1. Introduction

Digital technology and infrastructure have pervaded both private and professional spheres becoming strategic funding areas and challenges for EU space with a particular focus on administrative services aimed to increase efficiency of public management and foster, in a more effective manner, European integration (

Febiri et al., 2024;

European Commission, 2025).

Digital transformation in public administration is becoming a defining tool for modernizing governance and enhancing the efficiency of public services in the contemporary era. According to

Asgarkhani (

2005), digital governance represents a mechanism for reforming public management and a strategic instrument for reducing the digital divide. Modern systems allow the automation of routine tasks, improve operational efficiency, and facilitate faster and more secure interactions between citizens and authorities (

Mountasser & Abdellatif, 2023). However, the transition from traditional systems generates complex challenges.

Irani et al. (

2023) show that the success of digital transformation depends on understanding existing technological infrastructures, institutional policies, and the socio-administrative context in which the systems operate. Digital accessibility and connectivity is considered one of the top priorities of EU policies for rural areas directly affecting their development strategies (

European Union, 2025).

Romania’s experience highlights both the potential and the limitations of digital governance. Specifically, research indicates that the digitalization of Romanian public administration has increased transparency, accessibility, and administrative efficiency. However, significant disparities persist between urban and rural areas (

Dumitrescu, 2024). As digital tools are increasingly adopted, they can change the way local authorities plan, communicate, and implement public policies, fostering civic engagement and participatory governance (

Vlad et al., 2023).

Nevertheless, integration of digital services into local administrative processes remains uneven, necessitating the development of standardized frameworks to assess digital maturity levels. Scientific literature identifies several barriers to building an equitable and efficient digital administration. Legislative constraints, a lack of harmonization in administrative procedures, and staff resistance to change hinder the implementation of digital strategies (

Kuhlmann & Heuberger, 2023). Additionally, citizens’ access to digital services is uneven, and differences in digital skills, internet connectivity, or acquisition of digital devices create inequalities that can reinforce existing gaps (

Pakhnenko & Kuan, 2023). This phenomenon is particularly evident among vulnerable social groups, shaped by both endogenous and exogenous factors of social segregation within Bucharest’s urban landscape (

E. Matei et al., 2013;

Mareci et al., 2023). From the citizens’ perspective, the efficiency of digital administration is often evaluated through institutional performance and the functionality of automated processes, overlooking the real user experience and level of engagement (

Esko & Koulu, 2023;

Geraci et al., 2013).

This situation underscores the need for analytical frameworks that encompass institutional capacity and active citizen participation. To provide a suitable context for further investigation, the peri-urban areas surrounding Bucharest, including Berceni, Cernica, Chiajna, Clinceni, Dobroești, Domnești, Glina, Jilava, Mogoșoaia, Tunari, and Vidra, offer a compelling case for analyzing the digital maturity of local administrations. These communities lie at the interface between urban and rural environments, benefiting from proximity to metropolitan resources while facing limitations specific to rural or small urban administrations. The peri-urban–rural–suburban relationship is an essential component of Romania’s integrated territorial development strategy, reflecting the functional, economic, and social links between cities and their surrounding settlements (

Markuske, 2024). Peri-urban and suburban areas, located at the interface between urban and rural environments (

Cavailhès et al., 2004;

Sârbu, 2005), are undergoing rapid expansion and transformation, becoming increasingly dependent on urban infrastructure and services. At the same time, the rural environment surrounding cities contributes to socio-economic balance through agricultural resources, labor, and cultural identity (

Hesse & Siedentop, 2018) and absorbs both demographic movement and economic relocation as outcomes of the exurbanization phenomenon (

Nelson & Dueker, 1990), which also currently extends to post-communist societies and Bucharest metropolitan area (

Săgeată et al., 2025).

Building on this context, this study develops a standardized framework for assessing minimum digital maturity, which can serve as a reference tool and be further expanded. Digital maturity is evaluated across four main domains: (1) the functionality of institutional websites; (2) the digitalization of public services; (3) digital communication and information; (4) social media engagement. The analyzed indicators include response times and mobile optimization of municipal websites, availability of payment platforms and online applications, feedback mechanisms and transparency of public projects, as well as active use of social media channels. Each indicator is assigned a weight within an evaluation system that totals 100 points.

The methodology addresses four main questions: (1) how the presence and quality of institutional web pages are reflected, including mobile optimization; (2) what are the most common digital public services provided at the local level; (3) to what extent citizens participate in administrative communication and the promotion of transparency; and (4) to what extent social media is integrated into local governance.

Our approach provides a reference point for the digital maturity of peri-urban localities around Bucharest, contributing to the debate on urban and rural development through access to digital services. In doing so, the results inform decision-makers, local authorities, and researchers about the minimum conditions required for effective digital governance and identify opportunities to expand digital services, thereby increasing citizen engagement and local development.

Introducing a unique perspective to the analysis of local administrations, the research establishes a clear set of indicators to assess the minimum digital maturity. Previous research has focused on general descriptions, best practices and case studies (

Irani et al., 2023), simple empirical quantitative (

A. Matei & Matei, 2012) or qualitative evaluations (

A. Matei & Gaita, 2015;

Lutsenko, 2024). However, based on our review of the literature, we have not identified any definition of a minimum standard that is systematically applicable, particularly in the context of Eastern Europe. Starting from simple and broadly applicable criteria, the research provides therefore a coherent framework for comparing localities with one another and for monitoring digital progress over time. The methodological approach is highly transferable, allowing the tools to be applied in other territories or regions regardless of administrative size or structure. In this way, the study provides a concrete reference point for evaluating digitalization, which other researchers or local authorities can adopt, adapt, and build upon filling an applicative science gap and providing a tool for further research and analysis. The study aims to explore how prepared local administrations in the peri-urban area of Bucharest are for the digital era and to demonstrate how differences in their use of technology can influence institutional transparency, the quality of public services, communication with citizens, and people’s engagement in community life.

3. Methodology

3.1. The Case Study

Post-communist period brought important societal changes, also reflected in rural communities once with the radical post-economic restructuring that triggered massive population decline (

Dragan et al., 2024) and important deindustrialization processes for entire regions where both urban and rural populations depended on various industries (e.g., mining) (

Rîșteiu et al., 2022). The mass privatization and in-depth economic restructuration had obvious negative consequences determining severe structural unemployment and important migrations from rural regions to both urban areas and more attractive and accessible regions in Romania or abroad (

Vasilcu, 2002). The free movement of people, including for leisure purposes and the important development of service industries particularly oriented rural areas which displayed important natural and/or cultural resources towards hospitality sector (

Lequeux-Dincă & Preda, 2018).

The peri-urban space of Bucharest is dominated by rural communities; thus, this study will provide a broader perspective on this environment, which is more strained than small urban areas regarding the changes generated by the central urban hub (

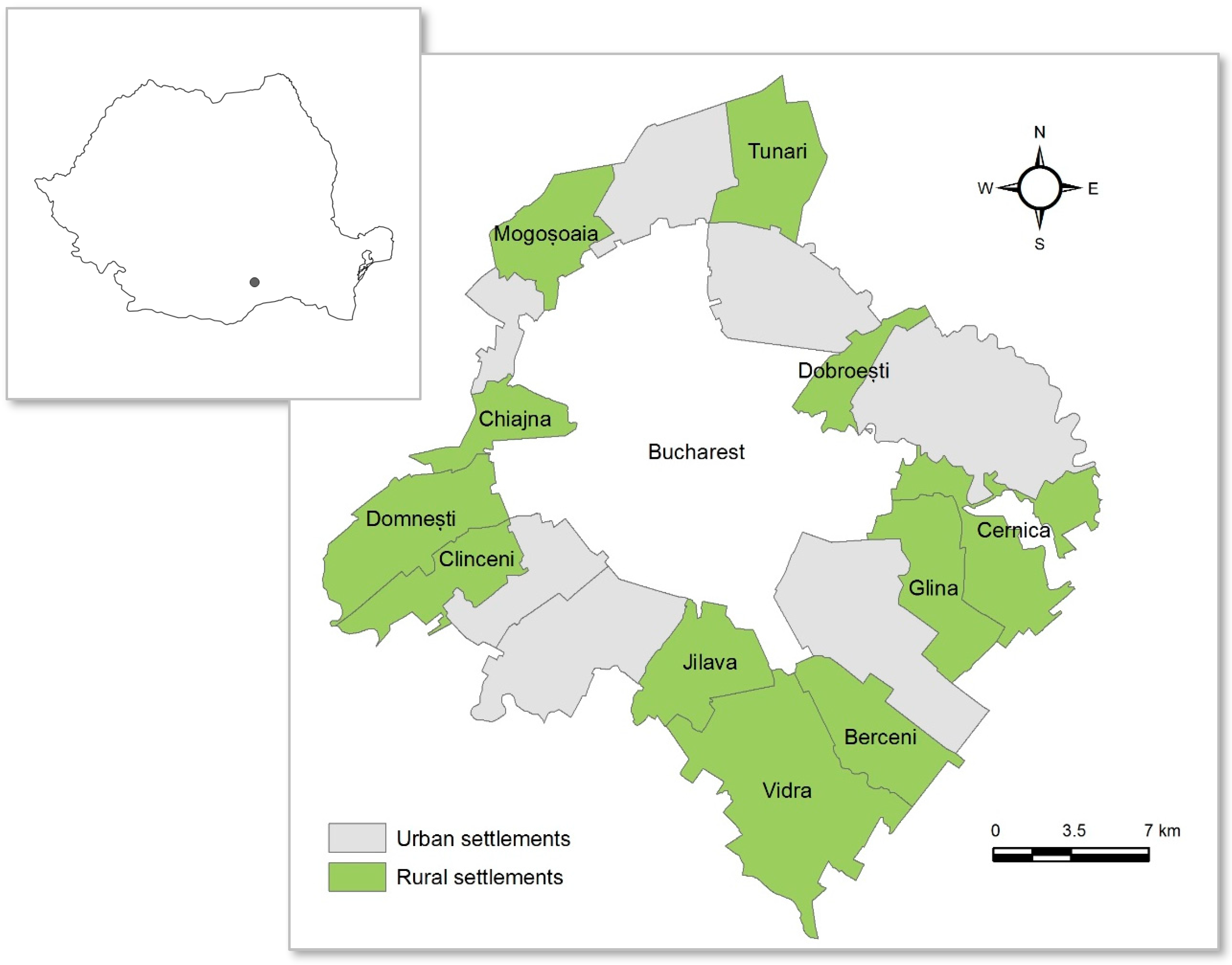

Figure 1). When defining and delimiting the study area, we referred to theoretical concepts as described in reference studies (

Cavailhès et al., 2004;

Sârbu, 2005;

Markuske, 2024;

Săgeată et al., 2025).

Peri-urban area—marks the transition zone between urban and rural areas, characterized by mixed development (housing, agriculture, light industry) and high urban expansion dynamics.

Suburban area—represents the territory in the immediate vicinity of the city, functionally integrated into it, often intended as a place of residence for the urban working population.

Rural area—is a predominantly agricultural space, with low population density and less developed infrastructure.

Migration flows and urbanization process determining rising prices and congestion in cities are driving the population to the suburbs, leading to peri-urban expansion and the transformation of rural space nearby as happened also in the case of Bucharest capital city (

Kurek et al., 2015;

Preda et al., 2022).

In

Figure 1, both rural and urban peri-urban settlements located in the first ring around Bucharest can be distinguished. Our case study is represented by the fragmented rural area surrounding Bucharest urban agglomeration.

If referring to the current state of Romania’s digitization in the public administration on the other hand the need of increasing citizens participation in administrative communication and the promotion of transparency of public digital services was broadly remarked in numerous official documents (

SNDCIDR, 2024). Based on reference data sources (Eurostat) reports underscored important discrepancies for both digital infrastructure capacities (with certain rural regions displaying VHCN coverage below the EU average) and digital competences for Romanian citizens between the urban and rural areas (

Ministerul Cercetării, Inovării și Digitalizării, 2025). However, the market competition dynamics and, in part, public intervention, including market regulation and publicly funded projects (e.g., RoNet) led to a very good, fixed internet connectivity and internet speeds up to 10 Gbps available for many rural settlements in Romania. Rural areas lagging in terms of digitalization are usually the less populated ones as depopulated and mainly also less accessible settlements are found financially unattractive by operators (

Ministerul Cercetării, Inovării și Digitalizării, 2025).

Modernization of Romania’s public administration is driven by strategic projects aimed at transforming infrastructure, interoperability, and digital capabilities. Implementing the Government Cloud infrastructure and migrating applications and IT systems to the cloud (MAS IC) establishes a scalable administrative architecture, while Automating Work Processes streamlines internal workflows, and Advanced Technology Skills for SMEs strengthens the digital capacity of the economic sector. The National Interoperability Platform (PNI) and High-Performance Administration Through Advanced Technologies (APTA) enhance institutional integration and digital connectivity, while initiatives for strengthening administrative capacity and the Genomic Data Infrastructure lay the groundwork for intelligent, resilient, and future-oriented governance.

3.2. Methodological Framework

This study aimed to design a methodological framework and conduct a comparative analysis of differences in administrative digitalization across the peri-urban areas of Bucharest. The selected sample included communes forming the first ring surrounding the capital city of Romania. Our analysis covered the communes of Berceni, Cernica, Chiajna, Clinceni, Dobroești, Domnești, Glina, Jilava, Mogoșoaia, Tunari, and Vidra (

Suditu, 2023;

Petre, 2025).

To address the research questions, the paper introduces an evaluative index for digital administration, structured around four key variables that surpass and demonstrate variations in digital maturity among the settlements included in the case study and were inspired by studies mentioned in the above literature review chapter. These four variables are, in turn, composed of other basic variables which represent the operationalization of elements of public administration web functionality, digital public services availability, main communication and information tools, including social media elements. Basic variables were selected after web analysis performed by the authors of the current study, discussions with administration representatives, consultation of official strategies, reports and existing literature review on the topic, synthesized in the above chapter.

Data analysis involved calculating scores for each indicator based on points assigned to sub-indicators. These scores were aggregated to obtain a final digitalization score for each settlement. The results reveal differences between localities and highlight specific areas where peri-urban administrations can improve digital accessibility, beyond the variations observed across the main variables.

The first indicator, focusing on

institutional web functionality, analyzed the existence of the town hall official website, its response time, optimization for both desktop and mobile navigation, and the search function. As also confirmed by other studies quoted above (

Esko & Koulu, 2023;

Geraci et al., 2013), these elements are crucial for ensuring information accessibility and facilitating the initial interaction between citizens and the administration.

The second indicator refers to the

digitalization of public services, including as sub-variables the possibility of online appointment scheduling, payment of taxes through digital platforms, access to standardized online forms, response time between the authority and the citizen, and the existence of online contacts with municipal employees or departments. Our evaluation focused on the availability of services and the efficiency of digital communication. A test by

Region Västerbotten (

2014) from Sweden reflected how local administrations manage citizen interactions through digital channels.

The third indicator addressing the

enhancement of the digital information and communication experience, analyzed the existence of online feedback questionnaires and of complaint systems, transparency of public projects, the existence of an updated digital calendar of public-interest events, and the possibility of submitting petitions online. These sub-indicators provide an overview of the extent to which town halls facilitate citizen participation, transparent communication, and access to locally relevant information (

Hofmann et al., 2013;

Taylor et al., 2015).

The fourth indicator regarding communication via social media, assessed the presence of official social media pages, posting frequency over the last month, publication of council decisions and resolutions, and the existence of newsletters or official groups. This indicator reflects the local administration’s ability to maintain active and interactive communication with citizens using modern digital channels.

Data collection was conducted through direct online observation, which involved analyzing official websites and social media pages. Facebook was selected as a reference platform for social groups due to its widespread use and representative character. Each sub-indicator was evaluated based on both its presence and the frequency of updates.

Špaček (

2018) conducted a study on regional public administrations in the Czech Republic, where he concluded that local authorities use Facebook primarily as a one-way communication tool, from authorities to citizens, and only for certain types of information. The social media platform did not stand out as a public space for citizen deliberation. Scores were assigned according to parameters such as posting frequency, website response time, or availability of online functionalities.

3.3. Variables Validation and Weighting—Expert Input

The evaluation of digitalization was structured around the four main indicators and their corresponding sub-indicators, with a maximum total score of 100 points, as detailed in

Appendix A.

The selection and the weighting of the four main indicators followed a multiphase process grounded in both literature and expert consultations. The initial ranking and weighting of the variables were based on the authors’ expertise and judgement, informed by desk research and a review of relevant literature. This preliminary order was subsequently refined through consultations with a pool of experts recruited using convenience sampling, a method that enables the collection of essential expert input under conditions of limited time and human resources (

Golzar et al., 2022). The study ensured representativeness and minimized subjective bias through purposive sampling, as respondents were selected according to their professional background and specific expertise in territories with similar characteristics (rural settlements in metropolitan areas of large cities in Romania). The respondent’s sample required a minimum of five years of experience in peri-urban–rural metropolitan areas of large and mid-sized cities in Romania, excluding settlements included in our case study. Ultimately, a total sample of 15 experts was formed gradually by applying data saturation techniques, which greatly reduce the interviewed pool particularly for homogenous study populations (

Henrik & Kaiser, 2022), used for purposive sampling in qualitative research (

Bouncken et al., 2025). The main characteristics of the respondents’ sample are synthesized below (

Table 1) and show important coverage, variance and balance in terms of territorial representativeness (8 out of a total of 41 counties NUTS 3 regions belonging to 4 out of 8 NUTS2 regions) as well as high representativeness in terms of professional role played in administration.

The respondents answered two main questions regarding the rank order and relative weight of each of the four main variables in a hypothetical digital maturity index for administrative services, according to their perceived importance for digital administration (

Table 2 and

Table 3). Expert input led to adjustments of our initial estimations, resulting in a more balanced weighting of the index and the development of a more realistic model (

Appendix A). A greater weight was assigned to the first variable, which was consistently ranked first by most respondents (

Table 2), while the fourth variable, concerning administrative communication on social media platforms, remained in the same position, its weight was increased to match that of the third indicator (

Table A1,

Appendix A).

Expert consultation therefore played a central role in validating and adjusting weights, as well as for confirming the order of indicators. This process complemented the analysis, initially developed and motivated by the research team from a mainly theoretical view, with the one based on practical experience, justifying the use of uneven weighting and helping limit the researchers’ subjective bias on the method.

This approach also allowed considering possible regional or county-level differences and increasing the degree of objectiveness for the method through obtaining a broader pool of experts according to their territorial representativeness. The respondents were mainly mayors, vice-mayors, and county councilors. They represented rural, peri-urban, and metropolitan areas in Romania. These included large and very large cities in the South Development Region, such as the communes of Scoarța and Bălești in the peri-urban area of Târgu Jiu city; Alunu and Budești in the peri-urban area of Râmnicu Vâlcea; Găneasa and Ianca in the peri-urban area of Slatina; and Isalnița and Șimnicu de Sus in the metropolitan area of Craiova, the seventh largest city after Bucharest. The list also includes Valea Mare in the peri-urban area of Târgoviște and the commune of Blejoi in the peri-urban area of Ploiești. In the South-East Development Region, the communes of Corbu and Agigea represent the metropolitan area of Constanța, the fourth-largest city in Romania. In the North-East Development Region, county councilors represented the Iași metropolitan area, the third largest city in Romania after Bucharest. Our method reinforced the overall relevance of the model and its results, including their representativeness, generalizability, and transferability. The main outcome is a general methodological framework that can be transferred or adapted to other regions and may generate comparative results, at least for other territories in Romania or in Central and Eastern Europe.

Two types of data were collected during July–September 2025 period: (1) data for validating and adjusting methodological variables, and (2) input data for the model itself. Respondents were informed about their anonymized participation as experts with in situ experience in administrative services, which contributed to the validation and/or adjustment of preliminary theoretical results and estimations within our methodological framework. Informed oral consent was obtained prior to answering the questions, and their responses subsequently enriched our expert data pool.

4. Results

4.1. Institutional Website Functionality

The assessment of institutional web functionality revealed a fragmented and uneven digital presence, with each town hall appearing to have developed its own distinct online space, marked by varying levels of coherence, currency, and technical performance. While the analysis began verifying the existence of an official website, this presence was treated not as a binary condition but as a continuum reflecting the relationship between local administrations and the evolving digital dynamics of their communities.

In terms of the sub-indicator on website existence and updating, all eleven town halls maintain dedicated online platforms, yet the level of editorial activity differs considerably. Tunari received the lowest score of one point, as their rarely updated websites seem to function more as symbolic placeholders than as active communication tools. By contrast, Berceni, Chiajna, Clinceni, Glina, and Vidra scored five points, providing monthly updates that sustain a minimal but consistent flow of information. At the upper end, Cernica, Dobroești, Domnești, Jilava, and Mogoșoaia achieved the maximum score of ten points through weekly or more frequent postings, indicating an organizational culture that prioritizes timeliness and continuous communication. Beyond frequency, there was significant variation in website aesthetics and technical platforms, with each interface expressing a distinct institutional vision, ranging from color schemes to submenu structures, without adherence to a common model.

The sub-indicator on

initial page load time (

Figure 2) revealed a notable polarization. Tests conducted simultaneously at 10:00 p.m., when internet traffic is at its minimum, helped isolate technical performance from contextual factors.

Mogoșoaia recorded a response time of 8.22 s, earning 0 points and indicating a web infrastructure that hampers quick access to information. A middle group (Berceni, Chiajna, Dobroești, Domnești, Glina, Jilava, and Tunari) scored 5 points, with response times ranging from 2.31 to 3.85 s, indicating a modest technical capacity but not critical. In contrast, Clinceni (1.61 s), Cernica (1.68 s), and Vidra (1.83 s) showed high responsiveness and received the maximum score. This variation suggests an indirect relationship between updating frequency and technical performance, with some highly active town halls maintaining good speeds, while others struggle to optimize loading times despite frequent content publishing (

Figure 2).

Desktop optimization, the third sub-indicator, was the only domain where all town halls received full points, indicating convergence around basic technical standards. Across all cases, interfaces showed clear navigation, stable layouts, and no overlapping icons, even on slower or less frequently updated websites. Interestingly, some administrations incorporated advanced animations and visual transitions without compromising platform stability, suggesting an effort to strike a balance between visual appeal and technical reliability.

Mobile optimization showed a sharper divide, with Chiajna as the only town hall that did not earn the maximum score, due to issues such as overlapping icons and broken secondary link navigation. All other sample settlements scored 7.5 points, showing adequate adaptation to mobile environments. Moreover, tests on the Safari browser highlighted Berceni, Dobroești, Domnești, and Glina for offering seamless mobile experiences, with no rendering or interaction errors, reflecting a stronger awareness of the strategic importance of mobile platforms in public communication.

The fifth sub-indicator addressing internal search functionality revealed a clear gap between town halls investing in information accessibility and those without such tools. Cernica, Glina, and Tunari scored 0 points, as the lack of a search function forces users to browse the entire site manually, a slow and discouraging process. The other eight localities scored five points each, allowing for fast and efficient navigation to the desired content. The absence of search features in some cases may signal an administrative orientation focused on information broadcasting rather than facilitating direct access, limiting opportunities for active engagement with the institutional digital environment. Taken together, the institutional web functionality indicator reveals a heterogeneous digital ecosystem, where the formal existence of online platforms coexists with widely varying levels of performance and accessibility. Discrepancies in updating frequency, loading speed, optimization, and navigation tools suggest that digitalization in Bucharest’s peri-urban area does not follow a shared model, but instead reflects individual administrative choices shaped by internal priorities and available resources.

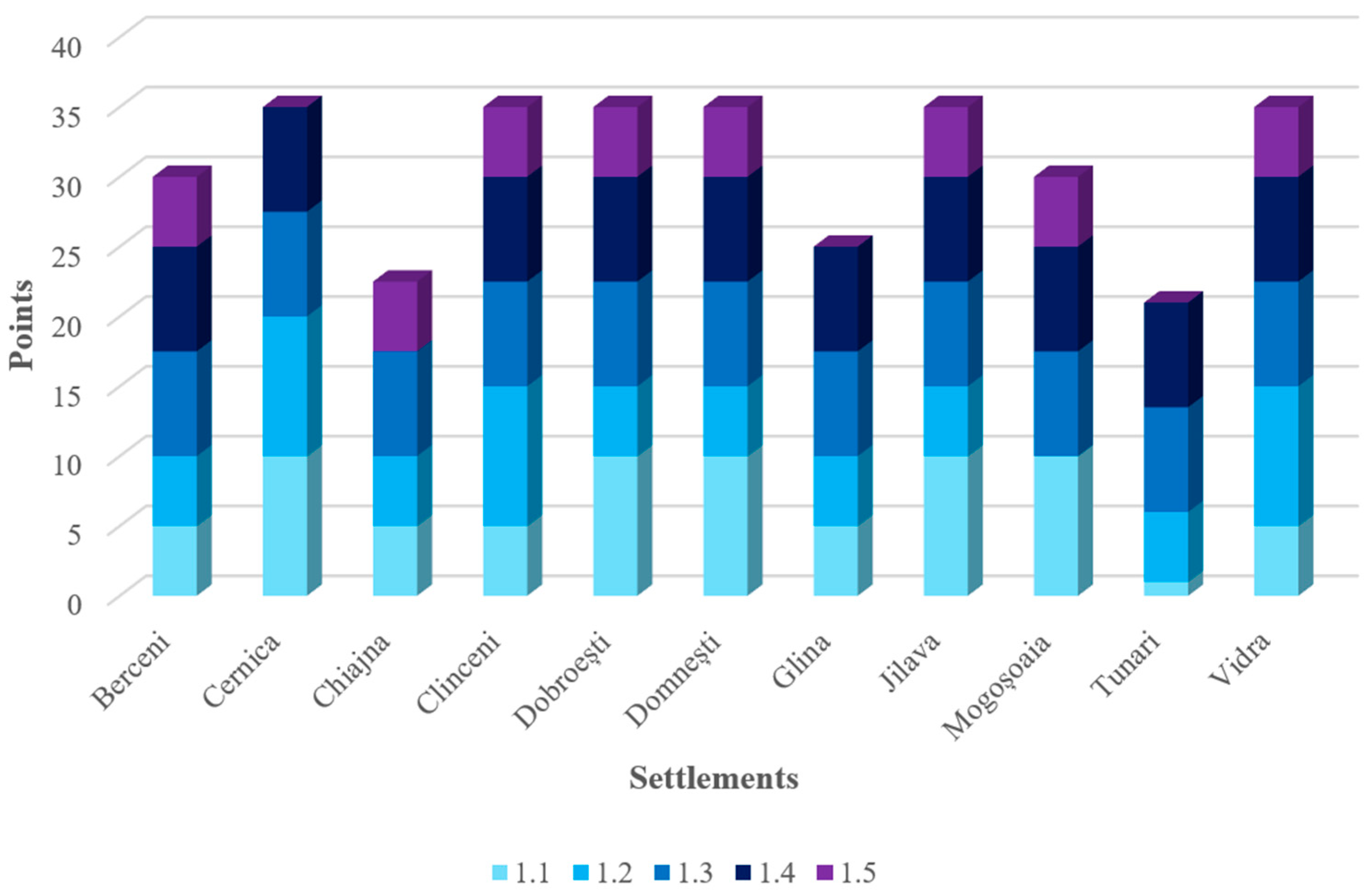

The highest scores for the web functionality criterion (35) are observed in Cernica, Clinceni, Dobroești, Domnești, Jilava, and Vidra, reflecting well-established and functional web infrastructures. The lowest scores are seen in Tunari (21), Chiajna (22.5), Berceni and Mogoșoaia (30) indicating less performant or minimally interactive websites (

Figure 3).

4.2. Digital Public Services

The level of digitalization of public services reflects both the degree of institutional modernization and the capacity to reduce administrative friction in interactions between local authorities and residents.

The availability of online scheduling tools creates a clear line of differentiation among municipalities. While Cernica, Clinceni, Domnești, Glina, and Vidra have no dedicated mechanisms for electronic appointments, meaning that any request still requires physical presence or phone calls, other localities have started building rudimentary forms of digital mediation. Berceni, Dobroești and Tunari indicate that appointments can be requested via email; however, the absence of any explicit mention that this is an officially accepted practice leaves the process ambiguous and dependent on individual employees’ willingness to respond. The approach changes significantly in Chiajna, Jilava, and Mogoșoaia, where automated platforms have been developed to manage requests in a structured way and allocate precise time slots. The contrast between municipalities highlights different technological levels and shows how some local governments have moved toward reducing administrative uncertainty by adopting systems that offer automatic confirmations and transparent scheduling.

The ability to make online payments further amplifies these disparities. In Cernica and Clinceni, there is no digital payment integration, which means that all transactions require physical travel and direct interaction at the counter. An intermediate group formed by Dobroești, Glina, Mogoșoaia, Tunari, and Vidra relies on minimal solutions, where the municipal websites function only as redirecting nodes to national platforms such as Ghișeul.ro. Since there is no real integration, these municipalities cannot track payments in real time and have no direct control over the user interface experienced by citizens. A more advanced level can be seen in Berceni, Chiajna, Domnești, and Jilava, where proprietary systems have been implemented, built through applications such as Plătesconline and Avansis. Technological integration enables instant confirmation of payments and full transaction traceability, significantly reducing processing times and minimizing errors caused by human intermediation.

The availability of standardized online forms introduces another line of separation, more subtle but with consistent administrative implications. All municipalities offer at least some form of digital access to documents, yet the level of sophistication varies. Berceni, Cernica, Chiajna, Clinceni, Domnești, Mogoșoaia, and Vidra rely on static archives of downloadable PDF files that must be filled out offline, which means the submission process remains partly analog and depends on the applicant’s individual initiative. In contrast, Dobroești, Glina, Jilava, and Tunari have adopted interactive systems that allow users to fill out and submit forms directly online, using platforms such as e-confirmare or Avansis. Structuring document flows in digital form brings procedural efficiency and lowers the cognitive barriers associated with traditional bureaucracy by offering a guided, standardized path.

Based on test data for this sub-indicator, three patterns of institutional behavior can be identified. In the first category, the communes of Cernica, Clinceni, Dobroești, Glina, and Jilava (6 points) showed a very high level of responsiveness, providing answers in less than two hours after the request was sent. In the middle range, Domnești (3 points) replied later the same day. Although less prompt, Mogoșoaia and Vidra responded the following day, which still indicates an acceptable level of responsiveness and a functioning public communication system. At the opposite end, the communes of Chiajna and Tunari (0 points) did not provide any reply within 48 h.

A much sharper contrast emerges in the elements of institutional contact, where the visibility and granularity of public information vary drastically. Cernica, Chiajna, Jilava, Mogoșoaia, and Vidra provide only general or informal channels, with no departmental or individual email addresses. In Chiajna, the only visible online presence of the leadership is the mayor’s personal Facebook page, and although an organizational chart is published, it contains no contact information. Jilava and Mogoșoaia only provide a general secretariat address, which creates a rigid intermediary filter between citizens and specific departments. Berceni, Clinceni, Domnești, and Glina represent an intermediate level, offering a few specific departmental addresses. For instance, Clinceni includes contacts for the general secretariat and some adjacent institutions, but not for fiscal or administrative services themselves. The highest level of transparency is evident in Tunari and Dobroești, where every department and nearly every senior official has individual contact details published, including the mayor, deputy mayor, local councilors, and the city manager. This institutional granularity makes digital interaction direct and predictable, considerably reducing the time costs associated with navigating organizational hierarchies. Beyond the scores themselves, their distribution suggests the existence of divergent models of technological integration, where some administrations treat the digital environment as a superficial layer of accessibility without emphasizing restructuring processes, while others have internalized the logic of digitalization and already operate with infrastructures capable of supporting a high degree of automation.

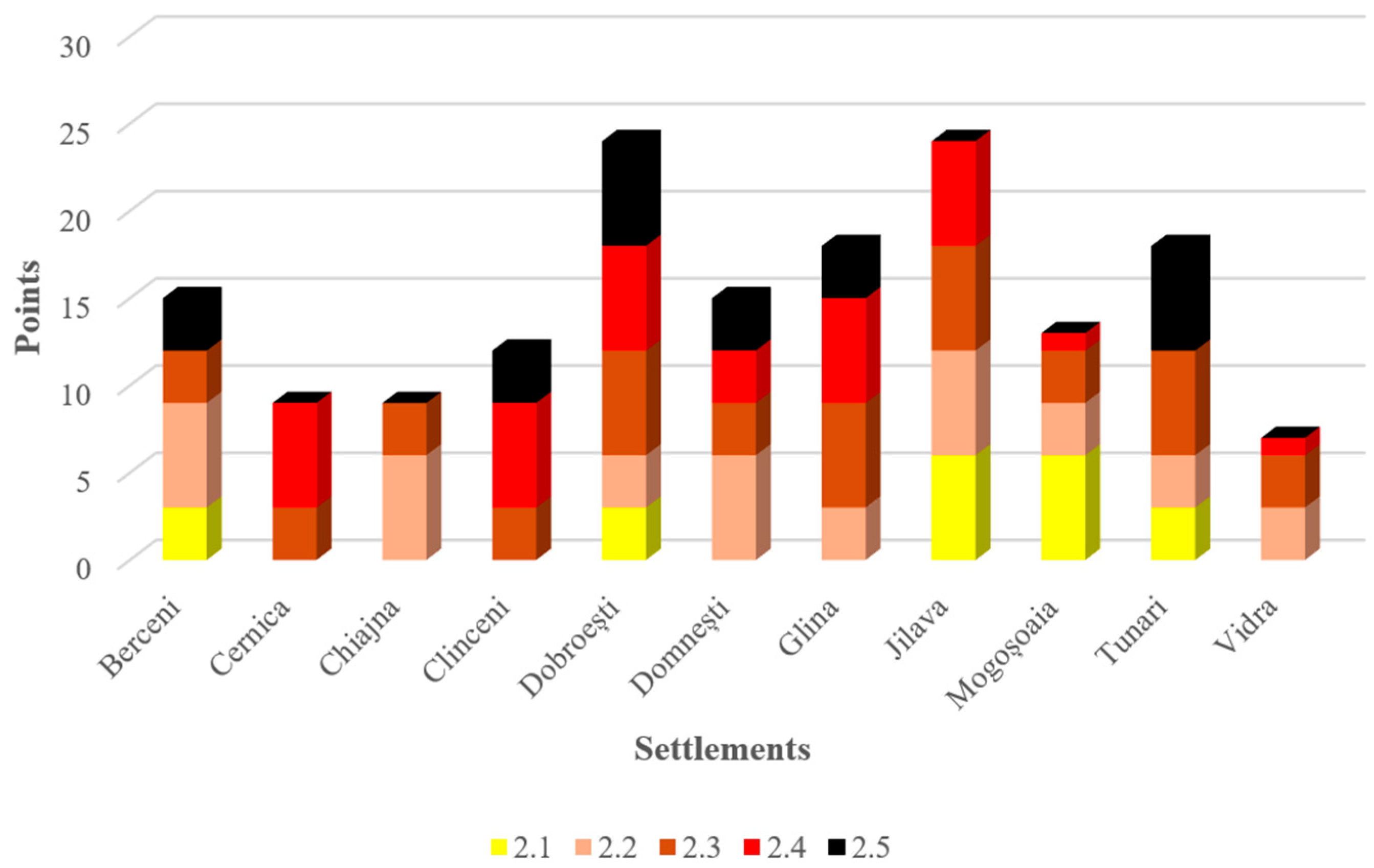

For the second indicator, addressing digital service integration, Dobroești and Jilava (24) are clearly placed in the top leader position displaying online payments, appointment scheduling, and interactive form options on their websites. Vidra (7) and Chiajna (9) display very low levels of digital service integration, highlighting a lack of consistent digital solutions in administrative services (

Figure 4).

4.3. Digital Communication & Information Experience

The level of development of digital tools for information and communication reveals for most local administrations in Ilfov clear delays and fragmented solutions for this digitalization sector.

The complete absence of online feedback questionnaires illustrates the lack of an institutional culture of evaluation from the users’ perspective. None of the eleven localities has implemented such a mechanism, and the isolated attempt by Jilava to introduce an anti-corruption questionnaire failed, as the published link is now inactive. A clearer differentiation emerges regarding online complaint forms or dedicated complaint systems. For this sub-indicator, Chiajna and Dobroești received the maximum score because they have functional mechanisms that allow users to submit complaints directly online. The other nine localities offer no alternative solutions, which keeps a significant part of institutional interactions locked in analog formats. In Clinceni, there is only a downloadable PDF complaint form that must be printed and submitted physically, whereas in Glina, a button labeled as an online complaint system is available, but it does not function and does not redirect the user to any functional online page. The absence of standardized digital channels perpetuates a closed bureaucratic model and reduces the transparency of complaint resolution processes.

The transparency regarding public interest projects marks another area with striking differences in institutional behavior. Mogoșoaia and Tunari do not publish any such projects, and on the Mogoșoaia website, the note that the section is “under update” has been displayed since 2015. Most of other localities, including Cernica, Chiajna, Clinceni, Domnești, Glina, Jilava, and Vidra, publish projects very rarely or leave them outdated for years, which suggests a more symbolic approach than a consistent information practice. In Chiajna, only the local development strategy is available. In Clinceni, there have been no updates since 2022, and in Glina, the last visible update dates to 2021. Only Berceni, Dobroești and Mogoșoaia regularly publish information on ongoing projects, sometimes updating them more frequently than once a month, which indicates a more dynamic and transparent approach.

The availability of digital calendars or announcements about public interest events shows supplementary discrepancies, as only Dobroești and Mogoșoaia have functional dedicated sections that consistently display local council meetings, public consultations, or community events. Elsewhere, practices are inconsistent. Clinceni occasionally posts announcements before meetings, Glina has not updated this section since November 2024, and Jilava displays an empty page labeled as “under update”. In Mogoșoaia, the calendar is well-structured and visible, but it mostly lists past events without clearly indicating upcoming ones. The lack of coherent announcements reduces the visibility of decision-making processes and limits opportunities for public involvement.

Online petition forms are almost entirely missing, which reflects a low level of interest in active civic participation, as Tunari is the only locality that has implemented such a tool for submitting proposals and initiatives related to local development. In Clinceni, there is a subcategory labeled as a petition area, but the page is empty and contains no functional content. Taken together, the results outline a deeply uneven model of digital development, where some administrations have partially integrated modern tools but without coherence between variables, while others treat the online space solely as a passive display board. Only a few rural settlements around Bucharest have begun to develop infrastructures that can support a two-way communication process with residents, while most of them continue to operate within a one-directional paradigm focused exclusively on transmitting information without any effective mechanisms for feedback or public engagement.

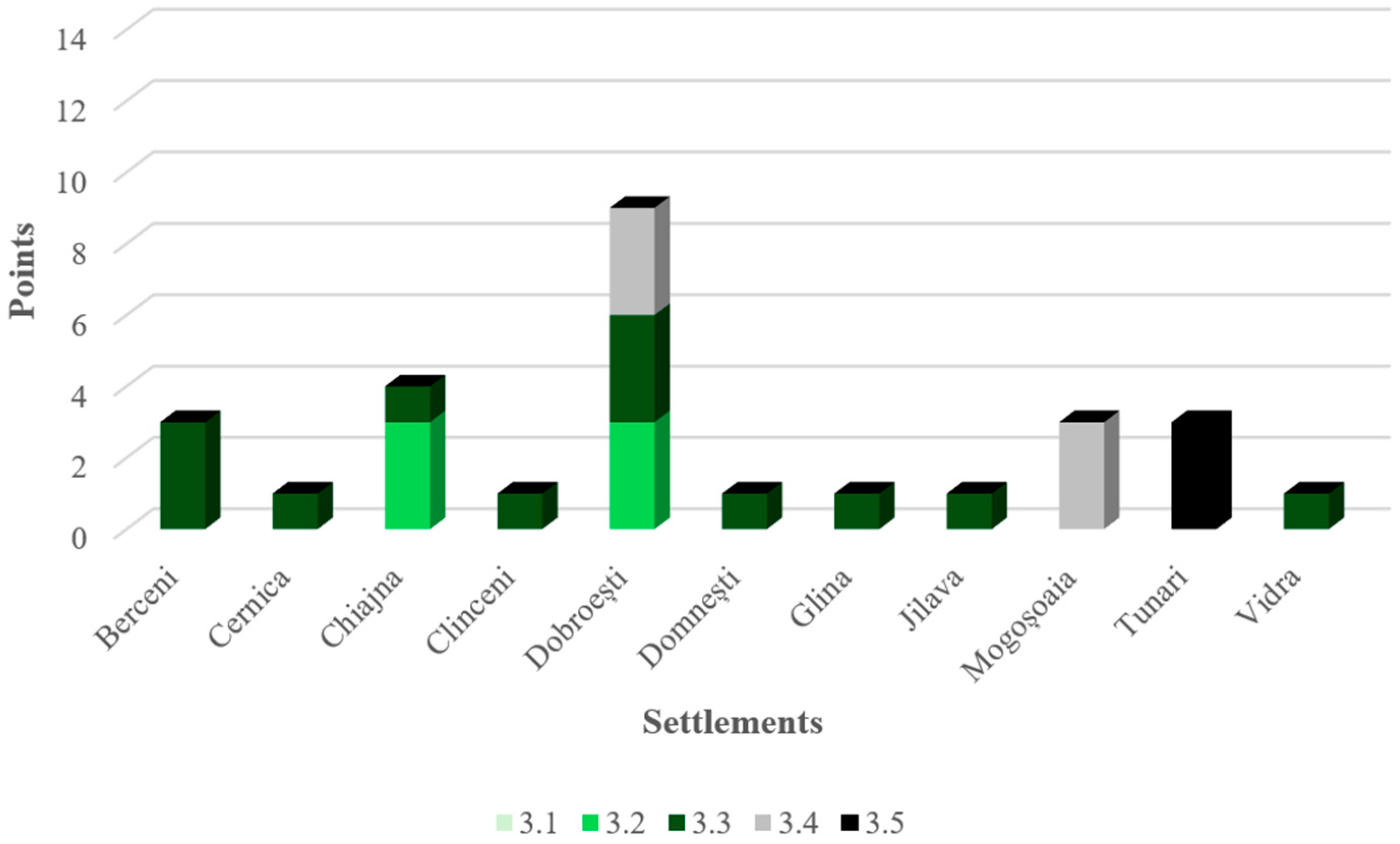

Dobroești stands out with 9 points, and Chiajna scores 4. The remaining localities display scores between 1 and 3, suggesting a weak institutional culture for transparency, user feedback, and bidirectional citizen engagement (

Figure 5).

4.4. Administrative Communication on Social Media Platforms

The presence of local administrations on social media highlights significant differences in how each authority manages digital communication. All eleven municipalities analyzed maintain official Facebook pages, indicating a basic acknowledgment of the role of these channels; however, the frequency of updates varies considerably. Domnești, Glina, Tunari, and Vidra do not update their pages on a frequent basis, therefore limiting through this practice the visibility and relevance of the content. The remaining seven municipalities publish regularly, demonstrating a stronger integration of social platforms into institutional routines.

An

analysis of posts during July 2025 emphasizes the variations in engagement. Domnești, Tunari, and Vidra did not post at all, while Glina posted four times, reflecting a low level of activity. Berceni, Cernica, Chiajna, Clinceni, and Jilava posted between five and ten times, representing a moderate communication effort. Dobroești and Mogoșoaia exceeded ten posts, indicating a proactive and organized approach aimed at maintaining continuous contact with the community. Transparency is limited (

Figure 6).

The publication of council resolutions is fragmented and inconsistent. Clinceni, Domnești, Glina, Jilava, and Tunari do not make these documents publicly available on either their websites or social media pages. Berceni, Cernica, Chiajna, Dobroești, Mogoșoaia, and Vidra partially publish them on their website or social platforms, but updates are infrequent or delayed. Meeting minutes in Chiajna are posted online. Clinceni has not updated since 2022, Glina since 2021, and Jilava since 2023. Tunari lacks a dedicated section entirely. The inconsistency reduces the visibility of the decision-making process and limits residents’ ability to follow council activities.

Differences also appear in the presence of newsletters and official groups. Six municipalities operate channels recognized as official, either by name or through direct involvement of administrative representatives: Berceni, Chiajna, Clinceni, Domnești, Jilava, and Mogoșoaia. The remaining municipalities rely on unofficial groups managed by citizens, which do not allow coordinated or verifiable communication. The absence of official channels restricts the administration’s ability to provide coherent information and respond predictably to community requests. Overall, social media communication remains fragmented and inconsistent. Some administrations have developed official pages into active tools for disseminating information, while others use them sporadically without a clear strategy. The lack of a uniform approach reduces institutional visibility and limits opportunities for civic engagement.

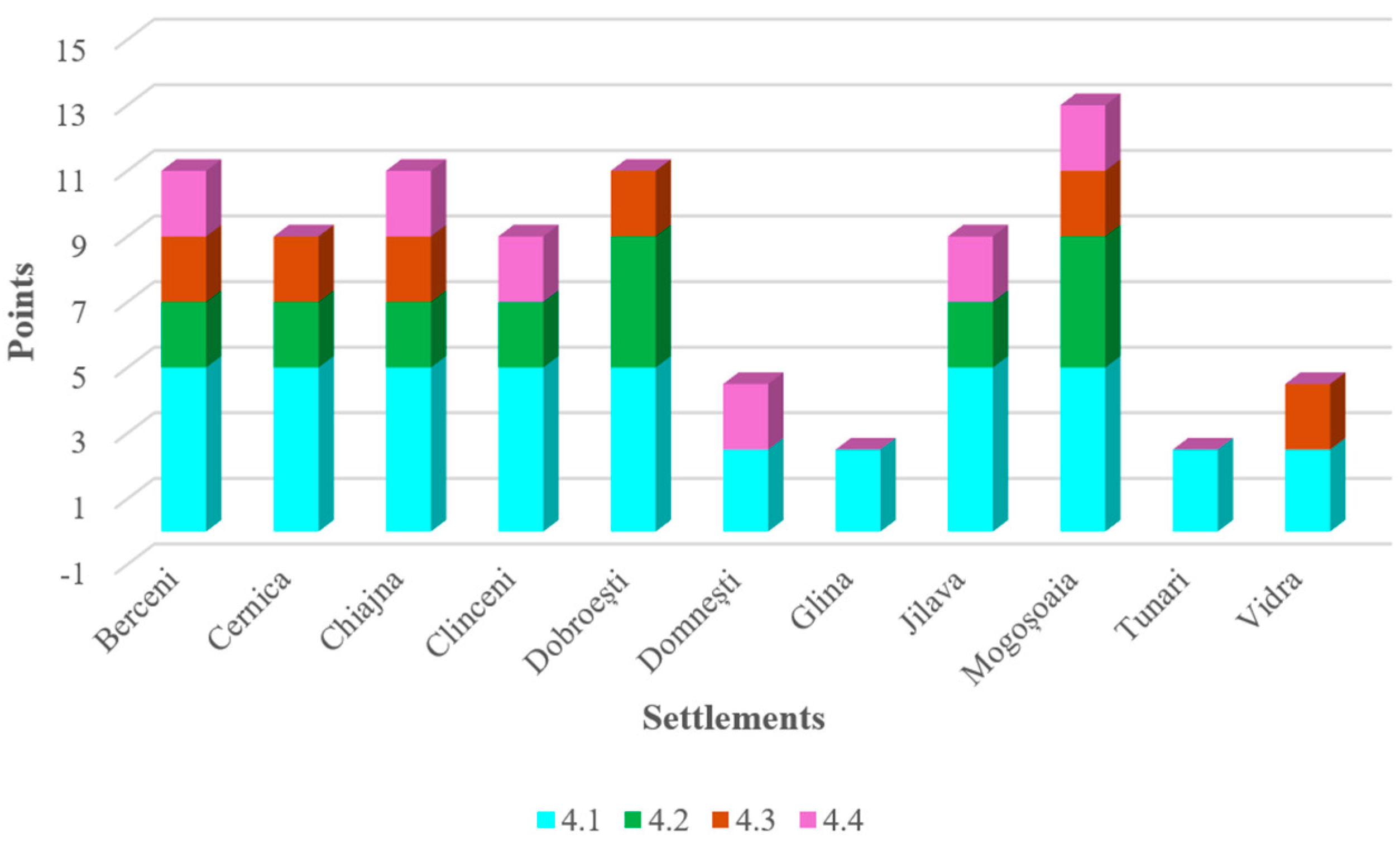

Therefore, for total values on this fourth criterion Mogoșoaia (13), Berceni (11), Dobroești (11) and Cernica (9), actively using social media for public communication, are on top positions. Glina and Tunari (2.5) show marginal use of these platforms. Other communes display moderate scores of 4.5–11, indicating rather sporadic engagement through social channels (

Figure 7).

4.5. Results of the Proposed Digital Maturity Test

The four main variables of the total index addressing the digitalization of administrative services: the institutional website functionality; the existence and/or the performance of digital public services; digital communication and information experience and communication through social media are the main variables which form the backbone of a successful digitalization of administrative services.

Fulfilling all criteria at the highest level should be the goal for administrative authorities aiming to improve their services, thereby enhancing accessibility, reducing response times, increasing transparency, facilitating smoother citizen engagement, fostering greater trust in public institutions, and delivering digital services more efficiently.

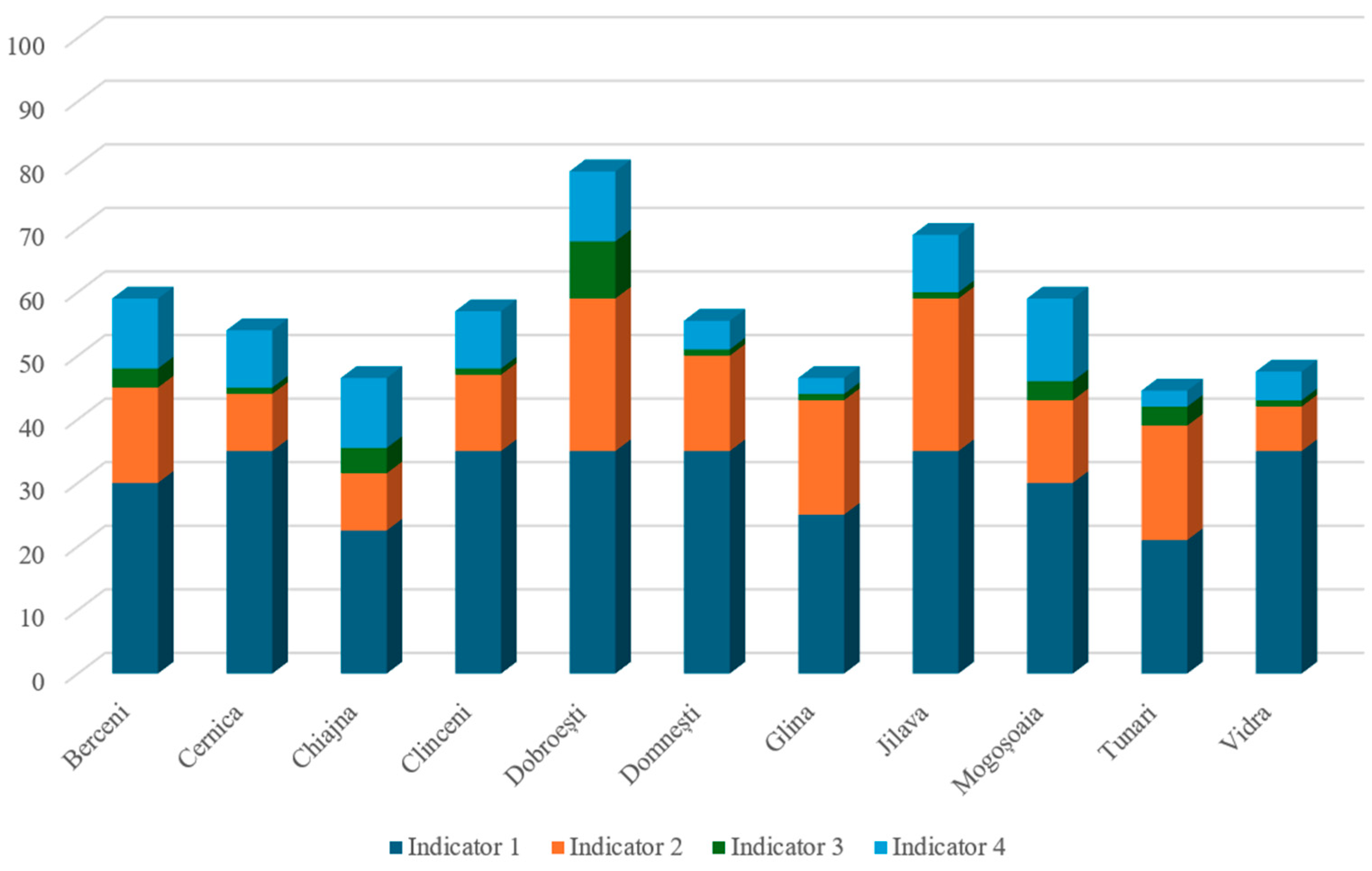

As shown in

Figure 8, when aggregated, the total scores reveal a relatively clear hierarchy. Dobroești (79) and Jilava (69) stand out with stronger integration of digitalization, while Tunari (44.5), Glina (46.5), and Chiajna (46.5) occupy the bottom of the ranking, reflecting a fragmented and largely symbolic approach to digital transformation. The dispersion underscores the absence of a unified development model, where high performance on one dimension (such as web infrastructure) is not consistently matched by equivalent progress in others (services, communication, social media).

The web functionality indicator highlights significant differences among the municipalities studied and reveals how prepared they are to provide real digital access to citizens. Overall, all the localities have functional websites, but not all are regularly updated or fully utilized. Cernica, Chiajna, Clinceni, Dobroești, Domnești, Jilava, and Vidra stand out with a more active online presence. Their sites are consistently updated and optimized for both desktop and mobile devices, allowing residents to find information quickly and efficiently. Dobroești and Domnești are particularly notable for their frequent updates, signaling that these administrations pay continuous attention to their digital presence.

By contrast, Tunari demonstrates that having a website alone is insufficient. While their sites exist and are technically optimized for both desktop and mobile, the lack of frequent updates suggests that their potential remains untapped. In other words, they provide the infrastructure but not the proactive content needed to turn the website into a genuinely useful tool for citizens.

Loading speed is another differentiating factor. Municipalities, such as Chiajna and Glina, could benefit from more optimization. The search function is important for quickly locating information but remains a weak spot for several localities. Cernica, Chiajna, Tunari, and Glina do not offer this feature. This forces users to navigate pages manually. In contrast, Clinceni, Dobroești, Domnești, Jilava, Mogoșoaia, and Vidra provide direct search functionality. This enhances accessibility and efficiency in online interactions.

Taken as a whole, this indicator reveals that digital infrastructure is present almost everywhere, but its quality and functionality vary significantly. Some administrations use their website merely as a static noticeboard, while others, like Dobroești and Clinceni, have turned it into a true tool for communication and access to public services.

The digital public services indicator highlights big differences between administrations in providing efficient online services. Dobroești and Jilava stand out for integrating automated solutions for appointments, payments, and forms. This lets citizens interact quickly with the administration. In contrast, Berceni, Chiajna, Vidra, and Glina have more limited automation. Automated services are largely absent, email replies are often delayed, and direct digital contact with staff is not supported. Tunari falls in between, offering some automation but showing gaps in response times and access to departments. These differences reflect not only technical digitalization but also institutional capacity and administrative culture. Some local authorities invest in digital transformation, while others limit interaction to symbolic elements. The indicator shows that real access to digital public services remains uneven across the region.

The digital communication and information experience indicator reveals a striking lack of consistency across the municipalities, highlighting gaps in citizen engagement and transparency. Most localities score very low, with Cernica, Clinceni, Domnești, Glina, Jilava, and Vidra earning minimal points, indicating the absence of online feedback forms, petitions, and up-to-date project transparency. Dobroești stands out with higher scores, offering a digital calendar, regular updates on projects, and more robust mechanisms for citizen interaction, though it still lacks a feedback form or petition system. Mogoșoaia and Tunari show selective strengths: Mogoșoaia provides a functional event calendar, while Tunari supports online petitions. Overall, the indicator underscores a limited institutional culture around two-way digital communication, where most administrations maintain a largely static presence online rather than fostering meaningful interaction and transparency with citizens.

The social media communication indicator highlights the varying ways in which municipalities engage with citizens through online platforms. Berceni, Cernica, Chiajna, Clinceni, Dobroești, and Jilava maintain official pages, but their activity levels vary significantly. Dobroești and Mogoșoaia stand out with higher post frequencies, showing a proactive approach to keeping residents informed, while others, such as Domnești, Glina, Tunari, and Vidra, maintain pages that are either minimally updated or underutilized. The publication of council decisions is inconsistent: only a few municipalities post them online alongside other platforms, and live-streamed meetings remain absent across all. Official newsletters or social media groups exist in only some areas, further highlighting gaps in structured digital communication. Overall, this indicator reveals that while most localities have the infrastructure to engage citizens via social media, the intensity and effectiveness of that engagement differ widely, with only a handful of administrations using these channels strategically to foster transparency and participation.

The overall results clearly highlight the differences in digitalization among local administrations. The indicators with the highest weight, website functionality (40 points) and digital public services (30 points), largely determined the final scores. Dobroești (79) and Jilava (69) stand out with well-structured websites and efficient automated services, while Tunari (44.5), Chiajna, and Glina (46.5) are at the bottom of the ranking, showing that an online presence without regular updates and functional services remains largely symbolic.

The communication and social media indicators (15 points each) reveal further differences: Berceni, Dobroești and Mogoșoaia actively use these channels for transparency and citizen engagement, whereas others, such as Clinceni, remain passive despite having decent web infrastructure. Overall, the total scores reflect both the level of technical digitalization and the administrations’ capacity to turn digital tools into practical and useful instruments for citizens.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The local administrative landscape in Romania is the result of major transformations within the administration, driven by significant shifts in paradigms and governance models due to regional and global factors.

Societal changes in the post-communist period triggered major political and socio-economic transformations, which were also reflected at the administrative level. The liberalization and decentralization of governance led Romania’s public administration to shift from a centralized and authoritarian model, characterized by discretionary powers over citizens and perceived as a threat (“Leviathan”), to a more open and transparent model, focused on protecting citizens’ rights (

Lazăr, 2012).

The public domain has become more than ever a priority area for reform and a direct interface between residents and administrative authorities. The liberalization of services and democratic interaction with citizens are just two aspects that illustrate this trend (

Ioniță, 2008).

Romania’s membership in the European Union, combined with the global digitalization of services and institutions, which has been strongly accelerated by EU policies promoting digitalization among member states, has led to further major transformations. This has placed significant pressure on administrations at various levels in Romania, including local and county authorities (

Iancu, 2013).

Romania is a country that has undergone significant administrative transformations over the past century witnessing an important urban sprawl over the surrounding areas, particularly emphasized in the case of Bucharest (

Suditu, 2009). The period following 1990, marked by the transition from a centralized communist regime to a democratic system, has seen frequent changes in government and ongoing negotiations of political power among different parties. These dynamics have often led to a lack of consistency and continuity in various measures aimed at enhancing the efficiency of local administration, including its digitalization. Moreover, the extension of the city in the nearby rural territory was often an inconsistent administrative process with statistical background demanding time and public action to increase the maturity of territorial reconfiguration (

Suditu, 2009;

Suditu et al., 2014).

This research aimed to develop an index reflecting the level of administrative digitalization development in Romania, comprising four major key indicators.

The indicator for institutional web functionality (I1) records relatively high values across most municipalities, ranging from 21 in Tunari to 35 in Cernica, Clinceni, Dobroești, Domnești, Jilava, and Vidra. This suggests that basic online presence and infrastructure are largely in place, though the gaps reveal differences in both the pace and quality of implementation.

Based on the data, the first question regarding the presence and quality of institutional web pages, including mobile optimization, is clearly addressed. The I1 scores indicate that most municipalities maintain a functional online infrastructure, with higher scores reflecting sites that are regularly updated and optimized for both desktop and mobile. Lower scores indicate a limited online presence, infrequent updates, and a suboptimal mobile experience, revealing the varying capacities of local administrations to manage and leverage their websites effectively.

For the second research question, the analysis shows that digital public services vary widely across municipalities. Dobroești and Jilava lead with advanced solutions for payments, scheduling, and online forms, while Cernica, Chiajna and Vidra fall behind, highlighting uneven administrative capacity and the lack of a shared regional digital strategy. For municipalities lagging, improvements could include implementing automated payment systems, expanding online appointment scheduling, and providing standardized digital forms to make citizen interactions more efficient and accessible.

The indicator for digital communication and information experience (I3) shows the lowest overall consistency. Except for Dobroești (9) and Chiajna (4), all municipalities score between 1 and 3, underscoring an institutional culture poorly aligned with two-way interaction, project transparency, and feedback mechanisms. This gap indicates that existing digital infrastructures are not supported by equally effective communication processes with citizens.

The contrast between municipalities highlights different technological levels and demonstrates how some local governments have moved toward reducing administrative uncertainty by adopting systems that provide automatic confirmations and transparent scheduling.

Only a few rural settlements around Bucharest have begun to develop infrastructures that can support a two-way communication process with residents, while most continue to operate within a one-directional paradigm focused exclusively on transmitting information without effective mechanisms for feedback or public engagement.

An optimal solution would be the creation of a unified digital platform for local administrations. Such a portal would centralize feedback and complaint submission, provide updated information on ongoing projects, display a comprehensive digital calendar of local events and council meetings, and allow citizens to submit petitions or suggestions directly online. By integrating all these services into a single interface, the platform would streamline interactions, enhance transparency, and foster meaningful citizen engagement.

For the social media communication indicator (I4), the total scores reveal notable differences across the peri-urban municipalities of Bucharest. Mogoșoaia (13), Berceni (11), Chiajna (11), and Dobroești (11) lead the ranking, demonstrating a more active and strategic use of social platforms. Cernica (9), Jilava (9) and Clinceni (9) follow closely, showing moderate engagement, while Domnești (4.5), Vidra (4.5), Glina (2.5), and Tunari (2.5) lag, reflecting limited or symbolic social media activity. These disparities underscore the varying ways municipalities perceive and utilize social media as a tool for communication and citizen engagement.

Active social media presence is a critical dimension of local digital maturity. It enables municipalities to share timely information, increase transparency, mobilize community participation, and foster stronger relationships with citizens. Moreover, it can influence political visibility and reputation, facilitating outreach to interest groups and fostering civic engagement (

Bertot et al., 2010;

Mergel, 2013). Municipalities that neglect these channels risk limiting both their transparency and public interaction.

For municipalities with lower scores, integrated solutions could include creating a unified communication strategy, regularly updating official pages, live-streaming council meetings, publishing council decisions online, and establishing newsletters or social media groups for citizens. Providing dedicated training for administrative staff in content creation and community management can also enhance performance. By adopting these measures, low-performing municipalities can transform social media into a proactive tool for engagement, transparency, and citizen-centered governance.

As an original approach to a topic less explored in the existing scientific literature, the methodological framework proposed in this study outlines a clear and replicable framework for evaluating digital maturity. It provides a solid foundation for extending the study to other localities and for developing more efficient, citizen-oriented digitalization strategies. In addition, the study acknowledges that digital maturity is a multidimensional concept influenced by organizational culture, resource availability, and staff competencies. Previous research has highlighted that successful digitalization is not solely a technical endeavor. It also requires leadership commitment, strategic planning, and continuous training of personnel. While this study primarily focuses on observable digital tools and services, it recognizes that underlying institutional practices and citizen engagement strategies influence the effectiveness of digital initiatives. Future research could explore these organizational and behavioral dimensions to provide a more comprehensive understanding of digital transformation in peri-urban local administrations.

Confronted with time and limited human resources and being at an initial phase of development, this study presents some inherent limitations from the fact that the users and main beneficiaries of digital administrative services were not consulted. Although citizens as beneficiaries of digital administrative services were not involved in the research process, the methodology could be designed to allow future extensions for other stakeholder groups, including various relevant sub-segmentations. These could incorporate user perspectives and experiences, enhance the relevance and applicability of the results and complement the present study with relevant input according to users’ needs and possible adaptations and improvements of the analyzed services.

The study and its current results may already provide valuable input for further recommendations on improved strategic planning in administrative digitalization, offering a structured approach to assessing the current level of digital maturity in peri-urban municipalities around Bucharest. Its methodology is highly transferable, allowing application in other regions to identify gaps, highlight best practices, and guide targeted investments in digital infrastructure, automated services, and citizen communication tools. By providing a clear picture of both strengths and weaknesses, the study supports more efficient, citizen-centered reforms, helping local administrations enhance accessibility, transparency, and overall public engagement.

At the same time, this research also had some inherent limitations that suggest possible completions of the study and future research directions. One limitation includes the type of data which did not include at this stage of research citizens’ input. Unlike many studies that focused on users’ perspectives, our research sought to surpass an objective point of view. In this attempt, we managed to consider, and weigh, based on desk research and also on expert opinions a series of indicators and sub-indicators as components of a synthetical index for administrative services. However, our method is not exhaustive as digital development is very complex and very dynamic, continuously evolving and adding new variables and decreasing or increasing the importance of certain elements within the whole index structure. Another further improvement would be a more complex way of computing variables within the index structure as our study represents for the moment an empirical method and point of view which better corresponds to this exploratory stage of research and could be further extrapolated and exploited through appropriate software solutions.