IALA: An Improved Artificial Lemming Algorithm for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Path Planning

Abstract

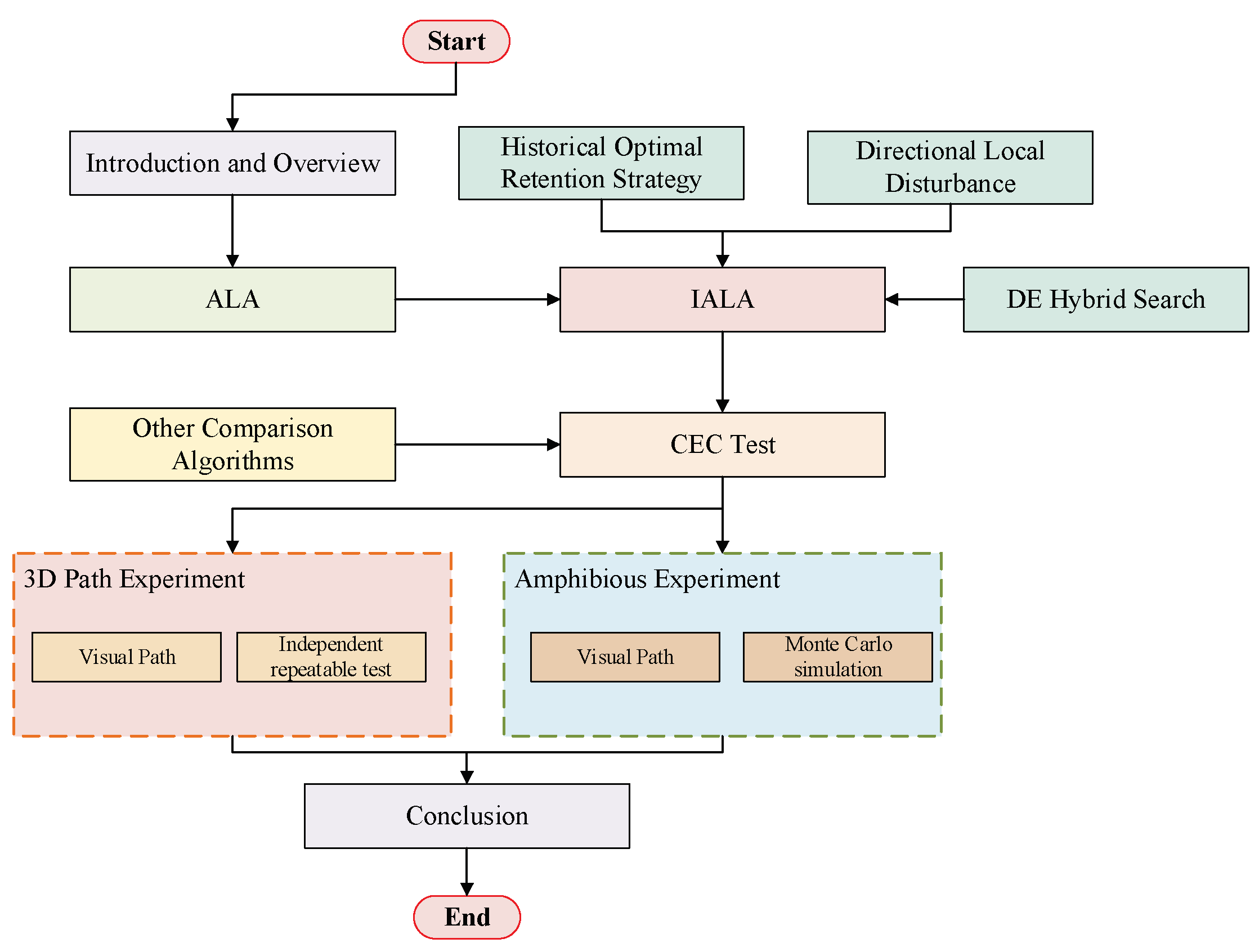

1. Introduction

- An Improved Artificial Lemming Algorithm (IALA) is proposed. On the basis of the original Artificial Lemming Algorithm (ALA), three improved strategies—Memory-based Learning Strategy, DE-hybrid Strategy, and directed neighborhood local search—are integrated to comprehensively enhance IALA’s ability to solve high-dimensional optimization problems and UAV path planning problems.

- Multi-dimensional repeated independent experiments are conducted to compare IALA with eight other state-of-the-art algorithms on the CEC2017 benchmark suite, so as to highlight the superiority of IALA. Wilcoxon rank-sum test and Friedman ranking analysis are employed to verify the significant differences between IALA and the comparative algorithms.

- IALA and the comparative algorithms are applied to an eight-scenario 3D UAV path planning model. Thirty independent experiments are repeated to compare the performance of IALA with other algorithms in engineering problems.

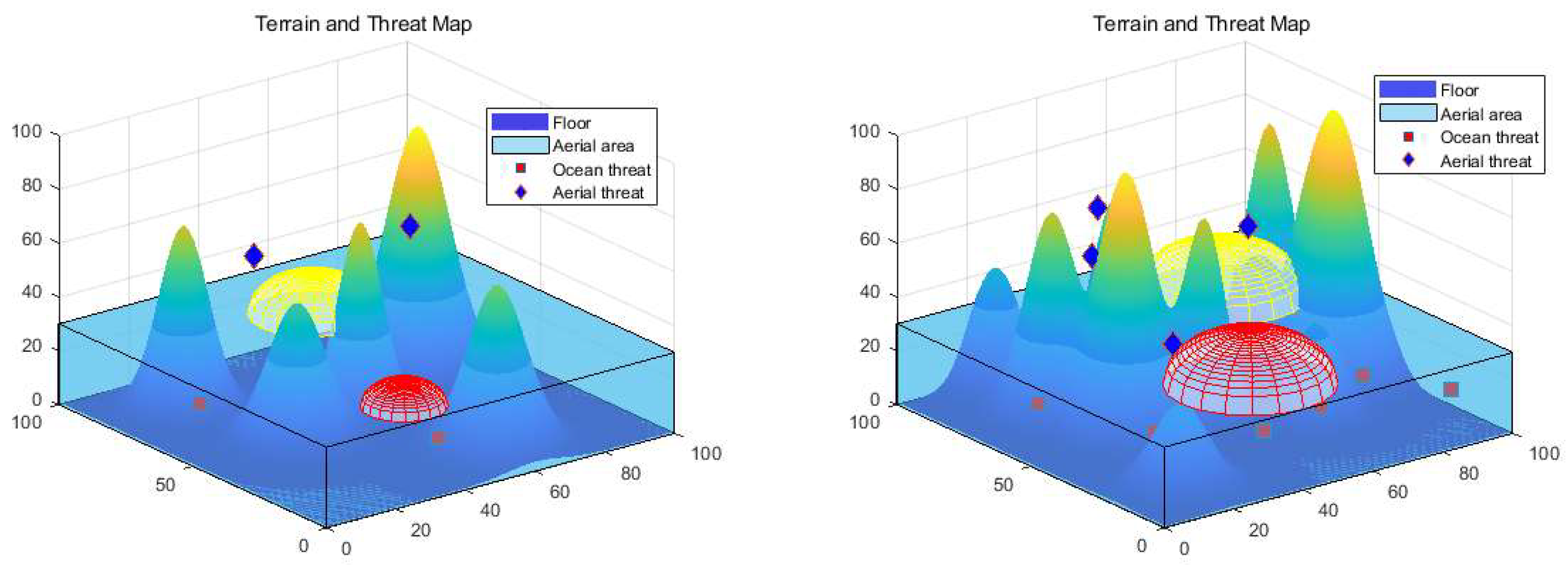

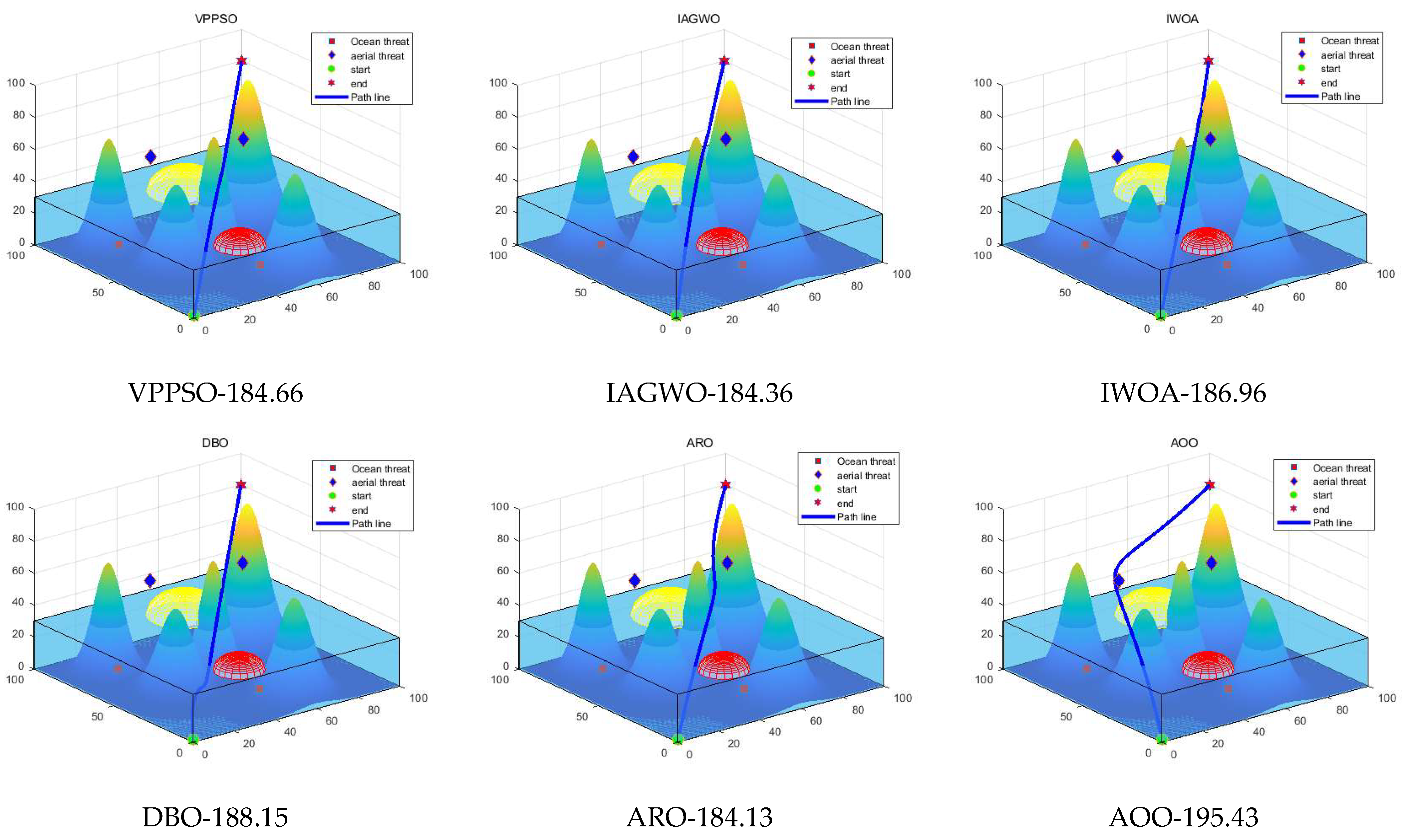

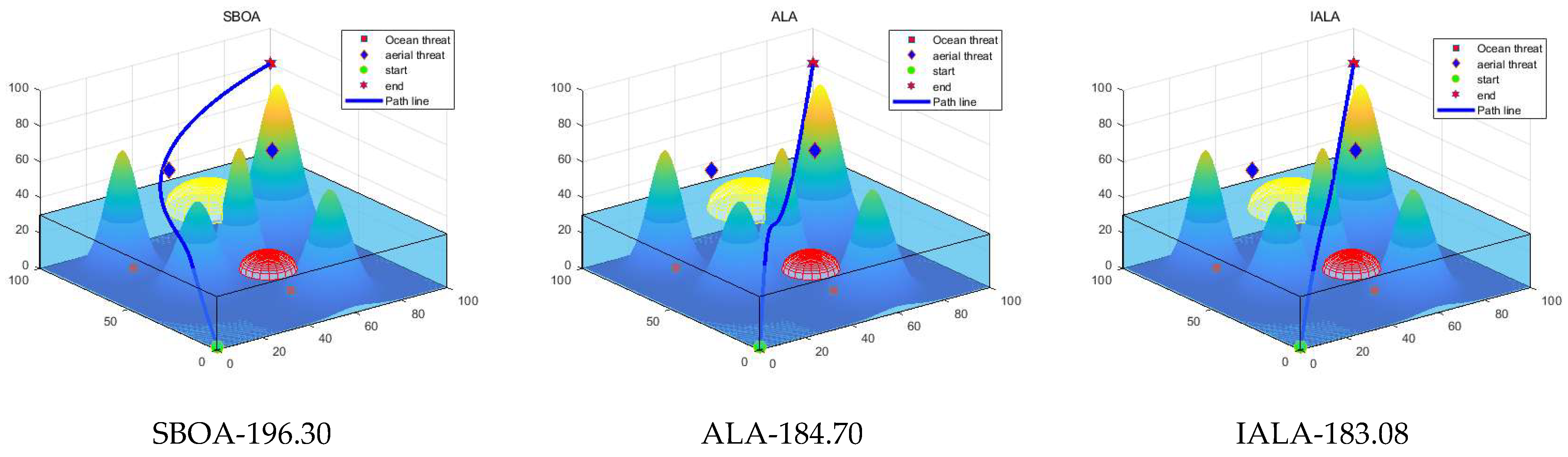

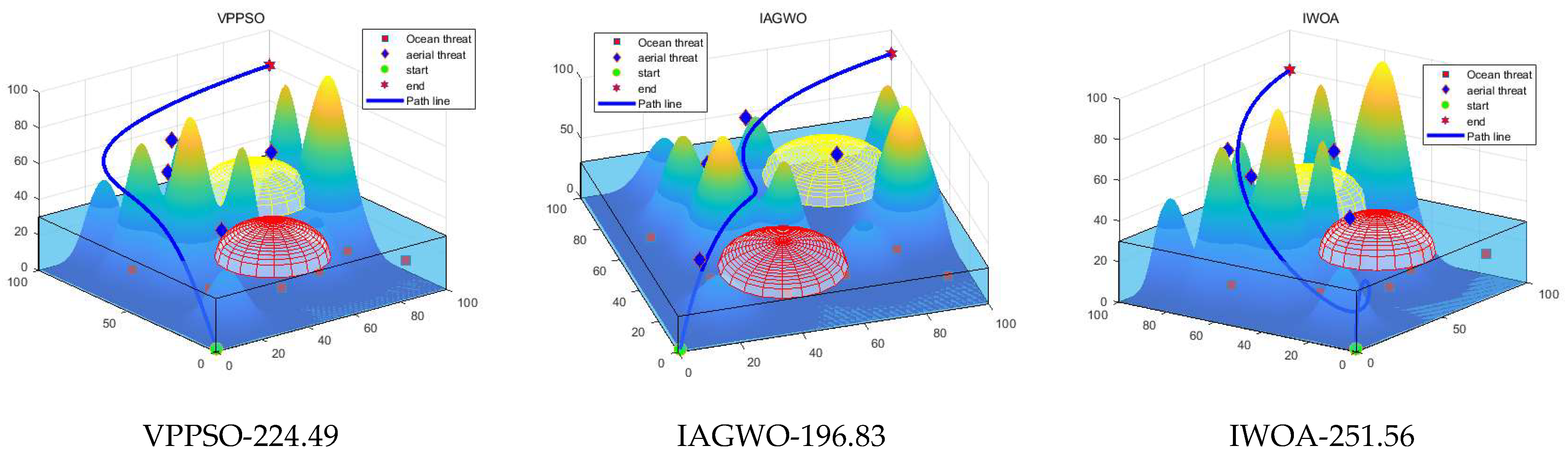

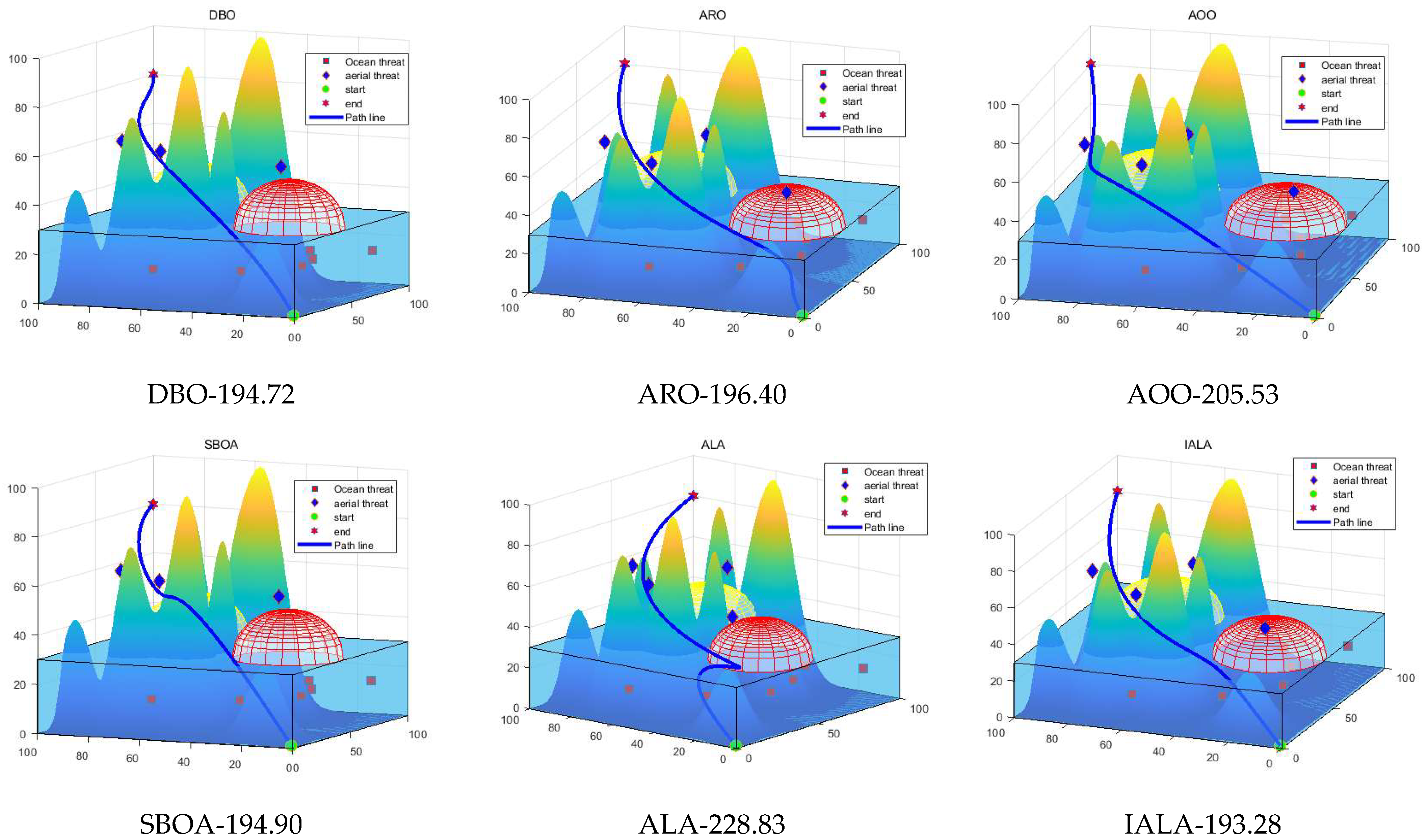

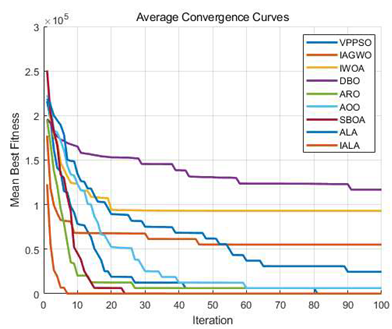

- An amphibious UAV path planning model is constructed, and IALA along with the other eight algorithms are applied to this model. The path planning results are analyzed through visual presentation. In addition, Monte Carlo simulations of the nine algorithms are performed in this scenario to evaluate the robustness of the algorithms.

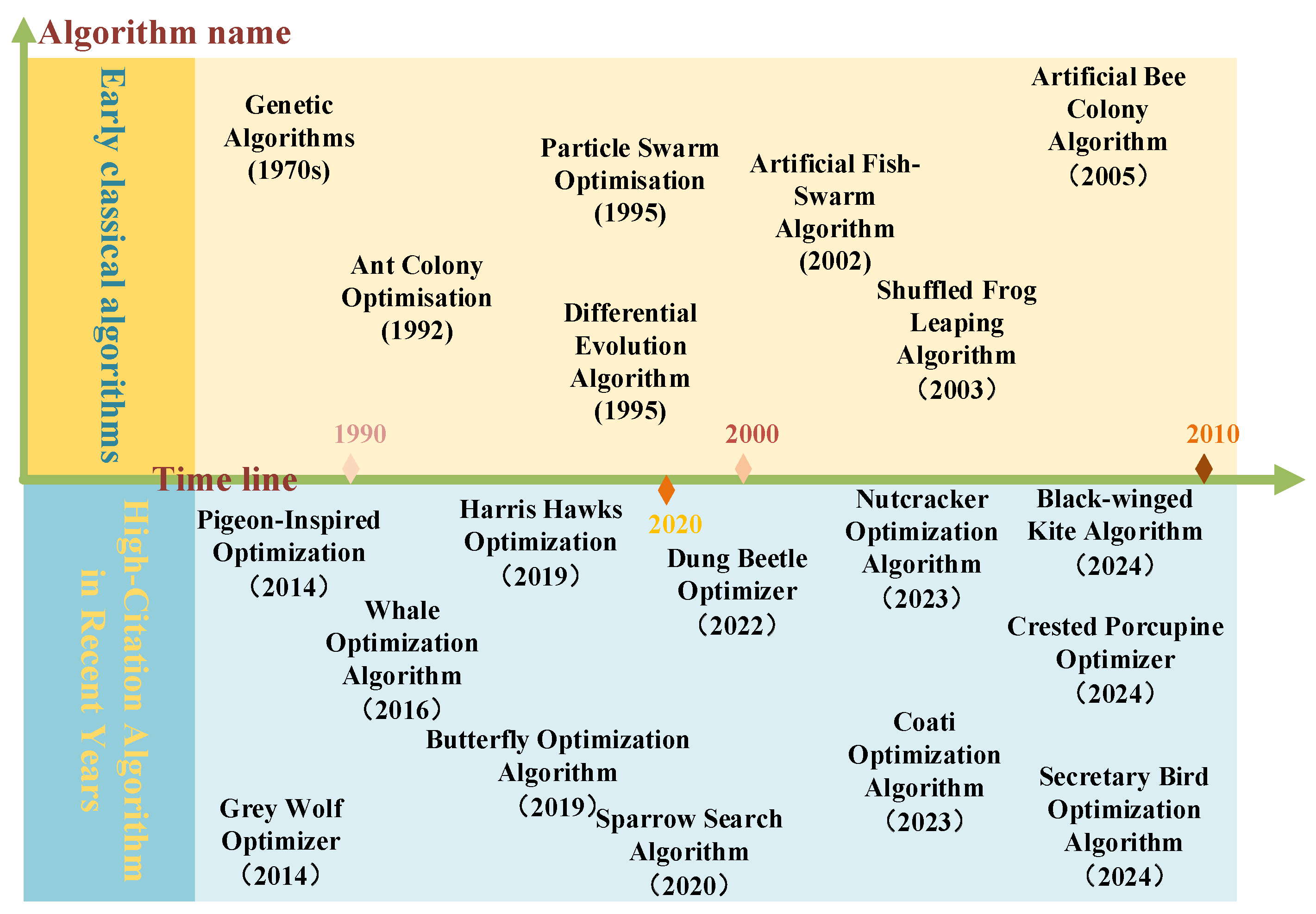

2. Literature Review

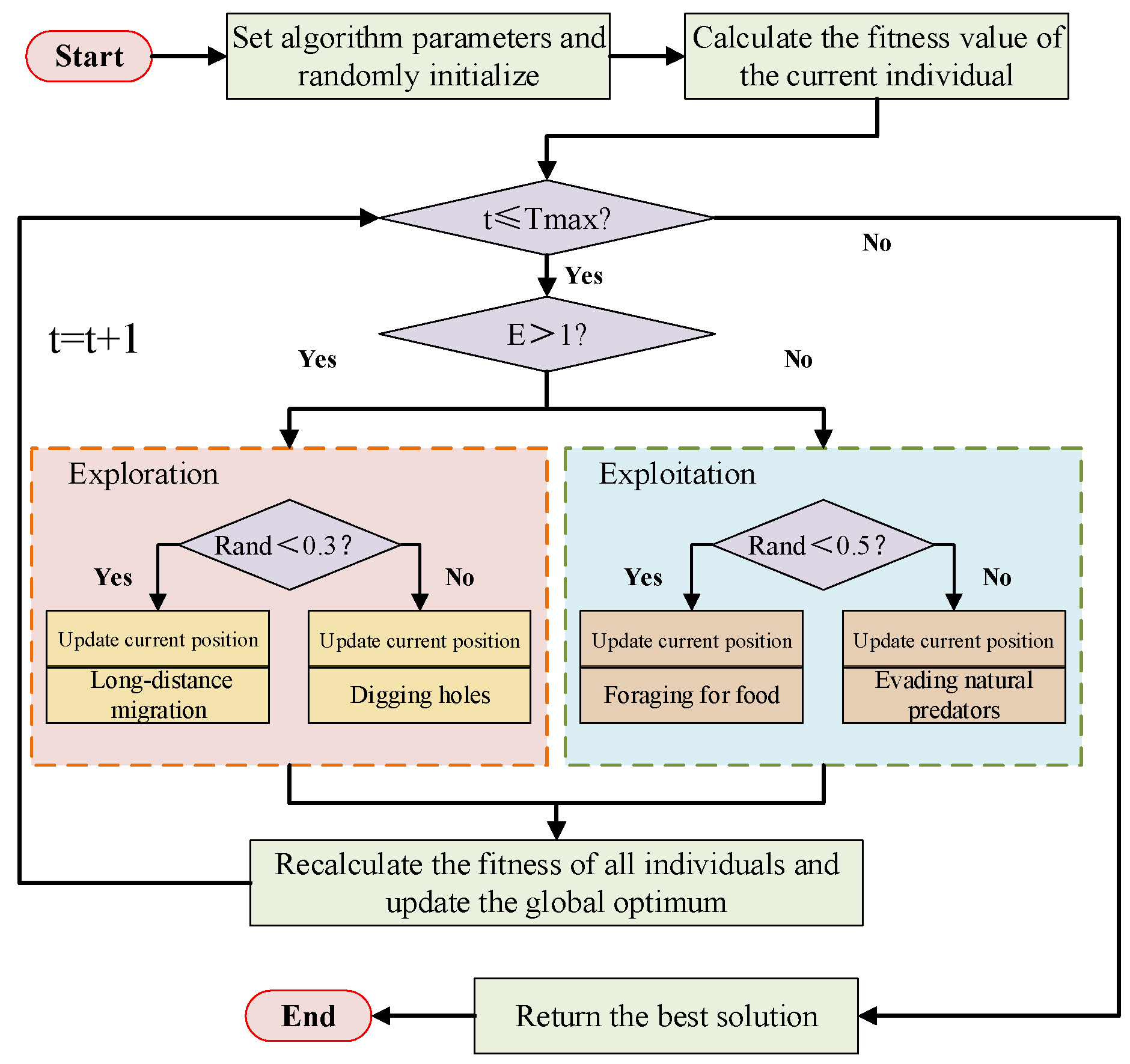

3. ALA Algorithm

3.1. Initialization

3.2. Long-Distance Migration (Exploration)

3.3. Digging Holes (Exploration)

3.4. Foraging (Exploitation)

3.5. Avoiding Predators (Exploitation)

3.6. Energy Mechanism

4. Proposed Algorithm

4.1. Optimal Information Retention Strategy Based on Individual Historical Memory

4.2. Hybrid Search Strategy Based on Differential Evolution Operator Fusion

4.3. Local Refined Search Strategy Based on Directed Neighborhood Perturbation

4.4. Pseudocode

| Algorithm 1: IALA (Improved Artificial Lemming Algorithm) |

| Input: max iterations: Tmax, population size: N, problem dimension: Dim Output: Optimal position: Z_best, fitness_best |

| 1. Initialize N individuals Zi (i = 1, …, N); 2. evaluate fitness; Set Zbest = arg min fitness; pbesti = Zi 3. While t ≤ Tmax do 4. Compute energy coefficient E(t), for each individual Zi do 5. If E > 1 then # Exploration phase 6. If rand < 0.3 then # Long-distance migration 7. update Zi 8. Else # Digging holes 9. update Zi 10. End If 11. Else # Exploitation phase 12. If rand < 0.5 then # Foraging 13. update Zi 14. Else # Predator avoidance 15. update Zi 16. End If 17. End If 18. Apply boundary control and greedy selection 19. Update pbesti if fitness (Zi) improves ▷ Strategy 1 20. End For 21. Apply DE operator: current-to-best mutation and crossover ▷ Strategy 2 22. Perform neighborhood directed local search on elite pbest set ▷ Strategy 3 23. Update Z_best from pbest library 24. t = t + 1 25. End While 26. return Z_best and fitness_best |

4.5. Complexity Analysis

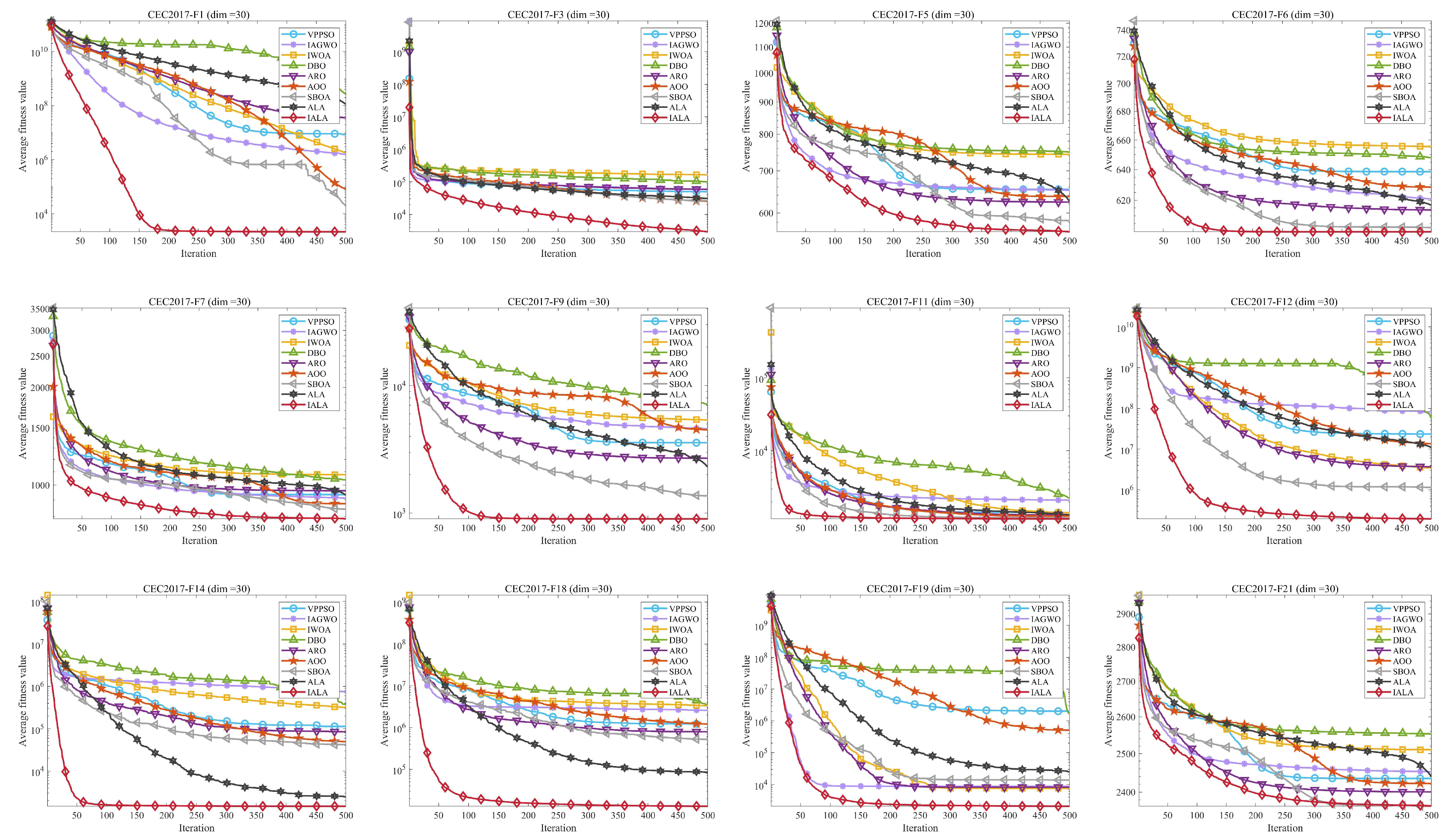

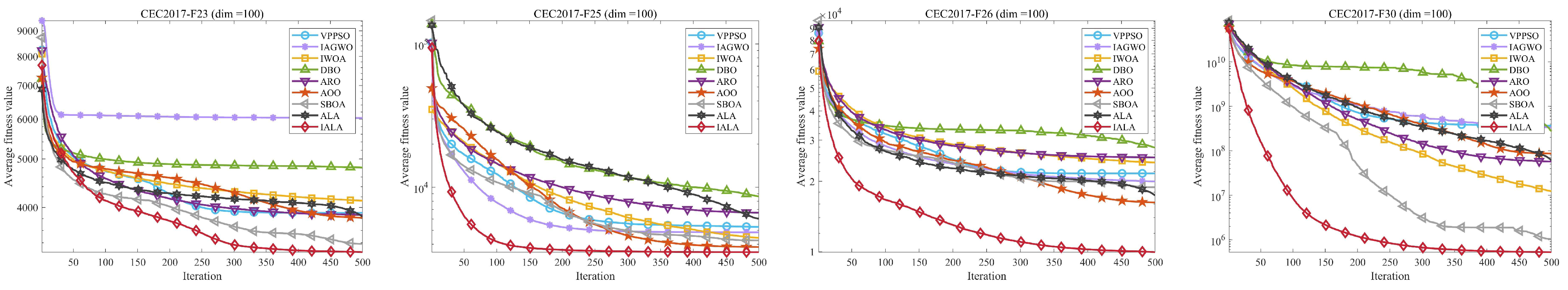

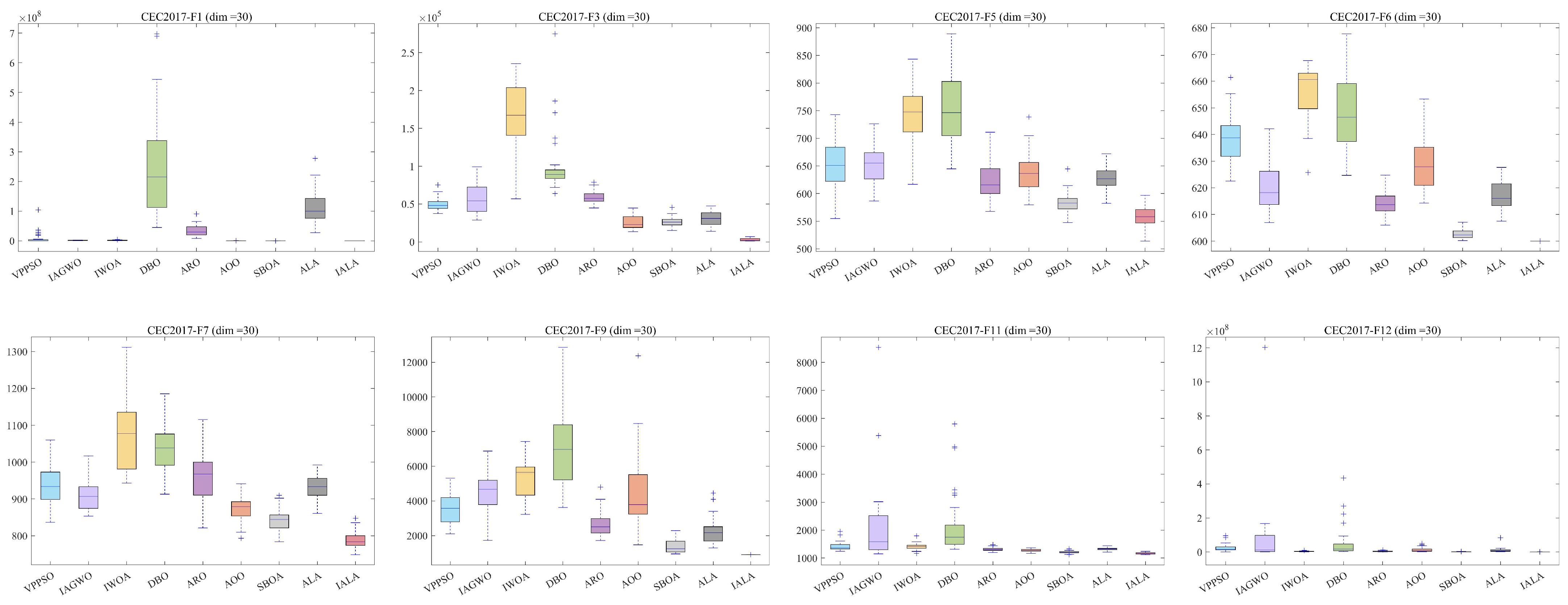

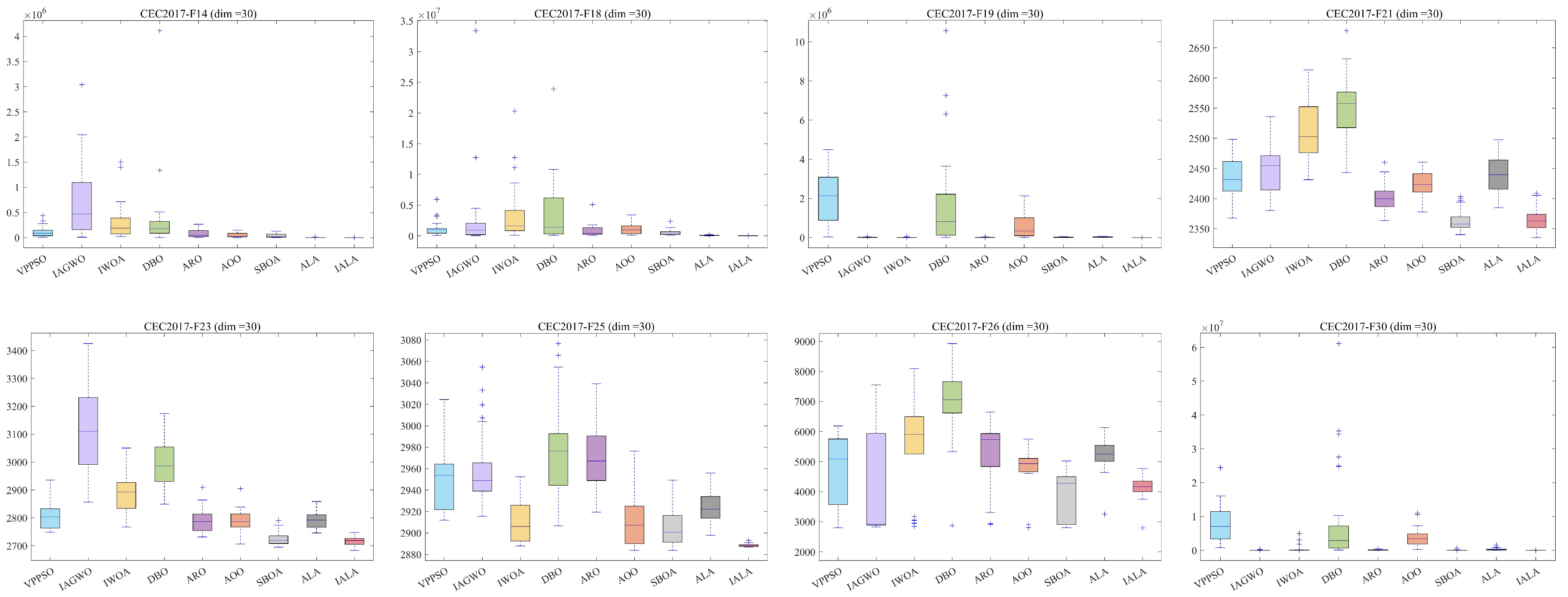

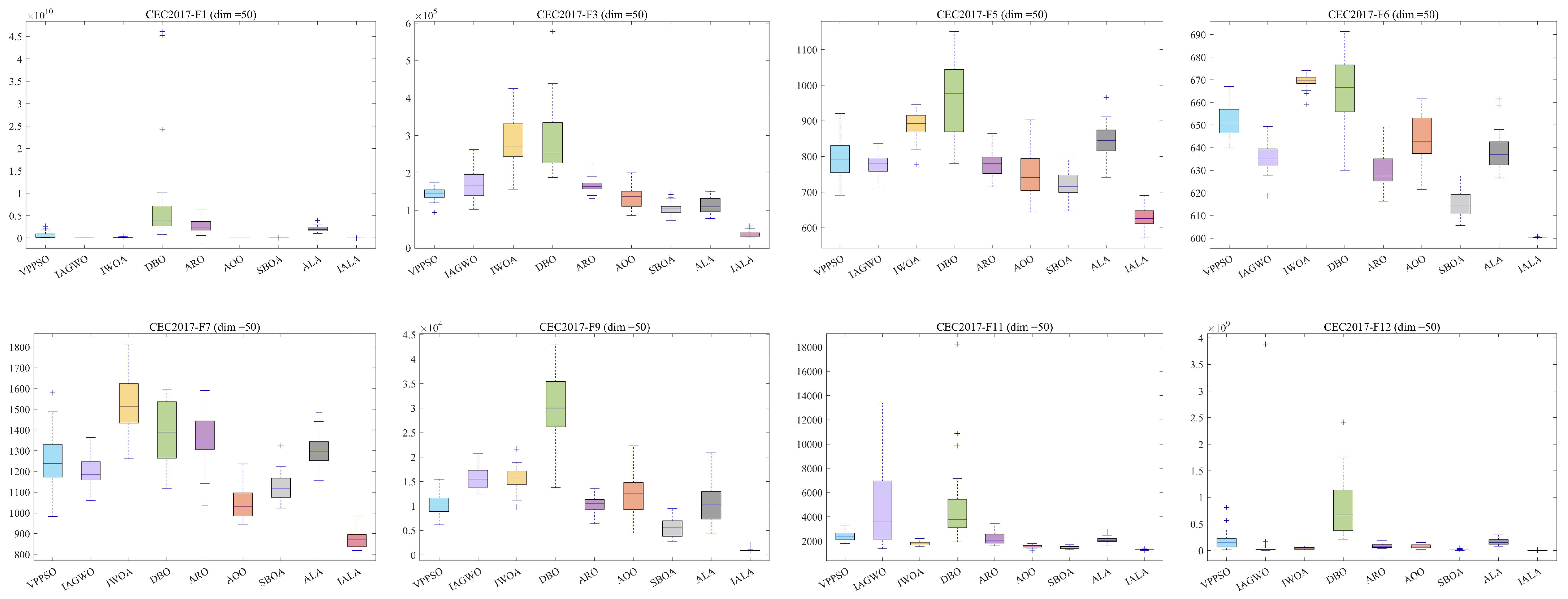

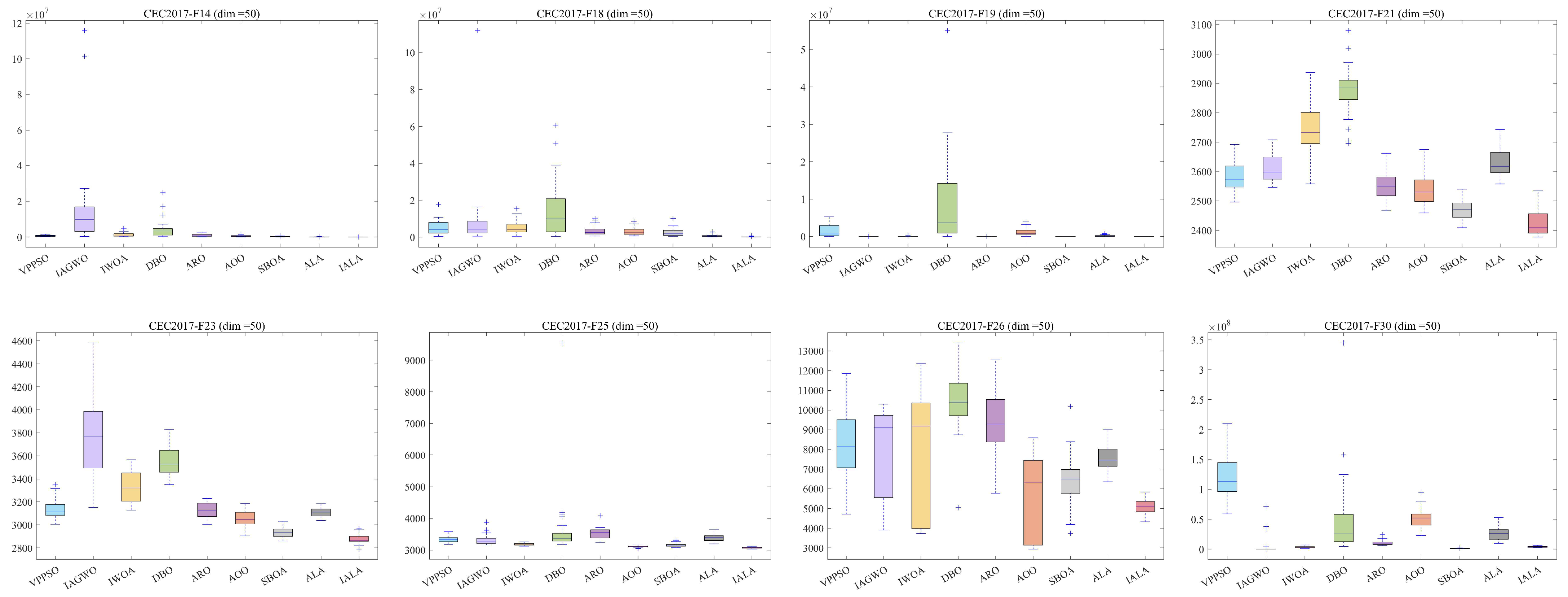

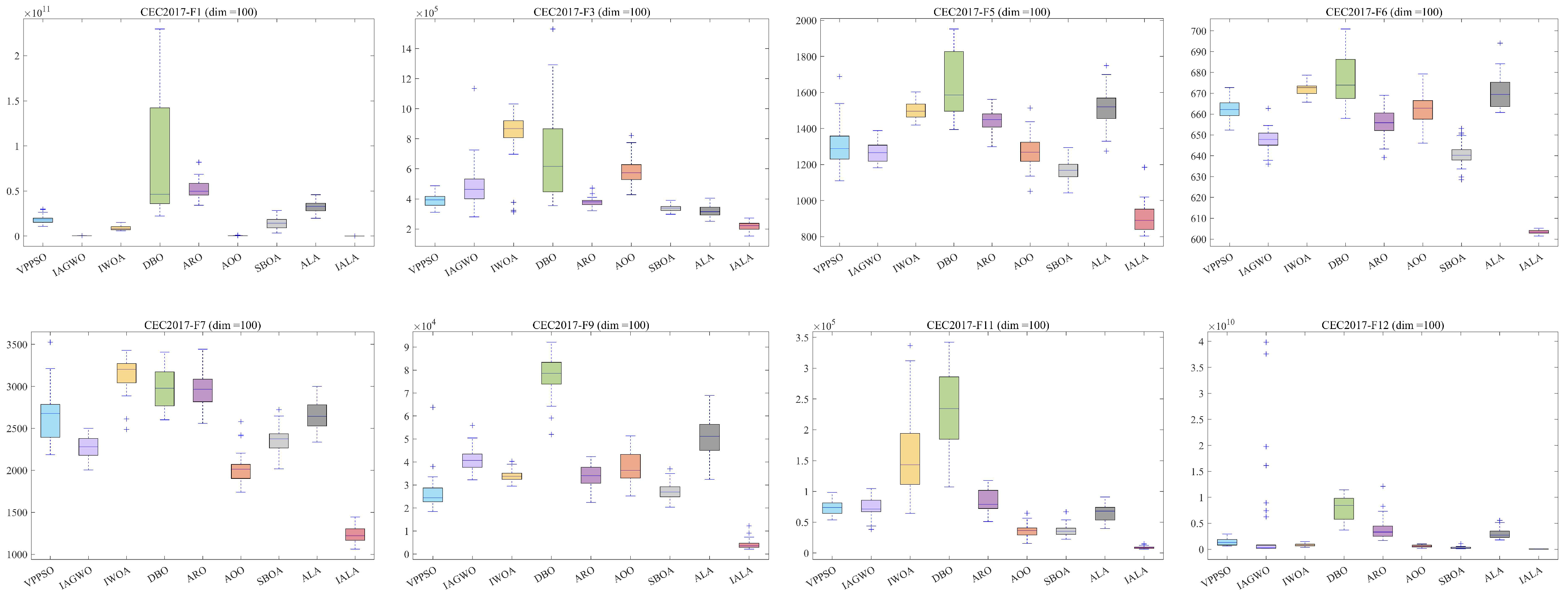

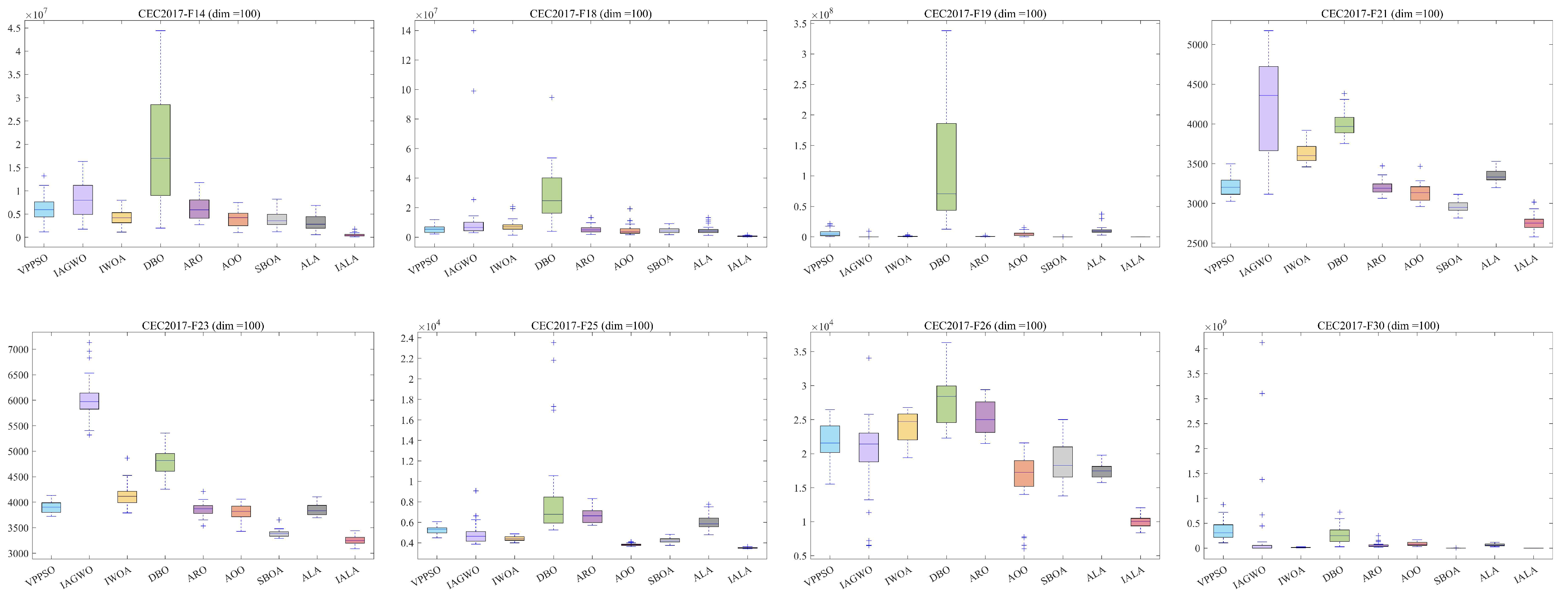

5. CEC2017 Test

5.1. Test Results and Analysis

5.2. Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test

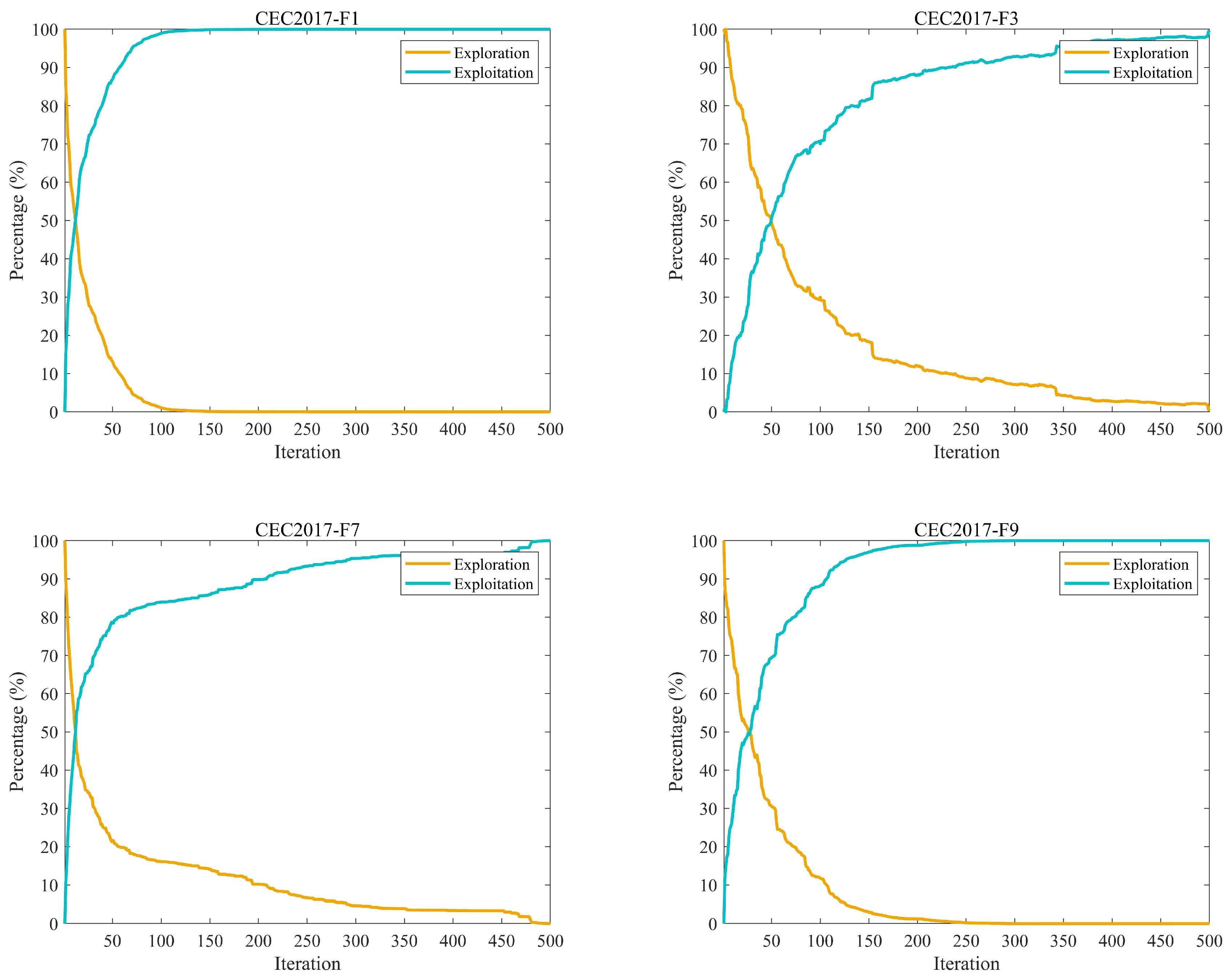

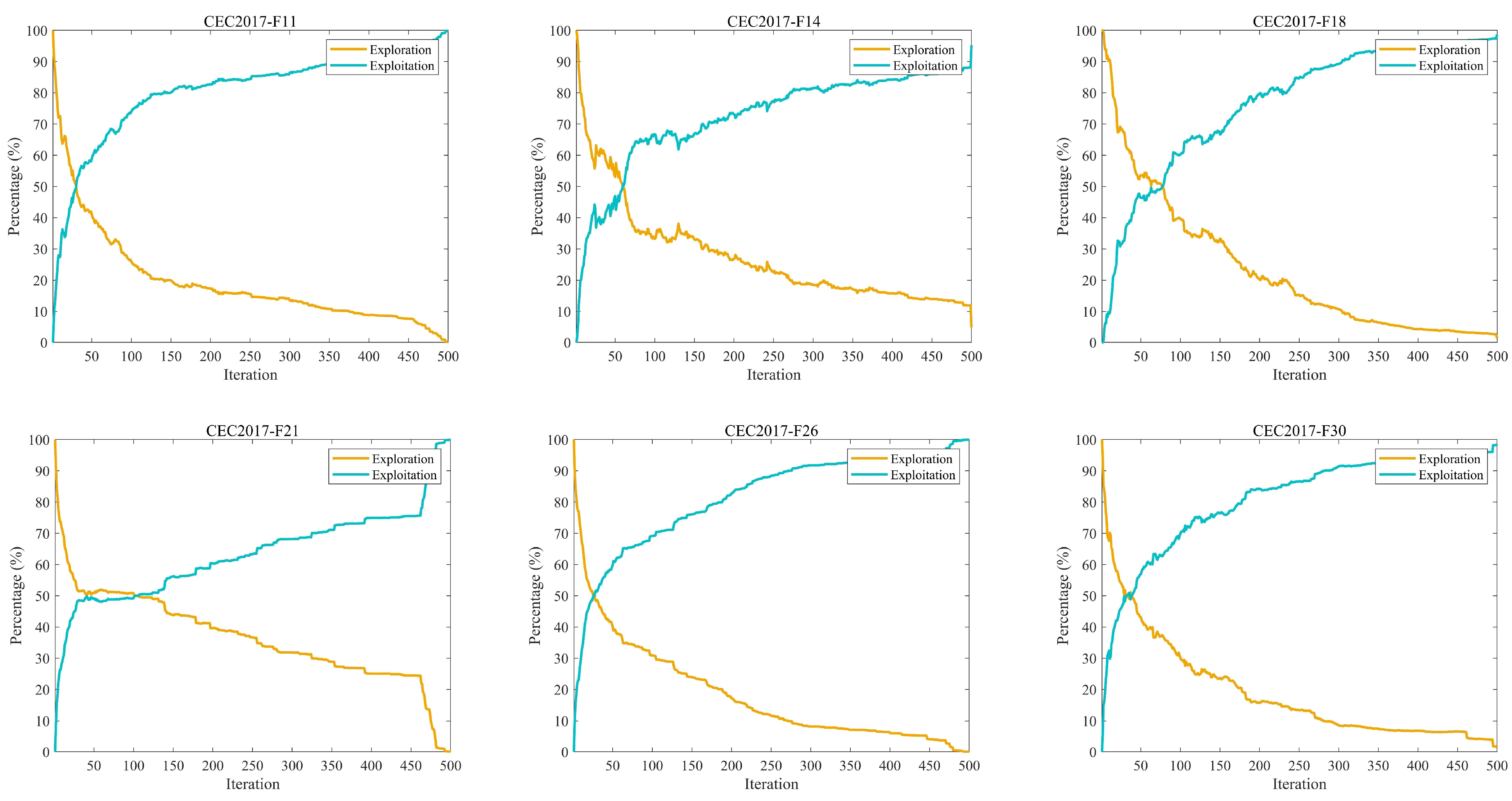

5.3. Exploration and Exploitation Analysis

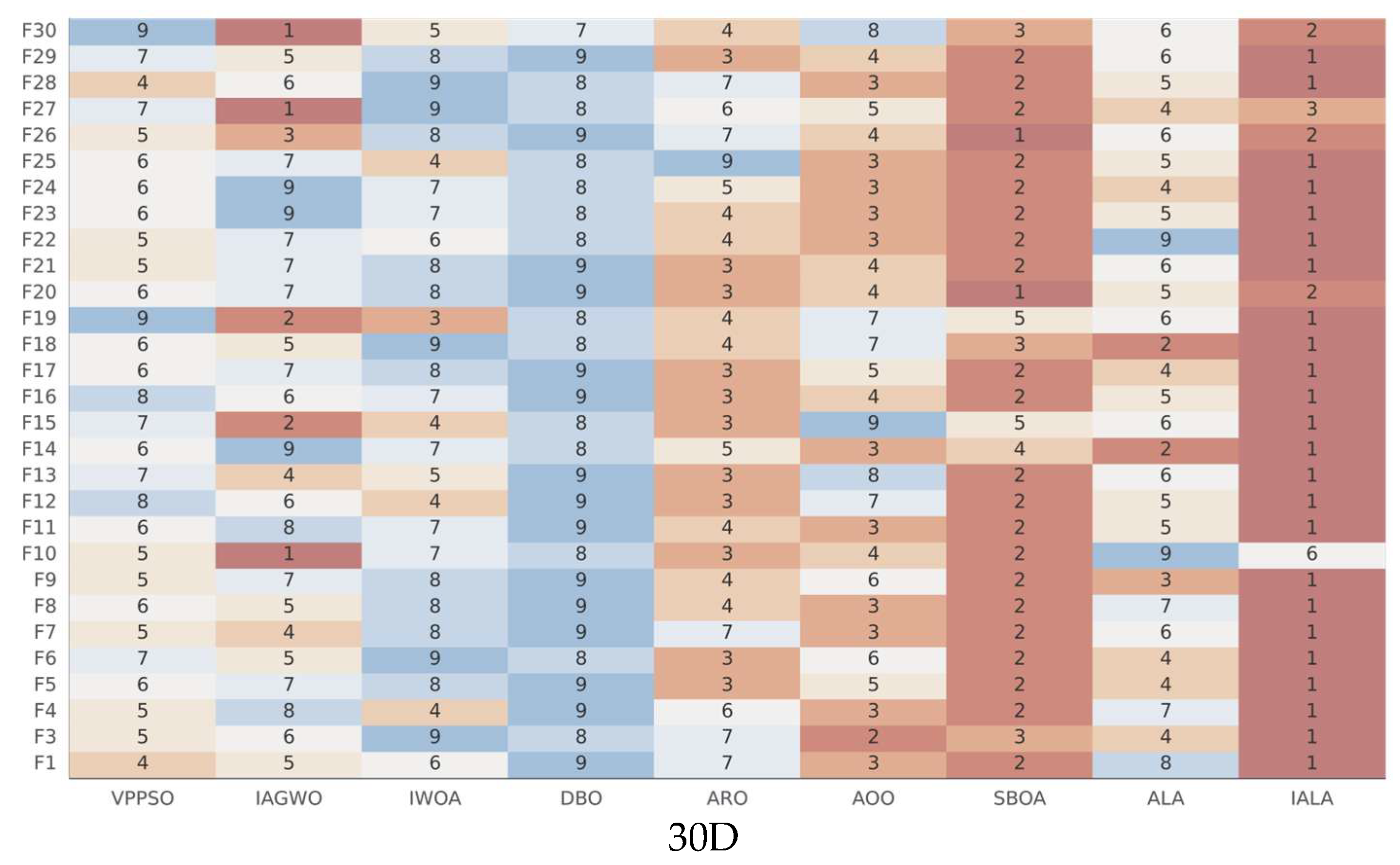

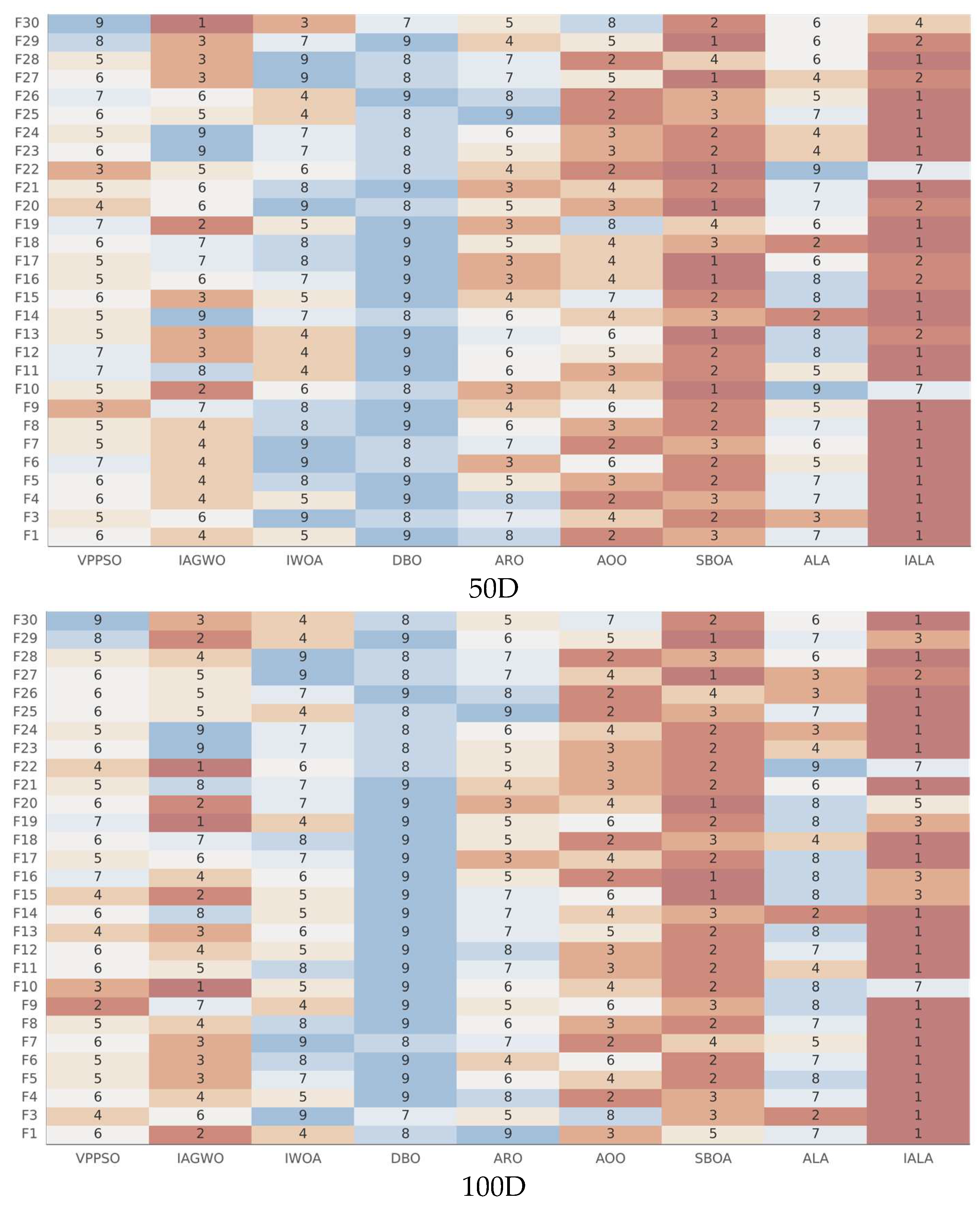

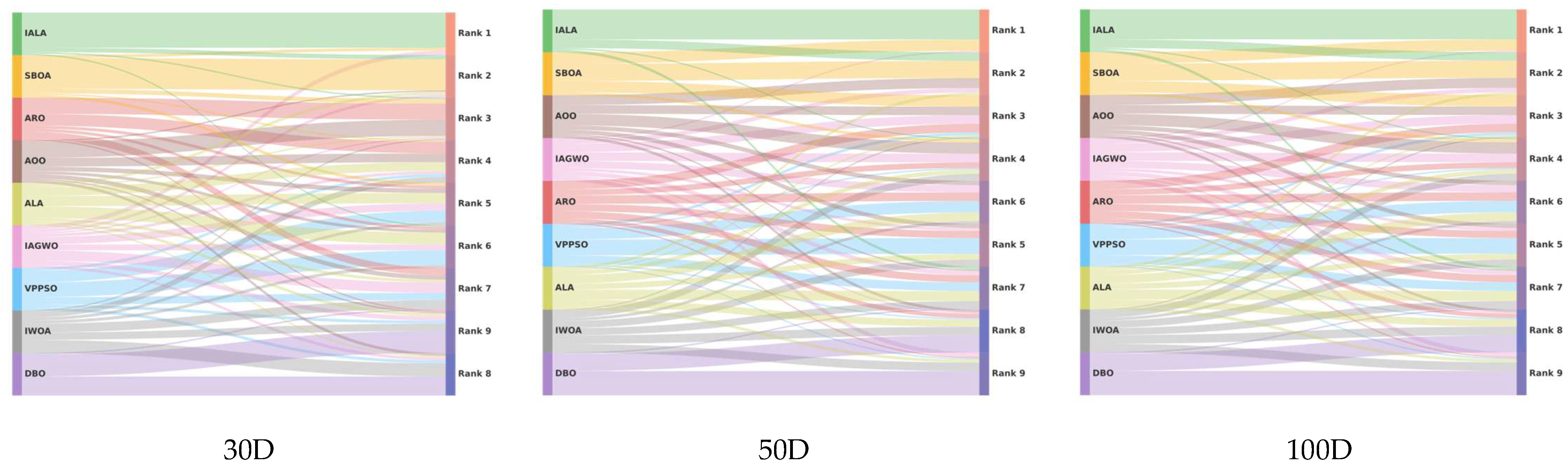

5.4. Friedman Ranking Analysis

6. Three-Dimensional Path Planning for UAV

6.1. Mathematical Model

6.2. Simulation Experiments and Discussion of Results

7. Path Planning for Amphibious UAVs

7.1. Mathematical Model

7.2. Simulation Experiments and Discussion of Results

8. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Jin, X.; Chen, H.; Yu, S. CLMGO: An enhanced Moss Growth Optimizer for complex engineering problems. Results Eng. 2025, 28, 108276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Liu, R.; Li, S. A novel improved dung beetle optimization algorithm for collaborative 3D path planning of UAVs. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J.M. Evolution or revolution? The rise of UAVs. IEEE Technol. Soc. Mag. 2006, 25, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunovjanek, M.; Wankmüller, C. Containing the COVID-19 pandemic with drones-Feasibility of a drone enabled back-up transport system. Transp. Policy 2021, 106, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benarbia, T.; Kyamakya, K. A literature review of drone-based package delivery logistics systems and their implementation feasibility. Sustainability 2021, 14, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, S.; Ju, C.; Son, H.I. Unmanned aerial vehicles in agriculture: A review of perspective of platform, control, and applications. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 105100–105115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndlovu, H.S.; Odindi, J.; Sibanda, M.; Mutanga, O. A systematic review on the application of UAV-based thermal remote sensing for assessing and monitoring crop water status in crop farming systems. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2024, 45, 4923–4960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Yu, X.; Dedman, S.; Rosso, M.; Zhu, J.; Yang, J.; Xia, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, G.; Wang, J. UAV remote sensing applications in marine monitoring: Knowledge visualization and review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 155939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, S.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, G. A review on UAV-based remote sensing technologies for construction and civil applications. Drones 2022, 6, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Jiang, Z.; Sun, R.; Cheng, N.; Feng, H. Maritime search and rescue based on group mobile computing for unmanned aerial vehicles and unmanned surface vehicles. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 16, 7700–7708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, D.; Hawary, A.F.; Ramdan, M.I.; Alvarez, F.V.; Gonzalez, F. QuickNav: An effective collision avoidance and path-planning algorithm for UAS. Drones 2023, 7, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehadeh, M.A.; Kůdela, J. Benchmarking global optimization techniques for unmanned aerial vehicle path planning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 293, 128645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Mulvaney, D.; Sillitoe, I.; Swere, E. Robot navigation by waypoints. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2008, 52, 175–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, R.A.; Omri, M.; Abdel-Khalek, S.; Ali, E.S.; Alotaibi, M.F. Optimal path planning for drones based on swarm intelligence algorithm. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 34, 10133–10155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos, A.; Cruz-Reyes, L.; Fernández, E.; Rivera, G.; Gomez-Santillan, C.; Rangel-Valdez, N. Hybridisation of swarm intelligence algorithms with multi-criteria ordinal classification: A strategy to address many-objective optimisation. Mathematics 2022, 10, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.E. Genetic Algorithms in Search, Optimization, and Machine Learning; Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.: Boston, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Dorigo, M.; Colorni, A.; Maniezzo, V. Distributed optimization by ant colonies. In Proceedings of the First European Conference on Artificial Life, Paris, France, 11–13 December 1991; pp. 134–142. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhart, R.; Kennedy, J. A new optimizer using particle swarm theory. In MHS’95, Proceedings of the Sixth International Symposium on Micro Machine and Human Science, Nagoya, Japan, 4–6 October 1995; IEEE: New York, NT, USA, 1995; pp. 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Storn, R.; Price, K. Differential evolution–a simple and efficient heuristic for global optimization over continuous spaces. J. Glob. Optim. 1997, 11, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaboga, D.; Basturk, B. On the performance of artificial bee colony (ABC) algorithm. Appl. Soft Comput. 2008, 8, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Shen, B. A novel swarm intelligence optimization approach: Sparrow search algorithm. Syst. Sci. Control Eng. 2020, 8, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, M.; Montazeri, Z.; Trojovská, E.; Trojovský, P. Coati Optimization Algorithm: A new bio-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for solving optimization problems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 259, 110011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Singh, S. Butterfly optimization algorithm: A novel approach for global optimization. Soft Comput. 2019, 23, 715–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Li, G.; Meng, Z. Beluga whale optimization: A novel nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 251, 109215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Qiao, P. Pigeon-inspired optimization: A new swarm intelligence optimizer for air robot path planning. Int. J. Intell. Comput. Cybern. 2014, 7, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Basset, M.; Mohamed, R.; Jameel, M.; Abouhawwash, M. Nutcracker optimizer: A novel nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for global optimization and engineering design problems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 262, 110248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, H.; Wang, M.; Heidari, A.A.; Mirjalili, S. Slime mould algorithm: A new method for stochastic optimization. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 111, 300–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faramarzi, A.; Heidarinejad, M.; Mirjalili, S.; Gandomi, A.H. Marine Predators Algorithm: A nature-inspired metaheuristic. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 152, 113377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahzadeh, B.; Soleimanian Gharehchopogh, F.; Mirjalili, S. Artificial gorilla troops optimizer: A new nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for global optimization problems. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2021, 36, 5887–5958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Mirjalili, S.M.; Lewis, A. Grey wolf optimizer. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2014, 69, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, A.A.; Mirjalili, S.; Faris, H.; Aljarah, I.; Mafarja, M.; Chen, H. Harris hawks optimization: Algorithm and applications. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 97, 849–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, W.C.; Hu, X.X.; Qiu, L.; Zang, H.F. Black-winged kite algorithm: A nature-inspired meta-heuristic for solving benchmark functions and engineering problems. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Basset, M.; Mohamed, R.; Abouhawwash, M. Crested Porcupine Optimizer: A new nature-inspired metaheuristic. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 284, 111257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Zhao, D.; Heidari, A.A.; Liu, L.; Chen, Y.; Chen, H. Polar lights optimizer: Algorithm and applications in image segmentation and feature selection. Neurocomputing 2024, 607, 128427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Lewis, A. The whale optimization algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2016, 95, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, D.; Poyatos, J.; Ser, J.D.; García, S.; Hussain, A.; Herrera, F. Comprehensive taxonomies of nature-and bio-inspired optimization: Inspiration versus algorithmic behavior, critical analysis recommendations. Cogn. Comput. 2020, 12, 897–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mande, S.S.; Srinivasulu, M.; Anand, S.; Anuradha, K.; Tiwari, M.; Esakkiammal, U. Swarm Intelligence Algorithms for Optimization Problems a Survey of Recent Advances and Applications. ITM Web Conf. 2025, 76, 05008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpert, D.H.; Macready, W.G. No free lunch theorems for optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 1, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Ding, Q. Analysing the dynamics of digital chaotic maps via a new period search algorithm. Nonlinear Dyn. 2019, 97, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, J.; Chen, J.; Liu, Z. An adaptive lion swarm optimization algorithm incorporating tent chaotic search and information entropy. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2023, 16, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Cai, Y.; Tang, D.; Chen, W.; Hu, L. Memetic quantum optimization algorithm with levy flight for high dimension function optimization. Appl. Intell. 2022, 52, 17922–17940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, S.; Mohapatra, P. Fast random opposition-based learning Golden Jackal Optimization algorithm. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 275, 110679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Liu, R.; Liu, X. Simulation Application of Adaptive Strategy Hybrid Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm in Multi-UAV 3D Path Planning. Computers 2025, 14, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Cui, H.; Khurma, R.A.; Castillo, P.A. Artificial lemming algorithm: A novel bionic meta-heuristic technique for solving real-world engineering optimization problems. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shami, T.M.; Mirjalili, S.; Al-Eryani, Y.; Daoudi, K.; Izadi, S.; Abualigah, L. Velocity pausing particle swarm optimization: A novel variant for global optimization. Neural Comput. Appl. 2023, 35, 9193–9223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Xu, J.; Liang, W.; Qiu, Y.; Bao, S.; Tang, L. Improved multi-strategy adaptive Grey Wolf Optimization for practical engineering applications and high-dimensional problem solving. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Liu, D.; Fu, Y.; Chen, J.; He, L.; Yan, J.; Yang, D. Prediction of Self-Care Behaviors in Patients Using High-Density Surface Electromyography Signals and an Improved Whale Optimization Algorithm-Based LSTM Model. J. Bionic Eng. 2025, 22, 1963–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Shen, B. Dung beetle optimizer: A new meta-heuristic algorithm for global optimization. J. Supercomput. 2023, 79, 7305–7336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cao, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Mirjalili, S.; Zhao, W. Artificial rabbits optimization: A new bio-inspired meta-heuristic algorithm for solving engineering optimization problems. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 114, 105082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.B.; Hu, R.B.; Geng, F.D.; Xu, L.; Chu, S.C.; Pan, J.S.; Meng, Z.-Y.; Mirjalili, S. The Animated Oat Optimization Algorithm: A nature-inspired metaheuristic for engineering optimization and a case study on Wireless Sensor Networks. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 318, 113589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Liu, D.; Chen, J.; He, L. Secretary bird optimization algorithm: A new metaheuristic for solving global optimization problems. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-González, O.; Targui, B.; Valencia-Palomo, G.; Guerrero-Sánchez, M.E. Robust cascade observer for a disturbance unmanned aerial vehicle carrying a load under multiple time-varying delays and uncertainties. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2024, 55, 1056–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbina-Brito, N.; Guerrero-Sánchez, M.E.; Valencia-Palomo, G.; Hernández-González, O.; López-Estrada, F.R.; Hoyo-Montaño, J.A. A predictive control strategy for aerial payload transportation with an unmanned aerial vehicle. Mathematics 2021, 9, 1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classification | Name | Year | Advantage | Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary Algorithm | GA | 1975 | Strong global search capability, clear underlying principles, and easy integration with other algorithms | Slow convergence speed, prone to getting stuck in local optima, high randomness in results, and complex parameter tuning |

| DE | 1996 | Simple structure, fast convergence speed, strong robustness, excels at handling continuous-space optimization problems | Prone to premature convergence, performance degrades in high-dimensional complex problems, sensitive to variation strategies and parameter selection | |

| Physical Heuristic Algorithm | SA | 1983 | Good global convergence, simple structure, effectively escapes local optima | Slow convergence speed, cooling strategy significantly impacts performance, solution accuracy is sometimes insufficient |

| MSO | 2025 | Dual-strategy synergy, efficient search, minimal parameters | Dependent on initial distribution, late-stage convergence oscillations, computational complexity | |

| TOA | 2025 | Precise local adjustments, intuitive algorithmic workflow, minimal control parameters, easy to understand and implement | Optimization results heavily depend on the quality of the initial solution, excessive focus on local optimization, limited global exploration capability | |

| DOA | 2025 | Unique balancing mechanism with a simple core system that is easy to implement | Requires initial accumulation of experience and exhibits slow convergence | |

| Swarm Intelligence Algorithm | PSO | 1995 | Simple concept, few parameters, fast convergence, easy to implement | Prone to local optima, low convergence accuracy in later stages, prone to oscillation |

| ACO | 1991 | Excels at discrete combinatorial optimization with fast convergence. | Computational time-consuming, prone to premature convergence, and sensitive to initial parameters. | |

| CPO | 2024 | Simple structure, few parameters, easy to implement and adjust | Leading competitive strategies may lead to population instability | |

| GO | 2024 | Fast convergence speed, high precision, and high adaptability | Parameter adjustments significantly impact performance | |

| HSO | 2025 | Global information search, escaping local optima with strong convergence accuracy | High computational complexity, convergence stability requires improvement |

| VPPSO | IAGWO | IWOA | DBO | ARO | AOO | SBOA | ALA | IALA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | F1 | 8.38 × 106 | 1.56 × 106 | 1.70 × 106 | 2.59 × 108 | 3.55 × 107 | 7.99 × 104 | 2.18 × 104 | 1.16 × 108 | 2.16 × 103 |

| F3 | 4.96 × 104 | 5.87 × 104 | 1.65 × 105 | 1.02 × 105 | 5.91 × 104 | 2.52 × 104 | 2.66 × 104 | 3.10 × 104 | 2.93 × 103 | |

| F4 | 5.32 × 102 | 6.43 × 102 | 5.22 × 102 | 7.01 × 102 | 5.50 × 102 | 5.08 × 102 | 5.05 × 102 | 5.64 × 102 | 5.03 × 102 | |

| F5 | 6.54 × 102 | 6.52 × 102 | 7.43 × 102 | 7.49 × 102 | 6.24 × 102 | 6.37 × 102 | 5.84 × 102 | 6.28 × 102 | 5.60 × 102 | |

| F6 | 6.39 × 102 | 6.21 × 102 | 6.56 × 102 | 6.48 × 102 | 6.14 × 102 | 6.28 × 102 | 6.03 × 102 | 6.17 × 102 | 6.00 × 102 | |

| F7 | 9.35 × 102 | 9.11 × 102 | 1.08 × 103 | 1.04 × 103 | 9.61 × 102 | 8.76 × 102 | 8.43 × 102 | 9.33 × 102 | 7.87 × 102 | |

| F8 | 9.28 × 102 | 9.20 × 102 | 9.80 × 102 | 1.01 × 103 | 9.07 × 102 | 8.98 × 102 | 8.80 × 102 | 9.30 × 102 | 8.65 × 102 | |

| F9 | 3.56 × 103 | 4.58 × 103 | 5.37 × 103 | 7.10 × 103 | 2.69 × 103 | 4.49 × 103 | 1.37 × 103 | 2.31 × 103 | 9.01 × 102 | |

| F10 | 4.82 × 103 | 4.39 × 103 | 5.81 × 103 | 6.59 × 103 | 4.54 × 103 | 4.78 × 103 | 4.40 × 103 | 6.30 × 103 | 5.15 × 103 | |

| F11 | 1.43 × 103 | 2.11 × 103 | 1.42 × 103 | 2.25 × 103 | 1.31 × 103 | 1.28 × 103 | 1.21 × 103 | 1.33 × 103 | 1.17 × 103 | |

| F12 | 2.34 × 107 | 8.12 × 107 | 3.41 × 106 | 5.67 × 107 | 3.67 × 106 | 1.35 × 107 | 1.14 × 106 | 1.10 × 107 | 1.94 × 105 | |

| F13 | 9.88 × 104 | 2.51 × 107 | 4.60 × 104 | 8.23 × 106 | 1.65 × 104 | 1.39 × 105 | 1.92 × 104 | 1.37 × 105 | 6.69 × 103 | |

| F14 | 1.13 × 105 | 7.46 × 105 | 3.16 × 105 | 3.71 × 105 | 8.44 × 104 | 4.93 × 104 | 4.21 × 104 | 2.47 × 103 | 1.48 × 103 | |

| F15 | 3.88 × 104 | 6.48 × 103 | 1.19 × 104 | 1.25 × 105 | 5.58 × 103 | 4.56 × 104 | 1.35 × 104 | 3.05 × 104 | 1.72 × 103 | |

| F16 | 2.98 × 103 | 3.03 × 103 | 3.03 × 103 | 3.34 × 103 | 2.65 × 103 | 2.65 × 103 | 2.36 × 103 | 2.82 × 103 | 2.38 × 103 | |

| F17 | 2.19 × 103 | 2.34 × 103 | 2.45 × 103 | 2.57 × 103 | 2.15 × 103 | 2.17 × 103 | 1.91 × 103 | 2.17 × 103 | 1.89 × 103 | |

| F18 | 1.22 × 106 | 2.60 × 106 | 3.33 × 106 | 3.62 × 106 | 7.95 × 105 | 1.21 × 106 | 5.24 × 105 | 8.42 × 104 | 1.30 × 104 | |

| F19 | 2.03 × 106 | 8.73 × 103 | 7.55 × 103 | 1.70 × 106 | 8.19 × 103 | 5.13 × 105 | 1.37 × 104 | 2.50 × 104 | 2.06 × 103 | |

| F20 | 2.55 × 103 | 2.61 × 103 | 2.71 × 103 | 2.68 × 103 | 2.47 × 103 | 2.50 × 103 | 2.26 × 103 | 2.53 × 103 | 2.28 × 103 | |

| F21 | 2.43 × 103 | 2.45 × 103 | 2.51 × 103 | 2.55 × 103 | 2.40 × 103 | 2.42 × 103 | 2.36 × 103 | 2.44 × 103 | 2.36 × 103 | |

| F22 | 3.61 × 103 | 3.98 × 103 | 4.16 × 103 | 5.54 × 103 | 2.34 × 103 | 4.26 × 103 | 2.43 × 103 | 6.96 × 103 | 2.31 × 103 | |

| F23 | 2.81 × 103 | 3.11 × 103 | 2.89 × 103 | 3.00 × 103 | 2.79 × 103 | 2.79 × 103 | 2.73 × 103 | 2.79 × 103 | 2.72 × 103 | |

| F24 | 2.97 × 103 | 3.35 × 103 | 3.09 × 103 | 3.19 × 103 | 2.96 × 103 | 2.95 × 103 | 2.90 × 103 | 2.96 × 103 | 2.88 × 103 | |

| F25 | 2.95 × 103 | 2.96 × 103 | 2.91 × 103 | 2.98 × 103 | 2.97 × 103 | 2.91 × 103 | 2.91 × 103 | 2.92 × 103 | 2.89 × 103 | |

| F26 | 4.70 × 103 | 4.00 × 103 | 5.60 × 103 | 7.00 × 103 | 5.21 × 103 | 4.60 × 103 | 3.95 × 103 | 5.26 × 103 | 4.16 × 103 | |

| F27 | 3.30 × 103 | 3.27 × 103 | 3.49 × 103 | 3.31 × 103 | 3.27 × 103 | 3.25 × 103 | 3.22 × 103 | 3.24 × 103 | 3.23 × 103 | |

| F28 | 3.32 × 103 | 3.38 × 103 | 4.64 × 103 | 3.51 × 103 | 3.35 × 103 | 3.26 × 103 | 3.25 × 103 | 3.43 × 103 | 3.22 × 103 | |

| F29 | 4.31 × 103 | 4.04 × 103 | 4.34 × 103 | 4.40 × 103 | 3.91 × 103 | 3.96 × 103 | 3.65 × 103 | 4.03 × 103 | 3.65 × 103 | |

| F30 | 7.84 × 106 | 1.86 × 104 | 3.70 × 105 | 9.12 × 106 | 1.05 × 105 | 3.77 × 106 | 5.12 × 104 | 3.09 × 105 | 1.60 × 104 | |

| std | F1 | 2.07 × 107 | 5.34 × 105 | 1.05 × 106 | 1.77 × 108 | 2.00 × 107 | 3.95 × 104 | 3.14 × 104 | 5.77 × 107 | 2.17 × 103 |

| F3 | 8.40 × 103 | 2.17 × 104 | 4.84 × 104 | 4.24 × 104 | 7.81 × 103 | 8.49 × 103 | 7.00 × 103 | 9.50 × 103 | 1.77 × 103 | |

| F4 | 2.91 × 101 | 2.69 × 102 | 2.50 × 101 | 1.64 × 102 | 3.32 × 101 | 2.64 × 101 | 2.44 × 101 | 3.69 × 101 | 1.94 × 101 | |

| F5 | 4.48 × 101 | 3.10 × 101 | 5.17 × 101 | 6.12 × 101 | 3.54 × 101 | 3.78 × 101 | 2.08 × 101 | 1.71 × 101 | 1.81 × 101 | |

| F6 | 9.03 × 100 | 9.60 × 100 | 1.02 × 101 | 1.34 × 101 | 4.47 × 100 | 1.01 × 101 | 1.72 × 100 | 4.91 × 100 | 4.83 × 10−3 | |

| F7 | 5.80 × 101 | 4.56 × 101 | 1.01 × 102 | 6.42 × 101 | 6.38 × 101 | 3.41 × 101 | 2.96 × 101 | 3.55 × 101 | 2.10 × 101 | |

| F8 | 2.38 × 101 | 2.29 × 101 | 3.80 × 101 | 5.82 × 101 | 2.08 × 101 | 2.73 × 101 | 2.31 × 101 | 2.90 × 101 | 2.53 × 101 | |

| F9 | 8.78 × 102 | 1.06 × 103 | 1.07 × 103 | 2.31 × 103 | 7.36 × 102 | 2.29 × 103 | 3.59 × 102 | 7.94 × 102 | 1.56 × 100 | |

| F10 | 6.15 × 102 | 5.67 × 102 | 8.64 × 102 | 1.30 × 103 | 5.51 × 102 | 7.01 × 102 | 7.77 × 102 | 6.82 × 102 | 7.17 × 102 | |

| F11 | 1.58 × 102 | 1.50 × 103 | 1.21 × 102 | 1.17 × 103 | 6.40 × 101 | 5.29 × 101 | 4.22 × 101 | 5.06 × 101 | 3.40 × 101 | |

| F12 | 2.20 × 107 | 2.18 × 108 | 2.07 × 106 | 9.67 × 107 | 2.72 × 106 | 1.36 × 107 | 7.84 × 105 | 1.48 × 107 | 2.64 × 105 | |

| F13 | 4.50 × 104 | 1.37 × 108 | 4.22 × 104 | 1.50 × 107 | 1.29 × 104 | 1.02 × 105 | 1.87 × 104 | 1.20 × 105 | 3.44 × 103 | |

| F14 | 1.04 × 105 | 7.35 × 105 | 3.62 × 105 | 7.48 × 105 | 8.33 × 104 | 4.89 × 104 | 3.97 × 104 | 2.28 × 103 | 2.61 × 101 | |

| F15 | 1.94 × 104 | 6.88 × 103 | 1.33 × 104 | 3.06 × 105 | 5.73 × 103 | 3.16 × 104 | 1.34 × 104 | 1.39 × 104 | 1.06 × 102 | |

| F16 | 3.12 × 102 | 2.91 × 102 | 3.69 × 102 | 4.82 × 102 | 3.03 × 102 | 2.97 × 102 | 3.31 × 102 | 4.06 × 102 | 2.38 × 102 | |

| F17 | 2.21 × 102 | 2.68 × 102 | 2.60 × 102 | 2.52 × 102 | 2.01 × 102 | 1.96 × 102 | 1.34 × 102 | 1.52 × 102 | 1.06 × 102 | |

| F18 | 1.21 × 106 | 6.28 × 106 | 4.49 × 106 | 5.15 × 106 | 9.82 × 105 | 9.49 × 105 | 4.85 × 105 | 4.65 × 104 | 8.63 × 103 | |

| F19 | 1.35 × 106 | 8.91 × 103 | 9.82 × 103 | 2.45 × 106 | 6.99 × 103 | 5.14 × 105 | 1.49 × 104 | 1.77 × 104 | 2.65 × 102 | |

| F20 | 1.48 × 102 | 1.79 × 102 | 2.18 × 102 | 2.54 × 102 | 1.87 × 102 | 2.01 × 102 | 1.35 × 102 | 1.61 × 102 | 1.29 × 102 | |

| F21 | 3.39 × 101 | 3.93 × 101 | 4.89 × 101 | 5.20 × 101 | 2.07 × 101 | 2.35 × 101 | 1.72 × 101 | 3.03 × 101 | 2.04 × 101 | |

| F22 | 1.96 × 103 | 2.11 × 103 | 2.34 × 103 | 2.51 × 103 | 1.57 × 101 | 2.12 × 103 | 6.82 × 102 | 2.14 × 103 | 2.38 × 101 | |

| F23 | 5.03 × 101 | 1.53 × 102 | 7.45 × 101 | 8.72 × 101 | 4.27 × 101 | 4.00 × 101 | 2.38 × 101 | 2.86 × 101 | 1.70 × 101 | |

| F24 | 4.61 × 101 | 1.29 × 102 | 6.17 × 101 | 1.36 × 102 | 2.78 × 101 | 4.65 × 101 | 2.24 × 101 | 3.27 × 101 | 2.89 × 101 | |

| F25 | 2.95 × 101 | 3.31 × 101 | 2.20 × 101 | 4.24 × 101 | 2.97 × 101 | 2.31 × 101 | 1.83 × 101 | 1.47 × 101 | 1.37 × 100 | |

| F26 | 1.18 × 103 | 1.82 × 103 | 1.61 × 103 | 1.10 × 103 | 1.21 × 103 | 9.19 × 102 | 7.78 × 102 | 5.29 × 102 | 3.43 × 102 | |

| F27 | 4.40 × 101 | 2.07 × 102 | 1.38 × 102 | 5.94 × 101 | 2.39 × 101 | 2.40 × 101 | 1.14 × 101 | 1.85 × 101 | 1.41 × 101 | |

| F28 | 3.33 × 101 | 1.31 × 102 | 1.48 × 103 | 2.92 × 102 | 3.25 × 101 | 3.35 × 101 | 3.14 × 101 | 5.43 × 102 | 1.81 × 101 | |

| F29 | 1.88 × 102 | 3.35 × 102 | 3.20 × 102 | 2.93 × 102 | 2.47 × 102 | 2.12 × 102 | 2.03 × 102 | 2.52 × 102 | 1.10 × 102 | |

| F30 | 5.66 × 106 | 5.16 × 104 | 1.08 × 106 | 1.44 × 107 | 1.18 × 105 | 2.53 × 106 | 1.25 × 105 | 3.50 × 105 | 5.52 × 103 |

| VPPSO | IAGWO | IWOA | DBO | ARO | AOO | SBOA | ALA | IALA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | F1 | 6.95 × 108 | 1.80 × 107 | 1.71 × 108 | 7.48 × 109 | 2.81 × 109 | 1.68 × 106 | 1.80 × 107 | 2.05 × 109 | 4.44 × 103 |

| F3 | 1.44 × 105 | 1.72 × 105 | 2.85 × 105 | 2.83 × 105 | 1.65 × 105 | 1.34 × 105 | 1.04 × 105 | 1.13 × 105 | 3.63 × 104 | |

| F4 | 8.25 × 102 | 7.34 × 102 | 7.07 × 102 | 1.59 × 103 | 1.05 × 103 | 6.34 × 102 | 6.31 × 102 | 8.75 × 102 | 5.95 × 102 | |

| F5 | 7.95 × 102 | 7.80 × 102 | 8.89 × 102 | 9.60 × 102 | 7.79 × 102 | 7.50 × 102 | 7.22 × 102 | 8.44 × 102 | 6.28 × 102 | |

| F6 | 6.52 × 102 | 6.35 × 102 | 6.69 × 102 | 6.66 × 102 | 6.30 × 102 | 6.44 × 102 | 6.16 × 102 | 6.38 × 102 | 6.00 × 102 | |

| F7 | 1.25 × 103 | 1.19 × 103 | 1.53 × 103 | 1.39 × 103 | 1.36 × 103 | 1.05 × 103 | 1.13 × 103 | 1.30 × 103 | 8.71 × 102 | |

| F8 | 1.10 × 103 | 1.09 × 103 | 1.16 × 103 | 1.30 × 103 | 1.10 × 103 | 1.07 × 103 | 1.01 × 103 | 1.13 × 103 | 9.39 × 102 | |

| F9 | 1.04 × 104 | 1.57 × 104 | 1.56 × 104 | 2.96 × 104 | 1.04 × 104 | 1.23 × 104 | 5.54 × 103 | 1.06 × 104 | 9.80 × 102 | |

| F10 | 8.34 × 103 | 7.14 × 103 | 8.78 × 103 | 1.17 × 104 | 8.03 × 103 | 8.02 × 103 | 6.97 × 103 | 1.20 × 104 | 9.84 × 103 | |

| F11 | 2.40 × 103 | 4.67 × 103 | 1.84 × 103 | 5.09 × 103 | 2.25 × 103 | 1.57 × 103 | 1.48 × 103 | 2.10 × 103 | 1.29 × 103 | |

| F12 | 1.91 × 108 | 1.53 × 108 | 4.35 × 107 | 8.30 × 108 | 8.64 × 107 | 7.78 × 107 | 1.45 × 107 | 1.66 × 108 | 3.06 × 106 | |

| F13 | 9.99 × 104 | 2.77 × 108 | 9.71 × 104 | 1.47 × 108 | 2.35 × 105 | 1.34 × 105 | 1.13 × 104 | 2.06 × 106 | 2.26 × 104 | |

| F14 | 6.17 × 105 | 1.65 × 107 | 1.26 × 106 | 4.44 × 106 | 9.00 × 105 | 5.12 × 105 | 2.39 × 105 | 5.73 × 104 | 9.23 × 103 | |

| F15 | 3.39 × 104 | 3.90 × 107 | 3.12 × 104 | 8.34 × 106 | 1.08 × 104 | 5.24 × 104 | 1.10 × 104 | 1.01 × 105 | 3.61 × 103 | |

| F16 | 3.54 × 103 | 3.87 × 103 | 4.03 × 103 | 4.79 × 103 | 3.41 × 103 | 3.42 × 103 | 3.13 × 103 | 4.22 × 103 | 3.33 × 103 | |

| F17 | 3.39 × 103 | 3.49 × 103 | 3.60 × 103 | 4.18 × 103 | 3.08 × 103 | 3.11 × 103 | 2.71 × 103 | 3.44 × 103 | 2.85 × 103 | |

| F18 | 5.18 × 106 | 8.86 × 106 | 5.00 × 106 | 1.41 × 107 | 3.34 × 106 | 3.22 × 106 | 2.47 × 106 | 7.44 × 105 | 1.28 × 105 | |

| F19 | 1.58 × 106 | 1.53 × 104 | 4.17 × 104 | 8.17 × 106 | 1.69 × 104 | 1.20 × 106 | 1.90 × 104 | 1.80 × 105 | 8.12 × 103 | |

| F20 | 3.19 × 103 | 3.25 × 103 | 3.73 × 103 | 3.73 × 103 | 3.16 × 103 | 3.08 × 103 | 2.88 × 103 | 3.42 × 103 | 3.02 × 103 | |

| F21 | 2.58 × 103 | 2.61 × 103 | 2.74 × 103 | 2.87 × 103 | 2.55 × 103 | 2.54 × 103 | 2.47 × 103 | 2.63 × 103 | 2.43 × 103 | |

| F22 | 9.40 × 103 | 9.65 × 103 | 1.08 × 104 | 1.38 × 104 | 9.31 × 103 | 9.36 × 103 | 7.80 × 103 | 1.35 × 104 | 1.15 × 104 | |

| F23 | 3.13 × 103 | 3.78 × 103 | 3.33 × 103 | 3.56 × 103 | 3.13 × 103 | 3.05 × 103 | 2.94 × 103 | 3.11 × 103 | 2.87 × 103 | |

| F24 | 3.25 × 103 | 4.01 × 103 | 3.42 × 103 | 3.71 × 103 | 3.27 × 103 | 3.23 × 103 | 3.10 × 103 | 3.24 × 103 | 3.03 × 103 | |

| F25 | 3.33 × 103 | 3.31 × 103 | 3.18 × 103 | 3.65 × 103 | 3.53 × 103 | 3.11 × 103 | 3.16 × 103 | 3.38 × 103 | 3.08 × 103 | |

| F26 | 8.19 × 103 | 7.98 × 103 | 7.58 × 103 | 1.06 × 104 | 9.19 × 103 | 5.77 × 103 | 6.40 × 103 | 7.57 × 103 | 5.11 × 103 | |

| F27 | 3.75 × 103 | 3.56 × 103 | 4.14 × 103 | 3.89 × 103 | 3.78 × 103 | 3.64 × 103 | 3.39 × 103 | 3.54 × 103 | 3.48 × 103 | |

| F28 | 3.86 × 103 | 3.57 × 103 | 9.15 × 103 | 6.14 × 103 | 4.24 × 103 | 3.39 × 103 | 3.47 × 103 | 4.97 × 103 | 3.35 × 103 | |

| F29 | 5.56 × 103 | 5.35 × 103 | 5.40 × 103 | 6.65 × 103 | 4.88 × 103 | 4.96 × 103 | 4.12 × 103 | 5.21 × 103 | 4.29 × 103 | |

| F30 | 1.21 × 108 | 4.95 × 106 | 3.27 × 106 | 5.12 × 107 | 1.05 × 107 | 5.20 × 107 | 1.08 × 106 | 2.70 × 107 | 3.96 × 106 | |

| std | F1 | 6.88 × 108 | 4.57 × 106 | 8.02 × 107 | 1.13 × 1010 | 1.43 × 109 | 7.27 × 105 | 1.57 × 107 | 6.54 × 108 | 4.61 × 103 |

| F3 | 1.66 × 104 | 4.31 × 104 | 6.49 × 104 | 8.86 × 104 | 1.68 × 104 | 2.88 × 104 | 1.62 × 104 | 2.08 × 104 | 6.92 × 103 | |

| F4 | 9.55 × 101 | 2.05 × 102 | 6.73 × 101 | 1.49 × 103 | 2.25 × 102 | 3.76 × 101 | 5.62 × 101 | 8.07 × 101 | 3.39 × 101 | |

| F5 | 5.56 × 101 | 2.95 × 101 | 3.86 × 101 | 1.07 × 102 | 3.91 × 101 | 6.34 × 101 | 3.75 × 101 | 4.72 × 101 | 3.21 × 101 | |

| F6 | 6.57 × 100 | 5.92 × 100 | 3.04 × 100 | 1.35 × 101 | 7.55 × 100 | 9.88 × 100 | 6.12 × 100 | 8.21 × 100 | 1.22 × 10−1 | |

| F7 | 1.42 × 102 | 6.70 × 101 | 1.41 × 102 | 1.43 × 102 | 1.26 × 102 | 7.05 × 101 | 6.81 × 101 | 8.50 × 101 | 3.91 × 101 | |

| F8 | 4.98 × 101 | 3.85 × 101 | 6.37 × 101 | 9.88 × 101 | 4.18 × 101 | 4.75 × 101 | 3.81 × 101 | 4.74 × 101 | 4.22 × 101 | |

| F9 | 1.98 × 103 | 2.23 × 103 | 2.54 × 103 | 8.06 × 103 | 1.77 × 103 | 4.15 × 103 | 2.00 × 103 | 3.69 × 103 | 2.04 × 102 | |

| F10 | 1.20 × 103 | 9.04 × 102 | 1.05 × 103 | 2.52 × 103 | 7.46 × 102 | 9.51 × 102 | 8.42 × 102 | 1.21 × 103 | 8.96 × 102 | |

| F11 | 3.84 × 102 | 3.21 × 103 | 1.99 × 102 | 3.44 × 103 | 5.45 × 102 | 1.17 × 102 | 1.13 × 102 | 2.56 × 102 | 3.47 × 101 | |

| F12 | 1.66 × 108 | 7.06 × 108 | 2.39 × 107 | 5.35 × 108 | 3.79 × 107 | 3.53 × 107 | 1.09 × 107 | 6.27 × 107 | 1.64 × 106 | |

| F13 | 6.62 × 104 | 1.52 × 109 | 1.15 × 105 | 1.58 × 108 | 2.04 × 105 | 7.87 × 104 | 9.40 × 103 | 1.60 × 106 | 8.65 × 103 | |

| F14 | 3.69 × 105 | 2.61 × 107 | 1.05 × 106 | 5.29 × 106 | 7.28 × 105 | 3.16 × 105 | 1.68 × 105 | 8.67 × 104 | 1.14 × 104 | |

| F15 | 1.94 × 104 | 1.45 × 108 | 1.61 × 104 | 2.13 × 107 | 6.43 × 103 | 2.64 × 104 | 9.31 × 103 | 6.77 × 104 | 1.29 × 103 | |

| F16 | 3.51 × 102 | 5.98 × 102 | 4.41 × 102 | 6.05 × 102 | 4.51 × 102 | 4.05 × 102 | 4.30 × 102 | 4.70 × 102 | 3.14 × 102 | |

| F17 | 3.04 × 102 | 3.15 × 102 | 3.45 × 102 | 4.37 × 102 | 2.79 × 102 | 3.01 × 102 | 3.55 × 102 | 3.54 × 102 | 2.41 × 102 | |

| F18 | 3.81 × 106 | 1.99 × 107 | 3.43 × 106 | 1.46 × 107 | 2.49 × 106 | 2.19 × 106 | 2.16 × 106 | 6.57 × 105 | 1.31 × 105 | |

| F19 | 1.68 × 106 | 9.06 × 103 | 6.24 × 104 | 1.17 × 107 | 1.10 × 104 | 1.03 × 106 | 1.39 × 104 | 2.08 × 105 | 5.51 × 103 | |

| F20 | 3.34 × 102 | 2.95 × 102 | 3.37 × 102 | 4.06 × 102 | 3.74 × 102 | 2.93 × 102 | 2.12 × 102 | 3.77 × 102 | 2.48 × 102 | |

| F21 | 5.43 × 101 | 4.43 × 101 | 8.74 × 101 | 8.05 × 101 | 4.96 × 101 | 5.09 × 101 | 3.76 × 101 | 5.24 × 101 | 4.45 × 101 | |

| F22 | 1.63 × 103 | 1.96 × 103 | 1.39 × 103 | 2.04 × 103 | 1.97 × 103 | 1.04 × 103 | 2.81 × 103 | 2.22 × 103 | 1.06 × 103 | |

| F23 | 8.40 × 101 | 3.38 × 102 | 1.39 × 102 | 1.31 × 102 | 6.70 × 101 | 6.89 × 101 | 4.44 × 101 | 3.99 × 101 | 3.85 × 101 | |

| F24 | 6.47 × 101 | 2.17 × 102 | 1.58 × 102 | 1.92 × 102 | 5.31 × 101 | 8.34 × 101 | 4.95 × 101 | 4.87 × 101 | 4.13 × 101 | |

| F25 | 1.00 × 102 | 1.62 × 102 | 3.66 × 101 | 1.15 × 103 | 1.70 × 102 | 2.34 × 101 | 5.63 × 101 | 1.10 × 102 | 1.90 × 101 | |

| F26 | 2.02 × 103 | 2.24 × 103 | 3.23 × 103 | 1.68 × 103 | 1.88 × 103 | 2.04 × 103 | 1.33 × 103 | 6.60 × 102 | 4.07 × 102 | |

| F27 | 1.35 × 102 | 6.30 × 102 | 3.97 × 102 | 2.31 × 102 | 1.08 × 102 | 1.11 × 102 | 5.95 × 101 | 1.24 × 102 | 7.98 × 101 | |

| F28 | 1.81 × 102 | 5.46 × 102 | 3.90 × 103 | 2.16 × 103 | 2.36 × 102 | 4.02 × 101 | 6.52 × 101 | 1.92 × 103 | 3.62 × 101 | |

| F29 | 4.27 × 102 | 2.29 × 103 | 6.32 × 102 | 1.05 × 103 | 3.66 × 102 | 3.45 × 102 | 3.70 × 102 | 3.82 × 102 | 2.92 × 102 | |

| F30 | 3.51 × 107 | 1.55 × 107 | 1.36 × 106 | 6.81 × 107 | 4.30 × 106 | 1.65 × 107 | 2.74 × 105 | 1.23 × 107 | 1.09 × 106 |

| VPPSO | IAGWO | IWOA | DBO | ARO | AOO | SBOA | ALA | IALA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | F1 | 1.86 × 1010 | 3.22 × 108 | 8.99 × 109 | 9.11 × 1010 | 5.17 × 1010 | 4.33 × 108 | 1.44 × 1010 | 3.25 × 1010 | 1.20 × 107 |

| F3 | 3.91 × 105 | 4.95 × 105 | 8.22 × 105 | 6.90 × 105 | 3.81 × 105 | 5.85 × 105 | 3.39 × 105 | 3.18 × 105 | 2.20 × 105 | |

| F4 | 2.93 × 103 | 3.88 × 103 | 1.97 × 103 | 1.52 × 104 | 6.31 × 103 | 1.01 × 103 | 1.68 × 103 | 3.68 × 103 | 8.36 × 102 | |

| F5 | 1.30 × 103 | 1.27 × 103 | 1.50 × 103 | 1.64 × 103 | 1.44 × 103 | 1.28 × 103 | 1.16 × 103 | 1.52 × 103 | 9.10 × 102 | |

| F6 | 6.62 × 102 | 6.48 × 102 | 6.72 × 102 | 6.78 × 102 | 6.56 × 102 | 6.63 × 102 | 6.41 × 102 | 6.70 × 102 | 6.03 × 102 | |

| F7 | 2.66 × 103 | 2.28 × 103 | 3.14 × 103 | 2.99 × 103 | 2.95 × 103 | 2.02 × 103 | 2.38 × 103 | 2.65 × 103 | 1.22 × 103 | |

| F8 | 1.67 × 103 | 1.63 × 103 | 1.94 × 103 | 2.16 × 103 | 1.76 × 103 | 1.52 × 103 | 1.50 × 103 | 1.83 × 103 | 1.20 × 103 | |

| F9 | 2.67 × 104 | 4.16 × 104 | 3.41 × 104 | 7.73 × 104 | 3.41 × 104 | 3.75 × 104 | 2.75 × 104 | 5.20 × 104 | 4.36 × 103 | |

| F10 | 1.79 × 104 | 1.67 × 104 | 1.93 × 104 | 2.92 × 104 | 2.02 × 104 | 1.80 × 104 | 1.72 × 104 | 2.81 × 104 | 2.40 × 104 | |

| F11 | 7.36 × 104 | 7.53 × 104 | 1.58 × 105 | 2.31 × 105 | 8.53 × 104 | 3.65 × 104 | 3.70 × 104 | 6.53 × 104 | 9.19 × 103 | |

| F12 | 1.37 × 109 | 4.76 × 109 | 8.58 × 108 | 7.80 × 109 | 3.92 × 109 | 5.90 × 108 | 2.99 × 108 | 3.06 × 109 | 3.62 × 107 | |

| F13 | 1.88 × 105 | 2.05 × 105 | 9.22 × 105 | 2.66 × 108 | 1.53 × 107 | 7.48 × 104 | 4.09 × 104 | 5.87 × 107 | 1.12 × 104 | |

| F14 | 6.03 × 106 | 8.43 × 106 | 4.20 × 106 | 1.94 × 107 | 6.20 × 106 | 3.99 × 106 | 3.79 × 106 | 3.26 × 106 | 5.35 × 105 | |

| F15 | 5.43 × 105 | 2.36 × 104 | 6.12 × 104 | 1.13 × 108 | 2.18 × 105 | 8.38 × 104 | 7.19 × 103 | 5.44 × 106 | 1.27 × 104 | |

| F16 | 7.53 × 103 | 7.25 × 103 | 7.03 × 103 | 9.82 × 103 | 6.83 × 103 | 6.50 × 103 | 5.73 × 103 | 8.74 × 103 | 6.72 × 103 | |

| F17 | 5.56 × 103 | 1.20 × 104 | 6.08 × 103 | 9.10 × 103 | 5.12 × 103 | 5.28 × 103 | 4.86 × 103 | 6.55 × 103 | 4.80 × 103 | |

| F18 | 5.44 × 106 | 1.49 × 107 | 7.63 × 106 | 2.78 × 107 | 5.38 × 106 | 4.86 × 106 | 4.57 × 106 | 4.80 × 106 | 6.80 × 105 | |

| F19 | 6.63 × 106 | 3.13 × 105 | 6.92 × 105 | 1.20 × 108 | 7.00 × 105 | 5.03 × 106 | 1.03 × 104 | 1.11 × 107 | 1.66 × 104 | |

| F20 | 5.57 × 103 | 5.29 × 103 | 6.00 × 103 | 7.39 × 103 | 5.29 × 103 | 5.28 × 103 | 4.67 × 103 | 6.62 × 103 | 5.72 × 103 | |

| F21 | 3.21 × 103 | 4.27 × 103 | 3.62 × 103 | 4.00 × 103 | 3.20 × 103 | 3.14 × 103 | 2.96 × 103 | 3.35 × 103 | 2.76 × 103 | |

| F22 | 2.12 × 104 | 1.97 × 104 | 2.26 × 104 | 2.92 × 104 | 2.24 × 104 | 2.05 × 104 | 2.05 × 104 | 3.06 × 104 | 2.65 × 104 | |

| F23 | 3.90 × 103 | 6.03 × 103 | 4.13 × 103 | 4.80 × 103 | 3.87 × 103 | 3.82 × 103 | 3.39 × 103 | 3.84 × 103 | 3.26 × 103 | |

| F24 | 4.73 × 103 | 6.82 × 103 | 5.01 × 103 | 6.14 × 103 | 4.90 × 103 | 4.51 × 103 | 4.06 × 103 | 4.47 × 103 | 3.77 × 103 | |

| F25 | 5.29 × 103 | 4.85 × 103 | 4.43 × 103 | 8.62 × 103 | 6.64 × 103 | 3.82 × 103 | 4.25 × 103 | 6.04 × 103 | 3.52 × 103 | |

| F26 | 2.16 × 104 | 2.00 × 104 | 2.41 × 104 | 2.79 × 104 | 2.53 × 104 | 1.62 × 104 | 1.89 × 104 | 1.75 × 104 | 9.97 × 103 | |

| F27 | 4.52 × 103 | 5.39 × 103 | 7.44 × 103 | 4.73 × 103 | 4.57 × 103 | 4.11 × 103 | 3.77 × 103 | 3.92 × 103 | 3.76 × 103 | |

| F28 | 6.32 × 103 | 6.12 × 103 | 2.15 × 104 | 1.93 × 104 | 9.33 × 103 | 3.93 × 103 | 4.91 × 103 | 1.03 × 104 | 3.72 × 103 | |

| F29 | 1.06 × 104 | 7.68 × 103 | 8.47 × 103 | 1.14 × 104 | 9.07 × 103 | 8.81 × 103 | 7.14 × 103 | 9.64 × 103 | 7.83 × 103 | |

| F30 | 3.65 × 108 | 3.37 × 108 | 1.22 × 107 | 2.75 × 108 | 5.73 × 107 | 8.70 × 107 | 1.04 × 106 | 6.31 × 107 | 5.24 × 105 | |

| std | F1 | 4.88 × 109 | 7.22 × 107 | 2.26 × 109 | 7.28 × 1010 | 1.11 × 1010 | 1.76 × 108 | 6.25 × 109 | 6.40 × 109 | 1.46 × 107 |

| F3 | 4.62 × 104 | 1.52 × 105 | 1.80 × 105 | 2.86 × 105 | 2.74 × 104 | 9.62 × 104 | 2.03 × 104 | 3.88 × 104 | 2.89 × 104 | |

| F4 | 5.18 × 102 | 6.13 × 103 | 3.11 × 102 | 1.38 × 104 | 1.48 × 103 | 7.81 × 101 | 4.26 × 102 | 6.72 × 102 | 4.05 × 101 | |

| F5 | 1.17 × 102 | 6.04 × 101 | 4.62 × 101 | 1.82 × 102 | 6.44 × 101 | 9.48 × 101 | 6.16 × 101 | 1.05 × 102 | 8.57 × 101 | |

| F6 | 5.10 × 100 | 5.41 × 100 | 3.14 × 100 | 1.28 × 101 | 7.11 × 100 | 6.93 × 100 | 5.79 × 100 | 7.68 × 100 | 1.00 × 100 | |

| F7 | 2.98 × 102 | 1.27 × 102 | 2.12 × 102 | 2.20 × 102 | 2.01 × 102 | 1.86 × 102 | 1.52 × 102 | 2.00 × 102 | 9.07 × 101 | |

| F8 | 6.32 × 101 | 8.12 × 101 | 7.76 × 101 | 1.98 × 102 | 9.70 × 101 | 1.09 × 102 | 8.99 × 101 | 9.50 × 101 | 8.67 × 101 | |

| F9 | 8.13 × 103 | 5.81 × 103 | 2.47 × 103 | 8.70 × 103 | 4.59 × 103 | 6.49 × 103 | 4.04 × 103 | 8.64 × 103 | 2.25 × 103 | |

| F10 | 2.65 × 103 | 2.86 × 103 | 1.49 × 103 | 3.61 × 103 | 1.62 × 103 | 1.77 × 103 | 1.48 × 103 | 1.48 × 103 | 2.43 × 103 | |

| F11 | 1.12 × 104 | 1.70 × 104 | 6.83 × 104 | 5.96 × 104 | 1.85 × 104 | 1.12 × 104 | 9.44 × 103 | 1.35 × 104 | 2.24 × 103 | |

| F12 | 6.14 × 108 | 1.04 × 1010 | 3.19 × 108 | 2.25 × 109 | 2.24 × 109 | 2.47 × 108 | 1.88 × 108 | 1.02 × 109 | 1.67 × 107 | |

| F13 | 6.95 × 105 | 5.26 × 105 | 5.28 × 105 | 1.84 × 108 | 1.05 × 107 | 2.26 × 104 | 1.80 × 104 | 2.77 × 107 | 4.05 × 103 | |

| F14 | 2.72 × 106 | 3.94 × 106 | 1.52 × 106 | 1.20 × 107 | 2.26 × 106 | 1.81 × 106 | 1.82 × 106 | 1.70 × 106 | 3.53 × 105 | |

| F15 | 2.70 × 106 | 4.11 × 104 | 2.13 × 104 | 1.66 × 108 | 1.38 × 105 | 9.09 × 104 | 3.65 × 103 | 4.93 × 106 | 5.01 × 103 | |

| F16 | 7.95 × 102 | 1.56 × 103 | 8.71 × 102 | 1.53 × 103 | 7.40 × 102 | 7.13 × 102 | 7.88 × 102 | 8.84 × 102 | 9.74 × 102 | |

| F17 | 5.83 × 102 | 3.30 × 104 | 7.13 × 102 | 1.48 × 103 | 5.12 × 102 | 6.76 × 102 | 5.75 × 102 | 4.77 × 102 | 4.66 × 102 | |

| F18 | 2.75 × 106 | 2.93 × 107 | 4.38 × 106 | 1.80 × 107 | 2.58 × 106 | 3.69 × 106 | 1.98 × 106 | 2.96 × 106 | 3.02 × 105 | |

| F19 | 6.10 × 106 | 1.68 × 106 | 7.39 × 105 | 9.98 × 107 | 4.54 × 105 | 3.85 × 106 | 1.01 × 104 | 6.96 × 106 | 1.38 × 104 | |

| F20 | 5.74 × 102 | 7.45 × 102 | 5.57 × 102 | 7.26 × 102 | 4.63 × 102 | 6.33 × 102 | 4.13 × 102 | 5.56 × 102 | 6.03 × 102 | |

| F21 | 1.13 × 102 | 6.09 × 102 | 1.15 × 102 | 1.65 × 102 | 9.29 × 101 | 1.14 × 102 | 8.00 × 101 | 8.27 × 101 | 9.23 × 101 | |

| F22 | 2.17 × 103 | 2.21 × 103 | 1.40 × 103 | 5.27 × 103 | 1.84 × 103 | 1.69 × 103 | 1.53 × 103 | 1.39 × 103 | 2.13 × 103 | |

| F23 | 1.18 × 102 | 4.19 × 102 | 2.27 × 102 | 2.30 × 102 | 1.27 × 102 | 1.56 × 102 | 7.24 × 101 | 1.00 × 102 | 8.98 × 101 | |

| F24 | 2.34 × 102 | 9.20 × 102 | 3.14 × 102 | 3.98 × 102 | 2.56 × 102 | 1.51 × 102 | 1.20 × 102 | 1.04 × 102 | 1.01 × 102 | |

| F25 | 4.17 × 102 | 1.07 × 103 | 2.19 × 102 | 4.78 × 103 | 6.68 × 102 | 1.07 × 102 | 2.73 × 102 | 7.91 × 102 | 5.39 × 101 | |

| F26 | 2.73 × 103 | 5.88 × 103 | 2.29 × 103 | 3.36 × 103 | 2.36 × 103 | 4.19 × 103 | 3.15 × 103 | 1.09 × 103 | 8.85 × 102 | |

| F27 | 2.55 × 102 | 2.44 × 103 | 1.88 × 103 | 4.45 × 102 | 2.42 × 102 | 1.69 × 102 | 1.60 × 102 | 1.48 × 102 | 9.95 × 101 | |

| F28 | 7.99 × 102 | 2.67 × 103 | 7.58 × 103 | 5.91 × 103 | 9.77 × 102 | 1.49 × 102 | 3.94 × 102 | 4.41 × 103 | 8.93 × 101 | |

| F29 | 1.04 × 103 | 1.57 × 103 | 7.79 × 102 | 2.02 × 103 | 7.37 × 102 | 8.66 × 102 | 9.22 × 102 | 8.40 × 102 | 5.98 × 102 | |

| F30 | 1.82 × 108 | 9.43 × 108 | 6.08 × 106 | 1.71 × 108 | 4.68 × 107 | 4.01 × 107 | 9.22 × 105 | 2.30 × 107 | 2.08 × 105 |

| Function | VPPSO | IAGWO | IWOA | DBO | ARO | AOO | SBOA | ALA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 1.53 × 10−5 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 5.97 × 10−9 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F3 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F4 | 3.83 × 10−6 | 2.78 × 10−7 | 2.13 × 10−4 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 2.67 × 10−9 | 3.71 × 10−1 | 5.11 × 10−1 | 6.72 × 10−10 |

| F5 | 2.37 × 10−10 | 3.34 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.47 × 10−10 | 1.09 × 10−10 | 5.61 × 10−5 | 4.50 × 10−11 |

| F6 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F7 | 3.69 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.69 × 10−11 | 1.61 × 10−10 | 2.03 × 10−9 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F8 | 1.29 × 10−9 | 4.57 × 10−9 | 5.49 × 10−11 | 1.09 × 10−10 | 2.57 × 10−7 | 4.35 × 10−5 | 1.76 × 10−2 | 2.03 × 10−9 |

| F9 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F10 | 6.79 × 10−2 | 8.66 × 10−5 | 3.67 × 10−3 | 7.74 × 10−6 | 1.00 × 10−3 | 5.75 × 10−2 | 6.20 × 10−4 | 7.04 × 10−7 |

| F11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 5.00 × 10−9 | 1.46 × 10−10 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 1.33 × 10−10 | 1.55 × 10−9 | 4.71 × 10−4 | 4.98 × 10−11 |

| F12 | 3.69 × 10−11 | 1.96 × 10−10 | 5.49 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 8.15 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 4.69 × 10−8 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F13 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 1.17 × 10−4 | 1.20 × 10−8 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 7.30 × 10−4 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 7.98 × 10−2 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F14 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F15 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 1.36 × 10−7 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.82 × 10−9 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 1.78 × 10−10 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F16 | 3.20 × 10−9 | 1.69 × 10−9 | 1.20 × 10−8 | 1.61 × 10−10 | 8.56 × 10−4 | 7.30 × 10−4 | 6.84 × 10−1 | 1.64 × 10−5 |

| F17 | 7.04 × 10−7 | 6.72 × 10−10 | 6.70 × 10−11 | 1.09 × 10−10 | 8.20 × 10−7 | 2.03 × 10−7 | 6.41 × 10−1 | 4.18 × 10−9 |

| F18 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.34 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 1.09 × 10−10 |

| F19 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 2.87 × 10−10 | 1.46 × 10−10 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 6.70 × 10−11 | 3.34 × 10−11 | 2.23 × 10−9 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F20 | 4.69 × 10−8 | 2.67 × 10−9 | 4.20 × 10−10 | 7.77 × 10−9 | 1.58 × 10−4 | 1.64 × 10−5 | 5.49 × 10−1 | 3.01 × 10−7 |

| F21 | 6.12 × 10−10 | 1.21 × 10−10 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 1.25 × 10−7 | 4.62 × 10−10 | 6.95 × 10−1 | 8.15 × 10−11 |

| F22 | 1.17 × 10−9 | 9.76 × 10−10 | 9.76 × 10−10 | 4.08 × 10−11 | 7.77 × 10−9 | 5.57 × 10−10 | 7.69 × 10−8 | 8.15 × 10−11 |

| F23 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 6.70 × 10−11 | 2.03 × 10−9 | 2.71 × 10−1 | 3.34 × 10−11 |

| F24 | 5.00 × 10−9 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 5.57 × 10−10 | 6.52 × 10−9 | 6.55 × 10−4 | 8.89 × 10−10 |

| F25 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 6.12 × 10−10 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 1.02 × 10−5 | 1.43 × 10−5 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F26 | 3.39 × 10−2 | 5.83 × 10−3 | 2.68 × 10−4 | 5.07 × 10−10 | 2.68 × 10−4 | 5.97 × 10−5 | 8.19 × 10−1 | 6.12 × 10−10 |

| F27 | 1.46 × 10−10 | 1.11 × 10−6 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 5.46 × 10−9 | 4.20 × 10−10 | 1.64 × 10−5 | 3.27 × 10−2 | 1.54 × 10−1 |

| F28 | 4.98 × 10−11 | 3.20 × 10−9 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 1.03 × 10−6 | 8.15 × 10−5 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F29 | 3.69 × 10−11 | 2.00 × 10−5 | 7.39 × 10−11 | 3.69 × 10−11 | 1.87 × 10−5 | 6.53 × 10−8 | 5.30 × 10−1 | 5.09 × 10−8 |

| F30 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 5.09 × 10−8 | 3.01 × 10−7 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 2.49 × 10−6 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.04 × 10−1 | 9.92 × 10−11 |

| Function | VPPSO | IAGWO | IWOA | DBO | ARO | AOO | SBOA | ALA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F3 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F4 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 1.20 × 10−8 | 2.92 × 10−9 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 7.20 × 10−5 | 1.08 × 10−2 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F5 | 3.34 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 1.96 × 10−10 | 2.15 × 10−10 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F6 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F7 | 3.34 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 6.70 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F8 | 4.50 × 10−11 | 4.50 × 10−11 | 4.08 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.34 × 10−11 | 1.78 × 10−10 | 2.57 × 10−7 | 3.69 × 10−11 |

| F9 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F10 | 1.60 × 10−7 | 1.96 × 10−10 | 6.36 × 10−5 | 1.22 × 10−2 | 5.00 × 10−9 | 2.83 × 10−8 | 4.50 × 10−11 | 3.65 × 10−8 |

| F11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.47 × 10−10 | 9.76 × 10−10 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F12 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 8.15 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.20 × 10−9 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F13 | 6.72 × 10−10 | 3.55 × 10−1 | 3.82 × 10−9 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 4.50 × 10−11 | 4.98 × 10−11 | 5.97 × 10−5 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F14 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.69 × 10−11 | 3.69 × 10−11 | 1.73 × 10−6 |

| F15 | 3.69 × 10−11 | 6.55 × 10−4 | 3.69 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 1.07 × 10−7 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 2.39 × 10−4 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F16 | 5.55 × 10−2 | 6.77 × 10−5 | 5.53 × 10−8 | 8.99 × 10−11 | 8.30 × 10−1 | 3.48 × 10−1 | 1.56 × 10−2 | 1.07 × 10−9 |

| F17 | 7.09 × 10−8 | 1.10 × 10−8 | 3.16 × 10−10 | 4.50 × 10−11 | 3.67 × 10−3 | 4.71 × 10−4 | 1.15 × 10−1 | 2.60 × 10−8 |

| F18 | 4.08 × 10−11 | 3.69 × 10−11 | 3.69 × 10−11 | 3.69 × 10−11 | 3.34 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 6.07 × 10−11 | 5.97 × 10−9 |

| F19 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 9.03 × 10−4 | 1.47 × 10−7 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.56 × 10−4 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 6.55 × 10−4 | 6.12 × 10−10 |

| F20 | 4.21 × 10−2 | 3.18 × 10−3 | 1.20 × 10−8 | 9.26 × 10−9 | 3.64 × 10−2 | 5.40 × 10−1 | 2.15 × 10−2 | 2.13 × 10−5 |

| F21 | 1.21 × 10−10 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 1.41 × 10−9 | 1.69 × 10−9 | 5.61 × 10−5 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F22 | 3.96 × 10−8 | 1.86 × 10−6 | 3.39 × 10−2 | 8.29 × 10−6 | 2.78 × 10−7 | 6.52 × 10−9 | 9.92 × 10−11 | 1.56 × 10−8 |

| F23 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 1.09 × 10−10 | 1.73 × 10−6 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F24 | 6.07 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 4.50 × 10−11 | 1.49 × 10−6 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F25 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 2.03 × 10−7 | 2.15 × 10−10 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F26 | 1.31 × 10−8 | 2.60 × 10−5 | 2.46 × 10−1 | 1.96 × 10−10 | 3.69 × 10−11 | 2.71 × 10−2 | 1.17 × 10−5 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F27 | 3.16 × 10−10 | 2.42 × 10−2 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 5.57 × 10−10 | 4.08 × 10−11 | 4.11 × 10−7 | 1.04 × 10−4 | 3.27 × 10−2 |

| F28 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 9.00 × 10−1 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 1.17 × 10−5 | 5.57 × 10−10 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F29 | 7.39 × 10−11 | 1.50 × 10−2 | 2.92 × 10−9 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 1.47 × 10−7 | 7.12 × 10−9 | 1.05 × 10−1 | 4.20 × 10−10 |

| F30 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 7.04 × 10−7 | 2.24 × 10−2 | 7.39 × 10−11 | 4.98 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| Function | VPPSO | IAGWO | IWOA | DBO | ARO | AOO | SBOA | ALA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F3 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 9.92 × 10−11 |

| F4 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 4.08 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F5 | 4.50 × 10−11 | 3.34 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 4.08 × 10−11 | 1.96 × 10−10 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F6 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F7 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F8 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 5.49 × 10−11 | 4.98 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F9 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F10 | 2.67 × 10−9 | 1.69 × 10−9 | 2.67 × 10−9 | 8.84 × 10−7 | 9.83 × 10−8 | 1.96 × 10−10 | 8.99 × 10−11 | 1.85 × 10−8 |

| F11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F12 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F13 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 2.61 × 10−10 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F14 | 3.69 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.69 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 5.49 × 10−11 | 4.98 × 10−11 | 2.37 × 10−10 |

| F15 | 1.96 × 10−10 | 6.97 × 10−3 | 3.34 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.34 × 10−11 | 1.87 × 10−5 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F16 | 9.52 × 10−4 | 2.90 × 10−1 | 1.30 × 10−1 | 8.10 × 10−10 | 4.12 × 10−1 | 5.79 × 10−1 | 1.89 × 10−4 | 9.26 × 10−9 |

| F17 | 4.42 × 10−6 | 5.97 × 10−5 | 4.18 × 10−9 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 1.08 × 10−2 | 3.85 × 10−3 | 7.84 × 10−1 | 4.50 × 10−11 |

| F18 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.34 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.69 × 10−11 |

| F19 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 9.03 × 10−4 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 2.51 × 10−2 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F20 | 3.95 × 10−1 | 1.63 × 10−2 | 5.75 × 10−2 | 2.92 × 10−9 | 5.08 × 10−3 | 1.27 × 10−2 | 2.02 × 10−8 | 1.86 × 10−6 |

| F21 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 4.98 × 10−11 | 1.69 × 10−9 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F22 | 4.18 × 10−9 | 2.61 × 10−10 | 5.97 × 10−9 | 9.33 × 10−2 | 3.08 × 10−8 | 2.61 × 10−10 | 1.46 × 10−10 | 1.17 × 10−9 |

| F23 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.69 × 10−11 | 9.53 × 10−7 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F24 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 2.15 × 10−10 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F25 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F26 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 1.16 × 10−7 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 1.11 × 10−6 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F27 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.79 × 10−1 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 4.50 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 4.20 × 10−10 | 7.39 × 10−1 | 1.75 × 10−5 |

| F28 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.69 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 1.36 × 10−7 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| F29 | 4.98 × 10−11 | 9.05 × 10−2 | 1.11 × 10−3 | 4.20 × 10−10 | 1.07 × 10−7 | 2.28 × 10−5 | 6.91 × 10−4 | 9.76 × 10−10 |

| F30 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 1.45 × 10−1 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.02 × 10−11 | 3.37 × 10−4 | 3.02 × 10−11 |

| VPPSO | IAGWO | IWOA | DBO | ARO | AOO | SBOA | ALA | IALA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1 | Mean | 5378.47 | 5827.43 | 6064.00 | 5874.96 | 5563.04 | 5652.05 | 5384.72 | 5777.49 | 5271.45 |

| Std | 132.88 | 246.70 | 433.91 | 308.21 | 79.79 | 378.04 | 117.91 | 203.26 | 28.24 | |

| Scenario 2 | Mean | 5421.14 | 5675.11 | 6481.74 | 5950.07 | 5504.32 | 5474.52 | 5365.36 | 5631.72 | 5275.16 |

| Std | 104.08 | 275.87 | 358.87 | 327.36 | 82.75 | 157.77 | 116.03 | 175.47 | 25.82 | |

| Scenario 3 | Mean | 6086.08 | 6055.68 | 8126.74 | 7084.96 | 6217.21 | 6005.43 | 5757.36 | 7041.82 | 5559.58 |

| Std | 332.17 | 280.81 | 991.73 | 438.57 | 285.46 | 241.88 | 104.86 | 392.45 | 47.34 | |

| Scenario 4 | Mean | 7061.43 | 7077.09 | 8860.45 | 8248.59 | 7477.85 | 7117.82 | 6647.13 | 7623.86 | 6158.55 |

| Std | 873.86 | 992.45 | 846.77 | 749.44 | 403.67 | 907.32 | 510.43 | 663.52 | 383.61 | |

| Scenario 5 | Mean | 5413.44 | 5812.97 | 6101.83 | 5641.98 | 5450.93 | 5446.25 | 5353.26 | 5512.53 | 5301.05 |

| Std | 124.47 | 319.20 | 534.25 | 130.90 | 62.55 | 94.20 | 112.40 | 153.63 | 28.09 | |

| Scenario 6 | Mean | 5590.65 | 5807.43 | 7102.22 | 6489.68 | 5816.67 | 5522.77 | 5484.60 | 5841.87 | 5349.86 |

| Std | 163.36 | 341.63 | 582.16 | 540.91 | 229.03 | 89.78 | 61.59 | 328.27 | 32.00 | |

| Scenario 7 | Mean | 6623.59 | 6580.92 | 7820.10 | 7041.78 | 6563.94 | 6086.49 | 6008.29 | 6592.28 | 6123.95 |

| Std | 559.11 | 441.13 | 611.80 | 458.18 | 344.97 | 267.89 | 293.38 | 281.06 | 290.84 | |

| Scenario 8 | Mean | 6486.19 | 6940.26 | 7119.20 | 7101.76 | 7416.30 | 6433.31 | 5932.86 | 6267.92 | 6191.59 |

| Std | 509.55 | 610.11 | 604.55 | 1058.16 | 770.65 | 542.81 | 378.27 | 577.36 | 187.29 |

| VPPSO | IAGWO | IWOA | DBO | ARO | AOO | SBOA | ALA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1 | 3.76 × 10−02 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 4.52 × 10−02 | 1.83 × 10−04 |

| Scenario 2 | 3.61 × 10−03 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 3.61 × 10−03 | 3.76 × 10−02 | 7.69 × 10−04 |

| Scenario 3 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 3.30 × 10−04 | 1.83 × 10−04 |

| Scenario 4 | 3.61 × 10−03 | 4.59 × 10−03 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 2.46 × 10−04 | 5.80 × 10−03 | 2.57 × 10−02 | 3.30 × 10−04 |

| Scenario 5 | 9.11 × 10−03 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 5.83 × 10−04 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 2.83 × 10−03 | 4.73 × 10−01 | 1.83 × 10−04 |

| Scenario 6 | 2.83 × 10−03 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 1.83 × 10−04 |

| Scenario 7 | 3.12 × 10−02 | 1.73 × 10−02 | 1.83 × 10−04 | 1.01 × 10−03 | 5.80 × 10−03 | 6.78 × 10−01 | 3.07 × 10−01 | 4.59 × 10−03 |

| Scenario 8 | 3.07 × 10−01 | 5.80 × 10−03 | 7.69 × 10−04 | 4.52 × 10−02 | 1.71 × 10−03 | 3.85 × 10−01 | 5.39 × 10−02 | 7.34 × 10−01 |

| VPPSO | IAGWO | IWOA |  | |||

| mean | std | mean | std | mean | std | |

| 196.55 | 8.56 | 55,126.89 | 85,346.37 | 93,036.67 | 94,518.23 | |

| Ranking | 3 | Ranking | 7 | Ranking | 8 | |

| DBO | ARO | AOO | ||||

| mean | std | mean | std | mean | std | |

| 116,809.27 | 96,913.18 | 6293.90 | 33,412.36 | 6284.40 | 33,355.41 | |

| Ranking | 9 | Ranking | 5 | Ranking | 4 | |

| SBOA | ALA | IALA | ||||

| mean | std | mean | std | mean | std | |

| 190.14 | 2.88 | 24,641.74 | 63,391.69 | 188.32 | 1.38 | |

| Ranking | 2 | Ranking | 6 | Ranking | 1 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zheng, X.; Liu, R.; Huang, S.; Duan, Z. IALA: An Improved Artificial Lemming Algorithm for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Path Planning. Technologies 2026, 14, 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14020091

Zheng X, Liu R, Huang S, Duan Z. IALA: An Improved Artificial Lemming Algorithm for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Path Planning. Technologies. 2026; 14(2):91. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14020091

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Xiaojun, Rundong Liu, Shiming Huang, and Zhicong Duan. 2026. "IALA: An Improved Artificial Lemming Algorithm for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Path Planning" Technologies 14, no. 2: 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14020091

APA StyleZheng, X., Liu, R., Huang, S., & Duan, Z. (2026). IALA: An Improved Artificial Lemming Algorithm for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Path Planning. Technologies, 14(2), 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14020091