Abstract

This study extends the concept of granularity from firms to cities, examining how large cities influence national economic dynamics beyond their relative size. By applying Zipf’s law, which describes the power law distribution of city sizes, we investigate the interplay between granularity and business cycles. Our aim is to test the granular hypothesis that large cities have a significant impact on the business cycle beyond their relative size. We analyze data from American and Brazilian cities between 2003 and 2019 assessing the granular residuals and their explanatory power. Our findings reveal that in the United States, the granular city size is three metropolitan areas or five counties when redefined. In Brazil, it equates to three municipalities. These results emphasize the substantial role large cities play in national economic fluctuations, suggesting that policy interventions that target infrastructure, education, and innovation in major urban centers could have widespread economic benefits. This paper’s contribution to the literature is to highlight a spatial component of granularity not considered so far.

1. Introduction

Cities are considered one of humanity’s greatest inventions as they bring people closer, facilitating connections and the exchange of information, leading to the emergence of new ideas and innovations (Glaeser 2011). Our hypothesis is that large cities play a crucial role in the business cycle beyond their relative size. To test this hypothesis, we apply the concept of “granularity”, originally used in the context of firms (Gabaix 2011).

In the United States, urban management policies have played a pivotal role in shaping the economic dynamics of cities. The federal and state governments have implemented various policies to promote urban development, improve infrastructure, and enhance the quality of life in urban centers. For instance, the implementation of the Community Development Block Grant program has provided cities with funding to address housing, economic development, and infrastructure needs. Similarly, the establishment of Enterprise Zones has incentivized businesses to invest in economically distressed areas, leading to job creation and economic revitalization.

In Brazil, urban management policies have focused on addressing the challenges posed by rapid urbanization and promoting sustainable urban development. The Statute of the City, enacted in 2001, provides a comprehensive legal framework for urban planning and land use management. It aims to ensure social inclusion, environmental sustainability, and equitable access to urban resources. Additionally, the Growth Acceleration Program has focused on improving urban infrastructure, including transportation, housing, and sanitation, to support economic growth and enhance the quality of life in Brazilian cities.

The role of urban management policies in shaping the economic dynamics of cities shows the importance of considering policy interventions when analyzing the impact of large cities on the business cycle. Urban management policies can influence the spatial distribution of economic activities, the integration of cities into the national economy, and the resilience of urban centers to economic shocks.

By examining the interplay between granularity and urban management policies, our study provides a comprehensive understanding of the factors driving economic dynamics in large cities. This integrated approach contributes to the broader literature on urban economics and offers valuable insights for policymakers aiming to harness the economic potential of large cities while addressing the challenges associated with urbanization.

Granularity within firms refers to the coexistence of a few large firms alongside numerous smaller ones. An economy is considered “granular” due to this diversity; if all firms were the same size, it would be “smooth”. The “granular residual” is the cumulative effect of individual firm-specific shocks, weighted by their respective sizes. This term emphasizes the portion of the business cycle that cannot be explained by macroeconomic shocks alone and underscores the significance of microeconomic shocks unique to each firm. The granular residual captures the impact of shocks to the largest firms, accurately assessed by considering the “granular size”.

The presence of significant “grains” necessitates a heavy right tail in the size distribution of firms. This power law tail enables these large grains to impact the business cycle in ways that a continuum of equally sized firms cannot. When the firm size distribution follows a heavy-tailed pattern, idiosyncratic shocks affecting the largest firms should not average out at the aggregate level. Instead, they are expected to influence GDP dynamics. Similarly, in cities, we observe a similar pattern where a few cities are significantly larger than the majority of smaller cities (Zipf’s law). Consequently, idiosyncratic shocks to large cities may not be fully compensated by opposing shocks to smaller cities. If all firms were the same size and reacted similarly to shocks, the granular residual would be zero. However, if large firms are more susceptible to shocks, the granular residual can be substantial.

Zipf’s law (Zipf 1949) characterizes a power law distribution of city populations, where population is inversely related to rank. Although Zipf’s law predates and is separate from the concept of granularity, both approaches acknowledge hierarchical patterns in urban systems. We highlight that granularity and Zipf’s law are closely related, as the heavy-tailed distribution inherent in hierarchical quantities allows for the presence of exceptionally large units.

Growth rates exhibit correlation with individual unit shocks (firms or cities) (Gabaix 2011; Dosi et al. 2019). Hence, these shocks can be viewed as growth rates for cities. The majority of the business cycle can be explained by growth, wherein recessions occur when significant units experience below-average growth, while booms witness the opposite. Consequently, idiosyncratic shocks serve as growth rates for cities. The level of integration of a city into the national economy determines the extent of spillover effects on other cities within the country. This integration, in turn, improves the explanatory power of the granular residual. Various factors contribute to the differential growth rates of cities compared to the national average, such as the discovery of natural resources, the emergence of innovation hubs, changes in building codes, the arrival of multinational corporations, or substantial state investments. The key insight is that a greater integration of a city into the national economy amplifies spillover effects, consequently intensifying the explanatory power of the granular residual.

The city–firm analogy finds justification in the fact that despite advancements in technology facilitating information transmission, direct human contact remains highly efficient due to centuries of human development. This efficiency improves the benefits of human agglomeration in confined geographical areas, making new information technologies complementary to physical proximity. Consequently, the largest and most innovative companies tend to locate near dense populations, capitalizing on the knowledge flows and opportunities for economic growth facilitated by large cities. This positive feedback process reinforces the emergence of exceptionally large cities (Glaeser 2011).

The rationale behind Zipf’s law for cities, which states that city sizes (in terms of population) follow a power law with an exponent of one, can thus be justified. However, alternative interpretations exist (Rauch 2014), as Zipf’s law lacks a sufficient theoretical explanation and is not accounted for by standard urban system models (Krugman 1996). A random growth model may adequately explain it (Simon 1955), or it might not require any theoretical justification at all (Mandelbrot 1961). It is plausible that city location is fundamentally random, with city size unaffected by interactions with other cities (Ioannides and Overman 2004). A meta-analysis of 515 estimates from 29 studies indicates that the Zipf coefficient exceeds one and that cities are more evenly distributed than suggested by Zipf’s law (Nitsch 2005). Chauvin et al. (2017) provide a concise overview of the ongoing debate surrounding Zipf’s law.

However, previous authors, including Zipf (1949), Krugman (1996), Gabaix (1999), and Dobkins and Ioannides (2001), have shown the presence of Zipf’s law in various U.S. databases. Zipf’s analysis focused on the top 100 metropolitan areas in the United States in 1940, calculating a power law with a slope of approximately one (−0.9835 ± 0.0625) based on the rank–frequency distribution. We replicate Zipf’s law using a more recent dataset that includes not only metropolitan areas but also counties in the United States. It would be interesting to compare this conclusion to those obtained for an emerging economy. While Rozman (1990) shows Zipf’s law for China in the mid-1800s, we were unable to obtain the specific data required to calculate the granular residual for recent China data. However, we found data from Brazil, an emerging country. Gabaix (1999) attributes Zipf’s law to the growth processes observed in cities in the upper tail (referred to as Gibrat’s law) and the diminishing decline in shocks with size beyond a certain threshold. Although Giesen and Sudekum (2011) confirm this hypothesis for German cities, it fails to hold for a broader sample of U.S. cities from 1900 to 1990 (Black and Henderson 2003). Nevertheless, we argue that Gabaix’s insight emphasizes the interrelation of the power law and granularity, motivating our investigation into granular cities.

Therefore, considering the insights from Glaeser (2011) and Gabaix (1999, 2011), it is plausible to hypothesize that the business cycle primarily occurs in large cities. If it were the opposite, small cities would have a more significant impact on the business cycle, resulting in symmetric cycles of rise and fall. Our hypothesis carries a crucial implication: economic growth spreads from large cities to smaller ones. Gabaix and Koijen (2020) propose that evaluating the granular hypothesis also allows us to test various types of spillovers. When large cities foster innovative developments linked not only to the business cycle but also long-term economic growth (Glaeser 2011), such growth is expected to disseminate to smaller cities, strongly influencing a country’s production fluctuations. Metropolitan areas often encompass multiple municipalities, making it challenging to separate the economic growth of specific municipalities from their surroundings. Hence, we examine counties and metropolitan areas, rather than focusing solely on municipalities, to account for these complexities.

Studying the business cycle at the city level involves examining economic fluctuations and patterns within specific urban areas. The concept of granularity aligns well with this endeavor, offering a comprehensive understanding of localized impacts and economic dynamics. While the business cycle is typically analyzed at the national or regional level, studying it at the city level provides a more detailed perspective. It allows for the exploration of the relationship between the city-level business cycle and broader macroeconomic factors, including national economic conditions, policies, international trade, and global trends. Such analysis holds practical implications for policymakers, urban planners, and businesses. It aids in identifying economic strengths and vulnerabilities, designing targeted policies to stimulate growth or address downturns, and assessing regional disparities within a country’s economy.

As observed, to ensure the generalizability of our findings, we analyze data from both a developed country (the United States) and an emerging country (Brazil). We test the granular hypothesis using data from counties, metropolitan areas, and municipalities in these countries spanning from 2002 to 2019. Our hypothesis is stated as follows:

Hypothesis 1.

Larger cities in the United States and Brazil explain a greater proportion of the business cycle than their relative size.

If this hypothesis holds true, it implies the existence of granular cities, similar to granular firms discussed in the literature, which explain the business cycle in both the U.S. (Gabaix 2011) and Brazil (Silva and Da Silva 2020).

Our study builds upon the foundational work of Glaeser (2011) and Gabaix (2011) by extending the concept of granularity from firms to cities, thereby providing a new spatial perspective on urban economic dynamics. Glaeser emphasized the economic significance of cities as centers of innovation and growth, while Gabaix introduced the idea of granularity to explain the disproportionate impact of large firms on the business cycle. By applying these concepts to cities, we show that large urban centers play a similarly crucial role in national macroeconomic fluctuations.

This research diverges from previous studies by focusing on the city level rather than the firm level, offering a novel application of granularity in macroeconomics. Unlike traditional macroeconomic models that often treat cities as homogenous entities, our approach highlights the unique contributions of large cities to national economic dynamics. This perspective aligns with Zipf’s law, which describes the power law distribution of city sizes and emphasizes the presence of a few exceptionally large cities that significantly influence the overall economic landscape.

Moreover, our empirical validation across different countries, specifically the United States and Brazil, improves the robustness and generalizability of our findings. Our inclusion of an emerging economy like Brazil provides a broader understanding of how granularity manifests in diverse economic contexts. This comparative analysis reveals that despite differences in urban management policies and economic structures, the impact of large cities on national business cycles is a consistent phenomenon.

This paper’s structure is as follows: (1) We replicate Zipf’s law for our dataset using Gabaix and Ibragimov (2011)’s methodology. (2) We test the granular hypothesis, examining whether large cities contribute more to the business cycle relative to their size. (3) We calculate the granular size of cities. Here, we use Blanco-Arroyo et al. (2018)’s methodology to compute the granular size of American and Brazilian cities. (4) We compare our findings between the two countries and with the existing literature on firms.

Overall, this paper’s originality lies in its novel application of the established concept of granularity to cities, the introduction of a new spatial perspective, and the empirical validation of this approach across different countries. We offer a novel perspective that bridges urban economics and macroeconomic analysis, providing insights that have not been previously explored in the literature.

2. Methodology

2.1. Data

Cities can be defined in various ways. A narrow definition sees cities as municipalities with specific boundaries and governing bodies. A broader definition includes metropolitan areas, which encompass a central city, suburbs, and interconnected urban and suburban regions. This definition acknowledges that cities extend beyond a single administrative unit and considers economic and social relationships between the center city and its surroundings. Legally defined cities such as counties or municipalities are typically not ideal for economic analysis unless there is a compelling reason. The availability of data justifies including counties and municipalities in our study. Furthermore, we consider metropolitan areas and obtain significant results especially for the United States.

One advantage of our approach is its ability to capture the economic impact of idiosyncratic shocks to large cities, which may not be fully addressed by traditional macroeconomic models. By applying the granular residual method, we can specifically account for the significant influence of large urban centers on national economic fluctuations. This approach allows for a more detailed analysis of localized economic dynamics compared to other techniques that might overlook the unique contributions of individual cities. Additionally, our methodology leverages high-resolution data on population and economic output, enabling a more precise assessment of urban economic contributions. By incorporating Zipf’s law and granularity, we provide a novel perspective that bridges urban economics and macroeconomic analysis, offering insights that are both theoretically robust and practically relevant for policymakers.

To compute the granular residual, population and economic output data are essential (Gabaix 2011). In the United States, we have access to output data for counties and metropolitan areas, so we consider both. The Census Bureau provides such GDP data. In Brazil, the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics releases GDP data for municipalities only. However, with the municipality-level data available, we can calculate population and GDP for 82 Brazilian metropolitan areas. Thus, we analyze data in four ways: (1) U.S. counties, (2) U.S. metropolitan areas, (3) Brazilian municipalities, and (4) Brazilian metropolitan areas. The examination covers population and economic output for both countries, spanning from 2002 to 2019. The datasets can be found on Figshare.

Table A1 in Appendix A presents the most populous counties in the United States. Over the period of 2002 to 2019, Los Angeles County had a population more than ten times larger than DuPage County, IL, which ranked 51st. Similarly, Table A2 in Appendix A displays the 51 largest metropolitan areas in terms of population during the same period. The largest metropolitan area, New York–Northern New Jersey–Long Island, was approximately 18 times larger than the 51st, Rochester. Moving on to Table A3, it showcases the largest Brazilian municipalities based on the average population between 2002 and 2019. Out of around 5570 Brazilian municipalities, São Paulo, the largest one, accounted for nearly 5% of the national population and was almost 27 times the size of Santos, the 51st largest municipality. Lastly, Table A4 reveals the 51 largest Brazilian metropolitan areas out of a total of 82. The contrast is even more significant for metropolitan areas. Greater São Paulo, the largest metropolitan area, had a population approximately 56 times larger than Toledo, the 51st on the list.

Table A5 and Table A6 in Appendix A present descriptive statistics for the four subsets of data. These statistics cover the 200 largest American counties and Brazilian municipalities with over 100,000 average inhabitants between 2002 and 2019, as well as all metropolitan areas in the United States and Brazil. The statistics exclude extreme shocks in terms of growth rates but retain population outliers. We found that outliers greatly influenced the results when calculating growth rates, specifically impacting asymmetry, kurtosis, and the Jarque–Bera test. To address this, we removed growth rate outliers with absolute z-scores exceeding 2 from the sample. For this reason, Table A5 and Table A6 display the population and growth rate descriptive statistics based on samples of varying sizes.

The Jarque–Bera test assesses the Gaussianity of the test statistic, which follows a chi-square distribution with two degrees of freedom. The critical value at a 5% significance level is 5.99. Across the four datasets, we reject the null hypothesis that cities are normally distributed when ordered by population. This aligns with the expected outcome if cities adhere to Zipf’s law. However, growth rates are normally distributed for American counties, metropolitan areas, and Brazilian municipalities. Therefore, we anticipate the granular hypothesis to hold for these subsamples. The normality hypothesis for growth rates in Brazilian metropolitan areas is rejected, suggesting a deviation from the granular hypothesis. In these cases, the estimated values in the Jarque–Bera test exceed the critical value of 5.99. These findings reflect the requirement for population to follow a power law in order to test the granular hypothesis, while growth rates are not necessarily characterized by heavy tails (Dosi et al. 2019).

2.2. Zipf’s Law

The size distribution of cities, according to Zipf’s law, follows a power law: the number of cities with populations greater than x is proportional to 1/x (Gabaix 1999). To test for the presence of power laws in all subsets of population data, we obtain ordinary least squares (OLS) estimates of the tail exponents employing the rank – ½ method of Gabaix and Ibragimov (2011). Thus, we take

where populationi is the mean population for the cities in the samples from 2002 to 2019 for both countries, ranki is the rank from highest to lowest according to the size of populationi, and populationm is the lowest bound used as a cutoff to analyze the tail. To estimate the Pareto exponent using OLS regression, researchers commonly run the regression and take b as the estimate of the Pareto exponent. However, this approach can be biased, particularly in small samples. To reduce this bias, Gabaix and Ibragimov introduced their modified method that uses rank − ½ instead of rank. For additional robustness, we also estimate Pareto exponents using maximum likelihood in Appendix C, following the method of Clauset et al. (2009).

A power law occurs between a minimum cutoff and a maximum threshold because few distributions follow a power law over their entire range. This is why a distribution is said to have a power law tail (Newman 2005). α in Equation (1) is the tail index (Pareto exponent) and measures the weight of the right tail, with smaller values indicating heavier tails (Jenkins 2017). The aggregate fluctuations in heavy-tailed distributed data are not proportional to , as would be expected if the data were Gaussian-distributed. Granular shocks are proportional to instead (Gabaix 2011). As a result, shocks to large cities are not offset, and economic growth spillovers are substantial.

2.3. The City Granular Residual

The granular residual quantifies the impacts of shocks to major companies at the individual firm level, as observed. An important implication is that when regressing a country’s growth rate on the granular residual of its largest companies, the adjusted R2 will exceed the companies’ share of GDP. This suggests that shocks, specifically those related to productivity, affecting large corporations play a substantial role in shaping the business cycle (Gabaix 2011).

Similar to Gabaix’s firm granular residual, we define the granular residual for K cities as

where city populationi,t is the population of city i at time t, country populationt is the country population at time t, is city i’s per capita output growth rate at time t, and is the country’s per capita GDP growth rate at time t. To compute , we add up the residuals of the cities. Then, we run an OLS regression of the country’s per capita GDP growth rate on the granular residual . The adjusted R2 value is expected to be greater than the percentage of the country’s population represented by such cities in the presence of granular effects (Gabaix 2011). In this case, we do not reject our previously stated hypothesis.

The granular residual’s contribution assesses the extent to which shocks impacting large cities influence a country’s overall economic dynamics. It suggests that the effects of shocks experienced by large cities may not be entirely counteracted by opposing effects in smaller cities. This underscores the significance of comprehending the specific dynamics and characteristics of individual cities when explaining a nation’s overall economic fluctuations. Essentially, the granular residual for cities implies that shocks originating from large cities have a greater influence than what can be accounted for by their relative size alone. This encompasses the integration of large cities into the national economy and the potential spillover effects on other cities within the country.

According to the standard method in the business cycle literature, after demonstrating how granular cities can explain the business cycle, the next step should be to evaluate the impact of a few cities on aggregate volatility (the second-order moment). However, following the granularity literature, our analysis does not extend to this level of detail.

The link between city population size and economic output is well supported in urban economics and economic geography. Key points include the following: (1) Larger cities can provide services like transportation and healthcare more efficiently, spreading costs over a larger population, which may reduce per capita costs (economies of scale) (Glaeser 2011). (2) The concentration of people and firms in big cities boosts productivity through knowledge spillovers, labor market pooling, and improved access to suppliers and customers, enhancing output and innovation (Duranton and Puga 2004). (3) Larger cities attract a wide range of skills, helping firms find suitable employees and boosting productivity (Florida 2019). Thus, improvements in technological efficiency and innovation contribute to increased labor productivity, the key measure we employed for calculating shocks. (4) This diversity in bigger cities drives innovation by bringing together varied perspectives and expertise (Jacobs 1970). (5) Larger cities often see more development and investment in infrastructure, supporting business operations and contributing to higher economic output (Bettencourt et al. 2007).

Although there are reasons to link city population size with economic output, this relationship is intricate and shaped by factors like the city’s industrial makeup, geographical position, policies, and history. Additionally, bigger cities often contend with issues such as higher living costs, traffic congestion, and environmental challenges. Nevertheless, empirical research consistently indicates a positive correlation between a city’s size and its economic performance, with larger cities typically having higher per capita GDP than smaller cities or rural regions (Glaeser 2011; Bettencourt et al. 2007; Rosenthal and Strange 2004).

Replacing economic output with city population size in modeling is challenging. Specifically, in granular Equation (2), we need to factor in the Domar weight multiplied by idiosyncratic shocks. Originating from Hulten’s theorem and explored in Gabaix (2011), this approach is based on an input–output economy framework. The Domar weight, defined as a firm’s gross output relative to total GDP, indicates its contribution to overall output or productivity, typically in economies with intermediate inputs and networks. However, applying this concept to cities, where the links between intermediate goods among different cities are less clear, presents difficulties. In Equation (2), the Domar weight should represent a city’s gross output as a proportion of GDP, not its population share. While the g − G component still quantifies the effect of a city’s growth shock, it is important to note that unlike firms, which directly contribute to aggregate output, cities function as hubs that attract labor and businesses. The literature includes a few examples of studies related to this modeling task. Hsieh and Moretti (2019) used a spatial equilibrium model to measure the extent and aggregate costs of labor misallocation across U.S. cities. Duranton and Puga (2023) created a microfounded urban growth model in which human capital spillovers promote entrepreneurship and learning in heterogenous cities. They used this model to explore different hypothetical scenarios, quantitatively evaluating the impact of cities on economic growth and overall income.

In Appendix B, we examine the granular hypothesis by using the previous year’s GDP (t − 1) as the share for calculating this year’s (t) granular residual. The findings indicate that the impact of large grains on GDP is not solely due to their larger GDP size. Thus, the role of population is crucial in understanding how large grains affect the business cycle.

2.4. The Granular City Size

To accurately assess a city’s granular residual contribution, it is crucial to calibrate using the granular city size K* in Equation (2). We evaluate the explanatory power of the city granular residual by comparing a weighted curve (as defined in Equation (2)) with an equal-weighted curve. The equal-weighted curve assumes all cities are of the same size and follows a methodology introduced by Blanco-Arroyo et al. (2018) for determining the granular size of firms. This ensures that the estimation of a city’s granular residual is not underestimated or overestimated.

Therefore, to accurately analyze the granular residual contribution of cities, it is important to consider the granular city size in the analysis, achieved through a calibration procedure. The calibration aims to strike a balance by including enough cities to capture meaningful variation while excluding cities that may introduce irrelevant information. An insufficient inclusion of cities may lead to an underestimation of the granular residual contribution, as significant variations in excluded cities are overlooked. Conversely, an excessive number of cities may result in an overestimation, as noise from less economically significant cities dilutes the overall signal. By calibrating the analysis, we identify a subset of cities that provide a representative sample, mitigating biases arising from too few or too many cities. This approach enables a more accurate evaluation of the explanatory power of the granular residual by comparing observed granular residuals to a hypothetical curve with equal weights assigned to all cities, treating them as if they were of equal size.

The “granular curve” of function C(L) of the average cumulative explanatory power is

where Q is an arbitrary number of cities, and L is the number among the best-ranked cities that should be removed from the sample and replaced by the Q + 1, …, Q + L best-ranked. Thus, for each L, the same number of regressions is calculated, with the granular residual (with the weights attributable to population size) as the only explanatory variable. C(L) indicates the average R2, in each L, for Q regressions performed. Therefore, the idea is to examine the sensitivity of R2 to a sequential exclusion of the largest cities, which means increasing L. So, we consider the explanatory power curve as a function of an increasing number of cities K and for different values of the largest cities L. We want to see how the curve performs depending on the number L of highest-ranked cities that are removed from the sample and replaced by the Q + 1, …, Q + L following cities. Moreover, we run the same number Q of regressions with the granular residual as the explanatory variable for each L. And C(L) refers to the average R2 in every L for Q regressions performed.

In parallel, we must run the same regressions without weights, which means ignoring the population size weights. The granular size is obtained when the granular curve C(L) equals the adjusted R2 of the regressions without weights. In general, the granular size indicates the number of the largest grains that can be removed from the sample without affecting the average explanatory power (adjusted R2) of the granular residual for various possible K ≤ Q.

In short, the equal-weight curve quantifies the contribution of shocks to the business cycle from cities as if they were all the same size, with negligible cities playing a larger role. As we gradually remove the L largest cities from the granular residual, we expect to see the transition from the granular curve C(L) to the equal-weight curve. The number L where the granular curve C(L) first intersects the equal-weight curve corresponds to the granular city size K*.

We streamline the computation into three steps to avoid running several thousand regressions:

- We define Q for each case as 1.5 the value of K from which the adjusted R2/population size ratio is below 1; that is, Q = 36 for U.S. counties, and Q = 18 for U.S. metropolitan areas, and Q = 15 for Brazilian municipalities.

- We run regressions for L in threes (L = 3, L = 6, etc.) until the curves with and without weights intersect. We also run regressions with K in threes.

- We compute C(L) and the regressions for the intermediate values of L to find the granular size when C(L) with weights is less than R2 without weights.

3. Results

3.1. Power Law

Table 1 presents the estimation of Equation (1) for American counties across different cutoffs from 2002 to 2019. The high adjusted R2 values suggest that the population distribution of American counties may follow a power law or potentially Zipf’s law. Notably, the α values in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 are approximately one, which supports the literature’s conclusion that the Pareto exponent is greatly influenced by the definition of city and the sample size (Rosen and Resnick 1980).

Table 1.

Power law for the U.S. counties.

Table 2.

Power law for the U.S. metropolitan areas.

Table 3.

Power law for the Brazilian municipalities.

Table 4.

Power law for the Brazilian metropolitan areas.

Based on the adjusted R2 values from different cutoffs for U.S. metropolitan areas (Table 2), we find no evidence to reject the hypothesis that population distributions adhere to a power law. In most cases, the estimated Pareto exponent is near −1, suggesting that the distribution of metropolitan areas potentially follows Zipf’s law, similar to Gabaix (1999)’s sample.

In the Brazilian data, power laws are also observed. Table 3 indicates that the proximity of −1 for most cutoffs prevents us from dismissing the notion that municipality sizes from 2002 to 2019 adhere to a power law. Specifically, the distribution potentially aligns with Zipf’s law, supported by the high adjusted R2 values.

The presence of high adjusted R2 values suggests that the distribution of Brazilian metropolitan areas may conform to a power law. Additionally, Pareto exponents close to −1 indicate the presence of Zipf’s law (Table 4). The findings in Table 3 and Table 4 align with the previous literature (Chauvin et al. 2017).

In Appendix C, following Clauset et al. (2009)’s method, we estimate Pareto exponents with maximum likelihood and compare power law to exponential distributions, both derived using maximum likelihood. While maximum likelihood estimates differ from those by ordinary least squares, their ratio is consistent across the four datasets. Except for Brazilian metropolitan areas, the power law distribution is more likely to describe the data than the exponential distribution.

3.2. Granular Residual

Table 5 displays the results for the largest U.S. counties. In the range of K = 3 to K = 25, the R2/population ratio is positive and greater than one, indicating the statistical significance of the estimated granular residual at a 5% level. Interestingly, the adjusted R2 is consistently higher than the county population/country population ratio for K values from 3 to 25. Hence, we cannot dismiss the granular hypothesis. Notably, the highest R2 value (0.53) is observed at K = 6, including counties such as Los Angeles, Cook, Harris, Maricopa, San Diego, and Orange, CA. However, when considering only the granular residual of Los Angeles County, the adjusted R2 turns negative. To address this, we replace Los Angeles County with Maricopa County and rerun the regressions for the largest counties in each region, resulting in an adjusted R2 of 0.34. Additionally, noteworthy contributions to the R2/population ratio come from Cook, Harris, and Maricopa counties, achieving an adjusted R2 of 0.47 for 4.23% of the population, with an R2/population ratio of 11.3, surpassing any other county.

Table 5.

The granular residual of the U.S. counties.

In the context of U.S. metropolitan areas (Table 6), the granular hypothesis exhibits stronger explanatory power. In particular, for K values from 1 to 13, the R2/population ratio exceeds one. The New York–Northern New Jersey–Long Island metropolitan area stands out with an impressive adjusted R2 of 0.51, despite accounting for only 6.12% of the population. The impact of New York City is less evident in county-level analysis due to its division into five counties, with Queens ranking as the tenth largest. However, at K = 6 and K = 7, which correspond to the Philadelphia–Camden–Wilmington and Washington–Arlington–Alexandria metro areas, the R2/population ratio increases significantly. Combining these three metro areas with the first New York–Northern New Jersey–Long Island area yields an astonishing adjusted R2 of 0.65, representing 9.84% of the population. These findings suggest that the American Northeast plays a crucial role in explaining the U.S. business cycle. In contrast, the inclusion of the second largest metro area, Los Angeles–Long Beach–Santa Ana, reduces the adjusted R2 to 0.61, indicating that Los Angeles County may bias the granular residual and weaken its explanatory power. Comparing Table 5 and Table 6, metropolitan areas demonstrate a stronger association with the granular residual than counties, potentially indicating a closer connection between the growth of U.S. central cities and their surroundings.

Table 6.

The granular residual of the U.S. metropolitan areas.

Analyzing data from Brazil between 2002 and 2019 (Table 7), the granular hypothesis remains unrefuted. Among the 281 municipalities with over 100,000 people on average during this period, the adjusted R2 exceeds the population ratio for K values of 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, and 10. Consequently, we cannot dismiss the granular hypothesis when considering Brazilian municipalities. The next step involves identifying these granular municipalities.

Table 7.

The granular residual of the Brazilian municipalities.

To examine the correlation between municipalities within the same Brazilian geographic regions, we selected the five largest municipalities from each region: Curitiba (South), São Paulo (Southeast), Brasília (Midwest), Salvador (Northeast), and Manaus (North). Surprisingly, the adjusted R2 of −0.01 was lower than all other cases in Table 7, indicating that the regional aspect does not significantly impact the granular effect of large municipalities. However, some municipalities, like Rio, Brasília, Manaus, Recife, and Porto Alegre, displayed lower adjusted R2 values (0.02) compared to others. In particular, including São Paulo and increasing K to 6 resulted in an impressive adjusted R2 of 0.40 for a national population share of only 13%, underscoring São Paulo’s crucial role in the Brazilian business cycle.

In Table 8, we shift our focus to Brazilian metropolitan areas and “urban agglomerations” as analysis units. These agglomerations represent extensions of central cities, encompassing neighboring municipalities with shared social and economic relations, urbanization, commuting patterns, and contiguity. However, the results indicate that none of the regressions’ adjusted R2 values surpass the percentage of the population residing in the metro area. As a consequence, we must reject the granular hypothesis for Brazilian metropolitan areas. Additionally, the value is not statistically significant at 10% for any K, emphasizing the limited relevance of the granular residual in explaining the business cycle within these metro areas.

Table 8.

The granular residual of the Brazilian metropolitan areas.

The high adjusted R² values in our analysis emphasize the statistical significance and robustness of our findings. These values indicate the proportion of variance in national economic fluctuations that can be explained by the granular residuals of large cities. The substantial R2 values show that idiosyncratic shocks to major urban centers have a significant impact on the overall business cycle, beyond what would be expected based solely on their relative sizes. This supports our hypothesis that large cities play a crucial role in national economic dynamics, acting as hubs of economic activity and innovation. The consistency of these high R2 values across different datasets and methodologies reinforces the validity of our approach and highlights the importance of considering city-specific factors in macroeconomic analysis. Our results suggest that policies aimed at improving infrastructure, education, and innovation in major urban centers could have widespread economic benefits, further emphasizing the need for targeted urban management strategies. These findings indicate that large cities play a crucial role in national economic dynamics, suggesting that policymakers should focus on improving infrastructure, education, and innovation in major urban centers to stimulate economic growth. By targeting urban management strategies towards these key areas, policymakers can harness the economic potential of large cities, mitigate the impact of idiosyncratic shocks, and promote sustainable economic development.

However, it is worthwhile to make a comment on the finding of some negative R2 values. In the U.S., negative adjusted R2 values were observed for certain K values (number of largest cities included) at the county level, indicating the weak explanatory power of the hypothesis for these areas. However, U.S. metropolitan areas generally showed positive, significant R2 values, supporting the hypothesis in these regions. Brazilian municipalities presented mixed results. While some K values showed positive R2 values, metropolitan areas did not support the granular hypothesis. No regression for these areas exceeded their population percentages in R2 values, leading to the hypothesis’s rejection.

The negative R2 values in U.S. counties and Brazilian metropolitan areas imply the granular hypothesis’s limitations for these specific analyses. This might be due to the following: (1) Varying levels of economic integration and dynamics across counties, municipalities, and metropolitan areas. Large cities and counties may exhibit unique economic patterns not captured by the hypothesis. (2) Large cities’ distinct economic features and challenges, potentially leading to negative R2 values if these specificities are not accounted for in the model. (3) Possible limitations of the methodology used to test the granular hypothesis, especially in capturing complex economic dynamics at the city level.

The difference in the applicability of the granular hypothesis between Brazilian municipalities and metropolitan areas might be due to the degree of aggregation. As aggregation increases, the granular residual tends to regress to the mean following the law of large numbers. In simpler terms, when calculating the residual for the entire metropolitan area, the impact of the central city’s idiosyncratic shock becomes diluted within the residual. To test the hypothesis, we used OLS regression, with the growth rate of metropolitan areas (excluding the central city) as the variable to be explained and the growth rate of the central city as the explanatory variable. Regression directly on the residual indicates a positive granular effect, given the larger population of the metropolitan area compared to the central city. As anticipated, the coefficient estimated for the growth rate is positive but less than one, showing a positive yet imperfect correlation, supporting regression to the mean. We excluded areas with central cities having less than 100,000 inhabitants on average, reducing observations from 82 to 53. Table 9 confirms that the hypothesis is not rejected. Generally, variations in central cities’ per capita GDP growth rate have limited explanatory power for their periphery’s growth rate (low R2), as the value is as expected, positive and less than one.

Table 9.

Regressing the growth rate of the largest municipalities in the periphery by the growth rate of their respective central cities, 2003–2019.

When calculating the residual solely for other municipalities in the metropolitan areas (excluding central cities), the adjusted R2 significantly reduces, often becoming negative. This indicates that these outskirts contribute minimally to the business cycle and have little to no growth spillover effects on the rest of the country (Table 10). In particular, the outskirts of large central cities are themselves highly populous. For instance, the surroundings of São Paulo account for over 4% of the Brazilian population and, if treated as a single municipality, would be the country’s second-largest.

Table 10.

Regressions with the granular residual of metropolitan area municipalities, excluding the central cities.

In Gabaix (2011)’s methodology, the granular residual is a sum, preserving all data and potentially leading to biases and reduced explanatory power in the metro areas’ granular residual. Consequently, the granular hypothesis is rejected for Brazilian metro areas, unlike large municipalities, which are central cities with a higher proportion of the national population. By adopting multiple regression methodology, we can discard irrelevant data, such as metro areas with a negative marginal effect on the R2/population ratio. For instance, the exclusion of the São Paulo metropolitan area, which weakens the granular residual’s explanatory power, is shown in Table 11, which showcases metro areas where the R2/population ratio consistently exceeds one in all specifications.

Table 11.

Brazilian metropolitan areas’ debiased granular residual.

3.3. Granular Size

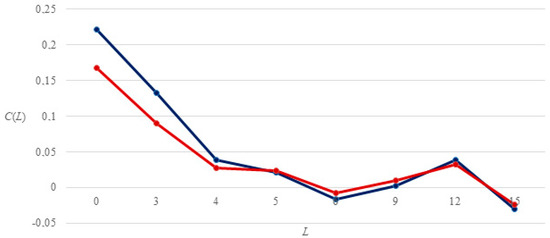

The granular size K* represents the number of largest cities whose economic activities have the most substantial impact on national economic fluctuations, highlighting their critical role in driving the business cycle and informing targeted urban policy interventions. In Figure 1, the granular size for U.S. counties, based on Equation (3), is illustrated. The granular (weighted) curve and equally weighted curve intersect at L = 5, determining the value K* = 5. This refers to Los Angeles, Cook, Harris, Maricopa, and San Diego counties, which represent about 8.4% of the U.S. population on average over the period but account for 48% of the business cycle (Table 5).

Figure 1.

Granular size for the U.S. counties: granular curve (blue) and equal-weight curve (red), 2002–2019.

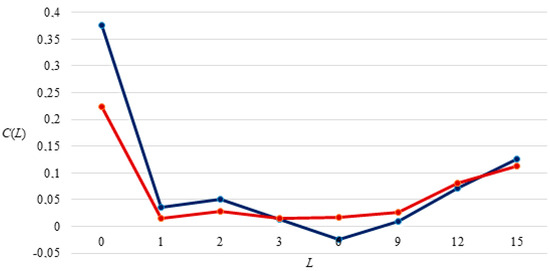

Equation (3) reveals that the granular size for U.S. metropolitan areas occurs at L = 3 (Figure 2). The value K* = 3 corresponds to New York–Northern New Jersey–Long Island, Los Angeles–Long Beach–Santa Ana, and Chicago–Joliet–Naperville. These three metro areas represent around 13.4% of the American population but explain 49% of the business cycle (Table 6). As anticipated, due to higher population density in the largest metropolitan areas compared to counties, the granular size for metro areas is lower.

Figure 2.

Granular size for the U.S. metro areas: granular curve (blue) and equal-weight curve (red), 2002–2019.

The top three metropolitan areas with the most significant granular effect are situated in different geographic regions of the United States. Interestingly, similar to the counties, none of these granular metro areas are capital cities (e.g., Albany, Springfield, and Sacramento). This aligns with the idea that there is a positive correlation between political power and human agglomerations, as proposed by Ades and Glaeser (1994).

New York City, the largest municipality in the U.S., does not have a significant granular effect among counties, but it becomes relevant within the greater metropolitan area. The adjusted R2 drops from nearly 0.4 with L = 0 (considering New York–Northern New Jersey–Long Island) to just below 0.05 with L = 1 (when this metro area is excluded). However, the increased importance of the greater Los Angeles area indicates that the growth of Los Angeles and its surroundings appears to be unrelated to that of the rest of the country.

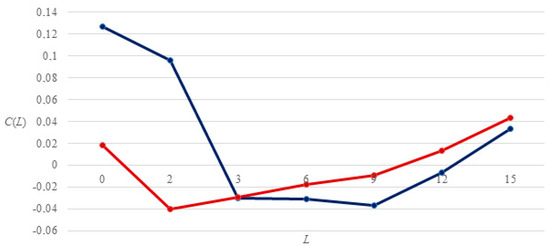

When applying Equation (3) to Brazilian municipalities, the granular and equal-weight curves intersect around L = 3 (Figure 3), implying a granular size K* = 3. This indicates that idiosyncratic shocks in São Paulo, Rio, and Salvador significantly impact the economy due to their higher relative weight. Despite being just three municipalities, they represent 10% of the Brazilian population and explain 12% of the business cycle (Table 7). Notably, São Paulo alone contributes about 6% of the population and 13% of the GDP. When excluding the three largest grains, the average adjusted R2 for K is no longer influenced by assigned weights (relative size in the national population).

Figure 3.

Granular size for Brazilian municipalities: granular curve (blue) and equal-weight curve (red), 2002–2019.

Table 12 displays the R2 for each municipality’s regressions using the granular residual, indicating significant variation in explanatory power. Fortaleza, São Bernardo do Campo, João Pessoa, Uberlândia, Ribeirão Preto, and Sorocaba have relatively high adjusted R2 values. Apart from Fortaleza, these municipalities rank above 20, suggesting that as L increases, their relative weight in the granular residual composition grows, leading to higher explanatory power. This phenomenon applies to the equal-weight curve as well, as municipalities with strong explanatory power enter more regressions with increasing L. However, both the granular and equal-weight curves grow at similar rates, with the equal-weight curve slightly higher. This implies that the relative weights (percentage of the Brazilian population) of these municipalities do not contribute significantly to the granular residual’s increased explanatory power.

Table 12.

Granular residual regressions for individual municipalities.

For Brazilian metropolitan areas, using Equation (2) to calculate K* is not applicable, as discussed earlier. Additionally, after debiasing the sample, determining K* becomes unfeasible, as the debiasing process removes the largest grains. Without population shares, very small areas carry relatively higher weight, skewing the results. The equal-weight curve consistently exceeds the granular curve, mainly due to the high correlation of certain small metropolitan areas with national growth. This makes it impossible to ascertain the granular size, K*, using the current methodology.

The comparison between U.S. and Brazilian data reveals notable differences in granular residuals, highlighting the varying economic dynamics between the two countries. In the U.S., metropolitan areas exhibit high granular residuals, indicating their substantial impact on national economic fluctuations. This can be attributed to their roles as major hubs for finance, technology, and innovation, supported by well-developed infrastructure and diverse economic activities. In Brazil, the granular residuals for municipalities also show significant impact but to a lesser extent compared to their U.S. counterparts. The differences can be attributed to several factors. Economically, Brazilian cities are often more dependent on specific industries, which can make them more vulnerable to sector-specific shocks. Geographically, the distribution of cities and the vast distances between major urban centers in Brazil contribute to regional economic disparities. Policy-related factors, such as the focus on addressing rapid urbanization and infrastructural challenges, also play a crucial role. While programs like the Statute of the City aim to promote sustainable urban development, the implementation and resource allocation can vary, impacting the overall economic stability of these urban areas. Thus, the underlying factors contributing to the granular residuals in the U.S. and Brazil differ. Understanding these differences can help policymakers design targeted interventions that address specific economic, geographical, and policy-related challenges.

In summary, our findings do not disconfirm the granular hypothesis, showing that large cities significantly influence national economic fluctuations. The results consistently show that the economic activities of major urban centers play a crucial role in shaping the business cycle, highlighting the importance of considering city-specific factors in macroeconomic analysis. The findings are consistent with previous studies on granular residuals that emphasize the significant impact of large entities on macroeconomic fluctuations. Our study extends this concept to urban centers, showing that large cities, like major firms, play a crucial role in influencing national economic dynamics. This spatial perspective enriches the existing literature by providing new insights into the economic influence of large urban areas.

4. Discussion

Our findings suggest that the concept of granularity, which has been widely applied to firms, is equally relevant in the context of cities. The significant role played by large cities in the business cycle, as evidenced by our analysis of American and Brazilian cities, highlights the need for a more nuanced understanding of urban economic dynamics. This aligns with the findings of Gabaix (2011) and further extends his granular hypothesis to the urban landscape.

The impact of large cities on economic fluctuations can be attributed to several factors. First, large cities serve as hubs for innovation and economic activity, creating spillover effects that influence the broader economy. This is consistent with the arguments made by Glaeser (2011), who emphasizes the role of cities in fostering human capital and innovation. Our results show that idiosyncratic shocks to these large cities do not average out at the national level, thus influencing the overall business cycle.

Moreover, the distribution of city sizes following Zipf’s law suggests that the economic influence of cities is hierarchical. This is supported by the work of Chauvin et al. (2017), who provide a comprehensive overview of Zipf’s law in urban systems. Our findings indicate that the largest cities, such as São Paulo in Brazil and New York in the United States, play a disproportionate role in national economic performance. This is in line with the observations of Bettencourt et al. (2007), who highlight the scaling properties of cities and their economic output.

In addition, our analysis of the granular residuals shows the importance of considering city-specific characteristics and their integration into the national economy. The significant explanatory power of the granular residual, particularly in the case of large metropolitan areas, suggests that policies aimed at fostering urban growth and innovation can have far-reaching economic benefits. This perspective is supported by the work of Duranton and Puga (2004), who argue that larger cities enhance productivity through knowledge spillovers and labor market pooling.

Furthermore, the implications of our study extend to urban planning as well as policymaking. By understanding the granular effects of large cities, policymakers can design targeted interventions to mitigate economic volatility and promote sustainable growth. For instance, investments in infrastructure and education in major urban centers can amplify their positive spillover effects, as suggested by Florida (2019). Our findings advocate for a strategic approach to urban development that leverages the economic potential of large cities while addressing the challenges they face.

Therefore, this study contributes to the literature by highlighting the spatial dimension of granularity and its implications for the business cycle. Future research could explore the granular effects of cities in other emerging economies and examine the long-term impacts of urbanization on economic stability. Our results emphasize the need for a comprehensive understanding of urban economic dynamics and their critical role in shaping national economic outcomes.

Although the granular size for U.S. counties (K* = 5) is higher than for Brazilian municipalities (K* = 3), the proportion of the population in the U.S. case is lower. This means granular municipalities in Brazil are larger than granular counties in the United States. Even the largest American municipality, New York City, and the largest county, Los Angeles County, only represent approximately 3% of the total U.S. population. In contrast, Sao Paulo accounts for about 6% of the Brazilian population.

The significance of this difference possibly lies in the historical, economic, and social contexts of each country. Historically, the U.S. has experienced more dispersed urban development due to factors such as westward expansion and the development of multiple economic hubs across the country. Economically, the U.S. has a more diversified set of large urban centers, each with its own significant contribution to the national economy. In contrast, Brazil’s urban development has been more centralized. Social factors may also play a role. The concentration of population in fewer large cities in Brazil can lead to more pronounced economic impacts from these urban centers, affecting national economic trends more significantly. This centralization might be driven by the historical colonial focus on coastal cities and later industrialization patterns that concentrated resources and opportunities in a few urban areas.

Zipf’s law, being a statistical phenomenon with no underlying causes (Mandelbrot 1961), could account for random differences between the two countries. However, Ades and Glaeser (1994) present a compelling causal argument linking political factors to urban concentration, not vice versa. They argue that in more authoritarian countries with less economic freedom, the population tends to concentrate around political poles like national or state capitals. This political power concentration also corresponds to income concentration, attracting poorer populations to these large centers and leading to higher overall population concentrations.

Applying this causal narrative to Brazil, we find two granular municipalities in the Southeast, situated 450 km apart. In contrast, only the Northeast lacks granular counties in the United States, possibly due to historical reasons. Economic Freedom Index rankings for 2022 place the United States 25th and Brazil 133rd, suggesting a higher concentration of the Brazilian population near centers of power. Remarkably, all three granular municipalities in Brazil are state capitals, and even a relatively new municipality like Brasília, founded in 1960, already houses about 1.5% of the Brazilian population, surpassing Washington, D.C., established in 1791, which has only around 0.2% of the U.S. population. This points to a higher spatial concentration of economic activity in Brazil compared to the United States, potentially linked to political factors. The granular size serves as a measure of concentration, with fewer grains indicating greater economic importance in a region.

Moreover, the Sun Belt accommodates four out of the five granular counties in the United States, supporting the hypothesis that the warmest U.S. regions in January act as significant population magnets, experiencing faster growth rates than the national economy (Glaeser and Gottlieb 2009). This population analysis also clarifies why U.S. cities have a greater impact on the business cycle than Brazilian cities, considering their relative sizes.

The role of political factors in urban concentration is a crucial aspect of understanding the economic dynamics of large cities. Political centralization in Brazil has historically influenced population concentration in major urban centers. For instance, the colonial administration’s focus on coastal cities like Rio de Janeiro and Salvador established early patterns of urban concentration. Subsequent industrialization and economic policies further reinforced the centrality of cities like São Paulo.

Government policies, including investments in infrastructure and incentives for industrial development, have historically favored these key urban areas (Cano 2007). For example, the establishment of Brasília as the capital in 1960 was a political move intended to decentralize economic activity, yet the economic dominance of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro persisted due to their established industrial bases and infrastructural advantages. Historical data show that significant federal investments were directed towards São Paulo’s industrial sector during the mid-20th century, promoting its growth over other regions (Santos 2017).

The findings align with the previous literature on granular firms (Gabaix 2011). In particular, granular city size is much smaller than firm size, with the largest cities contributing more to the business cycle than the largest companies. For instance, in Brazil, São Paulo accounts for 6% of the population and 13% of the business cycle, while the largest company, Petrobrás, only contributes 4% of the business cycle (Silva and Da Silva 2020). Handling city granularity is akin to dealing with mega-grains. Interestingly, while granular firms in emerging economies have a greater impact on the business cycle (Grigoli et al. 2023), the opposite is true for granular cities. Our results show that large city grains explain a smaller percentage of the business cycle in Brazil (an emerging economy) compared to the United States.

We believe that the impact of granular cities on the business cycle varies between emerging and developed economies due to several factors: (1) Economic activities in emerging economies are often concentrated in a few large firms, significantly affecting the business cycle through their substantial GDP and employment share. In contrast, these activities are more dispersed across cities, reducing their influence on the business cycle compared to developed economies, where cities have more economic concentration. (2) Developed economies have urban economies diversified across multiple industries and advanced services, amplifying large cities’ impact on the national business cycle. Emerging economies, with urban economies centered around fewer sectors or dominated by a single firm, experience less influence from their large cities. (3) Cities in developed economies, better integrated into the global economy with advanced infrastructure, significantly impact the business cycle through trade, finance, and technology. In emerging economies, less integration, both domestically and internationally, limits cities’ influence. (4) Developed economies usually have more stable and effective governance, enhancing cities’ role in the business cycle. In contrast, emerging economies may struggle with less efficient urban governance and infrastructure deficits, limiting their cities’ economic impact. In summary, the differing impacts of cities on the business cycle in emerging versus developed economies may stem from economic diversification, structural urban differences, levels of integration and connectivity, and governance effectiveness.

It is important to distinguish between the impacts of granular cities and granular firms on the business cycle because they influence economic dynamics through different mechanisms. Firms impact the business cycle primarily through their production activities, investment decisions, and employment levels. Large firms, particularly those in key industries, can have a disproportionate effect on economic fluctuations due to their significant contributions to GDP and employment.

In contrast, cities influence the business cycle through a broader set of channels, including their roles as centers of consumption, innovation, and economic policy implementation. Cities aggregate diverse economic activities and facilitate interactions among businesses, consumers, and institutions, which can amplify economic shocks. The infrastructure, services, and policies implemented at the city level also play a crucial role in shaping economic outcomes.

In emerging economies, like Brazil, the influence of granular cities is often more pronounced due to higher urban concentration and less diversified economic activities. Policies and investments tend to focus on a few major urban centers, making these cities critical drivers of national economic performance. In developed economies, like the U.S., while large cities also play a significant role, the economic landscape is more dispersed, with multiple cities and regions contributing to economic stability and growth. Understanding these distinctions helps in designing targeted policies that address the specific economic dynamics of cities and firms, ultimately contributing to more effective macroeconomic management.

Echoing Zipf’s law, Christaller’s central place theory, developed in 1933, explains the size, number, and distribution of urban centers based on their role in providing goods and services to surrounding areas (Christaller 1966). According to Christaller, settlements are organized hierarchically based on the range (maximum distance consumers are willing to travel) and threshold (minimum market area needed to support a service). Larger central places offer a greater variety of high-order goods and services to larger hinterlands, while smaller central places provide lower-order goods and services to smaller areas. Building on Christaller’s work, Lösch introduced modifications in 1940 that added flexibility and realism to the spatial distribution of central places (Lösch 1964). Lösch’s modifications account for transportation costs and the economic landscape, suggesting that central places are not strictly hexagonal but vary based on geographical and economic factors. His model acknowledges real-world deviations, such as natural barriers and varying transportation routes, influencing the spatial organization of central places.

Zipf’s law, which describes the power law distribution of city sizes, complements Christaller’s and Lösch’s theories by emphasizing the heavy-tailed nature of city size distributions. The presence of a few exceptionally large cities alongside numerous smaller ones aligns with the concept of granularity, where idiosyncratic shocks to large cities have significant national economic impacts. This interrelation between granularity and hierarchical urban structures emphasizes the importance of understanding both the spatial and economic dimensions of urbanization. Our study extends the concept of granularity from firms to cities, positing that large cities significantly influence national economic dynamics. This approach aligns with the theoretical foundations laid by Christaller’s central place theory and its modifications by Lösch, which provide a framework for understanding the hierarchical organization of urban centers.

Christaller’s theory suggests that cities function as central places providing goods and services to surrounding regions. This hierarchical structure, determined by the range and threshold of services, leads to a pattern where larger cities offer more diverse and higher-order services to extensive hinterlands. This concept resonates with our findings that large cities play a disproportionate role in the business cycle, serving as hubs of economic activity and innovation. Lösch’s modifications further refine this understanding by considering the economic landscape and transportation costs, which influence the spatial distribution of cities. This perspective explains deviations from the ideal hexagonal pattern in real-world settings, highlighting the importance of geographical and economic factors in shaping urban hierarchies. Our analysis of American and Brazilian cities supports this view, showing that the economic contributions of large cities are influenced by their integration into the national economy and their connectivity within the urban system.

One of the significant challenges in our analysis is the somewhat vague definition of what constitutes a city and where its boundaries lie. This issue is particularly relevant when comparing urban areas in the United States and Brazil, as different methods and criteria are used to define and classify urban areas and metropolitan regions.

In the United States, cities and metropolitan areas are defined based on criteria set by the Census Bureau. Metropolitan Statistical Areas encompass a central city and its economically integrated surrounding areas. The boundaries are determined based on commuting patterns and economic ties, which may include multiple counties. This approach aims to capture the functional economic region centered around a large urban core, but it can lead to variability in how urban areas are delineated across different regions.

In Brazil, urban areas are typically defined as municipalities, which are single administrative units. However, the concept of metropolitan regions (Regiões Metropolitanas) also exists, where a central municipality and its surrounding municipalities are grouped based on economic and social linkages. These metropolitan regions are officially recognized and have specific administrative and planning structures, but the criteria for their boundaries can vary significantly from those in the United States.

The differences in defining and classifying urban areas between the two countries pose challenges in directly comparing their urban hierarchies and the impact of large cities on national economic dynamics. While our study applies a consistent methodology to analyze the granular effects of cities, the underlying definitions and boundaries can influence the results. For instance, the broader and more flexible definition of metropolitan areas in the United States might capture a more extensive economic impact zone compared to the typically smaller and more rigidly defined municipalities in Brazil.

These variations highlight the importance of considering the context-specific definitions of urban areas when interpreting the results. The concept of granularity applied to cities must account for the administrative and functional differences in defining urban regions. Future research should aim to standardize or harmonize these definitions where possible or at least explicitly account for these differences when comparing urban dynamics across different countries.

Understanding the nuances in urban definitions is crucial for policymakers and urban planners. Policies designed to target urban development and economic growth need to be tailored to the specific administrative and functional structures of cities and metropolitan regions. Recognizing these differences can lead to more effective and contextually appropriate interventions that harness the economic potential of large cities and mitigate the challenges associated with urbanization.

While our study emphasizes the significant impact of large cities on national economic dynamics through the lens of granularity, it is crucial to acknowledge the networked and relational nature of modern economies, which also applies to cities. The interconnectivity between cities through trade, migration, information flows, and economic activities creates a complex web of relationships that influence economic outcomes beyond the size of individual cities.

The relational aspect of urban economies suggests that the economic performance of a city cannot be fully understood in isolation. Cities are embedded in a network of interdependencies where economic activities, innovations, and shocks in one city can have ripple effects on others. For instance, the success of tech hubs not only impacts the local economy but also influences innovation and economic activities in other cities globally. This networked nature amplifies the significance of understanding how cities interact with each other and contribute collectively to national and global economic dynamics.

Our analysis, while focused on the size and granularity of cities, could benefit from incorporating these network effects to provide a more comprehensive view of urban economic dynamics. Network analysis techniques, such as examining trade linkages, commuting patterns, and information flows between cities, could offer deeper insights into how interconnected cities influence each other and the broader economy. Understanding these relationships can help identify key nodes in the urban network that play pivotal roles in macroeconomic stability and growth.

Furthermore, the comparison between the United States and Brazil reveals that different methods of defining and classifying urban areas can influence our understanding of urban hierarchies and their economic impacts. In the U.S., Metropolitan Statistical Areas consider economic linkages and commuting patterns, while in Brazil, municipalities and metropolitan regions are defined based on administrative boundaries. These differences highlight the importance of considering the relational and networked aspects of cities, as the definition and classification of urban areas can affect the analysis of their economic contributions.

Therefore, while our study emphasizes the importance of city size and granularity, it is essential to integrate the networked and relational character of urban economies to capture the full spectrum of urban economic dynamics. Future research should explore these network effects and their implications for urban policy and economic planning, recognizing that cities do not function in isolation but as interconnected entities within a broader economic system.

5. Conclusions

Large cities play a crucial role in the business cycle, as they are home to granular firms, which are primarily responsible for driving it. This study explores the concept of granularity, extending it from firms to cities, and investigates how granular cities influence the business cycle. Our contribution is to highlight a spatial component of granularity not considered so far. The analysis is based on data from 2003 to 2019, focusing on cities in the United States and Brazil, where we observe that city size distributions adhere to Zipf’s law. By computing the granular residual, we identify the granular size for these cities.

The granular size for counties in the U.S. is five, representing Los Angeles, Cook, Harris, Maricopa, and San Diego counties. These five counties, comprising 8% of the U.S. population, contribute to 48% of the business cycle. Similarly, the granular size for metropolitan areas is three, including New York–Northern New Jersey–Long Island, Los Angeles–Long Beach–Santa Ana, and Chicago–Joliet–Naperville. These areas, accounting for 13% of the American population, explain 49% of the business cycle. In Brazil, the granular size is three, with municipalities representing 10% of the population and explaining 12% of the business cycle. Therefore, we could not reject the hypothesis that cities in the United States and Brazil explain a greater proportion of the business cycle than their relative size.

Conventional analyses of the business cycle focus on national or regional levels, but examining it at the city level offers deeper insights into local economic dynamics. This approach holds practical value for policymakers, urban planners, and businesses. The discovery that cities wield significant influence on the business cycle, beyond their size, has vital implications. It allows us to pinpoint cities’ economic strengths and weaknesses, facilitating targeted policies for growth and resilience. Moreover, it aids in assessing regional imbalances, enabling more effective resource allocation to address disparities and promote balanced development.

The results of our study carry significant implications for urban policy and macroeconomic policymaking. The prominent role of large cities in driving national business cycles suggests that targeted policy interventions in these urban centers can have far-reaching effects. Policymakers should consider the unique characteristics and economic contributions of these cities when designing economic policies. First, investments in infrastructure within large cities can enhance their role as economic hubs. Improved transportation networks, digital infrastructure, and public services can boost productivity and innovation, leading to positive spillover effects on smaller cities and the broader economy. Second, policies aimed at promoting human capital development in large cities can yield substantial economic benefits. Education and training programs tailored to the needs of these urban centers can equip the workforce with the skills required for high-growth industries. As the discussed literature suggests, cities that invest in education and attract skilled labor tend to experience higher levels of innovation and economic dynamism. Therefore, policymakers should prioritize educational initiatives and workforce development programs in large cities to sustain long-term economic growth. Moreover, fostering innovation through support for research and development activities in major urban centers can amplify their economic impact. Establishing innovation districts and providing incentives for startups and tech companies can create vibrant ecosystems that drive technological advancements. In addition, addressing the challenges faced by large cities, such as housing affordability and environmental sustainability, is crucial for maintaining their economic vitality. Policies that promote affordable housing development and sustainable urban planning can mitigate the negative externalities associated with rapid urbanization. Balancing economic growth with quality-of-life improvements is essential for the sustainable development of large cities. Lastly, there is a need for a coordinated approach to urban policy that considers the interdependencies between large and small cities. National and regional governments should collaborate to design policies that leverage the strengths of large cities while addressing the needs of smaller urban areas. This can include strategies for regional development, equitable resource allocation, and integrated economic planning to ensure balanced and inclusive growth across the urban hierarchy. In conclusion, the granular effects of large cities on the business cycle emphasize the importance of tailored policy interventions that enhance the economic potential of these urban centers. By investing in infrastructure, education, innovation, and sustainable development, policymakers can harness the economic power of large cities to drive national prosperity and resilience.