Improving Satisfaction with Assistive Technology Through Better Service Delivery: Evidence from the WHO rATA Survey in Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

Aim of the Study

RQ1: What is the impact of pre-delivery and post-delivery assistive technology services on user satisfaction with assistive products?

RQ2: To what extent is the relationship between product satisfaction and product use mediated by satisfaction with assistive technology service delivery process?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Context, Design, and Data Source

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Explorative Analyses

3.2. RQ1: What Is the Impact of Pre-Delivery and Post-Delivery Assistive Technology Services on User Satisfaction with Assistive Products?

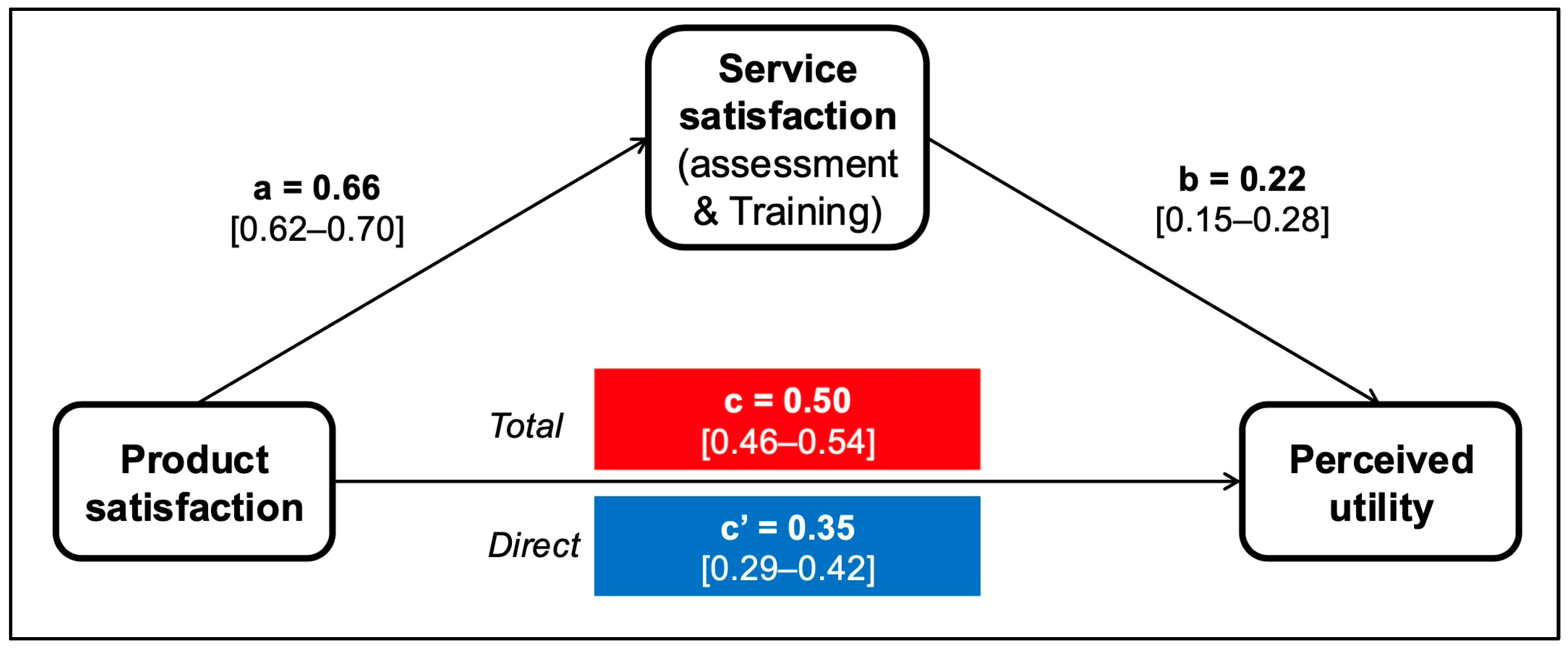

3.3. RQ2: To What Extent Is the Relationship Between Product Satisfaction and Product Use Mediated by Satisfaction with Assistive Technology Service Delivery Process?

4. Discussion

4.1. The Comparative Impact of Pre- and Post-Delivery Services (RQ1)

4.2. Mediation of Service Satisfaction in Product Use (RQ2)

4.3. Practical Implications

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Product Satisfaction | Service Satisfaction (Pre-Delivery) | Service Satisfaction (Post-Delivery) | Age | Sum of Difficulties | Sum of Products | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product satisfaction | Pearson’s r | ||||||

| df | |||||||

| p-value | |||||||

| Service satisfaction (pre-delivery) | Pearson’s r | 0.731 *** | |||||

| df | 990 | ||||||

| p-value | <0.001 | ||||||

| Service satisfaction (post-delivery) | Pearson’s r | 0.660 *** | 0.670 *** | ||||

| df | 990 | 990 | |||||

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| Age | Pearson’s r | 0.184 *** | 0.153 *** | 0.186 *** | |||

| df | 990 | 990 | 990 | ||||

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Sum of difficulties | Pearson’s r | −0.104 *** | −0.084 ** | −0.102 ** | 0.270 *** | ||

| df | 990 | 990 | 990 | 990 | |||

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.008 | 0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Sum of products | Pearson’s r | −0.120 *** | −0.070 * | −0.093 ** | −0.127 *** | 0.299 *** | |

| df | 990 | 990 | 990 | 990 | 990 | ||

| p-value | <0.001 | 0.028 | 0.003 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Appendix B

| 95% C.I. (a) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Effect | Estimate | SE | Lower | Upper | β | z | p |

| Indirect | Product satisfaction ⇒ Service satisfaction (pre-delivery) ⇒ Perceived utility | 0.146 | 0.023 | 0.100 | 0.193 | 0.167 | 6.154 | <0.001 |

| Proxy respondent ⇒ Service satisfaction (pre-delivery) ⇒ Perceived utility | −0.014 | 0.011 | −0.037 | 0.008 | −0.009 | −1.245 | 0.213 | |

| Age (0–17) ⇒ Service satisfaction (pre-delivery) ⇒ Perceived utility | −0.004 | 0.014 | −0.033 | 0.024 | −0.002 | −0.279 | 0.781 | |

| Age (18–59) ⇒ Service satisfaction (pre-delivery) ⇒ Perceived utility | 0.013 | 0.013 | −0.012 | 0.039 | 0.008 | 1.026 | 0.305 | |

| Sex (Male) ⇒ Service satisfaction (pre-delivery) ⇒ Perceived utility | −0.019 | 0.008 | −0.036 | −0.003 | −0.012 | −2.326 | 0.020 | |

| Component | Product satisfaction ⇒ Service satisfaction (pre-delivery) | 0.666 | 0.020 | 0.626 | 0.705 | 0.727 | 33.300 | <0.001 |

| Service satisfaction (pre-delivery) ⇒ Perceived utility | 0.220 | 0.03 | 0.151 | 0.289 | 0.229 | 6.262 | <0.001 | |

| Proxy respondent ⇒ Service satisfaction (pre-delivery) | −0.065 | 0.051 | −0.166 | 0.035 | −0.039 | −1.270 | 0.204 | |

| Age (0–17) ⇒ Service satisfaction (pre-delivery) | −0.018 | 0.067 | −0.150 | 0.113 | −0.011 | −0.279 | 0.780 | |

| Age (18–59) ⇒ Service satisfaction (pre-delivery) | 0.061 | 0.058 | −0.054 | 0.176 | 0.035 | 1.041 | 0.298 | |

| Sex (Male) ⇒ Service satisfaction (pre-delivery) | −0.089 | 0.035 | −0.159 | −0.019 | −0.055 | −2.505 | 0.012 | |

| Direct | Product satisfaction ⇒ Perceived utility | 0.357 | 0.032 | 0.294 | 0.420 | 0.407 | 11.091 | <0.001 |

| Proxy respondent ⇒ Perceived utility | −0.146 | 0.057 | −0.258 | −0.034 | −0.091 | −2.573 | 0.010 | |

| Age (0–17) ⇒ Perceived utility | −0.089 | 0.074 | −0.235 | 0.056 | −0.057 | −1.198 | 0.231 | |

| Age (18–59) ⇒ Perceived utility | 0.042 | 0.065 | −0.085 | 0.169 | 0.025 | 0.649 | 0.517 | |

| Sex (Male) ⇒ Perceived utility | 0.050 | 0.039 | −0.027 | 0.128 | 0.032 | 1.281 | 0.200 | |

| Total | Product satisfaction ⇒ Perceived utility | 0.504 | 0.022 | 0.460 | 0.548 | 0.575 | 22.313 | <0.001 |

| Proxy respondent ⇒ Perceived utility | −0.161 | 0.058 | −0.275 | −0.047 | −0.100 | −2.771 | 0.006 | |

| Age (0–17) ⇒ Perceived utility | −0.093 | 0.076 | −0.242 | 0.055 | −0.060 | −1.229 | 0.219 | |

| Age (18–59) ⇒ Perceived utility | 0.055 | 0.066 | −0.07 | 0.185 | 0.033 | 0.839 | 0.401 | |

| Sex (Male) ⇒ Perceived utility | 0.031 | 0.040 | −0.048 | 0.110 | 0.020 | 0.771 | 0.440 | |

References

- Bauer, S.; Elsaesser, L.J.; Scherer, M.; Sax, C.; Arthanat, S. Promoting a standard for assistive technology service delivery. Technol. Disabil. 2014, 26, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Witte, L.; Knops, H.; Pyfers, L.; Roben, P.; Johnson, I.; Andrich, R. European Service Delivery Systems in Rehabilitation Technology; European Commission: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- de Witte, L.; Steel, E.; Gupta, S.; Ramos, V.D.; Roentgen, U. Assistive technology provision: Towards an international framework for assuring availability and accessibility of affordable high-quality assistive technology. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2018, 13, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layton, N.; Spann, A.; Khan, M.; Contepomi, S.; Hoogerwerf, E.J.; de Witte, L. Scoping Review of Quality Guidelines for Assistive Technology Provision; Global Alliance of Assistive Technology Organizations (GAATO): London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://at2030.org/static/at2030_core/outputs/GAATO_Service_Provision_added_content_re_2023_Guideline.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Association for the Advancement of Assistive Technology in Europe (AAATE). Service Delivery Systems for Assistive Technology in Europe—Position Paper; AAATE: Enschede, The Netherlands, 2012; Available online: https://aaate.net/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2016/02/ATServiceDelivery_PositionPaper.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Smith, R.O. Measuring the outcomes of assistive technology: Challenge and innovation. Assist. Technol. 1996, 8, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrer, M.J.; Jutai, J.W.; Scherer, M.J.; DeRuyter, F. A framework for the conceptual modelling of assistive technology device outcomes. Disabil. Rehabil. 2003, 25, 1243–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desideri, L.; Salatino, C.; Borgnis, F. Assistive technology service delivery outcome assessment: From challenges to standards. In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Disability; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joskow, R.; Patel, D.; Landre, A.; Mattick, K.; Holloway, C.; Danemayer, J.; Austin, V. Understanding the impact of assistive technology on users’ lives in England: A capability approach. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layton, N.; Smith, R.O.; Smith, E.M. Global outcomes of assistive technology: What we measure, we can improve. Assist. Technol. 2022, 34, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, M.J. Technology adoption, acceptance, satisfaction and benefit: Integrating various assistive technology outcomes. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2017, 12, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherer, M.J.; Smith, R.O.; Layton, N.; Scherer, M.J. Committing to assistive technology outcomes and synthesizing practice, research and policy. Glob. Perspect. Assist. Technol. 2019, 2, 196–203. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO); United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Global Report on Assistive Technology; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240049451 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Petrie, H.; Carmien, S.; Lewis, A. Assistive technology abandonment: Research realities and potentials. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Computers Helping People with Special Needs (ICCHP 2018), Linz, Austria, 11–13 July 2018; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, B.; Zhao, H. Predictors of assistive technology abandonment. Assist. Technol. 1993, 5, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Layton, N.; Callaway, L.; Wilson, E.; Bell, D.; Prain, M.; Noonan, M.; Doyle, E. My assistive technology outcomes framework: Rights-based outcome tools for consumers to “measure what matters”. Assist. Technol. 2025, 37, S27–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Ruyter, F. Evaluating outcomes in assistive technology: Do we understand the commitment? Assist. Technol. 1995, 7, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ruyter, F. The importance of outcome measures for assistive technology service delivery systems. Technol. Disabil. 1997, 6, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Alliance of Assistive Technology Organisations (GAATO). GAATO AT Outcomes Grand Challenge Consultation; GAATO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.gaato.org/grand-challenges (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Priority Research Agenda for Improving Access to High-Quality Affordable Assistive Technology; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Seventy-First World Health Assembly. Resolutions and Decisions Annexes; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA71-REC1/A71_2018_REC1-en.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Access to Assistive Technology: The Global Situation and Role of Pharmacy; Presentation at WHO Technical Briefing Seminar on Medicines and Health Products, Geneva, Switzerland, 10 May 2023. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/health-products-policy-and-standards/18_access-to-assistive-technology-the-global-situation-and-role-of-pharmacy---kylie-shae---irene-calvo.pdf?sfvrsn=a531888b_1 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Weiss-Lambrou, R. Satisfaction and comfort. In Assistive Technology: Matching Device and Consumer for Successful Rehabilitation; Scherer, M.J., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Borgnis, F.; Desideri, L.; Converti, R.M.; Salatino, C. Available assistive technology outcome measures: Systematic review. JMIR Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2023, 10, e51124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranada, Å.L.; Lidström, H. Satisfaction with assistive technology device in relation to the service delivery process—A systematic review. Assist. Technol. 2019, 31, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, K.L.; Smith, R.O. Satisfaction with assistive technology: What are we measuring? In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Technology & Disability: Research, Design, Practice & Policy (RESNA 2004), Orlando, FL, USA, 18–22 June 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Steel, E.J.; Layton, N.A.; Foster, M.M.; Bennett, S. Challenges of user-centred assistive technology provision in Australia: Shopping without a prescription. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2016, 11, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandt, Å.; Hansen, E.M.; Christensen, J.R. The effects of assistive technology service delivery processes and factors associated with positive outcomes—A systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2020, 15, 590–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, J.; Larsson, S.; Östergren, P.O.; Rahman, A.A.; Bari, N.; Khan, A.N. User involvement in service delivery predicts outcomes of assistive technology use: A cross-sectional study in Bangladesh. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.K.; Martin, L.G.; Stumbo, N.J.; Morrill, J.H. The impact of consumer involvement on satisfaction with and use of assistive technology. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2011, 6, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, J.; Rushton, S.; Bhattarai, S.; Norman, G.; Rakhshanda, S.; De Witte, P.L. Processes of assistive technology service delivery in Bangladesh, India and Nepal: A critical reflection. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2024, 19, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federici, S.; Scherer, M.; Borsci, S. An ideal model of an assistive technology assessment and delivery process. Technol. Disabil. 2014, 26, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, D.M.; Turner-Smith, A.R. The user’s perspective on the provision of electronic assistive technology: Equipped for life? Br. J. Occup. Ther. 1999, 62, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, L.A.; Boninger, M.L.; Oyster, M.L.; Williams, S.; Houlihan, B.; Lieberman, J.A.; Cooper, R.A. Wheelchair repairs, breakdown, and adverse consequences for people with traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2009, 90, 2034–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Wang, B.; Hu, Z.; Qin, X.; Wang, H.; Hu, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, Y. The demand for assistive technology, services, and satisfaction self-reports among people with disabilities in China. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2025, 20, 1199–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desideri, L.; Magni, R.; Guerreschi, M.; Bitelli, C.; Hoogerwerf, E.J.; Vaccaro, C.; Giansanti, D. Need and access to assistive technology in Italy: Results from the rATA survey. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2025, 20, 2327–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Eide, A.H.; Pryor, W.; Khasnabis, C.; Borg, J. Measuring self-reported access to assistive technology using the WHO rapid assistive technology assessment (rATA) questionnaire: Protocol for a multi-country study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherer, M.J.; Craddock, G. Matching person & technology (MPT) assessment process. Technol. Disabil. 2002, 14, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senjam, S.S.; Manna, S.; Titiyal, J.S.; Kumar, A.; Kishore, J. User satisfaction and dissatisfaction with assistive technology devices and services in India. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apeagyei, A.E.; Bisignano, C.; Elliott, H.; Hay, S.I.; Lidral-Porter, B.; Nam, S.; Dieleman, J.L. Tracking development assistance for health, 1990–2030: Historical trends, recent cuts, and outlook. Lancet 2025, 406, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, J.; Winberg, M.; Eide, A.H.; Calvo, I.; Khasnabis, C.; Zhang, W. On the relation between assistive technology system elements and access to assistive products based on 20 country surveys. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Males | 502 (50.6%) |

| Females | 490 (49.4%) | |

| Age | 0–17 | 188 (19.0%) |

| 18–59 | 482 (48.6%) | |

| 60+ | 322 (32.5%) | |

| Functional difficulties | None | 92 (9.3%) |

| Some | 392 (39.8%) | |

| Severe | 360 (36.6%) | |

| Complete | 140 (14.2%) | |

| Domain of AT use | Mobility | 70 (7.1%) |

| Seeing | 76 (7.7%) | |

| Hearing | 16 (1.6%) | |

| Communication | 3 (0.3%) | |

| Cognition | 18 (1.8%) | |

| Self-care | 6 (0.6%) | |

| Mixed | 803 (80.9%) |

| Dimension | Question Text | Response Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Product satisfaction | Over the last month, how satisfied are you with your [PROD#]? | 1 = Very dissatisfied; 5 = Very satisfied |

| Service satisfaction (Pre-delivery) | Thinking about your [PROD#], how satisfied are you with the assessment and training you received? | 1 = Very dissatisfied; 5 = Very satisfied |

| Service satisfaction (Post-delivery) | Please think about your [PROD#]. How satisfied are you with the repair, maintenance and follow-up services based on your last experience? | 1 = Very dissatisfied; 5 = Very satisfied |

| Perceived utility | To what extent does your [PROD#] help you to do what you want? | 1 = Not at all; 5 = Completely |

| Predictor | Estimate (β) | SE | t | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.002 | 0.001 | 2.040 | 0.042 |

| Sex (Female vs. Male) | 0.090 | 0.037 | 2.444 | 0.015 |

| Number of Products | −0.012 | 0.006 | −1.901 | 0.058 |

| Proxy vs. Self-report | 0.030 | 0.039 | 0.761 | 0.447 |

| Functional Difficulty | −0.011 | 0.007 | −1.655 | 0.098 |

| Pre-delivery Satisfaction | 0.571 | 0.030 | 19.074 | <0.001 |

| Post-delivery Satisfaction | 0.280 | 0.027 | 10.537 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Desideri, L.; Magni, R.; Zanfardino, F.; Hoogerwerf, E.-J.; Vaccaro, C.; Gregori Grgič, R.; De Santis, M.; Romeo, R.I.; Capuano, E.I.; Morelli, S.; et al. Improving Satisfaction with Assistive Technology Through Better Service Delivery: Evidence from the WHO rATA Survey in Italy. Technologies 2026, 14, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14010010

Desideri L, Magni R, Zanfardino F, Hoogerwerf E-J, Vaccaro C, Gregori Grgič R, De Santis M, Romeo RI, Capuano EI, Morelli S, et al. Improving Satisfaction with Assistive Technology Through Better Service Delivery: Evidence from the WHO rATA Survey in Italy. Technologies. 2026; 14(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleDesideri, Lorenzo, Riccardo Magni, Francesco Zanfardino, Evert-Jan Hoogerwerf, Concetta Vaccaro, Regina Gregori Grgič, Marta De Santis, Rosa Immacolata Romeo, Elena Ilaria Capuano, Sandra Morelli, and et al. 2026. "Improving Satisfaction with Assistive Technology Through Better Service Delivery: Evidence from the WHO rATA Survey in Italy" Technologies 14, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14010010

APA StyleDesideri, L., Magni, R., Zanfardino, F., Hoogerwerf, E.-J., Vaccaro, C., Gregori Grgič, R., De Santis, M., Romeo, R. I., Capuano, E. I., Morelli, S., Pirrera, A., & Giansanti, D. (2026). Improving Satisfaction with Assistive Technology Through Better Service Delivery: Evidence from the WHO rATA Survey in Italy. Technologies, 14(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies14010010