1. Introduction

Research on Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), commonly known as drones, has been increasing in recent decades due to a wide array of civilian and military applications [

1,

2,

3]. Fields such as precision agriculture (PA) and disaster management have a notable impact on the development of this kind of technology as well [

4,

5].

Among the various UAV configurations, two platforms predominate: fixed-wing UAVs, valuable for their endurance and wide-area coverage, and multi-rotor UAVs, known for their agility, hovering, and vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) capabilities [

2,

3,

4].

However, despite advancements in several applications, persistent challenges keep UAVs away from high-performance operations, including battery life, robust autonomous navigation, and security [

6]. According to [

7], an appropriate safety control strategy must function through three stages. First is the prevention phase, where the controller tries to keep the system away from destructive events. Response is the next stage, where the controller is applied to mitigate disturbances, faults, or attacks, ensuring the system controllability. At the end, in the recovery stage, the principal controller purpose is to restore and maintain the desired system performance. Furthermore, UAVs are more vulnerable to faults due to their extensive integration of automation technology [

8], leading to significant research in fault-tolerant control (FTC) to ensure a reduction in the aircraft failure rate and, in several cases, to provide them with the ability to recover and complete the mission, even in the presence of a failure [

9]. Additionally, due to the long list of applications, these vehicles often operate in unpredictable environments, requiring the development of robust controllers, which can face different undesirable situations, such as wing-related scenarios, by using a high-order sliding mode (HOSM) [

10].

Scenarios where UAVs are tasked with carrying liquid payloads, such as agricultural spraying, which are increasing due to the growing economic challenge of satisfying society’s high demand [

11], create significant challenges [

4,

12].

Partially filled containers on drones introduce complex dynamics due to the movement of the liquid inside. Therefore, a phenomenon related to the liquid’s free surface, known as sloshing, appears with even a small UAV’s movements [

13]. The sloshing effect becomes problematic during flight maneuvers, such as obstacle avoidance, external disturbances, or anything else that can produce a change in the drone’s acceleration. The moving liquid produces unpredictable forces that impact vehicle control performance and stability, leading to flight trajectory deviations, undesirable oscillations, and, in extreme cases, collisions [

12,

14].

To analyze the complexity of vehicle–liquid coupled dynamics, equivalent mechanical models, such as the mass–spring–damper model and the pendulum model, have frequently been employed. Remarking on the importance of providing stability through the suppression or mitigation of liquid sloshing is a research objective. Different methods for mitigating sloshing dynamics have been studied. Principally, these can be categorized into passive and active methods. Passive methods refer to those that can reduce sloshing dynamics through the use of a particular shape or anything else inside the tank that can modify the liquid’s dynamic, such as baffles [

12,

15]. Active methods are those that reduce liquid sloshing dynamics by controlling actuators, such as the UAV’s motors [

13,

14].

Even with the advances in anti-sloshing solutions, there remains an active area of research. Various control techniques have been applied to systems subject to sloshing, including Proportional–Integral–Derivative (PID) controllers, Linear–Quadratic Regulator (LQR),

[

13,

16,

17,

18,

19], and some non-linear feedback schemes [

14,

20]. However, many advanced control laws require full knowledge of the system, including the liquid’s slosh rate and angle, which are difficult to measure directly, motivating the development of output–feedback controllers that utilize state estimators [

14,

17]. Linear Quadratic Gaussian (LQG) controllers have been proposed to estimate and control the liquid’s sloshing, measuring the position and attitude of the quadrotor rather than treating the sloshing as a disturbance [

17].

Building upon all these precedents, this paper proposes a nonlinear control strategy. While many studies present robust linear controllers, they often rely on linearized models for their control laws, which may not capture the complete system dynamics. Other advanced procedures, such as state estimation and adaptive robust control, can be applied [

14,

20], but they are computationally demanding and make it complicated to perform a formal stability analysis. Therefore, the main contributions of this work are the following:

A new nonlinear dynamic model is derived employing the Euler–Lagrange formalism based on a quadrotor, represented as planar vertical take off and landing (PVTOL), transporting a liquid payload. Sloshing dynamics are modeled as a pendulum system, adapted from [

21].

A nonlinear control law is generated based on the specific dynamic model previously obtained. The proposed control law is designed to handle the vehicle–liquid coupled dynamics, ensuring robust horizontal trajectory tracking, a critical maneuver in agricultural spraying [

4], while simultaneously maintaining a stable altitude and actively suppressing the liquid slosh oscillations. The stability of the entire closed-loop system is formally proven using Lyapunov’s direct method.

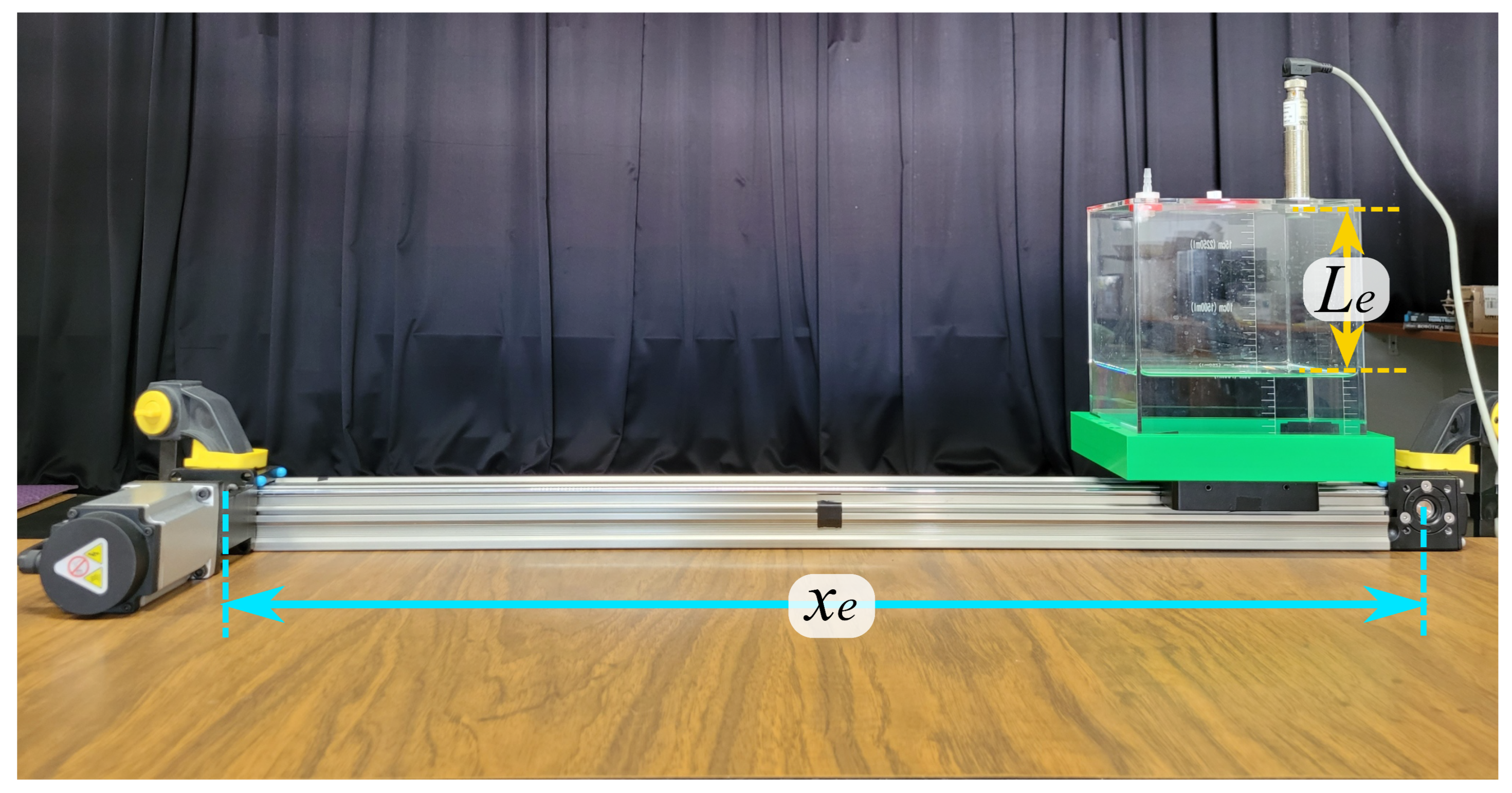

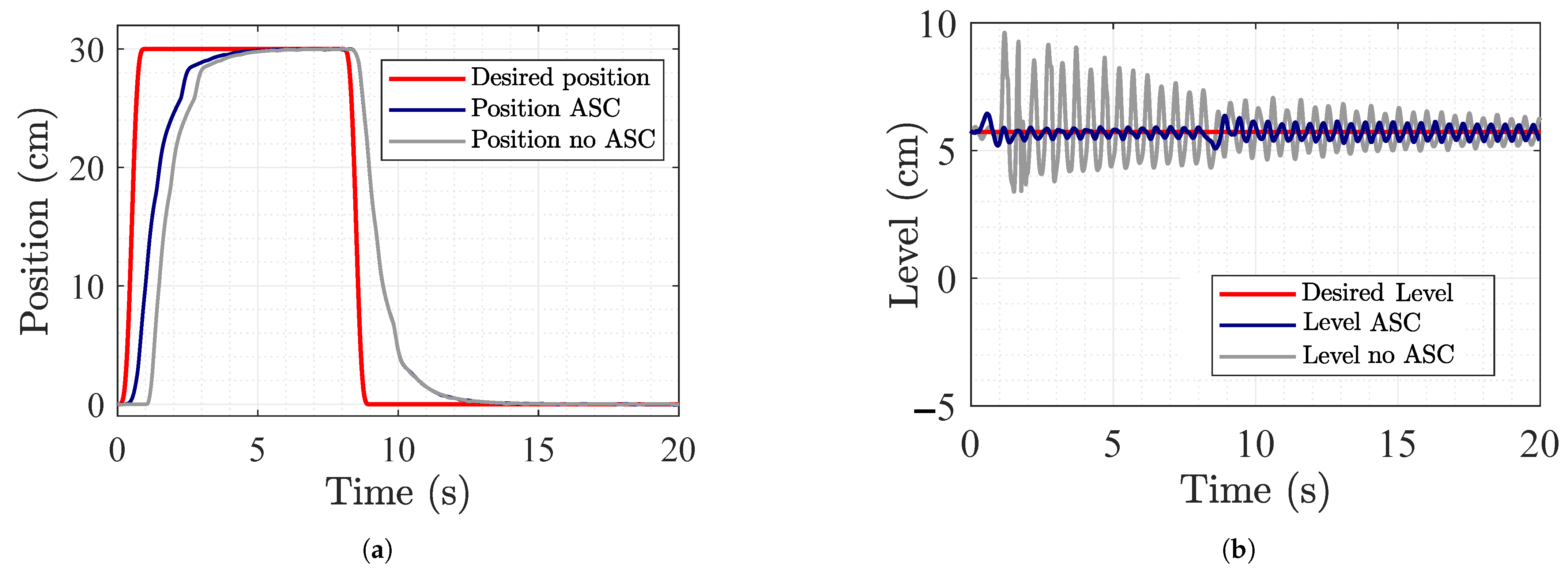

The proposed nonlinear model and control strategy are validated through comprehensive numerical simulations in MATLAB/Simulink R2024a, demonstrating stable altitude regulation and effective sloshing suppression under realistic operating conditions. The controller performance is systematically compared with a classical Proportional–Derivative controller. In addition, the liquid sloshing model adopted in this work is experimentally validated using a dedicated laboratory platform presented in

Appendix A, where pure translational motion along the

x-axis is considered. This experimental evidence supports the physical relevance of the sloshing model employed in the proposed control framework.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the derivation of the dynamic model.

Section 3 details the design of the proposed controller.

Section 4 provides a Lyapunov stability analysis.

Section 5 details how the proposed controller’s performance was validated through numerical simulations in MATLAB/Simulink, its respective comparison against a PD controller, and the expected real implementation of the proposed controller. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper and suggests avenues for future research.

2. Dynamic Model of the PVTOL UAV Carrying a Liquid Payload

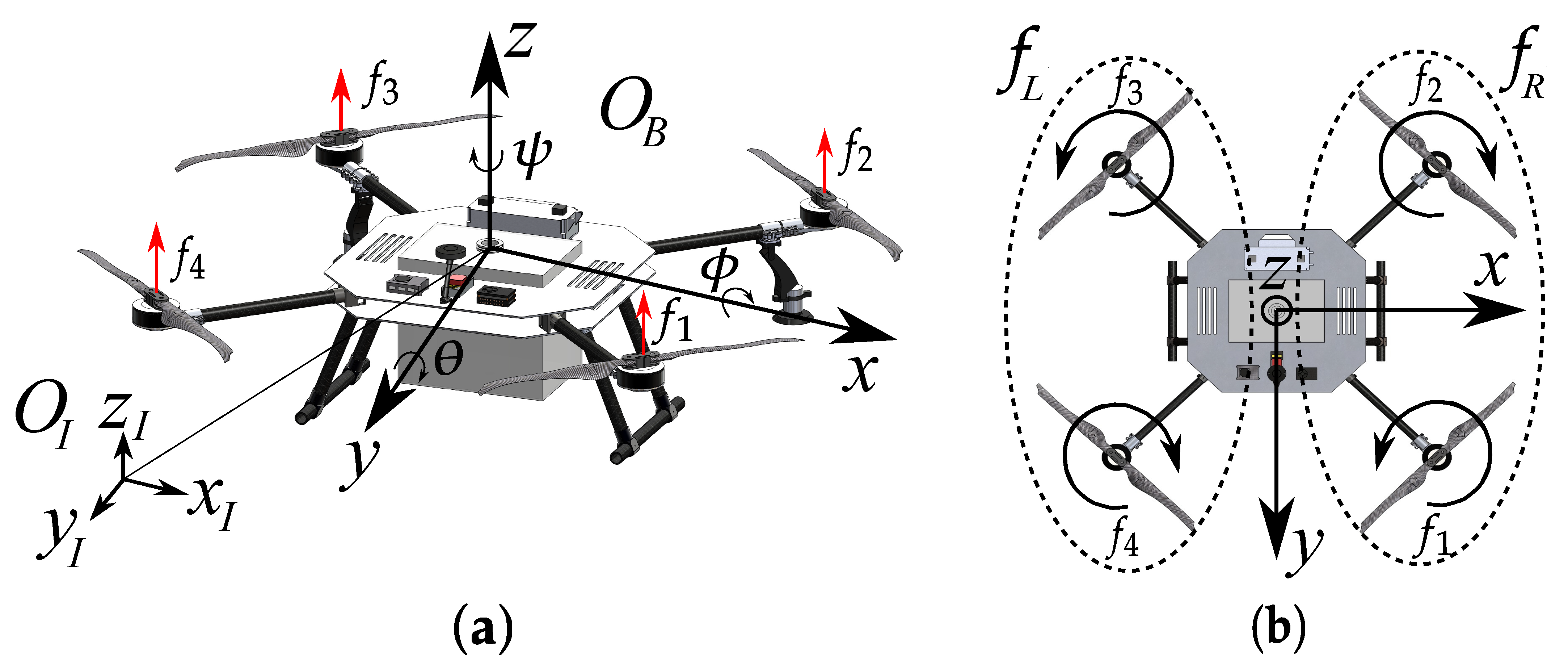

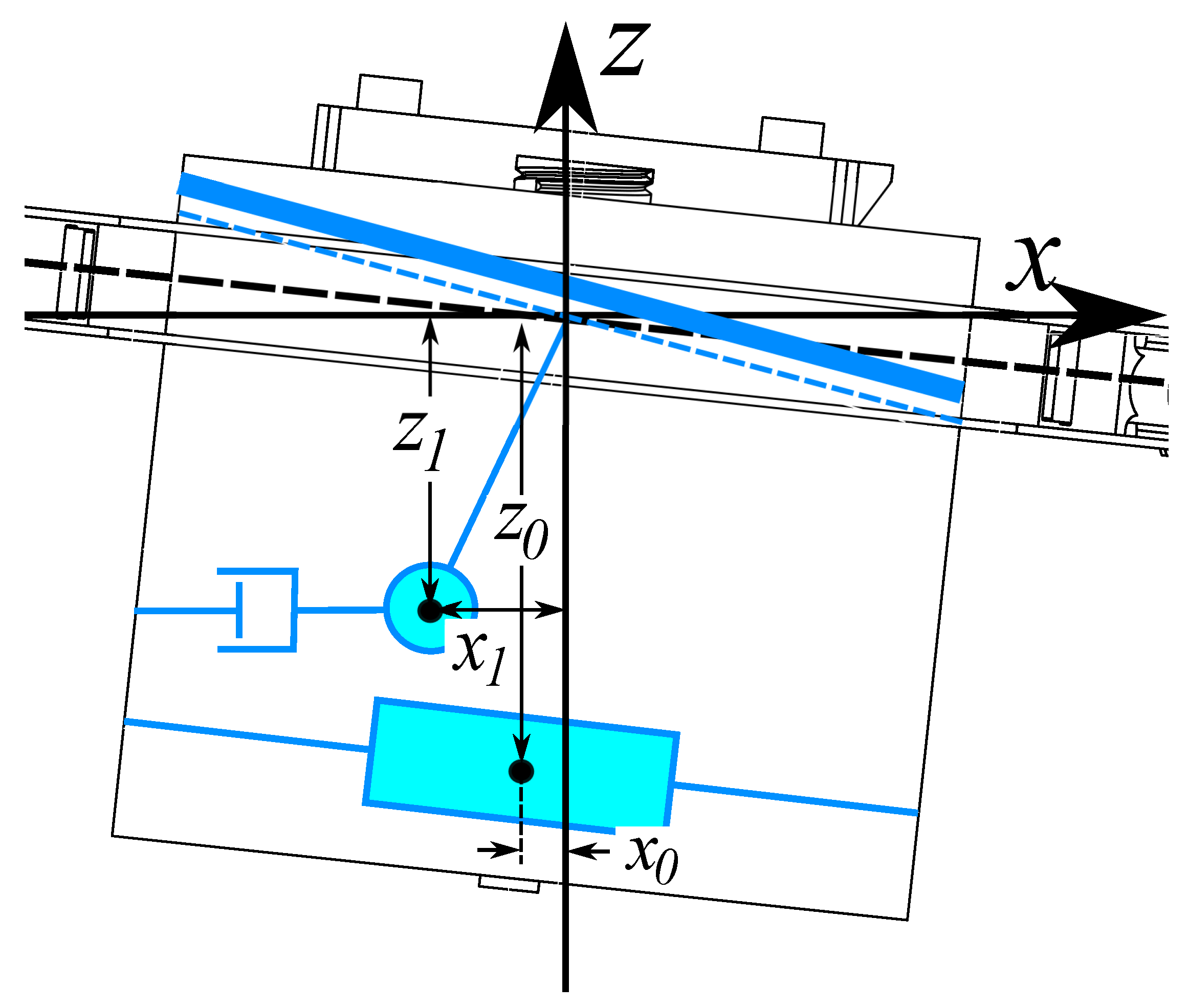

A quadrotor UAV carrying a liquid payload is modeled in this section, by considering that the vehicle is evolving in its longitudinal plane (as a PVTOL vehicle) (see

Figure 1). The following assumptions are stated in order to obtain its dynamic model:

The vehicle structure is rigid and symmetrical.

The center of mass coincides with the body frame .

The propellers are rigid.

The roll moment generates a force perpendicular to the z-axis.

The dynamics along the y-axis, as well as the pitch and yaw dynamics, are assumed to be fully controlled.

The quadrotor aerial vehicle consists of four independently actuated rotors that generate thrust and control torques along the axes of rotation of the propellers. When the vehicle evolves in its longitudinal (or lateral) plane, its dynamics can be approximated by a PVTOL model, shown in

Figure 1b. From this figure, it can be observed that the two left rotors produce the resultant force

, whereas the two right rotors generate

. As illustrated in

Figure 1b, the propellers rotate in opposite directions in a counter-rotating configuration: propellers

and

rotate in the same direction, while propellers

and

rotate in the opposite direction. This arrangement ensures the cancellation of the net yaw torque under symmetric operating conditions. Vertical motion along the

z-axis is achieved by uniformly increasing or decreasing the rotational speeds of all motors. In contrast, differential variations between the left and right rotor speeds generate a net force in the horizontal plane, enabling translational motion along the

x-axis and inducing the associated roll dynamics.

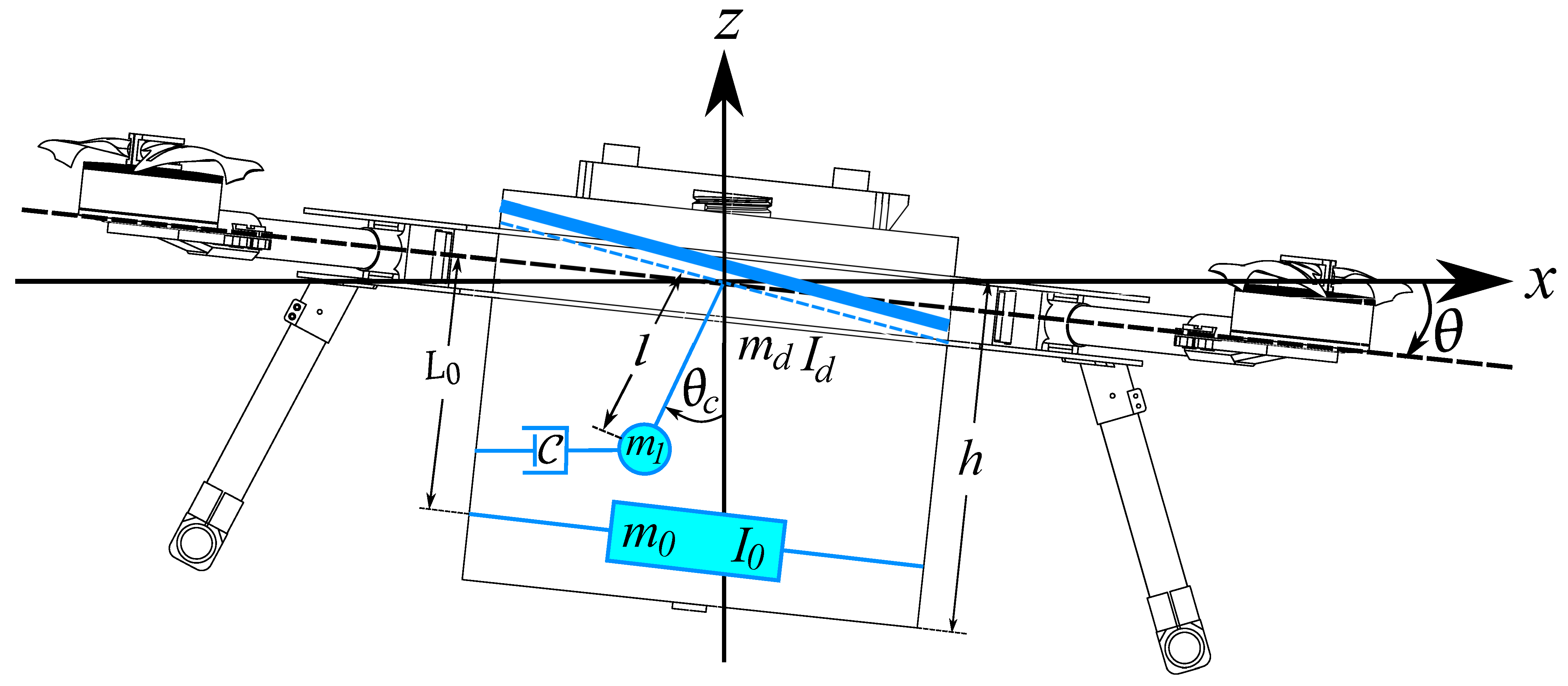

Following the same modeling approach,

Figure 2 shows a container partially filled with liquid mounted on the quadrotor. In this configuration, the VTOL system is modeled as a PVTOL aircraft carrying a liquid payload contained in a rectangular tank. The liquid sloshing dynamics are approximated using an equivalent pendulum model, following the approach reported in [

22]. Also,

Figure 3 provides a detailed view of the PVTOL–payload system, highlighting the geometric parameters, reference frames, and generalized coordinates used for the mathematical modeling. This zoomed representation is introduced to clearly define the relative motion between the vehicle and the liquid payload, which will be employed in the derivation of the coupled dynamical model.

It should be emphasized that the free surface of a liquid inside a partially filled container represents a major problem in many research areas because of the complexity of the solution. The liquid free surface can experience different types of surface motion depending on the container shape and disturbance type, and many variables interact at the same time [

21]. A way to represent the sloshing dynamics inside a container is by using equivalent mechanical models, such as the Mass–Spring–Damper model or the pendulum model [

22]. The latter is the one adopted throughout this work.

The Euler–Lagrange formalism is used to derive the equations of motion for the VTOL system carrying a liquid payload. First, the expressions for the kinetic and potential energy of the overall system must be obtained [

23]. The kinetic and potential energies corresponding to the PVTOL are represented by

and

, respectively, while the container with the equivalent pendulum model for liquid sloshing is defined by

and

, respectively. In this way, both sets of energies can be defined separately [

24].

Then, the following expressions can be established:

where all the variables of the system are described in

Table 1. The positions and velocities of the masses

and

, respectively, are defined relative to the center of mass of the PVTOL, as follows:

Defining

and

as the total kinetic and potential energies of the system, respectively, leads to the Lagrangian

, as follows:

Once the Lagrangian is established, Euler–Lagrange equation is applied with energy dissipation, as follows:

where the generalized coordinates, the generalized forces, and the Rayleigh dissipation function are given by

,

, and

, respectively. Then, applying (

6), the non-linear model of the system is obtained:

where

and

.

The resulting set of equations can be represented in a more comprehensible and manageable matrix form:

with:

where

and

denote the total mass and inertia of the system, respectively.

3. Proposed Controller Design

In this section, the proposed controller design for the VTOL system carrying a liquid payload is presented.

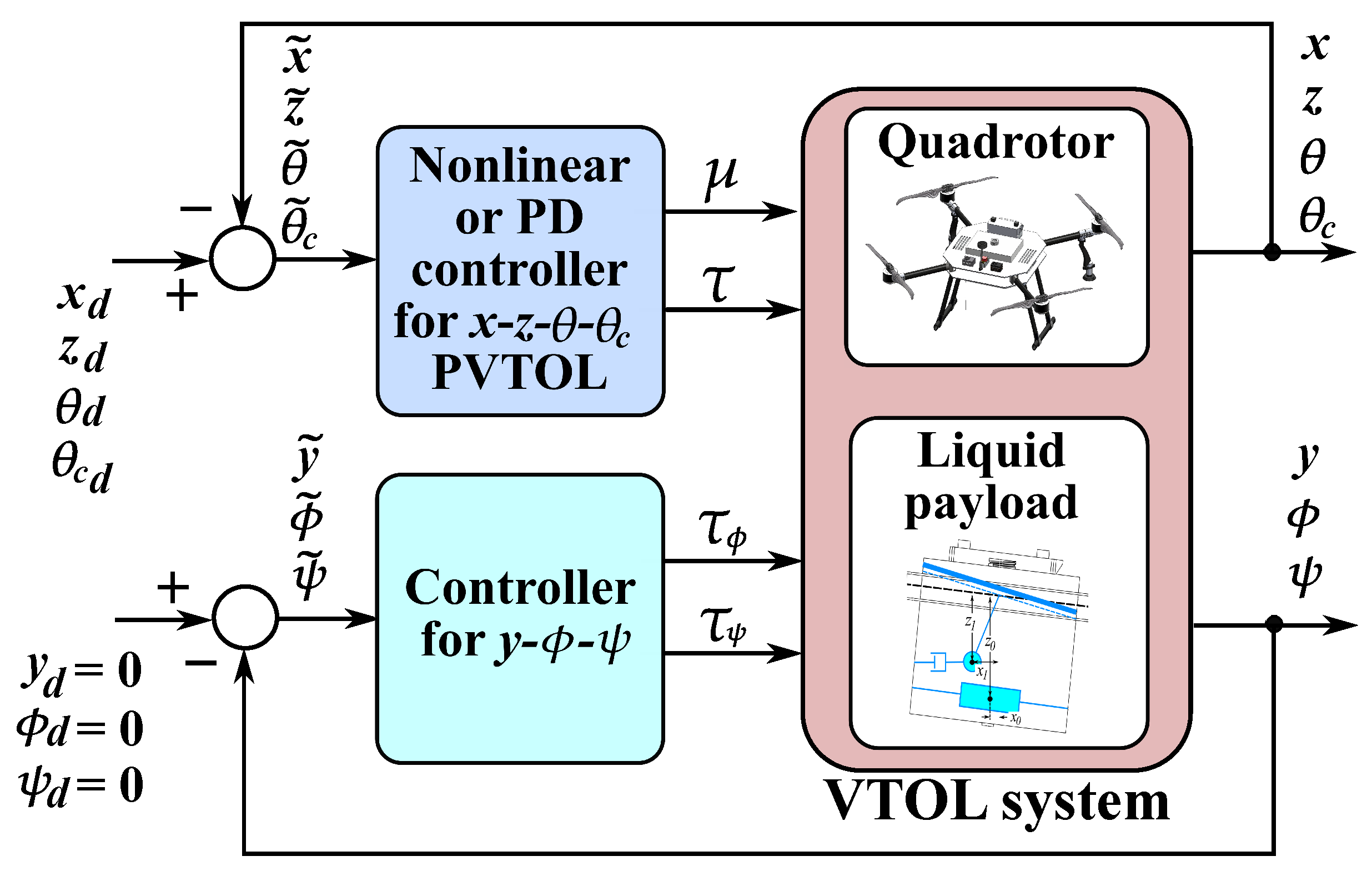

Figure 4 illustrates the overall control architecture of the system, which is structured in a hierarchical manner and consists of two main control loops.

The upper control loop is responsible for the longitudinal PVTOL dynamics, regulating the translational motion along the x- and z-axes, as well as the roll angle and the container inclination . The proposed nonlinear controller or PD-based controller are employed to track the desired reference signals , generating the control inputs and , which are applied to the quadrotor subsystem. The lower control loop governs the remaining degrees of freedom associated with the lateral and rotational dynamics, namely the y-position and the pitch and yaw angles . Since the focus of this work is restricted to planar motion, the corresponding reference signals are set to zero, i.e., . This controller generates the torques and to stabilize the system around the desired equilibrium.

To facilitate analysis and control design for, the system presented in (

7)–(10) can be expressed in a decoupled representation, allowing a clear separation of the PVTOL dynamics from those related to liquid sloshing, represented by

, and

. Thus, the following equations are stated:

The non-linear system (

15)–(18) can be represented in a reduced altitude dynamics by considering a thrust control input

, as follows:

Therefore, (

15)–(18) can be rewritten as

We assume that the altitude

z eventually attains the desired setpoint

, i.e., the position error

converges to zero (

). Then, system (

20) is reduced to the following:

In order to control the complete displacement of the PVTOL system, the desired horizontal displacement dynamics is defined as

where

is a constant that defines the convergence rate, and

is the error between the actual position

x and the desired position

. If the desired position

is a constant, the second derivative of

is

. Then, introducing it in the first derivative of (

22) yields

where

represents the combined sloshing terms affecting the horizontal displacement.

Given that the horizontal displacement of the PVTOL depends on the inclination angle, the virtual desired angle

and the corresponding error

can be used as follows:

By solving (25) for

and substituting it into (

23), the following expression is obtained:

Expanding (

26), the following is obtained:

And solving (

22) for

,

Both equations, (

27) and (

28), lead to the following state-space representation for the translational dynamics:

The control strategy for the PVTOL’s roll dynamics tracks a desired reference

, requires defining the error between the desired roll angle

and the measured roll angle

, depicted as follows:

The resulting dynamics of the roll angle error are determined by substituting the expression for the PVTOL’s roll acceleration, as defined in (

21), into the second derivative of (

30), yielding the following resulting equation:

The control input

is designed to ensure that the error dynamics converge to zero while rejecting the sloshing disturbance

, as follows:

Then, substituting the input (

32) into (

31) yields

which can be rewritten in state-space form as follows:

Given the subsystems described in (

29) and (

34), the objective is to analyze their asymptotic stability using Lyapunov theory. By constructing appropriate Lyapunov candidate functions for each subsystem, it is possible to demonstrate that the corresponding error states converge to their respective references, ensuring the stability of both the translational and roll-angle error dynamics. This analysis guarantees that the closed-loop system remains stable under the proposed control laws and that the tracking errors decay asymptotically. In this context, the goal is to determine suitable values for the controller gains such that the resulting state matrices become Hurwitz matrices, ensuring asymptotic convergence through the Lyapunov framework.

5. Simulation Results

To validate the dynamic model derived in

Section 2 and the performance of the proposed anti-sloshing control strategy from

Section 3, the proposed control is first evaluated; subsequently, a comparative analysis is conducted against a standard Proportional Derivative controller with active sloshing suppression.

The physical relevance of the sloshing model is further supported by the experimental results presented in

Appendix A. The same model is implemented on a laboratory platform under pure translational motion, showing sloshing behavior consistent with the simulation results reported in this section.

The desired trajectories used in the simulations are defined following typical flight patterns employed in precision agriculture applications. As illustrated in [

26], agricultural missions usually consist of two main stages: first, the UAV performs a vertical take-off to reach a prescribed operating altitude. Once this altitude is achieved, horizontal translational motion is executed to follow the desired path over the field.

In practical agricultural scenarios, such horizontal motion is commonly carried out sequentially along the x and y directions, or vice versa, depending on the mission requirements. In this work, after reaching the desired altitude, the UAV is commanded to translate along the x-axis only. This choice is consistent with the PVTOL formulation adopted and is sufficient to capture the essential dynamics relevant to agricultural spraying or monitoring tasks. It is worth noting that reproducing full agricultural coverage patterns would require controlling the yaw angle to reorient the vehicle between straight-line passes.

The numerical simulations were carried out in MATLAB/Simulink. The common physical parameters for the system used in both scenarios are detailed in

Table 2, where

refers to the water density,

is the distance between the PVTOL’s center of mass and the motor, and the other parameter has already been described in

Table 1. The simulation was configured using a fixed-step numerical integration scheme. The total simulation time was set to 120 s, employing an ode3 fixed-step solver with a step size of

. These settings were selected to ensure numerical stability and accurate capture of the system dynamics.

5.1. Simulation of the Proposed Nonlinear Controller

The controller gains of the proposed nonlinear controller were tuned to minimize overshoot while ensuring fast convergence and closed-loop stability. The selected gains are summarized in

Table 3 and were adjusted based on the system dynamics and control objectives. Specifically, gains

and

are associated with the altitude dynamics,

and

regulate the horizontal translational dynamics, and

and

are related to the rotational dynamics. In addition, the feasibility and correctness of the gain selection were verified through YALMIP toolbox [

27]. This procedure ensured that the resulting gain matrices satisfied the required stability and performance conditions of the proposed control framework.

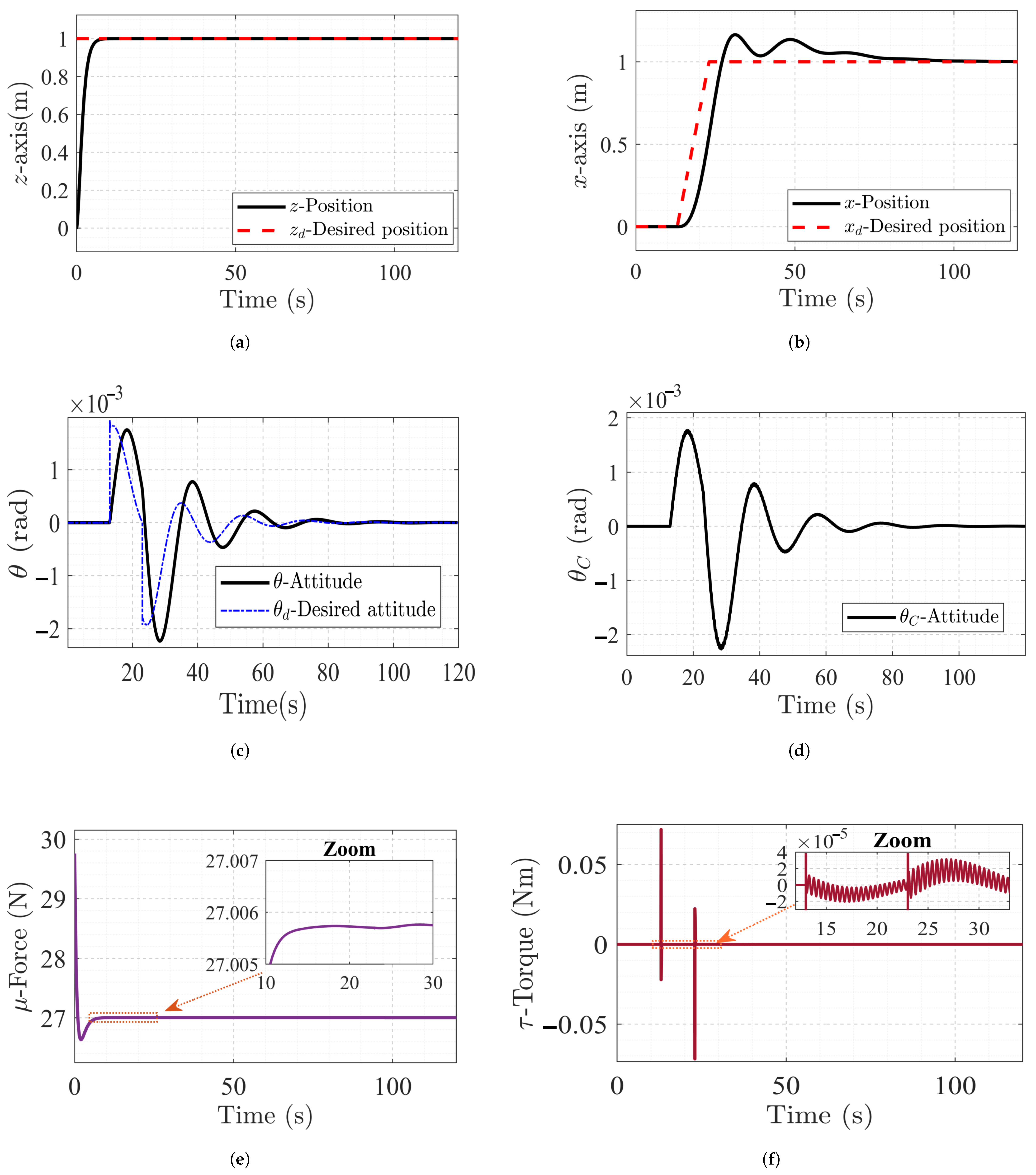

The test scenario was designed to prove the control ability to deal with vertical and horizontal displacements, as shown in

Figure 5, where the horizontal maneuver is known as the one able to excite the liquid dynamics. First, the PVTOL performs a take-off to an altitude of

, reaching the desired altitude at

, without overshoot, as shown in

Figure 5a.

Once the altitude is almost stabilized, at

, a ramp reference is given to move the UAV to a horizontal desired position,

, which is reached at

with minimal overshoot, as shown in

Figure 5b, demonstrating the controller’s tracking capability.

Figure 5 illustrates the system’s rotational dynamics too and, consequently, the control sloshing suppression effectiveness. The attitude tracking shown in

Figure 5c demonstrates how the actual roll angle

closely follows the generated desired angle

to achieve the desired horizontal position without losing altitude. The principal controller’s objective is demonstrated in

Figure 5d, which plots the sloshing angle

, where it is shown how the horizontal displacement excites the sloshing dynamics and how the active control suppression works to keep

near zero.

It is important to note that most control strategies reported in the literature experience altitude degradation while tracking the desired horizontal position. In contrast, the proposed controller achieves accurate horizontal trajectory tracking while effectively suppressing liquid sloshing, without compromising altitude regulation. Moreover, this performance is obtained using a simplified gain structure, which represents a critical requirement for many practical multirotor applications.

The control inputs are shown in

Figure 5. The total thrust force

, after a maximum thrust force of

applied during take-off, stabilizes at approximately

at

, which corresponds to the force needed to counteract the total weight of the system, as shown in

Figure 5e. The torque control signal peaks shown in

Figure 5f are there as a result of the control law to stabilize the UAV under horizontal maneuvers and sloshing dynamics as well.

5.2. Comparison with Conventional PD Controller

To appraise the relative performance of the proposed controller, a Proportional–Derivative (PD) controller was simulated as a baseline. The PD gains shown in

Table 4 were tuned to ensure system stabilization, assigning their respective proportional and derivative gains (

and

, respectively) to each system output, under the same simulation conditions.

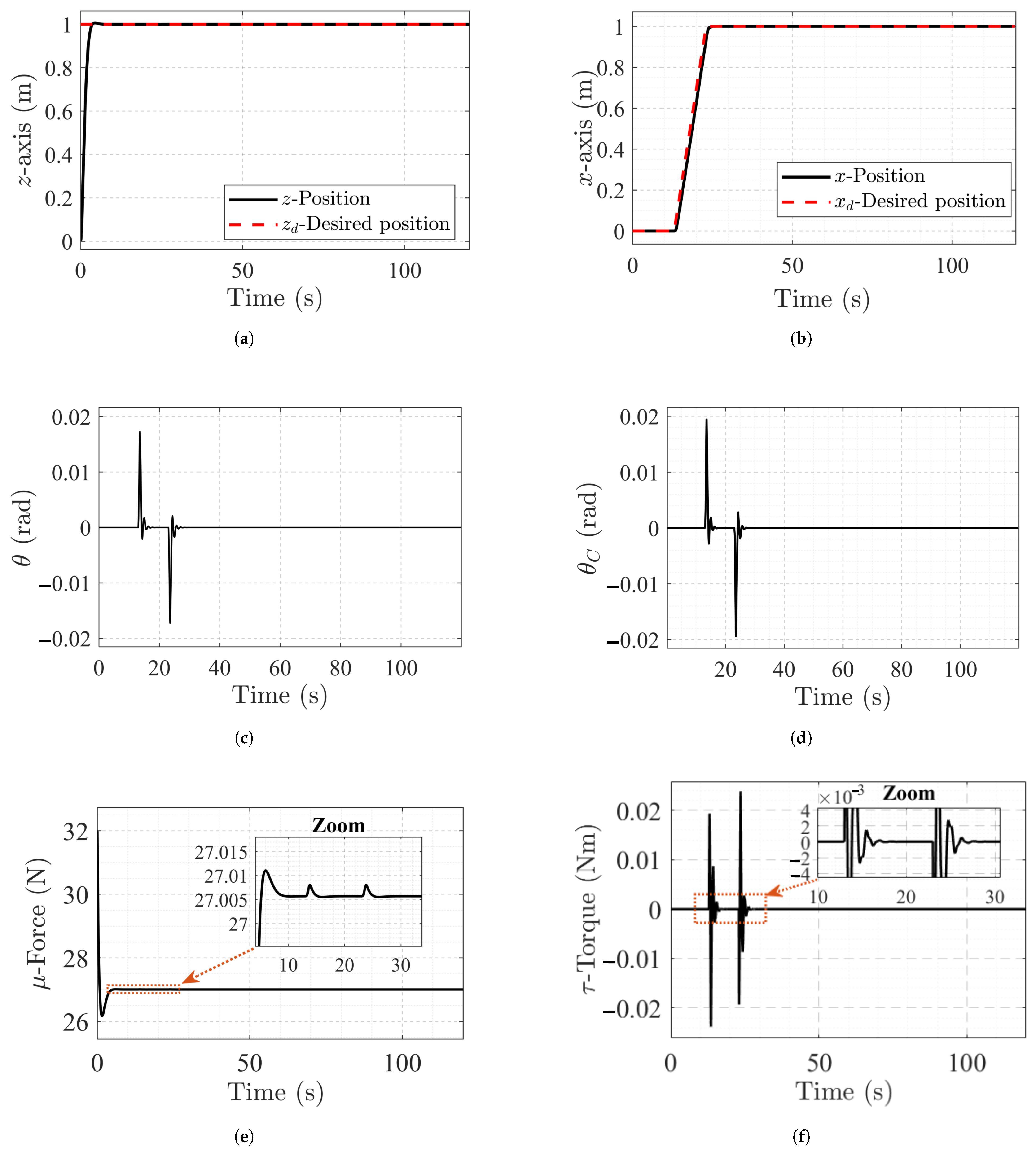

Figure 6a shows that the PVTOL takes off at a desired altitude of

, with a settling time of less than

and minimal overshooting, following the same pattern as that of the control system in the previous simulation. Once the desired altitude is reached, a ramp reference signal is introduced to move the UAV to a desired horizontal position,

, achieving a settling time of less than

, without significant overshoot, and excellent tracking of the reference signal. Therefore,

Figure 6b shows proper suppression of the liquid sloshing.

Due to the manipulation of the PVTOL torque, in

Figure 6c, it can be observed that the roll angle dynamics of the UAV tend towards zero in less than

, demonstrating excellent rotational stabilization of the vehicle, indicating that it reaches the desired horizontal position while actively suppressing the sloshing of the liquid inside the tank.

Figure 6c shows how the angle

, which represents the sloshing, temporarily coincides with the respective horizontal movements of the UAV, accompanied by a notable decrease in the oscillatory behavior of

, which is critical to demonstrate the effectiveness of the controller in suppressing the liquid sloshing dynamics.

Figure 6e illustrates the response of the control signal for the total thrust force generated by the motor–propeller combination,

. This response reaches a maximum of

and then stabilizes at approximately

after the time

, demonstrating that the force necessary to counteract the total weight of the system while hovering is generated in a correct and stable manner. The peaks evident in the zoom of

Figure 6e indicate sustained losses during position change maneuvers, a detail that is not practically present in the zoom shown in

Figure 5e. Finally, the applied torque control signal shown in

Figure 6f demonstrates the behavior of the control signal when faced with the task of stabilizing the rotational dynamics of the PVTOL while actively suppressing liquid sloshing dynamics. This suppression causes the control signal

to tend toward zero with minor peaks than those shown in

Figure 5f.

5.3. Agricultural Hexarotor System Implementation

As future work, the nonlinear control for a liquid payload will be implemented in a 40 kg agricultural drone (see

Figure 7) with the mechanical specifications described in

Table 5. This large-sized UAV features a simplified hexagonal skeleton for rapid implementation and a flat-profile liquid tank that facilitates sloshing in both backwards and forward displacement. The relevant parameter values for flight dynamics are presented in

Table 6. These values correspond to drone behavior in autonomous mode for assigned trajectories in the Mission Planner software and together regulate the leaning angle, translational accelerations, and time response to control actions.

This system will enable the effective evaluation of anti-sloshing control algorithms in agricultural applications, contributing to the advancement of efficient spraying activities.

At present, this work is limited to numerical validation, while the experimental stage is left for future research. The hexarotor platform shown in

Figure 7 has already been developed in the laboratory, as reported in [

11]. Therefore, the proposed controller will be implemented once the corresponding safety validation tests of the platform have been completed.