., Herman, K., & Pegram, T. (2022). Are corporate climate efforts genuine? An empirical analysis of the climate ‘talk–walk’ hypothesis. Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(7), 3040–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Crowther, D., & Seifi, S. (2022). Introduction: Managing the pillars of sustainable development. Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, J. O. (2024). Decolonizing climate change response: African indigenous knowledge and sustainable development. Frontiers in Sociology, 9, 1456871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demastus, J., & Landrum, N. E. (2024). Organizational sustainability schemes align with weak sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment, 33(2), 707–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, A. (2021). Spreading ‘green’ infrastructural harm: Mapping conflicts and socio-ecological disruptions within the European Union’s transnational energy grid. Globalizations, 20(6), 907–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golka, P. (2024). Epistemic gerrymandering: ESG, impact investing, and the financial governance of sustainability. Review of International Political Economy, 31(6), 1894–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gram-Hanssen, I., Schafenacker, N., & Bentz, J. (2022). Decolonizing transformations through ‘right relations’. Sustainability Science, 17, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumede, V. (2023). Post-colonial development in Africa—Samir Amin’s lens. Politikon, 50(4), 438–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haag, S. (2023). Old colonial power in new green financing instruments. Approaching financial subordination from the perspective of racial capitalism in renewable energy finance in Senegal. Geoforum, 145, 103641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. (2012). The ‘new’ imperialism: Accumulation by dispossession. Karl Marx. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. (2016). A commentary on a theory of imperialism. In A theory of imperialism (pp. 154–172). Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Held, M. B. E. (2019). Decolonizing research paradigms in the context of settler colonialism: An unsettling, mutual, and collaborative effort. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18(2), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickel, J., Dorninger, C., Wieland, H., & Suwandi, I. (2022). Imperialist appropriation in the world economy: Drain from the global South through unequal exchange, 1990–2015. Global Environmental Change, 73, 102467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J. L., Ghorpade, S., Galappaththi, M., & Lesbarrères, D. (2023). Toward decolonizing sustainability research: A systematic process to guide critical reflections. Facets, 8(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J., & Larsen, M. (2025). Green financial planning: A state-capital relationship meta-governed through the Paris agreement. New Political Economy, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamuti, T. (2022). Integration of indigenous knowledge systems in Zimbabwe’s climate change policy. In E. E. Ebhuoma, & L. Leonard (Eds.), Indigenous knowledge and climate governance. Sustainable Development Goals Series. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, A., Salleh, A., Escobar, A., Demaria, F., & Acosta, A. (2019). Pluriverse: A post-development dictionary. Tulika Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kvangraven, I. H., & Kesar, S. (2022). Standing in the way of rigor? Economics meeting with the decolonization agenda. Review of International Political Economy, 30(5), 1723–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwet, M. (2019). Digital colonialism: US empire and the new imperialism in the Global South. Race and Class, 60(4), 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langman, L. (2017). Critical theory. In The Wiley-Blackwell encyclopedia of social theory. Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W., Eustachio, J. H. P. P., Fedoruk, M., & Lisovska, T. (2024). War in Ukraine: An overview of environmental impacts and consequences for human health. Frontiers in Sustainable Resource Management, 3, 1423444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malapane, O. L., Chanza, N., & Musakwa, W. (2024). Transmission of indigenous knowledge systems under changing landscapes within the Vhavenda community, South Africa. Environmental Science & Policy, 161, 103861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano, A. (2022). Conducting focus groups in realist evaluation. Evaluation (London, England: 1995), 28(4), 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastini, R., Kallis, G., & Hickel, J. (2021). A new green deal without growth? Ecological Economics, 179, 106832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matanzima, J. (2024). “Disempowered by the transition”: Manipulated and coerced agency in displacements induced by accelerated extraction of energy transition minerals in Zimbabwe. Energy Research & Social Science, 11, 103727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, L. (2025). The challenges of decolonising sustainability and the environment in Development Studies (DS). European Journal of Development Research, 37, 454–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, D. M. (2010). Transformative mixed methods research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(6), 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, D. M., & Chilisa, B. (2024). Transformative and indigenous frameworks in international development. International Journal for Transformative Research, 11(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorelli, M. (2021). What do we mean by sustainable finance? Assessing existing frameworks and policy risks. Sustainability, 13, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignolo, W. D., & Walsh, C. E. (2018). On decoloniality: Concepts, analytics, praxis. Duke University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosa, I. A. (2023). Financialisation: Measurement, driving forces and consequences. Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D. L., & Krueger, R. A. (1993). When to use focus groups and why. In D. L. Morgan (Ed.), Successful focus groups: Advancing the state of the art (pp. 3–19). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabudere, D. W. (2006). Towards an Afrokology of knowledge production and African regeneration. International Journal of African Renaissance Studies—Multi-, Inter- and Transdisciplinarity, 1(1), 7–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. (2020). Decolonization, development and knowledge in Africa: Turning over a new leaf. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nibbeling, N., Simons, M., Sporrel, K., & Deutekom, M. (2021). A focus group study among inactive adults regarding the perceptions of a theory-based physical activity app. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 528388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niehoff, S. (2022). Aligning digitalisation and sustainable development? Evidence from the analysis of worldviews in sustainability reports. Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(5), 2546–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normann, S. (2021). Green colonialism in the Nordic context: Exploring Southern Saami representations of wind energy development. Journal of Community Psychology, 49, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamnjoh, F. B. (2019). Decolonizing the university in Africa. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamnjoh, F. B. (2024). Incompleteness as a framework for convivial scholarship and practice in healing. Acta Academica: Critical Views on Society, Culture and Politics, 56(1), 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuji, A. A. (2024). Evolution of sustainable finance and the ontological imperatives for an Afrocentric model. Afreximbank contemporary issues in African trade and trade finance. Available online: https://www.mfw4a.org/sites/default/files/resources/ciat_2024-2.pdf#page=66 (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Poyser, A., & Daugaard, D. (2023). Indigenous sustainable finance as a research field: A systematic literature review on indigenising ESG, sustainability and indigenous community practices. Accounting and Finance, 63(1), 47–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quijano, A. (2000). Coloniality of power and eurocentrism in Latin America. Nepantla: Views from South, 15(2), 533–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raworth, K. (2017). Why it’s time for doughnut economics. Progressive Review, 24(3), 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, B. S. (2014). Epistemologies of the south: Justice against Epistemicide. Paradigm Publishers. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2019). Research methods for business students (8th ed.). New York Pearson Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Sayson, C. M., Suppiah, S., Denardin, A., Oliveira, L., Maldonado-Torres, N., & Mhlahlo, A. (2024). Colonial sustainability: Tracing the sustainability industry’s ecocidal lineage from the doctrine of discovery. Interdisciplinary Journal of Partnership Studies, 11(1), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, K., & Vanham, P. (2021). Stakeholder capitalism: A global economy that works for progress, people and planet. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, T. (2022). Immanent critique and particular moral experience. Critical Horizons, 23(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugar, T. E. (2023). The fourth industrial revolution, techno-colonialism, and the Sub-Saharan Africa response. Filosofia Theoretica: Journal of African Philosophy, Culture and Religions, 12(1), 33–48. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-filosofia_v12_n1_a3 (accessed on 1 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- van Norren, D. E. (2022). African ubuntu and sustainable development goals: Seeking human mutual relations and service in development. Third World Quarterly, 43(12), 2791–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Herrejón, P., Bauwens, T., & Calisto, F. M. (2022). Challenging dominant sustainability worldviews on the energy transition: Lessons from Indigenous communities in Mexico and a plea for pluriversal technologies. World Development, 150, 105725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willard, B. (2012). The new sustainability advantage: Seven business case benefits of a triple bottom (10th Anniversary ed.). New Society Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, R. K., & Brown, D. (2024). Epistemic justice and critical minerals–Towards a planetary just transition. The Extractive Industry and Society, 18, 101463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziai, A. (2019). Towards a more critical theory of ‘development’ in the 21st century. Development and Change, 50(2), 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziai, A. (2024). Beyond the sustainable development goals: Post-development Alternatives. In H. Melber, U. Kothari, L. Camfield, & K. Biekart (Eds.), Challenging global development. EADI Global Development Series. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zylinski, S. (2024). Coloniality dressed in green: In its current form, climate finance risks becoming a new tool for colonial rule. Global Political Economy, 3(2), 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phase | Data Type | Method | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Quantitative | Structured Questionnaires (n = 289) | To objectively measure the prevalence and distribution of worldviews. |

| 2 | Qualitative | Focus Groups (n = 30) | To contextualize and validate identified sustainability worldviews |

| Archival analysis | Documents (n = 45) | To analyze how worldviews are embedded in institutional texts |

| Feature | Ubuntu ESG Models | Euro-American ESG Models |

|---|---|---|

| Philosophy | Communalism: I am because we are | Neoliberalism and shareholder capitalism |

| Epistemology | Communal and relational | Individualist and investor-focused |

| Ontology | Pluriverse: multiple truths and realities coexist | Universalist: one size fit truth |

| Core Values | People & community first, solidarity compassion, dignity, interconnectedness | Profitability, capital accumulation, stakeholder engagement |

| Environmental Focus | Ecocentric: nature is symbiotic, intergenerational and land centered. | Anthropocentric: nature is a resource to be managed for long term value. Risk based emission reduction. |

| Social Ethos | Community first, cultural respect, and human dignity—“We” | Diversity, equity, inclusion and safety based on individualistic human rights—“I” |

| Governance | Ethical and participatory leadership based on moral duty and communal accountability | Board governance driven by audits, fiduciary duty and shareholder capitalism |

| Decision Making | Consensus driven—inclusive of all community voices | Board led, shareholder informed & guided by business judgment. |

| View of Individual | Community well-being drives individual’s well-being | Individual rights and interests are balanced with stakeholder needs |

| Reporting Approach | Narrative, spiritual and community based | Positivist and quantitative: investor material, data centric and standardized disclosures. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tepetepe, G.; Obokoh, L.O. Integrating Indigenous Financial Frameworks in Zimbabwean Banks: A Decolonial Economics’ Approach to Sustainable Finance. Economies 2025, 13, 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13120343

Tepetepe G, Obokoh LO. Integrating Indigenous Financial Frameworks in Zimbabwean Banks: A Decolonial Economics’ Approach to Sustainable Finance. Economies. 2025; 13(12):343. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13120343

Chicago/Turabian StyleTepetepe, Gilbert, and Lawrence Ogechukwu Obokoh. 2025. "Integrating Indigenous Financial Frameworks in Zimbabwean Banks: A Decolonial Economics’ Approach to Sustainable Finance" Economies 13, no. 12: 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13120343

APA StyleTepetepe, G., & Obokoh, L. O. (2025). Integrating Indigenous Financial Frameworks in Zimbabwean Banks: A Decolonial Economics’ Approach to Sustainable Finance. Economies, 13(12), 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13120343