The Role of Institutional Quality in Chinese Outward Foreign Direct Investment and Domestic Investment’s Impact on Economic Stability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

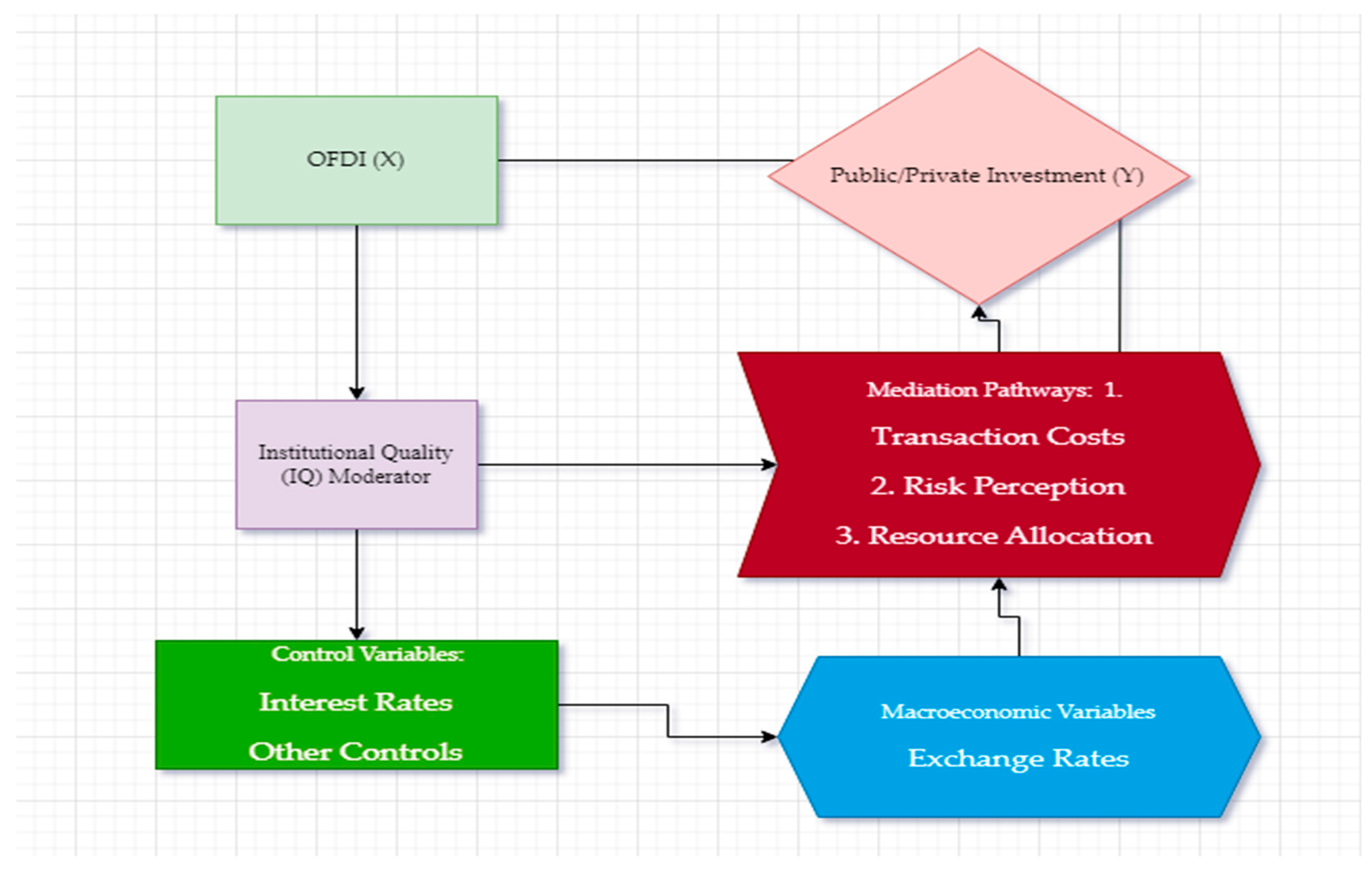

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodology and Data

Methodology

3.2. Data

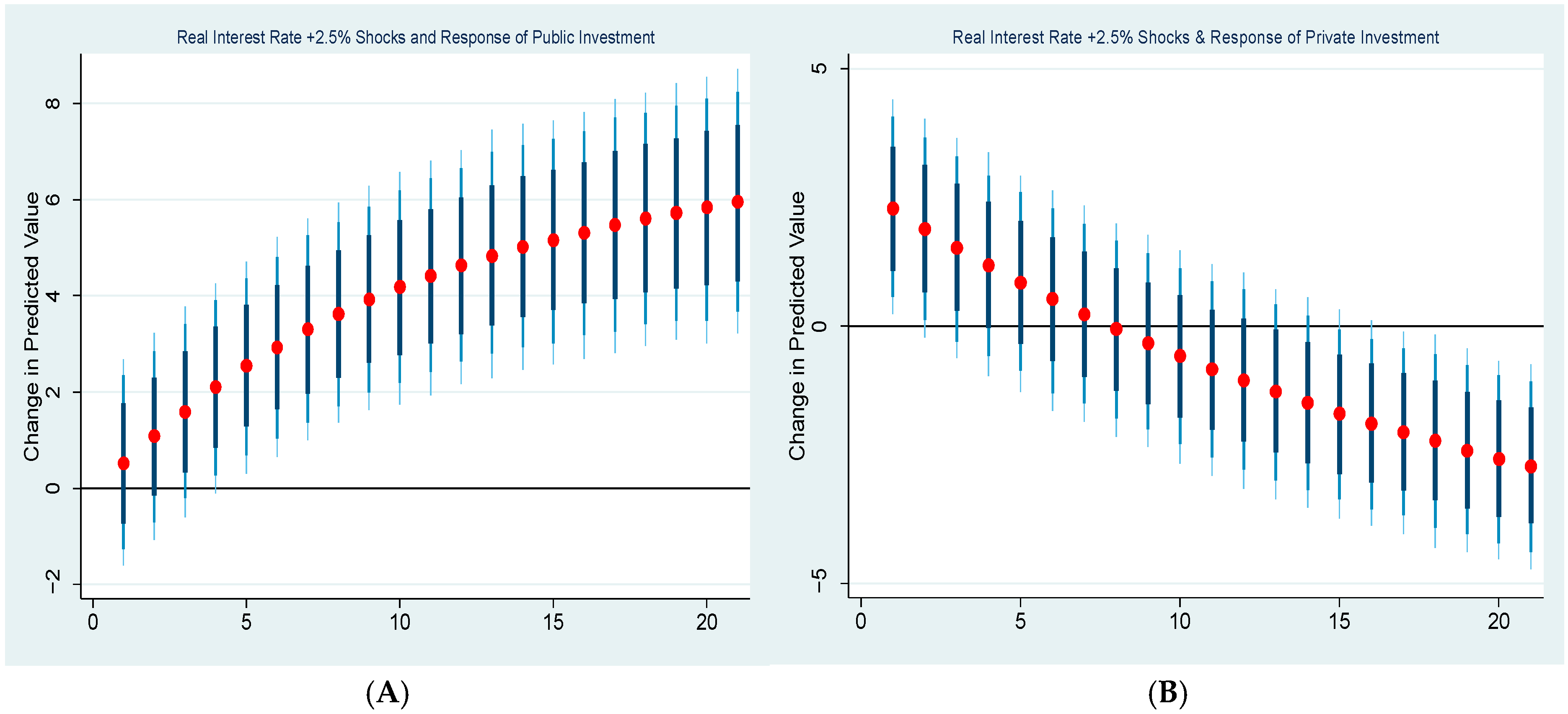

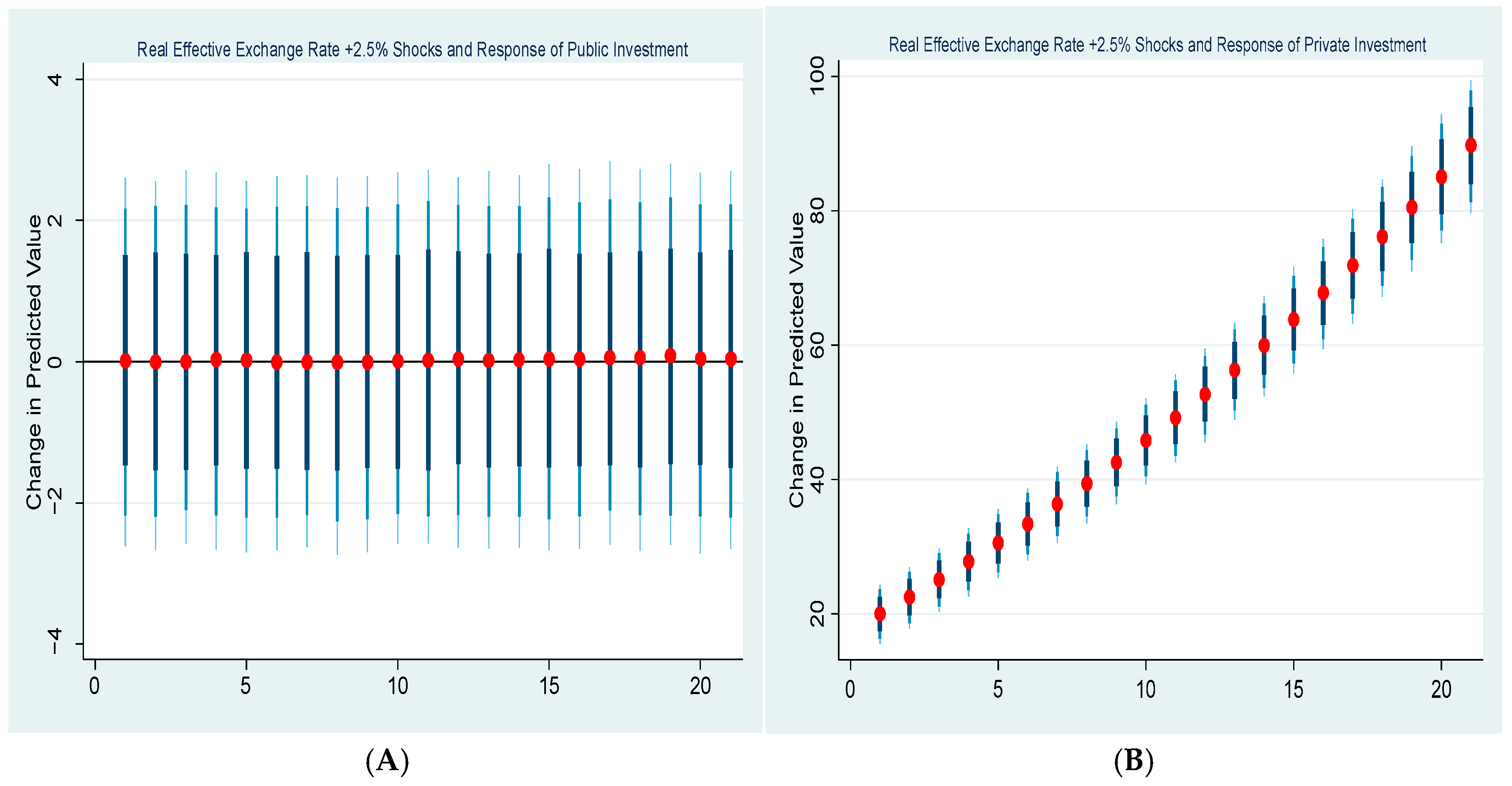

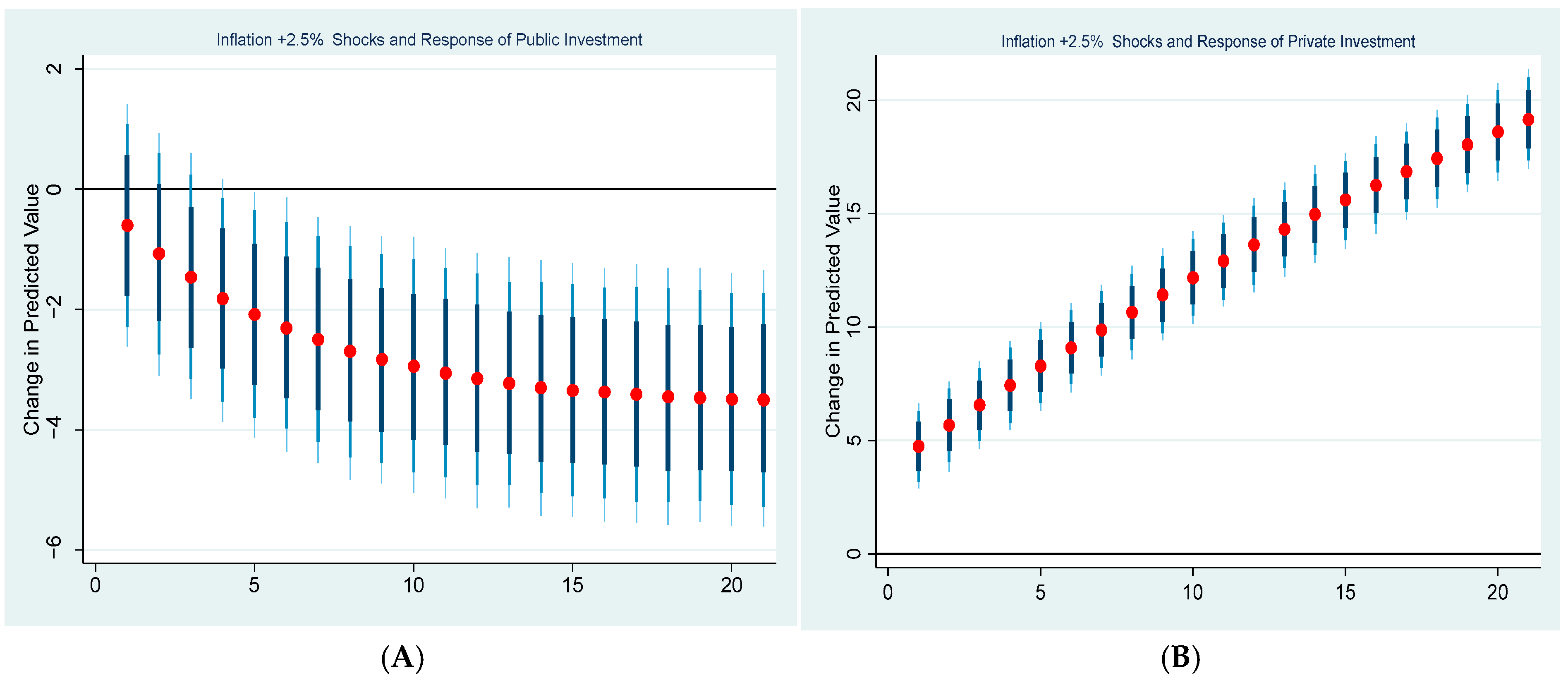

4. Empirical Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.2. Results

- OFDI and Macroeconomic Factors response to Public and Private Investment

- 2.

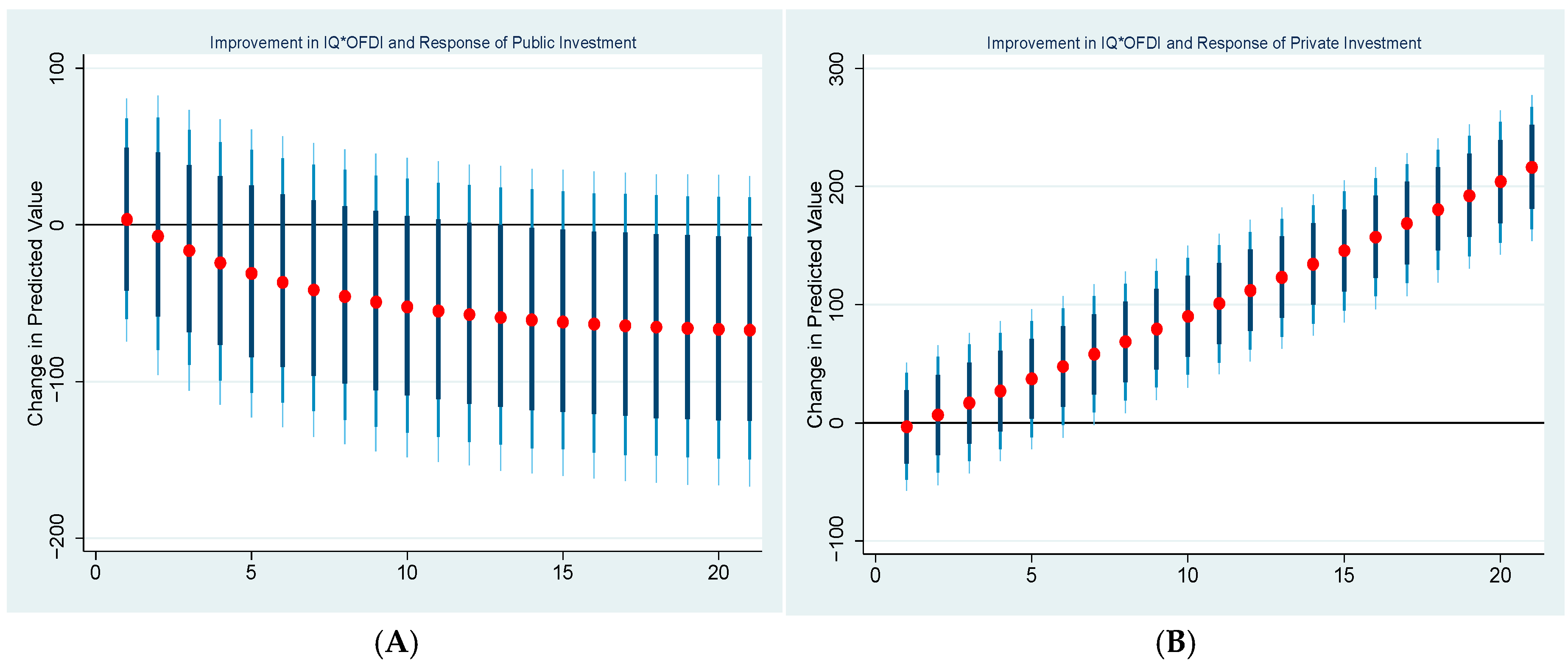

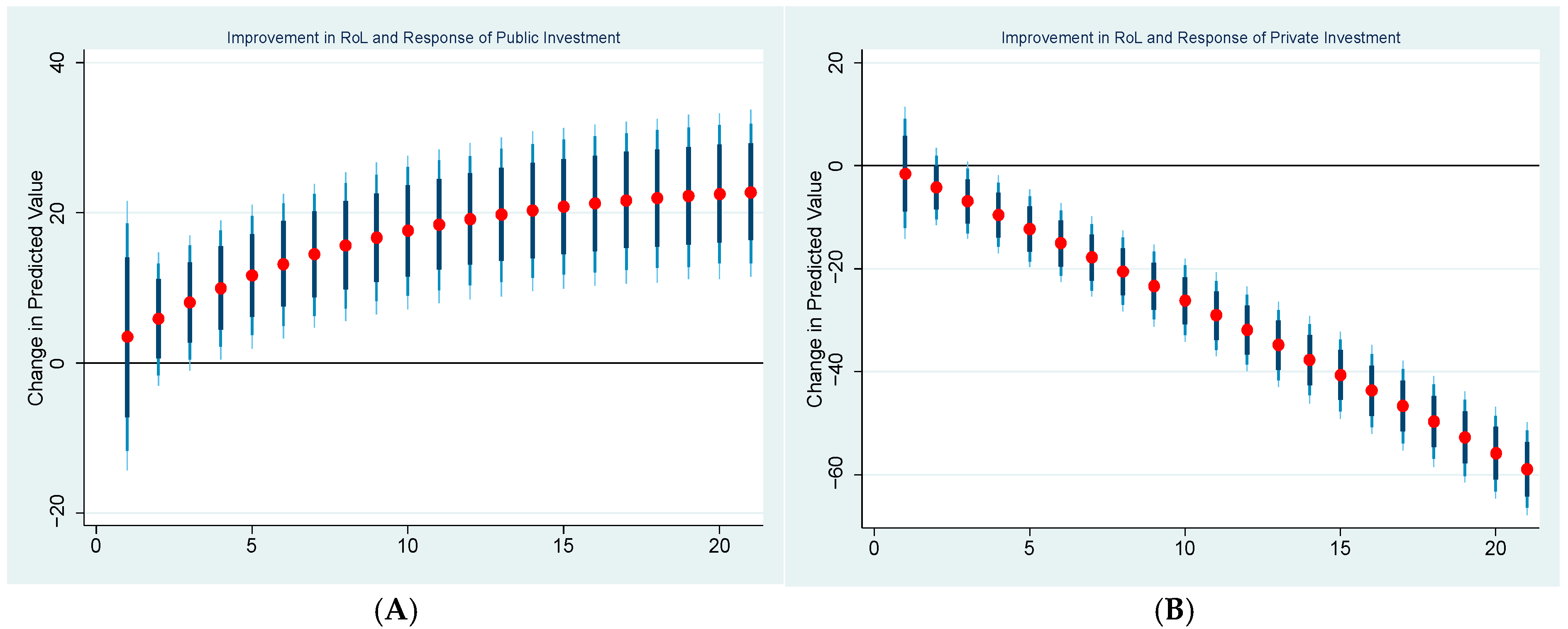

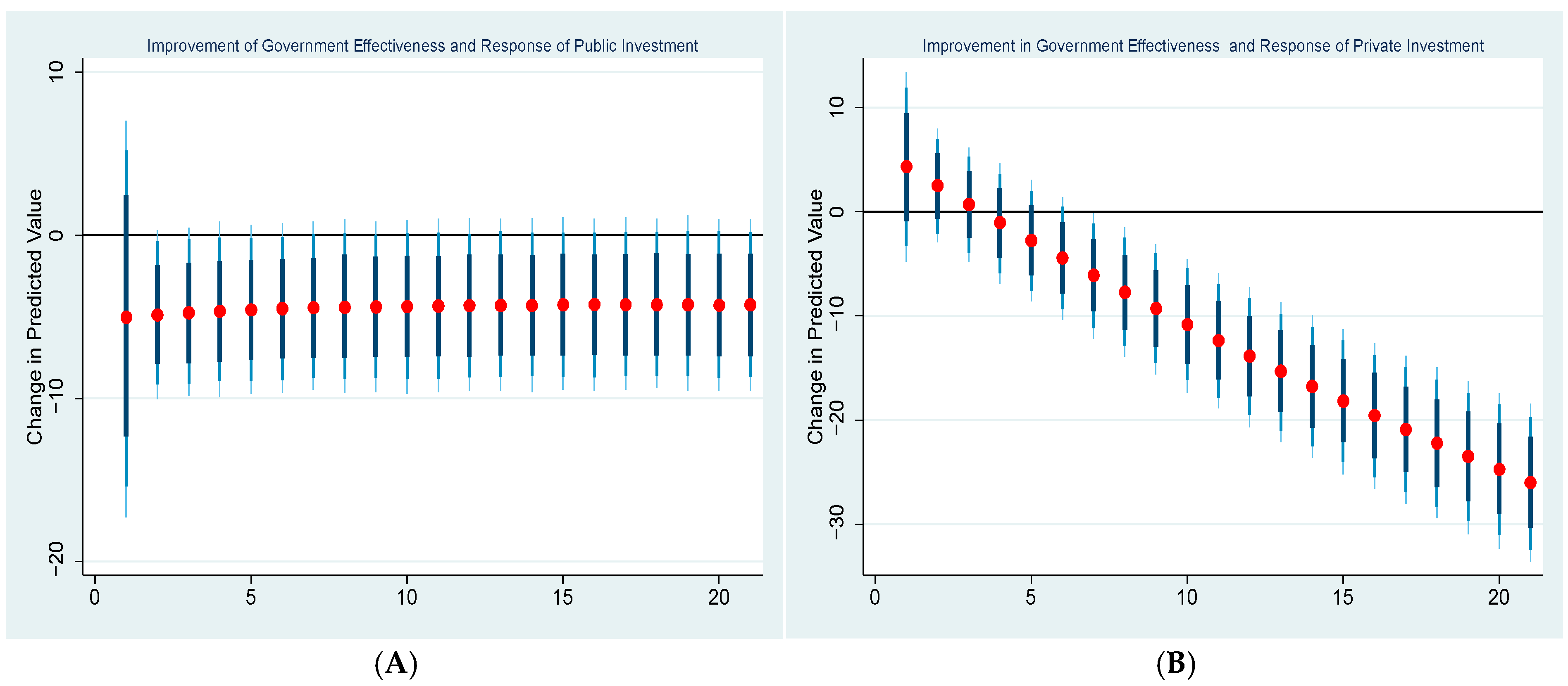

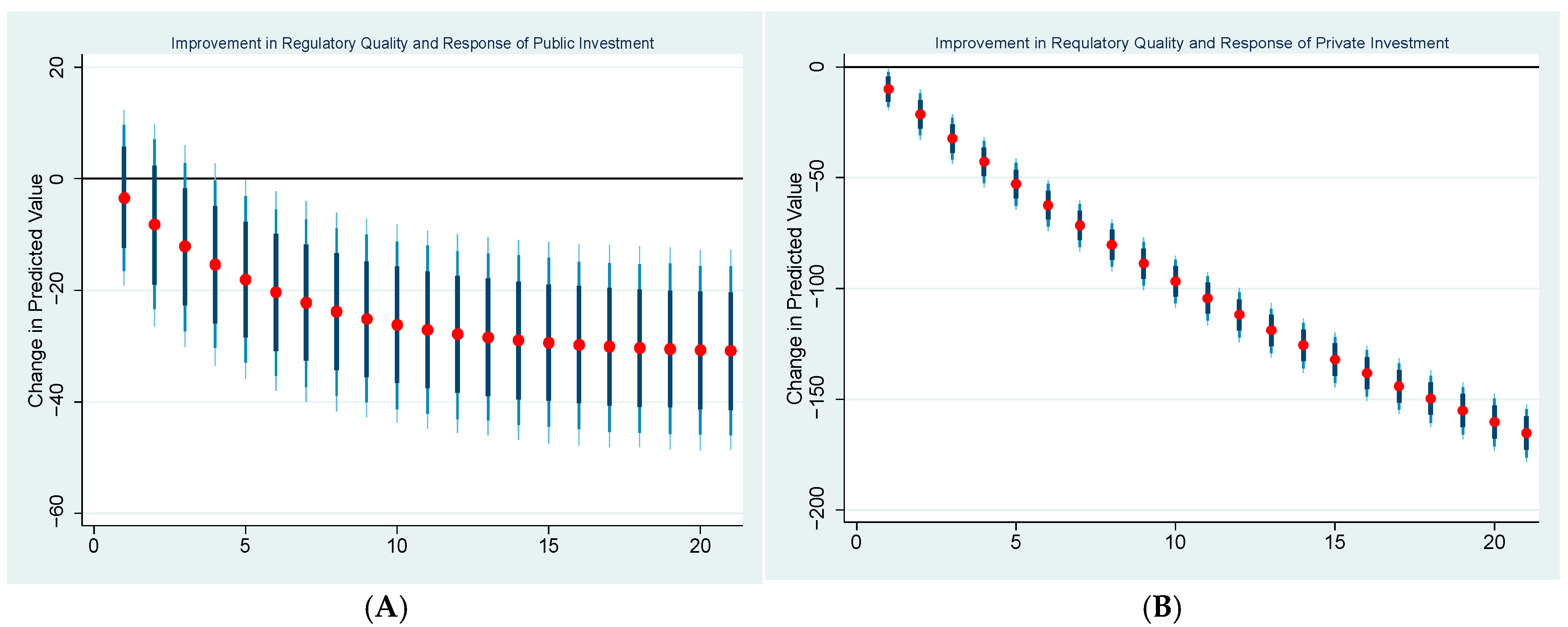

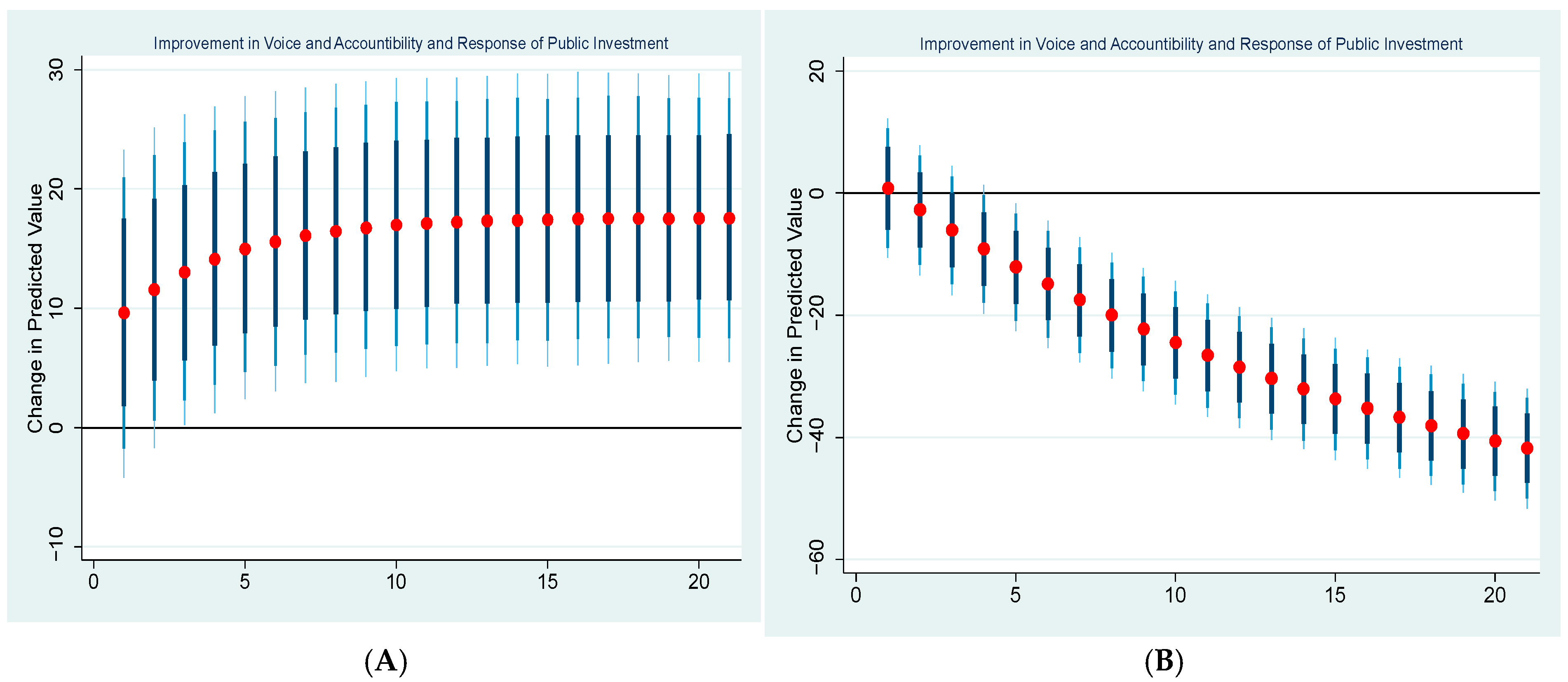

- OFDI and Institutional Factors response to Public and Private Investment

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Form |

| OFDI | Outward Foreign Direct Investment |

| DI | Domestic Investment |

| DCF | Domestic Capital Formation |

| PRI | Private Investment |

| PUBI | Public Investment |

| IQ | Institutional Quality |

| CoC | Control of Corruption |

| RoL | Rule of Law |

| G.E. | Government Effectiveness |

| R.Q. | Regulatory Quality |

| P.S. | Political Stability |

| V.A. | Voice and Accountability |

| ARDL | Autoregressive Distributed Lag |

| DS-ARDL | Dynamic Simulated ARDL |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| GDPPCG | GDP per Capita Growth |

| EXCH | Exchange Rate |

| RIR | Real Interest Rate |

| REER | Real Effective Exchange Rate |

| CS-ARDL | Cross-Sectional ARDL |

| MNCs | Multinational Corporations |

| BRI | Belt and Road Initiative |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| GCC | Gulf Cooperation Council |

References

- Ali, U., & Wang, J. J. (2018). Does outbound foreign direct investment crowd out domestic investment in China? Evidence from time series analysis. Global Economic Review, 47(4), 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sadiq, M. A. J. (2013). Outward foreign direct investment and domestic investment: The case of developing countries. International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Ameer, W., Sohag, K., Xu, H., & Halwan, M. M. (2020). The impact of OFDI and institutional quality on domestic capital formation at the disaggregated level: Evidence for developed and emerging countries. Sustainability, 12(9), 3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameer, W., Sohag, K., Zhan, Q., Shah, S. H., & Yongjia, Z. (2025). Do financial development and institutional quality impede or stimulate the shadow economy? A comparative analysis of developed and developing countries. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 12(1), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameer, W., Xu, H., & Alotaish, M. S. M. (2017). Outward foreign direct investment and domestic investment: Evidence from China. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 30(1), 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, P. S., & Hainaut, P. (1998). Foreign direct investment and employment in the industrial countries (Vol. 61). Bank for International Settlements, Monetary and Economic Department. [Google Scholar]

- Choy, L. H., Ho, W. K., & Mak, S. W. (2011, September 23–25). On FDI and domestic capital stock: A panel data study of Chinese regions. 16th International Symposium on Advancement of Construction Management and Real Estate, CRIOCM 2011, Chongqing, China. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, M. A., Foley, C. F., & Hines, J. R., Jr. (2005). Foreign direct investment and the domestic capital stock. American Economic Review, 95(2), 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durani, F., Ameer, W., Meo, M. S., & Husin, M. M. (2021). Relationship between outward foreign direct investment and domestic investment: Evidence from GCC countries. Asian Economic and Financial Review, 11(4), 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z., Zhang, R., Liu, X., & Pan, L. (2016). China’s outward FDI efficiency along the belt and road: An application of stochastic frontier gravity model. China Agricultural Economic Review, 8(3), 455–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldstein, M. (1995). The effects of outbound foreign direct investment on the domestic capital stock (No. 4668). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Globerman, S., & Shapiro, D. M. (1999). The impact of government policies on foreign direct investment: The Canadian experience. Journal of International Business Studies, 30, 513–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, S. K., & Wong, K. N. (2014). Could inward FDI offset the substitution effect of outward FDI on domestic investment? Evidence from Malaysia. Prague Economic Papers, 23(4), 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejazi, W., & Pauly, P. (2003). Motivations for FDI and domestic capital formation. Journal of International Business Studies, 34, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzer, D. (2008). The long-run relationship between outward FDI and domestic output: Evidence from panel data. Economics Letters, 100(1), 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzer, D., & Schrooten, M. (2008). Outward FDI and domestic investment in two industrialized countries. Economics Letters, 99(1), 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, E., & Sun, L. (2006). Dynamics of internationalization and outward investment: Chinese corporations’ strategies. The China Quarterly, 187, 610–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W. C., Wang, C., & Clegg, J. (2015). The effects of outward foreign direct investment on fixed-capital formation at home: The roles of host location and industry characteristics. Global Economic Review, 44(3), 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Country Risk Guide (ICRG). (2018). Country risk ratings and analysis. The PRS Group. [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2024). Fisacl monitor: Addressing the fiscal challenges of the global economy. Fiscal Affairs Department. [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund, Fiscal Affairs Department. (2025). Fiscal monitor [Data set]. Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/FM (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Jordan, S., & Philips, A. Q. (2018). Dynamic Simulation and Testing for Single-Equation Cointegrating and Stationary Autoregressive Distributed Lag Models. R Journal, 10(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. S., & Reinhart, C. M. (1990). Private investment and economic growth in developing countries. World Development, 18(1), 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, O., & Udomkerdmongkol, M. (2012). Governance, private investment and foreign direct investment in developing countries. World Development, 40(3), 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, P. K. (2005). The saving and investment nexus for China: Evidence from cointegration tests. Applied Economics, 37(17), 1979–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. J. (2001). Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16(3), 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauramo, P. (2008). Does outward foreign direct investment reduce domestic investment? Macro-evidence from Finland. (Working Paper No. 239). Palkansaajien tutkimuslaitos. [Google Scholar]

- Sauvant, K. P. (2008). Outward FDI from emerging markets: Some policy issues. Foreign Direct Investment, Location and Competitiveness, 2, 279. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, G. V., & Lipsey, R. E. (1992). Interactions between domestic and foreign investment. Journal of International Money and Finance, 11(1), 40–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uneze, C. U. (2013). Socio-economic determinants of savings in cooperatives by farmers of selected agricultural group lending schemes in Anambra state, Nigeria. Greener Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 3(5), 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (2017). World investment report. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2024). World development indicators. Available online: http://databank.worldbank.org/data/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- World Bank. (2025). World Development Indicators (WDI) [Data set]. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- You, K., & Solomon, O. H. (2015). China’s outward foreign direct investment and domestic investment: An industrial level analysis. China Economic Review, 34, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Public Investment (%GDP) | Private Investment (%GDP) | OFDI (%GDP) | DI (%GDP) | Gross Domestic Savings (% of GDP) | GDP Growth (Annual %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 18.76 | 5.21 | 0.24 | 37.54 | 39.95 | 9.92 |

| 1997 | 19.09 | 5.43 | 0.39 | 35.52 | 40.35 | 9.23 |

| 1998 | 21.64 | 5.82 | 0.43 | 34.81 | 39.54 | 7.84 |

| 1999 | 21.30 | 6.05 | 0.36 | 34.10 | 37.42 | 7.66 |

| 2000 | 20.34 | 6.90 | 0.38 | 33.57 | 36.42 | 8.49 |

| 2001 | 20.27 | 8.11 | 0.72 | 35.54 | 38.06 | 8.33 |

| 2002 | 19.63 | 9.63 | 0.42 | 36.15 | 39.01 | 9.13 |

| 2003 | 20.37 | 11.79 | 0.50 | 39.62 | 41.97 | 10.03 |

| 2004 | 19.74 | 13.39 | 0.40 | 41.84 | 44.76 | 10.11 |

| 2005 | 18.56 | 14.87 | 0.60 | 40.34 | 45.61 | 11.39 |

| 2006 | 16.99 | 16.55 | 0.86 | 40.93 | 47.42 | 12.72 |

| 2007 | 15.77 | 17.76 | 0.48 | 41.46 | 49.00 | 14.23 |

| 2008 | 15.95 | 18.61 | 1.23 | 43.27 | 50.22 | 9.65 |

| 2009 | 18.70 | 20.64 | 0.86 | 46.44 | 49.91 | 9.39 |

| 2010 | 17.66 | 21.50 | 0.95 | 47.61 | 51.08 | 10.63 |

| 2011 | 15.39 | 24.06 | 0.64 | 47.69 | 49.84 | 9.55 |

| 2012 | 15.17 | 25.59 | 0.76 | 47.23 | 48.85 | 7.86 |

| 2013 | 15.04 | 26.58 | 0.76 | 47.39 | 48.28 | 7.76 |

| 2014 | 14.73 | 27.08 | 1.57 | 47.01 | 47.47 | 7.42 |

| 2015 | 15.31 | 28.14 | 1.92 | 45.40 | 46.00 | 7.04 |

| 2016 | 16.70 | 28.16 | 1.12 | 42.63 | 44.96 | 6.84 |

| 2017 | 17.26 | 28.28 | 1.02 | 43.01 | 45.13 | 6.94 |

| 2018 | 16.98 | 29.90 | 1.12 | 43.79 | 44.94 | 6.74 |

| 2019 | 17.33 | 30.20 | 0.95 | 43.25 | 43.98 | 5.95 |

| 2020 | 16.98 | 28.28 | 1.04 | 43.36 | 44.66 | 2.23 |

| 2021 | 17.26 | 29.90 | 1.00 | 43.14 | 46.07 | 8.44 |

| Variable Category | Variable/Path | Relationship |

|---|---|---|

| Independent Var. | OFDI | Direct effect on public/private investment (Y). |

| Dependent Var. | Public/Private Investment | Outcome variable influenced by OFDI, IQ, and controls. |

| Moderator | Institutional Quality (IQ) | Moderates OFDI’s effect via: |

| 1. Transaction costs ↓ | ||

| 2. Risk perception ↓ | ||

| 3. Resource allocation efficiency ↑ | ||

| Control Vars. | Macroeconomic Factors: | Adjust for confounding effects: |

| Interest Rates | Cost of capital → Investment decisions. | |

| Exchange Rates | OFDI profitability/risk → Investment flows. |

| Variables | Description of Variables | Theoretical Justification | Source of Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|

| OFDI | Outbound foreign direct investment | OFDI influences DCF by various channels. First Channel through which OFDI enhances DCF if it is financed by ample savings and excessive foreign reserves of a country (Stevens & Lipsey, 1992). | World Development Indicators, World Bank (World Bank, 2024) |

| DCF | Domestic investment (DI) | We decomposed DCF into public and private investment as neo-classical economist believe that public and private capital crowd out each other and aggregating them into one composite measure may result in DCF aggregation bias (Khan & Reinhart, 1990; Morrissey & Udomkerdmongkol, 2012; Narayan, 2005). | World Development Indicators, World Bank (World Bank, 2024) |

| PRI | Private investment | PRI absorbs economic shocks and stabilizes the economy. Private capital is more resilient, active, and productive than public capital investment. Overall, impact of OFDI on private capital is quite productive in an economy (Khan & Reinhart, 1990). | Fiscal Affairs Department, International Monetary Fund (International Monetary Fund [IMF], 2024) |

| PUBI | Public investment | PUBI is considered to be less effective in promoting OFDI. Generally, higher PRI means less PUBI and more OFDI | Fiscal Affairs Department, International Monetary Fund (International Monetary Fund [IMF], 2024) |

| IQ | Institutional quality | IQ is the driving factor that enhances private investment in developed countries and it reduces economic cost of business transactions in an economy (Ameer et al., 2020). Therefore, the net effect is going to decide whether IQ is going to increase OFDI or decrease it (Globerman & Shapiro, 1999). Institutional quality (IQ) is measured using the ICRG dataset, where a higher value reflects better institutional performance. A negative value indicates weaker institutional quality, where lower scores suggest higher corruption, a weaker rule of law, and other factors that impede the business environment. Hence, a negative IQ value signifies suboptimal institutional conditions that can reduce the effectiveness of policies aimed at promoting domestic investment. | ICRG dataset (2024) (International Country Risk Guide [ICRG], 2018) |

| OFDI × IQ | Interactive variable of OFDI and IQ | OFDI is supposed to produce better results in the presence of quality institutions and thus, in turn, promotes economic development in a country (Ameer et al., 2020). | Authors’ calculation |

| GDPG | GDP growth | High GDP growth is a reflection of growing domestic income and investment. High income increases outbound investment (Uneze, 2013) | World Development Indicators, World Bank (World Bank, 2024) |

| EXCH | Exchange rate | A favorable exchange rate encourages investors in developed countries to invest abroad. But on the other hand, favorable exchange rates deter exports which can possibly affect domestic capital formation. | World Development Indicators, World Bank (World Bank, 2024) |

| INTEREST | Interest rate | Investment of funds abroad in the form of overseas investment may result in rise of interest rate of domestic borrowings that makes DI more difficult (Goh & Wong, 2014). | World Development Indicators, World Bank (World Bank, 2024) |

| INFLATION | Inflation rate | A healthy level of inflation promotes investment and economic stability in an economy (Ameer et al., 2020). | World Development Indicators, World Bank (World Bank, 2024) |

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Investment | 26 | 17.81032 | 2.04721 | 14.7389 | 21.646 |

| Private Investment | 26 | 18.79041 | 9.12028 | 5.2109 | 30.201 |

| FDI Outflow | 26 | 0.803843 | 0.40179 | 0.24474 | 1.926 |

| Institutional Quality | 26 | −0.49789 | 0.10125 | −0.6217 | −0.273 |

| Real Interest Rate | 26 | 2.66561 | 2.71185 | −2.3056 | 7.356 |

| Real Effective Exchange | 26 | 103.8341 | 15.0102 | 84.920 | 130.044 |

| Inflation | 26 | 3.051691 | 2.82261 | −1.2630 | 8.0756 |

| Variables | PI | PRI | FDI_O | RIR | REER | INF | IQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PI | 1 | ||||||

| PRI | 0.539 ** | 1 | |||||

| FDI_O | 0.325 * | 0.486 * | 1 | ||||

| RIR | 0.144 | −0.233 | −0.402 | 1 | |||

| REER | −0.291 | −0.121 | −0.265 | 0.382 | 1 | ||

| INF | −0.197 | −0.392 | −0.328 | 0.515 ** | 0.631 ** | 1 | |

| IQ | 0.428 * | 0.389 * | 0.318 * | −0.301 | −0.124 | −0.411 * | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ameer, W.; Aziz, A.L.; Ali, M.; Fahlevi, M.; Propheto, A. The Role of Institutional Quality in Chinese Outward Foreign Direct Investment and Domestic Investment’s Impact on Economic Stability. Economies 2025, 13, 344. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13120344

Ameer W, Aziz AL, Ali M, Fahlevi M, Propheto A. The Role of Institutional Quality in Chinese Outward Foreign Direct Investment and Domestic Investment’s Impact on Economic Stability. Economies. 2025; 13(12):344. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13120344

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmeer, Waqar, Aulia Luqman Aziz, Muhammad Ali, Mochammad Fahlevi, and Arfendo Propheto. 2025. "The Role of Institutional Quality in Chinese Outward Foreign Direct Investment and Domestic Investment’s Impact on Economic Stability" Economies 13, no. 12: 344. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13120344

APA StyleAmeer, W., Aziz, A. L., Ali, M., Fahlevi, M., & Propheto, A. (2025). The Role of Institutional Quality in Chinese Outward Foreign Direct Investment and Domestic Investment’s Impact on Economic Stability. Economies, 13(12), 344. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies13120344