Abstract

Business bribery is a particularly serious problem in the integration era. First, this article investigates the effects of institutional obstacles on firms’ bribery in 131 countries classified by nation income groups. Through the appropriate proposal of fitting functions, the relationship between obstructions and the predicted margin effect of bribery is intuitively elucidated. Second, this paper sheds light on the relationship between bribery payment and exports. Then the analysis is upgraded when controlling for the moderation of a firm’s growth constraints. The results detected that not only institutional barriers, but also internal and external hindrances play an essential role in the interaction between bribe payments and export share. More interestingly, this study scrutinizes the role of obstacles in this relationship separately. Besides, SMEs and large enterprises are also adopted in further sensitivity analyses. To solve the endogeneity problem, the study uses the average amount of bribery in a firm’s location, sector, and the country as an instrumental variable (IV). The results obtained are not consistent across country groups classified by national income. Due to obstacles during a firm’s operation, the amplitude of the positive effect of bribery on exports is reduced.

1. Introduction

Bribery is a global problem and exists in all areas of economics, society, and politics. No country in the world is immune from corruption. Bribery can take many forms, such as bribing officials to secure contracts, or lobbying and kickbacks aimed at distorting institutional activities. This behavior can create inequality in society, and cost the economy. Thus, addressing all of them is crucial to achieving sustainable progress and change. One reason behind the increase in bribery is participation in international marketsOne reason behind increasing bribery is the reliance on international trade integration.

Petrou and Thanos (2014). Therefore, the bribery situation in developing countries and transition economies is more complicated than in developed countries Olken and Pande (2012). Nevertheless, business bribery appears most often, hidden behind various guises Luo (2005). This activity aims to benefit the firm by smoothing administrative procedures, receiving preferential treatment, avoiding inspections, and audits, etc. As a result many previous empirical studies revealed that this behavior has a significant effect on firms’ performance, for instance, on business strategy Spencer and Gomez (2011), innovation Xie et al. (2019); Krammer (2019), competitiveness Beck and Maher (1989), and export activity Gao et al. (2010).

Integration is becoming an indispensable trend throughout economies in the world, especially in developing countries. Developing exports according to a sustainable and reasonable growth model is seen as a solution to open the economy to take advantage of foreign capital and technology of developing countries. The effects of exports, however, depend on the characteristics of the national economic system. In some cases, as shown, for example by Gros (2013) and by Lucarelli et al. (2018), in the case of EMU countries, they can destabilize the macroeconomy. Therefore, research on factors that affect the export of firms is an interesting topic and has practical value. This topic not only attracts the interest of macroeconomic managers but also receives the attention of business managers.

Nonetheless, the firm’s decision-making is a harmonious combination of many complex factors and characteristics Coase (1937). For example, Hellman and Schankerman (2000) suggested that small firms are more likely to be asked for bribes and pay higher informal fees than large ones. Because they are less able to negotiate and meet official requests. Corruption and solicitation of bribes arise from poor social governance Rose-Ackerman (2005). Institutional gaps caused by cumbersome regulations, unstable democratic politics and overlapping management methods, etc., create opportunities for harassment for certain individuals and sectors in the economy. In addition, barriers in the growth process of enterprises include internal difficulties (such as regarding labor, management, financial, etc.), and external obstacles (such as unfair competition, the increase of competitors, etc.) are also factors affecting the bribery behavior as well as the exportability of enterprises Svensson (2003). One of the most recent theoretical studies is Cariolle’s paper Cariolle and Sekeris (2021), which proposes a theory explaining the export boom mechanism and promoting bribery. Her research paid attention to the reaction of exporters concerning bribery when there is a boom or bust in the export market. One conclusion of the study found that firms would use bribery to increase their market value. However, the variability of exports and bribery depends not only on the export market size but also on the firm’s level of human capital. If enterprises have low human capital, they will seek to increase bribery to expand the market. Then, a positive export shock will reduce the bribery balance. By contrast, if the enterprise has a high level of human capital, the export market value, and a large export market size, the enterprise still tends to bribe a lot to gain market share. A positive export shock will reduce the bribe balance when there is weak revenue complementarity between market value and output. As an effect, the interaction between export and bribery needs to be considered in terms of the moderation of firm’s growth obstacles such as institutions, internal, and external barriers.

Recognizing the importance of exports as well as bribery in enterprises, this study focuses on addressing research questions as follows: (1) How do a firm’s growth obstacles affect a firm’s bribery payment? (2) How do a firm’s bribery payments affect exporting under the operation obstacles? (3) How do obstacles moderate the relationship between bribery and export?

To solve these questions, the study uses the cross-country data of the World Bank to focus on two primary analyses: (i) investigate the correlation between a firm’s growth obstacles and bribery payments; (ii) estimates a relationship between bribery and a firm’s activities, particularly export activities. Subsequently, by controlling for additional moderating variables, the study demonstrates the interaction of barriers with the influence of bribe payments on a firm’s export. The instrumental variable (IV) approach is applied to address endogenous problems. Moreover, since the model variables are binary and proportional, the models are estimated by Probit regression with instrumental variabe (IV-Probit regression).

While some empirical studies found a positive effect of corruption on a firm’s output and labor capacity in Indonesia (an Asian country) Mendoza et al. (2015); Vial and Hanoteau (2010), some experts found the opposite effect in African factories Mcarthur and Teal (2002); Fisman and Svensso (2007). These conclusions imply that the “greasing” or “sanding” of the wheels depends on exogenous factors such as country characteristics (for example national corruption rate CPI, gross domestic product (GDP)). Therefore, by classifying data groups according to several different criteria such as country income, the export status of firms, and firm size, this study contributes empirical results to the literature on the linkage between export and bribery. The study provides cross-group comparisons to highlight the extent of bribery and barriers on firms’ exports under specific conditions of firm and country characteristics. These results can have many implications for policy makers and business managers. Besides, the study performs further analysis by adopting different clusters by firm size.

2. Literature Review

This section reviews some typical modeling and optimization work to understand and collect necessary experiences for the coming steps.

2.1. Review of Theoretical Models

Rose-Ackerman (1975) was a pioneer in research on the “economy of corruption”. Rose’s corruption model showed a link between market structure and bribery, with a focus on policy elements that prevent corruption. She stated that bribery is quite common in the private sector. Based on the Rose’s model, Svensson (2003) found evidence of a positive relationship between bribery rates and the authorities’ control over firms’ activities. This result implied that obstacles in a firm’s operations increase its likelihood and the cost of bribery. Besides, he pointed out the probability that firms offer bribes. Enterprises with a high bribery potential are the ones with more activities involving the authorities because this creates more opportunities for harassment, such as firms engaged in import and export, investment loans, restructuring, etc. Furthermore, their study discussed an interesting and rather important conclusion that officials solicit bribes based on the firm’s ability to pay. In other words, the firm’s characteristics such as current profit, expected profit, etc. will affect the amount of bribe. However, in contrast, each enterprise can only pay bribes to a limited extent depending on its characteristics.

A common approach to bribery is the queuing theory supported by Cobham (1954); Wishart (1960); Kleinrock (1967); Lui (1985). This theory assumed that bribery depends on the customer’s ability to pay and the satisfaction level. In particular, the client’s bribe amount depends on their ability to pay, expected position in the queue, and their taste for waiting. These findings showed that customer waiting time costs appear to fall with average bribery rates. However, as bribes increase, some weights in the bribery function model will change, causing this cost to grow again, although the rate of increase is slower than the initial decrease rate.

Unlike previous bribery models often referred to as static models, Wu and Lan (2018) built dynamic models of firm-level bribery decisions to determine their bribe’s size and optimize its future value. The author considered the firm’s status concerning bribery in the last term. Additionally, Wu examined the role of infrastructure obstacles in the bribery-production nexus. Moreover, in Wu’s study, bribery is intended to lubricate the business wheels either actively or passively. Therefore, bribery is seen as a business strategy and not audited like bribing government officials. In other words, the author ignored the illegality of bribery. One exciting point is that he built a firm-level model to explain the bribery decisions of firms and developed aggregate-level analysis for many firms in industries. Additionally, Wu provided suggestions for applying the bribery control policy after analyzing decision-making processes at both the firm and industry levels. Accordingly, a strategy that increases the cost of bribery, such as strictly monitoring firms’ financial activities or eliminating the post-bribery benefits, can be applied, such as removing lower infrastructure impediments obtained by paying bribes. According to the author, both of these policies can successfully reduce the number of companies engaging in bribery by 50%.

Furthermore, there are also other notable theoretical frameworks for bribery. For example, the equilibrium model that built on the social balance between the agencies’ effort to optimize the bribe’s revenue and the goal of optimizing a firm’s profit Henderson and Kuncoro (2004); Kaufmann and Wei (1999); the games theory analysis Henderson and Kuncoro (2004); Macrae (1982); the bargaining model between bribe givers and public servants Ryvkin and Serra (2012); and a principal-agent model Groenendijk (1997).

Applying background models, the collection of empirical studies on bribery is vibrant. Within the study’s limits, the next section of literature presents bribery concerning commerce.

2.2. Review of Empirical Studies: “Greasing the Wheels” versus “Sanding the Wheels”

The empirical literature on bribery shows that its impact on economic performance and firm performance is inconsistent. A series of documents indicate that bribes to state officials can help “greasing the wheels” of commerce without undermining the competitiveness of businesses. Meanwhile, many scholars believe that corruption harms firms, as “sanding the wheels”, ultimately to the detriment of economic development. Consequently, two empirical research groups show conflicting evidence on bribery effects as follows:

Many researchers found shreds of evidence showing that bribe payments bring enterprises certain advantages. Proponents of “corruption is effective” believe that bribery is an incentive for firms to overcome regulation and conduct business more efficiently Leff (1964); Huntingtion (1970). Because bribery encourages authorities to speed up licensing, shorten waiting times for government services, and improve public services’ quality Kleinrock (1967); Lui (1985). Simultaneously, bribery created competition among government officials, leading to a significant improvement in the quality of governance Leff (1964). To support this view, Mendoza’s survey of over 2000 SMEs in 30 Philippine cities found evidence that bribery helps companies “smooth” their operations effectively. In particular, the author found no clues about the growth inhibition or performance reductions of firms caused by bribery. Furthermore, several studies using data from high-corruption countries showed that bribery facilitates enterprises to overcome institutional barriers, ineffective public services and improves firm performance Hellman and Schankerman (2000); Dreher and Gassebner (2013). Furthermore, bribery allows them to access valuable business opportunities and enjoy preferential treatment by building relationships with the government Gamage (2019). As a result, firms increase their ability to participate in the international market as their position in this market is increasingly enhanced Meon and Weill (2008).

Additionally, empirical results in Chinese firms showed that policy uncertainty significantly affects bribery as a driver of corporate product innovation Xie et al. (2019). Research results found a positive relationship between innovation and bribery, supporting the view that bribery payments enable firms to overcome administrative obstacles in emerging countries Krammer (2019). A first-of-its-kind study on the interaction between corruption and product innovation by firms in Vietnam confirmed wheel lubrication. Nguyen et al. (2016) explained that innovation can be seen as a short-term transaction to introduce a product in Vietnamese SMEs. Thus, informal payments (as a bribe) can be effective in these transactions and reduce these processes’ risks and difficulties. These results were similar to those of Krastanova (2014). He claimed that Bulgarian companies also receive significant and positive effects from bribery in their innovation activities. Nevertheless, Mahagaonkar’s research Mahagaonkar (2009) has obtained exciting results on the relationship between corruption and innovation in African countries. This research revealed that both exist simultaneously “greasing the wheels” and “sanding the wheels” when the author categorized innovation into four distinct categories: process, product, organization, and marketing. The obtained results indicated that bribery has only positive effects on marketing innovation and an adverse impact on organizational and product innovation. In addition, the author found no evidence that bribery affects process innovation.

Shleifer and Vishny (1993) also acknowledged that innovation improves when firms engage in bribery, and yet an enterprise that does bribe is easily distrusted. For this reason, Shleifer suspected that these positive numbers are the result of fraud at the bribery firms. These firms dishonestly reported on the state of innovation of their firm.

Thanh et al. (2021) found a positive relationship between bribery and exports. Exporters tend to spend more on bribes. This state exists because the export market carries more risks and requires more standard requirements than the domestic market. Moreover, entering the export market requires enterprises with high enough labor productivity that can bear the export sunk costs Bernard et al. (1995); Aw et al. (2000).

On the other hand, exploring a second aspect of the matter, many empirical publications have proven that bribery aggravates and inhibits the development of enterprises in many regards. Firstly, bribery makes firms tend to increasingly rely on illegal actions to gain benefits, instead of focusing on improving production quality and productivity. Thus, increased bribery leads to a decrease in average labor productivity over time De Rosa et al. (2010); Dal Bo and Rossi (2007). Supporting this idea, Campos et al. (2010) believed that bribery firms tend to offer bribes more seriously in the future because the probability of continuing to make a bribe in the next period is substantial, with increasing size. Additionally, bribery is also a solid barrier to new entrants Birhanu et al. (2016).

Secondly, bribery increases the production and financial costs of enterprises Kaufmann and Wei (1999); Wu and Lan (2018). As a consequence, it reduces the profit from business activities and consequently reduces financial resources’ investment and market expansion capacity Birhanu et al. (2016). Investment growth by firms tends to decrease as bribe payments increase, especially in transition economies Asiedu and Freema (2009). In addition, bribery puts pressure on firm’s innovation Ayyagari et al. (2014). In particular, he studied 25,000 companies in 57 countries and found that those with product innovation had 0.37 higher bribe costs than those that did not. Then, Goedhuys et al. (2016) also found similar results for firms in Egypt and Tunisia. Additionally, a recent study based on Vietnamese SMEs’ 2015 data also supports the hypothesis that firms using bribes as a business strategy will reduce motivation and hinder innovation in a company Nguyen (2020b).

Thirdly, bribery might bring some short-term advantages such as helping firms to pass product quality checking or to break the standard rule about product safety, etc., are also pointed to in other papers Gamage (2019); Svensson (2003); Meon and Weill (2008). As an effect, firms can sell goods of inferior quality or sell goods earlier than competitors. Albeit with short advantages, bribery causes losses for the goods market, consumers, and firms in the long term, such as loss of reputation, loyal customers, and long-term profits Nguyen et al. (2016); Rand and Tarp (2012).

Furthermore, bribery did not have the expected effects on some other firms’ activities. Wellalage et al. (2020) illustrated that bribery SMEs in India face 68% higher credit constraints than non-bribery counterparts. At the same time, a firm that engages in bribery increases the likelihood of its credit constraints by more than 30%. Seker and Yang (2012); Nguyen (2020a) demonstrated that bribery can affect the revenue growth of firms regarding different firm sizes. The revenue of bribery firms tended to be 0.12 points lower than that of non-bribery firms. In addition, by classifying the purpose of bribery, Nguyen found a critical conclusion that some bribery for one purpose may be more beneficial than another. However, no evidence was found that targeted bribery makes a difference in labor productivity. In other words, overall, the net impact of bribery on firms is still negative.

Last but not at least, some “greasing the wheels” scientists argued that a firm’s solid and favorable position in the domestic market creates little incentive to encourage exports Ito and Pucik (1993); Hundley and Jacobson (1998). Accordingly, bribery creates advantages for firms in the domestic market cause of reducing the size of exports (Cuervo-Cazurra (2006)). These advantages make enterprises lose motivation to find customers or export goods to foreign markets, where they will no longer receive benefits as in the domestic market. Supporting this view, Lee and Weng (2013) found a negative relationship between bribes and firm export intensity. Specifically, a 1% increase in corporate bribery will reduce the power of exports to 1.43%. A similar result across 25 countries, mainly including countries in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, was found when Gamage (2019) analyzed the relationship between bribery payments and export intensity and found that the bribe payment rate increased from 0% to 8%, the firms’ export intensity decreasing by 9.25%. However, according to Olney’s findings Olney (2016), the effect of bribery on exports was only fully discernible if direct and indirect exports are classified separately. The results provided new evidence that the firms’ ability to export indirectly is increased if the firm makes a bribe. On the contrary, it reduces the ability of companies to export directly. Thereby, the author made an important suggestion in this study for developing countries where corruption is common. The intermediaries play an essential role in making a profit for the trade in making a profit for trade. Firms in these countries can enjoy success in exporting indirectly through intermediaries.

In summary, it can be seen that this interesting relationship is highly dependent on factors such as the characteristics of the firm, country, and survey period, etc. In particular, placed in different environments, this effect may be slightly deflected or reversed. Therefore, the literature on the influence of obstacles on bribery will be considered in the following section.

2.3. The Regulatory Role of Obstacles

The political instability creates a weak and unstable business environment Hiatt and Sine (2014). This instability hinders the development and causes adverse effects on the benefits of firms Garcia et al. (2008). In addition, it increases dependence on the government, one of the reasons for increasing corruption and bribery Xie et al. (2019). The strand of bribery literature revealed that regardless of the bribery form, “grease” or “sanding” the wheel, bribery depends a lot on the institutions and barriers to a firm’s operation, such as financial capacity, competitiveness, and a network of enterprises.

A weak institutional system is a cause of limiting the export capacity of enterprises. This fact is due to enterprises having difficulty obtaining export licenses and facing too many other complicated regulations Rose-Ackerman (1975). Krammer (2019) researched bribery in 30 emerging markets in Central Asia and Eastern Europe and showed that bribery offers many benefits to firms looking to innovate. However, whether this effect is positive or not depends on the formal and informal pressures of the institutional environment. He argued that bribery will be more successful in facilitating the launch of new products in countries with weak standard regulatory controls over corruption. These environments provided opportunities for officials to extort bribes. In turn, the already constrained institutional roadmaps become smooth, allowing companies to deploy new products more quickly Luo (2005). In contrast, solid formal institutions limited the influence of bribery on new product launches.

Additionaly, Svensson (2003) stated that the higher the barriers a firm faces, the more likely a firm will pay bribes. If a firm does not pay for this, it would have to exit the industry. Otherwise, a firm can refuse to pay bribes when obstacles are low without worrying about any retaliation.

The economy has many constraints on market entry that will hinder new businesses. Dreher and Gassebner (2013) found clear evidence that the number of new entrants is decreased when entry regulations are too complicated. This negative effect is reduced once the enterprise makes a bribe. However, Dreher’s claims were only considered short-term. The author doubted that bribery, or the influence of strict regulations and bulky legal procedures, is unknown in the long run.

Furthermore, Vial and Hanoteau (2010) argued that institutions influence economic activity by affecting exchange and production costs. Their study highlighted the threshold effects of institutions on the relationship between corruption and economic growth. Three institutional characteristics observed in the survey are political stability, property rights, and the political system. Political stability boosts production. When politics is stable, corruption and bribery cause disadvantages for tricky politics. However, in cases of severe political instability, corruption can help tie the economic system together for a while.

Notwithstanding, Klapper et al. (2006) only found the negative effect of institutional and regulatory barriers on the market entry opportunities of new firms in countries with low corruption rates or developing countries. For developing countries or high corruption index countries, the impediment of regulatory barriers does not cause a decrease in the number of new entrants to the market. The reason is that the bribery of these businesses can smooth the obstacles.

In summary, the reviewed literature demonstrated a comprehensive analysis of bribery and firms’ activities, including exports. Some of them analyzed the impact of institutions on bribery on some firms’ aspects, such as innovation and market entry. Therefore, this study is expected to connect and clarify the influence of firm’s growth obstacles in the interaction of bribery and export in separate analysis groups.

3. Research Approach and Data Description

This section focuses on two sets of main analyses. The first one scrutinizes the integration of obstacles and bribery payment. The second one analyses the effect of bribery on export intensity under a firm’s operation obstacles. Models are performed in turn on four separate income country groups, including low-income countries (LI), low-medium income countries (LMI), upper-medium income countries (UMI), and high-income countries (HI).

3.1. Estimation Strategy

- Analysis 1—Influence of Obstacles on Bribery

Based on their characteristics, firms offer a suitable amount of bribes to lubricate the wheels, thereby reducing the pressures of barriers in their operation. Consequently, a simple regression model is proposed to test the negative relationship between the two variables bribery and obstacles as follows:

represent bribery share of firm i, is the set of obstacles, while is the set of firm characteristics as a control variable. is an error term. All symbols and subscripts are maintained throughout this study.

Previous growth economic theories of firms have confirmed that an enterprise operating in the economy, of course, always has many binding relationships Box (2008). On the top of firms’ characteristics, environmental and structural factors also play an essential role in the success or failure of the company. Many scholars have classified firms’ obstacles into several categories: internal organizational obstacles, obstacles due to external market position, institutional obstacles, and financial obstacles Bartlett and Bukvič (2001).

In particular, internal barriers include the specific characteristic of the enterprise such as shortage of skilled workers, weak management capacity, etc. These factors are considered the foundation of a firm’s operations, thus determining its success or failure Watson et al. (1998). Likewise, the barriers regarding competition, the general situation of a firm in the industry, demand for the product, access to raw materials, commercial rules, etc. are considered obstacle factors from the market environment outside the company. These factors can support or hinder the operation and survival of the business Olawale and Garwe (2010). One of the most challenging barriers worthy of attention in enterprises are financial barriers, including lack of equity capital or barriers concerning credit access such as high credit costs, bank fees, and collateral constraints. Researchers point out financial constraints as playing an essential role in the business and investment decisions of enterprises. For example, Kapplan and Zingales (1997) found the sensitivity of financial constraints to firms’ investment cash flows; Greenaway et al. (2007); Bellone et al. (2010) showed a link between financial restrictions and decisions export. Finally, institutional obstacles play a critical role in firm performance. According to North (1989), institutional constraints include norms, conduct practices, and judicial rules that a company encounters.

Thus, these difficulties at different levels affect the development of enterprises. Although many firms expect to solve problems with bribes, bribery is indeed unlikely to solve all problems. Gamage (2019) showed that several barriers interfere directly with a company’s bribery decision, but others interfere indirectly. For example, the tax bracket applicable to a business is determined by law, which is very difficult to change by bribery or the pressure from competitors has a binding relationship with the company’s outcome. These factors may not be the factors that directly influence the firm’s bribery decision but are the indirect factors that motivate the enterprise to bribe to expand production.

As a consequence, in these models, I choose a set of three obstacles including tax administration (marked as taxad), business licensing and permit constraints (denoted as permit), and political instability (denoted as pol) as direct factors that affect bribery of a firm. Thus, the set of obstacles is .

In addition, because model 1 includes a fractional dependent variable, the outcomes observed are bounded within the range of [0, 1]. According to Wooldridge (2015), the Probit regression is suitable. Then, I report the predictive margins of each obstacle on firm bribery payment over a firm’s export status. Thus, the results provide a detailed and comprehensive view of the impact of each perceived impediment on bribery at 95% confidence intervals, comparing exporting and non-exporting firms.

- Analysis 2—Influence of Bribery Payment on Export Intensity

To shed light the impact of bribery on export intensity which includes all relevant control variables, I regress model (3)1:

where subscripts i,j,s denote firm, country, and sector, respectively. v, are year and sector fixed effect. represent bribery share of firm i, is the set of obstacles, while the set of firm characteristics as a control variable. is an error term.

Then I scrutinise the influence of paying bribes on the export percentage under a firm’s growth barriers by adding some obstacles into Model 4. As mentioned above, a firm’s growth obstacles might be divided into four groups. Instead of using institutional obstacles as analysis 1, this section selects obstacles that are likely to affect business operations (such as exports) and indirectly affect bribery in the three remaining groups. For simplification, I select one obstacle from each of the remaining groups. The obstacle representing each group is the one that most businesses consider to be the biggest obstacle. They are practices of a competitor in the informal sector (denoted as compe), inadequacy of a skilled worker (denoted as inade), and financial constraint (marked as fin).

where is the set of obstacles.

Because is a fractional dependent variable, I apply the Probit method to estimate Equation (models 3 and 4). In addition, to eliminate the unobservable factor specific to countries and sectors, I use v, as year and sector fixed effect Thanh et al. (2021). In addition, as an endogenous issue of bribery, models (3) and (4) are then estimated by using Instrumental Probit Regression (IV-Probit regression) with “the location-country-sector average of bribery” as an instrumental variable Bernard et al. (1995), Thanh et al. (2021). A simple procedure for estimating this model is that the bribe variable is assessed as a linear equation of the instrumental variable and other explanatory variables to estimate bribes’ value in the first stage Wooldridge (2015). This stage is expected to indicate a strong correlation between firm-level bribery and instrument variables, implying that the province-sector average bribery rate is a relevant tool for explainiing firm-level bribery. Then, export is estimated as a function of the values calculated from the first stage and other exogenous variables. In all regressions, I report the average margin effect.

- Further Sensitive Analysis

- (i)

- Consider Each Obstacle Separately

Instead of including all three obstacles (competition, inadequately skilled worker, and financial obstacles) as model 4, in this section I examine model 4 for each barrier to comparing the effect of a firm facing and not facing an obstacle. Through this process, the interaction effect between obstacles and bribery payment can be observed more thoroughly. Notwithstanding that these constraints do not directly affect the bribery decision, their existence can cause pressure on the enterprise’s business process. From there, indirectly, these difficulties affect the scale of bribery of enterprises. Enterprises may decide to increase bribes to ensure business objectives, namely export revenue. The situation can also be reversed when the appearance of constraints is too strong, leading to the effect of bribery becoming blurred in promoting bribery. Thus, by analyzing the interaction coefficient between bribes and obstacles, their impact on the export size of enterprises becomes more accurate. Regressions are conducted on four sub-data samples regarding the national income.

- (ii)

- SMEs and Large-Sized Firms

Firm size plays an essential role in all activities of firms, especially bribery Beck and Demirguc-Kunt (2006). As a result, they are also more often stimulated to bribe. To test this hypothesis, I run models 1–4 for SMEs and large firm-size separately and then compare all the results. The regression process is similar to the main model analysis.

3.2. Data and Variables

This study combines two data sources. First, the latest Enterprises Survey provided by the World Bank and published in early 2021, that crosses 131 countries. Second, the World Bank’s 2020 National Income Classification report categorizes countries according to income groups (see Appendix A for the list of countries). This section discusses variables in detail. Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics.

Table 1.

Statistical description of variables.

In this research paper’s scope, enterprises’ bribery is considered to be informal payments to state administrative agencies or customers to gain advantages and priorities in operation. This paper discusses the bribery payment of firms as a percentage of annual revenue, denoted as BriS. Values for this variable will also have a scope from 0 to 100. Bribery payment is a dependent variable in regressions of analysis 1. Additionally, it is an independent variable in regressions concerning analysis 2.

This study uses the total direct export sales percentage as a dependent variable in the regressions regarding analysis 2. The export share (denoted as ExS) ranges between 0 and 100. Furthermore, some firm-specific characteristics are included as control variables. The logarithm value of total employees in a firm will be used as a proxy for firm size (denoted as fsize) Seker and Yang (2012). Firm age (marked as fage) is measured as the difference between the year surveyed and the year firms are established. In this study, the logarithm of age’s value will be used (as Roberts and Tybout (1997)). Moreover, foreign ownership has the potential to influence a firm’s decision to enter the international market and its decision to participate in bribery Abor (2008)2. Consequently, this study creates a dummy variable (marked as own). Its value equals one if the firm is owned 10% or more by foreign individuals, companies, or organizations, 0 if otherwise. Moreover, similar to some previour studies as Thanh et al. (2021), this paper also controls some other factors including managing experience of owner (named as mae), international certification (represented as ctfc), research and development (RnD), innovation of the firm (marked as inno), having contact with government gos, the capacity utilization cau, and exporting firm dummy (denoted as exp).

As mentioned above, this study uses two groups of firms’ obstacles. For analysis 1, business and permit constraints (denoted as permit), political instability (denoted as pol), and tax administration (marked as taxad) are chosen. Furthermore, for analysis 2, the set of practices of a competitor in the informal sector (denoted as compe), inadequately skilled worker (represented as inade), and financial constraint (marked as fin) are used as moderating variables. Enterprises self-assess the levels of barriers that they face. Their perception of obstacles was assessed at the following levels: no obstacle, minor obstacle, moderate obstacles, major obstacle, and very severe obstacle.

4. Findings and Discussions

4.1. Endogeneity

Addressing the endogenous problem of bribes to avoid bias in estimating bribes’ impact is a recognized concern in many previous studies. This inhomogeneity can be caused by a number of reasons. First, no matter whether passive or active bribery, the bribery level is inconsistent between businesses. The response of a firm to bribery depends on its ability to pay. For example, officials may ask for more bribes at highly profitable enterprises because they believe that these firms are willing to pay more in exchange for the benefits Svensson (2003). Furthermore, companies with different business strategies and perceptions have different tolerance levels for a bribe to benefit. As such, bribery is not random, and it can correlate with unobserved firms’ characteristics Seker and Yang (2012). Second, as outlined in the literature review, the interaction between bribery and export can be a simultaneous relationship. For example, paying bribes can increase costs and reduce labor productivity, creating obstacles for firms entering or expanding export markets. In contrast, exporters can take advantage of bribe’ payments to bypass the complicated bureaucracy and exporting goods procedures. Third, some scholars argue that micro-data collected from the same source at the firm level, such as informal corporate payments and performance enterprises, export activities, are likely to lead to endogenous problems Birhanu et al. (2016).

The endogenous problem of bribery can be resolved by applying the instrumental variable approach Wooldridge (2015). A suitable instrument must correlate to the endogenous explanatory variable but not to the dependent variable. As suggested in recent empirical studies, this study also uses the locality-sector-country average of bribery as an instrumental variable for firm-level bribery Mendoza et al. (2015); Seker and Yang (2012). Accordingly, bribes are averaged across all other firms in the exact location and sector but exclude them. Because bribery is expected to be diverse in different industries and positions, it tends to be dominated by the average level of bribery in its sector—its region. Thus, using the location–sector–country average of the bribery can eliminate unobserved deviations in the correlation between the firm’s export decision and bribery activity. As in previous studies, this study uses “the location–sector–country average of bribery” as an instrumental variable (denoted as ).

The endogenous tests will be performed and presented in Table 2. These results provide evidence to confirm that the instrumental variable is valid and has adequate power in mitigating the endogeneity problem.

Table 2.

Test for the endogenous variable.

4.2. Estimation Results

Following the empirical settings, the Probit and IV-Probit methods are used to test models, and all results are reported in this section. This study classifies the data into four country groups regarding the national income, including low-income countries (LI), low-medium income countries (LMI), upper-medium income countries (UMI), and high-income countries (HI). Then, to clarify the role of firm size, the sample data is classified according to two different size groups, namely SMEs and large enterprises, in the further sensitive analysis.

- Analysis 1: The Effect of Obstacles on Bribery Payment

The results are presented in Table 3. Columns 1, 3, 5, and 7 are the results of regressions without the set of control variables (model 1), and columns 2, 4, 6, and 8 are the results of model 2.

Table 3.

Compare the influence of obstacles on bribery in four country groups.

Alongside this, the negative correlation coefficients of the control variables support the previous hypothesis. Larger firms tend to pay fewer bribery shares than smaller firms. Similarly, characteristics such as high-capacity utilization, international certifications, and research and development (R&D) activities imply that a firm can operate efficiently, with high quality. A good firm can this avoid informal payments to lobby for its operations. Nevertheless, the estimates do not find a clear relationship between firm age and bribe payment. Except for firms in the UMI country group (column 6), firm age has a positive and statistically significant effect on the bribery share, as the coefficient is 8.6% and . In other groups the coefficient is insignificant ().

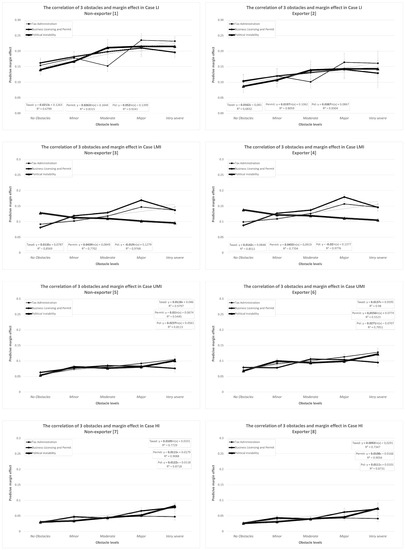

Second, this study predicts the effect of firms’ perceptions in paying bribes and compares non-exporting firms (named as non-exporter) and exporting firms (named as an exporter) to further assess the impact of each perceived level of barriers on bribery payment. A visual representation of images makes it possible to compare the differences between the analysis groups more quickly. Therefore, a visualization of the predicted marginal effects of three constraints in four country groups on bribery share at the 95% confidence interval is shown in Figure 1. As a result, the set of obstacles has a significant marginal effect on the firm’s bribery share on all levels of obstacle severity (p < 0.01) in both export status groups.

Figure 1.

A visualization of the predicted marginal effects of three constraints in four country groups on bribery share at the 95% confidence interval. Comparisons between non-exporters and exporters were made within each country group. In particular, subfigure 1 and 2 are in LI countries, subfigures 3 and 4 are in LMI countries, subfigure 5 and 6 are in UMI countries, and subfigure 7 and 8 are in HI countries.

In general, most of the coefficients of all three hindrances show a positive and statistically significant relationship with the bribery payment at a 1% level. These findings imply that firms are likely to increase their bribery rates as pressures from barriers increase, such as stricter tax and business license administration in government agencies, and political instability becomes more severe. Among the three types of obstacles, tax management barriers have the strongest impact on increasing the probability of bribery of enterprises, except three cases in columns 1, 4, and 8. For example, the influence of the tax administration in the UMI countries (columns 5 and 6), accounts for the highest proportion of the three obstacles, regardless of with or without control variables in the model. Even so, the influence of the taxad variable is only half that of the effect of political instability on bribe payments by firms in the HI group (0.055 compared with 0.113 in column 8). In addition, political instability in LMI countries has a negligible effect on bribe payments. Regression results in column 3 and 4 record the correlation coefficient of these two variables (pol and briS) only are 0.015 and 0.047, respectively.

At first glance, the graph’s shape of the correlation between obstacles and the predictive margin of bribery is quite similar between exporters and non-exporters in each country group. However, the gap between lines in non-exporter compared with those in exporter might be more recognizable in the LMI group (Figure 1(5,6)). Additionally, there is no significant difference in the rest of the country groups. This result is obtained through observing and comparing the slopes in the prediction equations. Comparing different country groups, an interesting feature is that in two groups of LI and HI countries, the impact of non-exporters awareness levels in all three types of barriers on bribery is higher than that of exporters. Meanwhile, the situation is opposite in medium-income nations, including LMI and UMI countries.

Then, going into detail, the relationship between tax administration and the probability of bribery is predicted as a positive linear function, except in HI group (Figure 1(5,6)). The impact of tax administration on the marginal effect of bribery is waning with the income nation level. The results show that this effect is strongest in low-developed countries (group LI), and lowest in developed countries (group HI). Specifically, the graph steadily increased with a smaller amplitude in the UMI and HI groups, compared with the other two groups. Besides, the marginal effect of bribe payments is mainly highest at the major level of tax administration, except in the UMI countries (Figure 1(5,6)).

In addition, the correlation between the permit and the margin probability bribery is predicted in terms of a linear function in HI group, instead of saturation function like the rest of the groups. All functions are positive. From (Figure 1(1–4)), the probability of bribery of firms in LI and LMI countries tends to increase gradually as regulatory barriers become increasingly difficult. This effect then becomes saturated when the licensing constraints reach the “Major” threshold. Legal systems in underdeveloped and developing economies are often quite cumbersome, with overlapping functions between state agencies. As a result, firms need to have enough experience and take a lot of time to process procedures, such as business licenses. In such a weak legal system, bribery tends to be promoted in businesses, to “smooth” this process. However, when legal barriers become too severe, this can result in businesses not being able to afford to continue to push the payment of bribes, or that bribery cannot help firms to overcome these barriers. Thus, at the “Major” hindrance level, the probability of bribery becomes saturated. Although this trend is similar in UMI firms, the effect of licensing barriers in these countries is only a quarter of the impact in the LMI group, and half the impact in the LI group. The correlation coefficient of the permit and the bribe margin effect in the UMI group is about 0.01 compared with around 0.045 in the LMI group and 0.02 in the LI group. Unlike other groups, the correlation between the permit and predictive margin effect of bribery in the HI group is consistent with the linear function (Figure 1(7,8)). Then, the obtained value is over 90% in both exporting and non-exporting groups. Whereas if the function is described as quadratic or saturated, the value of is almost insignificant (below 40%).

Similarly, the functions representing each relationship between the political instability and the bribery marginal probabilities are mostly saturation predicted, with values in the range from approximately 80% to more than 97%, excepting the group HI (Figure 1(7,8)). The effect of political instability on the bribery margin probability is more notable than others. Specifically, the impact of pol was 2-fold higher than the effect of tax administration in the LI group (Figure 1(1,2)) and the UMI group (Figure 1(5,6)), respectively. An interesting finding is that in contrast to other groups, the effect of political instability in LMI countries is represented as a negative function.

In brief, the results support the argument that the three types of constraints directly affect the firm’s bribery payments. The positive relationship between them supports the idea that when firms perceive an increase in a firm’s obstacles, they spend more informal amounts on bribes. Graphically and intuitively, the degree of influence of all three constraints on the probability of bribery in the HI countries is the least volatile. There is almost no big difference between the base level (“No obstacles”) and the rest of the levels. The explanation for this problem may be due to the characteristics of developed countries such as the development of the state management system, the perfection of the legal and institutional system, the political stability, and the low level of national corruption. As an effect, firms find it difficult to find loopholes to engage in bribery. This argument might be appropriate because it is also likely to be relevant for the opposing group. This argument may be relevant because it also can account for the opposing group. Bribery probabilities of firms in low-developed countries (LI) are strongly influenced by the degree of impediment.

- Analysis 2: The Effect of Bribery Payment on Export

Table 4 presents the results of models 3 and 4 by IV-Probit regression, comparing different country groups. Model 3’s coefficient for bribery is both positive and significant at a 1% level in two groups of medium-income nations (columns 3 and 5). In particular, a firm’s export as the share of export sales in LMI and UMI groups is likely to increase to 2.1% and 3.6% point once a firm increase bribe, respectively. By contrast, there is a negative relation between bribery payment and the firm’s export share in nations with a high-income level HI (column 7). Approximately 11.4% drop in the probability of exports was recorded at a 5% significant level () when a firm pays more for informal payments. These findings are similar to Gamage (2019) covering 25 countries in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. She found that the bribe payment rate increased from 0% to 8%, the firms export intensity decreasing by 9.25%. Nevertheless, there is no evidence for the effect of bribery on exports in the LI country group. The coefficient of bribery is not statistically significant in both models that exclude and include control variables (columns 1 and 2). In addition, comparing the results of model 3 and model 4, the influence of obstacles makes the correlation coefficient of bribery decrease, though the gap is negligible. This result shows that bribery is less effective when enterprises face obstacles such as an external competitive environment, lack of skilled labor, and higher financial constraints.

Table 4.

The effect of bribery payment on export in different country groups.

A part from this, in the set of control variables shown in the result table, firm size, international certificate, RnD, and foreign ownership are factors that have a notable effect on export activity. All characteristics positively affect exports and are statistically significant at the 1% level in all regressions in which the large-sized firm is more likely to export than smaller firms (30% on average). Similarly, the higher the foreign ownership and/or holding the international certification, the more likely the firm increases exports (40% and 60% on average, respectively). Research and development activity tends to powerfully impact the export probabilities of firms in a developed economy (HI group). RnD can increase the likelihood of export growth of this group by nearly 47% (column 8), nearly double that of the other groups. In addition, there is no evidence for the impact of state contracts and capacity utilization on export activity in these estimates.

I predict the margin effect of bribery payments on a firm’s export share to comprehensively analyse results. Through the intriguing results of marginal effect ranges, it is possible to analyze the responses of exports to changes in each level of bribery. Table 5 presents the detailed results. In the LI group, starting from over 50% of bribery payments, the margin effects are no longer significant, as (). When a firm pays more bribery from 0% to 40%, the probability of export increases by 27.9% (column 1). Similarly, the results in LMI are significant up to the 30% rage of bribery payment (Column 3). In addition, the results in the UMI group are statistically significant in most of the bribery ranges, except the 20% range (Column 5). Compared with the same degree of bribery payments, once a firm raises a bribery payment from 0% to 30%, export probability also goes up in both LMI and UMI groups. Export’s likelihood in UMI countries increases by approximately 106%, over 1.5 times higher than in the LMI group. Finally, the more extensive the bribery range, the lower the likelihood of exporting firms in the HI group. The results in the HI group are significant across all ranges of bribery. These results infer that when the bribe value increases by 30%, the probability of exporting decreases from probability (−0.107) to probability (−2.658).

Table 5.

Predictive margins of bribery share on export.

In a nutshell, this study finds the positive effect of bribery payment on firms’ export in nations belonging to the medium-income countries group, but negative influence in high-income countries. Moreover, no evidence is found for the rest group (LI). Moreover, the effect of bribery on exports becomes more pronounced when considering firms’ obstacles. The visualization of the margin results provides a clearer view of the impact of perceived barriers on the relationship between bribery and exports.

- Further Sensitive Analysis Results

- (i)

- Consider Each Obstacle Separately

In contrast to the main model, instead of controlling for the effects of all three constraints simultaneously, this section examines the interaction of each in turn on the relationship between bribe payment and exports. The similarity with the main part of the model is that the set of control variables remains the same, and the regressions are performed on 4 sub-data classified by country income group. Table 6 reports the results of the regressions. From the comparison between firms without difficulty (No) and with difficulty (Yes), it is possible to highlight the interaction between obstacles and bribery in relationship with exports.

Table 6.

The effect of bribery on export under each obstacles separately.

Overall, bribe payments have absolutely no relationship with exports in the LI group. Moreover, the presence of hindrance changed the relationship between bribery and export, from insignificant to significant in HI group. In the other two groups, the correlation coefficients are significant, regardless of whether the enterprise faces obstacles or not.

Specifically, panel A reports that the rate of bribe payment of enterprises in the LI group is not able to explain the change in export probability, because the correlation coefficients are all significantly greater than 10%. This result is consistent with the results in the main model (Table 4). Comparing the number of observations between the groups facing and not facing obstacles, the number of enterprises with difficulties is more than that of enterprises without obstacles. Even the number of firms in LI that are financially constrained is three times more likely than unrestricted firms (columns 5 and 6). However, compared with the number of observations in the rest of the country groups, the figure in the LI group was the lowest, ranging from 376 to 1131 observations. The limitation of the sample may be the reason why we question the consistency of the population.

Panel B and panel C reflect the positive outcomes of bribery in the LMI and UMI groups. Although the correlation coefficient is significant even when firms do not face impediments, the presence of impediments reduces the magnitude of the impact of bribery on exports, comparing columns 1, 3, 5 and columns 2, 4, 6, respectively, in pairs. These results are similar to the main part (results in Table 4), but the effect of bribery on export probability is stronger when observing each type of hindrance separately. To illustrate this point, for firms in LMI facing financial difficulty, the effect of bribery is strongest. The probability of exporting is then likely to increase by 0.021 (column 6), compared with 0.015 (column 2) and 0.018 (column 4) once these businesses face competition, or lack of skilled workers, respectively. In contrast, the effect of bribery was strongest for firms in UMI that face competitive difficulties (correlation coefficient 0.037), compared with firms facing the other problems. Interestingly, however, when comparing the disparity caused by the impediment, the results reflect an opposite trend. The most significant reduction in the impact of bribe payments in the LMI group (panel B) was due to competition, from 0.038 (column 1) to 0.015 (column 2). Whereas, in the UMI (panel C), the change caused by financial constraints is the most pronounced, from 0.064 (column 5) when a firm is not facing financial difficulties to 0.033 (column 6) when it is facing financial constraint.

Finally, no different from the main result (Table 4), panel D reflects the negative outcome of bribe payments to exports by firms in the HI group. Under the interaction of competition and lack of skilled workers, the association between bribery and export becomes statistically significant. The magnitude of the effect of bribery when considering the interaction of bribery and these two constraints is −0.186 (Column 3) and −0.173 (Column 4), respectively. This result is much higher than the effect of bribery when controlling for all three constraints in the main model simultaneously (Column 8–Table 4). The cause of this finding is that financial constraints do not change the nature of the relationship between bribery and exports in the HI group. The ability to export is not affected by bribery regardless of the firm’s financial position, as the correlation coefficients are not statistically significant (columns 5 and 6—panel D–Table 6).

To sum up, the results obtained when separating each constraint are in favor of the main results. In more detail, the interaction between competition and bribery makes the effect of bribery on exports strongest in the UMI and HI groups. While the interaction between financial constraints and bribery makes the effect of bribery on exports strongest in the LMI group.

- (ii)

- SMEs and Large-Sized firms

In this further analysis, the study approaches the main models on SMEs and large-sized firms. First, the results of model 1 and model 2 for SMEs and large-sized firms are shown in Table 7. Regardless of firms’ size, the scale of a firm’s bribery tends to increase once firms face more severe difficulties in tax administration, business licensing procedures, and political instability (columns 1 and 3). This result may reduce when controlling for firm characteristics as control variables (columns 2 and 4). The results also show that political instability has the least influence on bribery payment compared to the other two barriers, regardless of SMEs or large companies. These findings aline with the results of the main part.

Table 7.

Robustness test results of analysis 1 by firm size.

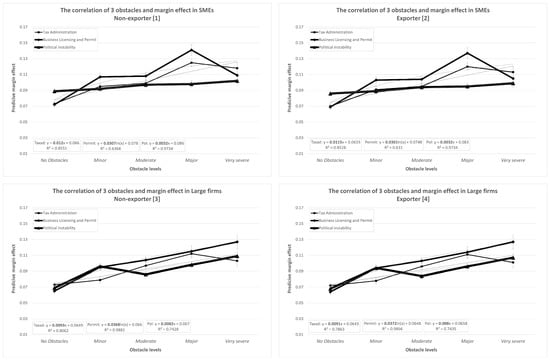

In addition, Figure 2 visually depicts the predicted marginal effects of these constraints in both firm-size groups at the 95% confidence intervals relative to the export situation. All three obstacles have a significant marginal impact on the payment of bribes at all obstacle levels, as . Overall, it is immediately apparent that the shapes of the graphs are similar between exporting and non-exporting firms in both SMEs and large firms. The correlation between tax impediment and the marginal prediction of bribery increases gradually with a positive linear function. However, the growth rate in the group of SMEs is slightly higher. Likewise, the graph of the political instability variable can also be predicted as an increasing linear function. While political instability has almost no discernible effect on the bribery behavior of SMEs, large firms find a notable variation in the probability of bribery when it faces with uncertainty politics. Illustrating this point, the graph is steep as the firm moves from the starting point (no obstacle) to the beginning of perceived difficulty due to corruption (minor obstacle). However, the degree of variation in the likelihood of bribery increases slowly at the next difficulty levels. Unlike the above two hindrances, the relationship between permit and the marginal effect of bribery is most appropriate with a saturation function, as the coefficients are greater than 64% in SMEs, and over 98% in large firms. When a firm begins to perceive business licensing and permit impediments, the probability of bribery gradually increases in both groups of firms, before becoming saturated when impediment reaches Major level. In short, tax administration barriers have a stronger impact on bribery behavior of SMEs than large firms. In contrast, the latter is more dominated by political instability and bureaucratic difficulties.

Figure 2.

Visually depicts the predicted marginal effects of these constraints in both firm-size groups at the 95% confidence intervals relative to the export situation. Comparisons between non-exporters and exporters were made within each country group. In particular, subfigure 1 and 2 are in SMEs group, and subfigure 3 and 4 are in large firms group.

Second, the effect of bribery on exports is tested by IV-probit estimation using the location–country–sector average of bribery as the instrumental variable (models 3 and 4). The results are presented in Table 8. Columns 1 and 2 reflect the results for SMEs. The results emphasize that an increase in bribe payments can account for an increase in exports (the coefficients are statistically significant at the 1% level, ). SMEs paying more bribes can increase their ability to export. Specifically, in the baseline model (Model 3) and the model that controls for the specific characteristics of the enterprise (Model 4), the ability to export can increase to 1.6% and 1.8%, respectively. On the other hand, no relationship was found between bribe payments and exports in large firms (Column 4). The correlation coefficient between bribery and exports is not statistically significant even when I add control variables to the model (column 5). In addition, although competitive pressure from competitors reduces the export ability of both SMEs and large enterprises, its impact on SMEs is almost twice as high, −0.074 (Column 2) compared with −0.037 (Column 4). This finding is the same expected result as Ito and Pucik (1993). Furthermore, though the shortage of high-skilled labor is significant for export activities of enterprises, the regressions do not find a significant difference of this factor for the probability of paying bribes of SMEs and large corporations. Unlike the above two types of impediments, the study only found evidence of a negative interaction of financial constraints on the relationship between bribery and exports in the large group of firms (column 4). In contrast, no relationship of financial problems was found in the SMEs group (column 2).

Table 8.

Robustness test results of analysis 2 by firm size.

All in all, regardless of firm size, obstacles related to tax administration, business licensing and permit, and corruption all explain the variation in corporate bribery probabilities. The relationship was found to be positive. However, the study only found a link between bribery and exports in the case of SMEs, but did not find any indication of this association in large firms.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

An enterprise operating in production and business always faces many barriers regarding external obstacles (such as institutional, regulatory, and competitive difficulties of the business environment) and internal obstacles (such as the lack of capital and skilled labor, etc). On top of that, firms also always face negative pressures caused by harassment in various forms by administrative agencies such as lobbying, kickback, grease payment, etc. This situation seems to be more acute in countries with high levels of corruption, where there are gaps in government regulation to create space for fraud and solicitation. These barriers, directly or indirectly, affect the outcome of the firm.

This paper adopts firm-level data cross-country provided by the World Bank, combined with the World Bank’ 2020 National Income Classification. The empirical study aims to demonstrate two main issues: (1) whether there is a relationship between the firm’s obstacles and the firm’s bribe payments; and (2) does bribery have an impact on the firm’s operations, in particular on exports? How these impacts will change under the intervention of the levels of obstacles that a firm faces.

Estimations are conducted on four subgroups, which the World Bank classifies using the national income. Then, we estimate the models on two subgroups by firm size in the robustness test. The results find a positive relationship of all three barriers, including tax administration, business licensing, and political instability, to bribery payments across all groups classified by national income and firm size. Institutional inefficiencies are the driving force behind corporate bribery. Gaps in administrative management push firms to be willing to engage in bribes. From then they might exchange for advantages. However, these illegal activities of firms are not a solution with long-term benefits. Its consequences not only cause losses to business operations such as reduced labor productivity Dutta and Sobel (2016) but also cause an unhealthy business environment, inhibiting the development of the economy Gründler and Potrafke (2019). Therefore, policymakers can focus on reforming the bureaucracy, shortening cumbersome procedures, increasing support for businesses in administrative procedures such as tax declaration, applying for permits, etc. to combat under-table activities. In particular, for less developed countries, the goal of increasing the effectiveness of the tax administration system should be prioritized. Because the decrease in efficiency of this activity is very meaningful in creating pressure for enterprises to participate in bribery. In addition, the bribery practices of SMEs are more sensitive to institutional inefficiencies. This result can be explained by the well-known characteristics of SMEs such as lack of experience, lack of knowledge, and ability to negotiate with harassment by authorities. Therefore, policies to support SMEs need to be concretized and implemented.

In the second analysis of the paper, we find empirical results that support the “greasing the wheel” view of the group of developing countries. This conclusion implies that firms can generate export advantages through lobbying bribes. In contrast, the bribery behavior of firms in developed countries (HI group) does not bring advantages to firms’ exports. The relationship between bribery and exports is negative. In addition, our study found no relationship between bribery and exports in the least developed countries (LDCs). In addition, three problems including competition, lack of skilled human resources, financial constraints are known to be three common hindrances of enterprises in the development process. We find evidence that the effectiveness of informal payments is significantly reduced when firms face such constraints, especially those in middle-income countries and SMEs.

However, these results imply that bribery creates unfairness in international market participation among firms. This is a potential risk for the sustainable development of the economy. Therefore, measures to limit corruption, as well as bribery, should be given due attention. These results suggest several policy implications. In which, to ensure equality in the business environment, businesses and the state need to have close coordination. For example, the government needs to overcome cumbersome procedures and legal barriers to create more favorable conditions for businesses to access capital. In addition, human resource training policies to meet the needs of high-skilled workers for export businesses should also be focused on. The strengthened internal strength of the business is also likely to increase the resistance of the business to harassment and illegal solicitation from bureaucrats. Furthermore, internal barriers are more severe in SMEs Bartlett and Bukvič (2001). Our paper finds significant effects of bribery payment on exports in this group of firms. Therefore, governments need to have specific policies and pay more attention to this group of businesses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.H.P.; methodology, T.H.P.; software, T.H.P.; formal analysis, T.H.P.; data curation, T.H.P.; writing—review and editing, T.H.P. and R.S.; supervision, R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We acknowledge support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG—German Research Foundation) and the Open Access Publishing Fund of Technical University of Darmstadt.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed to support the findings of the present study are included this article. The raw data can be obtained from the authors, upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The list of countries *.

Table A1.

The list of countries *.

| Low Income Countries | Low-Medium Income Countries | Upper-Medium Income Countries | Hight Income Countries |

|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | Angola | Albania | Barbados |

| Burkina Faso | Bangladesh | Argentina | Belgium |

| Burundi | Benin | Armenia | Chile |

| Central African Republic | Bhutan | Azerbaijan | Croatia |

| Chad | Bolivia | Belarus | Cyprus |

| Drc | Cambodia | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Czech Republic |

| Eritrea | Cameroon | Botswana | Estonia |

| Ethiopia | Cape Verde | Brazil | Greece |

| Gambia | Congo | Bulgaria | Hungary |

| Guinea | Côte d’Ivoire | Bulgaria | Israel |

| Liberia | Djibouti | China | Italy |

| Madagascar | Egypt | Colombia | Latvia |

| Malawi | El Salvador | Costa Rica | Lithuania |

| Mali | Ghana | Dominica | Luxembourg |

| Mozambique | Honduras | Dominican Republic | Malta |

| Niger | India | Ecuador | Mauritius |

| Rwanda | Kenya | Gabon | Panama |

| Sierra Leone | Kyrgyzstan | Georgia | Poland |

| South Sudan | Lao PDR | Guatemala | Portugal |

| Sudan | Lesotho | Guyana | Romania |

| Tajikistan | Mauritania | Indonesia | Slovakia |

| Togo | Moldova | Iraq | Slovenia |

| Uganda | Mongolia | Jamaica | Sweden |

| Yemen | Morocco | Jordan | Trinidad and Tobago |

| Myanmar | Kazakhstan | Uruguay | |

| Nepal | Lebanon | ||

| Nicaragua | Malaysia | ||

| Nigeria | Mexico | ||

| Pakistan | Montenegro | ||

| Papua New Guinea | Namibia | ||

| Philippines | North Macedonia | ||

| Senegal | Paraguay | ||

| Sri Lanka | Peru | ||

| Tanzania | Russia | ||

| Timor-Leste | Serbia | ||

| Tunisia | South Africa | ||

| Ukraine | Suriname | ||

| Uzbekistan | Thailand | ||

| Vanuatu | Turkey | ||

| Vietnam | Venezuela | ||

| Zambia | |||

| Zimbabwe |

Note: * Country classification by income based on World bank’s publication 2020.

Notes

| 1 | Thanks to Thanh et al. (2021) for the idea considering the effect of obstacles. However, they focused on four types of institutional obstacles. In this study, the obstacles come from the firm’s side (the internal obstacles) and are observed more detail in sub-datas. |

| 2 | According to Abor (2008), companies with more than 10% foreign equity often have better access to information related to foreign markets. Ownership of more than 10% in companies that demonstrate the right to express an opinion at the general meeting of shareholders can influence decisions in the company’s operations. |

References

- Abor, Joshua. 2008. Determinants of the Capital Structure of Ghanaian Firms. Nairobi: African Economic Research Consortium. [Google Scholar]

- Asiedu, Elizabeth, and James Freeman. 2009. The effect of corruption on investment growth: Evidence from firms in Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, and transition countries. Review of Development Economics 13: 200–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aw, Bee Yan, Sukkyun Chung, and Mark J. Roberts. 2000. Productivity and turnover in the export market: Micro-level evidence from the Republic of Korea and Taiwan (China). The World Bank Economic Review 14: 65–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyagari, Meghana, Asli Demirgüç-Kunt, and Vojislav Maksimovic. 2014. Bribe payments and innovation in developing countries: Are innovating firms disproportionately affected? Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 49: 51–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, Will, and Vladimir Bukvič. 2001. Barriers to SME growth in Slovenia. MOST: Economic Policy in Transitional Economies 11: 177–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, Thorsten, and Asli Demirguc-Kunt. 2006. Small and medium-size enterprises: Access to finance as a growth constraint. Journal of Banking & Finance 30: 2931–43. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, Paul J., and Michael W. Maher. 1989. Competition, regulation and bribery. Managerial and Decision Economics 10: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellone, Flora, Patrick Musso, Lionel Nesta, and Stefano Schiavo. 2010. Financial constraints and firm export behaviour. World Economy 33: 347–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, Andrew B., J. Bradford Jensen, and Robert Z. Lawrence. 1995. Exporters, jobs, and wages in US manufacturing: 1976–1987. Brookings papers on economic activity. Microeconomics 1995: 67–119. [Google Scholar]

- Birhanu, Addis G., Alfonso Gambardella, and Giovanni Valentini. 2016. Bribery and investment: Firm-level evidence from Africa and Latin America. Strategic Management Journal 37: 1865–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, Marcus. 2008. The death of firms: Exploring the effects of environment and birth cohort on firm survival in Sweden. Small Business Economics 31: 379–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, Nauro F., Saul Estrin, and Eugenio Proto. 2010. Corruption As A Barrier to Entry: Theory and Evidence. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1711074 (accessed on 22 November 2010).

- Cariolle, Joël, and Petros Sekeris. 2021. How Export Shocks Corrupt: Theory and Evidence. Available online: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03164648/document (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Coase, Ronald Harry. 1937. The nature of the firm. Economica 4: 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobham, Alan. 1954. Priority assignment in waiting line problems. Journal of the Operations Research Society of America 2: 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo-Cazurra, Alvaro. 2006. Who cares about corruption? Journal of International Business Studies 37: 807–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Bó, Ernesto, and Martín A. Rossi. 2007. Corruption and inefficiency: Theory and evidence from electric utilities. Journal of Public Economics 91: 939–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, Donato, Nishaal Gooroochurn, and Holger Görg. 2010. Corruption and Productivity Firm-Level Evidence from the BEEPS Survey. No. 5348, Policy Research Working Paper. Washington, DC: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Dreher, Axel, and Martin Gassebner. 2013. Greasing the wheels? The impact of regulations and corruption on firm entry. Public Choice 155: 413–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, Nabamita, and Russell Sobel. 2016. Does corruption ever help entrepreneurship? Small Business Economics 47: 179–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisman, Raymond, and Jakob Svensson. 2007. Are corruption and taxation really harmful to growth? Firm level evidence. Journal of Development Economics 83: 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, Randika Eramudugoda. 2019. Bribery and Export Intensity: The Role of Formal Institutional Constraint Susceptibility. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/271295a3563213c42456a2bd39a44b3e/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 1 May 2019).

- Gao, Gerald Yong, Janet Y. Murray, Masaaki Kotabe, and Jiangyong Lu. 2010. A “strategy tripod” perspective on export behaviors: Evidence from domestic and foreign firms based in an emerging economy. Journal of International Business Studies 41: 377–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Canal, Esteban, and Mauro F. Guillén. 2008. Risk and the strategy of foreign location choice in regulated industries. Strategic Management Journal 29: 1097–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedhuys, Micheline, Pierre Mohnen, and Tamer Taha. 2016. Corruption, innovation and firm growth: Firm-level evidence from Egypt and Tunisia. Eurasian Business Review 6: 299–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenaway, David, Alessandra Guariglia, and Richard Kneller. 2007. Financial factors and exporting decisions. Journal of International Economics 73: 377–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gros, Daniel. 2013. Foreign Debt versus Domestic Debt in the Euro Area. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 29: 502–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenendijk, Nico. 1997. A principal-agent model of corruption. Crime, Law and Social Change 27: 207–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gründler, Klaus, and Niklas Potrafke. 2019. Corruption and economic growth: New empirical evidence. European Journal of Political Economy 60: 101810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellman, Joel, and Mark Schankerman. 2000. Intervention, corruption and capture: The nexus between enterprises and the state. Economics of Transition 8: 545–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J. Vernon, and Ari Kuncoro. 2004. Corruption in Indonesia. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w10674 (accessed on 18 July 2004).

- Hiatt, Shon R., and Wesley D. Sine. 2014. Clear and present danger: Planning and new venture survival amid political and civil violence. Strategic Management Journal 35: 773–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundley, Greg, and Carol K. Jacobson. 1998. The effects of the keiretsu on the export performance of Japanese companies: Help or hindrance? Strategic Management Journal 19: 927–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]