Abstract

It is reasonable to state that gastronomic tourism is an efficient tool that has the potential to refresh Thailand’s macroeconomic viability. With the aim of becoming a hub of tourism in Southeast Asia, Thailand’s tourism industry must urgently address and sustainably integrate gastronomic activities to navigate the troubled situation caused by its decline after the COVID-19 pandemic. This has led the authors to conduct a deep study on a regional input–output (I-O) table analysis for Thailand’s tourism system, specifically focusing on gastronomic activities and tourism industries. The tourism I-O data used in this study come from the official source provided by the Thailand Ministry of Tourism and Sport. Empirically, the results of the dynamic regional I-O model predict that Bangkok and its surrounding areas are the heart of gastronomic tourism development, driving income into Thailand’s economy. The eastern region stands as the second-largest area of gastronomy tourism, generating a positive impact on Thailand’s economy. On the other hand, the Northeast of Thailand receives less income from gastronomy tourism despite being the largest area in the country. Ultimately, there should be a greater emphasis on gastronomy tourism policies in order to fully maximize their potential for tourism development, stimulating every part of Thailand during the economic depression caused by COVID-19. Moreover, gastronomy tourism has the potential to play an important role in driving economic growth through the combination of cuisine and tourism development.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, gastronomy generates significant income for the global tourism industry by offering cultural experiences and influencing travelers to engage in food tourism. According to market research, the global gastronomy tourism market was valued at USD 237.7 billion in 2020 and is predicted to grow at an average rate of 14.2% per year from 2021 to 2028. For the Thai economy, gastronomy tourism may be a potential key factor in driving the tourism industry of Thailand after its decline caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

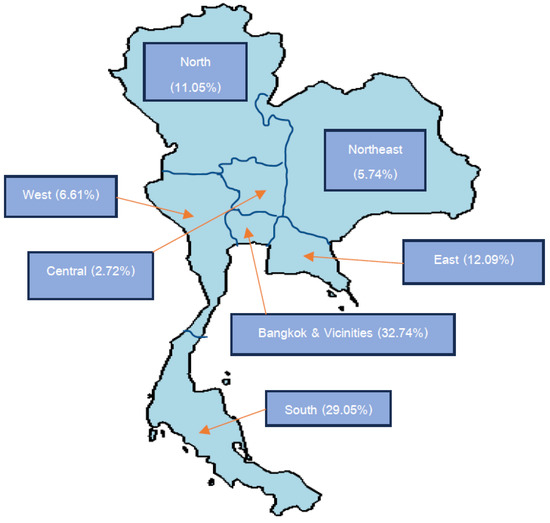

The policy of promoting high volumes of inbound tourists has produced good results in tourism revenues for Thailand’s economy for several decades (Chaitip and Chaiboonsri 2009; TAT 2019). However, most of the tourism income, especially spending on gastronomic activities in 2020, is generated by centralized travel in capital cities (Thailand Ministry of Tourism and Sports 2019) (see Figure 1). Figure 1 confirms the abnormal distribution of travel styles (spending on gastronomic activities) in Thailand’s regional areas. Bangkok and its surrounding areas are commonly regarded as the center of Thailand’s tourist destinations, accounting for approximately 32.7% of tourist arrivals for gastronomy spending. However, the problem lies in monitoring regional distributions. The Northeastern region is the largest region in Thailand, but it only accounts for 5.74% of inbound tourist spending on gastronomy activities.

Figure 1.

The distribution of travel styles, especially gastronomy tourism spending, in Thailand. Source: Thailand Ministry of Tourism and Sports (2019).

On the other hand, the Southern region, despite having a smaller area, attracts 29.05% of tourists who choose to travel and spend on gastronomy activities in Thailand. There is also an imbalance in travel styles for gastronomy activity between the Western and Eastern regions (Thailand Ministry of Tourism and Sports 2019). Additionally, the Central region, which is the area connected to the capital city, surprisingly attracts the minimum number of tourists for gastronomy spending. Consequently, this information reveals the problem of tourism management, especially in the context of gastronomy tourism development, in many parts of Thailand. Therefore, achieving balanced economic development for every part of Thailand based on the gastronomy tourism industry should be a crucial topic for long-term prosperity without harming the environment (United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)1).

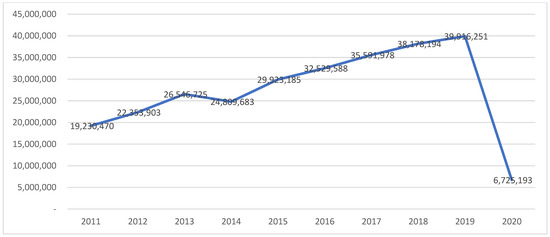

Besides inefficient management for promoting rural tourism in Thailand causing the country to miss a chance to become the central tourism destination in Southeast Asia, Thailand tourism was collapsed by the COVID-19 pandemic that started in the fourth quarter in 2019. Figure 2 shows the dramatic fall in tourism arrivals during 2019 and 2020. This shock immediately shut down international and domestic tourism activities and caused small businesses to continuously decline due to declining tourism markets. However, rural tourism and agricultural activities can play a key role in refreshing the market. It is recommended that gastronomy tourism (also commonly referred to “food tourism” or “culinary tourism”) be politically reconsidered. Gastronomy tourism has currently become a major force in travel and local development (Kiráľová and Hamarneh 2017; Rachão et al. 2019; Rinaldi 2017). Thailand has gained advantages because of its highly logistically favorable location. Additionally, every single area in the country has a significant level of cultural uniqueness, including unique local foods and stories.

Figure 2.

The number of tourist arrivals (person) in Thailand from 2016 to 2020.

In other words, consumers travel for food and try to seek experiences that drive the destination choices of people worldwide. Interestingly, many checking points have made highlighting food and drink offerings as a key part of their messaging strategy. Ultimately, gastronomy tourism is the ideal way to connect agricultural employment with small businesses (SMEs) in the upcoming future, thus helping to promote sustainable development according to the 2030 SDGs (Goal#2) of the United Nations (2020), sustainable food and agriculture by FAO (2020), and creative economy by UNESCO (2013).

2. The Review of Tourism Management and Reginal Input–Output Analysis

The positive consequences of efficient tourism management—job creation, the expansion of investments, infrastructure development, and improvements in standard of well-being—have been found in many host areas (Brankov et al. 2019; Liu and Var 1986; Mitchell and Reid 2001). However, all tourism development has to face trade-offs between what investors consider to be benefits and the costs of those benefits. In terms of the situation in this article, investors are government authorities who are curious about people’s votes. Hence, substantial policy implementations are the key motivation for regional input–output (I-O) analyses. A regional I-O model permits a deep investigation of certain problems in a space economy, referring to changing regional and interregional structures based on a set of restrictive assumptions (Isard 1951). For the historical research review, regional I-O analysis is broadly used to macroeconomically monitor crucial sectors; for example, Rey (2000) started to integrate regional econometric tools which arise from multiregional linkages and spatial effects and I-O modeling simultaneously. Santos (2005) studied regional decomposition in the I-O table for capacitating a more focused and therefore a more accurate analysis of interdependencies for regions of interest in the 1997 US Economy. Zhang et al. (2016) applied a multi-regional I-O analysis to compute economic impacts in a Chinese industry which intends to withdraw demand-driven water. Hardadi and Pizzol (2017) employed multiregional I-O analysis to incorporate the environmental dimension and the social dimension in extending the theoretical framework, thus enabling advancement in the use of social life cycle assessment. The characterization of labor-related impacts was the main issue in highlighting unemployment impacts on human productivity in the United States.

Stadler et al. (2018) applied multiregional I-O to environmentally extend a comprehensive description of the global economy and analyzed its effects on the environment. They gathered data from the EE MRIO databases which range from 1995 to 2011 for 44 countries, thus five regions of the world. An important conclusion of the paper was that the high sectorial detail and wide spectrum of the I-O data allow for both economy-wide assessments and the identification of environmental hotspots (i.e., energy production, food, and mobility). In contrast to I-O data for macroeconomic research, it is rare for tourism sectorial analysis to be empirically focused. Because of the difficulties of official data collection and accessibility, the huge gaps in research are the impetus to create official tourism I-O tables to describe multipliers of tourism activities and affiliated industrial sectors. Zimmermann et al. (2013) were among the few tourism I-O researchers, and they conducted research in Mecklenburg–Western Pomerania, Germany. This paper combined regional tourism economic structures and I-O analyses to quantify output, value-added, and wage bills referring to tourists’ demands when coming to the German state. As an inspiration, the current paper applied the idea of dynamic regional I-O analysis for monitoring ‘Gastronomy’ tourism sectors affecting Thailand’s economic viability, based on the initial assumption that the COVID-19 pandemic can be efficiently controllable in Thailand.

3. The Dynamic I-O Model for Regional Analysis of Thailand

The dynamic I-O model has been applied to analysis in the tourism industry context beginning with Dwyer et al. (2010), who explained how to use this model to evaluate the impact of tourism policy in the world tourism sector. Moreover, in 2013, Zimmermann and Hirschfeld utilized this model to analyze the impact of climate change on tourism development in Mecklenburg–Western Pomerania, Germany. The dynamic I-O model continues to work very well. Kronenberg et al. (2018) utilized the dynamic I-O model to evaluate tourism’s economic contribution in a regional context for Sweden. However, in the gastronomy tourism sector, there are still only a few research articles that have applied this model to evaluate its economic impact, especially the impact of tourism on the economy based on the context of regional gastronomic economic impact. Therefore, this research article would like to utilize the dynamic I-O model to examine the economic impact of gastronomy tourism in several areas in Thailand.

For the beginning of the methodological section, the condition is to start with a concept of single-region analysis. The research scope focuses on Thailand’s tourism sector, specifically considering gastronomic activities. Inside the country, we, therefore, proceed to a model that attempts to capture not just intra-regional interactions but also interregional linkages. The fundamental aim of single-region I-O models is to measure the impact on regional output of changes in regional final demand. National output and final demand are demonstrated as the following vectors:

To address the economy as a whole, inside the equation , the matrix A can be defined as the classification of national commodities:

It is necessary to extensively modify the matrix (A) for a regional analysis of Thailand; the process followed here is below.

where

= the proportion of output for the production sector (i) in a specified region (R). Seven regions of Thailand are compared with the total output of the same production sector (i) of the whole of Thailand:

= the total output of the production sector (i) in a specified region (R) of Thailand

= the export output of the production sector (i) in the specified region (R) of Thailand

= the import output of the production sector (i) in the specified region (R) of Thailand

In the regional case, the matrix A of the I-O model which would be applied in the regional analysis of Thailand needs to be modified by multiplying it by (Equation (1)).

Then,

To modify the previous composed vectors X and Y, the formation of the model can be demonstrated as follows (Miller and Blair 2009; Sargento 2009): (see Equation (2))

This equation quantifies the nationwide effect on the total output for each product category, driven by an exogeneous change in the demand of either one or more national sectors’ and/or one or more regional sectors’ outputs. Moreover, the formula of the Dynamic I-O model for a regional analysis of Thailand must be transformed again (see Equations (3) and (4)).

where

= the identity matrix

= the capital coefficient matrix of a specified region of Thailand

= the output of a specified region of Thailand

= the final demand of a specified region of Thailand

When T = 3, i.e., three years, ()

This calculation technique has been implemented in this research article for the four linear equations already mentioned above, in which it was necessary to delete Equation (8). Therefore, the overall input/output results of the estimation by the Dynamic I-O model for the regional analysis of Thailand are stated in Equations (9)–(11).

From Equations (9) and (10), it can be explained that , , and are the output of the Dynamic I-O model for the regional analysis of Thailand in one year each. However, this research article only focuses on a one-year prediction (2021) based on gastronomic tourism’s economic impact on the regional economy of Thailand. The significant multiplier measurement for the Dynamic I-O model can thus be computed by .

4. Data Review

4.1. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Thailand Gastronomic Tourism

At the moment of writing, Thailand has efficiently controlled the COVID-19 pandemic since the detection of the outbreak in 2019. With confidence underlying a strong public health system and the country’s prior experiences with major breakouts, the number of infections is impressively low (World Health Organization 2020). However, strict control has inevitably caused a depression in the country’s economy. International tourism is the most harmed sector. Hence, domestic purchasing power is intensively considered. Gastronomic tourism is an activity directly connected with domestic consumption. Table 1 details information that supports this idea. In 2020, almost 736,052 million Baht was contributed to the economy of Thailand by domestic gastronomic spending. Bangkok (the capital city) together with the vicinities and provinces of the Southern region were the leading gastronomy destinations, gaining record gastronomy spending of 240,984 and 213,820 million Baht, respectively. The Northern and Eastern regions were comparatively minor gastronomy tourism destinations. The Northeastern region, the largest area in Thailand, generated a similar income via gastronomy tourism to the Western region, which is one of the smallest areas in the country. Lastly, the Central region was the only area in which gastronomy tourism was not the major source of income.

Table 1.

The situation of gastronomy tourism in Thailand during 2020 and initial predictive Beta for the dynamic I-O model.

Another important detail represented in Table 1 is the initial predictive Beta for a dynamic I-O computation. Based on an optimistic foresight for 2021 GDP growth because of the efficient control of COVID-19 outbreaks, 5% is the initial rate used to set the portions of regional outputs. This therefore confirms that Thailand is facing an unsustainable level of development in gastronomy tourism because the tourism destinations are intensively concentrated in Bangkok and the Southern region. These areas have been reported to be at risk of causing outbreaks of the virus since December 2020. New cases observed in a shrimp market in Samut Sakhon province near Bangkok are migrant workers from neighboring countries. Additionally, seafood from the province is widely delivered to the Southern region (Giri 2021).

Using the official Thailand tourism I-O table provided by the Thailand Ministry of Tourism and Sports, 23 sectors (see Table 2) pertaining to gastronomic tourism were selected from 89 industrial activities in the 2017 I-O table.

Table 2.

The collected gastronomic tourism I-O sectors based on the 2017 tourism I-O table.

The selected sectors are defined as those that impact gastronomy tourism in Thailand through multiplier effects (Benedek et al. (2020)), because all 23 sectors play a significant role in the food industry, whether upstream, midstream, or downstream. In addition, the food industry supplies food to gastronomy tourism2 when this ecosystem of both moves up together, which empowers the drive for the economy of Thailand to achieve more after its COVID-19-related decline. However, these data will then be processed in the relating to dynamic regional I-O forecasting.

4.2. Result of Dynamic Regional Input-Output Analysis

Based on the high-performance areas identified for as gastronomy tourism destinations, further details can be found in Table 3. This table shows the details of a comparison of dynamic regional multipliers’ predictions between Bangkok and vicinities and the Southern provinces; it is clear that the performance of the capital city and its surrounding neighborhoods in terms of gastronomic tourism destinations is almost higher than that of its counterpart. For example, a premium high productive sector is animal food industries, while high productive sectors include sugar industries, slaughtering companies, even food and beverage serving activities, etc. However, there are some interesting points; for example, state industries manufacturing beans and nuts perform better in the Southern region rather than the capital city because of the lack of farming area in the latter. Moreover, industries producing preserved foods in the Southern region contain the higher multiplier than those in its counterpart because of its greater raw material sources. To summarize, gastronomy tourism in Thailand does not have many options for renewal. Policies to promote gastronomic activities should be initially implemented in the area of the capital city and its neighbors.

Table 3.

The comparison of dynamic multiplier predictions between Bangkok and vicinities and the Southern region in Thailand based on gastronomic sectoral activities.

Regarding the potential areas for gastronomy tourism destinations, more details can be found in Table 4. The results indicate that provinces in the Eastern region perform better overall than those in the Northern region as primary gastronomy tourism destinations. The advantages of the eastern region are sea-connecting and multi-farming provinces such as Chonburi, Rayong, Chanthaburi, and Trad. These provinces have agricultural sectors—paddy, maize, cassava, beans, nuts, and farms for vegetables and fruits—which are essential for driving the downstream of gastronomy tourism. Additionally, beverage and food service companies in the Eastern region are predicted to be more active than those in the Northern region. However, with the lack of agricultural spaces and living costs in the Eastern region, gastronomic activities such as slaughtering, preserved foods, and rice farming perform better in Northern provinces. To summarize this issue, Eastern and Northern areas can be defined as a good choice to continue the sustainable development for gastronomy tourism.

Table 4.

The comparison of dynamic multipliers between the Eastern region and Northern region in Thailand based on gastronomic sectoral activities.

The optional areas for gastronomy tourism destinations are detailed in Table 5. This table provides a clear comparison, demonstrating that the Western region outperforms the Northeastern region in terms of agricultural activities and services related to beverages and food. However, it is noteworthy that there is a significant disparity in the sizes of these regions. The Northeastern region, being the largest in Thailand, comprises more provinces than the Western region (Thailand Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment 2021). Despite this, the economic multipliers of the Northeastern region have only a marginal impact on enhancing gastronomy tourism in the country. In summary, while both regions serve as viable alternatives for gastronomic activities, the Western region offers more value for promoting gastronomy tourism, especially in light of budget constraints. The minor area for gastronomy tourism destinations is detailed in Table 6. The Central region has the lowest multipliers impacting Thailand’s gastronomy tourism. With multiplier values equivalent to one, this implies that investing budgets to initiate gastronomic tourism activities in this region would only achieve break-even development.

Table 5.

The comparison of dynamic multiplier predictions between Northeastern region and West region in Thailand based on gastronomic sectoral activities.

Table 6.

Dynamic multiplier predictions for the Central region in Thailand based on gastronomic sectoral activities.

Therefore, while this region is less ideal for promoting gastronomy tourism, it presents a better opportunity for sustainable development as a provider of raw gastronomic materials for major tourist destination cities.

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

Although gastronomic activities are common and merged into daily life for the Thai people, promoting gastronomy tourism to the flagship in terms of of refreshing the Thai economy after the COVID-19 outbreak is a difficult task in terms of political consideration and decentralized development. It is very clear that Bangkok is the most popular city and the signature for Thailand’s gastronomy tourism. However, Bangkok is just a small area that can only provide short-term tourism, meaning a short trip by low-cost travelers. Consequently, this issue is what has inspired the authors to apply dynamic regional I-O analysis to clarify the unsustainable development of gastronomy tourism in Thailand. When we move our attention to regional monitoring, there are many areas in Thailand that have yet to be developed as valuable destinations of gastronomic activities.

The South of Thailand is the leader in terms of ocean-gastronomic areas. Considering the north of Thailand, this area can be defined as ‘truly forest’. Many unique foods from unique tribes here are the key to refreshing the sustainability of long-term travel. The Western and Northeastern regions present a good opportunity for renewal due to the combination of local lives with local foods. Through their connectivity with neighboring countries, these two areas have potential in multi-national gastronomy tourism. The Central region is indicated as a last option, but this is an interesting region that can be promoted in terms of ‘historical gastronomy activity’, which can be a locally-generated source of national incomes from downstream production lines.

The conclusion of this article is that gastronomy tourism is the solution for reversing Thailand’s economic depression caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Gastronomic activities are deeply linked to the power of purchasing by domestic tourists, which is the only way to rescue local small businesses in the tourism sector. The dynamic regional I-O model is not a novel econometric application, but it can efficiently help to monitor the whole economic system with trustworthy information inputs. The recent economic sectors of tourism in Thailand, based on the structure of the tourism economy, were constructed using the 2017 tourism I-O table database. This database is officially provided by the Thailand Ministry of Tourism and Sports and serves as the main source for this paper. Assuming that the pandemic is less impactful, the results strongly suggest that Thailand’s gastronomic tourism can have a positive impact on other economic sectors, particularly after the economic downturn caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. This is because gastronomic activities have an influence on both downstream and upstream production lines.

The main policy recommendation of this research study is to stimulate gastronomic tourism in several regions of Thailand through digital tourism platforms (Sigala 2020; Bekele and Raj 2024). These platforms aim to connect tourists with local gastronomic experiences, particularly in the Northeastern, Central, and Western regions of Thailand (see Table 5 and Table 6). This is necessary because both regions have a lower I-O multiplier compared to other regions in Thailand. Furthermore, it is crucial for both the public and private sectors to collaborate with food bloggers, chefs, and social media influencers to create an ecosystem that promotes Thai gastronomy and covers every regional part of Thailand extensively (Gursoy and Chi 2020; Kiráľová and Malec 2021). Because of the experience of COVID-19, the significant part of policies regarding the gastronomic tourism industry for every region of Thailand must focus on health and safety protocols in order for all gastronomic tourism activities to boost demand and supply in sustainable gastronomic tourism (Baum and Hai 2020).

Moreover, the tourism industry in Thailand has grown very quickly, but there has been a lack of balance in its progress for a long time, especially in the development of gastronomy tourism. Based on data from 2019, gastronomy tourism in Thailand contributes significant income to the Thai economy. It was found that only two regions, Bangkok & Vicinities and Southern Thailand, contributed income to the Thai economy. However, this research is consistent with this report as well, because the overall multipliers of the food industry in these regions were the highest compared to other regions of Thailand (see Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6).

The second policy recommendation aims to enhance digital marketing to promote and support the distinctive aspects of gastronomy tourism in every region of Thailand, ensuring a fair distribution of economic benefits throughout the country (Thirumoorthi and Sedigheh 2021).

For future research, an updated tourism I-O table would provide a more accurate representation of the realities of gastronomic tourism in the country, which is the limitation of this study. However, the new updated tourism I-O table for Thailand will be announced soon3, and it will be more precise in computing the multiplier of the food industry’s impact on gastronomy tourism and would be more appropriate for examining its economic impact for future studies. This research article used a specific tourism I-O table from 2017, one that was recently updated in Thailand4. Normally, the I-O table must be surveyed to collect data every 5 years as per the standard in Thailand5. This is because the I-O table assumes that the economic structure changes slowly every 5 years6.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.T.; methodology, B.T.; software, C.C.; validation, N.K.; formal analysis, N.K.; investigation, B.T.; resources, B.T. and C.C.; data curation, B.T.; writing original draft preparation, C.C. and B.T.; writing review, N.K.; editing, W.C.; visualization, B.T.and C.C.; supervision, W.C. and C.C.; project administration, W.C.; funding acquisition, W.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially supported by Chiang Mai University [R66IN00331].

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

MQERC, Faculty of Economics, Chiang Mai University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | See https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 29 May 2024). |

| 2 | See https://www.unwto.org/gastronomy-wine-tourism (accessed on 29 May 2024). |

| 3 | See https://www.mots.go.th/mots_en (accessed on 29 May 2024). |

| 4 | See https://www.mots.go.th/news/category/433# (accessed on 29 May 2024). |

| 5 | See https://www.nesdc.go.th/more_news.php?cid=570&filename=io_page (accessed on 29 May 2024). |

| 6 | See https://apps.bea.gov/scb/issues/2020/12-december/1220-reprint-input-output-tables.htm (accessed on 29 May 2024). |

References

- Baum, Tom, and Nguyen Thi Thanh Hai. 2020. Hospitality, tourism, human rights and the impact of COVID-19. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 32: 2397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, Henok, and Sahil Raj. 2024. Digitalization and digital transformation in the tour-ism industry: A bibliometric review and research agenda. Tourism Review, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedek, Zsófia, Imre Fertő, and Viktória Szente. 2020. The multiplier effects of food relocalization: A systematic review. Sustainability 12: 3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brankov, Jovana, Ivana Penjišević, Nina B. Ćurčić, and Branko Živanović. 2019. Tourism as a Factor of Regional Development: Community Perceptions and Potential Bank Support in the Kopaonik National Park (Serbia). Sustainability 11: 6507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaitip, Prasert, and Chukiat Chaiboonsri. 2009. Thailand’s international tourism demand: The ARDL approach to cointegration. Annals of the University of Petrosani: Economics 9: 163–84. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, Larry, Peter Forsyth, and Wayne Dwyer. 2010. Tourism Economics and Policy. Bristol: Channel View Publications. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. 2020. Sustainable Food and Agriculture. Available online: https://www.fao.org/sustainability/background/en/ (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Giri, Kalpana. 2021. Initial assessment of the impact of COVID-19 on sustainable forest management: Asia-Pacific States: A case study on Thailand and Nepal. In United Nations Forum on Forests Secretariat. New York: United Nations. Available online: https://www.un.org/esa/forests/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/COVID-19-SFM-impact-AsiaPacific.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Gursoy, Dogan, and Christina G. Chi. 2020. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on hospitality industry: Review of the current situations and a research agenda. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management 29: 527–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardadi, Gilang, and Massimo Pizzol. 2017. Extending the multiregional input-output framework to labor-related impacts: A proof of concept. Journal of Industrial Ecology 21: 1536–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isard, Walter. 1951. Interregional and regional input-output analysis: A model of a Space-economy. The Review of Economics and Statistics 33: 318–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiráľová, Alžbeta, and Iveta Hamarneh. 2017. Local gastronomy as a prerequisite of food tourism development in the Czech Republic. Marketing and Management of Innovations, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiráľová, Alžbeta, and Lukáš Malec. 2021. Local food as a tool of tourism development in regions. International Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management in the Digital Age (IJTHMDA) 5: 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronenberg, Kai, Matthias Fuchs, and Maria Lexhagen. 2018. A multi-period perspective on tourism’s economic contribution—a regional-input-output analysis for Sweden. Tourism Review 73: 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Juanita C., and Turgur Var. 1986. Resident attitudes toward tourism impacts in Hawaii. Annals of Tourism Research 13: 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Ronald E., and Peter D. Blair. 2009. Input–Output Analysis: Foundations and Extensions, 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, Ross E., and Donald G. Reid. 2001. Community integration: Island tourism in Peru. Annals of Tourism Research 28: 113–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachão, Susana, Zélia Breda, Carlos Fernandes, and Veronique Joukes. 2019. Food tourism and regional development: A systematic literature review. European Journal of Tourism Research 21: 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, Sergio J. 2000. Integrated regional econometric and input-output modeling. Papers in Regional Science 79: 271–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, Chiara. 2017. Food and gastronomy for sustainable place development: A multidisciplinary analysis of different theoretical approaches. Sustainability 9: 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, Joost R. 2005. Inoperability input-output modeling of disruptions to interdependent economic systems. Systems Engineering 9: 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargento, Ana Lúcia Marto. 2009. Regional Input-Output Tables and Models. Interregional Trade Estimation and Input-Output Modelling Based on Total Use Rectangular. Coimbra: University of Coimbra. Available online: https://estudogeral.uc.pt/bitstream/10316/10120/3/Regional%20io%20tables%20and%20models_cd%20pdf%20file.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- Sigala, Marianna. 2020. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. Journal of Business Research 117: 312–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stadler, Konstantin, Richard Wood, Tatyana Bulavskaya, Carl Johan Södersten, Moana Simas, Sarah Schmidt, Arkaitz Usubiaga, José Acosta-Fernández, Jeroen Kuenen, Martin Bruckner, and et al. 2018. EXIOBASE 3: Developing a time series of detailed environmentally extended multi-regional input-output tables. Journal of Industrial Ecology 22: 502–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TAT. 2019. Tourism Markeing Campaign. Bangkok: TAT. [Google Scholar]

- Thailand Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment. 2021. Thailand Forest Statistics 2020. Available online: http://forestinfo.forest.go.th/Content.aspx?id=10400 (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Thailand Ministry of Tourism and Sports. 2019. Tourism Statistics 2019. Available online: https://www.mots.go.th/more_news_new.php?cid=521 (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Thailand Ministry of Tourism and Sports. 2020. Tourism I-O Table. Available online: https://www.mots.go.th/more_news_new.php?cid=433 (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Thirumoorthi, Thinaranjeney, and Moghavvemi Sedigheh. 2021. Digital marketing and gastronomic tourism. In The Routledge Handbook of Gastronomic Tourism, 1st ed. London: Routledge, p. 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. 2013. Creative Economy Report 2013 Special Edition. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000224698 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- United Nations. 2020. Sustainable Gastronomy Day 18 June. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/observances/sustainable-gastronomy-day (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- World Health Organization. 2020. The Ministry of Public Health and the World Health Organization review Thailand’s COVID-19 Response. Available online: https://www.who.int/thailand/news/detail/14-10-2020-Thailand-IAR-COVID19 (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Zhang, Bo, Z. M. Chen, Li Zeng, Han Qiao, and Bin Chen. 2016. Demand-driven water withdrawals by Chinese industry: A multi-regional input-output analysis. Frontiers of Earth Science 10: 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, Karl, André Schröder, and Jesko Hirschfeld. 2013. A regional dynamic input-output model of tourism development in the light of climate change. In Beiträge zum Halleschen Input-Output-Workshop 2012. IWH-Sonderheft 1/2013. Halle: Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung Halle. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).