1. Introduction

One of the most significant and critical engineering infrastructures is the power transmission system. As a vital component of modern electrical systems, power transmission systems transport electricity from generation sources to distribution networks and end users. In addition, they play a key role in enabling reliable and transparent electricity markets by ensuring secure power delivery between market participants.

In the context of ongoing transformations in modern power systems, the role of transmission system facilities is evolving beyond their traditional functions. This transition raises significant concerns regarding the potential deterioration of transmission system reliability, particularly under increasing operational complexity.

Power transmission systems are currently undergoing major changes, largely driven by the following factors:

the large-scale integration of renewable energy sources, which requires enhanced system flexibility to balance generation and demand;

the global commitment to reducing CO2 emissions in order to mitigate climate change;

the continuous increase in electricity demand due to economic development, population growth, and technological advancement;

the aging of transmission infrastructure, which leads to higher maintenance costs, increased outage rates, and reduced operational efficiency;

the need for appropriate investments in transmission capacity expansion and generation facilities.

The European Union has set a target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030 compared to 1999 levels, with the objective of achieving climate neutrality by 2050 [

1]. Consequently, adequate investments in transmission and generation capacity are essential to support a successful transition toward a carbon-neutral energy system [

2,

3,

4].

Maintaining an uninterrupted supply of electricity is widely regarded as an indicator of national development and economic prosperity. As a result, decision-makers prioritize the provision of reliable and secure electrical power for consumers.

The reliability and security of power systems are reflected in the strength and stability of the electricity grid. Grid security is associated with robustness and the ability to respond rapidly to disturbances while maintaining stable operation under uncertain conditions. Transmission system reliability, on the other hand, refers to the capability of high-voltage networks to continuously supply electricity and meet customer demand under normal operating conditions.

Despite significant advancements in grid design, configuration, and operation, power system failures remain inevitable. Security and reliability assessments have always been crucial to ensuring the dependable and cost-effective operation of power systems. Power grid failures may result in serious economic and social consequences. Cascading failures typically originate from the malfunction of one or more system components and subsequently propagate throughout the network. The well-established N−1 criterion remains a fundamental indicator for evaluating transmission system security and reliability, as it ensures continued system operation following the unplanned outage of a critical component, such as a generator, transmission line, or power transformer.

Ensuring transmission system security and uninterrupted electricity supply is essential for public safety and business continuity. However, various external factors—including adverse weather conditions and natural disasters such as earthquakes, windstorms, and wildfires—pose persistent threats to grid operation. Enhancing the robustness of fragility models represents an important step toward improving the understanding of power grid vulnerabilities. Furthermore, the intermittent and stochastic nature of wind and solar generation introduces additional challenges related to voltage regulation, frequency control, and overall grid stability.

When one or more power system components fail, the system as a whole may experience cascading failures. A cascading outage is defined as a sequence of disconnections triggered by an initial disturbance. Such events may result from human actions or deliberate attacks, natural phenomena such as strong winds, flooding, or lightning strikes, or load–generation imbalances [

5]. If an outage affects a significant portion or the entirety of the transmission system, it is usually referred to as a blackout, which can be difficult to mitigate through manual intervention.

Table 1 summarizes incidents recorded in Continental Europe between 2020 and 2023 according to dominant technical criteria and severity levels. Only significant events are reported and classified using a severity-based scale: Scale 0 for significant local events; Scale 1 for major events involving operational security limit violations; Scale 2 for large-scale events with the potential for wide-area impacts; and Scale 3 for severe events occurring within a single control area.

Figure 1 shows the number of incidents recorded between 2020 and 2023 categorized by incident type.

Statistical analyses of power grids with respect to cascading failure behavior provide valuable insights into the strengths and weaknesses of different grid configurations [

6]. In complex systems such as power grids, increasing the system size—defined by the number of components—may lead to more abrupt and severe failure dynamics, even when modeled using both realistic and synthetic network representations [

7]. The rapid growth in medium- and small-scale renewable energy installations can further reduce grid reliability if not properly managed [

8]. The stability of power systems plays a central role in the energy transition, influencing its feasibility, challenges, and long-term prospects [

9]. To mitigate the variability of renewable energy sources, maintain grid stability, and enable temporal energy shifting, energy storage systems are increasingly recognized as essential components of modern power systems [

10].

A wide range of engineering software tools is commonly used for power flow and reliability studies. These tools allow engineers to model, simulate, and analyze power transmission systems in order to assess steady-state conditions, identify potential weaknesses, and plan for future expansion and operational stability. However, the growing complexity of modern grids necessitates enhancements beyond conventional engineering analyses.

One of the primary motivations for applying complex network (CN) theory to power grids is its ability to model the grid’s robustness and vulnerability to cascading failures. By representing the transmission system as a network—where nodes correspond to substations, generators, and loads, and edges represent transmission lines—complex network analysis provides a complementary perspective on system structure. Traditional reliability assessments of integrated energy systems based on CN theory often focus on static topological properties and rarely incorporate operational characteristics and physical constraints. However, accuracy and computational efficiency are critical requirements for evaluating practical reliability [

11]. Since different network components exhibit varying degrees of importance, identifying critical elements is essential for improving resilience and reliability [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

Maintaining reliability and security in modern power systems has become increasingly challenging as these systems incorporate a growing number of innovative, networked components, such as smart devices, electric vehicles, renewable energy sources, heat pumps, and battery storage systems. Rapid variations in demand and generation introduce further operational difficulties. Given the intermittent nature of renewable energy sources, continuous security assessments are required to ensure reliable transmission system operation and to enhance model accuracy.

Although extensive research has been conducted in this area, further investigation remains necessary due to the increasing complexity introduced by modern power system technologies. The primary motivation of this study is to address these challenges by evaluating the reliability and security of a power transmission system through a combined approach that integrates the Neplan engineering software with complex network analysis using Python NetworkX. This hybrid methodology leverages the strengths of both conventional power system modeling and advanced network theory.

By integrating complex network models with traditional engineering tools, the proposed approach provides a more comprehensive framework for managing and improving grid performance, security, and reliability. Complex network analysis enhances conventional methods by offering a system-wide perspective on network topology and behavior. The main advantages of this combined approach include the following:

Enhanced reliability and security, achieved through the identification of structurally critical components using centrality measures and their validation through power flow analysis;

Improved system control and operation, supported by a deeper understanding of network behavior under different operating conditions;

Optimized planning, enabling more effective transmission infrastructure development to accommodate growing demand and increased renewable energy penetration.

The results obtained in this study demonstrate that combining power system functional modeling with complex network structural analysis provides a dual perspective that links grid topology with operational performance, thereby improving reliability and security assessments and supporting the development of more realistic transmission system models.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides an overview of transmission system reliability and robustness and introduces the fundamentals of complex network analysis.

Section 3 describes the dataset and the proposed methodology.

Section 4 presents and discusses the obtained results. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future research.

2. Reliability and Robustness of the Power Transmission System and Analyses of Complex Networks

A stable and reliable supply of electricity fundamentally depends on the security and reliability of transmission system facilities. Reliability ensures that sufficient capacity is available to meet customer demand, whereas security refers to the ability of the grid to withstand disturbances and continue operating in a stable manner under abnormal conditions.

Power transmission systems, which consist of generators, transmission lines, substations, and loads, can be effectively represented as networks, where nodes correspond to system components and edges represent physical connections. Complex network analysis enables a systematic investigation of grid structure and functionality, facilitating the identification of vulnerabilities, fault propagation mechanisms, and strategies for improving system resilience and reliability.

2.1. Power Transmission System Reliability

Power transmission system components, such as transmission lines, power transformers, and circuit breakers, are subject to failures that may occur randomly or as a result of intentional actions. These failures can be caused by extreme weather conditions, equipment malfunction, electrical faults, or mechanical degradation. Various interrelated concepts have been proposed in the literature to characterize the impact of failures or attacks on power grids, including reliability, robustness, resilience, fragility, and vulnerability [

20].

Transmission system reliability is generally described through three key components: operational reliability, resilience, and resource adequacy, as illustrated in

Figure 2. Resource adequacy ensures that sufficient generation capacity is available to meet demand. Operational reliability focuses on the grid’s ability to withstand component outages and prevent cascading failures. Resilience, which has gained increasing attention in recent years, describes the grid’s capability to endure extreme events and recover rapidly following major disruptions.

Several metrics can be used to quantify performance. If a power grid’s normal efficiency is determined by

and its post-damage efficiency by

, then the efficiency-based vulnerability (V

E) can be measured as follows [

21]:

A power system is considered reliable and secure when it can continue operating under both normal and unforeseen conditions. If appropriate preventive or corrective measures are not implemented, cascading failures may occur, potentially leading to widespread blackouts.

Several widely adopted indicators are used to assess transmission system reliability [

22]:

Average Interruption Time (AIT): an indicator measuring the duration of supply interruptions, calculated as the annual total number of minutes during which electricity supply is interrupted;

Energy Not Served (ENS): the estimated amount of energy that customers would have received in the absence of outages or transmission constraints;

Energy Not Delivered (END): the estimated amount of energy that would have been delivered to the point of supply in the absence of disruptions or transmission limitations.

The failure rate of power transformers can be expressed as a ratio of the number of transformer failures occurring within a given year to the total number of transformers in operation during that year, as reported in [

23]:

The relationship between the failure rate of overhead lines

(x) and the overall condition index x can be represented as follows [

24]:

where A, B, and C are the three constants to be determined; the three constants A, B, and C can be estimated using historical statistics of failure rates and monitoring data that have been recorded in a singular time period.

Power flow and contingency analyses represent fundamental tools for power system analysis and are typically performed using specialized engineering software. These analyses determine steady-state operating conditions, including voltage magnitudes, currents, and power flows, under various operating scenarios. Power flow calculations are generally based on iterative numerical techniques, such as the Newton–Raphson or Gauss–Seidel methods. In this study, power flow and N−1 contingency analyses for the system under study were conducted using the Neplan software (Neplan v10) [

25].

2.2. Complex Network Analysis

In complex network theory, a complex system is abstracted as a set of nodes and edges that represent the interconnections between system components. This approach provides a topological framework for characterizing the structural properties of interconnected systems.

The foundations of network science originate from graph theory, which was first introduced by Leonhard Euler in 1736 through his analysis of the Seven Bridges of Königsberg problem [

26]. Later developments include the small-world network concept proposed by Watts and Strogatz in 1998, which demonstrated that many real-world networks exhibit short average path lengths combined with high clustering coefficients. Networks that display these characteristics are said to possess the small-world property [

27].

Complex networks are typically composed of nodes and edges. Nodes represent individual entities within the system, while edges represent the relationships or connections between them. Mathematically, a network can be represented as a graph:

where G is a complex network, and N and E represent the set of nodes and edges, respectively. The node and edge can be referred to as a vertex (V) and as a link (L), respectively. A simple graph can be built as shown in

Figure 3.

From an operational and physical perspective, the sets that make up the graph are of particular relevance when considering the power grid. A graph G (V,E) that has each node vi ∈ V representing a substation, a transformer, lines, or a load of a real power grid is called a power grid graph. If the elements represented by vi and vj are physically connected by a line, then there is an edge ei,j = (vi, vj) ∈ E between two nodes.

Now let us introduce the fundamental mathematical concepts of a network graph, which will help us better understand this study’s structure and motivate its purpose. The concepts that will be applied in this research are as follows [

28,

29]:

Network (graph): A network, also called a graph in the mathematical literature, is a collection of vertices joined by edges. Vertices and edges are also called nodes and links in computer science.

Nodes (vertices) and links (edges): A graph’s basic units or points are called nodes or vertices. In the structure being modeled, each vertex denotes an object or a place. The connections that exist between pairs of vertices are known as links or edges. Every edge connects two vertices, signifying a connection or route between them.

Adjacency: Node A is a node adjacent to node B if and only if there is an edge between nodes A and B. The adjacency matrix A of a simple graph is a matrix with elements Aij.

Path: A path is a set of edges that joins a set of different vertices. No vertices are repeated in this edge sequence, with the exception of closed paths, when only the beginning and end vertices may be duplicated; a path between two nodes A and B in a network is a sequence of nodes A, X1, X2,..., Xn, B and a sequence of edges (A, X1), (X1, X2),..., (Xn, B), where each node and edge in sequence is adjacent to the previous. The length of a path is the number of edges in the path.

Degree of a node: A node’s degree in a network is determined by how many edges it is connected to. The degree ki of a node i in a network with N nodes and M edges is determined as follows:

where A is the adjacency matrix of the network.

Directed and undirected graph: A directed graph is a graph in which the direction of the edge is defined to a particular node; a graph in which the direction of the edge is not defined is called an undirected graph.

Geodesic and eccentricity: The shortest path that connects two nodes A and B is a geodesic between the two nodes A and B in a network, so a geodesic is the path with the minimum number of edges that traverse between nodes. The eccentricity of a node A in the network is the maximum distance between node A and any other node in that network, so it is the maximum length of the shortest path between node A and any other node.

Once the network structure is known, the corresponding topological measures can be calculated. We present these measures as follows:

Degree centrality: Centrality addresses the concept of the importance of central vertices in the network. Degree centrality is a measure of the number of connected edges; the degree centrality of a node i can be calculated as follows:

Eigenvector centrality: Eigenvector centrality is an extension of degree centrality. Eigenvalue centrality is a measure of the importance of a node in a network based on the importance of its neighbors; the eigenvector centrality of a node i can be calculated as follows:

where A is the adjacency matrix and v is the eigenvector correspondent to the largest eigenvalue

.

Closeness centrality: Closeness centrality measures the mean distance from a vertex to other vertices. Supposing d

ij is the length of (the number of edges along) a geodesic path from i to j, then the mean geodesic distance from i to j, averaged over all vertices j in the network, is determined as follows:

Betweenness centrality: This concept measures the extent to which a vertex lies on a path between other vertices. Letting

be 1 if vertex i lies on the geodesic path from s to t, and 0 if it does not, then the betweenness centrality x

i is given as follows:

Formally, if we let

be the number of geodesic paths from s to t that pass through i, and g

st be the total number of geodesic paths from s to t, then the betweenness centrality of vertex i is defined as follows:

Network robustness is commonly assessed through graph connectivity, defined as the minimum number of vertices or edges whose removal would result in network disconnection. Networks with higher connectivity generally exhibit greater robustness, as a larger number of component failures is required to disrupt the overall connectivity.

Power transmission systems can be modeled and visualized as graphs using the Python programming language and the NetworkX library. NetworkX provides a comprehensive set of tools for creating, manipulating, and analyzing complex networks. In the context of power grid analysis, NetworkX enables the following [

30]:

the creation and modeling of complex network representations;

visualizations of network topology and component interconnections;

the calculation of topological metrics, including shortest paths, connectivity, and centrality measures.

By applying NetworkX algorithms, the key elements, potential failure points, and structurally critical components of power transmission systems can be systematically identified.

3. Data Used, System Under Study, and Methodological Approach

3.1. Data Sources

Data related to electrical substations, transmission lines, and power transformers were collected for the western part of the Kosovo Transmission System Operator (KOSTT) network [

31]. In addition, historical failure data were gathered for overhead transmission lines, power transformers, bus bars, and bus bar couplers, together with meteorological data such as ambient temperature values.

The data collection period for the present case study covers four consecutive years, from 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2023. The collected dataset provides a comprehensive overview of the operational behavior and failure patterns of the transmission system under study.

Failures affecting overhead transmission lines include electrical arcing, corona discharge, conductor sagging, conductor breakage, and insulator failures. Electrical faults in power transformers include insulation breakdown leading to short circuits or ground faults, overload conditions, and protection device malfunctions. Bus bar faults may result from insulator failures, flashovers, foreign objects, mechanical damage, or human error. Similarly, bus bar coupler failures can arise from equipment malfunction, operational errors, or external influences.

3.2. Analysis of Retrieved Data

Power transmission system components, such as transmission lines, power transformers, and circuit breakers, may experience various types of failures over time.

Table 2 presents the number of recorded failures affecting network elements of the system under study during the period of 2020 to 2023.

As shown in

Table 2, the highest number of failures related to overhead transmission lines occurred in 2022, with a total of 59 recorded events. Power transformer failures were most frequent in 2020, with 24 recorded incidents. No failures were reported for bus bars during the investigated period, while bus bar coupler failures occurred only in 2021 and 2022. The zero values indicate years in which no failures were recorded for the corresponding components.

Figure 4 shows the annual distribution of failures affecting these transmission system components from 2020 to 2023. For overhead transmission lines, protection relays corresponding to distance protection zones 1 and 2 were most frequently activated. In the case of power transformers, overload protection and, in some cases, differential or Buchholz protection schemes were triggered.

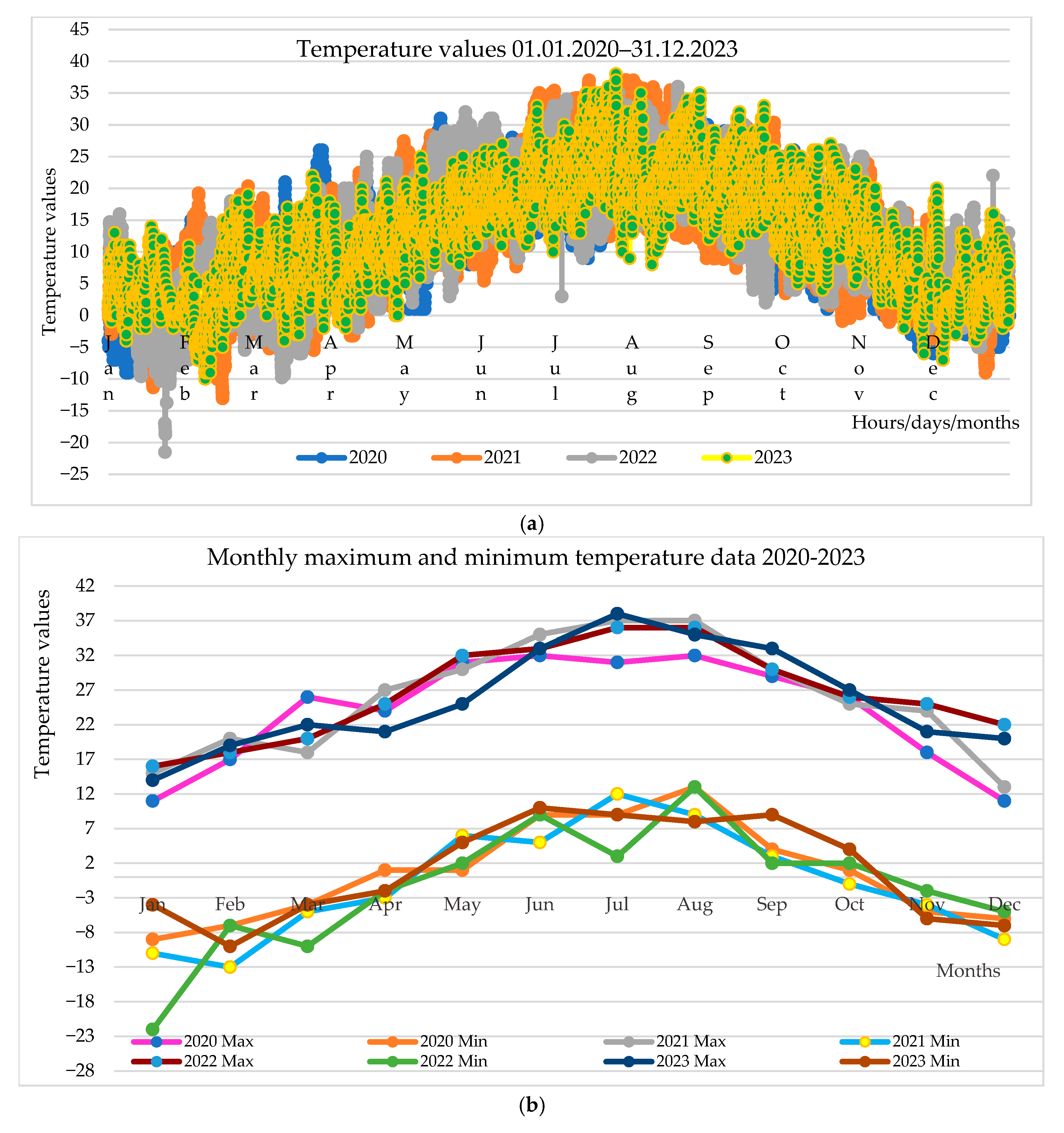

Figure 5 presents the meteorological temperature data recorded during the period of 1 January 2020 to 31 December 2023, including hourly temperature values and the corresponding monthly maximum and minimum temperatures.

The recorded data indicate that the highest annual temperatures were 32 °C in 2020, 37 °C in 2021, 36 °C in 2022, and 38 °C in 2023, while the lowest temperatures were −9 °C, −13 °C, −22 °C, and −10 °C, respectively.

Temperature and weather conditions have a direct influence on the failure frequency of overhead transmission lines and power transformers. Although the present study primarily focuses on structural and operational parameters, the observed temperature profiles suggest a potential correlation between extreme temperature events and increased outage rates. Future research will incorporate statistical regression techniques to quantify this relationship and to evaluate whether meteorological variables can be integrated as probabilistic modifiers of component reliability.

3.3. Methodological Approach

The proposed methodological framework consists of a sequence of structured steps, combining conventional power system modeling with complex network analysis. The methodology applied in this study can be summarized as follows:

Step 1: Data collection.

Multiple datasets related to substations, transmission lines, and power transformers were collected and stored in a database. The datasets included meteorological data (temperature in °C) and records of all faults occurring within the western part of the transmission system.

Step 2: Model creation using Neplan and NetworkX.

A detailed power grid model was developed using the Neplan engineering software. In parallel, the Python NetworkX library was used to create and model a corresponding graph representation of the transmission system.

Step 3: Simulation and metric computation.

Power system simulations were performed using Neplan, while graph-theoretic metrics were calculated using Python NetworkX.

Step 4: Result extraction.

Simulation outputs from Neplan and topological metrics from NetworkX were extracted for further analysis.

Step 5: Result validation and integration.

The results obtained from both approaches were validated and combined to ensure consistency between functional (power flow) and structural (network topology) analyses.

Step 6: Iteration and termination.

If the obtained results satisfied the validation criteria, the analysis cycle was terminated; otherwise, the process was repeated.

The complete workflow of the proposed methodology is illustrated in

Figure 6.

Data exchange between Neplan and Python was automated using a CSV-based export–import routine. Neplan data files containing node, branch, and impedance parameters were parsed using a custom Python script that generated NetworkX graph objects directly. This procedure ensured consistency in network topology and attribute values across both environments without requiring manual intervention.

Validation of the data exchange process was performed by comparing node–branch connectivity matrices and impedance parameters between the Neplan and NetworkX datasets. The number of nodes, transmission lines, and connectivity relationships was identical in both representations, while differences in impedance values remained below ±1%. As shown in the workflow diagram, the proposed approach integrates Neplan-based engineering simulations with complex network analysis using Python NetworkX.

Power flow analysis represents a conventional technique for computing voltages, currents, and power flows under specific operating conditions, focusing on the steady-state behavior of the grid. It provides a detailed representation of the system’s operational state, including power flows on transmission lines and voltage magnitudes and phase angles at each bus. Power flow analysis involves solving a set of nonlinear equations that describe the power balance at each network bus.

In contrast, complex network analysis focuses on the topological and structural properties of the transmission grid, providing insights into system resilience, vulnerability, and overall behavior. By representing the grid as a graph with buses as nodes and transmission lines as edges, this methodology evaluates network structure using graph-theoretic concepts such as path lengths, clustering coefficients, and centrality measures (degree, betweenness, and closeness). This analysis enables the identification of critical nodes, structural weaknesses, and potential cascading failure paths, thereby complementing conventional engineering analyses.

It should be noted that the present study focuses on steady-state operating conditions. Transient stability and frequency deviation analyses were intentionally excluded, as they require time-domain dynamic modeling and different data structures. These aspects will be addressed in future work to extend the proposed hybrid framework toward dynamic and cascading failure analyses.

3.4. System Under Study

Figure 7 illustrates the system under study and its corresponding undirected graph representation. The system consists of a 14-bus transmission network, including substations, transmission lines, generators, and load points, and forms an integral part of the Kosovo power transmission system. The aggregated demand of the analyzed network segment is 310 MW and 41 MVar.

Data related to substations, transmission lines, power transformers, generators, and loads were collected in order to perform power flow analyses and calculate network centrality metrics.

Neplan was employed as the primary simulation tool to analyze the steady-state performance of the power transmission system under various operating conditions.

NetworkX, a Python library (version 3.13.1) for the construction, modification, and analysis of complex networks, was used to compute centrality measures and other graph-theoretic metrics. These metrics provide quantitative indicators of node importance within the network.

Although the analyzed case corresponds to the western regional segment of the Kosovo transmission network, its topology—including multiple voltage levels, interconnected substations, and mixed generation sources—is representative of many medium-scale European transmission systems. Consequently, the proposed methodology is scalable and can be extended to larger national or cross-border transmission networks by adjusting the input data and network size.

4. Obtained Results and Discussion

4.1. Power Flow Analyses

Load flow analysis is a fundamental numerical technique used to evaluate the steady-state operating conditions of electrical power systems. It enables the estimation of voltage magnitudes, currents, and active and reactive power flows under specified operating scenarios. This analysis is essential for power system planning, design, and operation, as it allows engineers to verify that voltages and currents remain within acceptable limits, assess the impact of system modifications, identify potential operational bottlenecks, and optimize energy utilization.

Power flow analysis involves solving a set of nonlinear algebraic equations that describe the power balance at each bus of the network. These equations are typically solved using iterative numerical methods, such as the Newton–Raphson or Gauss–Seidel techniques. In this study, the Neplan software was employed to perform advanced power system analyses, including steady-state power flow simulations and network security assessments. Neplan also supports the integration of renewable energy sources and provides functionality for reliability and security studies [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36].

Two operating scenarios were simulated for the transmission system under study. In the first scenario, power flow and network security analyses were conducted under the assumption that the transmission line between electrical substations SS2 and SS9 was unavailable due to scheduled maintenance. In the second scenario, an additional contingency was introduced by assuming a fault-induced outage of the transmission line between substations SS1 and SS3, while the line between SS2 and SS9 remained under maintenance.

Power flow and network security analyses for both scenarios were carried out using the Newton–Raphson method implemented in Neplan. The corresponding simulation results are presented in

Figure 8 and summarized in

Table 3 for the first and second scenarios, respectively.

Table 3 reports the active (P) and reactive (Q) power flows for selected monitored transmission lines under both scenarios. As illustrated in

Figure 8, the system response differs notably between the two operating conditions. In particular, the transmission line connecting SS5 and SS6 exhibits a significant increase in power flow in the second scenario, indicating higher loading under contingency conditions. Similarly, changes in power flow direction and magnitude are observed for the line between SS3 and SS8.

The analysis indicates that substation SS8 becomes increasingly critical under contingency conditions, as reflected by both the redistribution of power flows and the increased loading of adjacent transmission lines. The line connecting SS5 and SS6 also emerges as a key element influencing system performance under stressed operating conditions.

4.2. Calculation and Analysis of Graph Components

Power transmission systems, comprising generators, transmission lines, substations, and loads, can be effectively represented as networks with nodes corresponding to system components and edges representing physical connections. Complex network analysis provides valuable insights into the structural properties of such systems, enabling the identification of vulnerabilities, critical nodes, and potential failure propagation paths. Graph-based representations are therefore widely used in power system studies to analyze connectivity, assess vulnerability to failures, and support operational optimization [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43].

A set of relevant studies was reviewed to support the application of complex network theory in the present work [

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52].

The degree of a node in a network is defined as the number of edges connected to that node. For the analyzed transmission system, the degree values of electrical substations (SSs) in the corresponding graph representation are reported in

Table 4.

As shown in

Table 4, substations SS1 and SS8 exhibit the highest node degrees, indicating a larger number of direct connections compared to other substations. Such nodes typically play an important role in maintaining network connectivity.

Python NetworkX was used to compute the degree, degree centrality, closeness centrality, betweenness centrality, and eigenvector centrality of each node in the network. The calculated values for both operating scenarios are presented in

Table 5.

Degree centrality values range between 0 and 1, with higher values indicating nodes that are more central within the network. The removal of nodes with high degree centrality can significantly affect overall connectivity, as these nodes are typically well connected to other network elements. In the analyzed system, substations SS8 and SS7 exhibit the highest degree centrality values in both scenarios.

Closeness centrality quantifies how close a node is to all other nodes in the network on average. Higher values indicate shorter average distances to other nodes. In the first scenario, substations SS8 and SS9 show the highest closeness centrality values, while in the second scenario, SS8 and SS7 become the most central nodes according to this metric.

Betweenness centrality measures the extent to which a node lies on the shortest paths between other node pairs. Nodes with high betweenness centrality values often act as bridges within the network, and their failure may lead to significant connectivity disruptions. In the present case study, substations SS8 and SS9 exhibit the highest betweenness centrality values in the first scenario, whereas SS8 and SS7 dominate in the second scenario.

Eigenvector centrality reflects not only the importance of a node but also the importance of its neighboring nodes. Higher eigenvector centrality values indicate nodes that are connected to other influential nodes within the network. For the analyzed system, the highest eigenvector centrality values are associated with substations SS8 and SS9 in the first scenario and with SS8 and SS7 in the second scenario.

The combined analysis of centrality metrics reveals a consistent pattern across both operating scenarios. Substation SS8 emerges as the most critical node from a topological perspective, as it exhibits high values across multiple centrality measures. This finding aligns with the results obtained from the power flow simulations, where SS8 also plays a significant role in redistributing power flows under contingency conditions.

Figure 9 presents a graphical comparison of degree centrality, closeness centrality, betweenness centrality, and eigenvector centrality for both simulated scenarios. This visual comparison highlights the shifts in node importance resulting from changes in network topology and operating conditions.

Dot plots and box plots were also employed to visualize the distribution of centrality metrics across the network. Dot plots illustrate the frequency and dispersion of individual data points, facilitating the identification of central tendencies and outliers. Box plots provide a compact representation of data distribution, highlighting median values, interquartile ranges, and potential outliers.

Figure 10 shows the dot plots and box plots for both scenarios. The dot plots depict the distribution of degree centrality (red), closeness centrality (green), betweenness centrality (blue), and eigenvector centrality (purple) values for Scenario 1 and Scenario 2. The box plots summarize the corresponding distributions and enable direct comparison between the two operating conditions.

The correlation coefficient R

2, also known as the coefficient of determination, represents the proportion of variance in a dependent variable that can be explained by an independent variable. Values of R

2 range from 0, indicating no correlation, to 1, indicating a perfect fit. The coefficient can be calculated using the following expression:

where SSR is the Sum of Squares of Residuals (or Sum of Squares Error), and SST is the Total Sum of Squares. These two parameters can be calculated as follows:

where y

i is the observed value;

is the predicted value; and y is a dependent variable that is predictable based on the independent variable x.

Table 6 summarizes the relationship between substations exhibiting high centrality values and those experiencing significant power flow variations or voltage deviations under both simulated scenarios. The obtained correlation coefficient (R

2 = 0.76) indicates a strong alignment between topological criticality and operational stress points, confirming the complementary nature of the two analytical approaches.

As shown in

Table 6, substations SS8 and SS7 exhibit both high centrality metrics and significant variations in active power flow and voltage magnitude. This result demonstrates that the proposed hybrid approach effectively identifies functionally critical nodes within the transmission system by combining structural and operational analyses.

5. Conclusions

Maintaining reliability and security in modern power transmission systems has become increasingly challenging as these systems incorporate a growing number of innovative and interconnected components, including smart devices, electric vehicles, renewable energy sources, and battery storage systems. To ensure reliable grid operation and to enhance the realism of analytical models, continuous network security and reliability assessments are required.

The primary objective of this study was to address the challenges associated with modern power systems by evaluating the reliability and security of a power transmission system through a hybrid approach that combines conventional engineering analysis using the Neplan software with complex network analysis implemented in Python NetworkX. The proposed methodology was applied to a transmission system consisting of 14 substations. Power flow analyses were conducted using Neplan to investigate system behavior under two operating scenarios: a transmission line outage due to maintenance and a contingency involving the loss of an additional transmission line while the first remained unavailable.

In parallel, complex network analysis was employed to identify structurally important nodes and connections within the transmission network using topological metrics such as degree centrality, closeness centrality, and betweenness centrality. By combining these structural indicators with the functional power flow results, the proposed approach enabled the rapid identification of potentially critical substations and transmission elements. Detailed engineering simulations were then used to further analyze the operational implications of these critical components.

The results demonstrate that integrating complex network concepts with conventional power system analysis enhances the assessment of transmission system reliability and security. This hybrid framework provides improved insight into system control and operation, supports more informed decision-making, and facilitates the optimized planning of transmission infrastructure, particularly in the context of increasing renewable energy penetration and growing demand.

This study presents a comprehensive evaluation of power transmission system reliability and security under the conditions of transmission line failures. As transmission networks continue to evolve, failure scenarios involving transmission lines and power transformers are expected to become more complex. Consequently, further research is required to extend the proposed methodology to larger-scale transmission systems at regional or national levels. Future work will also focus on incorporating dynamic analyses, such as transient stability and cascading failure modeling, to further enhance the applicability of the proposed hybrid framework.