The Mechanism of an Individual’s Internal Process of Work Engagement, Active Learning and Adaptive Performance

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Self-Efficacy and Work Engagement

2.2. Growth Mindset and Work Engagement

2.3. Work Engagement and Active Learning

2.4. Work Engagement and Individual Adaptive Performance

2.5. Active Learning and Individual Adaptive Performance

3. Methods

4. Results

4.1. Survey Result

4.2. Interview Result

4.2.1. The Mechanism between an Individual’s Internal Processes, Work Engagement, and Active Learning

4.2.2. The Mechanism between Work Engagement, Active Learning, and Adaptive Performance

4.3. Triangulation of the Findings

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Significant Example Quotes | Coding | Themes |

|---|---|---|

| “Individuals growth mindset are very needed in our company to face the rapid advancement of digital technology. The growth mindset leads people who are enthusiastic and willing to work more with dynamic job demands and constantly changing knowledge” | Growth Mindset leads individuals to have high self-initiative and enthusiasm regarding their job demand or market (dedication) | The Mechanism between Growth-Mindset and Work Engagement |

| “Individuals with a growth mindset tend to have more open to knowledge and change based on the dynamic market/tech advancement. This encourages them to work more and seek solutions for new job demands or new opportunities in the market” | Growth Mindset leads individuals to be resilient to change and stay engaged with their job even though the job demand is high (vigor) | |

| “This growth mindset is very necessary because our product requires individuals to continue to learn new knowledge or skills, so from that, they will immediately explore in-depth even outside their working hours to be able to complete the new job demand” | Growth Mindset leads individuals to explore new knowledge or skills even though it takes more energy and time out from their working time (absorption) | |

| “When they have high confidence in their own capabilities, they will want to work more even with new jobs or challenges at work” | Self-Efficacy enhances individuals’ work effort (dedication) | The Mechanism between Self-Efficacy and Work Engagement |

| “This sense of belief in one’s own capabilities will give confidence that can boost new innovative ideas. This makes employees enjoy it more and more deeply to explore their work” | Self-Efficacy allows individuals to easily initiate new ideas through their confidence (absorption) | |

| “Self-Efficacy is very influential in doing exploration in their production process. This individual belief gives more strength to their mentality to face changes or new challenges in the workplace” | Self-Efficacy provides more mental energy to deal with split work (vigor) | |

| “When he (employee) is engaged with his work, he will willingly learn and commit new knowledge related to product features or product development process. But if they are not, they will just know the information but no new knowledge” | Work engagement’s vigor behavior drives individuals to learn more and absorb new knowledge effectively through active learning | The Mechanism between Work Engagement and Active Learning |

| “Employees who are engaged with their work tend to be responsible and explore and reflect deeply on new knowledge so that they can find new innovative ideas for products” | Absorption allows individuals to explore and learn independently, reflect on their new knowledge and build new ideas | |

| “Employees who are engaged with their work will be enthusiastic and willing to work longer at the desk. It directs them to share knowledge with colleagues from other divisions and combine different perspectives and knowledge into one new product innovation idea” | Dedication toward their work allows individuals to have effective knowledge sharing in building new innovative ideas in products resulting from the knowledge combination process | |

| “Individuals who want to take the initiative to learn the latest new things will have new knowledge that comes from new digital technology advancements, various perspectives from their colleagues or customers. This makes him more creative in building ideas in solving new challenges or problems in the workplace” | Self-Initiative in learning and mastery of new knowledge leads individuals to solve problems more creatively | The Mechanism between Active Learning and Adaptive Performance |

| “In our place, people who are actively learning tend to have no problem with changes from clients or superiors, and when there are changes, they will have more creative problem solving than their learning process” | Individuals who have active learning tend to be open to change and capable of solving emergencies effectively | |

| “Our employees who are actively learning are used to managing their time and energy well, so they can also easily manage the existing work stress” | Individuals who like to develop themselves and actively learn tend to be able to manage work stress well | |

| “Basically, the production process in our company consists of combining several ideas or knowledge from different divisions, so employees who are actively learning will usually be active in exploring knowledge from their colleagues. So, usually, he does have a good enough training effort and interpersonal skills” | Individuals who have active learning will actively seek new knowledge from their colleagues so that they will have good interpersonal skills and high training effort | |

| “My employees who are engaged with their work are usually easy to adapt to new knowledge or changing client requests. Even so, they can still be enthusiastic, like and explore deeply so that they can perform well” | Individuals who are engaged had a better adaptive mechanism | The Mechanism between Work Engagement and Adaptive Performance |

References

- Acharya, Anita Shankar, Anupam Prakash, Pikee Saxena, and Aruna Nigam. 2013. Sampling: Why and how of it. Indian Journal of Medical Specialties 4: 330–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baard, Samantha K., Tara A. Rench, and Steeve W. J. Kozlowski. 2014. Performance adaptation: A theoretical integration and review. Journal of Management 40: 48–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babeľová, Zdenka Gyurak, and Augustin Stareček. 2021. Evaluation of industrial enterprises’ performance by different generations of employees. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues 9: 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babeľová, Zdenka Gyurak, Marta Kučerová, and Maria Homokyová. 2015. Enterprise performance and workforce performance measurements in industrial enterprises in Slovakia. Procedia Economics and Finance 34: 376–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäckström, Izabelle, and Lars Bengtsson. 2019. A mapping study of employee innovation: Proposing a research agenda. European Journal of Innovation Management 22: 468–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., and Despoina Xanthopoulou. 2013. Creativity and charisma among female leaders: The role of resources and work engagement. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 24: 2760–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., and Evangelia Demerouti. 2007. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology 22: 309–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakker, Arnold B., Evangelia Demerouti, Toon W. Taris, Wilmar B. Schaufeli, and Paul J. Schreurs. 2003. A multigroup analysis of the job demands-resources model in four home care organizations. International Journal of Stress Management 10: 16–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., Evangelia Demerouti, and L. ten Brummelhuis Lieke. 2012. Work engagement, performance, and active learning: The role of conscientiousness. Journal of Vocational Behavior 80: 555–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, Arnold B., and Jessica van Wingerden. 2021. Do personal resources and strengths use increase work engagement? The effects of a training intervention. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 26: 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 2006. Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents 5: 307–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, Albert. 2012. On the functional properties of perceived self-efficacy revisited. Journal of Management 38: 9–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bell, Bradford S., and Steve W. J. Kozlowski. 2008. Active learning: Effects of core training design elements on self-regulatory processes, learning, and adaptability. Journal of Applied Psychology 93: 296–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boeker, Warren, Michael D. Howard, Sandip Basu, and Arvin Sahaym. 2021. Interpersonal relationships, digital technologies, and innovation in entrepreneurial ventures. Journal of Business Research 125: 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesens, Gaetane, and Florence Stinglhamber. 2014. The relationship between perceived organizational support and work engagement: The role of self-efficacy and its outcomes. European Review of Applied Psychology 64: 259–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangur, Sengul, and Ilker Ercan. 2015. Comparison of model fit indices used in structural equation modeling under multivariate normality. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods 14: 152–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniëls, Marjolein C. J., Judith H. Semeijn, and Irma H. M. Renders. 2018. Mind the mindset! The interaction of proactive personality, transformational leadership and growth mindset for engagement at work. Career Development International 23: 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Charbonnier-Voirin, Audrey, and Patrice Roussel. 2012. Adaptive performance: A new scale to measure individual performance in organizations. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l’Administration 29: 280–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, Michael S., Adela S. Garza, and Jerel E. Slaughter. 2011. Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Personnel Psychology 64: 89–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Spiegelaere, Stan, Guy Van Gyes, Hans De Witte, and Geert Van Hootegem. 2015. Job design, work engagement and innovative work behavior: A multi-level study on Karasek’s learning hypothesis. Management Revue 26: 123–37. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24570254 (accessed on 10 April 2022). [CrossRef]

- Del Libano, Mario, Susana Llorens, Marisa Salanova, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2012. About the bright and dark sides of self-efficacy: Work engagement and workaholism. The Spanish Journal of Psychology 15: 688–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Demerouti, Evangelia, Russell Cropanzano, Arnold B. Bakker, and Michael P. Leiter. 2010. From thought to action: Employee work engagement and job performance. In Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research. East Sussex: Psychology Press, vol. 65, pp. 147–63. [Google Scholar]

- Dezi, Luca, Alberto Ferraris, Armando Papa, and Demetris Vrontis. 2019. The role of external embeddedness and knowledge management as antecedents of ambidexterity and performances in Italian SMEs. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 68: 360–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vaio, Assunta, Rosa Palladino, Alberto Pezzi, and David E. Kalisz. 2021. The role of digital innovation in knowledge management systems: A systematic literature review. Journal of Business Research 123: 220–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, Carol S. 2006. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Fielding, Nigel G., and Jane L. Fielding. 1986. Linking Qualitative Data. Linking Data: The Articulation of Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Social Research. Beverly Hills: Sage, pp. 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and Statistics. Journal of Marketing Research 18: 382–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, Barbara L., and Marcial F. Losada. 2005. Positive affect and the complex dynamics of human flourishing. American Psychologist 60: 678–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frese, M. 2008. The changing nature of work. In An Introduction to Work and Organizational Psychology. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 397–413. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, Joseph F., William C. Black, Bill Black, Barry J. Babin, and Rolph E. Anderson. 2010. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed. New Jersey: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Hakanen, Jari J., and Gert Roodt. 2010. Using the job demands-resources model to predict engagement: Analysing a conceptual model. In Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research. East Sussex: Psychology Press, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Halbesleben, Jonathon R. B. 2010. A meta-analysis of work engagement: Relationships with burnout, demands, resources, and consequences. In Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research. East Sussex: Psychology Press, vol. 8, pp. 102–17. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Soo Jeoung, and Vicki Stieha. 2020. Growth mindset for human resource development: A scoping review of the literature with recommended interventions. Human Resource Development Review 19: 309–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, Stevan E., Jonathon Halbesleben, Jean-Pierre Neveu, and Mina Westman. 2018. Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 5: 103–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keating, Lauren A., and Peter A. Heslin. 2015. The potential role of mindsets in unleashing employee engagement. Human Resource Management Review 25: 329–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, Nina, and Christian Wolff. 2014. Encouraging active learning. In The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of the Psychology of Training, Development, and Performance Improvement. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., pp. 92–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, Caroline, Maria Tims, Jason Gawke, and Sharon K. Parker. 2021. When do job crafting interventions work? The moderating roles of workload, intervention intensity, and participation. Journal of Vocational Behavior 124: 103522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, Rajiv, and Nigel P. Melville. 2019. Digital innovation: A review and synthesis. Information Systems Journal 29: 200–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koyuncu, Mustafa, Ronald J. Burke, and Lisa Fiksenbaum. 2006. Work engagement among women managers and professionals in a Turkish bank: Potential antecedents and consequences. Equal Opportunities International 25: 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupșa, Daria, Delia Vîrga, Laurentiu P. Maricuțoiu, and Andrei Rusu. 2020. Increasing psychological capital: A pre-registered meta-analysis of controlled interventions. Applied Psychology 69: 1506–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melão, Nuno, and Joao Reis. 2020. Selecting talent using social networks: A mixed-methods study. Heliyon 6: e03723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunfam, Victor Fannam. 2021. Mixed methods study into social impacts of work-related heat stress on Ghanaian mining workers: A pragmatic research approach. Heliyon 7: e06918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oevermann, Ulrich. 1979. Sozialisationstheorie. In Deutsche Soziologie Seit 1945. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, pp. 143–68. [Google Scholar]

- Oreg, Shaul, Maria Vakola, and Achilles Armenakis. 2011. Change recipients’ reactions to organizational change: A 60-year review of quantitative studies. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 47: 461–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Yoonhee, Doo Hun Lim, Woocheol Kim, and Hana Kang. 2020. Organizational support and adaptive performance: The revolving structural relationships between job crafting, work engagement, and adaptive performance. Sustainability 12: 4872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richels, Kelsey A., Eric Aanthony Day, Ashley G. Jorgensen, and Jonathan T. Huck. 2020. Keeping calm and carrying on: Relating affect spin and pulse to complex skill acquisition and adaptive performance. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, Christian, Dirceau da Silva, and Diogenes Bido. 2015. Structural equation modeling with the SmartPLS. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2676422 (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B., and Arnold B. Bakker. 2004. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior 25: 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schaufeli, Wilmar B., Arnold B. Bakker, and Marisa Salanova. 2006. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement 66: 701–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmering, Marcia J., Jason A. Colquitt, Raymond A. Noe, and Christopher O. L. H. Porter. 2003. Conscientiousness, autonomy fit, and development: A longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Psychology 88: 954–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taris, Toon W., and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2015. The job demands-resources model. In The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of the Psychology of Occupational Safety and Workplace Health. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., pp. 155–80. [Google Scholar]

- Taris, Toon W., Michiel A. J. Kompier, Annet H. De Lange, Wilmar B. Schaufeli, and Paul J. G. Schreurs. 2003. Learning new behaviour patterns: A longitudinal test of Karasek’s active learning hypothesis among Dutch teachers. Work & Stress 17: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortora, Debora, Roberto Chierici, Massimiliano Farina Briamonte, and Riccardo Tiscini. 2021. ‘I digitize so I exist’. Searching for critical capabilities affecting firms’ digital innovation. Journal of Business Research 129: 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakola, Maria. 2013. Multilevel readiness to organizational change: A conceptual approach. Journal of Change Management 13: 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Heuvel, Matchteld, Evangelia Demerouti, Arnold B. Bakker, Jorn Hetland, and Wilmar B. Schaufeli. 2020. How do employees adapt to organizational change? The role of meaning-making and work engagement. The Spanish Journal of Psychology 23: e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Wingerden, Jessica, Arnold B. Bakker, and Daantje Derks. 2017. Fostering employee well-being via a job crafting intervention. Journal of Vocational Behavior 100: 164–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Woerkom, Marianne, Arnold B. Bakker, and Lisa H. Nishii. 2016. Accumulative job demands and support for strength use: Fine-tuning the job demands-resources model using conservation of resources theory. Journal of Applied Psychology 101: 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yvonne Feilzer, Martina. 2010. Doing mixed methods research pragmatically: Implications for the rediscovery of pragmatism as a research paradigm. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 4: 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Suli, Wei Zhang, and Jian Du. 2011. Knowledge-based dynamic capabilities and innovation in networked environments. Journal of Knowledge Management 15: 1035–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

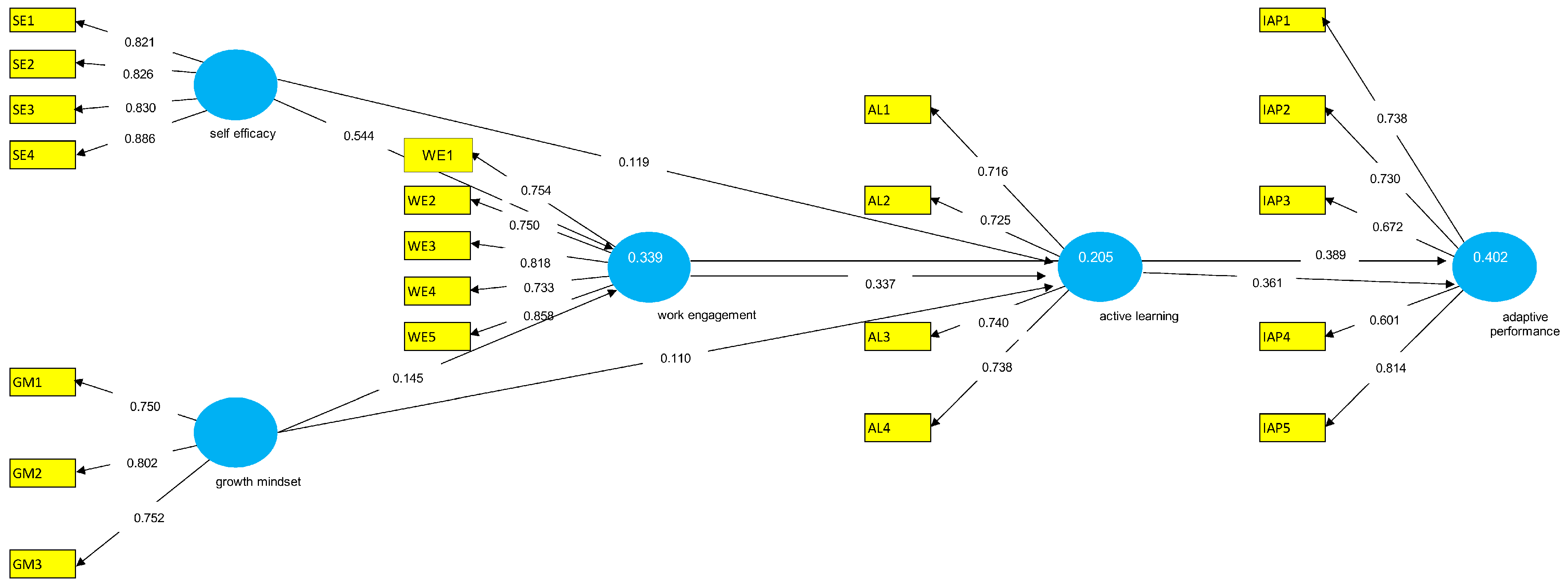

| Construct | Items | Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active Learning | AL1 | 0.716 | |

| AL2 | 0.725 | ||

| AL3 | 0.740 | ||

| AL4 | 0.738 | 0.708 | |

| Work Engagement | WE1 | 0.754 | |

| WE2 | 0.750 | ||

| WE3 | 0.818 | ||

| WE4 | 0.733 | ||

| WE5 | 0.858 | 0.841 | |

| Individual Adaptive Performance | IAP1 | 0.738 | |

| IAP2 | 0.730 | ||

| IAP3 | 0.672 | ||

| IAP4 | 0.601 | ||

| IAP5 | 0.804 | 0.758 | |

| Self-Efficacy | SE1 | 0.823 | |

| SE2 | 0.823 | ||

| SE3 | 0.828 | ||

| SE4 | 0.887 | 0.862 | |

| Growth Mindset | GM1 | 0.750 | |

| GM2 | 0.802 | ||

| GM3 | 0.752 | 0.657 |

| Relationships | Beta | S.D. | T-Stat | p-Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Efficacy → Work Engagement | 0.537 | 0.066 | 8.083 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Growth Mindset → Work Engagement | 0.183 | 0.064 | 2.838 | 0.005 | Supported |

| Work Engagement → Active Learning | 0.418 | 0.074 | 5.549 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Self-Efficacy → Active Learning | 0.058 | 0.074 | 0.791 | 0.429 | Not Supported |

| Growth Mindset → Active Learning | 0.097 | 0.069 | 1.416 | 0.157 | Not Supported |

| Work Engagement → Adaptive Performance | 0.367 | 0.064 | 5.759 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Active Learning → Adaptive Performance | 0.454 | 0.060 | 7.624 | 0.000 | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nandini, W.; Gustomo, A.; Sushandoyo, D. The Mechanism of an Individual’s Internal Process of Work Engagement, Active Learning and Adaptive Performance. Economies 2022, 10, 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10070165

Nandini W, Gustomo A, Sushandoyo D. The Mechanism of an Individual’s Internal Process of Work Engagement, Active Learning and Adaptive Performance. Economies. 2022; 10(7):165. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10070165

Chicago/Turabian StyleNandini, Widya, Aurik Gustomo, and Dedy Sushandoyo. 2022. "The Mechanism of an Individual’s Internal Process of Work Engagement, Active Learning and Adaptive Performance" Economies 10, no. 7: 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10070165

APA StyleNandini, W., Gustomo, A., & Sushandoyo, D. (2022). The Mechanism of an Individual’s Internal Process of Work Engagement, Active Learning and Adaptive Performance. Economies, 10(7), 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10070165