Design and Fabrication of a Compact Evaporator–Absorber Unit with Mechanical Enhancement for LiBr–H2O Vertical Falling Film Absorption, Part II: Control-Volume Modeling and Thermodynamic Performance Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

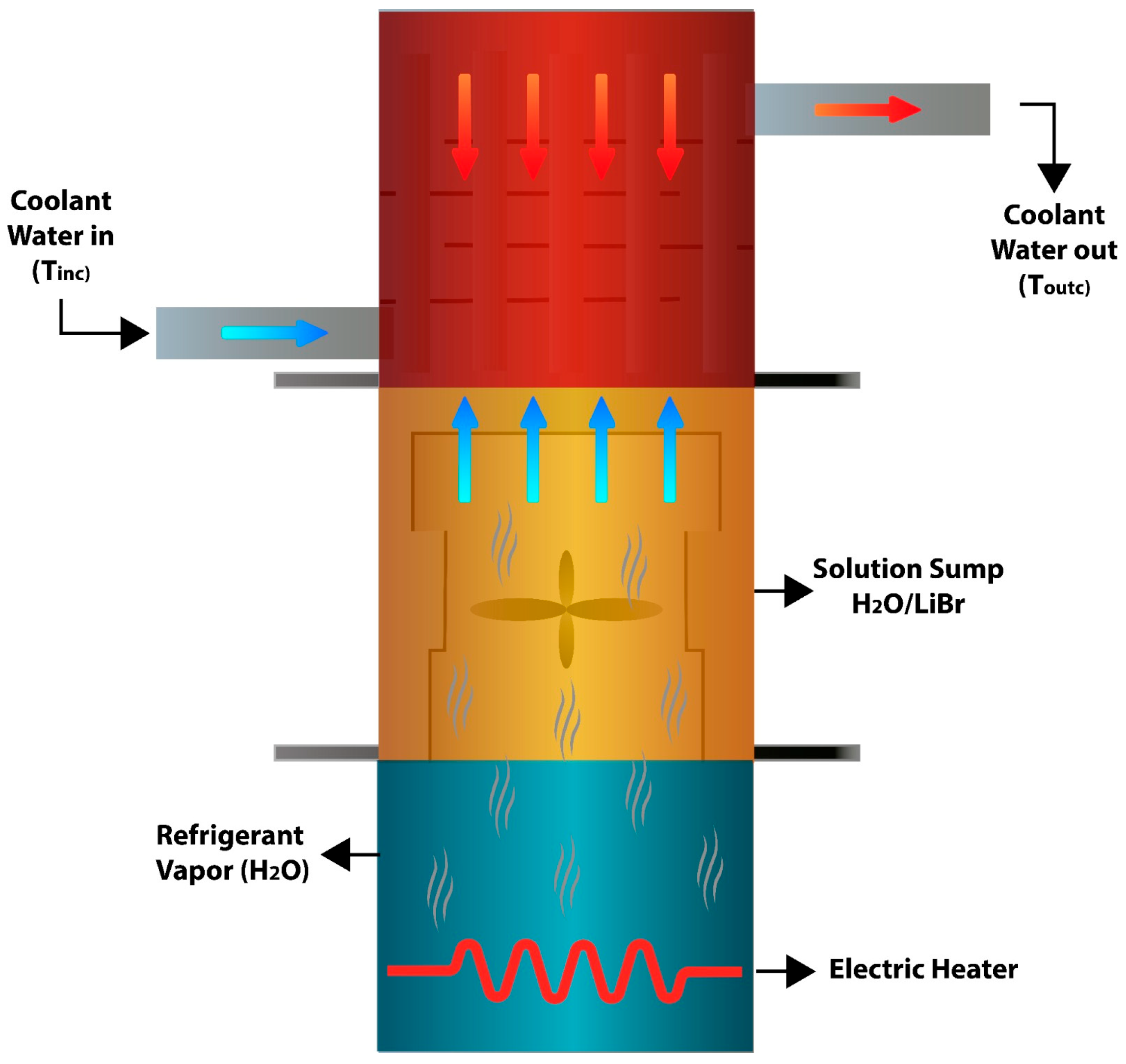

2.1. Experimental Platform Overview

2.2. Operating Protocol and Cycle Description

2.3. Rationale for Manual Load Adjustment and Data Clustering

- Group 1 (High loads): 219–223 W nominal input (Qin,1, Qin,6, Qin,10).

- Group 2 (Medium-high loads): 138–183 W nominal input (Qin,2, Qin,7, and Qin,11).

- Group 3 (Medium-low loads): 60–110 W (Qin,3, Qin,4, and Qin,8).

- Group 4 (Zero-input/passive baseline): three phases with Qin (Qin,5, Qin,9, Qin,12), used as an internal repeatability reference under identical boundary conditions. Here, “zero-input” refers strictly to the electrical heaters being switched off; any residual environmental heat exchange with the laboratory air is implicitly included in the measured signal and forms part of the passive baseline rather than being treated as a separate imposed load.

2.4. Control-Volume Formulation and Data Reduction

- Solution circuit:

- Refrigeration circuit:

- Coolant water circuit:

- Near-film properties. Solution enthalpies are inferred from near-film temperatures and literature correlations for ~60 wt.% LiBr–H2O introduce an estimated ±15% uncertainty in due to a possible enthalpy mismatch.

- Constant density. The density used to convert volumetric solution flow () to mass flow is treated as constant within the operating range, contributing an uncertainty of approximately ±5–10%.

- Constant latent heat. The latent heat of water vapor is taken as ; its temperature dependence contributes <0.1% to the overall uncertainty.

2.5. Uncertainty and Error Propagation

2.5.1. Measurement Uncertainties

2.5.2. Modeling Uncertainties

2.5.3. Propagation Method

2.5.4. Uncertainty in the Absorption Heat-Transfer Rate

2.5.5. Uncertainty in the Estimated Mass-Transfer Rate

2.5.6. Sensitivity of Slope Trends and Regime Classification to ±15% Enthalpy Uncertainty (Monte Carlo)

2.5.7. Uncertainty in the Global Thermal Resistance

3. Results

3.1. Dynamics of Absorption Heat Transfer () Under Variable Thermal Loads

- Performance stabilization (dominant). When fan-OFF operation shows a downward trend (), fan activation drives toward zero or positive values, indicating stabilization.

- Performance acceleration. When the baseline trend is already favorable (), the fan can amplify the improvement (e.g., Qin,2)

- Moderation under strong natural convection (atypical). In a limited number of high-load cases (Qin,6, Qin,10), the fan reduces the naturally positive slope, indicating a damping effect rather than a loss of viability.

3.2. Dynamics of Estimated Absorption Mass Transfer () Under Variable Thermal Loads

- Stabilize: If , turn the fan ON to stabilize quickly.

- Maintain: If , the fan helps preserve that quasi-steady state.

- Moderate: If is strongly positive at high loads, fan activation moderates growth to improve controllability.

3.3. Thermal Resistance () Analysis

- High thermal loads (Group 1, Figure 5a). Under high inputs (Qin,1, Qin,6, Qin,10) remains low in both operating modes (). This indicates that at high vapor-generation rates, buoyancy-driven transport is already dominant and the fan provides only an incremental benefit.

- Medium-to-low loads (Groups 2 and 3, Figure 5b,c). As the thermal load decreases, the influence of fan assistance becomes more apparent. values are moderately reduced with the fan ON, indicating improved dissipation capability when the natural ΔT driving force weakens. In the center panel of Figure 5b, the fan-ON and fan-OFF curves appear closely spaced because the intermediate heat-input level yields similar ΔT/Qabs ratios and therefore comparable values.

- Zero-input/passive loads (Group 4, Figure 5d). The most pronounced effect is observed in the absence of active heating (Qin,5, Qin,9, Qin,12). Fan operation significantly reduces , often by more than 30%, recovering a portion of the unit’s heat-dissipation capability under negligible buoyancy forces. This confirms the fan’s strong contribution in low-circulation regimes.

4. Discussion

4.1. Coupled Dynamics of Heat and Mass Transfer

4.2. Thermal Resistance Analysis and Technology Benchmarking

4.3. Operational Implications: From Stabilization to Control

- Stabilization mode (low/zero loads). When fan-OFF operation exhibits a negative slope (downward drift), forced convection becomes critical. Switching the fan ON attenuates the drift and brings the response toward a quasi-steady plateau, sustaining absorption capacity during weak-gradient regimes. This is the primary operating mode for reliability under intermittent use, low solar availability, or idle/standby periods.

- Acceleration mode (medium loads). In regimes where natural convection already produces a mild positive trend, fan activation acts as a dynamic accelerator, steepening the slope and shortening the transient time required to reach a useful operating level (e.g., +137% in Qin,2). This mode is valuable for rapid start-up and for responding promptly to load increases in decentralized cooling scenarios.

- Moderation mode (high loads). Under high thermal inputs, buoyancy-driven transport is strong, and the subsystem can exhibit rapid, high-sensitivity transients. In these cases, fan activation tends to moderate the slope, producing a damping-like trend response (i.e., smaller slope magnitude under fan-ON than fan-OFF) that preserves controllability. This regime-dependent moderation does not imply reduced viability; rather, it delineates an upper-load region where forced convection is better used as a stabilizing actuator than as a booster in the present apparatus and dataset.

- In the absence of local flow diagnostics (e.g., vapor-velocity measurements, spatial pressure-gradient mapping, or film-thickness/interface imaging), this moderation is interpreted at the response level rather than claimed as a proven fluid-dynamic mechanism. A plausible first-order explanation consistent with the observed trend-level behavior is that, at high loads, the coupled buoyancy-driven vapor transport and absorption heat release can approach a transport-limited condition in which additional forced circulation primarily redistributes gradients and enhances mixing in the vapor core (chimney region), reducing the effective sensitivity of the absorber-side response to further thermal driving. In this regime, the fan may therefore act as an internal actuator that damps transient sensitivity by smoothing the coupled heat/mass-transfer feedback, rather than increasing the net driving potential. Confirming the detailed mechanism would require dedicated flow-field and interface diagnostics, which are outside the scope of the present instrumentation and are identified as future work.

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Phase-Resolved Expanded Uncertainties

| Phase Qin,k | Fan | N | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Off | 174 | 0.367423 | 19.942241 | 0.028613 | 0.002652 |

| 1 | On | 284 | 0.367423 | 16.417964 | 0.021483 | 0.003505 |

| 2 | Off | 358 | 0.367423 | 19.708780 | 0.025705 | 0.003010 |

| 2 | On | 347 | 0.367423 | 29.141165 | 0.037803 | 0.002191 |

| 3 | Off | 383 | 0.367423 | 17.340115 | 0.022851 | 0.003690 |

| 3 | On | 270 | 0.367423 | 15.339036 | 0.020099 | 0.004015 |

| 4 | Off | 301 | 0.367423 | 12.818685 | 0.016903 | 0.004663 |

| 4 | On | 355 | 0.367423 | 11.611687 | 0.015319 | 0.004938 |

| 5 | Off | 426 | 0.367423 | 10.776648 | 0.014249 | 0.005343 |

| 5 | On | 997 | 0.367423 | 7.187841 | 0.009644 | 0.009088 |

| 6 | Off | 396 | 0.367423 | 9.621396 | 0.012362 | 0.005475 |

| 6 | On | 346 | 0.367423 | 17.415127 | 0.022762 | 0.002567 |

| 7 | Off | 305 | 0.367423 | 16.120900 | 0.021151 | 0.000017 |

| 7 | On | 294 | 0.367423 | 15.524080 | 0.020337 | 0.000009 |

| 8 | Off | 293 | 0.367423 | 13.574729 | 0.018110 | 0.003102 |

| 8 | On | 302 | 0.367423 | 13.036188 | 0.017148 | 0.003113 |

| 9 | Off | 370 | 0.367423 | 8.526518 | 0.011354 | 0.004722 |

| 9 | On | 1209 | 0.367423 | 7.119081 | 0.009552 | 0.007896 |

| 10 | Off | 418 | 0.367423 | 10.462230 | 0.011099 | 0.003946 |

| 10 | On | 248 | 0.367423 | 15.697957 | 0.020557 | 0.002103 |

| 11 | Off | 340 | 0.367423 | 14.788821 | 0.019376 | 0.002042 |

| 11 | On | 453 | 0.367423 | 14.657124 | 0.019219 | 0.002056 |

| 12 | Off | 311 | 0.367423 | 9.689035 | 0.012848 | 0.002850 |

| 12 | On | 808 | 0.367423 | 7.707146 | 0.010307 | 0.005725 |

References

- Gu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Ke, X. Experimental research on a new solar pump-free lithium bromide absorption refrigeration system with a second generator. Sol. Energy 2008, 82, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.L.; Zhai, X.Q.; Wang, R.Z. Experimental investigation and performance analysis of a mini-type solar absorption cooling system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2013, 59, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.Q.; Qu, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, R.Z. A review for research and new design options of solar absorption cooling systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 4416–4423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.Y.; Wang, R.Z.; Wang, H.B. Experimental evaluation of a variable effect LiBr–water absorption chiller designed for high-efficient solar cooling system. Int. J. Refrig. 2015, 59, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Rivera, E.; Castro, J.; Farnos, J.; Oliva, A. Numerical and experimental investigation of a vertical LiBr falling film absorber considering wave regimes and in presence of mist flow. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2016, 109, 342–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, F.L.; Eleiwi, M.A.; Mohammed, H.I.; Ameen, A.; Ahmad, S. A Review of Using Solar Energy for Cooling Systems: Applications, Challenges, and Effects. Energies 2023, 16, 8075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alobaid, M.; Hughes, B.; Calautit, J.K.; O’Connor, D.; Heyes, A. A review of solar driven absorption cooling with photovoltaic thermal systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 76, 728–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florides, G.A.; Kalogirou, S.A.; Tassou, S.A.; Wrobel, L.C. Design and construction of a LiBr–water absorption machine. Energy Convers. Manag. 2003, 44, 2483–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaris, C.; Valles, M.; Bourouis, M. Vapour absorption enhancement using passive techniques for absorption cooling/heating technologies: A review. Appl. Energy. 2018, 231, 826–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, S.; Alvarado, J.L.; Hassan, I.G.; Kadam, S.T. A comprehensive review of recent developments in falling-film, spray, bubble and microchannel absorbers for absorption systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 142, 110807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panahizadeh, F.; Hamzehei, M.; Farzaneh-Gord, M.; Ochoa-Villa, A.A. Numerical study on heat and mass transfer behavior of pool boiling in LiBr/H2O absorption chiller generator considering different tube surfaces. Therm. Sci. 2021, 25, 1599–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.I.; Kwon, O.K.; Bansal, P.K.; Moon, C.G.; Lee, H.S. Heat and mass transfer characteristics of a small helical absorber. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2006, 26, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.K.; Park, C.W.; Kang, Y.T. The effect of micro-scale surface treatment on heat and mass transfer performance for a falling film H2O/LiBr absorber. Int. J. Refrig. 2003, 26, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourshad, H.; Mohammadi, M.; Vakilipour, S.; Rahmati, R. Enhancement of vapor absorption in LiBr falling film on the sinusoidal wall of cooling water channel: A fully-coupled approach. Int. J. Refrig. 2025, 178, 501–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Zeng, M.; Xu, R.; Xie, G.; Chu, W. Investigation on mass transfer characteristics of the falling film absorption of LiBr aqueous solution added with nanoparticles. Int. J. Refrig. 2018, 89, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Fu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Jin, L.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, W. Experimental study on enhancement of falling film absorption process by adding various nanoparticles. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 92, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, A.; Sarafraz, M.M.; Shahmiri, S.; Madani, S.A.H.; Nikkhah, V.; Nakhjavani, S.M. Thermal performance analysis of a flat heat pipe working with carbon nanotube-water nanofluid for cooling of a high heat flux heater. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 54, 985–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakoryakov, V.E.; Grigoryeva, N.I.; Bufetov, N.S.; Dekhtyar, R.A. Heat and mass transfer intensification at steam absorption by surfactant additives. Int. J. Heat Mass Trasnsf. 2008, 51, 5175–5181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hihara, E.; Saito, T. Effect of surfactant on falling film absorption. Int. J. Refrig. 1993, 16, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daiguji, H.; Hihara, E.; Saito, T. Mechanism of absorption enhancement by surfactant. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1997, 40, 1743–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, H.; Perez-Blanco, H. An experimental study of a vibrating screen as means of absorption enhancement. Int. J. Heat Mass Trasnsf. 2001, 44, 4087–4094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarafraz, M.M.; Nikkhah, V.; Madani, S.A.; Jafarian, M.; Hormozi, F. Low-frequency vibration for fouling mitigation and intensification of thermal performance of a plate heat exchanger working with CuO/water nanofluid. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 121, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Dong, C.; Qi, R. Numerical and experimental research on thickness fluctuation and Marangoni effect of falling film heat&mass transfer: A comprehensive review. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2023, 273, 118616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olvera Olvera, C.A.; Díaz Flórez, G.; Morales Oviedo, E.D.; Gómez Meléndez, D.J.; Araiza Esquivel, M.A.; Espinoza García, G. Módulo Evaporador/Absorbedor para Sistemas de Refrigeración por Absorción. Mexican Utility-Model. Application No. MX/u/2018/000306, 25 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Flórez, G.; Olvera-Olvera, C.A.; Villagrana-Barraza, S.; Solís-Sánchez, L.O.; Guerrero-Osuna, H.A.; Ibarra-Pérez, T.; Jaramillo Martínez, R.; Correa-Aguado, H.C.; Díaz-Flórez, G. Design and Fabrication of a Compact Evaporator–Absorber Unit with Mechanical Enhancement for LiBr–H2O Vertical Falling-Film Absorption, Part I: Experimental Validation. Technologies 2025, 13, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killion, J.D.; Garimella, S. A critical review of models of coupled heat and mass transfer in falling-film absorption. Int. J. Refrig. 2001, 24, 755–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Wijeysundera, N.E.; Ho, J.C. Evaluation of heat and mass transfer coefficients for falling-films on tubular absorbers. Int. J. Refrig. 2003, 26, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sow, M.; Grosu, L. Energy and Exergy Assessment of a Solar Driven Single Effect H2O-LiBr Absorption Chiller Under Moderate and Hot Climatic Conditions. Energies 2025, 18, 4553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.T.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, K.I. Heat and mass transfer enhancement of binary nanofluids for H2O/LiBr falling film absorption process. Int. J. Refrig. 2008, 31, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K.; Koo, J.; Hong, H.; Kang, Y.T. he effects of nanoparticles on absorption heat and mass transfer performance in NH3/H2O binary nanofluids. Int. J. Refrig. 2010, 33, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE. Psychrometrics. In ASHRAE Handbook—Fundamentals, SI ed.; Owen, M.S., Ed.; ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2017; pp. 1.1–1.40. [Google Scholar]

- Pátek, J.; Klomfar, J. A computationally effective formulation of the thermodynamic properties of LiBr–H2O solutions from 273 to 500 K over full composition range. Int. J. Refrig. 2006, 29, 566–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Gil, A.; Izquierdo, M.; Marcos, J.D.; Palacios, E. Experimental evaluation of a direct air-cooled lithium bromide–water absorption prototype for solar air conditioning. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2011, 31, 3358–3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Qian, Z.; Yao, Z.; Gan, N.; Zhang, Y. Thermodynamic evaluation of LiCl-H2O and LiBr-H2O absorption refrigeration systems based on a novel model and algorithm. Energies 2019, 12, 3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, J.; Ayou, D.S.; Coronas, A. A Novel H2O/LiBr Absorption Heat Pump with Condensation Heat Recovery for Combined Heating and Cooling Production: Energy Analysis for Different Applications. Clean Technol. 2022, 5, 51–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, Y.R.; Dutra, J.C.C.; Rohatgi, J. Thermodynamic modelling of a LiBr-H2O absorption chiller by improvement of characteristic equation method. Int. J. Refrig. 2020, 120, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, M.; Nasr Isfahani, R.; Bigham, S.; Moghaddam, S. Absorption characteristics of falling film LiBr solution over a finned structure. Energy 2015, 87, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isfahani, R.N.; Moghaddam, S. Absorption characteristics of lithium bromide (LiBr) solution constrained by superhydrophobic nanofibrous structures. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2013, 63, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrano, M.; Bourouis, M.; Coronas, A. Absorption of water vapour in the falling film of water–lithium bromide inside a vertical tube at air-cooling thermal conditions. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2002, 41, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.L.; Song, Z.P.; Li, Y.; Wang, R.Z.; Zhai, X.Q. Experimental investigation of a mini-type solar absorption cooling system under different cooling modes. Energy Build. 2012, 47, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R. Absorption process of a falling film on a tubular absorber: An experimental and numerical study. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2008, 28, 1386–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.J.F.; Shigang, Z. Experimental study on vertical vapor absorption into LiBr solution with and without additive. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2011, 31, 2850–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Wijeysundera, N.E.; Ho, J.C. Performance study of a falling-film absorber with a film-inverting configuration. Int. J. Refrig. 2003, 26, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, E.; Izquierdo, M.; Marcos, J.D.; Lizarte, R. Evaluation of mass absorption in LiBr flat-fan sheets. Appl. Energy 2009, 86, 2574–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, S.; Farhanieh, B. A numerical study on the absorption of water vapor into a film of aqueous LiBr falling along a vertical plate. Heat Mass Transf. 2009, 46, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; He, L.; He, Y. Review on absorption refrigeration technology and its potential in energy-saving and carbon emission reduction in natural gas and hydrogen liquefaction. Energies 2024, 17, 3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcântara, S.C.S.; da Costa, J.Â.P.; Ochoa, A.A.V.; Leite, G.D.N.P.; Lima, Á.A.S.; Silva, H.C.N.; Michima, P.S.A.; da Silveira, I.C.; de Araujo Caldas, A.M.; Altamirano, A. Critical Review of Advances and Numerical Modeling in Absorbers and Desorbers of Absorption Chillers: CFD Applications, Constraints, and Future Prospects. Energies 2025, 18, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Yu, L.; Tang, X.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; He, Z. Multi-objective optimization of a hydrogen-fueled PEMFC with multi wavy channels via machine learning and CFD simulation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2026, 199, 152748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measured Variable | Instrument/Sensor | Uncertainty (±) | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (T) | OMEGA TC-K-NPT-U-72 thermocouples | 0.3 | °C |

| Pressure (P) | OMEGA PX309-015AI transducers | 1.0 | % of FS |

| Flow rate (coolant water) | YF-S201 hall-effect sensor | 10.0 | % |

| Voltage and current | DC power Supply + DAQ (OPTO22 SNAP-PAC-R1) | 0.5 | % |

| (water, LiBr) | Literature values (assumed constant) | 2.0 | % (est.) |

| Cross-sectional area (A) | CAD measurement of internal geometry | 1.0 | % (est.) |

| Thermal Load | s−1) | s−1) | Relative Improvement of a (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qin,1 | −0.67 | 0.01 | |

| Qin,2 | 0.30 | 0.71 | |

| Qin,3 | −0.49 | 0.07 | |

| Qin,4 | −0.14 | 0.05 | |

| Qin,5 | −0.28 | −0.04 | |

| Qin,6 | 0.52 | 0.09 | |

| Qin,7 | −0.12 | 0.02 | |

| Qin,8 | −0.17 | −0.08 | |

| Qin,9 | −0.22 | −0.02 | |

| Qin,10 | 0.42 | 0.12 | |

| Qin,11 | −0.02 | 0.01 | |

| Qin,12 | −0.41 | −0.03 |

| Thermal Load | ) | ) | Relative Improvement of b (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qin,1 | |||

| Qin,2 | |||

| Qin,3 | |||

| Qin,4 | |||

| Qin,5 | |||

| Qin,6 | |||

| Qin,7 | |||

| Qin,8 | |||

| Qin,9 | |||

| Qin,10 | |||

| Qin,11 | |||

| Qin,12 |

| Thermal Load | NOFF | NON | Wilcoxon p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qin,1 | 174 | 284 | 0.09818 | 0.05738 | <1 × 10−6 |

| Qin,2 | 358 | 347 | 0.08225 | 0.04663 | <1 × 10−6 |

| Qin,3 | 383 | 270 | 0.04551 | 0.02738 | <1 × 10−6 |

| Qin,4 | 301 | 355 | 0.02443 | 0.01887 | <1 × 10−6 |

| Qin,5 | 426 | 997 | 0.02459 | 0.01565 | <1 × 10−6 |

| Qin,6 | 396 | 346 | 0.03219 | 0.02507 | 0.001 |

| Qin,7 | 305 | 294 | 0.03866 | 0.03323 | 0.081 |

| Qin,8 | 293 | 302 | 0.04655 | 0.04062 | 0.066 |

| Qin,9 | 370 | 1209 | 0.15470 | 0.12918 | 0.014 |

| Qin,10 | 418 | 248 | 0.13670 | 0.11487 | 0.038 |

| Qin,11 | 340 | 453 | 0.13017 | 0.11805 | 0.054 |

| Qin,12 | 311 | 808 | 0.14897 | 0.12945 | 0.021 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Díaz-Flórez, G.; Ibarra-Pérez, T.; Olvera-Olvera, C.A.; Villagrana-Barraza, S.; Araiza-Esquivel, M.A.; Guerrero-Osuna, H.A.; Jaramillo-Martínez, R.; Torres-Hernández, M.A.; Díaz-Flórez, G. Design and Fabrication of a Compact Evaporator–Absorber Unit with Mechanical Enhancement for LiBr–H2O Vertical Falling Film Absorption, Part II: Control-Volume Modeling and Thermodynamic Performance Analysis. Technologies 2026, 14, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14010033

Díaz-Flórez G, Ibarra-Pérez T, Olvera-Olvera CA, Villagrana-Barraza S, Araiza-Esquivel MA, Guerrero-Osuna HA, Jaramillo-Martínez R, Torres-Hernández MA, Díaz-Flórez G. Design and Fabrication of a Compact Evaporator–Absorber Unit with Mechanical Enhancement for LiBr–H2O Vertical Falling Film Absorption, Part II: Control-Volume Modeling and Thermodynamic Performance Analysis. Technologies. 2026; 14(1):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14010033

Chicago/Turabian StyleDíaz-Flórez, Genis, Teodoro Ibarra-Pérez, Carlos Alberto Olvera-Olvera, Santiago Villagrana-Barraza, Ma. Auxiliadora Araiza-Esquivel, Hector A. Guerrero-Osuna, Ramón Jaramillo-Martínez, Mayra A. Torres-Hernández, and Germán Díaz-Flórez. 2026. "Design and Fabrication of a Compact Evaporator–Absorber Unit with Mechanical Enhancement for LiBr–H2O Vertical Falling Film Absorption, Part II: Control-Volume Modeling and Thermodynamic Performance Analysis" Technologies 14, no. 1: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14010033

APA StyleDíaz-Flórez, G., Ibarra-Pérez, T., Olvera-Olvera, C. A., Villagrana-Barraza, S., Araiza-Esquivel, M. A., Guerrero-Osuna, H. A., Jaramillo-Martínez, R., Torres-Hernández, M. A., & Díaz-Flórez, G. (2026). Design and Fabrication of a Compact Evaporator–Absorber Unit with Mechanical Enhancement for LiBr–H2O Vertical Falling Film Absorption, Part II: Control-Volume Modeling and Thermodynamic Performance Analysis. Technologies, 14(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14010033