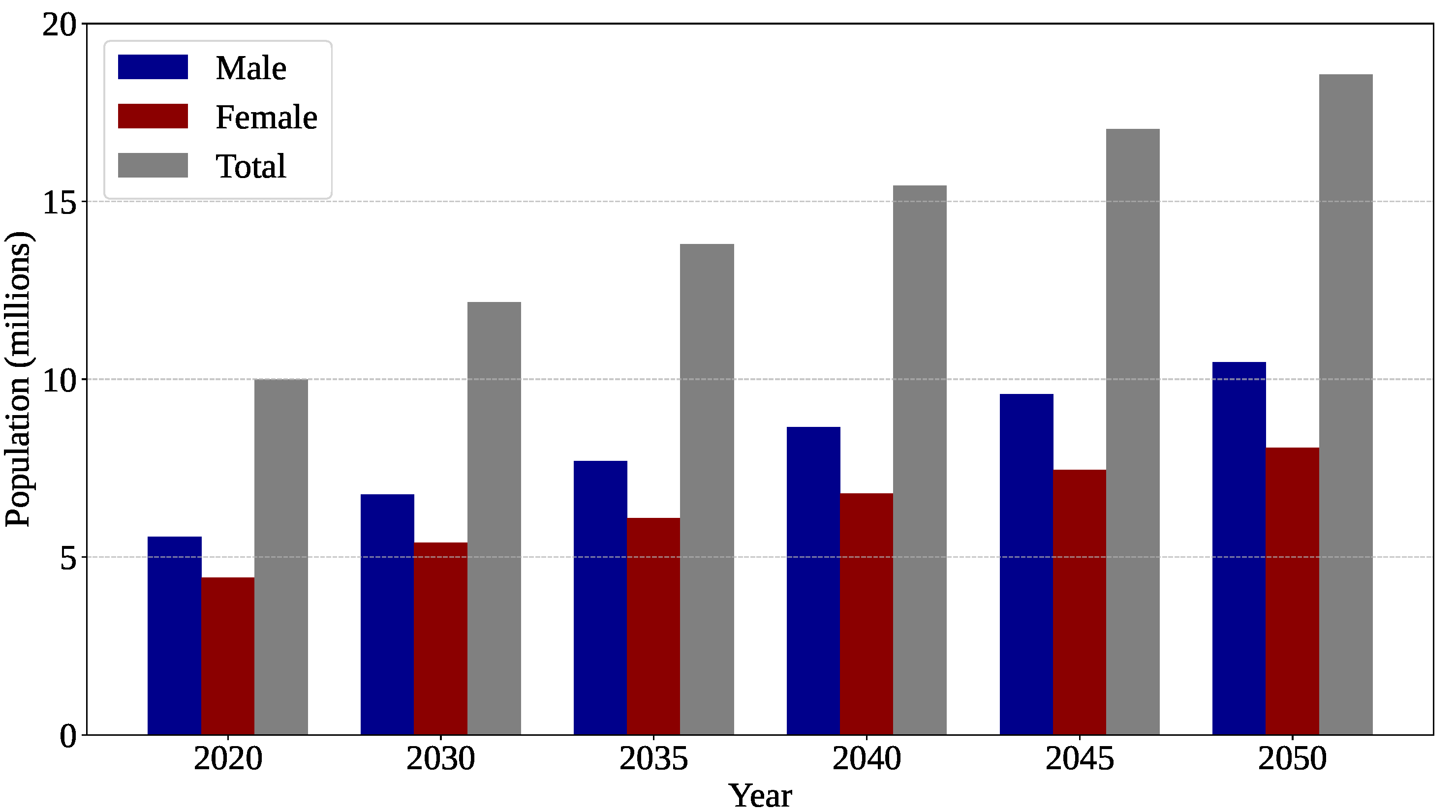

Figure 1.

Estimated global mortality rate attributable to brain tumors. Chart generated by the authors from data available at the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) website (

https://gco.iarc.who.int/tomorrow/en, accessed on 13 December 2025), the Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Tomorrow database [

12].

Figure 1.

Estimated global mortality rate attributable to brain tumors. Chart generated by the authors from data available at the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) website (

https://gco.iarc.who.int/tomorrow/en, accessed on 13 December 2025), the Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Tomorrow database [

12].

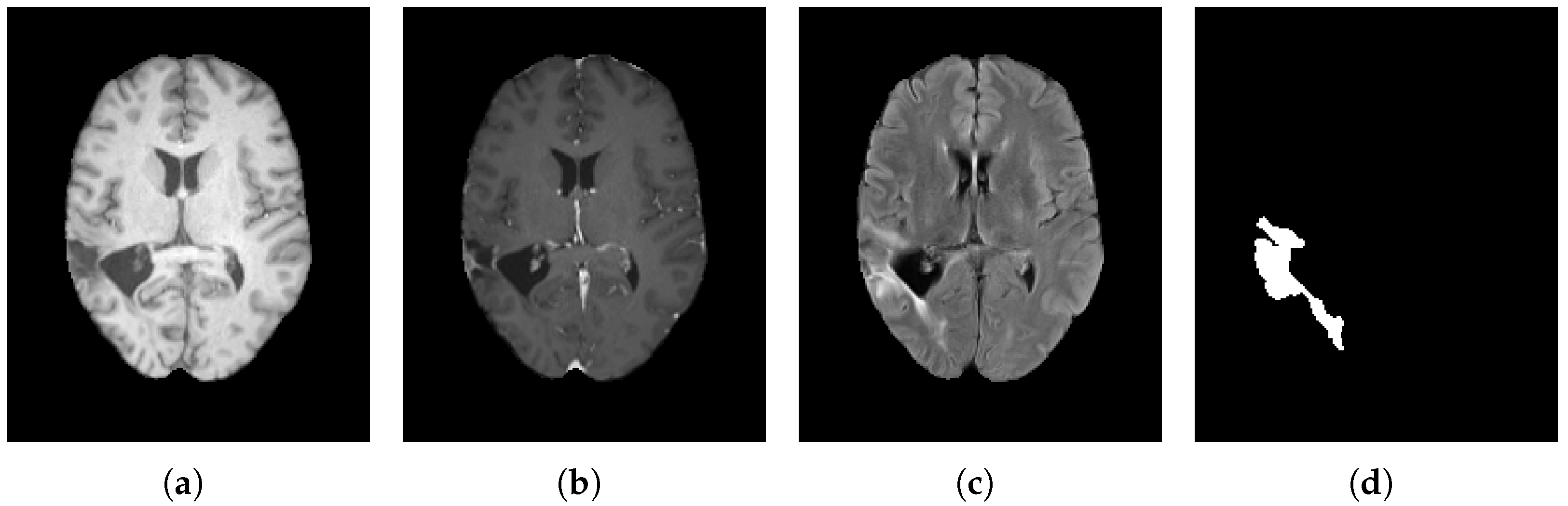

Figure 2.

Comparative axial slices from the BraTS 2023 dataset showing (a) native T1-weighted (T1), (b) contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1-C), and (c) T2-weighted (T2) MRI sequences, together with (d) the corresponding ground-truth tumor mask.

Figure 2.

Comparative axial slices from the BraTS 2023 dataset showing (a) native T1-weighted (T1), (b) contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1-C), and (c) T2-weighted (T2) MRI sequences, together with (d) the corresponding ground-truth tumor mask.

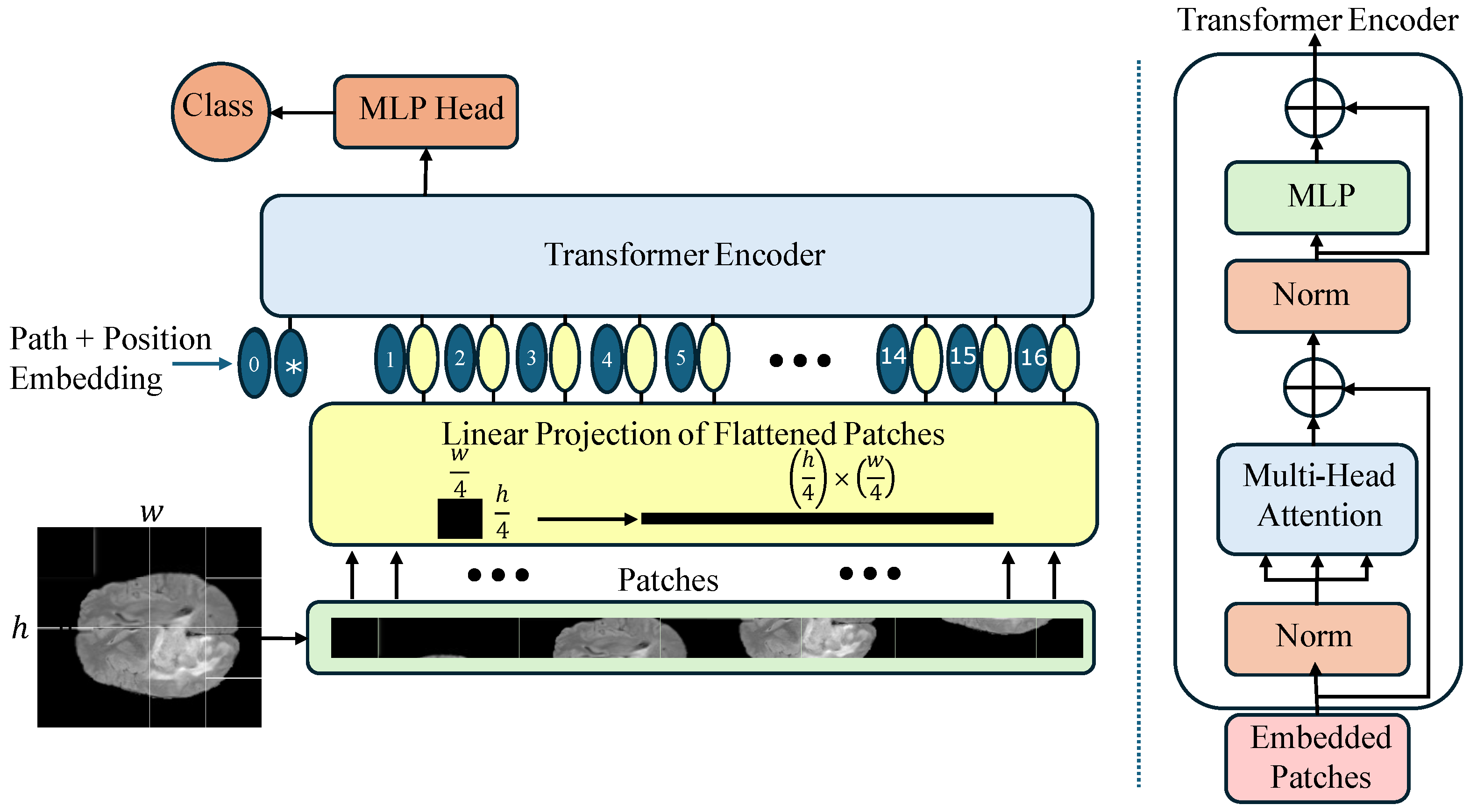

Figure 3.

Architectural overview of the Vision Transformer (ViT-Base) model, highlighting patch tokenization, positional encoding, stacked Transformer encoder layers, and the classification head.

Figure 3.

Architectural overview of the Vision Transformer (ViT-Base) model, highlighting patch tokenization, positional encoding, stacked Transformer encoder layers, and the classification head.

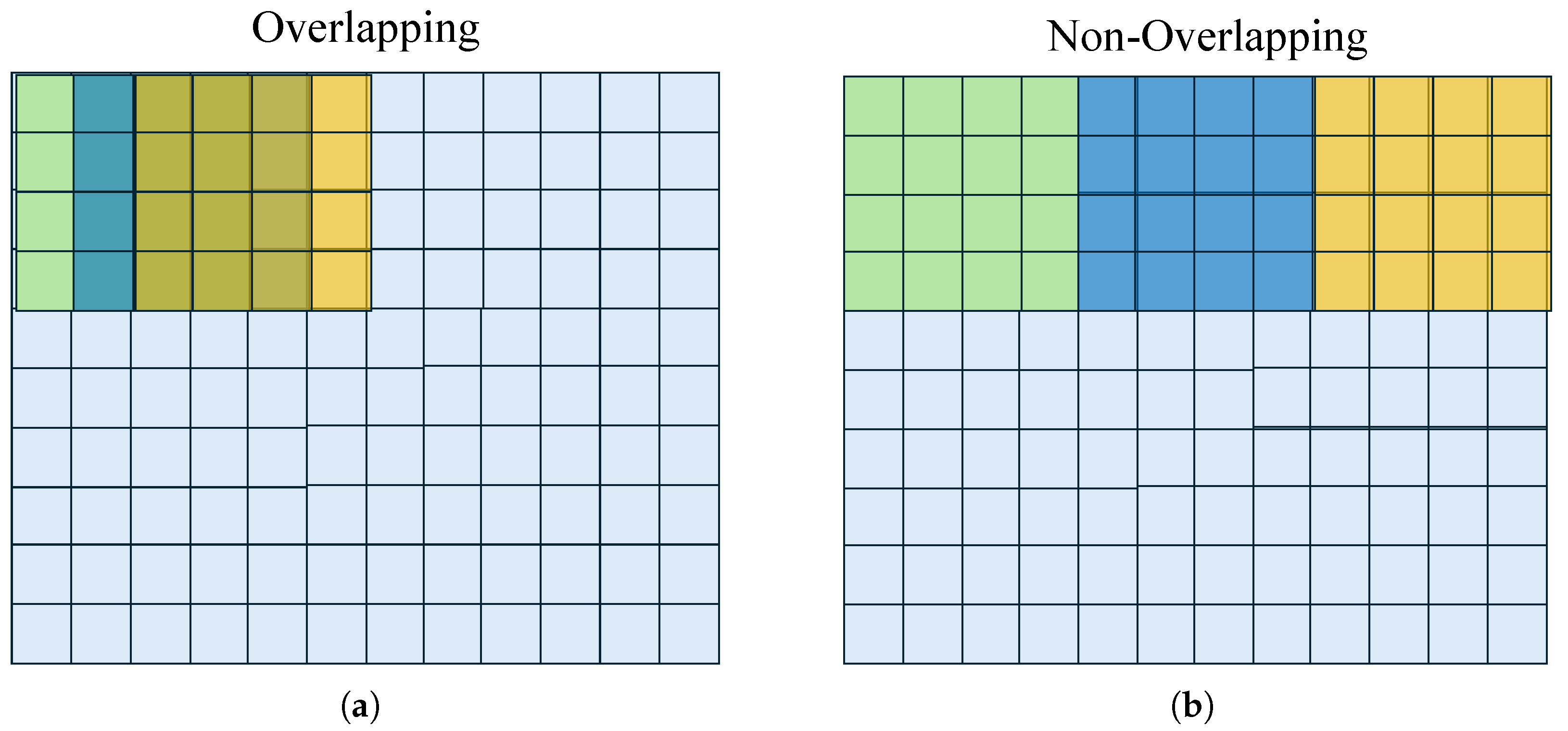

Figure 4.

Sampling configurations: (a) Partial overlapping (stride smaller than filter size), and (b) non-overlapping (stride equals filter size). Original image pixels in light-blue, sliding window in the -, -, and -iterations colored in green, blue, and yellow, respectively.

Figure 4.

Sampling configurations: (a) Partial overlapping (stride smaller than filter size), and (b) non-overlapping (stride equals filter size). Original image pixels in light-blue, sliding window in the -, -, and -iterations colored in green, blue, and yellow, respectively.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the Gaussian error linear unit (GELU) and the rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation functions. While ReLU enforces a hard zero-threshold, GELU introduces a smooth, probabilistic transition that better preserves negative values near the origin.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the Gaussian error linear unit (GELU) and the rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation functions. While ReLU enforces a hard zero-threshold, GELU introduces a smooth, probabilistic transition that better preserves negative values near the origin.

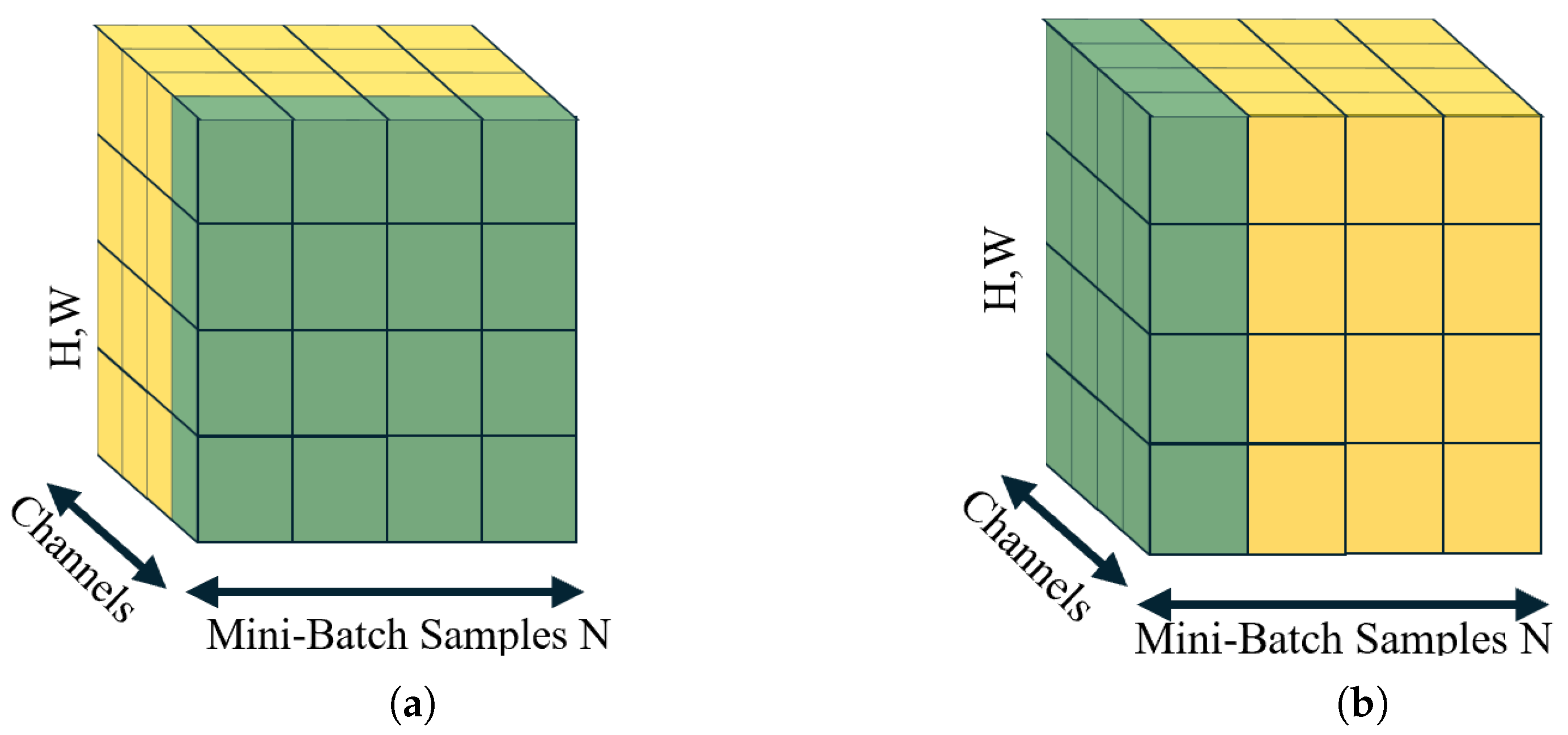

Figure 6.

Comparative overview of feature-wise normalization techniques: (a) Batch normalization (BN); statistics computed across the mini-batch for each feature channel; (b) layer normalization (LN); statistics computed across all features for each sample. The green color indicates the voxels to be analyzed, and the process continues with the adjacent yellow voxels.

Figure 6.

Comparative overview of feature-wise normalization techniques: (a) Batch normalization (BN); statistics computed across the mini-batch for each feature channel; (b) layer normalization (LN); statistics computed across all features for each sample. The green color indicates the voxels to be analyzed, and the process continues with the adjacent yellow voxels.

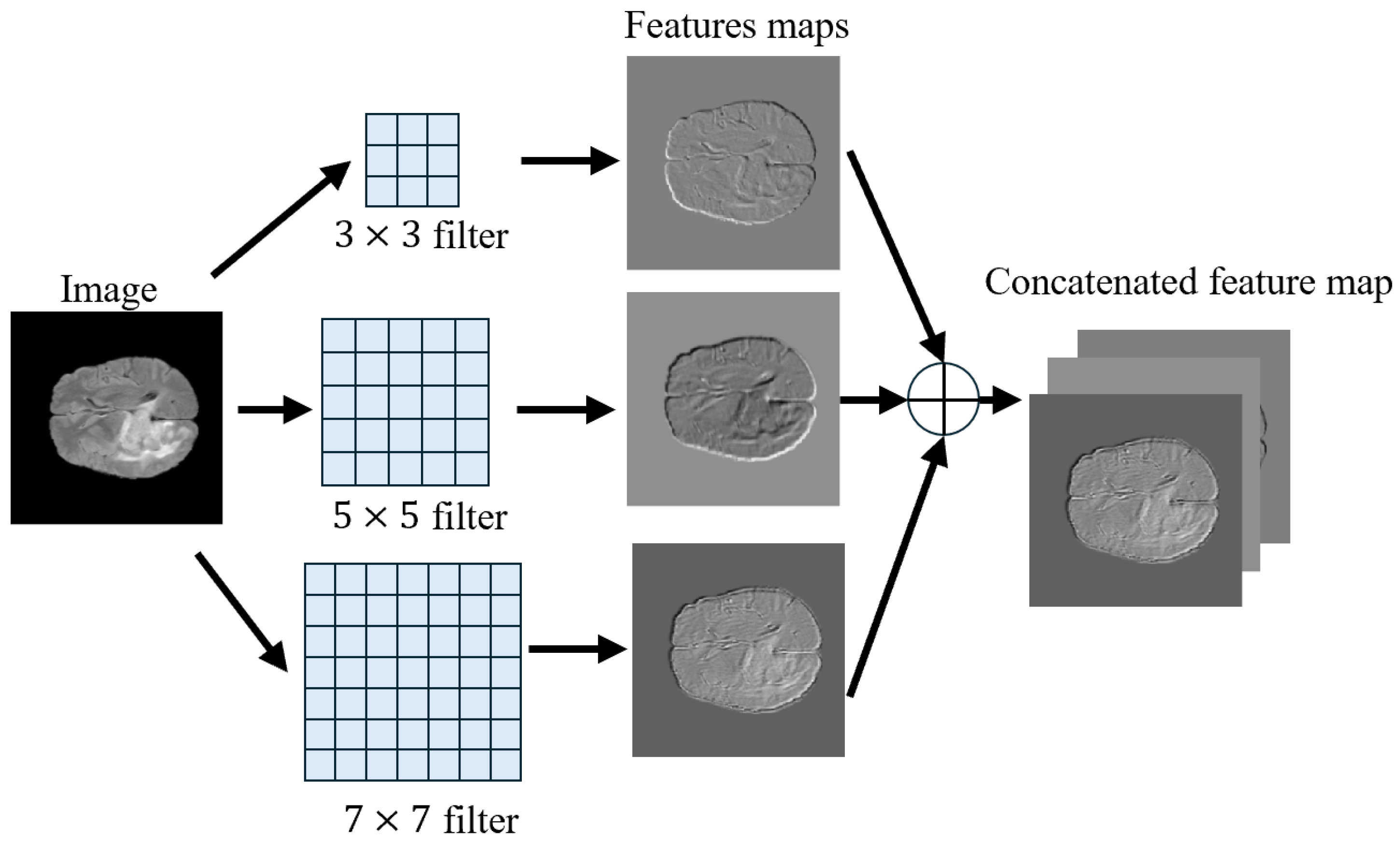

Figure 7.

Multi-scale feature extraction: The input image passes through three convolutional branches of size , , and . In addition, the feature maps are stacked into a fused feature map.

Figure 7.

Multi-scale feature extraction: The input image passes through three convolutional branches of size , , and . In addition, the feature maps are stacked into a fused feature map.

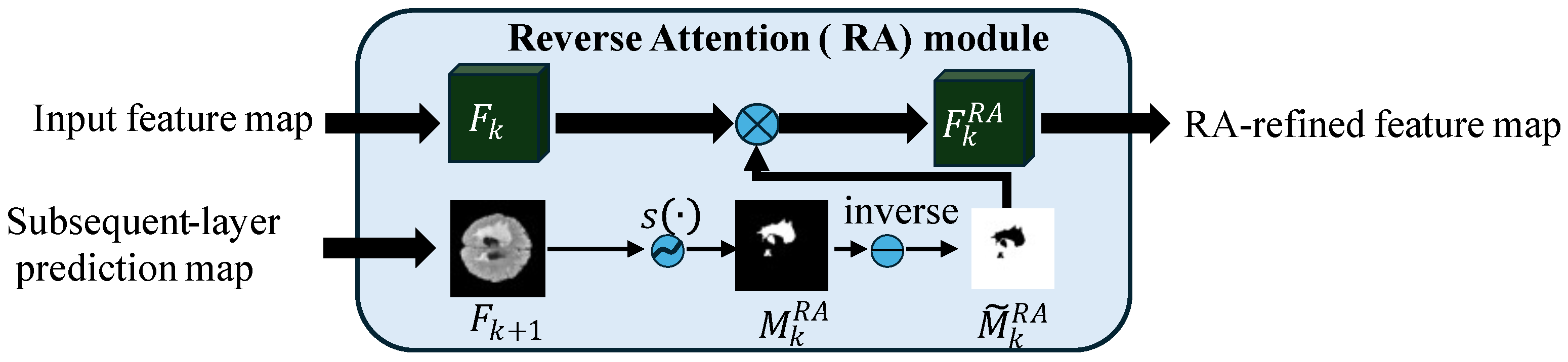

Figure 8.

Reverse Attention (RA) module [

64], where

and

are the feature maps at stages

k and

,

denotes the sigmoid function, ⊗ represents element-wise multiplication (Hadamard product), and

is the RA-refined feature map.

Figure 8.

Reverse Attention (RA) module [

64], where

and

are the feature maps at stages

k and

,

denotes the sigmoid function, ⊗ represents element-wise multiplication (Hadamard product), and

is the RA-refined feature map.

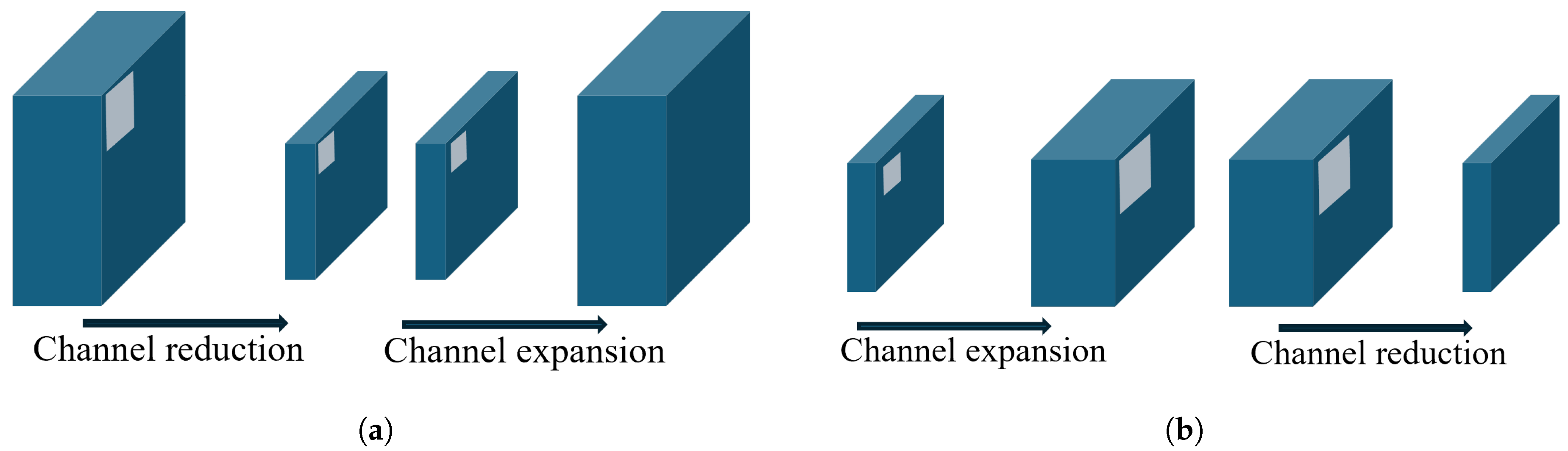

Figure 9.

Visual comparison of a ResNet-style residual bottleneck and an inverted bottleneck: (a) Residual bottleneck; (b) inverted bottleneck.

Figure 9.

Visual comparison of a ResNet-style residual bottleneck and an inverted bottleneck: (a) Residual bottleneck; (b) inverted bottleneck.

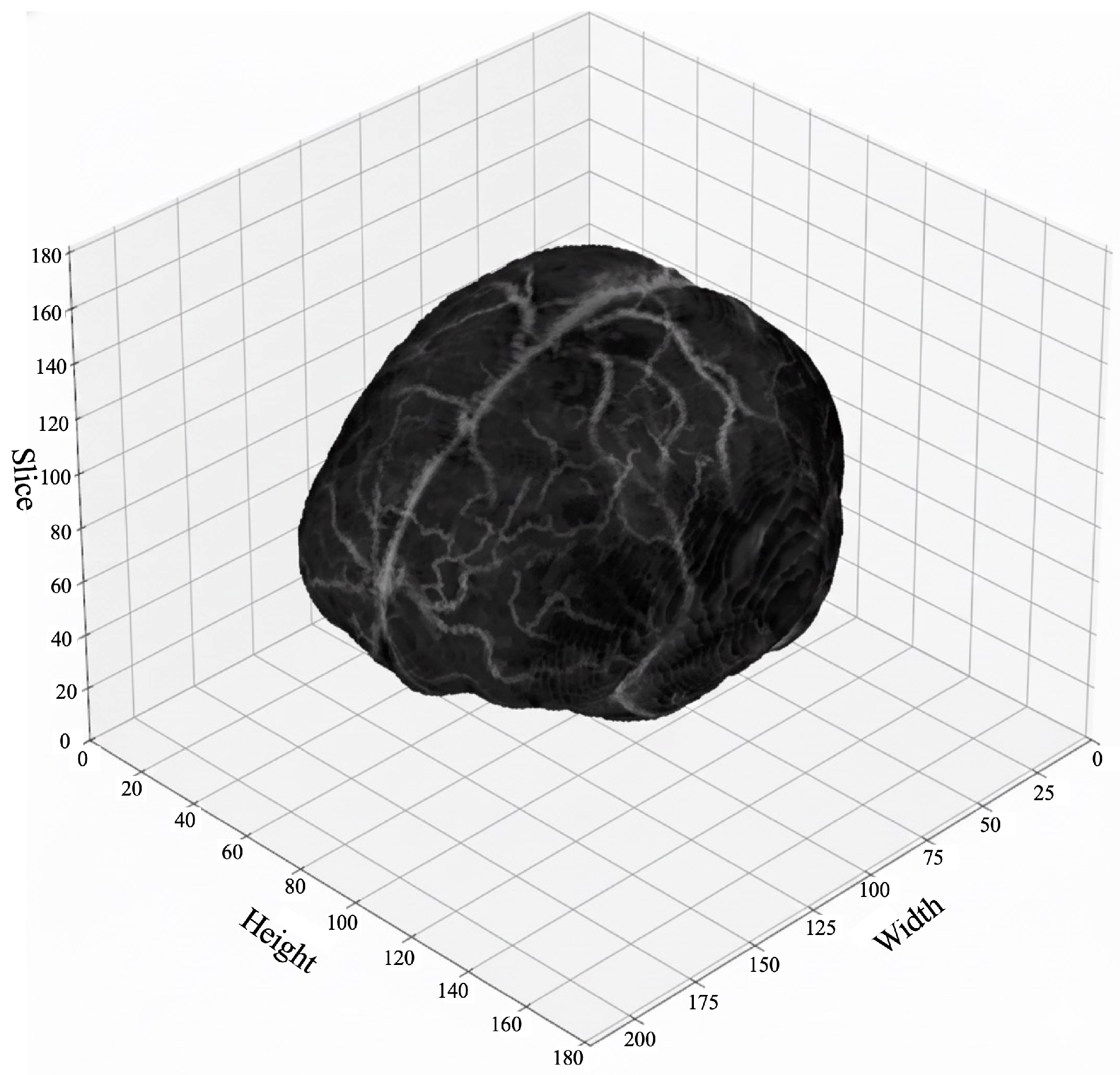

Figure 10.

Three-dimensional visualization of a BraTS T1-MRI volumetric image, showing the spatial distribution of anatomical structures across all slices.

Figure 10.

Three-dimensional visualization of a BraTS T1-MRI volumetric image, showing the spatial distribution of anatomical structures across all slices.

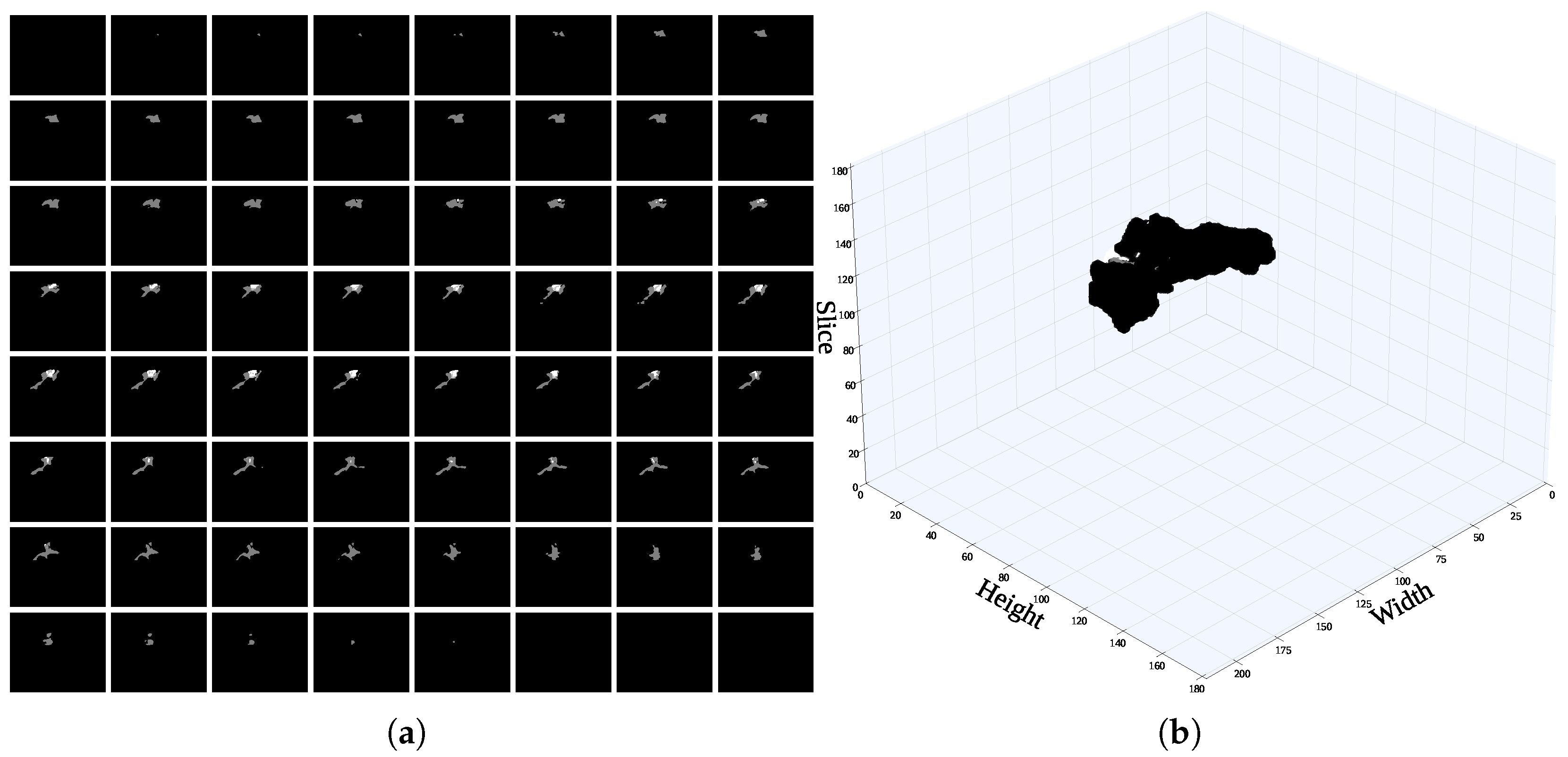

Figure 11.

A single voxel in the mask image comprises multiple slices, particularly those including sensitive information to (a) identify the slice containing the highest proportion of mask content. (b) 3D scatter visualization of the ground-truth mask.

Figure 11.

A single voxel in the mask image comprises multiple slices, particularly those including sensitive information to (a) identify the slice containing the highest proportion of mask content. (b) 3D scatter visualization of the ground-truth mask.

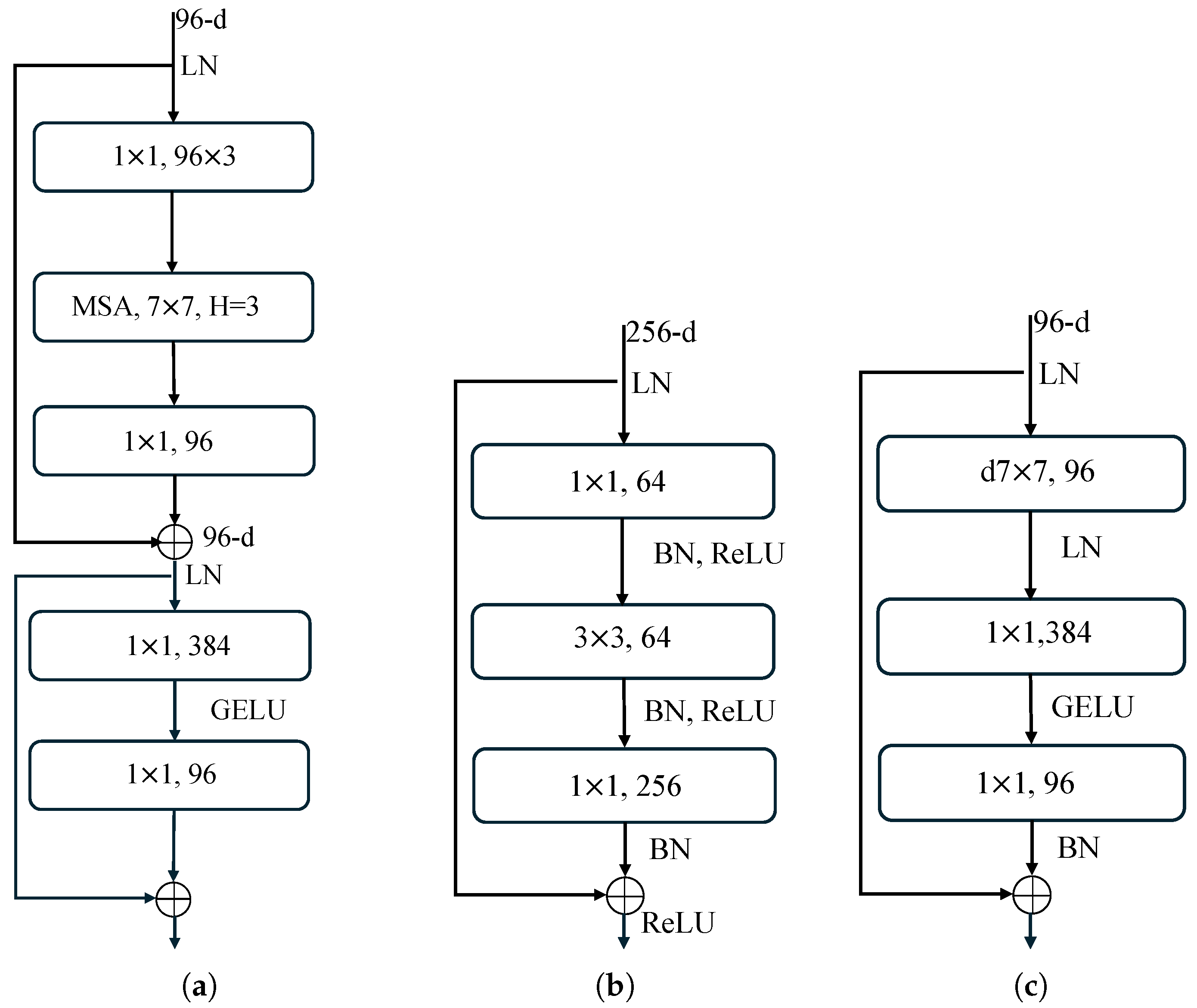

Figure 12.

Comparison of computational resource usage in Swin Transformer, ResNet, and ConvNeXt neural blocks. (a) Swin Transformer block; (b) ResNet block; (c) ConvNeXt block.

Figure 12.

Comparison of computational resource usage in Swin Transformer, ResNet, and ConvNeXt neural blocks. (a) Swin Transformer block; (b) ResNet block; (c) ConvNeXt block.

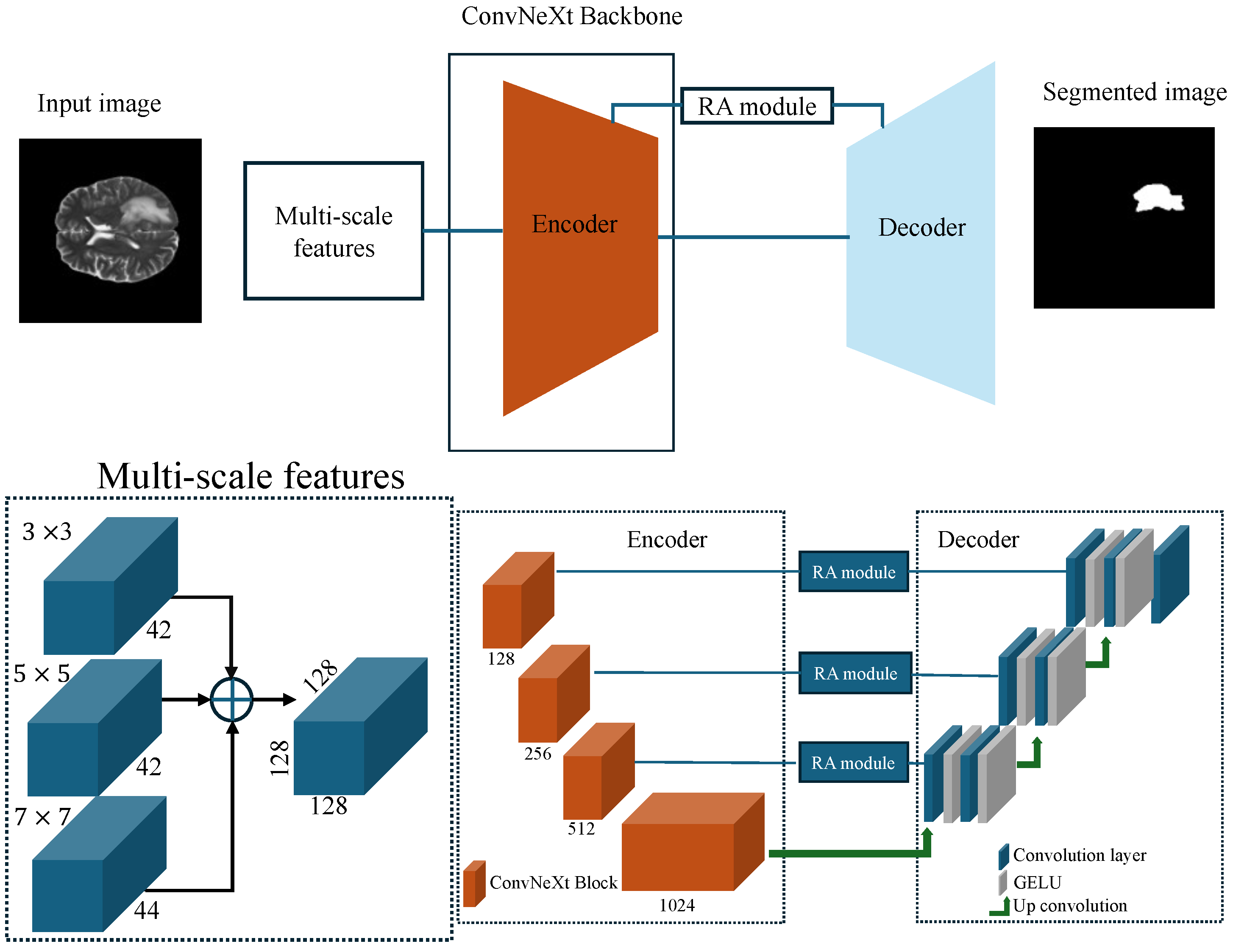

Figure 13.

Architecture of the proposed model, comprising a modified UNet with a ConvNeXt backbone, preceded by a multi-scale feature extraction module, and further enhanced with an RA module.

Figure 13.

Architecture of the proposed model, comprising a modified UNet with a ConvNeXt backbone, preceded by a multi-scale feature extraction module, and further enhanced with an RA module.

Figure 14.

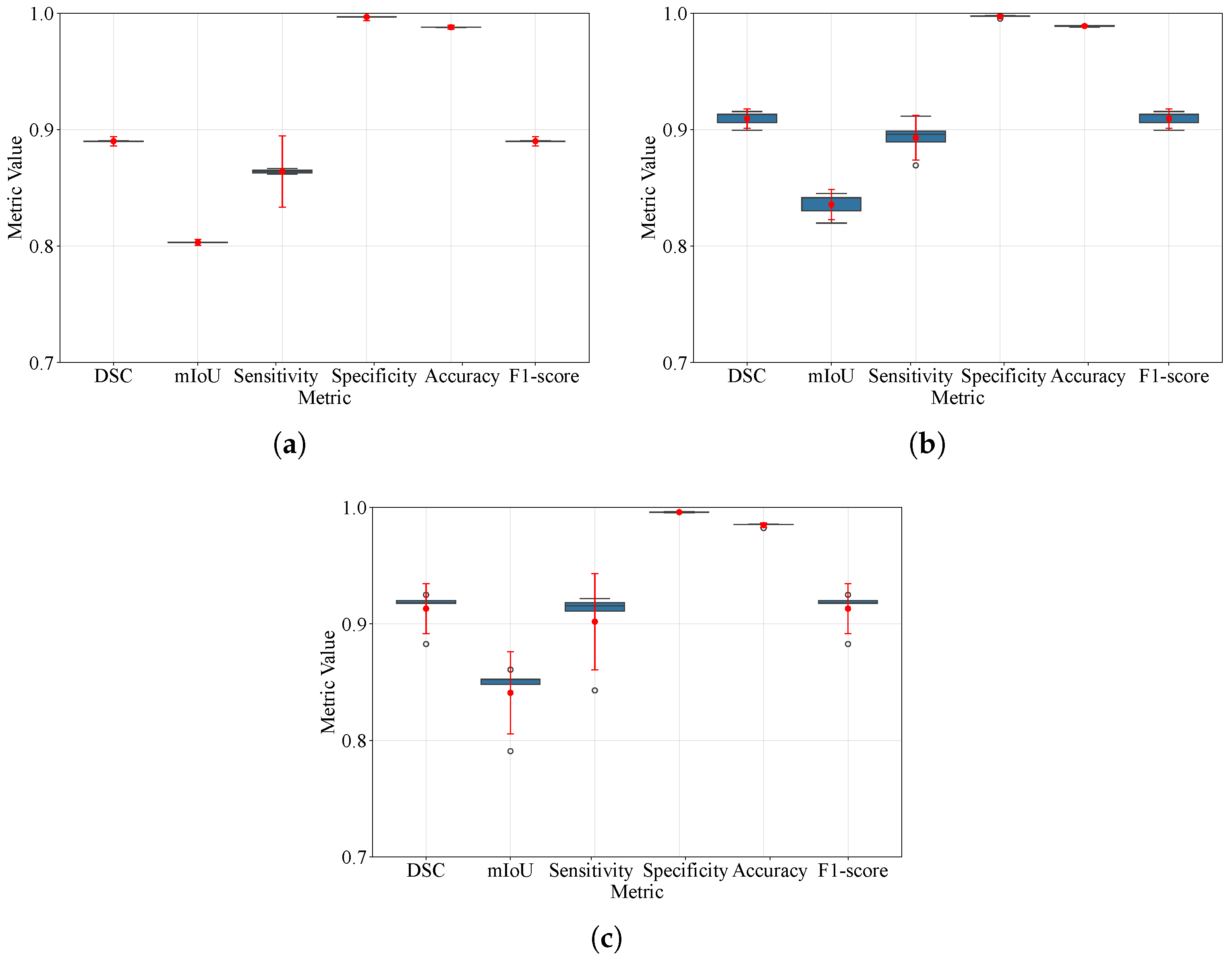

Box plots of DSC, IoU, sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and F1-score under 5-fold cross-validation for BraTS 2021, 2023, and 2024. Boxes depict the interquartile range with the median; whiskers indicate the range of non-outlier data per software defaults; and outliers are shown as individual points. Overlaid 95% confidence intervals summarize uncertainty across folds. (a) BraTS 2021; (b) BraTS 2023; (c) BraTS 2024. Hollow circles are the outliers IQR from the box and red dot is the arithmetic mean.

Figure 14.

Box plots of DSC, IoU, sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and F1-score under 5-fold cross-validation for BraTS 2021, 2023, and 2024. Boxes depict the interquartile range with the median; whiskers indicate the range of non-outlier data per software defaults; and outliers are shown as individual points. Overlaid 95% confidence intervals summarize uncertainty across folds. (a) BraTS 2021; (b) BraTS 2023; (c) BraTS 2024. Hollow circles are the outliers IQR from the box and red dot is the arithmetic mean.

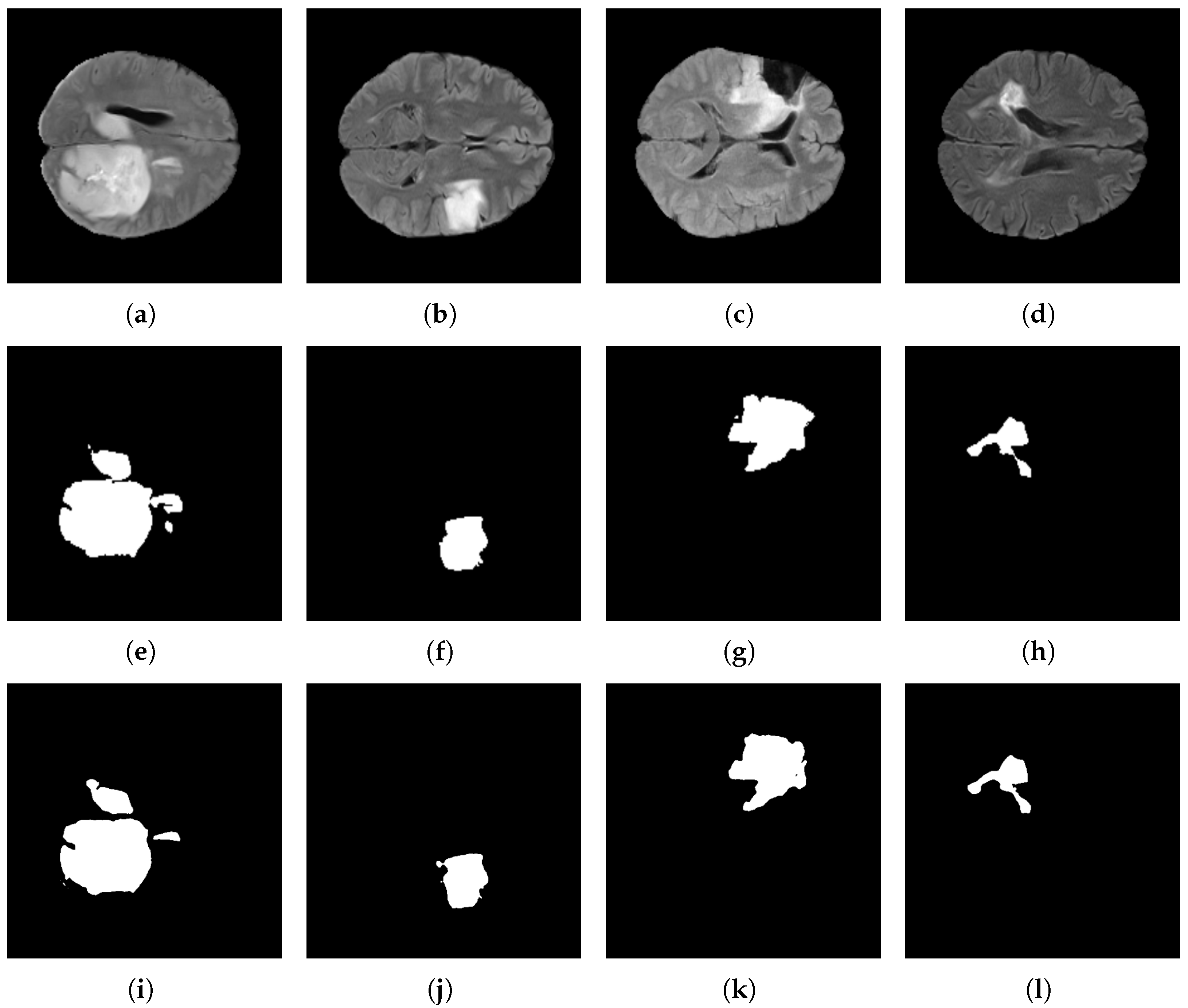

Figure 15.

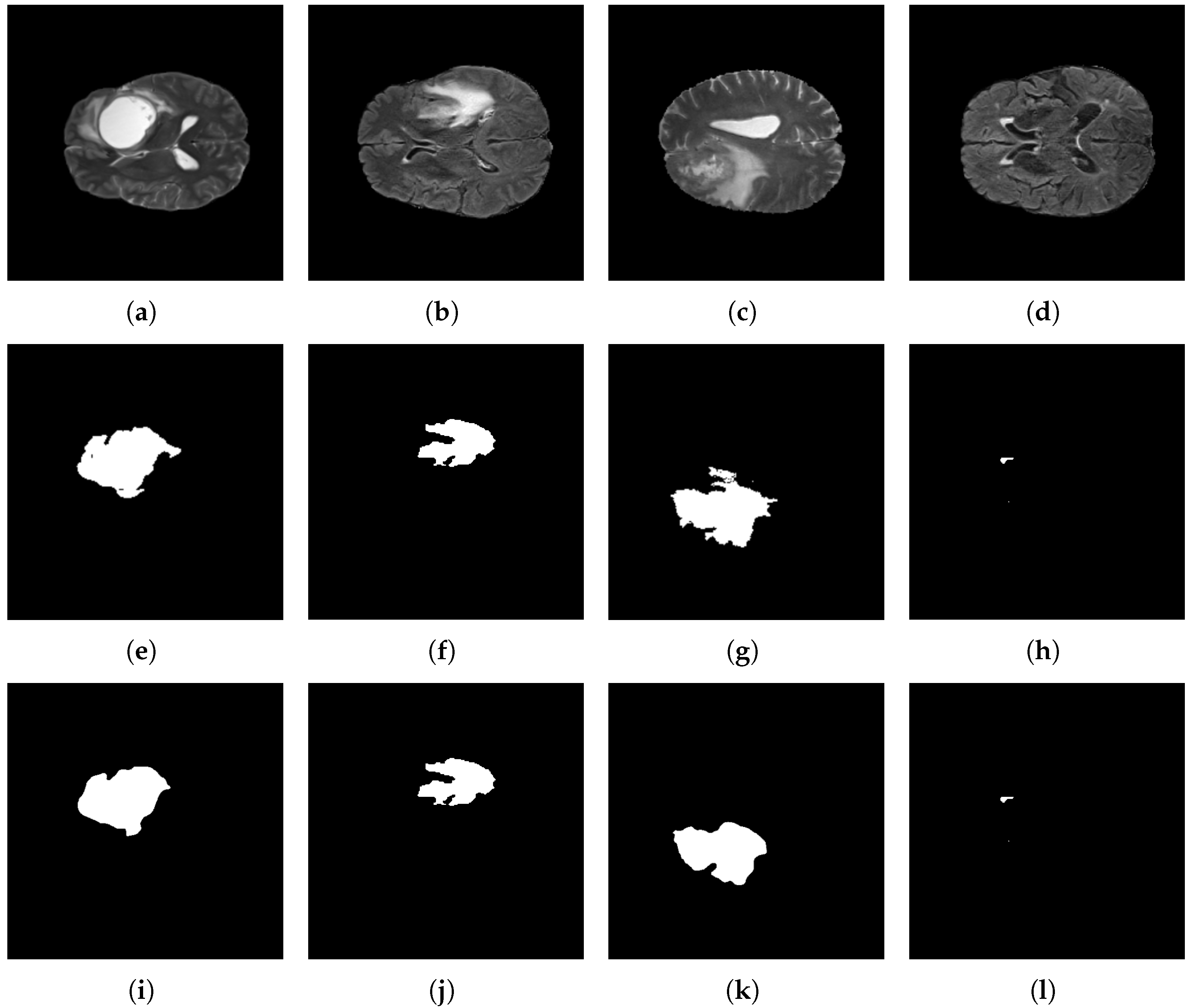

Brain tumor segmentation results using the BraTS 2021 dataset and the proposed architecture. Original images: (a–d); target images: (e–h); and predicted images: (i–l).

Figure 15.

Brain tumor segmentation results using the BraTS 2021 dataset and the proposed architecture. Original images: (a–d); target images: (e–h); and predicted images: (i–l).

Figure 16.

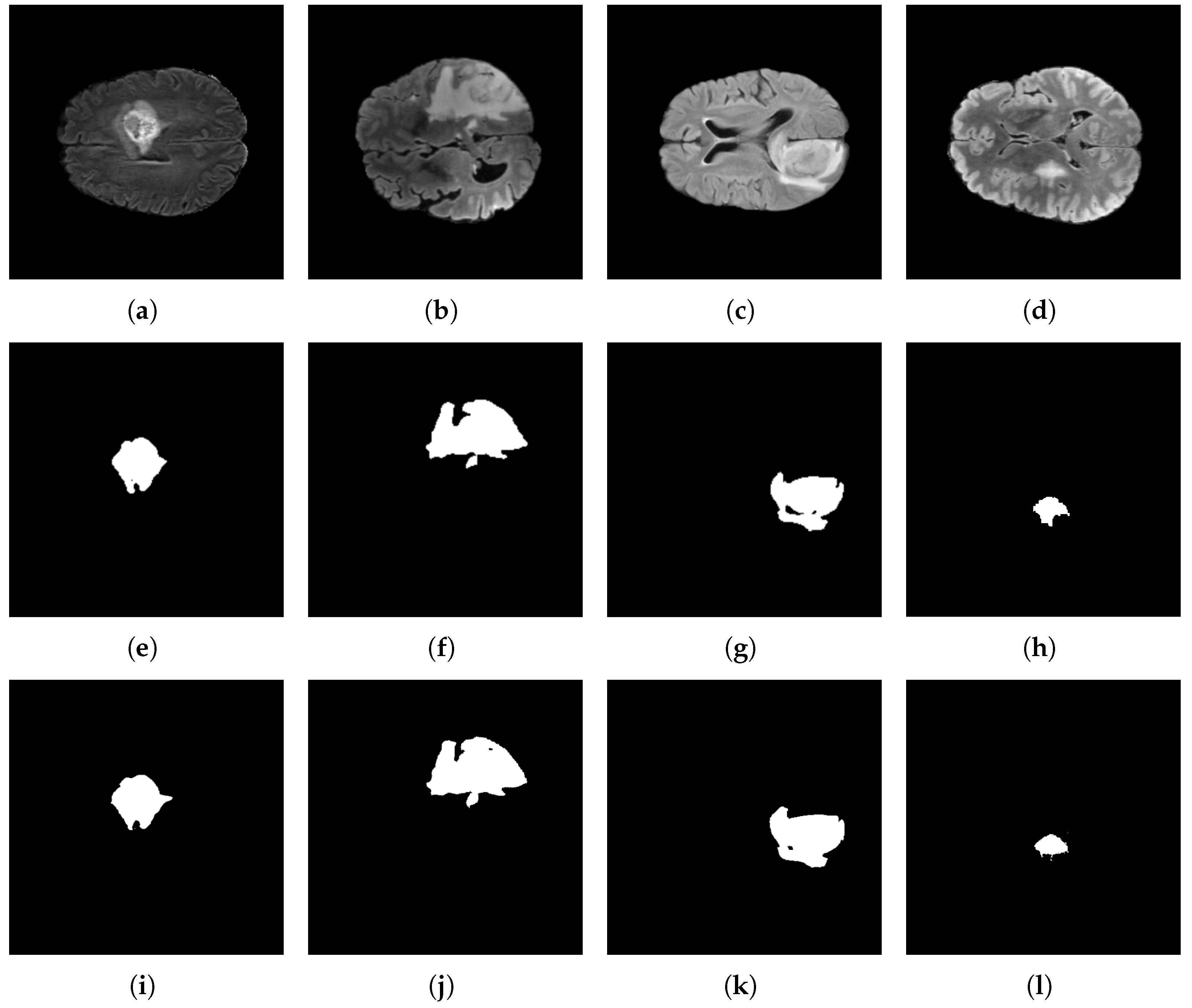

Brain tumor segmentation using the BraTS 2023 dataset and the proposed architecture. Original images: (a–d); target images: (e–h); and predicted images: (i–l).

Figure 16.

Brain tumor segmentation using the BraTS 2023 dataset and the proposed architecture. Original images: (a–d); target images: (e–h); and predicted images: (i–l).

Figure 17.

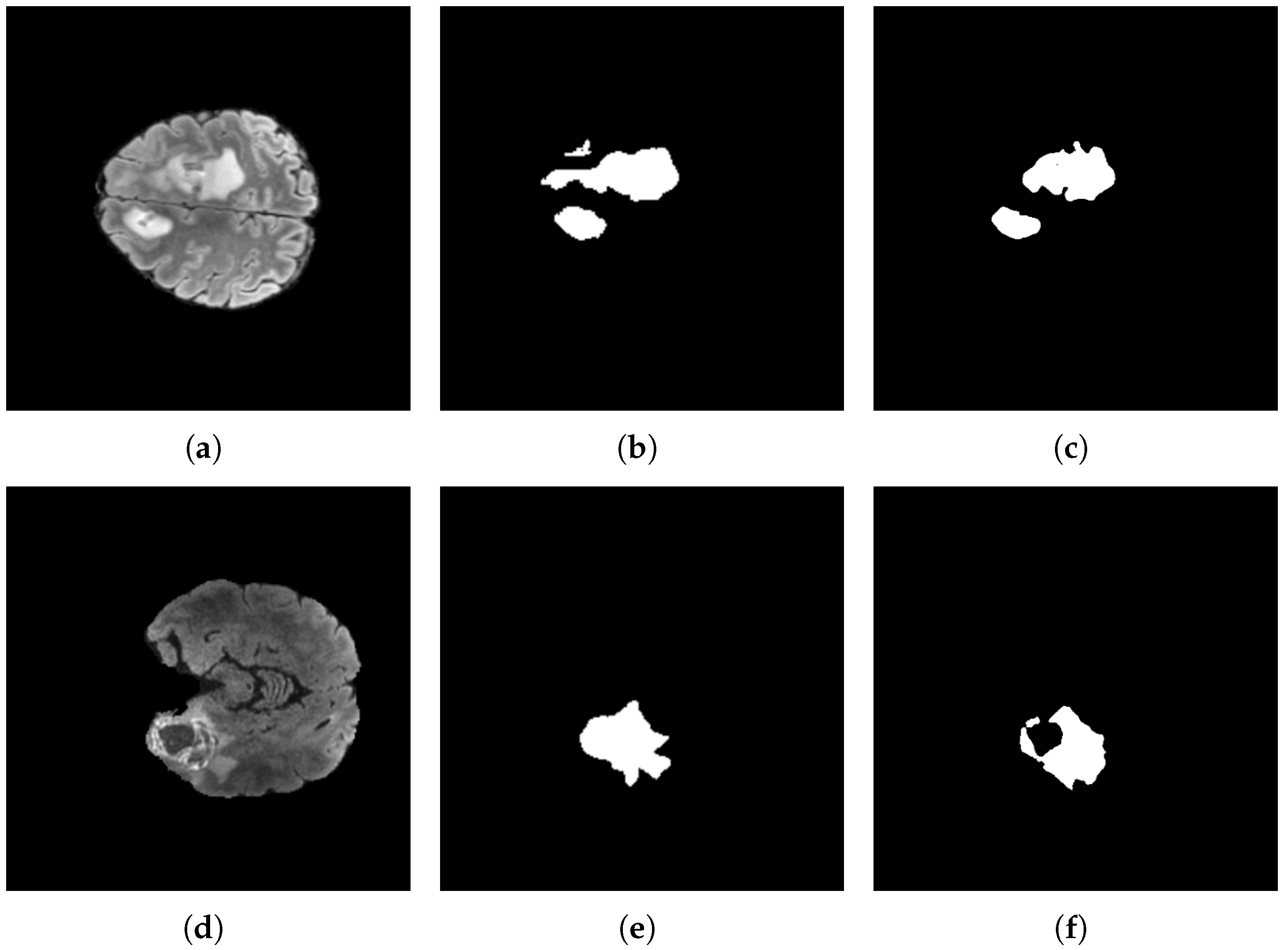

Exceptional cases where the model behaved poorly with the BraTS 2023 dataset with the proposed architecture. Original images: (a,d); target images: (b,e); and predicted images: (c,f).

Figure 17.

Exceptional cases where the model behaved poorly with the BraTS 2023 dataset with the proposed architecture. Original images: (a,d); target images: (b,e); and predicted images: (c,f).

Figure 18.

Brain tumor segmentation using the BraTS 2024 dataset and the proposed architecture. Original images: (a–d); target images: (e–h); and predicted images: (i–l).

Figure 18.

Brain tumor segmentation using the BraTS 2024 dataset and the proposed architecture. Original images: (a–d); target images: (e–h); and predicted images: (i–l).

Table 1.

Representative methods and datasets reported for brain tumor segmentation using Transformer models.

Table 1.

Representative methods and datasets reported for brain tumor segmentation using Transformer models.

| Article | Dataset | Method | Year |

|---|

| Andrade-Miranda et al. [33] | BraTS 2021 | Pure Versus Hybrid Transformer | 2022 |

| Chen and Yang [36] | BraTS 2021 | UNet-shaped Transformer with Convolutional | 2022 |

| Jia and Shu [37] | BraTS 2021 | CNN-Transformer Combined Network (BiTr-UNet) | 2022 |

| Jiang et al. [38] | BraTS 2021 | 3D Multimodal Brain Tumor Segmentation

Using Swin Transformer (SwinBTS) | 2022 |

| Dobko et al. [42] | BraTS 2021 | The Modified TransBTS | 2022 |

| Yang et al. [35] | BraTS 2021 | Convolution-and-Transformer Network (COTRNet) | 2022 |

| ZongRen et al. [39] | BraTS 2021 | DenseTrans using Swin Transformer | 2023 |

| Lin et al. [41] | BraTS 2021 | CKD-TransBTS | 2023 |

| Praveen et al. [40] | BraTS 2021 | 3D Swin-Res-SegNet | 2024 |

| Bhagyalaxmi and Dwarakanath [43] | BraTS 2023 | CDCG-UNet | 2025 |

| Asif et al. [52] | BraTS 2021 | TDAConvAttentionNet | 2025 |

Table 2.

A comparative analysis of the structural frameworks of each dataset, along with the corresponding image dimensions.

Table 2.

A comparative analysis of the structural frameworks of each dataset, along with the corresponding image dimensions.

| Dataset | Image | Training Set Size | Testing Set Size |

|---|

| BraTS 2021 [30] | | 277 | 120 |

| BraTS 2023 [31] | | 840 | 360 |

| BraTS 2024 [32] | | 840 | 360 |

Table 3.

Hyperparameter settings used in all experiments.

Table 3.

Hyperparameter settings used in all experiments.

| Hyperparameter | Value |

|---|

| Optimizer | AdamW |

| Learning rate | |

| Weight decay | |

| Loss | |

Table 4.

Averaged performance metrics obtained from three datasets.

Table 4.

Averaged performance metrics obtained from three datasets.

| Dataset | IoU | DSC | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | F1-Score |

|---|

| BraTS 2021 | 0.8200 | 0.9003 | 0.8836 | 0.9964 | 0.9881 | 0.9003 |

| BraTS 2023 | 0.8592 | 0.9235 | 0.9037 | 0.9977 | 0.9904 | 0.9235 |

| BraTS 2024 | 0.8575 | 0.9225 | 0.8989 | 0.9979 | 0.9903 | 0.9225 |

Table 5.

Comparison of different metrics for the Transformer models trained on the BraTS 2021 dataset.

Table 5.

Comparison of different metrics for the Transformer models trained on the BraTS 2021 dataset.

| Reference | IoU | DSC | HD | Sensitivity | Specificity | F1-Score |

|---|

| Andrade-Miranda et al. [33] | - | 0.896 | - | - | - | - |

| Chen and Yang [36] | - | 0.9335 | 2.8284 | - | - | - |

| Jia and Shu [37] | - | 0.9257 | - | - | - | - |

| Jiang et al. [38] | - | 0.9183 | 3.65 | - | - | - |

| Dobko et al. [42] | - | 0.8496 | 3.37 | - | - | - |

| Yang et al. [35] | - | 0.8392 | - | - | - | - |

| ZongRen et al. [39] | - | 0.932 | 4.58 | - | - | - |

| Lin et al. [41] | - | 0.933 | 6.20 | 0.9334 | - | - |

| UNet Baseline | 0.7465 | 0.8535 | 40.30 | 0.8061 | 0.9961 | 0.8535 |

| Proposed model | 0.8122 | 0.8956 | 33.038 | 0.8761 | 0.9964 | 0.8956 |

Table 6.

Comparison of different metrics for models trained on the BraTS 2023 dataset.

Table 6.

Comparison of different metrics for models trained on the BraTS 2023 dataset.

| Reference | IoU | DSC | HD | Sensitivity | Specificity | F1-Score |

|---|

| Nguyen-Tat et al. [75] | - | 0.8820 | - | - | - | - |

| Bhagyalaxmi and Dwarakanath [43] | - | 0.9930 | - | - | - | - |

| UNet baseline | 0.7423 | 0.8490 | 53.93 | 0.8313 | 0.9947 | 0.8490 |

| Our model | 0.8592 | 0.9235 | 26.7270 | 0.9037 | 0.9977 | 0.92356 |

Table 7.

Ablation study of different parameters on the BraTS datasets.

Table 7.

Ablation study of different parameters on the BraTS datasets.

| Dataset | Optimizer | | Loss Functions | | Evaluation Metrics |

|---|

|

Multi-Scale

|

BCE

|

DSC

|

RA

|

DSC

|

mIoU

|

Sensitivity

|

Specificity

|

Accuracy

|

F1-Score

|

HD

|

|---|

| BraTS 2021 | Adam | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.8924 | 0.8075 | 0.8749 | 0.9962 | 0.9875 | 0.8924 | 30.74 |

| Adam | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.8842 | 0.7983 | 0.8654 | 0.9959 | 0.9868 | 0.8842 | 54.44 |

| Adam | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | 0.8815 | 0.7951 | 0.8622 | 0.9958 | 0.9865 | 0.8815 | 31.62 |

| AdamW | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | 0.8956 | 0.8122 | 0.8761 | 0.9964 | 0.9878 | 0.8956 | 31.25 |

| AdamW | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.8867 | 0.8015 | 0.8689 | 0.9960 | 0.9870 | 0.8867 | 33.28 |

| AdamW | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.9003 | 0.8200 | 0.8836 | 0.9964 | 0.9881 | 0.9003 | 29.88 |

| BraTS 2023 | Adam | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | 0.9213 | 0.8551 | 0.9157 | 0.9968 | 0.9899 | 0.9213 | 30.53 |

| Adam | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.8845 | 0.8006 | 0.8648 | 0.9960 | 0.9870 | 0.8845 | 50.74 |

| Adam | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.8871 | 0.8024 | 0.9380 | 0.9928 | 0.9981 | 0.8871 | 30.89 |

| AdamW | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | 0.9078 | 0.8342 | 0.8929 | 0.9971 | 0.9893 | 0.9078 | 28.47 |

| AdamW | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.8931 | 0.8097 | 0.8710 | 0.9962 | 0.9876 | 0.8931 | 31.34 |

| AdamW | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.9235 | 0.8592 | 0.9037 | 0.9977 | 0.9904 | 0.9235 | 27.86 |

| BraTS 2024 | Adam | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | 0.8561 | 0.7499 | 0.8036 | 0.9962 | 0.9811 | 0.8561 | 25.65 |

| Adam | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.8610 | 0.7528 | 0.8084 | 0.9960 | 0.9815 | 0.8610 | 37.74 |

| Adam | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.9094 | 0.8347 | 0.9100 | 0.9956 | 0.9866 | 0.9094 | 22.97 |

| AdamW | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | 0.8483 | 0.7396 | 0.7787 | 0.9973 | 0.9808 | 0.8483 | 22.76 |

| AdamW | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.8519 | 0.7450 | 0.7855 | 0.9971 | 0.9810 | 0.8519 | 29.86 |

| AdamW | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0.9225 | 0.8575 | 0.8989 | 0.9979 | 0.9903 | 0.9225 | 19.60 |

Table 8.

Performance on BraTS 2021, 2023, and 2024 (mean ± standard deviation) over 5-fold cross-validation.

Table 8.

Performance on BraTS 2021, 2023, and 2024 (mean ± standard deviation) over 5-fold cross-validation.

| Dataset | DSC | mIoU | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | F1-Score | Hausdorff |

|---|

| BraTS 2021 | | | | | | | |

| BraTS 2023 | | | | | | | |

| BraTS 2024 | | | | | | | |

Table 9.

Mean voxel-wise epistemic uncertainty on the BraTS test set, stratified by prediction outcome.

Table 9.

Mean voxel-wise epistemic uncertainty on the BraTS test set, stratified by prediction outcome.

| Dataset | Outcome | Definition | Mean Uncertainty |

|---|

| BraTS 2024 | TP | Ground truth = 1, prediction = 1 | 0.00120 |

| FP | Ground truth = 0, prediction = 1 | 0.00880 |

| FN | Ground truth = 1, prediction = 0 | 0.01490 |

| TN | Ground truth = 0, prediction = 0 | 0.00260 |

| BraTS 2023 | TP | Ground truth = 1, prediction = 1 | 0.001330 |

| FP | Ground truth = 0, prediction = 1 | 0.004814 |

| FN | Ground truth = 1, prediction = 0 | 0.009376 |

| TN | Ground truth = 0, prediction = 0 | 0.001799 |

| BraTS 2021 | TP | Ground truth = 1, prediction = 1 | 0.003874 |

| FP | Ground truth = 0, prediction = 1 | 0.004664 |

| FN | Ground truth = 1, prediction = 0 | 0.003996 |

| TN | Ground truth = 0, prediction = 0 | 0.000601 |

Table 10.

Friedman test across BraTS 2021, BraTS 2023, and BraTS 2024 for the used segmentation metrics.

Table 10.

Friedman test across BraTS 2021, BraTS 2023, and BraTS 2024 for the used segmentation metrics.

| Metric | Friedman Statistic | p-Value |

|---|

| DSC | 4.0 | 0.1353 |

| mIoU | 4.0 | 0.1353 |

| Sensitivity | 3.0 | 0.2231 |

| Specificity | 4.0 | 0.1353 |

| Accuracy | 1.0 | 0.6065 |

| F1-score | 4.0 | 0.1353 |

Table 11.

Slice-level failure mode analysis stratified by tumor size on the BraTS 2021, 2023, and 2024 test sets. Tumor size is defined as the number of ground-truth tumor pixels per slice. For each dataset, small, medium, and large groups correspond to the lower, middle, and upper thirds of the tumor-size distribution, with thresholds set at the 33rd and 66th percentiles. The last column reports the mean number of large false-negative (FN) clusters per slice, where a large FN cluster is defined as a connected component containing at least 100 misclassified tumor pixels.

Table 11.

Slice-level failure mode analysis stratified by tumor size on the BraTS 2021, 2023, and 2024 test sets. Tumor size is defined as the number of ground-truth tumor pixels per slice. For each dataset, small, medium, and large groups correspond to the lower, middle, and upper thirds of the tumor-size distribution, with thresholds set at the 33rd and 66th percentiles. The last column reports the mean number of large false-negative (FN) clusters per slice, where a large FN cluster is defined as a connected component containing at least 100 misclassified tumor pixels.

| Dataset | Size Class | # Slices | Dice (Mean ± Std) | Mean # Large FN Clusters |

|---|

| BraTS 2021 | Small | 63 | 0.873 ± 0.100 | 1.79 |

| Medium | 62 | 0.908 ± 0.062 | 2.61 |

| Large | 64 | 0.919 ± 0.058 | 3.48 |

| BraTS 2023 | Small | 30 | 0.917 ± 0.048 | 1.43 |

| Medium | 30 | 0.926 ± 0.065 | 1.93 |

| Large | 31 | 0.956 ± 0.020 | 2.48 |

| BraTS 2024 | Small | 10 | 0.933 ± 0.026 | 1.70 |

| Medium | 10 | 0.946 ± 0.013 | 1.70 |

| Large | 10 | 0.925 ± 0.065 | 2.90 |

Table 12.

Computational efficiency analysis of the proposed model.

Table 12.

Computational efficiency analysis of the proposed model.

| Model | Parameters | FLOPs | Inference (Mean ± Std) |

|---|

| M = | G = | FPS | Latency (ms/Image) |

|---|

| UNet Baseline | 31.38 M | 97.70 G | 9.03 ± 0.3006 | 110.8895 ± 3.5383 |

| Proposed model | 100.38 M | 111.21 G | 59.92 ± 0.3485 | 16.8065 ± 0.0968 |