Food insecurity remains a persistent challenge in conflict-affected regions, undermining livelihoods and socioeconomic development. The following section synthesis the conceptual foundation, theoretical framework, and empirical review of the study, identifies thematic patterns and gaps, and situates the study within scholarly debates on vulnerability and resilience in conflict settings.

2.1. Conceptual Framework

The conceptual framework for this study situates urban household food insecurity within the context of displacement caused by war in Tigray, Ethiopia. Armed conflict is the main driver of disruption because it destroys assets and livelihoods while forcing large numbers of people to move into urban areas (

Araya & Lee, 2024;

Weldegiargis et al., 2023). Displacement creates sharp increases in demand for food, housing, and basic services, placing additional pressure on host communities that were already weakened by the collapse of markets and the loss of income (

Geremedhn & Gebrihet, 2024). Urban households, which rely more on markets and cash income than on self-production, become particularly vulnerable when supply chains fail and food prices rise under the weight of population pressure (

Gebrihet et al., 2025;

Teodosijević, 2003;

Weldegiargis et al., 2023).

Food insecurity, the dependent variable in this framework, refers to the lack of consistent access to safe, adequate, and nutritious food. It is understood across several dimensions: availability, access, utilization, stability, agency, and sustainability (

Banks et al., 2021;

Su & Amrit, 2024). Urban host households are highly exposed because they depend on wages, remittances, or small-scale trade to secure food. When displaced populations arrive, competition for jobs increases, wages decline, and living costs rise, reducing households’ purchasing power. At the same time, disruptions to trade routes and supply chains restrict the availability of food, creating price increases and market instability. Together, these pressures reduce households’ ability to maintain adequate and stable consumption, producing both immediate and longer-term food insecurity.

Urban host households respond to these pressures by adopting a range of coping strategies. Some reduce meal frequency and dietary diversity, while others borrow food or money, rely on humanitarian aid, engage in informal work, or share resources within extended family and community networks. These responses provide short-term relief, but their effectiveness diminishes when displacement persists, and humanitarian needs remain widespread. As both displaced and host populations depend on the same limited urban resources, coping mechanisms quickly become overstretched, leaving many households in chronic or recurring food insecurity.

In this framework, displacement caused by war is the central independent variable. It undermines urban food security both directly and indirectly by increasing demand, straining markets, and weakening household entitlements. Food insecurity, the dependent variable, will be analyzed across the dimensions of availability, access, affordability, and stability. The framework therefore emphasizes how displacement reshapes urban vulnerabilities and influences the resilience of host households as they attempt to maintain access to adequate and nutritious food during prolonged conflict.

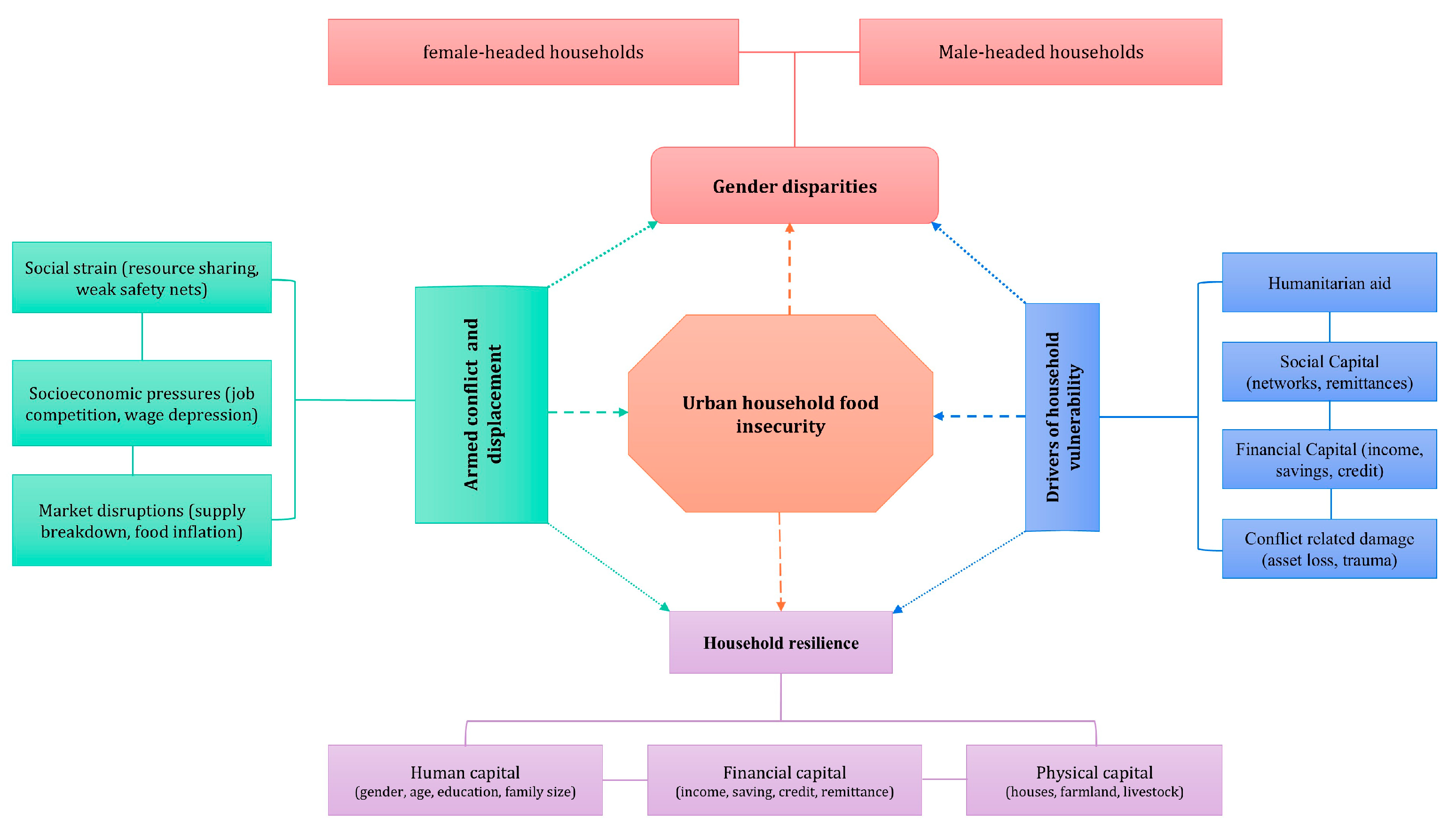

Figure 1 presents the causal pathways linking armed conflict, displacement, and urban household food insecurity in Tigray, Ethiopia.

Armed conflict triggers mass displacement, which exerts economic, social, and institutional pressures on urban host households. These mediating factors, such as income loss, market disruption, gendered vulnerabilities, and asset depletion, increase the likelihood of food insecurity across multiple dimensions (availability, access, affordability, and stability). Humanitarian assistance and social capital can partially mitigate these effects, though their influence weakens under protracted siege conditions. The framework emphasizes the dynamic interactions between conflict, displacement, and household resilience in shaping urban vulnerability.

2.2. Theoretical Framework

Household vulnerability frameworks conceptualize food insecurity as a function of exposure to shocks, sensitivity of livelihoods, and adaptive capacity (

Ellis, 2000;

Moser, 1998). In the context of war-induced displacement, urban host households face shocks not from agricultural collapse but from sudden increases in population pressure, market disruption, unemployment, and rising living costs. Their sensitivity stems from their heavy dependence on market-based food access, with limited buffer mechanisms such as savings or social protection. Adaptive capacity is further constrained, as community support systems, humanitarian assistance, and informal safety nets are stretched thin by the simultaneous needs of both displaced and host populations.

Sen’s Entitlement Theory remains particularly relevant in explaining food insecurity under urban displacement (

Sen, 1983). In Tigray’s urban centres, these entitlements have been severely disrupted: local labour markets collapsed, small businesses closed, and remittance flows were interrupted. Blockades and restrictions on humanitarian aid further limit entitlement (

Clark, 2021). Displacement magnifies these pressures by intensifying competition for jobs and services, thereby reducing host households’ capacity to convert entitlements to food security (

Gebrihet & Gebresilassie, 2025b;

Geremedhn & Gebrihet, 2024). While Entitlement Theory explains access-based vulnerabilities,

Devereux (

2001) critiques them for underplaying political dynamics. In war-affected contexts, such as Tigray, state actions, aid restrictions, and broader governance failures can amplify household vulnerability, creating structural barriers to securing food.

The Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (

DFID, 2008) provides a holistic lens by linking food security to households’ access to, and use of, diverse livelihood assets. In the urban host communities of Tigray, displacement has eroded multiple forms of capital: financial capital is weakened by unemployment and inflation; social capital is strained as hosts share resources with displaced families; physical capital, including housing, markets, and water systems, is overstretched; and political capital is undermined by governance failures and restrictions on aid (

Natarajan et al., 2022). The SLF, when adapted to displacement contexts, illustrates how conflict reshapes the urban asset base and constrains households’ abilities to cope and adapt.

The human security theory posits that food security is integral to overall well-being, emphasizing how conflict simultaneously threatens physical, economic, and social survival (

Fouinat, 2004;

Jolly & Ray, 2006). Political economy perspectives complement this view by demonstrating how war and displacement reconfigure power relations in urban spaces, privileging households with access to humanitarian aid or remittances while marginalizing poorer host families. Structural barriers, such as disrupted markets, high food prices, and limited employment opportunities, further exacerbate inequality in food access (

Geremedhn & Gebrihet, 2024;

Israni, 2024).

Resilience theory adds insight by examining how households adapt to displacement pressure (

Folke et al., 2010;

Shilomboleni et al., 2024). In Tigray’s host communities, coping strategies include reliance on food aid, engagement in informal employment, borrowing, and dietary adjustments (

Eshetu et al., 2025;

Gebrihet & Gebresilassie, 2025a). However, resilience is uneven: households with diversified incomes, stronger networks, or external support adapt more effectively, while poorer households quickly exhaust their coping mechanisms. Prolonged displacement and conflict undermine recovery pathways, resulting in chronic food insecurity for large segments of urban populations.

These theoretical perspectives provide a comprehensive lens for understanding urban food insecurity in war-affected Tigray. They illustrate how armed conflict and displacement disrupt entitlements, strain urban assets, and limit adaptive capacity while also highlighting the mechanisms through which host households attempt to cope and build resilience. By integrating entitlement theory, livelihood approaches, human security perspectives, and resilience thinking, this study situates empirical investigation within a robust conceptual and theoretical foundation. This enables a nuanced understanding of how conflict-driven displacement interacts with structural, economic, and social factors to shape urban host communities’ vulnerability to food insecurity.

2.3. Empirical Review

Empirical studies highlight that food insecurity in conflict settings emerges from multiple determinants including socioeconomic status, education, gender, and social capital (

d’Errico et al., 2023;

Giannini et al., 2021;

Sileshi et al., 2019;

Gebrihet & Gebresilassie, 2025c). In urban contexts, displacement adds a critical layer to these vulnerabilities by increasing the demand for food, housing, and services, thereby driving up prices and intensifying competition for scarce jobs (

Büscher, 2018;

Jacobs & Kyamusugulwa, 2018). Host households with limited incomes or weak social networks are particularly disadvantaged as they must navigate market disruptions while accommodating displaced populations. This dynamic reflects findings from South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Yemen, where urban host communities face rising food insecurity following large inflows of displaced people (

FAO, 2024;

Hashim et al., 2021;

Ibrahim et al., 2024).

Socioeconomic status, education, asset ownership, and livelihood diversification strengthen household resilience. d’Errico et al. (2023) found that households with diversified incomes and higher education levels exhibit a greater capacity to withstand shocks across 35 countries.

Giannini et al. (

2021) showed that livelihood diversification reduces climate-related vulnerability in Senegal. Gendered dynamics remain central to the understanding of household vulnerability (

Gebrihet & Gebresilassie, 2025c). Similarly to rural settings, women-headed households in urban Tigray face disproportionately higher risks of food insecurity due to limited access to stable employment, credit, and social protection (

Gebrihet & Gebresilassie, 2025b). Displacement compounds these challenges, as women in host communities often assume caregiving responsibilities for displaced relatives while managing fragile household food budgets (

Geremedhn & Gebrihet, 2024). Studies from Syria and Yemen have also demonstrated how displacement reshapes gendered vulnerabilities, placing additional burdens on women to secure food and income under conditions of scarcity and disrupted services (

Hashim et al., 2021;

Ibrahim et al., 2024).

Urban households in host communities are highly exposed to food insecurity because of their dependence on markets rather than on self-production. In Tigray, disrupted trade routes and repeated blockades destabilized food supply chains, while displacement-driven population growth intensified demand, leading to sharp price increases and reduced affordability (

Eshetu et al., 2025;

Weldegiargis et al., 2023). Evidence from Shire and Mekelle illustrates that host households experienced declining purchasing power, even when food was available, as competition with displaced populations depressed wages and inflated the costs of living. Similar outcomes were observed in urban centres in South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo, where displacement magnified market instability and eroded household-coping capacity (

Büscher, 2018;

Jacobs & Kyamusugulwa, 2018).

Coping strategies adopted by urban host households mirror broader patterns documented in conflict literature but are shaped by the unique pressures of displacement. In Tigray, these include reducing meal frequency and dietary diversity, borrowing money or food, relying on humanitarian assistance, and engaging in informal or precarious employment (

Eshetu et al., 2025;

Gebrihet & Gebresilassie, 2025a). However, as displaced and host households draw on the same overstretched resources, their coping mechanisms quickly weaken, leading to chronic food insecurity. Comparative studies from Yemen, Syria, and South Sudan confirm that prolonged displacement undermines host community resilience by exhausting both social support networks and humanitarian response capacity (

FAO, 2024;

Kafando & Sakurai, 2024;

WFP, 2023).

Within Ethiopia, urban households are already vulnerable to food insecurity because of reliance on markets, inflation, and limited social protection (

Gebresilassie & Nyatanga, 2023). Rural households depend on markets, face limited financial services, and confront environmental stressors such as locust infestations (

Gebrihet & Gebresilassie, 2025a,

2025b). Structural vulnerabilities increase exposure when shocks disrupt supply chains, transport, or income-generating activities (

Araya & Lee, 2024;

Gebrihet et al., 2025). Social safety nets, income diversification, and livelihood interventions support resilience. Evidence from other regions of Ethiopia demonstrates that cash transfers, community support systems, and technological innovations reduce both chronic and shock-induced vulnerability (

Sileshi et al., 2019).

Tigray illustrated the compounding effects of conflict on household food insecurity. Prior to 2020, most areas were food secure (IPC Phase 1) or stressed (Phase 2) owing to soil rehabilitation, irrigation, and safety net programs (

Clark, 2021). The conflict between 2020 and 2023 disrupted agricultural production, destroyed infrastructure, depleted livestock, and restricted market access. Rural households face 77% food insecurity, while urban households experience 39% vulnerability, with female-headed households disproportionately affected (

Araya & Lee, 2024;

Gebrihet et al., 2025).

Dependence on rural agricultural production amplifies conflict-induced urban food insecurity.

Eshetu et al. (

2025) report that urban households rely on external markets, reducing immediate exposure, but maintaining vulnerability through disrupted supply chains. Conflict eroded traditional coping mechanisms such as social networks, savings, and community support. Evidence from Burkina Faso, South Sudan, Syria, Yemen, and Nigeria reinforces rural vulnerability to agricultural destruction, market disruption, and asset loss (

FAO, 2024;

George et al., 2021;

Hashim et al., 2021;

Kafando & Sakurai, 2024;

WFP, 2023).

Despite extensive research on the relationship between conflict and food insecurity, important gaps remain. Most studies focus on national aggregates and overlook the specific vulnerabilities of urban host communities that accommodate displaced populations. Few investigations examine how displacement pressures, combined with asset destruction and livelihood disruption, shape food insecurity at the household level. Evidence from Tigray, which experienced one of the most acute sieges and humanitarian blockades in Africa, is particularly limited.

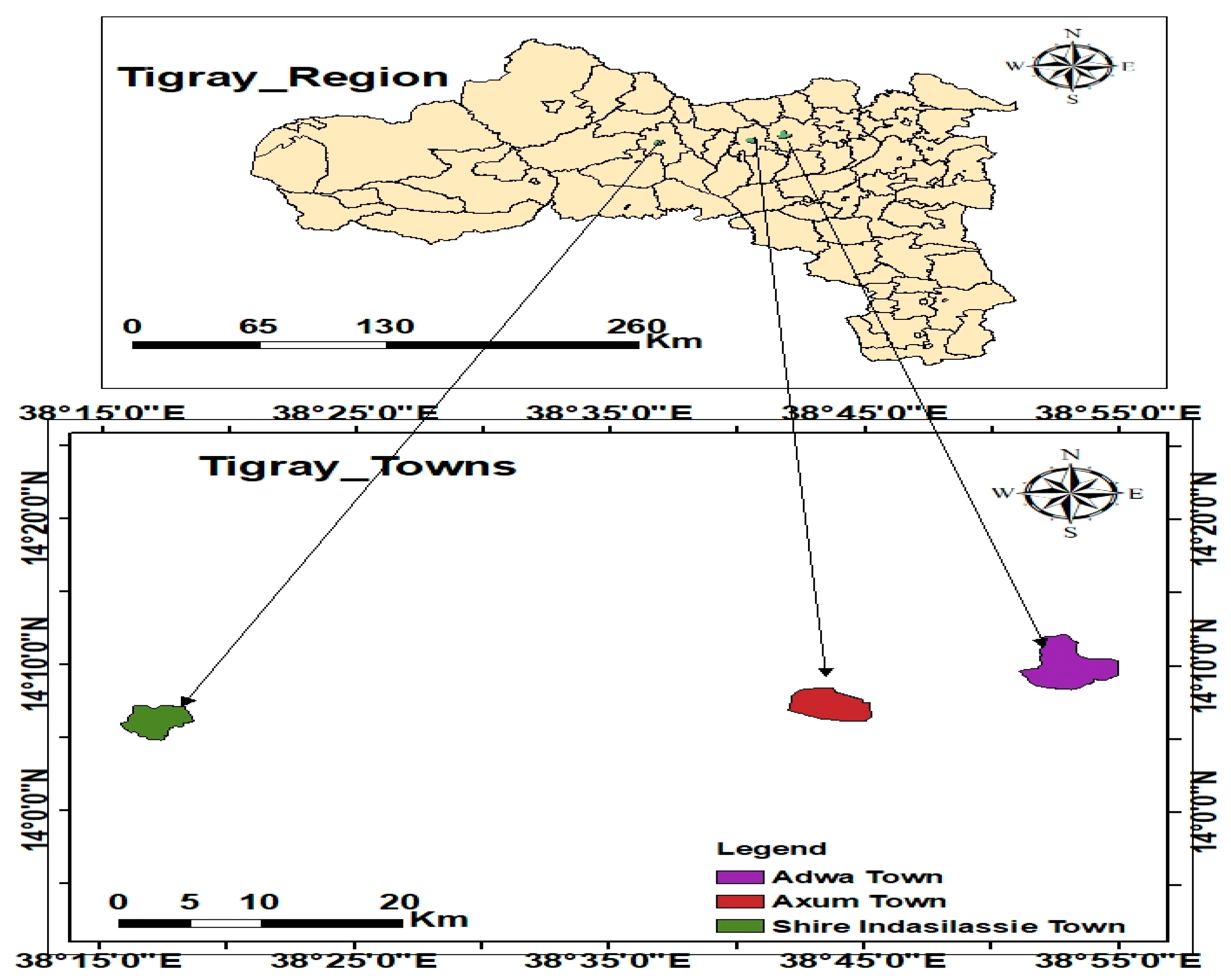

The Tigray case also presents a distinct pattern of displacement and urban food insecurity. Initially, urban residents moved to rural areas as conflict intensified in cities. Later, as fighting spread to rural areas, urban centres such as Shire, Adwa, and Axum became hosts to large numbers of displaced rural households. These urban populations were already struggling with livelihood losses and reliance on unstable markets. The regional siege and communication blackout worsened conditions by severing supply chains, halting remittances, and limiting humanitarian access. This combination of multi-directional displacement, market collapse, and isolation created a complex environment that intensified household food insecurity.

This study addresses these gaps by examining urban household vulnerability to food insecurity in post-war Tigray. Studying Tigray therefore contributes to a deeper understanding of the urban dimensions of vulnerability in protracted conflicts and highlights the importance of context-specific approaches in addressing food insecurity. The use of the Household Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES) and ordered logit regression provides a rigorous way to quantify household vulnerability and identify structural and displacement-related determinants.