5.2. Answers to the Research Questions

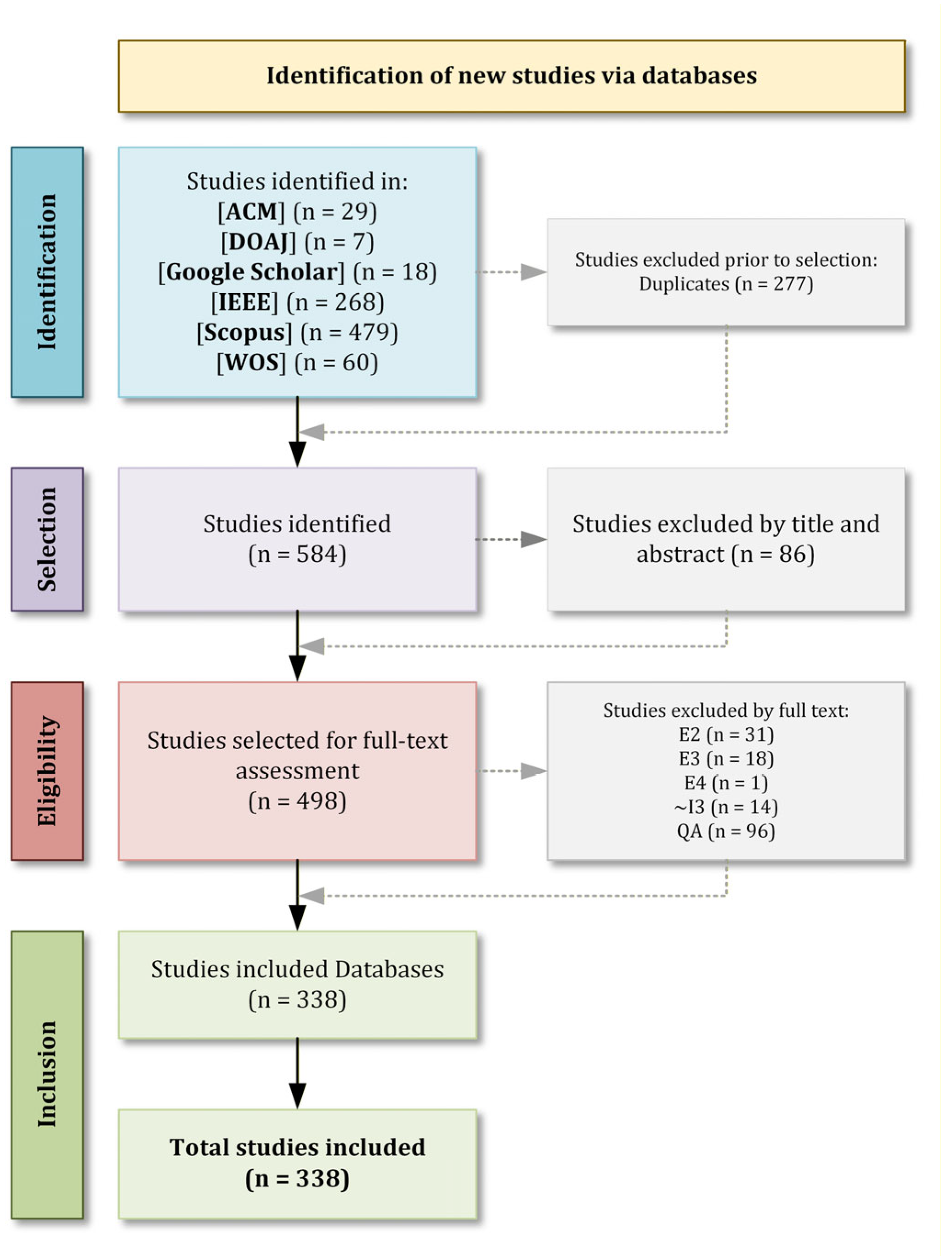

The answers to the research questions were obtained by extracting, synthesising, and combining data from the 338 studies.

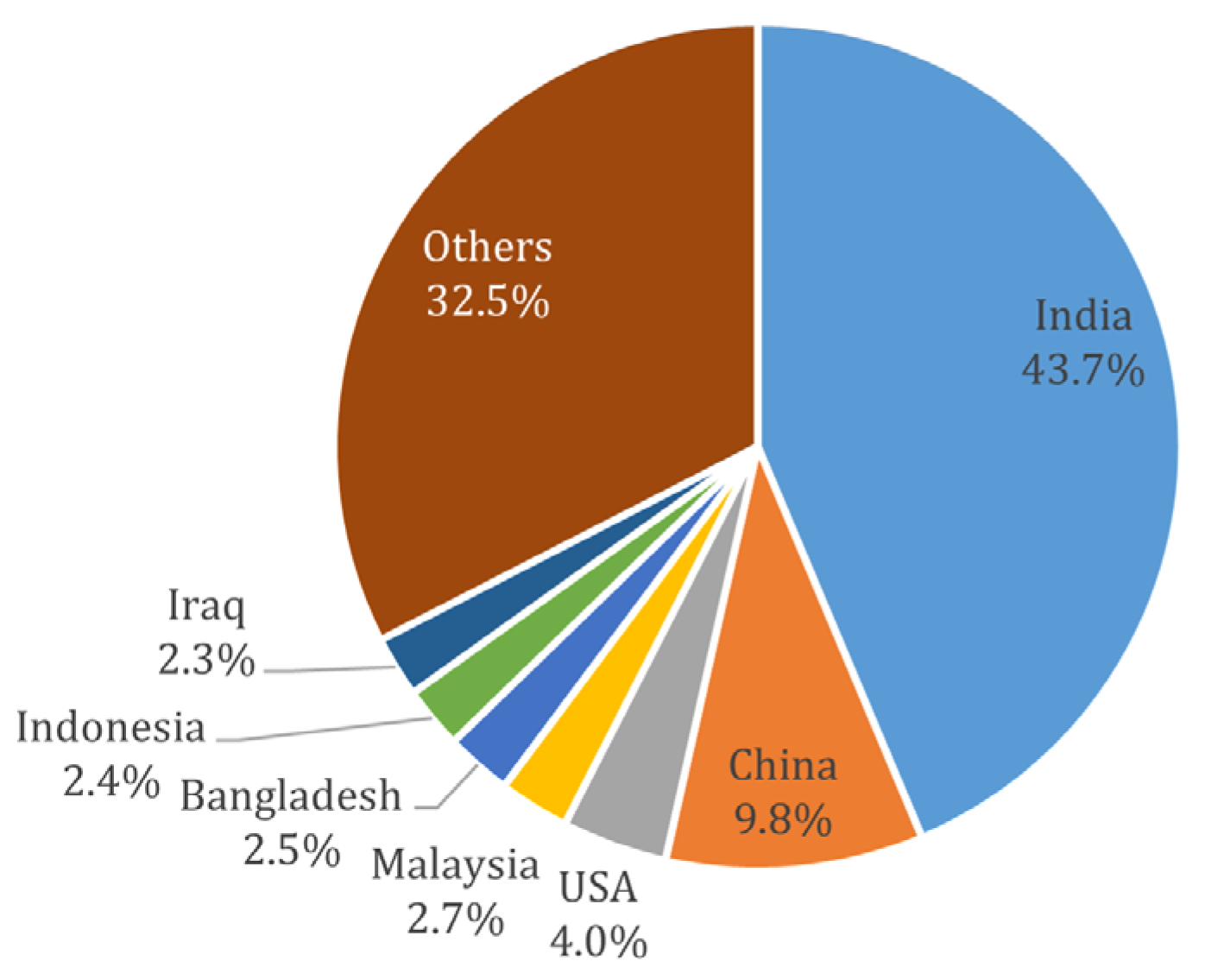

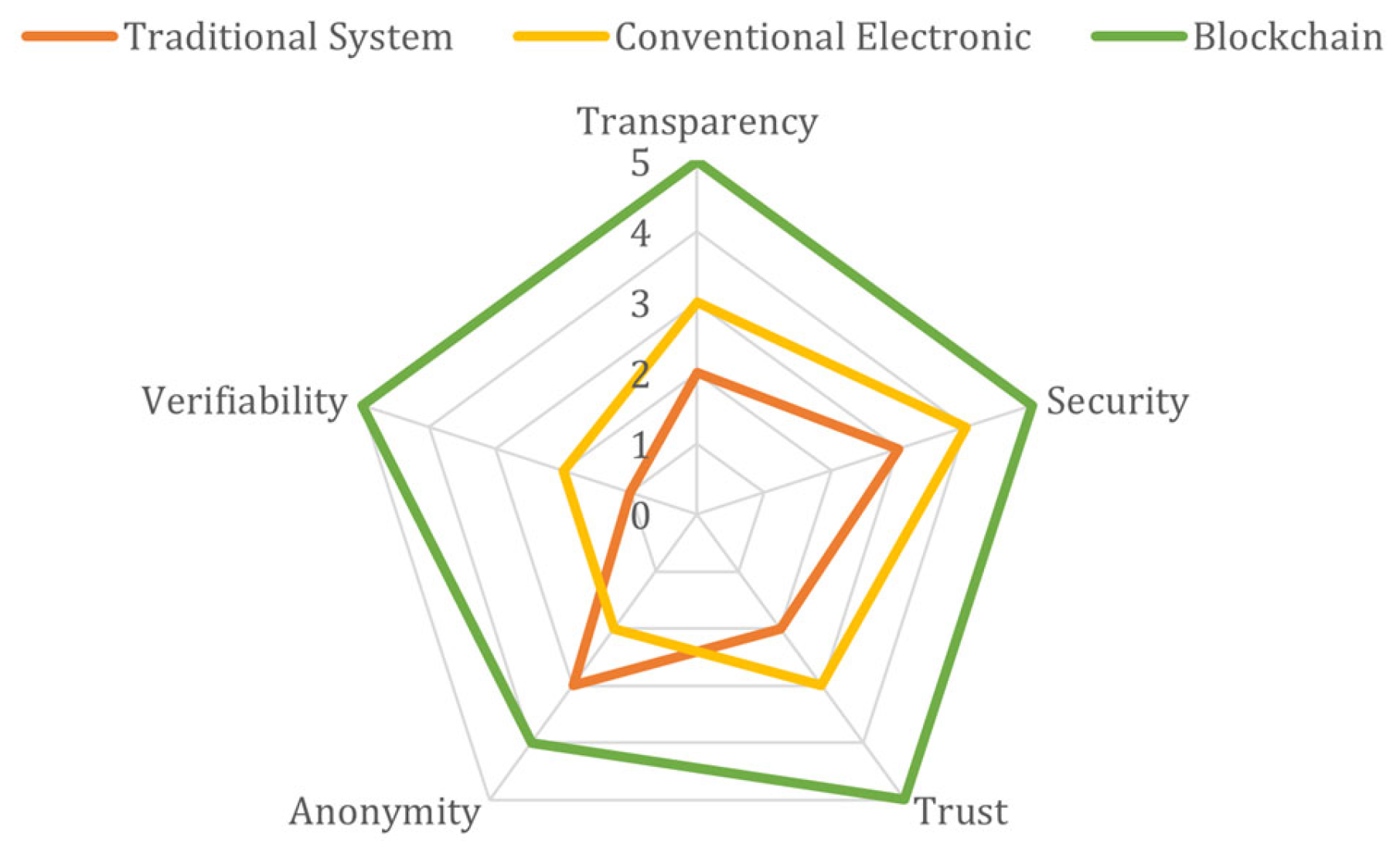

RQ1: How do blockchain-based electronic voting systems compare to traditional and electronic systems in terms of transparency, security, and trust?

The studies reviewed agree that blockchain-based electronic voting systems represent a significant advance over traditional and conventional electronic systems, especially in terms of transparency, security, and trust. Most proposals exploit the inherent properties of blockchain technology, such as immutability, node distribution and verifiable public record, to mitigate historical risks associated with vote manipulation, centralisation of power and lack of traceability.

One of the most recurrent contributions is the guarantee of electoral transparency without compromising the secrecy of the vote. For example, the study by Hamidey and Heng [

8] states that their decentralised proposal allows any voter to verify the recording of their vote without revealing its content, thus eliminating the need to trust central authorities. Along the same lines, Spadafora et al. [

16] introduce coercion-resistant mechanisms that improve voter confidence, even in contexts of external pressure.

In terms of security, multiple systems integrate advanced cryptographic techniques (e.g., blind signatures and zero-knowledge proofs) to protect the integrity and confidentiality of votes. The study by Chen et al. [

5] highlights the use of homomorphic cryptography and computationally verifiable anonymity mechanisms, which allow votes to be counted securely without compromising the identity of voters.

The explicit comparison with traditional or previous electronic systems is addressed in greater depth in studies such as that by Huang et al. [

1], which argues that combining blockchain with self-tallying mechanisms eliminates potential fraudulent intermediaries while improving the efficiency and credibility of the electoral process.

However, some studies acknowledge that these theoretical improvements still require more robust empirical validation, especially in real-world contexts with high participation and sophisticated threats [

24,

25,

26].

To compare the capabilities of traditional voting systems, conventional electronic systems, and blockchain-based systems, a radar chart has been constructed (see

Figure 7) that summarises their relative performance in five fundamental criteria: transparency, security, trust, anonymity, and verifiability. This representation is derived from a critical synthesis of primary studies and allows us to intuitively highlight the advantages offered by blockchain technology over previous models. The values assigned to each system in each criterion reflect the most recurrent and robust findings identified in the reviewed literature.

Table 7 below references some studies for each of the criteria analysed:

Blockchain-based electronic voting systems are emerging as a solid alternative to the limitations of previous models, thanks to their cryptographic guarantees and distributed structure. However, their widespread adoption still depends on contextual validations and improvements in usability and scalability.

RQ2: What proposals for blockchain-based electronic voting systems have been developed and implemented in academic or university contexts, and which ones have shown the best results?

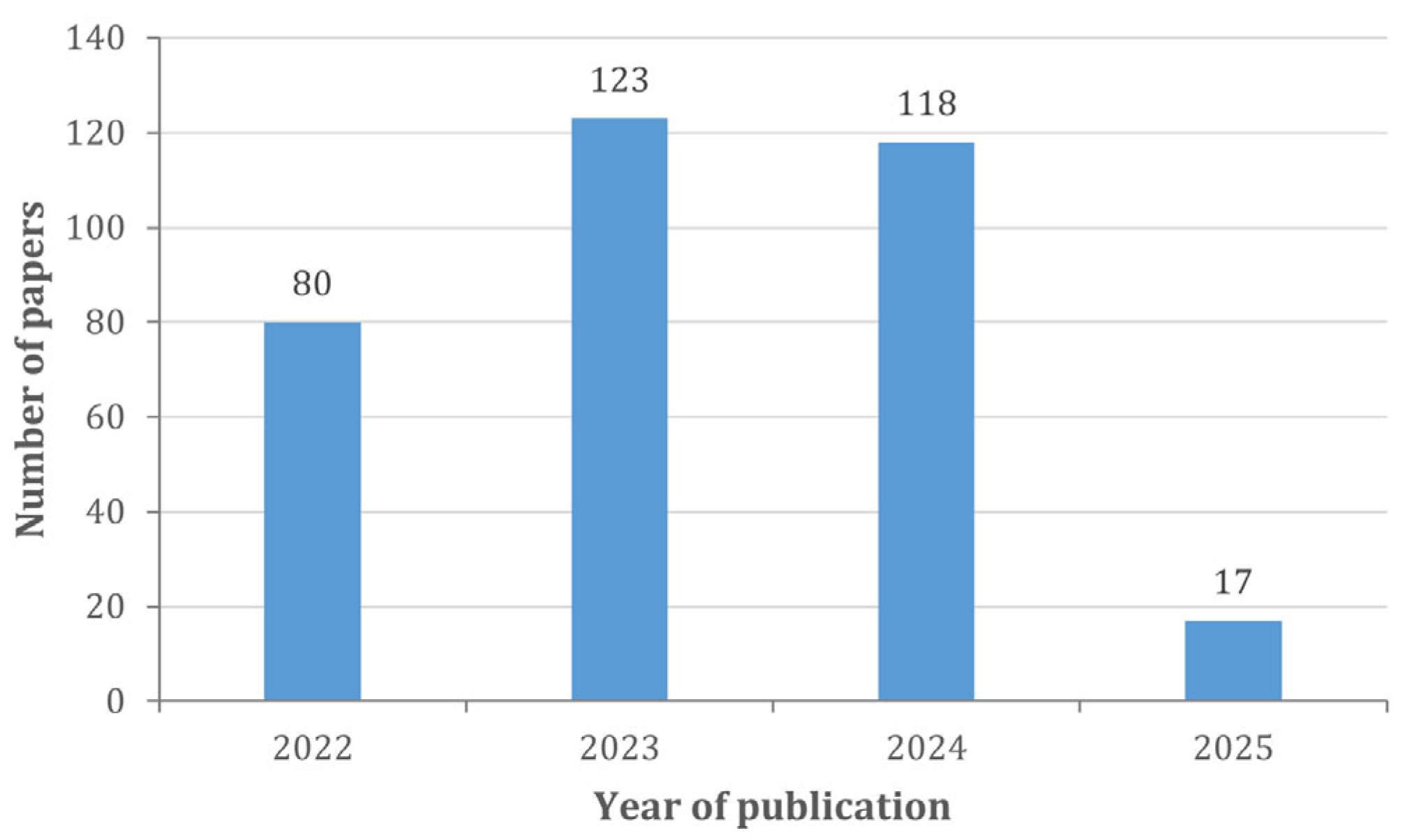

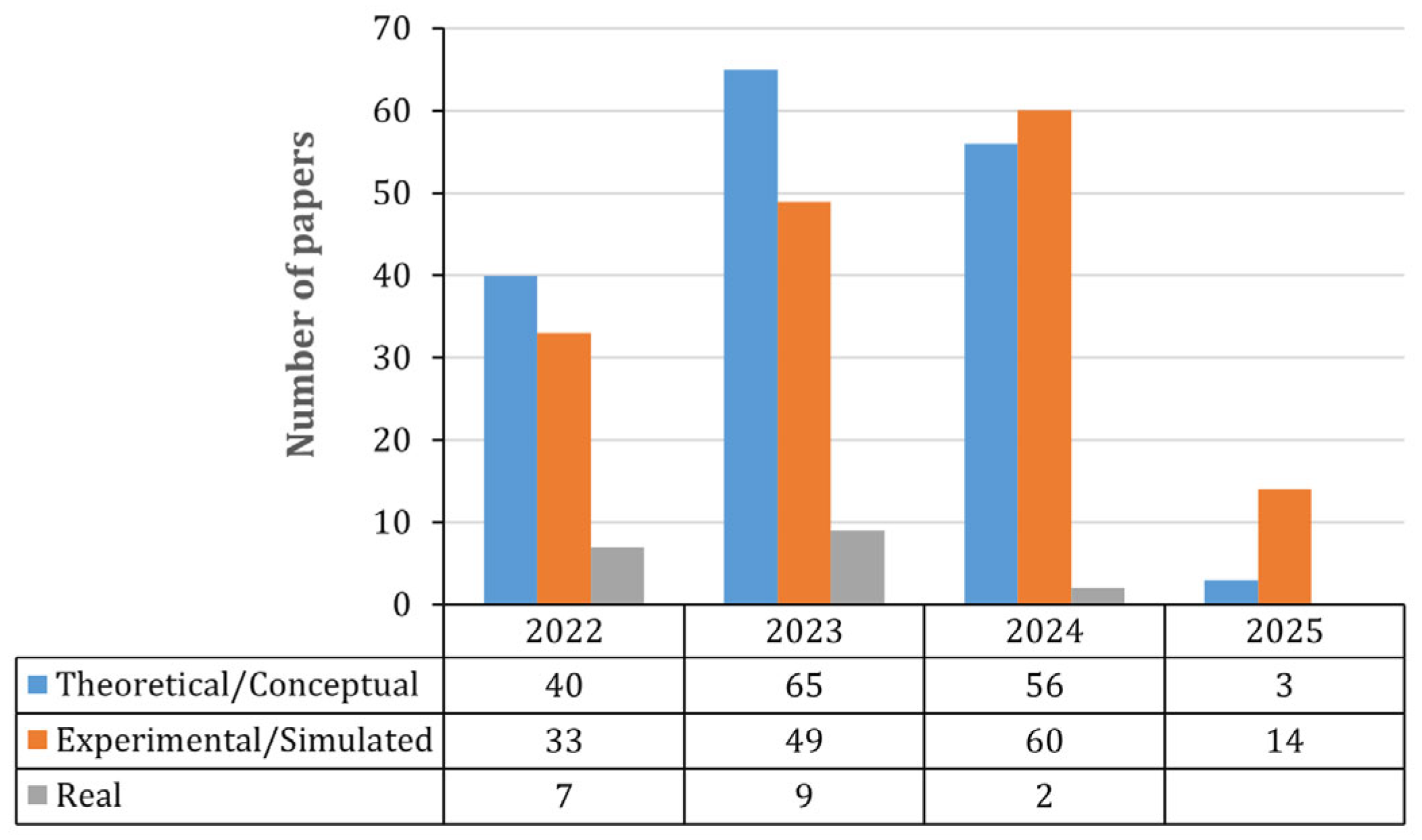

Findings on the application of blockchain-based electronic voting systems in academic or university settings reveal an emerging, diverse landscape that still faces practical implementation challenges. Although literature is largely dominated by theoretical works and simulations focused on general or national contexts, concrete progress has been made in recent years, with some studies reporting applied experiences or pilot projects in academic settings.

A small number of studies report pilot applications in academic institutions, although generally without detailed reports on impact or systematic results. A significant example is the study by Pereira et al. [

38], which describes the implementation of a decentralised system with real-time results validation and auditing, successfully used in academic elections, highlighting as a contribution the robustness of privacy through advanced cryptography and verifiable end-to-end mechanisms. Similarly, Bhamare et al. [

35] emphasise the applicability and acceptance of Ethereum platforms with smart contracts in real university electoral processes, reporting improvements in transparency, speed of counting, and participant confidence.

In terms of technological frameworks, both public blockchains (Ethereum, NEAR Protocol) and permissioned blockchains (Hyperledger Fabric) predominate, adjusted according to institutional requirements for anonymity, traceability, and access control. The work of Marouan et al. [

14] reports on its effective application in a Moroccan university, achieving optimal results in terms of efficiency and security compared to traditional manual systems, relying on digital signatures, PoW and PoS consensus, and smart contracts to eliminate manual counting and ensure integrity. Similarly, Torre et al. [

39] present a positive validation in student elections, highlighting that the use of OTP and unique cryptographic keys allowed anonymity and auditability to be preserved without storing real identities.

Among the achievements observed, the reduction of manipulation risks, automatic vote auditing, improved processing times, and the possibility of public scrutiny stand out. However, it remains clear that many of the studies with more innovative approaches, for example, the use of zero-knowledge proofs or hybrid mechanisms with biometrics and multi-factor authentication, remain in the conceptual testing phase, without direct empirical evidence on campuses or in real elections [

40,

41].

It should be noted that there are significant differences: while studies such as those by Adeniyi et al. [

17] and Zhang et al. [

41] report only limited experimental evidence without real institutional validation, other proposals have reached pilot stages, allowing for the measurement of impact in areas such as usability, acceptance, and fraud reduction, as is the case with the studies by Bhamare et al. [

35] and Duran et al. [

42].

Table 8 lists some of the most relevant studies developed and applied in real academic contexts.

Although the field shows robust technical development, implementation in educational contexts remains more of a promise than a reality. The experiences reported are isolated and lack systematic validation. Future research should focus on real-world deployments, integrating organisational, regulatory, and cultural factors that condition the adoption of these technologies in academia.

RQ3: What implementation techniques and types of blockchain networks have been used in electronic voting system proposals, and how do they address the main challenges of security, anonymity, and verification?

Recent literature on blockchain-based electronic voting systems reveals a rapidly evolving ecosystem characterised by a diversity of technical approaches to addressing classic challenges: security, anonymity, and verification. The primary studies analysed agree on the use of public blockchains (such as Ethereum and Solana), private blockchains (Hyperledger Fabric), or consortium blockchains, selected based on the application context, scale, and governance requirements [

3,

13,

14].

In terms of implementation techniques, the use of smart contracts is practically universal, enabling the automation of processes such as voter registration, ballot casting and counting, and result validation. Ethereum stands out for its flexibility and broad ecosystem of development tools, although the cost of “gas” and scalability limitations are recurring concerns [

25,

45]. The integration of advanced cryptographic technologies is central to privacy and integrity. Ring signatures, blind signatures, and zero-knowledge proofs are being adopted, allowing voter anonymity to be balanced with end-to-end verifiability [

46,

47].

Security is addressed through homomorphic encryption, the use of public/private keys, and the explicit separation between authentication and voting processes, preventing the voter’s identity from being linked to their individual vote. Some systems explore the integration of biometrics (fingerprints, facial recognition) as a strong authentication mechanism, although generally combined with robust encryption to prevent direct correlation between identity and vote [

9,

48].

In terms of verification, many designs adopt public auditing mechanisms: votes are recorded immutably and transparently on the blockchain, allowing voters and external observers to independently validate results [

3,

38]. The trend toward self-verification and decentralised counting (self-tallying) is also notable, favoured by the possibilities of smart contracts and advanced cryptography.

Table 9 summarises the key technical and functional aspects that determine the design of these systems and allows for a comparison of how different combinations of components address historical problems with electronic voting (especially the dilemmas of security, anonymity, and verifiability). The modular structure facilitates the selection of the most appropriate architectures and techniques according to the regulatory context, the level of confidence required, and the scale of implementation.

The studies reviewed show conceptual and technical maturation in the field: the combination of blockchain with advanced cryptographic techniques makes it possible to increasingly respond to the challenges of security, anonymity, and verifiability, although challenges remain in scalability, efficiency, and validation in real-world scenarios.

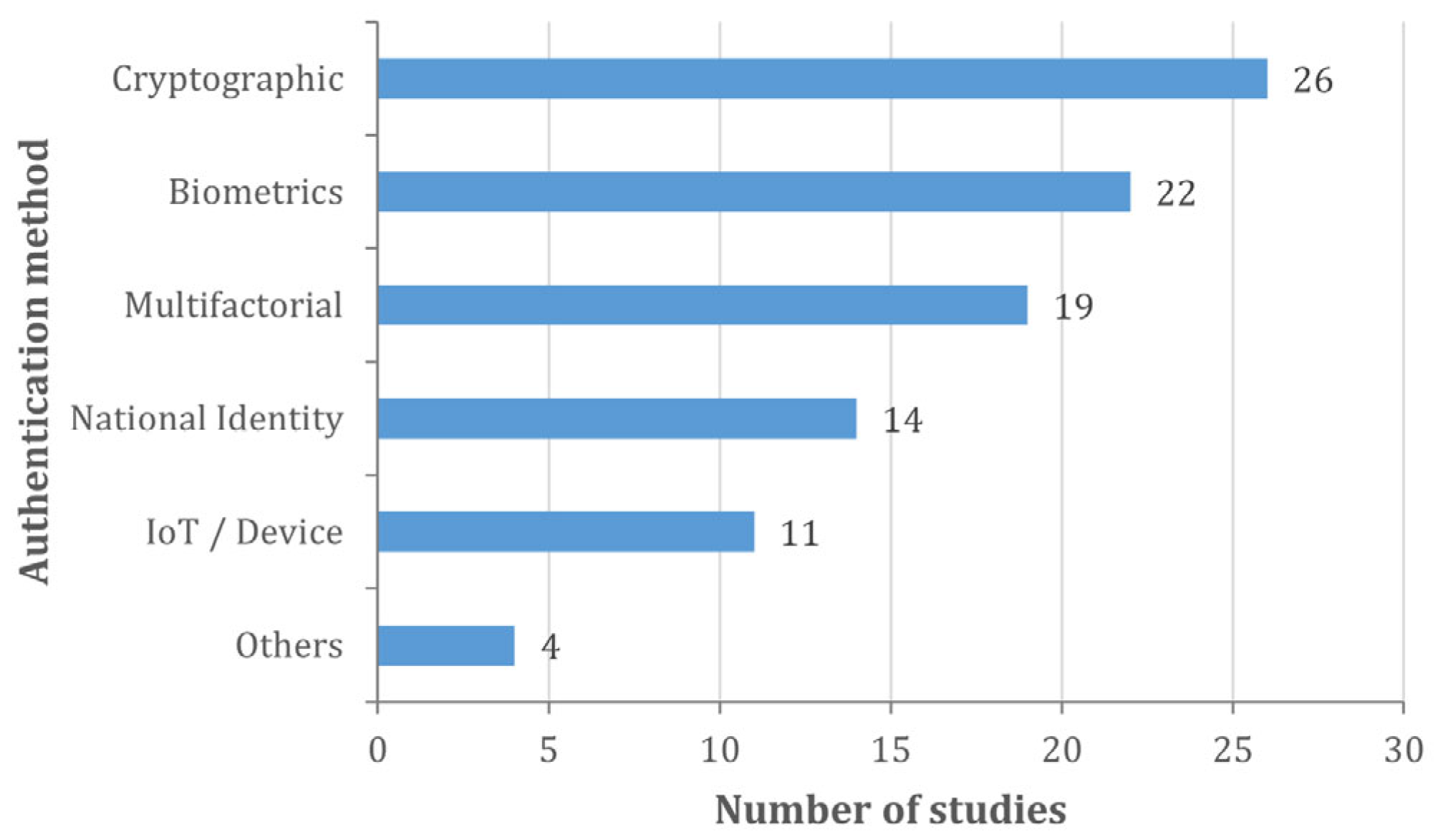

RQ4: What voter authentication methods have been used in blockchain-based electronic voting solutions, and how do they balance identity and anonymity?

The integration of authentication methods into blockchain-based electronic voting systems reveals clear trends aimed at balancing robust identity verification with the preservation of voter anonymity. The recurring approaches identified in the studies reviewed fall mainly into three broad categories: biometrics, advanced cryptographic techniques, and national identity systems.

On the one hand, biometric authentication (fingerprints, facial recognition) is positioned as an effective mechanism for strengthening security and minimising identity fraud, without automatically compromising anonymity. This is achieved using public keys derived from biometrics or asymmetric techniques, which authenticate participation but protect identity during the registration and voting phases, as exemplified by studies such as those by Adeniyi et al. [

17] and D. Kumar & Kumar Dwivedi [

49].

A second relevant group consists of cryptography-based authentication solutions, notably ring signature schemes, blind signatures, ZKPs, and distributed thresholds. These methods make it possible to verify voter eligibility and uniqueness without linking individual identity to the vote cast. For example, in the works of Chen et al. [

5] and Sangraula & Adhikari [

6], cryptographic authentication is used to ensure that the verification process always remains unlinked to the content of the vote, preserving anonymity and avoiding direct traceability.

Thirdly, the integration of national identities (such as Aadhaar, social security numbers (SSN), or unique tokens generated from government databases) constitutes a robust authentication alternative, especially in models that seek high interoperability and eligibility control. Studies such as that by Jain et al. [

50] demonstrate how an acceptable balance can be achieved by associating pseudonymised or encrypted credentials—sometimes combined with one-time passwords (OTPs)—with the authentication process, preventing the tracking of votes or real identities during the counting phase.

Other emerging approaches include multifactorial schemes (biometrics combined with OTP, facial recognition powered by machine learning) and authentication anchored in mobile devices or IoT sensors, which reinforces the robustness of the process without compromising privacy [

18,

49,

51].

Figure 8 visually summarises the frequency with which the different approaches appear in the included primary studies, based on the following main categories of authentication:

Biometric (fingerprints, facial recognition, finger vein, iris).

Cryptographic (ring signatures, blind signatures, zero-knowledge proofs, hashes).

National identity-based (Aadhaar, SSN, government ID cards).

Multifactorial (combinations of OTP with biometrics, two- or more-step authentication).

Device/IoT (validations by mobile devices, IoT sensors, QR codes).

Other/Miscellaneous (methods not covered by the above).

It should be noted that not all the 338 studies included in the review explicitly reported authentication mechanisms. Therefore, the analysis presented in

Figure 8 considers only the 96 studies that provided sufficient and explicit information regarding user authentication methods, which explains the reduced sample size in this specific result.

The figure shows a clear and hierarchical distribution of the authentication methods used in blockchain-based electronic voting systems, revealing a marked preference for cryptographic techniques (26 studies), followed by biometric (22) and multi-factor (19) approaches. This distribution suggests a trend toward solutions that seek to balance technical security and practical usability. Only 96 studies are included instead of the 338 resulting from the review, as some did not provide sufficient or relevant information for this research question and were excluded from this summary. Furthermore, the subset reflected is a representative sample that illustrates predominant patterns and trends, facilitating interpretation without the noise produced by marginal or incomplete data.

Cryptographic methods lead the way due to their ability to guarantee integrity, anonymity, and non-repudiation in voting processes. The use of blind signatures, zero-knowledge proofs, and hashes has established itself as a robust basis for verifying and protecting identities without compromising voter privacy. This predominance demonstrates the research community’s alignment with advanced cybersecurity standards.

Secondly, biometric mechanisms, such as facial recognition or fingerprinting, stand out for their ability to offer non-transferable, highly reliable authentication, especially in contexts with limited access to electronic identity documents. However, their implementation poses ethical and technical challenges associated with the protection of sensitive personal data.

Multifactor schemes—combining OTP, biometrics, and passwords—are emerging as an adaptable response to contexts where a balance between robustness and accessibility is required. The variety of combinations suggests an attempt to strengthen security without compromising the user experience.

For its part, the use of national identity (14 studies) is limited to countries where there are centralised interoperable registries, such as Aadhaar in India. Although they promote inclusion, these systems can raise concerns about surveillance and state dependency.

Device- and IoT-based methods (11) show an emerging exploration of mobile technologies and sensors, suitable for urban contexts and remote voting. However, their reliability depends on the available technological infrastructure.

Finally, the category Others (4 studies) groups together experimental or hybrid proposals that do not yet fit into dominant classifications, reflecting the exploratory nature of some recent approaches.

Overall, the picture reveals an evolving ecosystem, where methodological diversity reflects the search for secure, inclusive solutions adapted to different socio-technical realities. Future adoption will depend on the ability to integrate these technologies while respecting democratic principles, privacy, and transparency.

Although studies are advancing with increasingly integrated solutions—where cryptographic methods allow for the separation of authentication and voting—practical and conceptual challenges remain about total verification without identity leakage. However, the combination of biometrics, advanced cryptography, and national identity management represents the core of current technological progress. The field shows technical maturity and a diversity of alternatives, although the perfect balance between reliable authentication and absolute anonymity remains the great challenge and driver of innovation in blockchain e-voting research.

RQ5: What verification and auditing methods have been applied to ensure the integrity and reliability of blockchain-based electronic voting systems?

Verification and auditing of blockchain-based electronic voting systems is essential to ensuring their integrity and reliability. Critical and combined analysis of the primary studies extracted reveals a remarkable diversity of approaches, although all converge on the need for robust verification mechanisms to counter threats such as vote manipulation and guarantee transparency for participants.

Among the recurring methods, the use of smart contracts as automated tools for auditing and verifying the electoral process stands out. Several proposals use smart contracts on platforms such as Ethereum to independently validate the integrity and immutable record of each vote, ensuring transparency and allowing it to be audited by any node in the network [

25,

52]. Automation significantly reduces the risk of human intervention and associated errors.

Another relevant avenue is advanced cryptographic mechanisms. For example, the use of ZKPs and homomorphic encryption allows votes to be counted and verified without compromising voter privacy [

8,

53]. Systems that implement ring signatures and blind signatures also provide public verifiability and resistance to linking votes to identities, thus balancing transparency and anonymity [

5].

Universal and individual verifiability is another cross-cutting issue. Several studies enable mechanisms for both voters and third parties to audit the correct inclusion of votes, whether through public hashes, blockchain explorers, or the disclosure of records without revealing sensitive information [

42,

43]. Similarly, some systems allow for the receipt of cryptographic receipts, which provide voters with certainty that their votes have been recorded without alteration [

16].

On the other hand, studies applied in university contexts demonstrate the validity of experimental audits and hybrid systems that combine public and private blockchains, highlighting end-to-end traceability and the value of simulation in strengthening trust before large-scale adoption [

3,

14].

However, methodological challenges remain, especially regarding the scalability of verification in large-scale elections and robust protection against possible attempts at coercion or vote buying; some studies address these limitations through self-scrutiny protocols [

1].

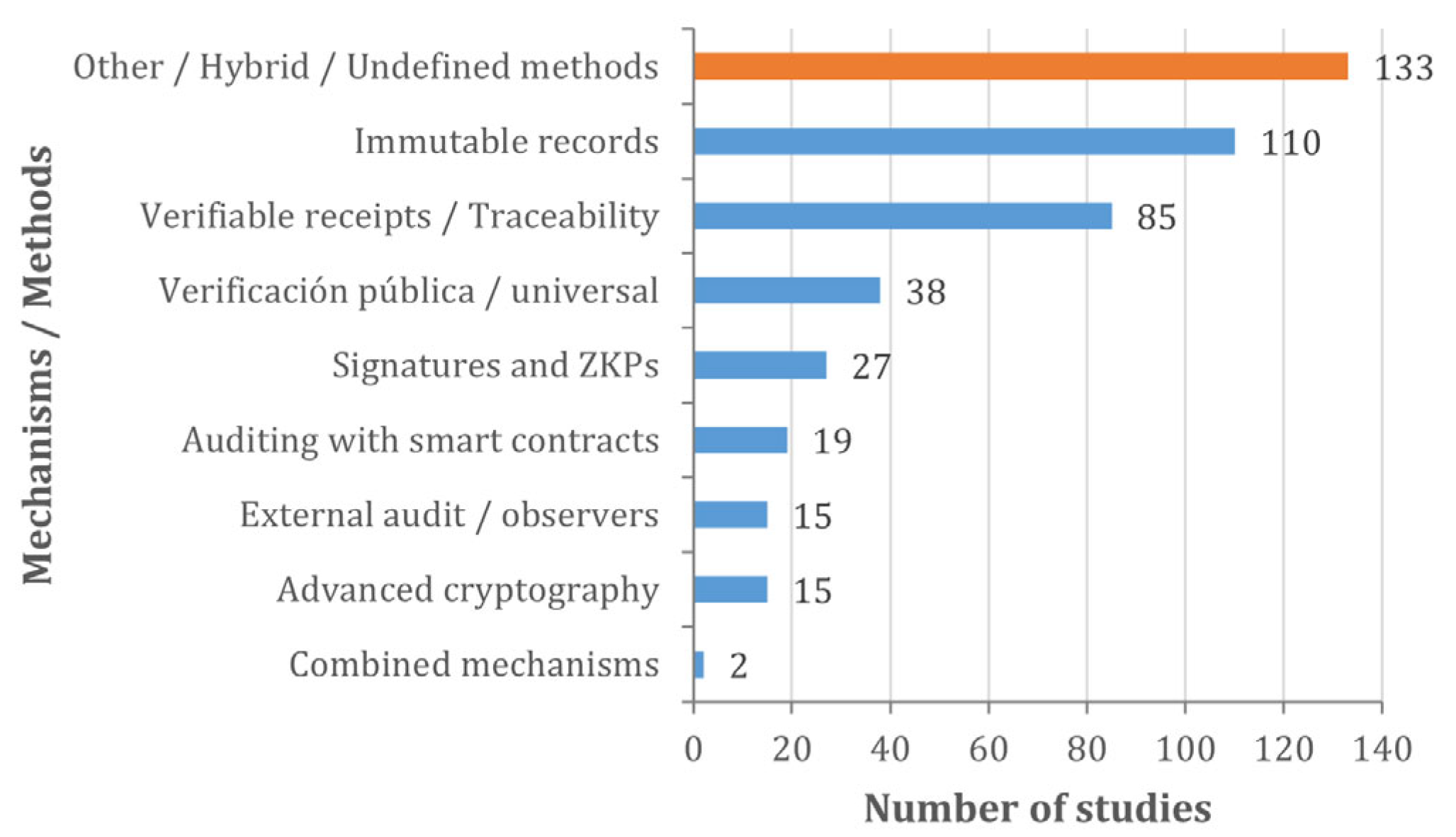

Figure 9 visually summarises the frequency with which the different verification and audit mechanisms or methods appear in the included primary studies, grouped into the following main categories:

Use of blockchain to ensure integrity and immutability (immutable records).

Auditing through smart contracts or code.

Automated public or universal verification (individual or results).

Use of digital signatures, ZKPs, blind signatures, ring signatures, or similar for authenticity and anonymity.

Use of verifiable receipt mechanisms or transparency with public traceability.

External auditing or observer roles to validate integrity.

Use of combined mechanisms (blockchain + biometrics, OTP, multiple factors).

Verification and validation using advanced cryptographic techniques (such as homomorphic encryption, zk-SNARKs, etc.).

The total number of studies in the graph (444) is the sum of mentions by category, not the number of unique studies (338). In other words, some studies appear in more than one category because they report on several verification and audit mechanisms/methods.

The graph provides a structured overview of the verification and auditing mechanisms and methods used in blockchain-based electronic voting systems, highlighting a clear preference for approaches focused on immutability, traceability, and public transparency as fundamental pillars for ensuring trust in electoral processes.

The most frequently represented mechanism is the use of “Other mechanisms” (133 studies), a category that includes specific non-standardised approaches, emerging techniques, or hybrid strategies still in the exploratory phase. Its high frequency indicates the evolving dynamics of the field, in which researchers are testing new forms of verification beyond conventional frameworks. The “Other” category also includes studies in which the mechanism/method is not directly related to the main categories but addresses alternative, insufficiently specified, or secondary techniques (e.g., administrative verifications, internal organisational methods); or, when a study does not mention any explicit mechanism/method.

This is followed by immutable records (110 studies), a native attribute of blockchain technologies, which ensures that recorded votes cannot be modified or deleted without leaving a trace. This technical principle has become the pillar of legitimacy for many proposals, providing a transparent and tamper-proof record.

Verifiable receipts and public traceability systems appear in 85 studies and allow voters to confirm that their vote was counted correctly without compromising anonymity. These mechanisms reinforce public confidence by allowing independent verification without relying on a central authority.

Public or universal verification (38 studies)—automated and accessible—further strengthens transparency by facilitating individual and collective audits of election results, making it a key feature in open democratic environments.

Cryptographic and technical signatures such as ZKPs (Zero-Knowledge Proofs), used in 27 studies, guarantee voter anonymity and authenticity, addressing two essential principles: privacy and security. These tools allow a transaction (vote) to be validated without revealing sensitive information, consolidating the value of blockchain in contexts of enhanced privacy.

Auditing through smart contracts (19 studies) is a significant innovation, as it enables automatic control and validation processes, reducing dependence on third parties. This automation provides efficiency and avoids potential human bias in electoral monitoring.

To a lesser extent, advanced cryptography mechanisms (15 studies) such as homomorphic encryption or zk-SNARKs are emerging, promising high levels of security but still facing technical challenges in scalability and implementation complexity. The same is true for external auditing or observers (15 studies), which, while providing institutional legitimacy, has been less addressed from a technical perspective.

Finally, combined mechanisms (only 2 studies) reflect limited attempts to integrate multiple approaches (such as blockchain + biometrics + OTP), possibly due to their technical complexity or high infrastructure requirements.

The current body of research reveals a consensus on the capacity of blockchain technology, supported by cryptographic techniques and decentralised verification mechanisms, to strengthen the integrity and auditing of electronic voting systems. However, research highlights the need for sustained empirical validation and solutions that ensure verifiability on a large scale and in real-world scenarios to consolidate social and institutional trust.

RQ6: How effective have real-world scenario tests been in validating scalable blockchain-based electronic voting systems?

The validation of scalable blockchain-based electronic voting systems in real-world scenarios is one of the most critical challenges and issues in recent literature. A synthesis of the primary studies that passed the quality assessment reveals that, although there is consensus on the disruptive potential of blockchain to ensure transparency, immutability, and verifiability of voting, systematic testing of its effectiveness in real environments remains limited and heterogeneous.

Predominantly, studies refer to testing in simulated contexts, pilot tests, or controlled deployments, while applications in large-scale real-world voting scenarios are scarce. For example, some studies did achieve implementations in university or institutional settings, where the systems were subjected to realistic functional conditions, obtaining promising results in terms of integrity and cost reduction compared to traditional processes [

35,

38]. However, in most proposals, experiments were confined to laboratories or proof-of-concept tests, without facing challenges inherent to complex environments, such as resistance to sustained attacks, population scalability, or large-scale anonymisation management.

A recurring pattern is the emphasis on auditability and automatic verification through smart contracts and immutable records, an aspect validated both in simulations and in small-scale real-world applications [

3,

54]. In scenarios where actual voting took place, improvements in participant confidence and transparency were observed, albeit with limitations in terms of anonymity and interoperability with conventional electoral processes.

There are notable differences in the scope and robustness of the tests. Some studies, such as those by Al-Maaitah et al. [

55] and Pereira et al. [

38], report empirical validation using real cases (university or national), showing that the technology is capable of withstanding public scrutiny and independent audits. In contrast, other studies, such as Marouan et al. [

14], even when applied in academic settings, are limited to simulations or semi-real tests, recognising that scalability and adaptation to massive national contexts still raise technical and political concerns. A significant contribution lies in those experiences that documented the process of gradual integration of the blockchain system before applying it to real contexts, emphasising the importance of institutional acceptance and digital literacy of participants [

42].

Although progress has been made in validating blockchain-based electronic voting systems in controlled settings and academic contexts, empirical evidence from large-scale real-world testing remains scarce. The field requires coordinated efforts that go beyond simulation and allow for rigorous assessment of the effectiveness, resilience, and social legitimacy of these systems under complex and diverse electoral conditions.